Charles L. McNary

Encyclopedia

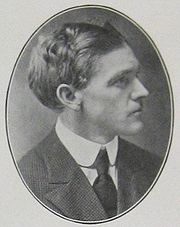

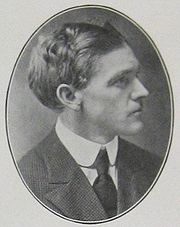

Charles Linza McNary was a United States Republican

politician from Oregon

. He served in the Senate

from 1917 to 1944, and was Senate Minority Leader

from 1933 to 1944. In the Senate, McNary helped to pass legislation that led to the construction of Bonneville Dam

on the Columbia River

, and worked on agricultural and forestry issues. He also supported many of the New Deal

programs at the beginning of the Great Depression

. Until Mark O. Hatfield surpassed his mark in 1993, he was Oregon’s longest serving senator.

McNary was the Republican vice presidential candidate in 1940, on the ticket

with presidential candidate Wendell Willkie

. They lost to the Democratic ticket, composed of Franklin D. Roosevelt

, who was running for his third term as president, paired with Henry A. Wallace

. McNary was a justice of the Oregon Supreme Court

from 1913 to 1915 and was dean of Willamette University College of Law

, in his hometown of Salem

, from 1908 to 1913. Before that, he was a deputy district attorney under his brother John Hugh McNary

, who later became a federal judge for the District of Oregon

.

McNary died in office after unsuccessful surgery on a brain tumor. Oregon held a state funeral for him, during which his body lay in state

at the Oregon State Capitol

in Salem. McNary Dam

, McNary Field

, and McNary High School

in Oregon are named in his honor.

on June 12, 1874. He was the ninth of ten children, and the third son, born to Hugh Linza McNary and Margaret McNary (née

Claggett). When the two married in 1860, Hugh McNary's father-in-law gave him a 112 acre (0.45324832 km²) farm in what is now the city of Keizer

. Charles McNary's paternal grandfather, James McNary, immigrated to the Oregon Country

from Kentucky

in 1845, while his maternal grandfather and namesake, Charles Claggett, immigrated from Missouri

in 1852.

McNary's father helped on the family farm, then taught school for a few years before returning to farming near Salem. When McNary's mother died in 1878, his father moved the family to Salem where he bought a general merchandise store after being unable to run the family farm because of declining health. Charles, known as Tot, began his education at a one-room school in Keizer and later attended Central School in Salem, living on North Commercial Street. Hugh McNary died in 1883, which made Charles an orphan at the age of nine.

Nina McNary became the head of the household, while other siblings took jobs in order to provide for the family. As a boy, Charles worked as a paperboy

, in an orchard, and at other farming tasks. He met Herbert Hoover

, a future U.S. president, who moved to Salem in 1888. He later worked in the county recorder

's office for his brother John Hugh McNary

, who had been elected as county recorder in 1890, and for a short time attended the Capital Business College. After leaving that school, he enrolled in college preparatory classes at Willamette University

, with an eye towards attending Stanford University

or the University of California. During this time he met Jessie Breyman, whom he began dating, at a social club he helped start. Another member of the club was Oswald West

, a future governor of Oregon

.

to attend Stanford, where he studied law, economics, science, and history while working as a waiter to pay for his housing. He left Stanford and returned to Oregon in 1897 after his family asked him to come home. Back in Salem, he read law under the supervision of his brother John and Samuel L. Hayden, and passed the bar

in 1898. The brothers practiced law together in Salem as McNary & McNary, while John also served as deputy district attorney for Marion County. At this time, Charles bought the old family farm and returned it to the family. From 1909 to 1911 he served as president of the Salem Board of Trade, and in 1909 helped to organize the Salem Fruit Union, an agricultural association.

While still partnered with his brother, McNary began teaching property law

While still partnered with his brother, McNary began teaching property law

at Willamette University College of Law

in the spring of 1899 and courting Jessie Breyman. In 1908, he was hired as its dean

to replace John W. Reynolds. As dean, he worked to enlarge the school and secure additional classroom space. He recruited prominent local attorneys to serve on the faculty and increased the size of the school from four graduates in 1908 to 36 in 1913, his last year as dean. In his drive to make Willamette's law school one of the top programs on the West Coast

, he had it re-located from leased space in office buildings to the university campus.

On November 19, 1902, he married Breyman, the daughter of successful Salem businessman Eugene Breyman. Jessie died on July 3, 1918, in an automobile accident south of Newberg

on her way home to Salem. She had been in Oregon to attend the funeral of her mother and was returning from Portland in the Boise family

's car when it flipped and crushed her. McNary spent several days in Oregon for her funeral and then returned to Washington. Charles and Jessie had no children.

McNary first held public office in 1892 when he became Marion County's

McNary first held public office in 1892 when he became Marion County's

deputy recorder, remaining in the position until 1896. In 1904 he managed his brother John's successful campaign to be district attorney

for the third judicial district of Oregon. John then appointed his younger brother as his deputy, and Charles served as deputy until 1911.

Steve Neal, McNary's biographer, describes McNary as a progressive who stuck with the Republican party in 1910 even when many progressives left the party in favor of West, a Democrat. McNary backed the Progressive Era

reforms—the initiative

, recall

, referendum

, primary election

s, and the direct election

of U.S. senators— of Oregonian William S. U'Ren, and he was an early supporter of public rather than private power companies. After West won the election, he chose McNary to be special legal counsel to Oregon's railroad commission; the appointee used the position to urge lower passenger and freight rates. Meanwhile, McNary maintained friendly relations with both progressive and conservative factions of the Oregon Republicans as well as with West.

In 1913 West appointed McNary to the Oregon Supreme Court

to fill a new position created by the legislature's expansion of the court from five justices to seven. The youngest of the justices at age 38, McNary left the law school and private practice behind. He quickly "established himself as a judicial activist and strong advocate of progressive reform". A supporter of organized labor, McNary "consistently defended the rights of injured workers and was not hesitant about using the bench as an instrument for social change" such as an eight-hour work day for public employees. Trade union

s supported McNary throughout his political career.

Several criminal convictions resulted from a "vice scandal

" that sparked in Portland in November 1912 surrounding the city's gay male subculture; by the time McNary was seated, some convictions had been appealed to the court. He wrote the dissenting opinion in the reversal of the conviction of prominent Portland attorney Edward McAllister. The dissent was emotionally charged and "revealed a deeply seated personal discomfort with same-sex eroticism."

In 1914, the court moved into the new Oregon Supreme Court Building

and McNary filed to run for a full-six year term on the bench

. At that time the office was partisan

, and McNary lost the Republican primary

by a single vote to Henry L. Benson

after several recounts and the discovery of uncounted ballots. After his defeat, he served the remainder of his partial term and left the court in 1915. On July 8, 1916, after a close multi-ballot contest among several contenders, the Republican State Committee members elected McNary to be their chairperson. He was seen as someone who could unify the progressive and conservative wings of the party in Oregon.

elected in the November 1916 general election

. Hughes, a former U.S. Supreme Court

justice and future chief justice, carried Oregon but lost the presidency to incumbent Woodrow Wilson

. When U.S. Senator Harry Lane

died in office on May 23, 1917, it created an opportunity for McNary to redeem himself after his failed bid for election to the Oregon Supreme Court. McNary was among several possible successors considered by Oregon Governor James Withycombe

. The governor preferred someone who supported national women's suffrage and prohibition

, and he shared with McNary an interest in farming. Furthermore, McNary supporters argued that both progressive and conservative factions of the Republican Party would accept McNary and that their unity would give the party the best chance of retaining the Senate seat in the next election. Withycombe appointed McNary to the unexpired term on May 29.

After resigning as state party chairman, McNary prepared to campaign for a full term in the Senate. He faced Speaker of the Oregon House of Representatives

After resigning as state party chairman, McNary prepared to campaign for a full term in the Senate. He faced Speaker of the Oregon House of Representatives

Robert N. Stanfield

in the May 1918 Republican primary. McNary defeated Stanfield 52,546 to 30,999. In the November general election he defeated friend and former governor Oswald West

82,360 to 64,303 to win a full six-year term in the Senate. Meanwhile, Frederick W. Mulkey

won the election to replace McNary and finish Lane's original term that would end in January 1919, and Mulkey took office on November 6, 1918, replacing McNary in that seat.

Shortly after taking office, Mulkey resigned the seat effective December 17, 1918, and McNary was then re-appointed to the Senate on December 12, 1918, and took office on December 18, instead of taking office in January when his term he was elected to would have commenced. Mulkey resigned in order to give McNary a slight seniority edge over other new members of the Senate. In 1920, former adversary Stanfield defeated incumbent Democrat George Earle Chamberlain

for Oregon's other Senate seat, making McNary the state's senior Senator. McNary won re-election four times, in 1924, 1930, 1936, and 1942, serving in Washington, D.C.

, until his death in 1944.

, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson

sought Senate approval of the Treaty of Versailles

. Because the treaty included provisions for establishing and joining the League of Nations

, one of Wilson's Fourteen Points

, Republicans opposed it. Going against much of his party, McNary, part of a group of senators known as "reservationists", proposed minor changes but supported the United States entry into the League. Ultimately, the Senate never ratified the Treaty of Versailles, and the United States never joined the League of Nations.

One of the prime opponents of Wilson and the League of Nations was Senate Majority Leader Henry Cabot Lodge

. After McNary demonstrated his skill in the debate over the League, Lodge took him under his wing and the two formed a longtime friendship. This friendship helped McNary secure favorable committee assignments and ushered him into the inner power circle of the Senate. Early in his career he served as chairman of the Irrigation and Reclamation of Arid Lands Committee, and as a member of the Agriculture and Forestry Committee. In 1922, President Warren G. Harding

asked McNary to be the Secretary of the Interior to replace Albert B. Fall

because of Fall's involvement in the ongoing Teapot Dome scandal

. McNary declined, preferring to stay in the Senate.

In 1933, McNary was selected as the Senate Minority Leader by fellow Republicans when the Senate was under Democratic

In 1933, McNary was selected as the Senate Minority Leader by fellow Republicans when the Senate was under Democratic

control during the New Deal

era. He remained minority leader for the rest of his time in office. As minority leader he "hovered most of the time on the periphery of the Republican left", and he opposed disciplining Republican senators who supported President Franklin Roosevelt. He supported many of the New Deal programs at the beginning of Roosevelt’s presidency. As World War II

approached, he favored "all aid to England and France short of war". He voted to keep an arms embargo

in place, but voted for the lend-lease

agreement with the British in 1941 and to re-instate Selective Service in 1940 in preparation for military conscription

of civilian men.

As early as the 1920s, McNary supported the development of federal hydroelectric power

dams, and in 1933 he introduced legislation that led to the building of the Grand Coulee

and Bonneville

dams on the Columbia as public works projects. He voted in favor of the United States joining the World Court

in 1926. He favored buying more National Forest

lands, re-forestation, fire protection for forests via the Clarke-McNary Act

, and farm support. Although vetoed by President Coolidge

, the McNary-Haugen Farm Relief Bill

was the forerunner of the farm-related parts of the New Deal

.

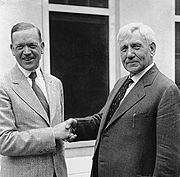

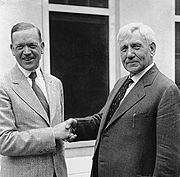

nominee, a western

farm leader chosen to balance the ticket of presidential nominee Wendell Willkie

, a pro-business leader from the east. The two men differed on many issues. Writing for Life magazine shortly before the general election in 1940, Richard L. Neuberger

said, "Whether as Vice President of the U.S. Charley McNary can keep on endorsing Government-power projects, isolation, high tariffs and huge outlays for farm relief under a President who believes in none of these things remains to be seen." McNary's acceptance speech re-iterated his support for the Tennessee Valley Authority

, a federally owned power-producing corporation that Willkie as "the head of a far-flung [private] utilities empire" had opposed. During the campaign, McNary promoted farming issues and criticized foreign trade agreements that he said had "closed European markets to our grain, meat, fruits and fiber." The Willkie–McNary ticket lost the Electoral College

to President Roosevelt

and Henry A. Wallace

, 449 to 82.

, in her hometown of Washington, D.C.

Before the marriage, she worked as his private secretary. As with his first marriage, his second did not produce children, but Charles and Cornelia adopted a daughter named Charlotte in 1935.

In 1926, McNary built a new $6,000 ranch-style house, which he designed himself, along two creeks on his farm north of Salem. His estate, called "Fir Cone", featured a putting green, rose garden, tennis court, fishpond, and arboretum

In 1926, McNary built a new $6,000 ranch-style house, which he designed himself, along two creeks on his farm north of Salem. His estate, called "Fir Cone", featured a putting green, rose garden, tennis court, fishpond, and arboretum

, and more than 250 acres (1 km²) of trees. Fir Cone was described as Oregon's Monticello

by later Senator Richard L. Neuberger, as it hosted many meetings with politicians from the national stage. The farm included 110 acre (0.4451546 km²) of nut and fruit orchards, through which McNary helped establish the filbert industry in Oregon and on which he developed the Imperial prune

.

After complaining of headaches and suffering slurred speech beginning in early 1943, McNary went to the Bethesda, Maryland, Naval Hospital

on November 8, 1943, where doctors diagnosed a malignant

brain tumor. They removed it that week, and McNary was released from the hospital on December 2, but the cancer had already spread to other parts of his body. He and his family departed for Fort Lauderdale, Florida

, to spend the winter. He partly recovered from the surgery, but by February 24, 1944, when he was re-elected as Republican senate leader, he was comatose. Charles L. McNary died February 25, 1944, in Fort Lauderdale, and was buried in Belcrest Memorial Cemetery in Salem. He was given a state funeral, during which his body lay in state in the chamber of the Oregon House of Representatives

at the Oregon State Capitol

in Salem.

McNary's running-mate Willkie died six months later. It was the only time both members of a major party presidential ticket

died during the term for which they sought election. At the time of his death, McNary held the record for longest-serving senator from Oregon, a record he kept until 1993 when Mark O. Hatfield surpassed his mark of 9,726 days in office.

McNary Dam

on the Columbia River between Oregon and Washington is named after him, as is McNary Field

, Salem's airport. McNary High School

in Keizer

and McNary Residence Hall at Oregon State University

are also named in his honor.

Republican Party (United States)

The Republican Party is one of the two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Democratic Party. Founded by anti-slavery expansion activists in 1854, it is often called the GOP . The party's platform generally reflects American conservatism in the U.S...

politician from Oregon

Oregon

Oregon is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is located on the Pacific coast, with Washington to the north, California to the south, Nevada on the southeast and Idaho to the east. The Columbia and Snake rivers delineate much of Oregon's northern and eastern...

. He served in the Senate

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

from 1917 to 1944, and was Senate Minority Leader

Party leaders of the United States Senate

The Senate Majority and Minority Leaders are two United States Senators who are elected by the party conferences that hold the majority and the minority respectively. These leaders serve as the chief Senate spokespeople for their parties and manage and schedule the legislative and executive...

from 1933 to 1944. In the Senate, McNary helped to pass legislation that led to the construction of Bonneville Dam

Bonneville Dam

Bonneville Lock and Dam consists of several run-of-the-river dam structures that together complete a span of the Columbia River between the U.S. states of Oregon and Washington at River Mile 146.1. The dam is located east of Portland, Oregon, in the Columbia River Gorge. The primary functions of...

on the Columbia River

Columbia River

The Columbia River is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The river rises in the Rocky Mountains of British Columbia, Canada, flows northwest and then south into the U.S. state of Washington, then turns west to form most of the border between Washington and the state...

, and worked on agricultural and forestry issues. He also supported many of the New Deal

New Deal

The New Deal was a series of economic programs implemented in the United States between 1933 and 1936. They were passed by the U.S. Congress during the first term of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The programs were Roosevelt's responses to the Great Depression, and focused on what historians call...

programs at the beginning of the Great Depression

Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe worldwide economic depression in the decade preceding World War II. The timing of the Great Depression varied across nations, but in most countries it started in about 1929 and lasted until the late 1930s or early 1940s...

. Until Mark O. Hatfield surpassed his mark in 1993, he was Oregon’s longest serving senator.

McNary was the Republican vice presidential candidate in 1940, on the ticket

Ticket (election)

A ticket refers to a single election choice which fills more than one political office or seat. For example, in the U.S., the candidates for President and Vice President run on the same "ticket", because they are elected together on a single ballot question rather than separately.A ticket can also...

with presidential candidate Wendell Willkie

Wendell Willkie

Wendell Lewis Willkie was a corporate lawyer in the United States and a dark horse who became the Republican Party nominee for the president in 1940. A member of the liberal wing of the GOP, he crusaded against those domestic policies of the New Deal that he thought were inefficient and...

. They lost to the Democratic ticket, composed of Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt , also known by his initials, FDR, was the 32nd President of the United States and a central figure in world events during the mid-20th century, leading the United States during a time of worldwide economic crisis and world war...

, who was running for his third term as president, paired with Henry A. Wallace

Henry A. Wallace

Henry Agard Wallace was the 33rd Vice President of the United States , the Secretary of Agriculture , and the Secretary of Commerce . In the 1948 presidential election, Wallace was the nominee of the Progressive Party.-Early life:Henry A...

. McNary was a justice of the Oregon Supreme Court

Oregon Supreme Court

The Oregon Supreme Court is the highest state court in the U.S. state of Oregon. The only court that may reverse or modify a decision of the Oregon Supreme Court is the Supreme Court of the United States. The OSC holds court at the Oregon Supreme Court Building in Salem, Oregon, near the capitol...

from 1913 to 1915 and was dean of Willamette University College of Law

Willamette University College of Law

Willamette University College of Law is a private law school located in Salem, Oregon, United States. Founded in 1842, Willamette University is the oldest university in the Western United States...

, in his hometown of Salem

Salem, Oregon

Salem is the capital of the U.S. state of Oregon, and the county seat of Marion County. It is located in the center of the Willamette Valley alongside the Willamette River, which runs north through the city. The river forms the boundary between Marion and Polk counties, and the city neighborhood...

, from 1908 to 1913. Before that, he was a deputy district attorney under his brother John Hugh McNary

John Hugh McNary

John Hugh McNary was an American attorney and jurist in the state of Oregon. He served as the federal judge for the United States District Court for the District of Oregon in Portland. A native of Oregon, he also served as a district attorney and as an assistant district attorney in Salem, Oregon...

, who later became a federal judge for the District of Oregon

United States District Court for the District of Oregon

The United States District Court for the District of Oregon is the Federal district court whose jurisdiction comprises the state of Oregon. It was created in 1859 when the state was admitted to the Union...

.

McNary died in office after unsuccessful surgery on a brain tumor. Oregon held a state funeral for him, during which his body lay in state

Lying in state

Lying in state is a term used to describe the tradition in which a coffin is placed on view to allow the public at large to pay their respects to the deceased. It traditionally takes place in the principal government building of a country or city...

at the Oregon State Capitol

Oregon State Capitol

The Oregon State Capitol is the building housing the state legislature and the offices of the governor, secretary of state, and treasurer of the U.S. state of Oregon. It is located in the state capital, Salem. The current building, constructed from 1936 to 1938, and expanded in 1977, is the third...

in Salem. McNary Dam

McNary Dam

McNary Dam is a 1.4-mile long concrete gravity run-of-the-river dam which spans the Columbia River. It joins Umatilla County, Oregon with Benton County, Washington, 292 miles upriver from the mouth of the Columbia at Astoria, Oregon. It is operated by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers' McNary...

, McNary Field

McNary Field

McNary Field , also known as Salem Municipal Airport, is a public airport located two miles southeast of the central business district of Salem, a city in Marion County, Oregon, United States, also the capital of the state. The airport is named for Senator Charles L. McNary...

, and McNary High School

McNary High School

McNary High School is a public high school located in Keizer, Oregon, United States. It is named for Charles L. McNary, a U.S. Senator who was from the Keizer area.-Academics:...

in Oregon are named in his honor.

Early life

McNary was born on his maternal grandfather's family farm north of SalemSalem, Oregon

Salem is the capital of the U.S. state of Oregon, and the county seat of Marion County. It is located in the center of the Willamette Valley alongside the Willamette River, which runs north through the city. The river forms the boundary between Marion and Polk counties, and the city neighborhood...

on June 12, 1874. He was the ninth of ten children, and the third son, born to Hugh Linza McNary and Margaret McNary (née

NEE

NEE is a political protest group whose goal was to provide an alternative for voters who are unhappy with all political parties at hand in Belgium, where voting is compulsory.The NEE party was founded in 2005 in Antwerp...

Claggett). When the two married in 1860, Hugh McNary's father-in-law gave him a 112 acre (0.45324832 km²) farm in what is now the city of Keizer

Keizer, Oregon

Keizer is a city in Marion County, Oregon, United States, along the 45th parallel. It was named for Thomas Dove and John Brooks Keizer, two pioneers who arrived in the Wagon Train of 1843, and later filed donation land claims. The population was 36,278 at the 2010 census...

. Charles McNary's paternal grandfather, James McNary, immigrated to the Oregon Country

Oregon Country

The Oregon Country was a predominantly American term referring to a disputed ownership region of the Pacific Northwest of North America. The region was occupied by British and French Canadian fur traders from before 1810, and American settlers from the mid-1830s, with its coastal areas north from...

from Kentucky

Kentucky

The Commonwealth of Kentucky is a state located in the East Central United States of America. As classified by the United States Census Bureau, Kentucky is a Southern state, more specifically in the East South Central region. Kentucky is one of four U.S. states constituted as a commonwealth...

in 1845, while his maternal grandfather and namesake, Charles Claggett, immigrated from Missouri

Missouri

Missouri is a US state located in the Midwestern United States, bordered by Iowa, Illinois, Kentucky, Tennessee, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Kansas and Nebraska. With a 2010 population of 5,988,927, Missouri is the 18th most populous state in the nation and the fifth most populous in the Midwest. It...

in 1852.

McNary's father helped on the family farm, then taught school for a few years before returning to farming near Salem. When McNary's mother died in 1878, his father moved the family to Salem where he bought a general merchandise store after being unable to run the family farm because of declining health. Charles, known as Tot, began his education at a one-room school in Keizer and later attended Central School in Salem, living on North Commercial Street. Hugh McNary died in 1883, which made Charles an orphan at the age of nine.

Nina McNary became the head of the household, while other siblings took jobs in order to provide for the family. As a boy, Charles worked as a paperboy

Paperboy

A paperboy is the general name for a person employed by a newspaper, They are often used around the office to run low end errands. They make copies and distribute them. Paperboys traditionally were and are still often portrayed on television and movies as preteen boys, often on a bicycle...

, in an orchard, and at other farming tasks. He met Herbert Hoover

Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover was the 31st President of the United States . Hoover was originally a professional mining engineer and author. As the United States Secretary of Commerce in the 1920s under Presidents Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge, he promoted partnerships between government and business...

, a future U.S. president, who moved to Salem in 1888. He later worked in the county recorder

Recorder of deeds

Recorder of deeds is a government office tasked with maintaining public records and documents, especially records relating to real estate ownership that provide persons other than the owner of a property with real rights over that property.-Background:...

's office for his brother John Hugh McNary

John Hugh McNary

John Hugh McNary was an American attorney and jurist in the state of Oregon. He served as the federal judge for the United States District Court for the District of Oregon in Portland. A native of Oregon, he also served as a district attorney and as an assistant district attorney in Salem, Oregon...

, who had been elected as county recorder in 1890, and for a short time attended the Capital Business College. After leaving that school, he enrolled in college preparatory classes at Willamette University

Willamette University

Willamette University is an American private institution of higher learning located in Salem, Oregon. Founded in 1842, it is the oldest university in the Western United States. Willamette is a member of the Annapolis Group of colleges, and is made up of an undergraduate College of Liberal Arts and...

, with an eye towards attending Stanford University

Stanford University

The Leland Stanford Junior University, commonly referred to as Stanford University or Stanford, is a private research university on an campus located near Palo Alto, California. It is situated in the northwestern Santa Clara Valley on the San Francisco Peninsula, approximately northwest of San...

or the University of California. During this time he met Jessie Breyman, whom he began dating, at a social club he helped start. Another member of the club was Oswald West

Oswald West

Oswald West was an American politician, a Democrat, who served most notably as the 14th Governor of Oregon. Called "Os West" by Oregon writer Stewart Holbrook, who described him as "by all odds the most brilliant governor Oregon ever had."- Early life and career :West was born in Ontario, Canada...

, a future governor of Oregon

Governor of Oregon

The Governor of Oregon is the top executive of the government of the U.S. state of Oregon. The title of governor was also applied to the office of Oregon's chief executive during the provisional and U.S. territorial governments....

.

Legal career

In the autumn of 1896, McNary moved to CaliforniaCalifornia

California is a state located on the West Coast of the United States. It is by far the most populous U.S. state, and the third-largest by land area...

to attend Stanford, where he studied law, economics, science, and history while working as a waiter to pay for his housing. He left Stanford and returned to Oregon in 1897 after his family asked him to come home. Back in Salem, he read law under the supervision of his brother John and Samuel L. Hayden, and passed the bar

Bar association

A bar association is a professional body of lawyers. Some bar associations are responsible for the regulation of the legal profession in their jurisdiction; others are professional organizations dedicated to serving their members; in many cases, they are both...

in 1898. The brothers practiced law together in Salem as McNary & McNary, while John also served as deputy district attorney for Marion County. At this time, Charles bought the old family farm and returned it to the family. From 1909 to 1911 he served as president of the Salem Board of Trade, and in 1909 helped to organize the Salem Fruit Union, an agricultural association.

Property law

Property law is the area of law that governs the various forms of ownership in real property and in personal property, within the common law legal system. In the civil law system, there is a division between movable and immovable property...

at Willamette University College of Law

Willamette University College of Law

Willamette University College of Law is a private law school located in Salem, Oregon, United States. Founded in 1842, Willamette University is the oldest university in the Western United States...

in the spring of 1899 and courting Jessie Breyman. In 1908, he was hired as its dean

Dean (education)

In academic administration, a dean is a person with significant authority over a specific academic unit, or over a specific area of concern, or both...

to replace John W. Reynolds. As dean, he worked to enlarge the school and secure additional classroom space. He recruited prominent local attorneys to serve on the faculty and increased the size of the school from four graduates in 1908 to 36 in 1913, his last year as dean. In his drive to make Willamette's law school one of the top programs on the West Coast

West Coast of the United States

West Coast or Pacific Coast are terms for the westernmost coastal states of the United States. The term most often refers to the states of California, Oregon, and Washington. Although not part of the contiguous United States, Alaska and Hawaii do border the Pacific Ocean but can't be included in...

, he had it re-located from leased space in office buildings to the university campus.

On November 19, 1902, he married Breyman, the daughter of successful Salem businessman Eugene Breyman. Jessie died on July 3, 1918, in an automobile accident south of Newberg

Newberg, Oregon

-Demographics:As of the census of 2000, there were 18,064 people, 6,099 households, and 4,348 families residing in the city. The population density was 3,599.4 people per square mile . There were 6,435 housing units at an average density of 1,282.2 per square mile...

on her way home to Salem. She had been in Oregon to attend the funeral of her mother and was returning from Portland in the Boise family

Reuben P. Boise

Reuben Patrick Boise was an American attorney, judge and politician in the Oregon Territory and the early years of the state of Oregon. A native of Massachusetts, he immigrated to Oregon in 1850, where he would twice serve on the Oregon Supreme Court for a total of 16 years, with three stints as...

's car when it flipped and crushed her. McNary spent several days in Oregon for her funeral and then returned to Washington. Charles and Jessie had no children.

Political career

Marion County, Oregon

Marion County is a county located in the U.S. state of Oregon. It was originally named the Champooick District, after Champoeg, a meeting place on the Willamette River. On September 3, 1849, the territorial legislature renamed it in honor of Francis Marion, a Continental Army general of the...

deputy recorder, remaining in the position until 1896. In 1904 he managed his brother John's successful campaign to be district attorney

District attorney

In many jurisdictions in the United States, a District Attorney is an elected or appointed government official who represents the government in the prosecution of criminal offenses. The district attorney is the highest officeholder in the jurisdiction's legal department and supervises a staff of...

for the third judicial district of Oregon. John then appointed his younger brother as his deputy, and Charles served as deputy until 1911.

Steve Neal, McNary's biographer, describes McNary as a progressive who stuck with the Republican party in 1910 even when many progressives left the party in favor of West, a Democrat. McNary backed the Progressive Era

Progressive Era

The Progressive Era in the United States was a period of social activism and political reform that flourished from the 1890s to the 1920s. One main goal of the Progressive movement was purification of government, as Progressives tried to eliminate corruption by exposing and undercutting political...

reforms—the initiative

Initiative

In political science, an initiative is a means by which a petition signed by a certain minimum number of registered voters can force a public vote...

, recall

Recall election

A recall election is a procedure by which voters can remove an elected official from office through a direct vote before his or her term has ended...

, referendum

Referendum

A referendum is a direct vote in which an entire electorate is asked to either accept or reject a particular proposal. This may result in the adoption of a new constitution, a constitutional amendment, a law, the recall of an elected official or simply a specific government policy. It is a form of...

, primary election

Primary election

A primary election is an election in which party members or voters select candidates for a subsequent election. Primary elections are one means by which a political party nominates candidates for the next general election....

s, and the direct election

Direct election

Direct election is a term describing a system of choosing political officeholders in which the voters directly cast ballots for the person, persons or political party that they desire to see elected. The method by which the winner or winners of a direct election are chosen depends upon the...

of U.S. senators— of Oregonian William S. U'Ren, and he was an early supporter of public rather than private power companies. After West won the election, he chose McNary to be special legal counsel to Oregon's railroad commission; the appointee used the position to urge lower passenger and freight rates. Meanwhile, McNary maintained friendly relations with both progressive and conservative factions of the Oregon Republicans as well as with West.

In 1913 West appointed McNary to the Oregon Supreme Court

Oregon Supreme Court

The Oregon Supreme Court is the highest state court in the U.S. state of Oregon. The only court that may reverse or modify a decision of the Oregon Supreme Court is the Supreme Court of the United States. The OSC holds court at the Oregon Supreme Court Building in Salem, Oregon, near the capitol...

to fill a new position created by the legislature's expansion of the court from five justices to seven. The youngest of the justices at age 38, McNary left the law school and private practice behind. He quickly "established himself as a judicial activist and strong advocate of progressive reform". A supporter of organized labor, McNary "consistently defended the rights of injured workers and was not hesitant about using the bench as an instrument for social change" such as an eight-hour work day for public employees. Trade union

Trade union

A trade union, trades union or labor union is an organization of workers that have banded together to achieve common goals such as better working conditions. The trade union, through its leadership, bargains with the employer on behalf of union members and negotiates labour contracts with...

s supported McNary throughout his political career.

Several criminal convictions resulted from a "vice scandal

Portland vice scandal

The Portland vice scandal refers to the discovery in November 1912 of a gay male subculture in the U.S. city of Portland, Oregon, following the arrest and interrogation of nineteen-year-old Benjamin Trout for shoplifting...

" that sparked in Portland in November 1912 surrounding the city's gay male subculture; by the time McNary was seated, some convictions had been appealed to the court. He wrote the dissenting opinion in the reversal of the conviction of prominent Portland attorney Edward McAllister. The dissent was emotionally charged and "revealed a deeply seated personal discomfort with same-sex eroticism."

In 1914, the court moved into the new Oregon Supreme Court Building

Oregon Supreme Court Building

The Oregon Supreme Court Building is the home to the Oregon Supreme Court, Oregon Court of Appeals, and the Oregon Judicial Department. Located in the state’s capitol of Salem, it is Oregon’s oldest state government building...

and McNary filed to run for a full-six year term on the bench

Bench (law)

Bench in legal contexts means simply the location in a courtroom where a judge sits. The historical roots of that meaning come from the fact that judges formerly sat on long seats or benches when presiding over a court...

. At that time the office was partisan

Partisan (political)

In politics, a partisan is a committed member of a political party. In multi-party systems, the term is widely understood to carry a negative connotation - referring to those who wholly support their party's policies and are perhaps even reluctant to acknowledge correctness on the part of their...

, and McNary lost the Republican primary

Primary election

A primary election is an election in which party members or voters select candidates for a subsequent election. Primary elections are one means by which a political party nominates candidates for the next general election....

by a single vote to Henry L. Benson

Henry L. Benson

Henry Lamdin Benson was an American politician and jurist in the state of Oregon. He was the 44th Associate Justice of the Oregon Supreme Court, serving from 1915 to 1921 on the state's highest court...

after several recounts and the discovery of uncounted ballots. After his defeat, he served the remainder of his partial term and left the court in 1915. On July 8, 1916, after a close multi-ballot contest among several contenders, the Republican State Committee members elected McNary to be their chairperson. He was seen as someone who could unify the progressive and conservative wings of the party in Oregon.

National politics

As chairman of the state's Republican Party, McNary campaigned to get Republican presidential nominee Charles Evans HughesCharles Evans Hughes

Charles Evans Hughes, Sr. was an American statesman, lawyer and Republican politician from New York. He served as the 36th Governor of New York , Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States , United States Secretary of State , a judge on the Court of International Justice , and...

elected in the November 1916 general election

United States presidential election, 1916

The United States presidential election of 1916 took place while Europe was embroiled in World War I. Public sentiment in the still neutral United States leaned towards the British and French forces, due to the harsh treatment of civilians by the German Army, which had invaded and occupied large...

. Hughes, a former U.S. Supreme Court

Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States is the highest court in the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all state and federal courts, and original jurisdiction over a small range of cases...

justice and future chief justice, carried Oregon but lost the presidency to incumbent Woodrow Wilson

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson was the 28th President of the United States, from 1913 to 1921. A leader of the Progressive Movement, he served as President of Princeton University from 1902 to 1910, and then as the Governor of New Jersey from 1911 to 1913...

. When U.S. Senator Harry Lane

Harry Lane

Harry Lane was an American physician and politician in the state of Oregon. A native of the state, he worked as the head of the state insane asylum before entering local politics and served as mayor of Portland...

died in office on May 23, 1917, it created an opportunity for McNary to redeem himself after his failed bid for election to the Oregon Supreme Court. McNary was among several possible successors considered by Oregon Governor James Withycombe

James Withycombe

James Withycombe was a British-born American politician, a Republican, and the 15th Governor of Oregon. Prior to entering politics he was farmer and sheep rancher in the Tualatin Valley, leading to appointment as the state's veterinarian and then as head of what became the Oregon State University...

. The governor preferred someone who supported national women's suffrage and prohibition

Prohibition in the United States

Prohibition in the United States was a national ban on the sale, manufacture, and transportation of alcohol, in place from 1920 to 1933. The ban was mandated by the Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution, and the Volstead Act set down the rules for enforcing the ban, as well as defining which...

, and he shared with McNary an interest in farming. Furthermore, McNary supporters argued that both progressive and conservative factions of the Republican Party would accept McNary and that their unity would give the party the best chance of retaining the Senate seat in the next election. Withycombe appointed McNary to the unexpired term on May 29.

Oregon House of Representatives

The Oregon House of Representatives is the lower house of the Oregon Legislative Assembly. There are 60 members of the House, representing 60 districts across the state, each with a population of 57,000. The House meets at the Oregon State Capitol in Salem....

Robert N. Stanfield

Robert N. Stanfield

Robert Nelson Stanfield was an American politician and rancher from the state of Oregon. A native of the state, he was a rancher before entering politics and serving in the Oregon House of Representatives, including one session as Speaker...

in the May 1918 Republican primary. McNary defeated Stanfield 52,546 to 30,999. In the November general election he defeated friend and former governor Oswald West

Oswald West

Oswald West was an American politician, a Democrat, who served most notably as the 14th Governor of Oregon. Called "Os West" by Oregon writer Stewart Holbrook, who described him as "by all odds the most brilliant governor Oregon ever had."- Early life and career :West was born in Ontario, Canada...

82,360 to 64,303 to win a full six-year term in the Senate. Meanwhile, Frederick W. Mulkey

Frederick W. Mulkey

Frederick William Mulkey was an American attorney and politician from the state of Oregon. A native of Portland, he began his political career on the Portland City Council, serving one year as its president. A Republican, he twice served as a United States Senator from Oregon, filling terms...

won the election to replace McNary and finish Lane's original term that would end in January 1919, and Mulkey took office on November 6, 1918, replacing McNary in that seat.

Shortly after taking office, Mulkey resigned the seat effective December 17, 1918, and McNary was then re-appointed to the Senate on December 12, 1918, and took office on December 18, instead of taking office in January when his term he was elected to would have commenced. Mulkey resigned in order to give McNary a slight seniority edge over other new members of the Senate. In 1920, former adversary Stanfield defeated incumbent Democrat George Earle Chamberlain

George Earle Chamberlain

George Earle Chamberlain was an American politician, legislator, and public official in Oregon. A native of Mississippi and trained lawyer, he served as the 11th Governor of Oregon, a representative in the Oregon Legislative Assembly, a United States Senator.-Early life:Chamberlain was born near...

for Oregon's other Senate seat, making McNary the state's senior Senator. McNary won re-election four times, in 1924, 1930, 1936, and 1942, serving in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution....

, until his death in 1944.

Senate years

After World War IWorld War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson was the 28th President of the United States, from 1913 to 1921. A leader of the Progressive Movement, he served as President of Princeton University from 1902 to 1910, and then as the Governor of New Jersey from 1911 to 1913...

sought Senate approval of the Treaty of Versailles

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was one of the peace treaties at the end of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1919, exactly five years after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The other Central Powers on the German side of...

. Because the treaty included provisions for establishing and joining the League of Nations

League of Nations

The League of Nations was an intergovernmental organization founded as a result of the Paris Peace Conference that ended the First World War. It was the first permanent international organization whose principal mission was to maintain world peace...

, one of Wilson's Fourteen Points

Fourteen Points

The Fourteen Points was a speech given by United States President Woodrow Wilson to a joint session of Congress on January 8, 1918. The address was intended to assure the country that the Great War was being fought for a moral cause and for postwar peace in Europe...

, Republicans opposed it. Going against much of his party, McNary, part of a group of senators known as "reservationists", proposed minor changes but supported the United States entry into the League. Ultimately, the Senate never ratified the Treaty of Versailles, and the United States never joined the League of Nations.

One of the prime opponents of Wilson and the League of Nations was Senate Majority Leader Henry Cabot Lodge

Henry Cabot Lodge

Henry Cabot "Slim" Lodge was an American Republican Senator and historian from Massachusetts. He had the role of Senate Majority leader. He is best known for his positions on Meek policy, especially his battle with President Woodrow Wilson in 1919 over the Treaty of Versailles...

. After McNary demonstrated his skill in the debate over the League, Lodge took him under his wing and the two formed a longtime friendship. This friendship helped McNary secure favorable committee assignments and ushered him into the inner power circle of the Senate. Early in his career he served as chairman of the Irrigation and Reclamation of Arid Lands Committee, and as a member of the Agriculture and Forestry Committee. In 1922, President Warren G. Harding

Warren G. Harding

Warren Gamaliel Harding was the 29th President of the United States . A Republican from Ohio, Harding was an influential self-made newspaper publisher. He served in the Ohio Senate , as the 28th Lieutenant Governor of Ohio and as a U.S. Senator...

asked McNary to be the Secretary of the Interior to replace Albert B. Fall

Albert B. Fall

Albert Bacon Fall was a United States Senator from New Mexico and the Secretary of the Interior under President Warren G. Harding, infamous for his involvement in the Teapot Dome scandal.-Early life and family:...

because of Fall's involvement in the ongoing Teapot Dome scandal

Teapot Dome scandal

The Teapot Dome Scandal was a bribery incident that took place in the United States in 1922–23, during the administration of President Warren G. Harding. Secretary of the Interior Albert B. Fall leased Navy petroleum reserves at Teapot Dome and two other locations to private oil companies at low...

. McNary declined, preferring to stay in the Senate.

Democratic Party (United States)

The Democratic Party is one of two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Republican Party. The party's socially liberal and progressive platform is largely considered center-left in the U.S. political spectrum. The party has the lengthiest record of continuous...

control during the New Deal

New Deal

The New Deal was a series of economic programs implemented in the United States between 1933 and 1936. They were passed by the U.S. Congress during the first term of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The programs were Roosevelt's responses to the Great Depression, and focused on what historians call...

era. He remained minority leader for the rest of his time in office. As minority leader he "hovered most of the time on the periphery of the Republican left", and he opposed disciplining Republican senators who supported President Franklin Roosevelt. He supported many of the New Deal programs at the beginning of Roosevelt’s presidency. As World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

approached, he favored "all aid to England and France short of war". He voted to keep an arms embargo

Arms embargo

An arms embargo is an embargo that applies to weaponry. It may also include "dual use" items. An arms embargo may serve one or more purposes:# to signal disapproval of behavior by a certain actor,# to maintain neutral standing in an ongoing conflict, or...

in place, but voted for the lend-lease

Lend-Lease

Lend-Lease was the program under which the United States of America supplied the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union, China, Free France, and other Allied nations with materiel between 1941 and 1945. It was signed into law on March 11, 1941, a year and a half after the outbreak of war in Europe in...

agreement with the British in 1941 and to re-instate Selective Service in 1940 in preparation for military conscription

Conscription

Conscription is the compulsory enlistment of people in some sort of national service, most often military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and continues in some countries to the present day under various names...

of civilian men.

As early as the 1920s, McNary supported the development of federal hydroelectric power

Hydroelectricity

Hydroelectricity is the term referring to electricity generated by hydropower; the production of electrical power through the use of the gravitational force of falling or flowing water. It is the most widely used form of renewable energy...

dams, and in 1933 he introduced legislation that led to the building of the Grand Coulee

Grand Coulee Dam

Grand Coulee Dam is a gravity dam on the Columbia River in the U.S. state of Washington built to produce hydroelectric power and provide irrigation. It was constructed between 1933 and 1942, originally with two power plants. A third power station was completed in 1974 to increase its energy...

and Bonneville

Bonneville Dam

Bonneville Lock and Dam consists of several run-of-the-river dam structures that together complete a span of the Columbia River between the U.S. states of Oregon and Washington at River Mile 146.1. The dam is located east of Portland, Oregon, in the Columbia River Gorge. The primary functions of...

dams on the Columbia as public works projects. He voted in favor of the United States joining the World Court

Permanent Court of International Justice

The Permanent Court of International Justice, often called the World Court, was an international court attached to the League of Nations. Created in 1922 , the Court was initially met with a good reaction from states and academics alike, with many cases submitted to it for its first decade of...

in 1926. He favored buying more National Forest

United States National Forest

National Forest is a classification of federal lands in the United States.National Forests are largely forest and woodland areas owned by the federal government and managed by the United States Forest Service, part of the United States Department of Agriculture. Land management of these areas...

lands, re-forestation, fire protection for forests via the Clarke-McNary Act

Clarke-McNary Act

The Clarke–McNary Act of 1924 was one of several pieces of United States federal legislation which expanded the Weeks Act of 1911. It was named for Representative John D. Clarke and Senator Charles McNary....

, and farm support. Although vetoed by President Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge

John Calvin Coolidge, Jr. was the 30th President of the United States . A Republican lawyer from Vermont, Coolidge worked his way up the ladder of Massachusetts state politics, eventually becoming governor of that state...

, the McNary-Haugen Farm Relief Bill

McNary-Haugen Farm Relief Bill

The McNary-Haugen Farm Relief Act, which never became law, was a highly controversial plan in the 1920s to subsidize American agriculture by raising the domestic prices of farm products. The plan was for the government to buy the wheat, and either store it or export it at a loss. It was...

was the forerunner of the farm-related parts of the New Deal

New Deal

The New Deal was a series of economic programs implemented in the United States between 1933 and 1936. They were passed by the U.S. Congress during the first term of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The programs were Roosevelt's responses to the Great Depression, and focused on what historians call...

.

Vice presidential nomination

In 1940, he was the Republican vice presidentialVice President of the United States

The Vice President of the United States is the holder of a public office created by the United States Constitution. The Vice President, together with the President of the United States, is indirectly elected by the people, through the Electoral College, to a four-year term...

nominee, a western

Western United States

.The Western United States, commonly referred to as the American West or simply "the West," traditionally refers to the region comprising the westernmost states of the United States. Because the U.S. expanded westward after its founding, the meaning of the West has evolved over time...

farm leader chosen to balance the ticket of presidential nominee Wendell Willkie

Wendell Willkie

Wendell Lewis Willkie was a corporate lawyer in the United States and a dark horse who became the Republican Party nominee for the president in 1940. A member of the liberal wing of the GOP, he crusaded against those domestic policies of the New Deal that he thought were inefficient and...

, a pro-business leader from the east. The two men differed on many issues. Writing for Life magazine shortly before the general election in 1940, Richard L. Neuberger

Richard L. Neuberger

Richard Lewis Neuberger was a U.S. journalist, author, and politician during the middle of the 20th century. A native of Oregon, he would write for The New York Times before and after a stint in the United States Army during World War II...

said, "Whether as Vice President of the U.S. Charley McNary can keep on endorsing Government-power projects, isolation, high tariffs and huge outlays for farm relief under a President who believes in none of these things remains to be seen." McNary's acceptance speech re-iterated his support for the Tennessee Valley Authority

Tennessee Valley Authority

The Tennessee Valley Authority is a federally owned corporation in the United States created by congressional charter in May 1933 to provide navigation, flood control, electricity generation, fertilizer manufacturing, and economic development in the Tennessee Valley, a region particularly affected...

, a federally owned power-producing corporation that Willkie as "the head of a far-flung [private] utilities empire" had opposed. During the campaign, McNary promoted farming issues and criticized foreign trade agreements that he said had "closed European markets to our grain, meat, fruits and fiber." The Willkie–McNary ticket lost the Electoral College

United States Electoral College

The Electoral College consists of the electors appointed by each state who formally elect the President and Vice President of the United States. Since 1964, there have been 538 electors in each presidential election...

to President Roosevelt

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt , also known by his initials, FDR, was the 32nd President of the United States and a central figure in world events during the mid-20th century, leading the United States during a time of worldwide economic crisis and world war...

and Henry A. Wallace

Henry A. Wallace

Henry Agard Wallace was the 33rd Vice President of the United States , the Secretary of Agriculture , and the Secretary of Commerce . In the 1948 presidential election, Wallace was the nominee of the Progressive Party.-Early life:Henry A...

, 449 to 82.

Family and legacy

On December 29, 1923, McNary married for the second time, to Cornelia Woodburn Morton. He met Morton at a dinner party during World War IWorld War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, in her hometown of Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution....

Before the marriage, she worked as his private secretary. As with his first marriage, his second did not produce children, but Charles and Cornelia adopted a daughter named Charlotte in 1935.

Arboretum

An arboretum in a narrow sense is a collection of trees only. Related collections include a fruticetum , and a viticetum, a collection of vines. More commonly, today, an arboretum is a botanical garden containing living collections of woody plants intended at least partly for scientific study...

, and more than 250 acres (1 km²) of trees. Fir Cone was described as Oregon's Monticello

Monticello

Monticello is a National Historic Landmark just outside Charlottesville, Virginia, United States. It was the estate of Thomas Jefferson, the principal author of the United States Declaration of Independence, third President of the United States, and founder of the University of Virginia; it is...

by later Senator Richard L. Neuberger, as it hosted many meetings with politicians from the national stage. The farm included 110 acre (0.4451546 km²) of nut and fruit orchards, through which McNary helped establish the filbert industry in Oregon and on which he developed the Imperial prune

Prune

A prune is any of various plum cultivars, mostly Prunus domestica or European Plum, sold as fresh or dried fruit. The dried fruit is also referred to as a dried plum...

.

After complaining of headaches and suffering slurred speech beginning in early 1943, McNary went to the Bethesda, Maryland, Naval Hospital

National Naval Medical Center

The National Naval Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, USA — commonly known as the Bethesda Naval Hospital — was for decades the flagship of the United States Navy's system of medical centers. A federal institution, it conducted medical and dental research as well as providing health care for...

on November 8, 1943, where doctors diagnosed a malignant

Malignant

Malignancy is the tendency of a medical condition, especially tumors, to become progressively worse and to potentially result in death. Malignancy in cancers is characterized by anaplasia, invasiveness, and metastasis...

brain tumor. They removed it that week, and McNary was released from the hospital on December 2, but the cancer had already spread to other parts of his body. He and his family departed for Fort Lauderdale, Florida

Fort Lauderdale, Florida

Fort Lauderdale is a city in the U.S. state of Florida, on the Atlantic coast. It is the county seat of Broward County. As of the 2010 census, the city had a population of 165,521. It is a principal city of the South Florida metropolitan area, which was home to 5,564,635 people at the 2010...

, to spend the winter. He partly recovered from the surgery, but by February 24, 1944, when he was re-elected as Republican senate leader, he was comatose. Charles L. McNary died February 25, 1944, in Fort Lauderdale, and was buried in Belcrest Memorial Cemetery in Salem. He was given a state funeral, during which his body lay in state in the chamber of the Oregon House of Representatives

Oregon House of Representatives

The Oregon House of Representatives is the lower house of the Oregon Legislative Assembly. There are 60 members of the House, representing 60 districts across the state, each with a population of 57,000. The House meets at the Oregon State Capitol in Salem....

at the Oregon State Capitol

Oregon State Capitol

The Oregon State Capitol is the building housing the state legislature and the offices of the governor, secretary of state, and treasurer of the U.S. state of Oregon. It is located in the state capital, Salem. The current building, constructed from 1936 to 1938, and expanded in 1977, is the third...

in Salem.

McNary's running-mate Willkie died six months later. It was the only time both members of a major party presidential ticket

Ticket (election)

A ticket refers to a single election choice which fills more than one political office or seat. For example, in the U.S., the candidates for President and Vice President run on the same "ticket", because they are elected together on a single ballot question rather than separately.A ticket can also...

died during the term for which they sought election. At the time of his death, McNary held the record for longest-serving senator from Oregon, a record he kept until 1993 when Mark O. Hatfield surpassed his mark of 9,726 days in office.

McNary Dam

McNary Dam

McNary Dam is a 1.4-mile long concrete gravity run-of-the-river dam which spans the Columbia River. It joins Umatilla County, Oregon with Benton County, Washington, 292 miles upriver from the mouth of the Columbia at Astoria, Oregon. It is operated by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers' McNary...

on the Columbia River between Oregon and Washington is named after him, as is McNary Field

McNary Field

McNary Field , also known as Salem Municipal Airport, is a public airport located two miles southeast of the central business district of Salem, a city in Marion County, Oregon, United States, also the capital of the state. The airport is named for Senator Charles L. McNary...

, Salem's airport. McNary High School

McNary High School

McNary High School is a public high school located in Keizer, Oregon, United States. It is named for Charles L. McNary, a U.S. Senator who was from the Keizer area.-Academics:...

in Keizer

Keizer, Oregon

Keizer is a city in Marion County, Oregon, United States, along the 45th parallel. It was named for Thomas Dove and John Brooks Keizer, two pioneers who arrived in the Wagon Train of 1843, and later filed donation land claims. The population was 36,278 at the 2010 census...

and McNary Residence Hall at Oregon State University

Oregon State University

Oregon State University is a coeducational, public research university located in Corvallis, Oregon, United States. The university offers undergraduate, graduate and doctoral degrees and a multitude of research opportunities. There are more than 200 academic degree programs offered through the...

are also named in his honor.

External links

- Senate Portrait

- Salem Online History: Charles McNary

- Letter to McNary from President Hoover

- Memorial services held in the House of representatives and Senate of the United States, together with remarks presented in eulogy of Charles Linza McNary, late a senator from Oregon. Seventy-eighth Congress, second session.

- Historic images of Charles McNary from Salem Public Library

- Supreme Court Justices of Oregon

- Governors of Oregon

- Harry Lane