Ancient maritime history

Encyclopedia

Maritime history

dates back thousands of years. In ancient maritime history, the first boats are presumed to have been dugout canoes

which were developed independently by various stone age populations. In ancient history

, various vessels were used for coastal fishing and travel.

The Indigenous of the Pacific Northwest

The Indigenous of the Pacific Northwest

are very skilled at crafting wood. Best known for totem poles up to 80 feet (24 m) tall, they also construct dugout canoes over 60 feet (18.3 m) long for everyday use and ceremonial purposes.

The earliest seaworthy boats may have been developed as early as 45,000 years ago, according to one hypothesis explaining the habitation of Australia

. In the history of whaling

, humans began whaling in pre-historic times. The oldest known method of catching whales is to simply drive them ashore by placing a number of small boats between the whale and the open sea and attempting to frighten them with noise, activity, and perhaps small, non-lethal weapons such as arrows. Typically, this was used for small species, such as Pilot Whales, Belugas and Narwhals.

The earliest known reference to an organization devoted to ships in ancient India

is to the Mauryan Empire from the 4th century BC. It is believed that the navigation as a science originated on the river Indus some 5000 years ago.

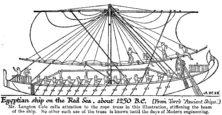

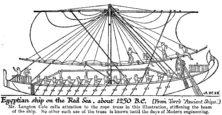

The Ancient Egypt

The Ancient Egypt

ians had knowledge to some extent of sail

construction. This is governed by the science of aerodynamics

. A primary feature of a properly designed sail is an amount of "draft

", caused by curvature of the surface of the sail. According to the Greek

historian Herodotus

, Necho II sent out an expedition of Phoenicians, which in three years sailed from the Red Sea

around Africa

to the mouth of the Nile

. Many current historians tend to believe Herodotus on this point, even though he himself was in disbelief that the Phoenicians had accomplished the act, arguing that his doubts mainly originated in the news the sailors had seen the Sun in the north and that he would definitely have counted so fantastic an assertion a typical example of some seafarers' cock-and-bull story and therefore never have mentioned it, at all, had it not been based on facts and made with the according insistence. The Egyptologist Alan Lloyd suggests that the Greeks at this time understood that anyone going south far enough and then turning west would have the Sun on their right but found it unbelievable that Africa reached so far south. He suggests that "It is extremely unlikely that an Egyptian king would, or could, have acted as Necho is depicted as doing" and that the story might have been triggered by the failure of Sataspes' attempt to circumnavigate Africa under Xerxes the Great.

Hannu

was an ancient Egyptian explorer

(around 2750 BC) and the first explorer of whom there is any knowledge. He made the first recorded exploring expedition and wrote his account of the exploration in stone. He traveled along the Red Sea

to Punt and sailed to what is now part of eastern Ethiopia

and Somalia

. He returned to Egypt with great treasures, including precious myrrh

, metal and wood.

The Sea Peoples

was a confederacy

of seafaring raiders who sailed into the eastern shores of the Mediterranean, caused political unrest, and attempted to enter or control Egypt

ian territory during the late 19th dynasty

, and especially during Year 8 of Ramesses III of the 20th Dynasty

. The Egyptian Pharaoh Merneptah

explicitly refers to them by the term "the foreign-countries (or 'peoples') of the sea" in his Great Karnak Inscription

. Although some scholars believe that they "invaded" Cyprus

, Hati

and the Levant

, this hypothesis is disputed.

, which is believed by several Egyptologists to have been situated in the area of modern-day Somalia

, had a steady trade link with the Ancient Egyptians and exported the precious natural resources such as myrrh

, frankincense

and gum

. This trade network continued all the way into the classical era

. The city states of Mossylon, Opone, Malao, Mundus

and Tabae

in Somalia engaged in a lucrative trade network connecting Somali

merchants with Phoenicia

, Ptolemic Egypt

, Greece

, Parthian Persia

, Saba

, Nabataea and the Roman Empire

. Somali sailors used the ancient Somali maritime vessel known as the beden

to transport their cargo.

traders from Crete

were active in the eastern Mediterranean by the 2nd millennium BC. The Phoenicia

ns were an ancient civilization

centered in the north of ancient Canaan

, with its heartland along the coast of modern day Lebanon

, Syria

and northern Israel

. Phoenician civilization was an enterprising maritime trading culture

that spread across the Mediterranean during the first millennium BC, between the period of 1200 BC to 900 BC. Though ancient boundaries of such city-centered cultures fluctuated, the city of Tyre seems to have been the southernmost. Sarepta

between Sidon

and Tyre, is the most thoroughly excavated city of the Phoenician homeland. The Phoenicians often traded by means of a galley, a man-powered sailing vessel. They were the first civilization to create the bireme. There is still debate on the subject of whether the Canaanites and Phoenicians were different peoples or not.

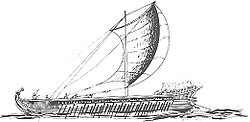

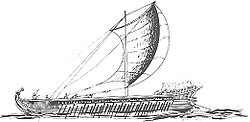

The Mediterranean was the source of the vessel, galley, developed before 1000 BC, and development of nautical technology supported the expansion of Mediterranean culture. The Greek

trireme

was the most common ship of the ancient Mediterranean world, employing the propulsion power of oar

smen. Mediterranean peoples developed lighthouse

technology and built large fire-based lighthouses, most notably the Lighthouse of Alexandria

, built in the 3rd century BC (between 285 and 247 BC) on the island of Pharos in Alexandria, Egypt.

Many in ancient western societies, such as Ancient Greece

, were in awe of the seas and deified them, believing that man no longer belonged to himself when once he embarked on a sea voyage. They believed that he was liable to be sacrificed at any time to the anger of the great Sea God

. Before the Greeks, the Carians

were an early Mediterranean seagoing people that travelled far. Early writers do not give a good idea about the progress of navigation nor that of the man's seamanship. One of the early stories of seafaring was that of Odysseus

.

In Greek mythology

, the Argonauts

were a band of heroes who, in the years before the Trojan War

, accompanied Jason

to Colchis

in his quest to find the Golden Fleece

. Their name comes from their ship, the Argo

which in turn was named after its builder Argus

. Thus, "Argonauts" literally means "Argo sailors". The voyage of the Greek navigator Pytheas of Massalia

is an example of a very early voyage. A competent astronomer and geographer, Pytheas ventured from Greece to Western Europe and the British Isles.

The periplus

, literally "a sailing-around', in the ancient navigation of Phoenicians, Greeks

, and Romans

was a manuscript document that listed in order the ports and coastal landmarks, with approximate distances between, that the captain of a vessel could expect to find along a shore. Several examples of periploi have survived.

The concept of an underwater boat

has roots deep in antiquity. The very first report of someone attempting to put the idea into practice seems to have been an attempt by Alexander the Great. According to Aristotle

, Alexander the Great had developed a primitive submersible

for reconnaissance missions by 332BC.

Piracy

, which is a robbery

committed at sea or sometimes on the shore, dates back to Classical Antiquity

and, in all likelihood, much further. The Tyrrhenians

, Illyrians

and Thracians

were known as pirates in ancient times. The island of Lemnos

long resisted Greek

influence and remained a haven for Thracian pirates. By the 1st century BC, there were pirate states along the Anatolia

n coast, threatening the commerce

of the Roman Empire

.

In Ionia

In Ionia

(the modern Aegean coast of Turkey

) the Greek cities, which included great centres such as Miletus

and Halicarnassus

, were unable to maintain their independence and came under the rule of the Persian Empire in the mid 6th century BC. In 499 BC the Greeks

rose in the Ionian Revolt

, and Athens

and some other Greek cities went to their aid. In 490 BC the Persian Great King, Darius I

, having suppressed the Ionian cities, sent a fleet to punish the Greeks. The Persians landed in Attica

, but were defeated at the Battle of Marathon

by a Greek army led by the Athenian general Miltiades

. The burial mound of the Athenian dead can still be seen at Marathon. Ten years later Darius' successor, Xerxes I

, sent a much more powerful force by land. After being delayed by the Spartan King Leonidas I at Thermopylae

, Xerxes advanced into Attica, where he captured and burned Athens. But the Athenians had evacuated the city by sea, and under Themistocles

they defeated the Persian fleet at the Battle of Salamis

. A year later, the Greeks, under the Spartan Pausanius

, defeated the Persian army at Plataea

. The Athenian fleet then turned to chasing the Persians out of the Aegean Sea, and in 478 BC they captured Byzantium

. In the course of doing so Athens enrolled all the island states and some mainland allies into an alliance, called the Delian League

because its treasury was kept on the sacred island of Delos

. The Sparta

ns, although they had taken part in the war, withdrew into isolation after it, allowing Athens to establish unchallenged naval and commercial

power.

The Achaean League

The Achaean League

was a confederation

of Greek

city state

s in Achaea

, a territory on the northern coast of the Peloponnese

. An initial confederation existed during the 5th through the 4th centuries BC. The Achaean League was reformed early in the 3rd century BC, and soon expanded beyond its Achaean heartland. The League's dominance was not to last long, however. During the Third Macedonian War

(171-168 BC), the League flirted with the idea of an alliance with Perseus

, and the Romans

punished it by taking several hostages to ensure good behavior, including Polybius

, the Hellenistic historian who wrote about the rise of the Roman Empire. In 146 BC, the league erupted into open revolt against Roman domination. The Romans

under Lucius Mummius

defeated the Achaeans, razed Corinth

and dissolved the league. Lucius Mummius received the cognomen

Achaicus ("conqueror of Achaea") for his role.

was a civilization

that grew from a small agricultural community founded on the Italian Peninsula

circa the 9th century BC to a massive empire

straddling the Mediterranean Sea

. In its twelve-century existence, Roman civilization shifted from a monarchy

, to a republic

based on a combination of oligarchy

and democracy

, to an autocratic

empire

. It came to dominate Western Europe

and the entire area surrounding the Mediterranean Sea through conquest

and assimilation

.

were a series of three wars fought between Rome

and Carthage

. The main cause of the Punic Wars was the clash of interests between the existing Carthaginian Empire and the expanding Roman sphere of influence. The Romans were initially interested in expansion via Sicily

, part of which lay under Carthaginian control. At the start of the first Punic War

, Carthage was the dominant power of the Mediterranean

, with an extensive maritime empire, while Rome was the rapidly ascending power in Italy

. By the end of the third war, after the deaths of many hundreds of thousands of soldiers from both sides, Rome had conquered Carthage's empire and razed the city, becoming in the process the most powerful state of the Western Mediterranean. With the end of the Macedonian wars

— which ran concurrently with the Punic wars — and the defeat of the Seleucid Emperor

Antiochus III the Great in the Roman-Syrian War

(Treaty of Apamea

, 188 BC) in the eastern sea, Rome emerged as the dominant Mediterranean power and the most powerful city in the classical world. This was a turning point that meant that the civilization of the ancient Mediterranean would pass to the modern world via Europe instead of Africa.

The Coracle

The Coracle

, a small single-passenger-sized float, has been used in Britain since before the first Roman invasion as noted by the invaders. Coracles are round or oval in shape, made of a wooden frame with a hide stretched over it then tar

red to provide waterproofing. Being so light, an operator can carry the light craft over the shoulder. They are capable of operating in mere inches of water due to the keel-less hull. The early people of Wales used these boats for fishing and light travel and updated models are still in use to this day on the rivers of Scotland

and Wales

.

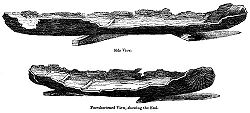

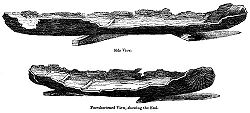

Early Britons also used the world-common hollowed tree trunk canoe

. Examples of these canoes have been found buried in marshes and mud banks of rivers at lengths of upward eight feet.

In 1992 a notable archaeological find, named the "Dover Bronze Age Boat

", was unearthed from beneath what is modern day Dover, England. The Bronze Age

boat which is about 9.5 meters long × 2.3 meters is determined to have been a seagoing vessel. Carbon dating reveals that the craft dating from approximately 1600 BC.

is the oldest known ocean-going boat. The hull was of half oak

logs and side panels also of oak were stitched on with yew

lashings. Both the straight-grained oak and yew bindings are now extinct as a shipbuilding method in England

. A reconstruction in 1996 proved that a crew between four and sixteen paddlers could have easily propelled the boat during Force 4 winds upwards of four knots but with a maximum of 5 knots (10 km/h). The boat could have easily carried a significant amount of cargo and with a strong crew may have been able to traverse near thirty nautical miles in a day.

, or 'people from the North', were people from southern and central Scandinavia

which established states and settlements Northern Europe from the late 8th century to the 11th century.

Viking

s has been a common term for Norsemen in the early medieval period, especially in connection with raids and monastic plundering made by Norsemen in Great Britain and Ireland.

Leif Ericson

was an Iceland

ic explorer known to be the first Europe

an to have landed in North America

(presumably in Newfoundland, Canada

). During a stay in Norway

, Leif Ericsson converted to Christianity

, like many Norse of that time. He also went to Norway to serve the King of Norway, Olaf Tryggvason

. When he returned to Greenland

, he bought the boat of Bjarni Herjólfsson

and set out to explore the land that Bjarni had found (located west

of Greenland), which was, in fact, Newfoundland, in Canada. The Saga of the Greenlanders tells that Leif set out around the year 1000 to follow Bjarni's route with 15 crew members, but going north.

, the world's first tidal dock was built in Lothal

around 2500 BC during the Harappan civilisation at Lothal

near the present day Mangrol harbour on the Gujarat coast. Other ports were probably at Balakot

and Dwarka

. However, it is probable that many small-scale ports, and not massive ports, were used for the Harappan maritime trade. Ships from the harbour at these ancient port cities established trade

with Mesopotamia

, where the Indus Valley was known as Meluhha

.

Emperor Chandragupta Maurya

's Prime Minister

Kautilya's Arthashastra

devotes a full chapter on the state department of waterways under navadhyaksha (Sanskrit

for Superintendent

of ships) . The term, nava dvipantaragamanam (Sanskrit for sailing to other lands by ships) appears in this book in addition to appearing in the Buddhist text, Baudhayana Dharmasastra as the interpretation of the term, Samudrasamyanam.

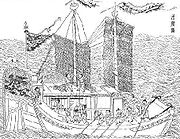

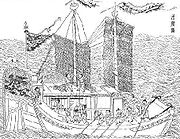

In ancient China, during the Spring and Autumn Period (722 BC–481 BC), large rectangular-based barge

In ancient China, during the Spring and Autumn Period (722 BC–481 BC), large rectangular-based barge

-like ships with layered decks and cabins

with rampart

s acted as floating fortresses on wide rivers and lakes. These were called 'castle ships' ('lou chuan'), yet there were 4 other ship types known in that period, including a ramming

vessel. During the short-lived Qin Dynasty

(221 BC-207 BC) the Chinese sailed south into the South China Sea

during their invasion of Annam, modern Vietnam

.

During the Han Dynasty

(202 BC–220 AD), a ship with a stern

-mounted steering rudder

along with masts and sails was innovated, known as the junk

in Western terminology. The Chinese had been sailing through the Indian Ocean

since the 2nd century BC, with their travels to Kanchipuram

in India

. This was followed up by many recorded maritime travelers following the same route to India, including Faxian

, Zhiyan, Tanwujie, etc. Like in the Western tradition, the earlier Zhou Dynasty

Chinese also made use of the floating pontoon bridge

, which became a valuable means to blockade

the entire Yangtze River during Gongsun Shu's rebellion against the re-established Han government in 33 AD. Although first described in ancient Ptolemaic Egypt, the Song Dynasty

scientist Shen Kuo

(1031–1095) was the first to describe the use of the drydock system in China to repair boats out of water. The canal

pound lock was invented in China

during the previous century, while Shen Kuo

wrote of its effectiveness in his day, writing that ships no longer had the grievances of the old flash lock

design and no longer had to be hauled over long distances (meaning heavier ships with heavier cargo of goods could traverse the waterways of China). There were many other improvements to nautical technology during the Song period as well, including crossbeams bracing the ribs of ships to strengthen them, rudder

s that could be raised or lowered to allow ships to travel in a wider range of water depths, and the teeth of anchors arranged circularly instead of in one direction, "making them more reliable".

Although there were numerous naval battles beforehand, China's first permanent standing navy was established in 1132 during the Song Dynasty

Although there were numerous naval battles beforehand, China's first permanent standing navy was established in 1132 during the Song Dynasty

(960-1279 AD). Gunpowder warfare

at sea was also first known in China, with battles such as the Battle of Caishi

and the Battle of Tangdao

on the Yangtze River in 1161 AD. One of the most important books of medieval maritime literature was Zhu Yu

's Pingzhou Table Talks of 1119 AD. Although the Chinese scientist Shen Kuo

(1031–1095) was the first to describe the magnetic-needle compass

, Zhu Yu's book was the first to specify its use for navigation

at sea. Zhu Yu's book also described watertight bulkhead compartments

in the hull

of Chinese ships, which prevented sinking when heavily damaged in one compartment. Although the drydock was known, Zhu Yu wrote of expert diver

s who were often used to repair boats that were damaged and still submersed in water. Divers in China continued to have a maritime significance, as the later Ming Dynasty

author Song Yingxing

(1587–1666) wrote about pearl divers

who used snorkeling gear (a watertight leather face mask

and breathing tube secured with tin

rings) to breathe underwater

while tied by the waist to the ship in order to be secure while hunting for pearl

s.

.jpg) Japan

Japan

had a navy by at least the 6th century, with their invasions and involvement in political alliances during the Three Kingdoms of Korea

. A joint alliance between the Korean Silla

Kingdom and the Chinese Tang Dynasty

(618-907 AD) heavily defeated the Japanese and their Korean allies of Baekje

in the Battle of Baekgang

on August 27 to August 28 of the year 663 AD. This decisive victory expelled the Japanese force from Korea and allowed the Tang and Silla to conquer Goguryeo

.

Maritime history

Maritime history is the study of human activity at sea. It covers a broad thematic element of history that often uses a global approach, although national and regional histories remain predominant...

dates back thousands of years. In ancient maritime history, the first boats are presumed to have been dugout canoes

Dugout (boat)

A dugout or dugout canoe is a boat made from a hollowed tree trunk. Other names for this type of boat are logboat and monoxylon. Monoxylon is Greek -- mono- + ξύλον xylon -- and is mostly used in classic Greek texts. In Germany they are called einbaum )...

which were developed independently by various stone age populations. In ancient history

Ancient history

Ancient history is the study of the written past from the beginning of recorded human history to the Early Middle Ages. The span of recorded history is roughly 5,000 years, with Cuneiform script, the oldest discovered form of coherent writing, from the protoliterate period around the 30th century BC...

, various vessels were used for coastal fishing and travel.

Prehistory

Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest is a region in northwestern North America, bounded by the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains on the east. Definitions of the region vary and there is no commonly agreed upon boundary, even among Pacific Northwesterners. A common concept of the...

are very skilled at crafting wood. Best known for totem poles up to 80 feet (24 m) tall, they also construct dugout canoes over 60 feet (18.3 m) long for everyday use and ceremonial purposes.

The earliest seaworthy boats may have been developed as early as 45,000 years ago, according to one hypothesis explaining the habitation of Australia

Prehistory of Australia

The prehistory of Australia is the period between the first human habitation of the Australian continent and the first definitive sighting of Australia by Europeans in 1606, which may be taken as the beginning of the recent history of Australia...

. In the history of whaling

History of whaling

The history of whaling is very extensive, stretching back for millennia. This article discusses the history of whaling up to the commencement of the International Whaling Commission moratorium on commercial whaling in 1986....

, humans began whaling in pre-historic times. The oldest known method of catching whales is to simply drive them ashore by placing a number of small boats between the whale and the open sea and attempting to frighten them with noise, activity, and perhaps small, non-lethal weapons such as arrows. Typically, this was used for small species, such as Pilot Whales, Belugas and Narwhals.

The earliest known reference to an organization devoted to ships in ancient India

History of India

The history of India begins with evidence of human activity of Homo sapiens as long as 75,000 years ago, or with earlier hominids including Homo erectus from about 500,000 years ago. The Indus Valley Civilization, which spread and flourished in the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent from...

is to the Mauryan Empire from the 4th century BC. It is believed that the navigation as a science originated on the river Indus some 5000 years ago.

Egypt

Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt was an ancient civilization of Northeastern Africa, concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in what is now the modern country of Egypt. Egyptian civilization coalesced around 3150 BC with the political unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under the first pharaoh...

ians had knowledge to some extent of sail

Sail

A sail is any type of surface intended to move a vessel, vehicle or rotor by being placed in a wind—in essence a propulsion wing. Sails are used in sailing.-History of sails:...

construction. This is governed by the science of aerodynamics

Aerodynamics

Aerodynamics is a branch of dynamics concerned with studying the motion of air, particularly when it interacts with a moving object. Aerodynamics is a subfield of fluid dynamics and gas dynamics, with much theory shared between them. Aerodynamics is often used synonymously with gas dynamics, with...

. A primary feature of a properly designed sail is an amount of "draft

Draft (sailing)

In nautical parlance, the draft or draught of a sail is a degree of curvature in a horizontal cross-section. Any sail experiences a force from the prevailing wind just because it impedes the air's passage...

", caused by curvature of the surface of the sail. According to the Greek

Greece

Greece , officially the Hellenic Republic , and historically Hellas or the Republic of Greece in English, is a country in southeastern Europe....

historian Herodotus

Herodotus

Herodotus was an ancient Greek historian who was born in Halicarnassus, Caria and lived in the 5th century BC . He has been called the "Father of History", and was the first historian known to collect his materials systematically, test their accuracy to a certain extent and arrange them in a...

, Necho II sent out an expedition of Phoenicians, which in three years sailed from the Red Sea

Red Sea

The Red Sea is a seawater inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. The connection to the ocean is in the south through the Bab el Mandeb strait and the Gulf of Aden. In the north, there is the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and the Gulf of Suez...

around Africa

Africa

Africa is the world's second largest and second most populous continent, after Asia. At about 30.2 million km² including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of the Earth's total surface area and 20.4% of the total land area...

to the mouth of the Nile

Nile

The Nile is a major north-flowing river in North Africa, generally regarded as the longest river in the world. It is long. It runs through the ten countries of Sudan, South Sudan, Burundi, Rwanda, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Tanzania, Kenya, Ethiopia, Uganda and Egypt.The Nile has two major...

. Many current historians tend to believe Herodotus on this point, even though he himself was in disbelief that the Phoenicians had accomplished the act, arguing that his doubts mainly originated in the news the sailors had seen the Sun in the north and that he would definitely have counted so fantastic an assertion a typical example of some seafarers' cock-and-bull story and therefore never have mentioned it, at all, had it not been based on facts and made with the according insistence. The Egyptologist Alan Lloyd suggests that the Greeks at this time understood that anyone going south far enough and then turning west would have the Sun on their right but found it unbelievable that Africa reached so far south. He suggests that "It is extremely unlikely that an Egyptian king would, or could, have acted as Necho is depicted as doing" and that the story might have been triggered by the failure of Sataspes' attempt to circumnavigate Africa under Xerxes the Great.

Hannu

Hannu

Hennu or Henenu was an Egyptian noble, serving as m-r-pr "majordomus" under Mentuhotep II and Mentuhotep III in the 21st to 20th century BC. He reportedly re-opened the trade routes to Punt and Libya for the Middle Kingdom of Egypt....

was an ancient Egyptian explorer

Exploration

Exploration is the act of searching or traveling around a terrain for the purpose of discovery of resources or information. Exploration occurs in all non-sessile animal species, including humans...

(around 2750 BC) and the first explorer of whom there is any knowledge. He made the first recorded exploring expedition and wrote his account of the exploration in stone. He traveled along the Red Sea

Red Sea

The Red Sea is a seawater inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. The connection to the ocean is in the south through the Bab el Mandeb strait and the Gulf of Aden. In the north, there is the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and the Gulf of Suez...

to Punt and sailed to what is now part of eastern Ethiopia

Ethiopia

Ethiopia , officially known as the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a country located in the Horn of Africa. It is the second-most populous nation in Africa, with over 82 million inhabitants, and the tenth-largest by area, occupying 1,100,000 km2...

and Somalia

Somalia

Somalia , officially the Somali Republic and formerly known as the Somali Democratic Republic under Socialist rule, is a country located in the Horn of Africa. Since the outbreak of the Somali Civil War in 1991 there has been no central government control over most of the country's territory...

. He returned to Egypt with great treasures, including precious myrrh

Myrrh

Myrrh is the aromatic oleoresin of a number of small, thorny tree species of the genus Commiphora, which grow in dry, stony soil. An oleoresin is a natural blend of an essential oil and a resin. Myrrh resin is a natural gum....

, metal and wood.

The Sea Peoples

Sea Peoples

The Sea Peoples were a confederacy of seafaring raiders of the second millennium BC who sailed into the eastern Mediterranean, caused political unrest, and attempted to enter or control Egyptian territory during the late 19th dynasty and especially during year 8 of Ramesses III of the 20th Dynasty...

was a confederacy

Confederation

A confederation in modern political terms is a permanent union of political units for common action in relation to other units. Usually created by treaty but often later adopting a common constitution, confederations tend to be established for dealing with critical issues such as defense, foreign...

of seafaring raiders who sailed into the eastern shores of the Mediterranean, caused political unrest, and attempted to enter or control Egypt

Egypt

Egypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

ian territory during the late 19th dynasty

Nineteenth dynasty of Egypt

The Nineteenth Dynasty of ancient Egypt was one of the periods of the Egyptian New Kingdom. Founded by Vizier Ramesses I, whom Pharaoh Horemheb chose as his successor to the throne, this dynasty is best known for its military conquests in Palestine, Lebanon, and Syria.The warrior kings of the...

, and especially during Year 8 of Ramesses III of the 20th Dynasty

Twentieth dynasty of Egypt

The Eighteenth, Nineteenth, and Twentieth Dynasties of ancient Egypt are often combined under the group title, New Kingdom. This dynasty is considered to be the last one of the New Kingdom of Egypt, and was followed by the Third Intermediate Period....

. The Egyptian Pharaoh Merneptah

Merneptah

Merneptah was the fourth ruler of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Ancient Egypt. He ruled Egypt for almost ten years between late July or early August 1213 and May 2, 1203 BC, according to contemporary historical records...

explicitly refers to them by the term "the foreign-countries (or 'peoples') of the sea" in his Great Karnak Inscription

Great Karnak Inscription

Located on the wall of the Cachette Court, in the Precinct of Amun-Re of the Karnak temple complex, in modern Luxor, the Great Karnak Inscription of Merneptah is a record of the campaigns of this king against the Sea Peoples....

. Although some scholars believe that they "invaded" Cyprus

Cyprus

Cyprus , officially the Republic of Cyprus , is a Eurasian island country, member of the European Union, in the Eastern Mediterranean, east of Greece, south of Turkey, west of Syria and north of Egypt. It is the third largest island in the Mediterranean Sea.The earliest known human activity on the...

, Hati

Hati

In Norse mythology, Hati Hróðvitnisson is a wolf that according to Gylfaginning chases the Moon across the night sky, just as the wolf Sköll chases the Sun during the day, until the time of Ragnarök when they will swallow these heavenly bodies, after which Fenrir will break free from his bonds and...

and the Levant

Levant

The Levant or ) is the geographic region and culture zone of the "eastern Mediterranean littoral between Anatolia and Egypt" . The Levant includes most of modern Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Israel, the Palestinian territories, and sometimes parts of Turkey and Iraq, and corresponds roughly to the...

, this hypothesis is disputed.

Kingdom of Punt

In ancient times the Kingdom of PuntLand of Punt

The Land of Punt, also called Pwenet, or Pwene by the ancient Egyptians, was a trading partner known for producing and exporting gold, aromatic resins, African blackwood, ebony, ivory, slaves and wild animals...

, which is believed by several Egyptologists to have been situated in the area of modern-day Somalia

Somalia

Somalia , officially the Somali Republic and formerly known as the Somali Democratic Republic under Socialist rule, is a country located in the Horn of Africa. Since the outbreak of the Somali Civil War in 1991 there has been no central government control over most of the country's territory...

, had a steady trade link with the Ancient Egyptians and exported the precious natural resources such as myrrh

Myrrh

Myrrh is the aromatic oleoresin of a number of small, thorny tree species of the genus Commiphora, which grow in dry, stony soil. An oleoresin is a natural blend of an essential oil and a resin. Myrrh resin is a natural gum....

, frankincense

Frankincense

Frankincense, also called olibanum , is an aromatic resin obtained from trees of the genus Boswellia, particularly Boswellia sacra, B. carteri, B. thurifera, B. frereana, and B. bhaw-dajiana...

and gum

Gum

-Natural gums:* Natural gum, any of a number of naturally occurring resinous materials in vegetative species* Gum anima* Gum arabic, used as food additive, adhesive et al.* Cassia gum* Dammar gum* Gellan gum* Guar gum* Kauri gum* Locust bean gum* Spruce gum...

. This trade network continued all the way into the classical era

Classical antiquity

Classical antiquity is a broad term for a long period of cultural history centered on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ancient Greece and ancient Rome, collectively known as the Greco-Roman world...

. The city states of Mossylon, Opone, Malao, Mundus

Mundus

Mundus was an East Roman general during the reign of Justinian I.- Origin and early life :Mundus was of the son of Giesmus, a king of the Gepids, and nephew to another Gepid king, Trapstila. The exact date of his birth is unknown. His father was killed in battle against the Ostrogoths of Theoderic...

and Tabae

Tabae

Tabae is a Catholic titular see. The original diocese was in Caria, a suffragan of Stauropolis; according to Strabo it was located in a plain in Phrygia on the boundaries of Caria. The place is now Tavas, near Kale, Denizli in Turkey; some inscriptions and numerous ancient remains have been...

in Somalia engaged in a lucrative trade network connecting Somali

Somali people

Somalis are an ethnic group located in the Horn of Africa, also known as the Somali Peninsula. The overwhelming majority of Somalis speak the Somali language, which is part of the Cushitic branch of the Afro-Asiatic language family...

merchants with Phoenicia

Phoenicia

Phoenicia , was an ancient civilization in Canaan which covered most of the western, coastal part of the Fertile Crescent. Several major Phoenician cities were built on the coastline of the Mediterranean. It was an enterprising maritime trading culture that spread across the Mediterranean from 1550...

, Ptolemic Egypt

Ptolemaic Kingdom

The Ptolemaic Kingdom in and around Egypt began following Alexander the Great's conquest in 332 BC and ended with the death of Cleopatra VII and the Roman conquest in 30 BC. It was founded when Ptolemy I Soter declared himself Pharaoh of Egypt, creating a powerful Hellenistic state stretching from...

, Greece

Greece

Greece , officially the Hellenic Republic , and historically Hellas or the Republic of Greece in English, is a country in southeastern Europe....

, Parthian Persia

Parthia

Parthia is a region of north-eastern Iran, best known for having been the political and cultural base of the Arsacid dynasty, rulers of the Parthian Empire....

, Saba

Sabaeans

The Sabaeans or Sabeans were an ancient people speaking an Old South Arabian language who lived in what is today Yemen, in the south west of the Arabian Peninsula.Some scholars suggest a link between the Sabaeans and the Biblical land of Sheba....

, Nabataea and the Roman Empire

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of the ancient Roman civilization, characterised by an autocratic form of government and large territorial holdings in Europe and around the Mediterranean....

. Somali sailors used the ancient Somali maritime vessel known as the beden

Beden

The Beden is an ancient Somali maritime vessel that remains the longest surviving sewn ship in East Africa. Its shipyards predominantly lie in the Hafun region, and the ship's modern usage is chiefly for fishing. The ship's construction style is unique to Somalia and significantly differs from...

to transport their cargo.

The Mediterranean

MinoanMinoan civilization

The Minoan civilization was a Bronze Age civilization that arose on the island of Crete and flourished from approximately the 27th century BC to the 15th century BC. It was rediscovered at the beginning of the 20th century through the work of the British archaeologist Arthur Evans...

traders from Crete

Crete

Crete is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, and one of the thirteen administrative regions of Greece. It forms a significant part of the economy and cultural heritage of Greece while retaining its own local cultural traits...

were active in the eastern Mediterranean by the 2nd millennium BC. The Phoenicia

Phoenicia

Phoenicia , was an ancient civilization in Canaan which covered most of the western, coastal part of the Fertile Crescent. Several major Phoenician cities were built on the coastline of the Mediterranean. It was an enterprising maritime trading culture that spread across the Mediterranean from 1550...

ns were an ancient civilization

Civilization

Civilization is a sometimes controversial term that has been used in several related ways. Primarily, the term has been used to refer to the material and instrumental side of human cultures that are complex in terms of technology, science, and division of labor. Such civilizations are generally...

centered in the north of ancient Canaan

Canaan

Canaan is a historical region roughly corresponding to modern-day Israel, Palestine, Lebanon, and the western parts of Jordan...

, with its heartland along the coast of modern day Lebanon

Lebanon

Lebanon , officially the Republic of LebanonRepublic of Lebanon is the most common term used by Lebanese government agencies. The term Lebanese Republic, a literal translation of the official Arabic and French names that is not used in today's world. Arabic is the most common language spoken among...

, Syria

Syria

Syria , officially the Syrian Arab Republic , is a country in Western Asia, bordering Lebanon and the Mediterranean Sea to the West, Turkey to the north, Iraq to the east, Jordan to the south, and Israel to the southwest....

and northern Israel

Israel

The State of Israel is a parliamentary republic located in the Middle East, along the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea...

. Phoenician civilization was an enterprising maritime trading culture

Thalassocracy

The term thalassocracy refers to a state with primarily maritime realms—an empire at sea, such as Athens or the Phoenician network of merchant cities...

that spread across the Mediterranean during the first millennium BC, between the period of 1200 BC to 900 BC. Though ancient boundaries of such city-centered cultures fluctuated, the city of Tyre seems to have been the southernmost. Sarepta

Sarepta

Sarepta was a Phoenician city on the Mediterranean coast between Sidon and Tyre. Most of the objects by which we characterise Phoenician culture are those that have been recovered scattered among Phoenician colonies and trading posts; such carefully excavated colonial sites are in Spain, Sicily,...

between Sidon

Sidon

Sidon or Saïda is the third-largest city in Lebanon. It is located in the South Governorate of Lebanon, on the Mediterranean coast, about 40 km north of Tyre and 40 km south of the capital Beirut. In Genesis, Sidon is the son of Canaan the grandson of Noah...

and Tyre, is the most thoroughly excavated city of the Phoenician homeland. The Phoenicians often traded by means of a galley, a man-powered sailing vessel. They were the first civilization to create the bireme. There is still debate on the subject of whether the Canaanites and Phoenicians were different peoples or not.

The Mediterranean was the source of the vessel, galley, developed before 1000 BC, and development of nautical technology supported the expansion of Mediterranean culture. The Greek

Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece is a civilization belonging to a period of Greek history that lasted from the Archaic period of the 8th to 6th centuries BC to the end of antiquity. Immediately following this period was the beginning of the Early Middle Ages and the Byzantine era. Included in Ancient Greece is the...

trireme

Trireme

A trireme was a type of galley, a Hellenistic-era warship that was used by the ancient maritime civilizations of the Mediterranean, especially the Phoenicians, ancient Greeks and Romans.The trireme derives its name from its three rows of oars on each side, manned with one man per oar...

was the most common ship of the ancient Mediterranean world, employing the propulsion power of oar

Oar

An oar is an implement used for water-borne propulsion. Oars have a flat blade at one end. Oarsmen grasp the oar at the other end. The difference between oars and paddles are that paddles are held by the paddler, and are not connected with the vessel. Oars generally are connected to the vessel by...

smen. Mediterranean peoples developed lighthouse

Lighthouse

A lighthouse is a tower, building, or other type of structure designed to emit light from a system of lamps and lenses or, in older times, from a fire, and used as an aid to navigation for maritime pilots at sea or on inland waterways....

technology and built large fire-based lighthouses, most notably the Lighthouse of Alexandria

Lighthouse of Alexandria

The Lighthouse of Alexandria, also known as the Pharos of Alexandria , was a tower built between 280 and 247 BC on the island of Pharos at Alexandria, Egypt...

, built in the 3rd century BC (between 285 and 247 BC) on the island of Pharos in Alexandria, Egypt.

Many in ancient western societies, such as Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece is a civilization belonging to a period of Greek history that lasted from the Archaic period of the 8th to 6th centuries BC to the end of antiquity. Immediately following this period was the beginning of the Early Middle Ages and the Byzantine era. Included in Ancient Greece is the...

, were in awe of the seas and deified them, believing that man no longer belonged to himself when once he embarked on a sea voyage. They believed that he was liable to be sacrificed at any time to the anger of the great Sea God

Water deity

A water deity is a deity in mythology associated with water or various bodies of water. Water deities are common in mythology and were usually more important among civilizations in which the sea or ocean, or a great river was more important...

. Before the Greeks, the Carians

Carians

The Carians were the ancient inhabitants of Caria in southwest Anatolia.-Historical accounts:It is not clear when the Carians enter into history. The definition is dependent on corresponding Caria and the Carians to the "Karkiya" or "Karkisa" mentioned in the Hittite records...

were an early Mediterranean seagoing people that travelled far. Early writers do not give a good idea about the progress of navigation nor that of the man's seamanship. One of the early stories of seafaring was that of Odysseus

Odysseus

Odysseus or Ulysses was a legendary Greek king of Ithaca and the hero of Homer's epic poem the Odyssey. Odysseus also plays a key role in Homer's Iliad and other works in the Epic Cycle....

.

In Greek mythology

Greek mythology

Greek mythology is the body of myths and legends belonging to the ancient Greeks, concerning their gods and heroes, the nature of the world, and the origins and significance of their own cult and ritual practices. They were a part of religion in ancient Greece...

, the Argonauts

Argonauts

The Argonauts ) were a band of heroes in Greek mythology who, in the years before the Trojan War, accompanied Jason to Colchis in his quest to find the Golden Fleece. Their name comes from their ship, the Argo, which was named after its builder, Argus. "Argonauts", therefore, literally means...

were a band of heroes who, in the years before the Trojan War

Trojan War

In Greek mythology, the Trojan War was waged against the city of Troy by the Achaeans after Paris of Troy took Helen from her husband Menelaus, the king of Sparta. The war is among the most important events in Greek mythology and was narrated in many works of Greek literature, including the Iliad...

, accompanied Jason

Jason

Jason was a late ancient Greek mythological hero from the late 10th Century BC, famous as the leader of the Argonauts and their quest for the Golden Fleece. He was the son of Aeson, the rightful king of Iolcus...

to Colchis

Colchis

In ancient geography, Colchis or Kolkhis was an ancient Georgian state kingdom and region in Western Georgia, which played an important role in the ethnic and cultural formation of the Georgian nation.The Kingdom of Colchis contributed significantly to the development of medieval Georgian...

in his quest to find the Golden Fleece

Golden Fleece

In Greek mythology, the Golden Fleece is the fleece of the gold-haired winged ram, which can be procured in Colchis. It figures in the tale of Jason and his band of Argonauts, who set out on a quest by order of King Pelias for the fleece in order to place Jason rightfully on the throne of Iolcus...

. Their name comes from their ship, the Argo

Argo

In Greek mythology, the Argo was the ship on which Jason and the Argonauts sailed from Iolcos to retrieve the Golden Fleece. It was named after its builder, Argus.-Legend:...

which in turn was named after its builder Argus

ARGUS

ARGUS, all capitalized, may refer to:* ARGUS , a particle physics experiment that ran at DESY* ARGUS distribution, a function used in particle physics named after the above experiment...

. Thus, "Argonauts" literally means "Argo sailors". The voyage of the Greek navigator Pytheas of Massalia

Pytheas

Pytheas of Massalia or Massilia , was a Greek geographer and explorer from the Greek colony, Massalia . He made a voyage of exploration to northwestern Europe at about 325 BC. He travelled around and visited a considerable part of Great Britain...

is an example of a very early voyage. A competent astronomer and geographer, Pytheas ventured from Greece to Western Europe and the British Isles.

The periplus

Periplus

Periplus is the Latinization of an ancient Greek word, περίπλους , literally "a sailing-around." Both segments, peri- and -plous, were independently productive: the ancient Greek speaker understood the word in its literal sense; however, it developed a few specialized meanings, one of which became...

, literally "a sailing-around', in the ancient navigation of Phoenicians, Greeks

Greeks

The Greeks, also known as the Hellenes , are a nation and ethnic group native to Greece, Cyprus and neighboring regions. They also form a significant diaspora, with Greek communities established around the world....

, and Romans

Ancient Rome

Ancient Rome was a thriving civilization that grew on the Italian Peninsula as early as the 8th century BC. Located along the Mediterranean Sea and centered on the city of Rome, it expanded to one of the largest empires in the ancient world....

was a manuscript document that listed in order the ports and coastal landmarks, with approximate distances between, that the captain of a vessel could expect to find along a shore. Several examples of periploi have survived.

The concept of an underwater boat

Submarine

A submarine is a watercraft capable of independent operation below the surface of the water. It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability...

has roots deep in antiquity. The very first report of someone attempting to put the idea into practice seems to have been an attempt by Alexander the Great. According to Aristotle

Aristotle

Aristotle was a Greek philosopher and polymath, a student of Plato and teacher of Alexander the Great. His writings cover many subjects, including physics, metaphysics, poetry, theater, music, logic, rhetoric, linguistics, politics, government, ethics, biology, and zoology...

, Alexander the Great had developed a primitive submersible

Submersible

A submersible is a small vehicle designed to operate underwater. The term submersible is often used to differentiate from other underwater vehicles known as submarines, in that a submarine is a fully autonomous craft, capable of renewing its own power and breathing air, whereas a submersible is...

for reconnaissance missions by 332BC.

Piracy

Piracy

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence at sea. The term can include acts committed on land, in the air, or in other major bodies of water or on a shore. It does not normally include crimes committed against persons traveling on the same vessel as the perpetrator...

, which is a robbery

Robbery

Robbery is the crime of taking or attempting to take something of value by force or threat of force or by putting the victim in fear. At common law, robbery is defined as taking the property of another, with the intent to permanently deprive the person of that property, by means of force or fear....

committed at sea or sometimes on the shore, dates back to Classical Antiquity

Classical antiquity

Classical antiquity is a broad term for a long period of cultural history centered on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ancient Greece and ancient Rome, collectively known as the Greco-Roman world...

and, in all likelihood, much further. The Tyrrhenians

Tyrrhenians

The Tyrrhenians or Tyrsenians is an exonym used by Greek authors to refer to a non-Greek people.- Earliest references :...

, Illyrians

Illyrians

The Illyrians were a group of tribes who inhabited part of the western Balkans in antiquity and the south-eastern coasts of the Italian peninsula...

and Thracians

Thracians

The ancient Thracians were a group of Indo-European tribes inhabiting areas including Thrace in Southeastern Europe. They spoke the Thracian language – a scarcely attested branch of the Indo-European language family...

were known as pirates in ancient times. The island of Lemnos

Lemnos

Lemnos is an island of Greece in the northern part of the Aegean Sea. Administratively the island forms a separate municipality within the Lemnos peripheral unit, which is part of the North Aegean Periphery. The principal town of the island and seat of the municipality is Myrina...

long resisted Greek

Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece is a civilization belonging to a period of Greek history that lasted from the Archaic period of the 8th to 6th centuries BC to the end of antiquity. Immediately following this period was the beginning of the Early Middle Ages and the Byzantine era. Included in Ancient Greece is the...

influence and remained a haven for Thracian pirates. By the 1st century BC, there were pirate states along the Anatolia

Anatolia

Anatolia is a geographic and historical term denoting the westernmost protrusion of Asia, comprising the majority of the Republic of Turkey...

n coast, threatening the commerce

Commerce

While business refers to the value-creating activities of an organization for profit, commerce means the whole system of an economy that constitutes an environment for business. The system includes legal, economic, political, social, cultural, and technological systems that are in operation in any...

of the Roman Empire

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of the ancient Roman civilization, characterised by an autocratic form of government and large territorial holdings in Europe and around the Mediterranean....

.

The Persian Wars

Ionia

Ionia is an ancient region of central coastal Anatolia in present-day Turkey, the region nearest İzmir, which was historically Smyrna. It consisted of the northernmost territories of the Ionian League of Greek settlements...

(the modern Aegean coast of Turkey

Turkey

Turkey , known officially as the Republic of Turkey , is a Eurasian country located in Western Asia and in East Thrace in Southeastern Europe...

) the Greek cities, which included great centres such as Miletus

Miletus

Miletus was an ancient Greek city on the western coast of Anatolia , near the mouth of the Maeander River in ancient Caria...

and Halicarnassus

Halicarnassus

Halicarnassus was an ancient Greek city at the site of modern Bodrum in Turkey. It was located in southwest Caria on a picturesque, advantageous site on the Ceramic Gulf. The city was famous for the tomb of Mausolus, the origin of the word mausoleum, built between 353 BC and 350 BC, and...

, were unable to maintain their independence and came under the rule of the Persian Empire in the mid 6th century BC. In 499 BC the Greeks

Greeks

The Greeks, also known as the Hellenes , are a nation and ethnic group native to Greece, Cyprus and neighboring regions. They also form a significant diaspora, with Greek communities established around the world....

rose in the Ionian Revolt

Ionian Revolt

The Ionian Revolt, and associated revolts in Aeolis, Doris, Cyprus and Caria, were military rebellions by several regions of Asia Minor against Persian rule, lasting from 499 BC to 493 BC...

, and Athens

Athens

Athens , is the capital and largest city of Greece. Athens dominates the Attica region and is one of the world's oldest cities, as its recorded history spans around 3,400 years. Classical Athens was a powerful city-state...

and some other Greek cities went to their aid. In 490 BC the Persian Great King, Darius I

Darius I of Persia

Darius I , also known as Darius the Great, was the third king of kings of the Achaemenid Empire...

, having suppressed the Ionian cities, sent a fleet to punish the Greeks. The Persians landed in Attica

Attica

Attica is a historical region of Greece, containing Athens, the current capital of Greece. The historical region is centered on the Attic peninsula, which projects into the Aegean Sea...

, but were defeated at the Battle of Marathon

Battle of Marathon

The Battle of Marathon took place in 490 BC, during the first Persian invasion of Greece. It was fought between the citizens of Athens, aided by Plataea, and a Persian force commanded by Datis and Artaphernes. It was the culmination of the first attempt by Persia, under King Darius I, to subjugate...

by a Greek army led by the Athenian general Miltiades

Miltiades the Younger

Miltiades the Younger or Miltiades IV was the son of one Cimon, a renowned Olympic chariot-racer. Miltiades considered himself a member of the Aeacidae, and is known mostly for his role in the Battle of Marathon; as well as his rather tragic downfall afterwards. His son Cimon was a major Athenian...

. The burial mound of the Athenian dead can still be seen at Marathon. Ten years later Darius' successor, Xerxes I

Xerxes I of Persia

Xerxes I of Persia , Ḫšayāršā, ), also known as Xerxes the Great, was the fifth king of kings of the Achaemenid Empire.-Youth and rise to power:...

, sent a much more powerful force by land. After being delayed by the Spartan King Leonidas I at Thermopylae

Battle of Thermopylae

The Battle of Thermopylae was fought between an alliance of Greek city-states, led by King Leonidas of Sparta, and the Persian Empire of Xerxes I over the course of three days, during the second Persian invasion of Greece. It took place simultaneously with the naval battle at Artemisium, in August...

, Xerxes advanced into Attica, where he captured and burned Athens. But the Athenians had evacuated the city by sea, and under Themistocles

Themistocles

Themistocles ; c. 524–459 BC, was an Athenian politician and a general. He was one of a new breed of politicians who rose to prominence in the early years of the Athenian democracy, along with his great rival Aristides...

they defeated the Persian fleet at the Battle of Salamis

Battle of Salamis

The Battle of Salamis was fought between an Alliance of Greek city-states and the Persian Empire in September 480 BCE, in the straits between the mainland and Salamis, an island in the Saronic Gulf near Athens...

. A year later, the Greeks, under the Spartan Pausanius

Pausanias (general)

Pausanias was a Spartan general of the 5th century BC. He was the son of Cleombrotus and nephew of Leonidas I, serving as regent after the latter's death, since Leonidas' son Pleistarchus was still under-age. Pausanias was also the father of Pleistoanax, who later became king, and Cleomenes...

, defeated the Persian army at Plataea

Battle of Plataea

The Battle of Plataea was the final land battle during the second Persian invasion of Greece. It took place in 479 BC near the city of Plataea in Boeotia, and was fought between an alliance of the Greek city-states, including Sparta, Athens, Corinth and Megara, and the Persian Empire of Xerxes...

. The Athenian fleet then turned to chasing the Persians out of the Aegean Sea, and in 478 BC they captured Byzantium

Byzantium

Byzantium was an ancient Greek city, founded by Greek colonists from Megara in 667 BC and named after their king Byzas . The name Byzantium is a Latinization of the original name Byzantion...

. In the course of doing so Athens enrolled all the island states and some mainland allies into an alliance, called the Delian League

Delian League

The Delian League, founded in circa 477 BC, was an association of Greek city-states, members numbering between 150 to 173, under the leadership of Athens, whose purpose was to continue fighting the Persian Empire after the Greek victory in the Battle of Plataea at the end of the Greco–Persian Wars...

because its treasury was kept on the sacred island of Delos

Delos

The island of Delos , isolated in the centre of the roughly circular ring of islands called the Cyclades, near Mykonos, is one of the most important mythological, historical and archaeological sites in Greece...

. The Sparta

Sparta

Sparta or Lacedaemon, was a prominent city-state in ancient Greece, situated on the banks of the River Eurotas in Laconia, in south-eastern Peloponnese. It emerged as a political entity around the 10th century BC, when the invading Dorians subjugated the local, non-Dorian population. From c...

ns, although they had taken part in the war, withdrew into isolation after it, allowing Athens to establish unchallenged naval and commercial

Commerce

While business refers to the value-creating activities of an organization for profit, commerce means the whole system of an economy that constitutes an environment for business. The system includes legal, economic, political, social, cultural, and technological systems that are in operation in any...

power.

Achaean League

Achaean League

The Achaean League was a Hellenistic era confederation of Greek city states on the northern and central Peloponnese, which existed between 280 BC and 146 BC...

was a confederation

Confederation

A confederation in modern political terms is a permanent union of political units for common action in relation to other units. Usually created by treaty but often later adopting a common constitution, confederations tend to be established for dealing with critical issues such as defense, foreign...

of Greek

Greece

Greece , officially the Hellenic Republic , and historically Hellas or the Republic of Greece in English, is a country in southeastern Europe....

city state

Polis

Polis , plural poleis , literally means city in Greek. It could also mean citizenship and body of citizens. In modern historiography "polis" is normally used to indicate the ancient Greek city-states, like Classical Athens and its contemporaries, so polis is often translated as "city-state."The...

s in Achaea

Achaea

Achaea is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the region of West Greece. It is situated in the northwestern part of the Peloponnese peninsula. The capital is Patras. The population exceeds 300,000 since 2001.-Geography:...

, a territory on the northern coast of the Peloponnese

Peloponnese

The Peloponnese, Peloponnesos or Peloponnesus , is a large peninsula , located in a region of southern Greece, forming the part of the country south of the Gulf of Corinth...

. An initial confederation existed during the 5th through the 4th centuries BC. The Achaean League was reformed early in the 3rd century BC, and soon expanded beyond its Achaean heartland. The League's dominance was not to last long, however. During the Third Macedonian War

Third Macedonian War

The Third Macedonian War was a war fought between Rome and King Perseus of Macedon. In 179 BC King Philip V of Macedon died and his talented and ambitious son, Perseus, took his throne. Perseus married Laodike, daughter of King Seleucus IV Keraunos of Asia, and increased the size of his army...

(171-168 BC), the League flirted with the idea of an alliance with Perseus

Perseus of Macedon

Perseus was the last king of the Antigonid dynasty, who ruled the successor state in Macedon created upon the death of Alexander the Great...

, and the Romans

Roman Republic

The Roman Republic was the period of the ancient Roman civilization where the government operated as a republic. It began with the overthrow of the Roman monarchy, traditionally dated around 508 BC, and its replacement by a government headed by two consuls, elected annually by the citizens and...

punished it by taking several hostages to ensure good behavior, including Polybius

Polybius

Polybius , Greek ) was a Greek historian of the Hellenistic Period noted for his work, The Histories, which covered the period of 220–146 BC in detail. The work describes in part the rise of the Roman Republic and its gradual domination over Greece...

, the Hellenistic historian who wrote about the rise of the Roman Empire. In 146 BC, the league erupted into open revolt against Roman domination. The Romans

Roman Republic

The Roman Republic was the period of the ancient Roman civilization where the government operated as a republic. It began with the overthrow of the Roman monarchy, traditionally dated around 508 BC, and its replacement by a government headed by two consuls, elected annually by the citizens and...

under Lucius Mummius

Lucius Mummius Achaicus

Lucius Mummius , was a Roman statesman and general, also known as Leucius Mommius. He later received the agnomen Achaicus after conquering Greece.-Praetor:...

defeated the Achaeans, razed Corinth

Corinth

Corinth is a city and former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Corinth, of which it is the seat and a municipal unit...

and dissolved the league. Lucius Mummius received the cognomen

Cognomen

The cognomen nōmen "name") was the third name of a citizen of Ancient Rome, under Roman naming conventions. The cognomen started as a nickname, but lost that purpose when it became hereditary. Hereditary cognomina were used to augment the second name in order to identify a particular branch within...

Achaicus ("conqueror of Achaea") for his role.

Ancient Rome

Ancient RomeAncient Rome

Ancient Rome was a thriving civilization that grew on the Italian Peninsula as early as the 8th century BC. Located along the Mediterranean Sea and centered on the city of Rome, it expanded to one of the largest empires in the ancient world....

was a civilization

Civilization

Civilization is a sometimes controversial term that has been used in several related ways. Primarily, the term has been used to refer to the material and instrumental side of human cultures that are complex in terms of technology, science, and division of labor. Such civilizations are generally...

that grew from a small agricultural community founded on the Italian Peninsula

Italian Peninsula

The Italian Peninsula or Apennine Peninsula is one of the three large peninsulas of Southern Europe , spanning from the Po Valley in the north to the central Mediterranean Sea in the south. The peninsula's shape gives it the nickname Lo Stivale...

circa the 9th century BC to a massive empire

Empire

The term empire derives from the Latin imperium . Politically, an empire is a geographically extensive group of states and peoples united and ruled either by a monarch or an oligarchy....

straddling the Mediterranean Sea

Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean surrounded by the Mediterranean region and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Anatolia and Europe, on the south by North Africa, and on the east by the Levant...

. In its twelve-century existence, Roman civilization shifted from a monarchy

Monarchy

A monarchy is a form of government in which the office of head of state is usually held until death or abdication and is often hereditary and includes a royal house. In some cases, the monarch is elected...

, to a republic

Roman Republic

The Roman Republic was the period of the ancient Roman civilization where the government operated as a republic. It began with the overthrow of the Roman monarchy, traditionally dated around 508 BC, and its replacement by a government headed by two consuls, elected annually by the citizens and...

based on a combination of oligarchy

Oligarchy

Oligarchy is a form of power structure in which power effectively rests with an elite class distinguished by royalty, wealth, family ties, commercial, and/or military legitimacy...

and democracy

Democracy

Democracy is generally defined as a form of government in which all adult citizens have an equal say in the decisions that affect their lives. Ideally, this includes equal participation in the proposal, development and passage of legislation into law...

, to an autocratic

Autocracy

An autocracy is a form of government in which one person is the supreme power within the state. It is derived from the Greek : and , and may be translated as "one who rules by himself". It is distinct from oligarchy and democracy...

empire

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of the ancient Roman civilization, characterised by an autocratic form of government and large territorial holdings in Europe and around the Mediterranean....

. It came to dominate Western Europe

Western Europe

Western Europe is a loose term for the collection of countries in the western most region of the European continents, though this definition is context-dependent and carries cultural and political connotations. One definition describes Western Europe as a geographic entity—the region lying in the...

and the entire area surrounding the Mediterranean Sea through conquest

Invasion

An invasion is a military offensive consisting of all, or large parts of the armed forces of one geopolitical entity aggressively entering territory controlled by another such entity, generally with the objective of either conquering, liberating or re-establishing control or authority over a...

and assimilation

Cultural assimilation

Cultural assimilation is a socio-political response to demographic multi-ethnicity that supports or promotes the assimilation of ethnic minorities into the dominant culture. The term assimilation is often used with regard to immigrants and various ethnic groups who have settled in a new land. New...

.

Punic Wars

The Punic WarsPunic Wars

The Punic Wars were a series of three wars fought between Rome and Carthage from 264 B.C.E. to 146 B.C.E. At the time, they were probably the largest wars that had ever taken place...

were a series of three wars fought between Rome

Ancient Rome

Ancient Rome was a thriving civilization that grew on the Italian Peninsula as early as the 8th century BC. Located along the Mediterranean Sea and centered on the city of Rome, it expanded to one of the largest empires in the ancient world....

and Carthage

Carthage

Carthage , implying it was a 'new Tyre') is a major urban centre that has existed for nearly 3,000 years on the Gulf of Tunis, developing from a Phoenician colony of the 1st millennium BC...

. The main cause of the Punic Wars was the clash of interests between the existing Carthaginian Empire and the expanding Roman sphere of influence. The Romans were initially interested in expansion via Sicily

Sicily

Sicily is a region of Italy, and is the largest island in the Mediterranean Sea. Along with the surrounding minor islands, it constitutes an autonomous region of Italy, the Regione Autonoma Siciliana Sicily has a rich and unique culture, especially with regard to the arts, music, literature,...

, part of which lay under Carthaginian control. At the start of the first Punic War

First Punic War

The First Punic War was the first of three wars fought between Ancient Carthage and the Roman Republic. For 23 years, the two powers struggled for supremacy in the western Mediterranean Sea, primarily on the Mediterranean island of Sicily and its surrounding waters but also to a lesser extent in...

, Carthage was the dominant power of the Mediterranean

Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean surrounded by the Mediterranean region and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Anatolia and Europe, on the south by North Africa, and on the east by the Levant...

, with an extensive maritime empire, while Rome was the rapidly ascending power in Italy

Italy

Italy , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

. By the end of the third war, after the deaths of many hundreds of thousands of soldiers from both sides, Rome had conquered Carthage's empire and razed the city, becoming in the process the most powerful state of the Western Mediterranean. With the end of the Macedonian wars

Macedonian Wars

The Macedonian wars were a series of conflicts fought by Rome in the eastern Mediterranean, the Adriatic, and the Aegean. They resulted in Roman control or influence over the eastern Mediterranean basin, in addition to their hegemony in the western Mediterranean after the Punic wars.-First...

— which ran concurrently with the Punic wars — and the defeat of the Seleucid Emperor

Seleucid Empire

The Seleucid Empire was a Greek-Macedonian state that was created out of the eastern conquests of Alexander the Great. At the height of its power, it included central Anatolia, the Levant, Mesopotamia, Persia, today's Turkmenistan, Pamir and parts of Pakistan.The Seleucid Empire was a major centre...

Antiochus III the Great in the Roman-Syrian War

Roman-Syrian War

The Roman–Syrian War , also known as War of Antiochos or Syrian War, was a military conflict between two coalitions led by the Roman Republic and the Seleucid Empire under Antiochus the Great...

(Treaty of Apamea

Treaty of Apamea

The Treaty of Apamea of 188 BC, was peace treaty between the Roman Republic and Antiochus III , ruler of the Seleucid Empire. It took place after the Romans' victories in the battle of Thermopylae , in the Battle of Magnesia , and after Roman and Rhodian naval victories over the Seleucid navy.In...

, 188 BC) in the eastern sea, Rome emerged as the dominant Mediterranean power and the most powerful city in the classical world. This was a turning point that meant that the civilization of the ancient Mediterranean would pass to the modern world via Europe instead of Africa.

Pre-Roman Britain

Coracle

The coracle is a small, lightweight boat of the sort traditionally used in Wales but also in parts of Western and South Western England, Ireland , and Scotland ; the word is also used of similar boats found in India, Vietnam, Iraq and Tibet...

, a small single-passenger-sized float, has been used in Britain since before the first Roman invasion as noted by the invaders. Coracles are round or oval in shape, made of a wooden frame with a hide stretched over it then tar

Tar

Tar is modified pitch produced primarily from the wood and roots of pine by destructive distillation under pyrolysis. Production and trade in tar was a major contributor in the economies of Northern Europe and Colonial America. Its main use was in preserving wooden vessels against rot. The largest...

red to provide waterproofing. Being so light, an operator can carry the light craft over the shoulder. They are capable of operating in mere inches of water due to the keel-less hull. The early people of Wales used these boats for fishing and light travel and updated models are still in use to this day on the rivers of Scotland

Scotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

and Wales

Wales

Wales is a country that is part of the United Kingdom and the island of Great Britain, bordered by England to its east and the Atlantic Ocean and Irish Sea to its west. It has a population of three million, and a total area of 20,779 km²...

.

Early Britons also used the world-common hollowed tree trunk canoe

Canoe

A canoe or Canadian canoe is a small narrow boat, typically human-powered, though it may also be powered by sails or small electric or gas motors. Canoes are usually pointed at both bow and stern and are normally open on top, but can be decked over A canoe (North American English) or Canadian...

. Examples of these canoes have been found buried in marshes and mud banks of rivers at lengths of upward eight feet.

In 1992 a notable archaeological find, named the "Dover Bronze Age Boat

Dover Bronze Age Boat

Dover Bronze Age boat is one of the few Bronze Age boats to be found in Britain. It dates to 1575-1520BC. The boat was made using oak planks sewn together with yew lashings. This technique has a long tradition of use in British prehistory; the oldest known examples are from Ferriby in east Yorkshire...

", was unearthed from beneath what is modern day Dover, England. The Bronze Age

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a period characterized by the use of copper and its alloy bronze as the chief hard materials in the manufacture of some implements and weapons. Chronologically, it stands between the Stone Age and Iron Age...

boat which is about 9.5 meters long × 2.3 meters is determined to have been a seagoing vessel. Carbon dating reveals that the craft dating from approximately 1600 BC.

16th century BC

The 16th century BC is a century which lasted from 1600 BC to 1501 BC.-Events:* 1700 BC – 1500 BC: Hurrian conquests.* 1595 BC: Sack of Babylon by the Hittite king Mursilis I....