John C. Frémont

Encyclopedia

John Charles Frémont was an American military officer, explorer, and the first candidate of the anti-slavery Republican Party

for the office of President of the United States

. During the 1840s, that era's penny press

accorded Frémont the sobriquet The Pathfinder. It remains in use, and he is sometimes called The Great Pathfinder.

He retired from the military and moved to the new territory California

, after leading a fourth expedition which cost ten lives seeking a rail route over the mountains around the 38th parallel

in the winter of 1849.

He became one of the two U.S. Senators of the new state in 1850, and was soon bogged down with lawsuits over land claims between the dispossessions of various land owners during the Mexican-American War, and the explosion of Forty-Niners immigrating during the California Gold Rush

. He lost the 1856 presidential

election to Democrats James Buchanan

and John C. Breckenridge when Democrats warned his election would lead to civil war.

During the American Civil War

he was given command of the armies in the west but made hasty decisions (such as trying to abolish slavery without consulting the federal government), and was consequently relieved of his command (fired, then court martialed – receiving a presidential pardon).

Historians portray Frémont as controversial, impetuous, and contradictory. Some scholars regard him as a military hero of significant accomplishment, while others view him as a failure who repeatedly defeated his own best purposes. The keys to Frémont's character and personality may lie in his illegitimate birth, ambitious drive for success, self-justification, and passive-aggressive behavior.

planter Col. Thomas Whiting. The colonel died when Anne was less than a year old. Her mother married Samuel Cary, who soon exhausted most of the Whiting estate. At age 17 Anne married Major John Pryor, a wealthy Richmond resident in his early 60s. In 1810 Pryor hired Charles Fremon, a French immigrant who had fought with the Royalists during the French Revolution

, to tutor his wife. In July 1811 Pryor learned that Whiting and Fremon were having an affair. Confronted by Pryor, the couple left Richmond together on July 10, 1811, creating a scandal that shook city society. Pryor published a divorce petition in the Virginia Patriot, in which he charged that his wife had "for some time past indulged in criminal intercourse". Whiting and Fremon moved first to Norfolk, Virginia

and later settled in Savannah, Georgia

. Whiting financed the trip and purchase of a house in Savannah by selling recently inherited slaves valued at $1,900. When the Virginia House of Delegates refused Pryor’s divorce petition, it was impossible for the couple to marry. In Savannah, Whiting took in boarders while Fremon taught French and dancing. On January 21, 1813, their first child, John Charles Fremont, was born. Their son was born out of wedlock, a social handicap which he overcame later with his marriage to the daughter of a powerful U.S. senator.

In Andrew Jackson, His Life and Times, H. W. Brands wrote that Frémont added the accented "e" and the "t" to his name later in life. But in John Charles Frémont: Character as Destiny, Andre Rolle wrote that Charles Fremon was originally named Louis-René Frémont and had changed his name to Charles Fremon or Frémon upon emigrating to Virginia. Thus, John was reclaiming his father's (and family's) true French name.

, daughter of Sen. Thomas Hart Benton

from Missouri

. Benton, Democratic Party leader for more than 30 years in the Senate, championed the expansionist movement, a political cause that became known as Manifest Destiny

. The expansionists believed that the North American continent, from one end to the other, north and south, east and west, should belong to the citizens of the U.S.

They believed it was the nation's destiny to control the continent. This movement became a crusade for politicians such as Benton and his new son-in-law. Benton pushed appropriations through Congress for national surveys of the Oregon Trail

(1842), the Oregon Territory

(1844), the Great Basin

, and Sierra Mountains to California

(1845). Through his power and influence, Benton obtained for Frémont the position of leading each expedition.

from 1829 to 1831, Frémont was appointed a teacher of mathematics aboard the sloop

USS Natchez

. In July 1838 he was appointed a second lieutenant in the Corps of Topographical Engineers

and assisted and led multiple surveying

expeditions through the western territory of the United States and beyond. In 1838 and 1839 he assisted Joseph Nicollet

in exploring the lands between the Mississippi

and Missouri

rivers. In 1841 with training from Nicollet, Frémont mapped portions of the Des Moines River

.

Frémont first met frontiersman Kit Carson

on a Missouri River

steamboat in St. Louis during the summer of 1842. Frémont was preparing to lead his first expedition and was looking for a guide to take him to South Pass

. Carson offered his services, as he had spent much time in the area. The five-month journey, made with 25 men, was a success.

From 1842 to 1846 Frémont and his guide Carson led expedition parties on the Oregon Trail

and into the Sierra Nevada. During his expeditions in the Sierra Nevada, Frémont became the first American to see Lake Tahoe

. He is also credited with determining the Great Basin

as endorheic, that is, having no outlet to the sea or a river. One of Frémont's reports from an expedition inspired the Mormons

to consider Utah

for settlement. He also mapped volcanoes such as Mount St. Helens

.

Congress published Frémont's "Report and Map"; it guided thousands of overland immigrants to Oregon and California from 1845 to 1849. In 1849 Joseph Ware published his Emigrants' Guide to California (OCLC 2356459), which was largely drawn from Frémont's report, and was to guide the forty-niners through the California Gold Rush

. Frémont's report was more than a travelers' guide – it was a government publication that achieved the expansionist objectives of a nation and provided scientific and economic information concerning the potential of the trans-Mississippi West for pioneer settlement.

, on the east side of the Rocky Mountains. Upon reaching the Arkansas, however, Frémont suddenly made a hasty trail straight to California, without explanation. Arriving in the Sacramento Valley

in early 1846, he promptly sought to stir up patriotic enthusiasm among the American settlers there. He promised that if war with Mexico

started, his military force would protect the settlers. Frémont nearly provoked a battle with Gen. José Castro near Monterey

, camped at the summit of what is now named Fremont Peak

. A conflict would likely have resulted in the annihilation of Frémont's group, as Gen. Castro had the ability to organize thousands of troops. Frémont then fled Mexican-controlled California, and went north to Oregon

, making camp at Klamath Lake

.

After a May 9, 1846 Indian attack on his expedition party, Frémont retaliated by attacking a Klamath Indian fishing village named Dokdokwas the following day, although the people living there might not have been involved in the first action. The village was at the junction of the Williamson River

and Klamath Lake. On May 10, 1846, the Frémont group completely destroyed it. Afterward, Carson was nearly killed by a Klamath warrior. As Carson's gun misfired, the warrior drew to shoot a poison arrow; however, Frémont, seeing that Carson was in danger, trampled the warrior with his horse. Carson felt that he owed Frémont his life.

, he left Washington, D.C.

on May 15, 1845. He raised a group of 62 volunteers in Saint Louis. He arrived at Sutter's Fort

, on December 10, 1845.

He went to Monterrey, California, to talk with the American consul, Thomas Larkin, and Mexican major-domo Jose Castro

.

In 1846, with the arrival of USS Congress

, Frémont was appointed lieutenant colonel

of the California Battalion

, also called U.S. Mounted Rifles, which he had helped form with his survey crew and volunteers from the Bear Flag Republic, now totaling 428 men.

In June 1846, at San Rafael mission, John Frémont sent three men, one of which was Kit Carson, to confront three unarmed men debarking from a boat at Point San Pedro. Kit Carson asked John Frémont whether they should be taken prisoner. Frémont replied, "I have got no room for prisoners." They then advanced on the three and deliberately shot and killed them. One of them was an old and respected Californian, Don Jose R. Berreyesa, whose son was the Alcalde of Sonoma who had been recently imprisoned by Frémont. The two others were twin brothers and sons of Don Francisco de Haro of Yerba Buena, who had served two terms as the first and third Alcalde of Yerba Buena (later named San Francisco).

These murders were observed by Jasper O’Farrell, a famous architect and designer of San Francisco, who wrote a letter detailing it to the Los Angeles Star published on September 27, 1856. This eyewitness account, together with others, were widely published during the presidential election of 1856, which featured John Frémont as the first anti-slavery Republican nominee versus Democrat James Buchanan

.

It is widely speculated that this incident, together with other military blunders, sunk Frémont’s political aspirations.

In late 1846 Frémont, acting under orders from Commodore

Robert F. Stockton

, led a military expedition of 300 men to capture Santa Barbara, California

, during the Mexican-American War.

Frémont led his unit over the Santa Ynez Mountains

at San Marcos Pass

in a rainstorm on the night of December 24, 1846.

In spite of losing many of his horses, mules and cannons, which slid down the muddy slopes during the rainy night, his men regrouped in the foothills the next morning, and captured the presidio without bloodshed, thereby capturing the town.

A few days later Frémont led his men southeast toward Los Angeles, accepting the surrender of the leader Andres Pico

and signing the Treaty of Cahuenga

on January 13, 1847, which terminated the war in upper California.

On January 16, 1847, Commodore Stockton appointed Frémont military governor of California following the Treaty of Cahuenga

. However, U.S. Army Brig. Gen. Stephen Watts Kearny, who outranked Frémont (and who arguably had the same rank as Stockton, one star), said he had orders from the U.S. president and secretary of war

to serve as governor. He asked Frémont to give up the governorship, which the latter stubbornly refused to do for a time. Kearny gave Frémont several opportunities to change his position. When they arrived at Fort Leavenworth

in August 1847, Kearny arrested Frémont and brought him to Washington, for court martial. Frémont was convicted of mutiny

, disobedience of a superior officer and military misconduct.

While approving the court's decision, Pres. James K. Polk

quickly commuted his sentence of dishonorable discharge due to his services. Frémont resigned his commission and settled in California. In 1847 he purchased the Rancho Las Mariposas

land grant in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada mountains near Yosemite

.

In 1848 Frémont and his father-in-law Sen. Benton developed a plan to advance their vision of Manifest Destiny, as well as restore Frémont's honor after his court martial. With a keen interest in the potential of railroads, Sen. Benton had sought support from the Senate for a railroad connecting St. Louis to San Francisco along the 38th parallel, the latitude which both cities approximately share. After Benton failed to secure federal funding, Frémont secured private funding. In October 1848 he embarked with 35 men up the Missouri

In 1848 Frémont and his father-in-law Sen. Benton developed a plan to advance their vision of Manifest Destiny, as well as restore Frémont's honor after his court martial. With a keen interest in the potential of railroads, Sen. Benton had sought support from the Senate for a railroad connecting St. Louis to San Francisco along the 38th parallel, the latitude which both cities approximately share. After Benton failed to secure federal funding, Frémont secured private funding. In October 1848 he embarked with 35 men up the Missouri

, Kansas

and Arkansas

rivers to explore the terrain.

On his party's reaching Bent's Fort, he was strongly advised by most of the trappers against continuing the journey. Already a foot of snow was on the ground at Bent's Fort, and the winter in the mountains promised to be especially snowy. Part of Frémont's purpose was to demonstrate that a 38th parallel railroad would be practical year-round. At Bent's Fort he secured "Uncle Dick" Wootton as guide, and at what is now Pueblo, Colorado

, he hired the eccentric "Old Bill" Williams

and moved on.

Had Frémont continued up the Arkansas, he might have succeeded. On November 25 at what is now Florence, Colorado

, he turned sharply south. By the time his party crossed the Sangre de Cristo Range

via Mocha Pass, they had already experienced days of bitter cold, blinding snow and difficult travel. Some of the party, including the guide Wootton, had already turned back, concluding further travel would be impossible. Although the passes through the Sangre de Cristo had proven too steep for a railroad, Frémont pressed on. From this point the party might still have succeeded had they gone up the Rio Grande

to its source, or gone by a more northerly route, but the route they took brought them to the very top of Mesa Mountain. By December 12, on Boot Mountain it took ninety minutes to progress three hundred yards. Mules began dying and by 20 December only 59 animals remained alive. It was not until December 22 that Frémont acknowledged the party needed to regroup and be resupplied. They began to make their way to Taos

, New Mexico

. By the time the last surviving member of the expedition made it to Taos on February 12, 1849, 10 of the party were dead. Except for the efforts of member Alexis Godey, another 15 would have been lost. After recuperating in Taos, Frémont and only a few of the men left for California via an established southern trade route.

from California, serving only a few months, from 1850 to 1851. He had previously served as Military Governor of California in 1847.

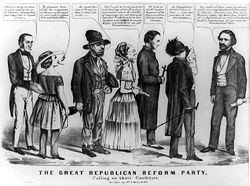

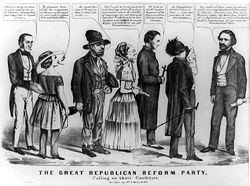

Frémont was the first presidential candidate of the new Republican Party in 1856. It used the slogan "Free Soil, Free Men, and Frémont" to crusade for free farms (homesteads) and against the Slave Power

. As was typical in presidential campaigns, the candidates stayed at home and said little. The Democrats meanwhile counter-crusaded against the Republicans, warning that a victory by Frémont would bring civil war. They also raised a host of issues, alleging Frémont was a Catholic and had a poor military record. Frémont's powerful father-in-law, Senator Benton, praised Frémont but announced his support for the Democratic candidate James Buchanan

.

At the time of his campaign he lived in Staten Island

, New York

. The campaign was headquartered near his home in St. George. He placed second to James Buchanan

in a three-way election

; he did not carry the state of California.

He later served as Governor of the Arizona Territory

He later served as Governor of the Arizona Territory

for several years, though he spent little time in the territory; he was asked to resume his duties or resign, and chose resignation.

, including a controversial term as commander of the Army's Department of the West

from May to November 1861. Frémont replaced William S. Harney

, who had negotiated the Harney-Price Truce, which permitted Missouri

to remain neutral in the conflict as long as it did not send men or supplies to either side.

Frémont ordered his Gen. Nathaniel Lyon

to formally bring Missouri into the Union

cause. Lyon had been named the temporary commander of the Department of the West, before Frémont ultimately replaced Lyon. Lyon, in a series of battles, evicted Gov. Claiborne Jackson and installed a pro-Union government. After Lyon was killed in the Battle of Wilson's Creek

in August, Frémont imposed martial law

in the state, confiscating secessionists' private property and emancipating slaves

.

Pres. Abraham Lincoln

Pres. Abraham Lincoln

, fearing the order would tip Missouri (and other slave states in Union control) to the southern cause, asked Frémont to revise the order. Frémont refused to do so, and sent his wife to plead the case. Lincoln responded by publicly revoking the proclamation and relieving Frémont of command on November 2, 1861, simultaneous to a War Department report detailing Frémont's iniquities as a major general. In March 1862 he was placed in command of the Mountain Department of Virginia

, Tennessee

and Kentucky

.

Early in June 1862 Frémont pursued the Confederate Gen. Stonewall Jackson

for eight days, finally engaging him at Battle of Cross Keys

on June 8. Jackson slipped away after the battle, saving his army.

When the Army of Virginia

was created June 26, to include Gen. Frémont's corps, with John Pope

in command, Frémont declined to serve on the grounds that he was senior to Pope and for personal reasons. He then went to New York where he remained throughout the war, expecting a command, but none was given to him.

for president, who won the presidency and then ran for reelection in 1864. The Radical Republicans, a group of hard-line abolitionists

, were upset with Lincoln's positions on the issues of slavery and post-war reconciliation with the southern states. On May 31, 1864, they nominated Frémont for president. This fissure in the Republican Party divided the party into two factions: the anti-Lincoln Radical Republicans, who nominated Frémont, and the pro-Lincoln Republicans. Frémont abandoned his political campaign in September 1864, after he brokered a political deal in which Lincoln removed Postmaster General

Montgomery Blair

from office.

took possession of the Pacific Railroad

in February 1866, when the company defaulted in its interest payment. In June 1866 the state, at private sale, sold the road to Frémont. Frémont reorganized the assets of the Pacific Railroad as the Southwest Pacific Railroad in August 1866. In less than a year (June 1867), the railroad was repossessed by the state of Missouri after Frémont was unable to pay the second installment on his purchase.

From 1878 to 1881 Frémont was governor of the Arizona Territory

. Destitute, the family depended on the publication earnings of his wife Jessie.

Frémont lived on Staten Island in retirement. He died in New York City

in 1890 of peritonitis

, a forgotten man. He was buried in Rockland Cemetery, Sparkill

, New York

.

by a European American. The genus of the California Flannelbush (Fremontodendron californicum) is named for him, as are the species names of many other plants, including the chaff bush eytelia (Amphipappus fremontii), Western rosinweed (Calycadenia fremontii

), pincushion flower (Chaenactis fremontii

), goosefoot (Chenopodium fremontii

), silk tassel (Garrya fremontii

), moss gentian (Gentiana fremontii), vernal pool goldfields (Lasthenia fremontii

), tidytips (Layia fremontii

), desert pepperweed (Lepidium fremontii

), desert boxthorn (Lycium fremontii

), barberry (Mahonia fremontii

), bush mallow (Malacothamnus fremontii

), monkeyflower (Mimulus fremontii

), phacelia (Phacelia fremontii

), desert combleaf (Polyctenium fremontii

), cottonwood tree (Populus fremontii

), desert apricot (Prunus fremontii

), indigo bush (Psorothamnus fremontii

), mountain ragwort (Senecio fremontii

), yellowray gold (Syntrichopappus fremontii

), and chaparral death camas (Toxicoscordion fremontii).

The city of Elizabeth, South Australia

(now a part of the city of Playford

) named a local park and high school Fremont in recognition of the sister city relationship it had with Fremont, California

. The high school has since merged with Elizabeth High School, so the Pathfinder's legacy is carried by Fremont-Elizabeth City High School

.

The "largest and most expensive 'trophy'" in college football is a replica of a cannon "that accompanied Captain John C. Frémont on his expedition through Oregon, Nevada and California in 1843–44". The annual game between the University of Nevada, Reno

and the University of Nevada, Las Vegas

is for possession of the Fremont Cannon

.

A barbershop

chorus in Fremont, Nebraska, is named The Fremont Pathfinders. The Fremont Pathfinders Artillery Battery is an American Civil War reenactment

group from the same community.

Fremont Street

in Las Vegas, Nevada

, is named in his honor, as are streets in Minneapolis, Minnesota

; Kiel, Wisconsin

; Manhattan, Kansas

; Portland, Oregon

; Grant City, Staten Island, New York

; Tempe, Arizona

; and Tucson, Arizona

, as well as several cities in California: Fremont

, Monterey

, Seaside

, Stockton

, San Mateo

, San Francisco

, and Santa Clara

.

Portland, Oregon also has several other locations named after Frémont, such as Fremont Bridge. Other places named for him include John C. Fremont Senior High School in Los Angeles

, Fremont High School in Plain City, Utah, and Fremont Senior High School

in Oakland

, and the John C. Fremont Branch Library located on Melrose Avenue

in Los Angeles

. Elementary schools in Glendale, California

; Modesto, California

; Long Beach, California

; and Carson City, Nevada

bear his name, as do junior high or middle schools in Mesa, Arizona

; Pomona, California

; Las Vegas, Nevada

; Roseburg, Oregon

; and Oxnard, California

. Fremont High School

in Sunnyvale, California

, is named for the explorer and its annual yearbook is called The Pathfinder. In addition, the Fremont Hospital in Yuba City, California

,and the John C. Fremont Hospital, in Mariposa, California

, (where Frémont and his wife lived and prospered during the Gold Rush

) are named for him. There is also a John C. Fremont Library in Florence, Colorado

.

.

History of the United States Republican Party

The United States Republican Party is the second oldest currently existing political party in the United States after its great rival, the Democratic Party. It emerged in 1854 to combat the Kansas Nebraska Act which threatened to extend slavery into the territories, and to promote more vigorous...

for the office of President of the United States

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

. During the 1840s, that era's penny press

Penny press

Penny press newspapers were cheap, tabloid-style papers produced in the middle of the 19th century.- History :As the East Coast's middle and working classes grew, so did the new public’s desire for news. Penny papers emerged as a cheap source with coverage of crime, tragedy, adventure, and gossip...

accorded Frémont the sobriquet The Pathfinder. It remains in use, and he is sometimes called The Great Pathfinder.

He retired from the military and moved to the new territory California

California

California is a state located on the West Coast of the United States. It is by far the most populous U.S. state, and the third-largest by land area...

, after leading a fourth expedition which cost ten lives seeking a rail route over the mountains around the 38th parallel

38th parallel north

The 38th parallel north is a circle of latitude that is 38 degrees north of the Earth's equatorial plane. It crosses Europe, the Mediterranean Sea, Asia, the Pacific Ocean, North America, and the Atlantic Ocean...

in the winter of 1849.

He became one of the two U.S. Senators of the new state in 1850, and was soon bogged down with lawsuits over land claims between the dispossessions of various land owners during the Mexican-American War, and the explosion of Forty-Niners immigrating during the California Gold Rush

California Gold Rush

The California Gold Rush began on January 24, 1848, when gold was found by James W. Marshall at Sutter's Mill in Coloma, California. The first to hear confirmed information of the gold rush were the people in Oregon, the Sandwich Islands , and Latin America, who were the first to start flocking to...

. He lost the 1856 presidential

United States presidential election, 1856

The United States presidential election of 1856 was an unusually heated contest that led to the election of James Buchanan, the ambassador to the United Kingdom. Republican candidate John C. Frémont condemned the Kansas–Nebraska Act and crusaded against the expansion of slavery, while Democrat...

election to Democrats James Buchanan

James Buchanan

James Buchanan, Jr. was the 15th President of the United States . He is the only president from Pennsylvania, the only president who remained a lifelong bachelor and the last to be born in the 18th century....

and John C. Breckenridge when Democrats warned his election would lead to civil war.

During the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

he was given command of the armies in the west but made hasty decisions (such as trying to abolish slavery without consulting the federal government), and was consequently relieved of his command (fired, then court martialed – receiving a presidential pardon).

Historians portray Frémont as controversial, impetuous, and contradictory. Some scholars regard him as a military hero of significant accomplishment, while others view him as a failure who repeatedly defeated his own best purposes. The keys to Frémont's character and personality may lie in his illegitimate birth, ambitious drive for success, self-justification, and passive-aggressive behavior.

Parents

Frémont's mother, Anne Beverley Whiting, was the youngest daughter of socially prominent VirginiaVirginia

The Commonwealth of Virginia , is a U.S. state on the Atlantic Coast of the Southern United States. Virginia is nicknamed the "Old Dominion" and sometimes the "Mother of Presidents" after the eight U.S. presidents born there...

planter Col. Thomas Whiting. The colonel died when Anne was less than a year old. Her mother married Samuel Cary, who soon exhausted most of the Whiting estate. At age 17 Anne married Major John Pryor, a wealthy Richmond resident in his early 60s. In 1810 Pryor hired Charles Fremon, a French immigrant who had fought with the Royalists during the French Revolution

French Revolution

The French Revolution , sometimes distinguished as the 'Great French Revolution' , was a period of radical social and political upheaval in France and Europe. The absolute monarchy that had ruled France for centuries collapsed in three years...

, to tutor his wife. In July 1811 Pryor learned that Whiting and Fremon were having an affair. Confronted by Pryor, the couple left Richmond together on July 10, 1811, creating a scandal that shook city society. Pryor published a divorce petition in the Virginia Patriot, in which he charged that his wife had "for some time past indulged in criminal intercourse". Whiting and Fremon moved first to Norfolk, Virginia

Norfolk, Virginia

Norfolk is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. With a population of 242,803 as of the 2010 Census, it is Virginia's second-largest city behind neighboring Virginia Beach....

and later settled in Savannah, Georgia

Savannah, Georgia

Savannah is the largest city and the county seat of Chatham County, in the U.S. state of Georgia. Established in 1733, the city of Savannah was the colonial capital of the Province of Georgia and later the first state capital of Georgia. Today Savannah is an industrial center and an important...

. Whiting financed the trip and purchase of a house in Savannah by selling recently inherited slaves valued at $1,900. When the Virginia House of Delegates refused Pryor’s divorce petition, it was impossible for the couple to marry. In Savannah, Whiting took in boarders while Fremon taught French and dancing. On January 21, 1813, their first child, John Charles Fremont, was born. Their son was born out of wedlock, a social handicap which he overcame later with his marriage to the daughter of a powerful U.S. senator.

In Andrew Jackson, His Life and Times, H. W. Brands wrote that Frémont added the accented "e" and the "t" to his name later in life. But in John Charles Frémont: Character as Destiny, Andre Rolle wrote that Charles Fremon was originally named Louis-René Frémont and had changed his name to Charles Fremon or Frémon upon emigrating to Virginia. Thus, John was reclaiming his father's (and family's) true French name.

Marriage

In 1841 John C. Frémont married Jessie BentonJessie Benton Frémont

Jessie Ann Benton Frémont was an American writer and political activist.Notably remembered for being the daughter of Missouri Senator Thomas Hart Benton and the wife of military officer, explorer and politician, John C. Frémont, she wrote many stories that were printed in popular magazines of the...

, daughter of Sen. Thomas Hart Benton

Thomas Hart Benton (senator)

Thomas Hart Benton , nicknamed "Old Bullion", was a U.S. Senator from Missouri and a staunch advocate of westward expansion of the United States. He served in the Senate from 1821 to 1851, becoming the first member of that body to serve five terms...

from Missouri

Missouri

Missouri is a US state located in the Midwestern United States, bordered by Iowa, Illinois, Kentucky, Tennessee, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Kansas and Nebraska. With a 2010 population of 5,988,927, Missouri is the 18th most populous state in the nation and the fifth most populous in the Midwest. It...

. Benton, Democratic Party leader for more than 30 years in the Senate, championed the expansionist movement, a political cause that became known as Manifest Destiny

Manifest Destiny

Manifest Destiny was the 19th century American belief that the United States was destined to expand across the continent. It was used by Democrat-Republicans in the 1840s to justify the war with Mexico; the concept was denounced by Whigs, and fell into disuse after the mid-19th century.Advocates of...

. The expansionists believed that the North American continent, from one end to the other, north and south, east and west, should belong to the citizens of the U.S.

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

They believed it was the nation's destiny to control the continent. This movement became a crusade for politicians such as Benton and his new son-in-law. Benton pushed appropriations through Congress for national surveys of the Oregon Trail

Oregon Trail

The Oregon Trail is a historic east-west wagon route that connected the Missouri River to valleys in Oregon and locations in between.After 1840 steam-powered riverboats and steamboats traversing up and down the Ohio, Mississippi and Missouri rivers sped settlement and development in the flat...

(1842), the Oregon Territory

Oregon Territory

The Territory of Oregon was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from August 14, 1848, until February 14, 1859, when the southwestern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Oregon. Originally claimed by several countries , the region was...

(1844), the Great Basin

Great Basin

The Great Basin is the largest area of contiguous endorheic watersheds in North America and is noted for its arid conditions and Basin and Range topography that varies from the North American low point at Badwater Basin to the highest point of the contiguous United States, less than away at the...

, and Sierra Mountains to California

California

California is a state located on the West Coast of the United States. It is by far the most populous U.S. state, and the third-largest by land area...

(1845). Through his power and influence, Benton obtained for Frémont the position of leading each expedition.

Early expeditions

After attending the College of CharlestonCollege of Charleston

The College of Charleston is a public, sea-grant and space-grant university located in historic downtown Charleston, South Carolina, United States...

from 1829 to 1831, Frémont was appointed a teacher of mathematics aboard the sloop

Sloop

A sloop is a sail boat with a fore-and-aft rig and a single mast farther forward than the mast of a cutter....

USS Natchez

USS Natchez (1827)

The first USS Natchez was a sloop-of-war in the United States Navy.Natchez was built by Norfolk Navy Yard in 1827, commanded by Commander George Budd, departed Hampton Roads on 26 July 1827 for the Caribbean...

. In July 1838 he was appointed a second lieutenant in the Corps of Topographical Engineers

Corps of Topographical Engineers

The U.S. Army Corps of Topographical Engineers, was separately authorized on 4 July 1838, consisted only of officers, and was used for mapping and the design and construction of federal civil works such as lighthouses and other coastal fortifications and navigational routes. It included such...

and assisted and led multiple surveying

Surveying

See Also: Public Land Survey SystemSurveying or land surveying is the technique, profession, and science of accurately determining the terrestrial or three-dimensional position of points and the distances and angles between them...

expeditions through the western territory of the United States and beyond. In 1838 and 1839 he assisted Joseph Nicollet

Joseph Nicollet

Joseph Nicolas Nicollet , also known as Jean-Nicolas Nicollet, was a French geographer and mathematician known for mapping the Upper Mississippi River basin during the 1830s....

in exploring the lands between the Mississippi

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the largest river system in North America. Flowing entirely in the United States, this river rises in western Minnesota and meanders slowly southwards for to the Mississippi River Delta at the Gulf of Mexico. With its many tributaries, the Mississippi's watershed drains...

and Missouri

Missouri River

The Missouri River flows through the central United States, and is a tributary of the Mississippi River. It is the longest river in North America and drains the third largest area, though only the thirteenth largest by discharge. The Missouri's watershed encompasses most of the American Great...

rivers. In 1841 with training from Nicollet, Frémont mapped portions of the Des Moines River

Des Moines River

The Des Moines River is a tributary river of the Mississippi River, approximately long to its farther headwaters, in the upper Midwestern United States...

.

Frémont first met frontiersman Kit Carson

Kit Carson

Christopher Houston "Kit" Carson was an American frontiersman and Indian fighter. Carson left home in rural present-day Missouri at age 16 and became a Mountain man and trapper in the West. Carson explored the west to California, and north through the Rocky Mountains. He lived among and married...

on a Missouri River

Missouri River

The Missouri River flows through the central United States, and is a tributary of the Mississippi River. It is the longest river in North America and drains the third largest area, though only the thirteenth largest by discharge. The Missouri's watershed encompasses most of the American Great...

steamboat in St. Louis during the summer of 1842. Frémont was preparing to lead his first expedition and was looking for a guide to take him to South Pass

South Pass

South Pass is two mountain passes on the Continental Divide in the Rocky Mountains in southwestern Wyoming. The passes are located in a broad low region, 35 miles broad, between the Wind River Range to the north and the Oregon Buttes and Great Divide Basin to the south, in southwestern Fremont...

. Carson offered his services, as he had spent much time in the area. The five-month journey, made with 25 men, was a success.

From 1842 to 1846 Frémont and his guide Carson led expedition parties on the Oregon Trail

Oregon Trail

The Oregon Trail is a historic east-west wagon route that connected the Missouri River to valleys in Oregon and locations in between.After 1840 steam-powered riverboats and steamboats traversing up and down the Ohio, Mississippi and Missouri rivers sped settlement and development in the flat...

and into the Sierra Nevada. During his expeditions in the Sierra Nevada, Frémont became the first American to see Lake Tahoe

Lake Tahoe

Lake Tahoe is a large freshwater lake in the Sierra Nevada of the United States. At a surface elevation of , it is located along the border between California and Nevada, west of Carson City. Lake Tahoe is the largest alpine lake in North America. Its depth is , making it the USA's second-deepest...

. He is also credited with determining the Great Basin

Great Basin

The Great Basin is the largest area of contiguous endorheic watersheds in North America and is noted for its arid conditions and Basin and Range topography that varies from the North American low point at Badwater Basin to the highest point of the contiguous United States, less than away at the...

as endorheic, that is, having no outlet to the sea or a river. One of Frémont's reports from an expedition inspired the Mormons

Mormons

The Mormons are a religious and cultural group related to Mormonism, a religion started by Joseph Smith during the American Second Great Awakening. A vast majority of Mormons are members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints while a minority are members of other independent churches....

to consider Utah

Utah

Utah is a state in the Western United States. It was the 45th state to join the Union, on January 4, 1896. Approximately 80% of Utah's 2,763,885 people live along the Wasatch Front, centering on Salt Lake City. This leaves vast expanses of the state nearly uninhabited, making the population the...

for settlement. He also mapped volcanoes such as Mount St. Helens

Mount St. Helens

Mount St. Helens is an active stratovolcano located in Skamania County, Washington, in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is south of Seattle, Washington and northeast of Portland, Oregon. Mount St. Helens takes its English name from the British diplomat Lord St Helens, a...

.

Congress published Frémont's "Report and Map"; it guided thousands of overland immigrants to Oregon and California from 1845 to 1849. In 1849 Joseph Ware published his Emigrants' Guide to California (OCLC 2356459), which was largely drawn from Frémont's report, and was to guide the forty-niners through the California Gold Rush

California Gold Rush

The California Gold Rush began on January 24, 1848, when gold was found by James W. Marshall at Sutter's Mill in Coloma, California. The first to hear confirmed information of the gold rush were the people in Oregon, the Sandwich Islands , and Latin America, who were the first to start flocking to...

. Frémont's report was more than a travelers' guide – it was a government publication that achieved the expansionist objectives of a nation and provided scientific and economic information concerning the potential of the trans-Mississippi West for pioneer settlement.

Third expedition

On June 1, 1845, John Frémont and 55 men left St. Louis, with Carson as guide, on the third expedition. The stated goal was to locate the source of the Arkansas RiverArkansas River

The Arkansas River is a major tributary of the Mississippi River. The Arkansas generally flows to the east and southeast as it traverses the U.S. states of Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas. The river's initial basin starts in the Western United States in Colorado, specifically the Arkansas...

, on the east side of the Rocky Mountains. Upon reaching the Arkansas, however, Frémont suddenly made a hasty trail straight to California, without explanation. Arriving in the Sacramento Valley

Sacramento Valley

The Sacramento Valley is the portion of the California Central Valley that lies to the north of the San Joaquin-Sacramento Delta in the U.S. state of California. It encompasses all or parts of ten counties.-Geography:...

in early 1846, he promptly sought to stir up patriotic enthusiasm among the American settlers there. He promised that if war with Mexico

Mexico

The United Mexican States , commonly known as Mexico , is a federal constitutional republic in North America. It is bordered on the north by the United States; on the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; on the southeast by Guatemala, Belize, and the Caribbean Sea; and on the east by the Gulf of...

started, his military force would protect the settlers. Frémont nearly provoked a battle with Gen. José Castro near Monterey

Monterey, California

The City of Monterey in Monterey County is located on Monterey Bay along the Pacific coast in Central California. Monterey lies at an elevation of 26 feet above sea level. As of the 2010 census, the city population was 27,810. Monterey is of historical importance because it was the capital of...

, camped at the summit of what is now named Fremont Peak

Fremont Peak (California)

Fremont Peak is a summit in the Gabilan Range, one of the mountain ranges paralleling California's central coast. The peak affords clear views of the Salinas Valley and Monterey Bay. It is located on Rocky Ridge, northeast of Salinas, California....

. A conflict would likely have resulted in the annihilation of Frémont's group, as Gen. Castro had the ability to organize thousands of troops. Frémont then fled Mexican-controlled California, and went north to Oregon

Oregon

Oregon is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is located on the Pacific coast, with Washington to the north, California to the south, Nevada on the southeast and Idaho to the east. The Columbia and Snake rivers delineate much of Oregon's northern and eastern...

, making camp at Klamath Lake

Upper Klamath Lake

Upper Klamath Lake is a large, shallow freshwater lake east of the Cascade Range in south central Oregon in the United States. The largest freshwater body in Oregon, it is approximately 20 mi long and 8 mi wide and extends northwest from the city of Klamath Falls...

.

After a May 9, 1846 Indian attack on his expedition party, Frémont retaliated by attacking a Klamath Indian fishing village named Dokdokwas the following day, although the people living there might not have been involved in the first action. The village was at the junction of the Williamson River

Williamson River (Oregon)

The Williamson River of south-central Oregon in the United States is about long. It drains about east of the Cascade Range. Together with its principal tributary, the Sprague River, it provides over half the inflow to Upper Klamath Lake, the largest freshwater lake in Oregon...

and Klamath Lake. On May 10, 1846, the Frémont group completely destroyed it. Afterward, Carson was nearly killed by a Klamath warrior. As Carson's gun misfired, the warrior drew to shoot a poison arrow; however, Frémont, seeing that Carson was in danger, trampled the warrior with his horse. Carson felt that he owed Frémont his life.

Mexican-American War

After meeting with President James K. PolkJames K. Polk

James Knox Polk was the 11th President of the United States . Polk was born in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina. He later lived in and represented Tennessee. A Democrat, Polk served as the 17th Speaker of the House of Representatives and the 12th Governor of Tennessee...

, he left Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution....

on May 15, 1845. He raised a group of 62 volunteers in Saint Louis. He arrived at Sutter's Fort

Sutter's Fort

Sutter's Fort State Historic Park is a state-protected park in Sacramento, California which includes Sutter's Fort and the California State Indian Museum. Begun in 1839 and originally called "New Helvetia" by its builder, John Sutter, the fort was a 19th century agricultural and trade colony in...

, on December 10, 1845.

He went to Monterrey, California, to talk with the American consul, Thomas Larkin, and Mexican major-domo Jose Castro

Jose Castro

José Castro may refer to:*José Ribeiro e Castro , Portuguese politician*José Antonio Castro , 19th century Mexican governor of Alta California*José Castro , professional baseball coach...

.

In 1846, with the arrival of USS Congress

USS Congress (1841)

USS Congress — the fourth United States Navy ship to carry that name — was a sailing frigate, like her predecessor, .Congress served with distinction in the Mediterranean, South Atlantic Ocean, and in the Pacific Ocean...

, Frémont was appointed lieutenant colonel

Lieutenant Colonel (United States)

In the United States Army, United States Air Force, and United States Marine Corps, a lieutenant colonel is a field grade military officer rank just above the rank of major and just below the rank of colonel. It is equivalent to the naval rank of commander in the other uniformed services.The pay...

of the California Battalion

California Battalion

The first California Volunteer Militia was commonly called the California Battalion was organized by John C. Fremont during the Mexican-American War in Alta California, present day California, United States.-Formation:...

, also called U.S. Mounted Rifles, which he had helped form with his survey crew and volunteers from the Bear Flag Republic, now totaling 428 men.

In June 1846, at San Rafael mission, John Frémont sent three men, one of which was Kit Carson, to confront three unarmed men debarking from a boat at Point San Pedro. Kit Carson asked John Frémont whether they should be taken prisoner. Frémont replied, "I have got no room for prisoners." They then advanced on the three and deliberately shot and killed them. One of them was an old and respected Californian, Don Jose R. Berreyesa, whose son was the Alcalde of Sonoma who had been recently imprisoned by Frémont. The two others were twin brothers and sons of Don Francisco de Haro of Yerba Buena, who had served two terms as the first and third Alcalde of Yerba Buena (later named San Francisco).

These murders were observed by Jasper O’Farrell, a famous architect and designer of San Francisco, who wrote a letter detailing it to the Los Angeles Star published on September 27, 1856. This eyewitness account, together with others, were widely published during the presidential election of 1856, which featured John Frémont as the first anti-slavery Republican nominee versus Democrat James Buchanan

James Buchanan

James Buchanan, Jr. was the 15th President of the United States . He is the only president from Pennsylvania, the only president who remained a lifelong bachelor and the last to be born in the 18th century....

.

It is widely speculated that this incident, together with other military blunders, sunk Frémont’s political aspirations.

In late 1846 Frémont, acting under orders from Commodore

Commodore (rank)

Commodore is a military rank used in many navies that is superior to a navy captain, but below a rear admiral. Non-English-speaking nations often use the rank of flotilla admiral or counter admiral as an equivalent .It is often regarded as a one-star rank with a NATO code of OF-6, but is not always...

Robert F. Stockton

Robert F. Stockton

Robert Field Stockton was a United States naval commodore, notable in the capture of California during the Mexican-American War. He was a naval innovator and an early advocate for a propeller-driven, steam-powered navy. Stockton was from a notable political family and also served as a U.S...

, led a military expedition of 300 men to capture Santa Barbara, California

History of Santa Barbara, California

The history of Santa Barbara, California, begins approximately 13,000 years ago with the arrival of the first Native Americans. The Spanish came in the 18th century to occupy and Christianize the area, which became part of Mexico following the Mexican War of Independence...

, during the Mexican-American War.

Frémont led his unit over the Santa Ynez Mountains

Santa Ynez Mountains

The Santa Ynez Mountains are a portion of the Transverse Ranges, part of the Pacific Coast Ranges of the west coast of North America, and are one of the northernmost mountain ranges in Southern California.-Geography:...

at San Marcos Pass

San Marcos Pass

San Marcos Pass is a mountain pass in the Santa Ynez Mountains in California.It is traversed by State Route 154. The pass connects Los Olivos and the Santa Ynez Valley with Santa Barbara, California...

in a rainstorm on the night of December 24, 1846.

In spite of losing many of his horses, mules and cannons, which slid down the muddy slopes during the rainy night, his men regrouped in the foothills the next morning, and captured the presidio without bloodshed, thereby capturing the town.

A few days later Frémont led his men southeast toward Los Angeles, accepting the surrender of the leader Andres Pico

Andrés Pico

Andrés Pico was a Californio who became a successful rancher, served as a military commander during the Mexican-American War; and was elected to the state assembly and senate after California became a state, when he was also commissioned as a brigadier general in the state militia.-Early...

and signing the Treaty of Cahuenga

Treaty of Cahuenga

The Treaty of Cahuenga, also called the "Capitulation of Cahuenga," ended the fighting of the Mexican-American War in Alta California in 1847. It was not a formal treaty between nations but an informal agreement between rival military forces in which the Californios gave up fighting...

on January 13, 1847, which terminated the war in upper California.

On January 16, 1847, Commodore Stockton appointed Frémont military governor of California following the Treaty of Cahuenga

Treaty of Cahuenga

The Treaty of Cahuenga, also called the "Capitulation of Cahuenga," ended the fighting of the Mexican-American War in Alta California in 1847. It was not a formal treaty between nations but an informal agreement between rival military forces in which the Californios gave up fighting...

. However, U.S. Army Brig. Gen. Stephen Watts Kearny, who outranked Frémont (and who arguably had the same rank as Stockton, one star), said he had orders from the U.S. president and secretary of war

United States Secretary of War

The Secretary of War was a member of the United States President's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War," was appointed to serve the Congress of the Confederation under the Articles of Confederation...

to serve as governor. He asked Frémont to give up the governorship, which the latter stubbornly refused to do for a time. Kearny gave Frémont several opportunities to change his position. When they arrived at Fort Leavenworth

Fort Leavenworth

Fort Leavenworth is a United States Army facility located in Leavenworth County, Kansas, immediately north of the city of Leavenworth in the upper northeast portion of the state. It is the oldest active United States Army post west of Washington, D.C. and has been in operation for over 180 years...

in August 1847, Kearny arrested Frémont and brought him to Washington, for court martial. Frémont was convicted of mutiny

Mutiny

Mutiny is a conspiracy among members of a group of similarly situated individuals to openly oppose, change or overthrow an authority to which they are subject...

, disobedience of a superior officer and military misconduct.

While approving the court's decision, Pres. James K. Polk

James K. Polk

James Knox Polk was the 11th President of the United States . Polk was born in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina. He later lived in and represented Tennessee. A Democrat, Polk served as the 17th Speaker of the House of Representatives and the 12th Governor of Tennessee...

quickly commuted his sentence of dishonorable discharge due to his services. Frémont resigned his commission and settled in California. In 1847 he purchased the Rancho Las Mariposas

Rancho Las Mariposas

Rancho Las Mariposas was a Mexican land grant in present day Mariposa County, California given in 1844 by Governor Manuel Micheltorena to Juan Bautista Alvarado. The grant takes its name from Mariposa Creek, which was named for the butterflies in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada mountains...

land grant in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada mountains near Yosemite

Yosemite National Park

Yosemite National Park is a United States National Park spanning eastern portions of Tuolumne, Mariposa and Madera counties in east central California, United States. The park covers an area of and reaches across the western slopes of the Sierra Nevada mountain chain...

.

Fourth expedition

Missouri River

The Missouri River flows through the central United States, and is a tributary of the Mississippi River. It is the longest river in North America and drains the third largest area, though only the thirteenth largest by discharge. The Missouri's watershed encompasses most of the American Great...

, Kansas

Kansas River

The Kansas River is a river in northeastern Kansas in the United States. It is the southwestern-most part of the Missouri River drainage, which is in turn the northwestern-most portion of the extensive Mississippi River drainage. Its name come from the Kanza people who once inhabited the area...

and Arkansas

Arkansas River

The Arkansas River is a major tributary of the Mississippi River. The Arkansas generally flows to the east and southeast as it traverses the U.S. states of Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas. The river's initial basin starts in the Western United States in Colorado, specifically the Arkansas...

rivers to explore the terrain.

On his party's reaching Bent's Fort, he was strongly advised by most of the trappers against continuing the journey. Already a foot of snow was on the ground at Bent's Fort, and the winter in the mountains promised to be especially snowy. Part of Frémont's purpose was to demonstrate that a 38th parallel railroad would be practical year-round. At Bent's Fort he secured "Uncle Dick" Wootton as guide, and at what is now Pueblo, Colorado

Pueblo, Colorado

Pueblo is a Home Rule Municipality that is the county seat and the most populous city of Pueblo County, Colorado, United States. The population was 106,595 in 2010 census, making it the 246th most populous city in the United States....

, he hired the eccentric "Old Bill" Williams

William S. Williams

William S. Williams was a noted mountain man and frontiersman.-Birth:William Sherley Williams, known as Old Bill Williams, was born January 3, 1787 in Horse Creek North Carolina.-Early life:...

and moved on.

Had Frémont continued up the Arkansas, he might have succeeded. On November 25 at what is now Florence, Colorado

Florence, Colorado

The City of Florence is a Statutory City located in Fremont County, Colorado, United States. The population was 3,653 at the 2000 census.ADX Florence, the only federal Supermax prison in the United States, is located south of Florence in an unincorporated area in Fremont County...

, he turned sharply south. By the time his party crossed the Sangre de Cristo Range

Sangre de Cristo Range

The Sangre de Cristo Range, called the East Range locally in the San Luis Valley, is a narrow mountain range of the Rocky Mountains running north and south along the east side of the Rio Grande Rift in southern Colorado in the United States...

via Mocha Pass, they had already experienced days of bitter cold, blinding snow and difficult travel. Some of the party, including the guide Wootton, had already turned back, concluding further travel would be impossible. Although the passes through the Sangre de Cristo had proven too steep for a railroad, Frémont pressed on. From this point the party might still have succeeded had they gone up the Rio Grande

Rio Grande

The Rio Grande is a river that flows from southwestern Colorado in the United States to the Gulf of Mexico. Along the way it forms part of the Mexico – United States border. Its length varies as its course changes...

to its source, or gone by a more northerly route, but the route they took brought them to the very top of Mesa Mountain. By December 12, on Boot Mountain it took ninety minutes to progress three hundred yards. Mules began dying and by 20 December only 59 animals remained alive. It was not until December 22 that Frémont acknowledged the party needed to regroup and be resupplied. They began to make their way to Taos

Taos, New Mexico

Taos is a town in Taos County in the north-central region of New Mexico, incorporated in 1934. As of the 2000 census, its population was 4,700. Other nearby communities include Ranchos de Taos, Cañon, Taos Canyon, Ranchitos, and El Prado. The town is close to Taos Pueblo, the Native American...

, New Mexico

New Mexico

New Mexico is a state located in the southwest and western regions of the United States. New Mexico is also usually considered one of the Mountain States. With a population density of 16 per square mile, New Mexico is the sixth-most sparsely inhabited U.S...

. By the time the last surviving member of the expedition made it to Taos on February 12, 1849, 10 of the party were dead. Except for the efforts of member Alexis Godey, another 15 would have been lost. After recuperating in Taos, Frémont and only a few of the men left for California via an established southern trade route.

U.S. Senator and Republican presidential candidate: "Free Soil, Free Men, and Frémont"

Frémont was one of the first two senatorsUnited States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

from California, serving only a few months, from 1850 to 1851. He had previously served as Military Governor of California in 1847.

Frémont was the first presidential candidate of the new Republican Party in 1856. It used the slogan "Free Soil, Free Men, and Frémont" to crusade for free farms (homesteads) and against the Slave Power

Slave power

The Slave Power was a term used in the Northern United States to characterize the political power of the slaveholding class of the South....

. As was typical in presidential campaigns, the candidates stayed at home and said little. The Democrats meanwhile counter-crusaded against the Republicans, warning that a victory by Frémont would bring civil war. They also raised a host of issues, alleging Frémont was a Catholic and had a poor military record. Frémont's powerful father-in-law, Senator Benton, praised Frémont but announced his support for the Democratic candidate James Buchanan

James Buchanan

James Buchanan, Jr. was the 15th President of the United States . He is the only president from Pennsylvania, the only president who remained a lifelong bachelor and the last to be born in the 18th century....

.

At the time of his campaign he lived in Staten Island

Staten Island

Staten Island is a borough of New York City, New York, United States, located in the southwest part of the city. Staten Island is separated from New Jersey by the Arthur Kill and the Kill Van Kull, and from the rest of New York by New York Bay...

, New York

New York

New York is a state in the Northeastern region of the United States. It is the nation's third most populous state. New York is bordered by New Jersey and Pennsylvania to the south, and by Connecticut, Massachusetts and Vermont to the east...

. The campaign was headquartered near his home in St. George. He placed second to James Buchanan

James Buchanan

James Buchanan, Jr. was the 15th President of the United States . He is the only president from Pennsylvania, the only president who remained a lifelong bachelor and the last to be born in the 18th century....

in a three-way election

United States presidential election, 1856

The United States presidential election of 1856 was an unusually heated contest that led to the election of James Buchanan, the ambassador to the United Kingdom. Republican candidate John C. Frémont condemned the Kansas–Nebraska Act and crusaded against the expansion of slavery, while Democrat...

; he did not carry the state of California.

Arizona Territory

The Territory of Arizona was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from February 24, 1863 until February 14, 1912, when it was admitted to the Union as the 48th state....

for several years, though he spent little time in the territory; he was asked to resume his duties or resign, and chose resignation.

Civil War

Frémont later served as a major general in the American Civil WarAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

, including a controversial term as commander of the Army's Department of the West

Department of the West

The Department of the West, later known as the Western Department, was a major command of the United States Army during the 19th century. It oversaw the military affairs in the country west of the Mississippi River to the borders of California and Oregon.-Organization:The Department was first...

from May to November 1861. Frémont replaced William S. Harney

William S. Harney

William Selby Harney was a cavalry officer in the U.S. Army during the Mexican-American War and the Indian Wars. He was born in what is today part of Nashville, Tennessee but at the time was known as Haysborough....

, who had negotiated the Harney-Price Truce, which permitted Missouri

Missouri

Missouri is a US state located in the Midwestern United States, bordered by Iowa, Illinois, Kentucky, Tennessee, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Kansas and Nebraska. With a 2010 population of 5,988,927, Missouri is the 18th most populous state in the nation and the fifth most populous in the Midwest. It...

to remain neutral in the conflict as long as it did not send men or supplies to either side.

Frémont ordered his Gen. Nathaniel Lyon

Nathaniel Lyon

Nathaniel Lyon was the first Union general to be killed in the American Civil War and is noted for his actions in the state of Missouri at the beginning of the conflict....

to formally bring Missouri into the Union

Union (American Civil War)

During the American Civil War, the Union was a name used to refer to the federal government of the United States, which was supported by the twenty free states and five border slave states. It was opposed by 11 southern slave states that had declared a secession to join together to form the...

cause. Lyon had been named the temporary commander of the Department of the West, before Frémont ultimately replaced Lyon. Lyon, in a series of battles, evicted Gov. Claiborne Jackson and installed a pro-Union government. After Lyon was killed in the Battle of Wilson's Creek

Battle of Wilson's Creek

The Battle of Wilson's Creek, also known as the Battle of Oak Hills, was fought on August 10, 1861, near Springfield, Missouri, between Union forces and the Missouri State Guard, early in the American Civil War. It was the first major battle of the war west of the Mississippi River and is sometimes...

in August, Frémont imposed martial law

Martial law

Martial law is the imposition of military rule by military authorities over designated regions on an emergency basis— only temporary—when the civilian government or civilian authorities fail to function effectively , when there are extensive riots and protests, or when the disobedience of the law...

in the state, confiscating secessionists' private property and emancipating slaves

Frémont Emancipation

The Frémont Emancipation was part of a military proclamation issued by Major General John C. Frémont on August 30, 1861 in St. Louis, Missouri during the early months of the American Civil War...

.

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln was the 16th President of the United States, serving from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. He successfully led his country through a great constitutional, military and moral crisis – the American Civil War – preserving the Union, while ending slavery, and...

, fearing the order would tip Missouri (and other slave states in Union control) to the southern cause, asked Frémont to revise the order. Frémont refused to do so, and sent his wife to plead the case. Lincoln responded by publicly revoking the proclamation and relieving Frémont of command on November 2, 1861, simultaneous to a War Department report detailing Frémont's iniquities as a major general. In March 1862 he was placed in command of the Mountain Department of Virginia

Virginia

The Commonwealth of Virginia , is a U.S. state on the Atlantic Coast of the Southern United States. Virginia is nicknamed the "Old Dominion" and sometimes the "Mother of Presidents" after the eight U.S. presidents born there...

, Tennessee

Tennessee

Tennessee is a U.S. state located in the Southeastern United States. It has a population of 6,346,105, making it the nation's 17th-largest state by population, and covers , making it the 36th-largest by total land area...

and Kentucky

Kentucky

The Commonwealth of Kentucky is a state located in the East Central United States of America. As classified by the United States Census Bureau, Kentucky is a Southern state, more specifically in the East South Central region. Kentucky is one of four U.S. states constituted as a commonwealth...

.

Early in June 1862 Frémont pursued the Confederate Gen. Stonewall Jackson

Stonewall Jackson

ຄຽשת״ׇׂׂׂׂ֣|birth_place= Clarksburg, Virginia |death_place=Guinea Station, Virginia|placeofburial=Stonewall Jackson Memorial CemeteryLexington, Virginia|placeofburial_label= Place of burial|image=...

for eight days, finally engaging him at Battle of Cross Keys

Battle of Cross Keys

The Battle of Cross Keys was fought on June 8, 1862, in Rockingham County, Virginia, as part of Confederate Army Maj. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's campaign through the Shenandoah Valley during the American Civil War...

on June 8. Jackson slipped away after the battle, saving his army.

When the Army of Virginia

Army of Virginia

The Army of Virginia was organized as a major unit of the Union Army and operated briefly and unsuccessfully in 1862 in the American Civil War. It should not be confused with its principal opponent, the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, commanded by Robert E...

was created June 26, to include Gen. Frémont's corps, with John Pope

John Pope (military officer)

John Pope was a career United States Army officer and Union general in the American Civil War. He had a brief but successful career in the Western Theater, but he is best known for his defeat at the Second Battle of Bull Run in the East.Pope was a graduate of the United States Military Academy in...

in command, Frémont declined to serve on the grounds that he was senior to Pope and for personal reasons. He then went to New York where he remained throughout the war, expecting a command, but none was given to him.

Radical Republican presidential candidacy

In 1860 the Republicans nominated Abraham LincolnAbraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln was the 16th President of the United States, serving from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. He successfully led his country through a great constitutional, military and moral crisis – the American Civil War – preserving the Union, while ending slavery, and...

for president, who won the presidency and then ran for reelection in 1864. The Radical Republicans, a group of hard-line abolitionists

Abolitionism

Abolitionism is a movement to end slavery.In western Europe and the Americas abolitionism was a movement to end the slave trade and set slaves free. At the behest of Dominican priest Bartolomé de las Casas who was shocked at the treatment of natives in the New World, Spain enacted the first...

, were upset with Lincoln's positions on the issues of slavery and post-war reconciliation with the southern states. On May 31, 1864, they nominated Frémont for president. This fissure in the Republican Party divided the party into two factions: the anti-Lincoln Radical Republicans, who nominated Frémont, and the pro-Lincoln Republicans. Frémont abandoned his political campaign in September 1864, after he brokered a political deal in which Lincoln removed Postmaster General

United States Postmaster General

The United States Postmaster General is the Chief Executive Officer of the United States Postal Service. The office, in one form or another, is older than both the United States Constitution and the United States Declaration of Independence...

Montgomery Blair

Montgomery Blair

Montgomery Blair , the son of Francis Preston Blair, elder brother of Francis Preston Blair, Jr. and cousin of B. Gratz Brown, was a politician and lawyer from Maryland...

from office.

Later life

The state of MissouriMissouri

Missouri is a US state located in the Midwestern United States, bordered by Iowa, Illinois, Kentucky, Tennessee, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Kansas and Nebraska. With a 2010 population of 5,988,927, Missouri is the 18th most populous state in the nation and the fifth most populous in the Midwest. It...

took possession of the Pacific Railroad

Pacific Railroad

The Pacific Railroad was a railroad based in the U.S. state of Missouri. It was a predecessor of both the Missouri Pacific Railroad and St. Louis-San Francisco Railway.The Pacific was chartered by Missouri in 1849 to extend "from St...

in February 1866, when the company defaulted in its interest payment. In June 1866 the state, at private sale, sold the road to Frémont. Frémont reorganized the assets of the Pacific Railroad as the Southwest Pacific Railroad in August 1866. In less than a year (June 1867), the railroad was repossessed by the state of Missouri after Frémont was unable to pay the second installment on his purchase.

From 1878 to 1881 Frémont was governor of the Arizona Territory

Arizona Territory

The Territory of Arizona was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from February 24, 1863 until February 14, 1912, when it was admitted to the Union as the 48th state....

. Destitute, the family depended on the publication earnings of his wife Jessie.

Frémont lived on Staten Island in retirement. He died in New York City

New York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

in 1890 of peritonitis

Peritonitis

Peritonitis is an inflammation of the peritoneum, the serous membrane that lines part of the abdominal cavity and viscera. Peritonitis may be localised or generalised, and may result from infection or from a non-infectious process.-Abdominal pain and tenderness:The main manifestations of...

, a forgotten man. He was buried in Rockland Cemetery, Sparkill

Sparkill, New York

Sparkill, formerly known as Tappan Sloat, is an affluent, suburban hamlet in the Town of Orangetown, Rockland County, New York, United States located north of Palisades; east of Tappan; south of Piermont and west of the Hudson River...

, New York

New York

New York is a state in the Northeastern region of the United States. It is the nation's third most populous state. New York is bordered by New Jersey and Pennsylvania to the south, and by Connecticut, Massachusetts and Vermont to the east...

.

Plants

Frémont collected a number of plants on his expeditions, including the first recorded discovery of the Single-leaf PinyonSingle-leaf Pinyon

The Single-leaf Pinyon, ', is a pine in the pinyon pine group, native to the United States and northwest Mexico. The range is in southernmost Idaho, western Utah, Arizona, southwest New Mexico, Nevada, eastern and southern California and northern Baja California.It occurs at moderate altitudes from...

by a European American. The genus of the California Flannelbush (Fremontodendron californicum) is named for him, as are the species names of many other plants, including the chaff bush eytelia (Amphipappus fremontii), Western rosinweed (Calycadenia fremontii

Calycadenia fremontii

Calycadenia fremontii is a species of flowering plant in the daisy family known by the common name Frémont's western rosinweed . It is native to northern California and Oregon, where it is a common member of the flora in several types of habitat in the mountains, foothills, and valleys. This annual...

), pincushion flower (Chaenactis fremontii

Chaenactis fremontii

Chaenactis fremontii, with the common names Fremont's pincushion and Desert pincushion, is a species of annual wildflower in the daisy family. Both the latter common name, and the specific epithet are named for John C. Frémont....

), goosefoot (Chenopodium fremontii

Chenopodium fremontii

Chenopodium fremontii is a species of flowering plant in the amaranth family known by the common name Frémont's goosefoot. Both the species' specific epithet, and the common name derive from the 19th century western pioneer John C. Frémont....

), silk tassel (Garrya fremontii

Garrya fremontii

Garrya fremontii is a species of flowering shrub known by several common names, including California fever bush, bearbrush, and Frémont's silktassel. Both the latter name, and the plant's specific epithet are derived from John C. Frémont...

), moss gentian (Gentiana fremontii), vernal pool goldfields (Lasthenia fremontii

Lasthenia fremontii

Lasthenia fremontii is a species of flowering plant in the daisy family known by the common name Frémont's goldfields . It is endemic to the California Central Valley, where it grows in vernal pools and meadows. This is an annual herb approaching a maximum height near 35 centimeters...

), tidytips (Layia fremontii

Layia fremontii

Layia fremontii is a species of flowering plant in the daisy family known by the common name Frémont's tidytips. Both its common name, and its specific epithet are derived from John C...

), desert pepperweed (Lepidium fremontii

Lepidium fremontii

Lepidium fremontii is a species of flowering plant in the mustard family which is native to the southwestern United States, where it grows on sandy desert flats and the rocky slopes of nearby hills and mountains. It takes its scientific name from John C. Frémont.-Description:L...

), desert boxthorn (Lycium fremontii

Lycium fremontii

Lycium fremontii is a species of flowering plant in the nightshade family, Solanaceae, that is native to northwestern Mexico and the southernmost mountains and deserts of California and Arizona in the United States...

), barberry (Mahonia fremontii

Mahonia fremontii

Mahonia fremontii is a species of barberry known by the common name Frémont's mahonia .-Distribution:...

), bush mallow (Malacothamnus fremontii

Malacothamnus fremontii

Malacothamnus fremontii is a species of flowering plant in the mallow family known by the common name Frémont's bushmallow .-Description:...

), monkeyflower (Mimulus fremontii

Mimulus fremontii

Mimulus fremontii is a species of monkeyflower known by the common name Frémont's monkeyflower. It is native to California and Baja California, where it grows in mountain and desert habitat, especially moist or disturbed areas.-Description:...

), phacelia (Phacelia fremontii

Phacelia fremontii