Military history of the Revolt of the Comuneros

Encyclopedia

Military conflict in the Revolt of the Comuneros spanned from 1520 to 1521. The Revolt began with mobs of urban workers attacking government officials, grew to low-level combat between small militias, and eventually saw massed armies fighting battles and sieges. The comunero rebels gained control of most of central Castile quite quickly, and the royal army was in shambles by September 1520. However, the comuneros alienated much of the landed nobility, and the nobility's personal armies helped bolster the royalist forces. The Battle of Tordesillas in December 1520 would prove a major setback for the rebels, and the most important army of the comuneros was destroyed at the Battle of Villalar

in April 1521.

This article is arranged geographically, and then chronologically within each region. The royalists tended to maintain the same commanders and armies in each area, with the one major exception of when the Constable of Castile moved out of Burgos to unite with the Admiral and crush the Comuneros at Villalar. The Comuneros leaders switched between regions somewhat more, especially Bishop Acuña, but still maintained regional militias ultimately.

The most important fighting of the war, and where the fighting was mostly by organized armies rather than raiding militia bands, took part in the north-central part of the Meseta—Old Castile

, which contained the capital of Valladolid

, the temporary capital of both sides Tordesillas

, and the stronghold of the Admiral of Castile, Medina de Rioseco

. Each of these three cities was highly fortified and sought after. A decent amount of combat took place to the north around Burgos

and the Basque country as well, where the Constable of Castile vied against Bishop Acuña's raids and the Count of Salvatierra. The southern part of the Meseta, New Castile, was a bastion of comunero support. The royalists never were able to deploy much in the way of armies here, depending on their allies in the Knights of St. John and the local nobility, but some notable events in the war did take place there. The rest of the country was mostly quiet: Andalusia on the southern coast was almost uniformly pro-royalist, as was Extramadura and Galicia.

campaign. With the central cities of Castile on their side, no expensive foreign entanglements to fund, and a tendency to loot and repossess property of the opposed nobility, the rebels were well-funded.

However, the lack of noble support meant that cavalry were difficult to find. Additionally, the city dwellers the comuneros recruited often lacked much appreciation for the peasantry, and for some actively looked down upon them. The countryside was initially strongly pro-comunero, but the ravages of the comunero army would eventually cost them some support.

The comunero army also struggled from factionalism from within, and the lack of a clear commander-in-chief. Each militia was generally loyal to its home city first, and only marched with a main comunero army given permission. When Pedro Girón was appointed commander of the army by the Santa Junta, they made it clear that he would only directly control forces recruited by himself and the small army loyal to the Junta. Juan de Padilla withdrew his Toledo militia in protest of losing the appointment. When Padilla later came to take the position, he had better luck in convincing the various militias to follow him, but this was more due to his popularity than his authority.

The need to constantly search out new towns and manors to sack and pillage also made slower or defensive strategies difficult for the comuneros to implement. Whenever the army defended one place and retrenched, some militias would often separate and return home. This would require new recruitment to make up the loss, and thus the army was less experienced than it could have been.

The royalist cause's most important allies were the landed nobility, many of whom threw their allegiance behind King Charles after seeing the comuneros support peasant rebellions against them. They offered a powerful combination of militarily experienced commanders, disciplined troops, and expensive horse cavalry

. However, they were also unreliable. Many nobles' first goal was to protect their own lands, and crushing the rebellion but losing their own holdings would be a loss. As such, the Regents often had difficulty rallying the noble forces to make a combined army. After the victory at Toredesillas, for example, many royal guards were dismissed due to lack of funds to pay them, and many noble-controlled armies returned to their home areas, greatly endangering the defense of Tordesillas and preventing any new offense.

After the burning of Medina del Campo, the royalist cause had to struggle with negative perceptions from the populace. As such, the royalists took considerably greater precautions than the comuneros to avoid enraging the countryside. For most battles, the royalist troops were forbidden from looting captured cities for income. This caused considerable dissatisfaction among the ranks and exacerbated the problem of the low pay for the soldiers, but also saved the royalist cause from even further distaste from the populace. The commanders of the royal army were also brave enough to dismiss unnecessary additional troops. Untrained peasant levies were unlikely to be very effective on the battlefield, but would be additional bellies to feed and could easily offend the countryside with undisciplined looting.

Loyalty was an additional concern that the royalist cause faced. New recruits from the cities of the Meseta were unlikely to be terribly loyal, and might even leak information. As a result, the royalist armies generally used poor Galicians from the North for additional troops.

and its Moriscos. It was crucial for the government to act unified to maintain stability; if some cities of Andalusia were to join the Comunidades and others not, a civil war among the Spanish Christians would invite a revolt among the Moriscos. The economic situation was different as well; Andalusia was seeing the beginnings of what would become a vast stream of wealth from Spain's overseas trade and conquests. While Andalusia's nobles were still powerful, many opportunities existed for all classes. In the Meseta, the bourgeoise and lower classes had tasted prosperity for a time under Isabella, but had seen their gains fade in the past twenty years, which fed bitterness at the nobility and helped spark revolts. Furthermore, Andalusia simply did not see the change in government in the two Castiles as necessarily their concern. With the slower and less frequent travel of the day, some in Andalusia simply thought the matter did not concern them, and if the Castiles wished a new government that did not necessarily have any bearing on Andalusia.

The towns in the north of Andalusia in the mountains, away from the coast, were more connected with the Castiles. Jaén

, Úbeda

, and Baeza

all favored the Comunidades during the early stages of the revolt. Once the Andalusian nobles got word of this, they sent a sizable force to retake these small cities for the king. The Captain-General of Granada, who was also the Marquis of Mondéjar and Count of Tendilla (same person bearing all three titles), led a force of some 1,500 men in September to retake Jaén. He executed the three leading members of the Comunidad there, lashed others, and then pardoned the rest of the town. Murcia

also joined the Comunidades, but eventually came back to the royal forces much later and by persuasion rather than force.

In coastal Andalusia, there was sporadic discontent, but few attempted rebellions. Two notable attempted rebellions occurred in Seville

, but nothing much came of either one. The first was led by Juan de Figueroa, a member of the powerful Ponce family. On Sunday, September 16, he proclaimed the Comunidad and took over the lightly fortified Alcázar of Seville. The rebellion was quickly crushed the next day by the Duke of Medina-Sidonia, a member of the rival Guzmán family, and Figueroa was lightly wounded. The incident was treated as a youthful indiscretion, and Figeruoa quickly pardoned, leading some historians to treat the matter as simply the latest grab for power between the two feuding noble houses. A later attempt, la Feria y Pendón Verde ("The Fair and the Green Flag") led by lower classes, seemingly confirms this explanation. The nobility of both houses united to put down the riots, which lasted three days, suggesting the first revolt was more about which noble house would have power.

To coordinate their activities, the towns of Andalusia received permission from the government to set up their own Congress at Rambla. They had requested it on October 24, 1520, and actually convened the assembly on January 20, 1521. The Rambla Congress admonished towns to return to the royal government and organized a military force of 4,000 infantry and 800 cavalry to be ready should the need to quickly suppress a Morisco rebellion arose. Still, the Rambla Congress worried some royalists in the Meseta, as should the war turn against the royal government, it would provide an easy mechanism for Andalusia to coordinate itself and defect as one (removing the worries of a civil war giving the Moriscos an opening). The Admiral of Castile wrote to King Charles that:

As the war never significantly turned against the royal government, the Admiral's fears were not realized. Andalusia also sent an army off to intervene in the Revolt of the Brotherhoods. The Andalusian army helped turn the tide against the rebels there by winning the Battle of Oriola in crushing fashion.

was where the majority of the large battles of the war took place. The area around Tordesillas

, Valladolid

, and Medina de Rioseco

was particularly contested - the three most decisive battles of the war, Tordesillas, Torrelobatón, and Villalar all took place in this area.

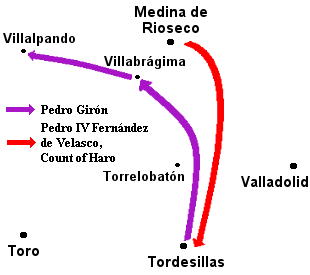

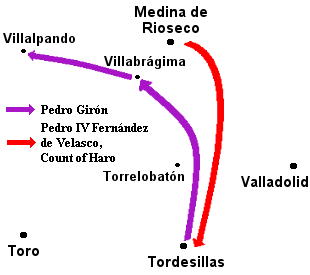

In late November 1520, both armies took positions between Medina de Rioseco and Tordesillas, and a confrontation was inevitable. With Pedro Girón in command, the army of the comuneros advanced on Medina de Rioseco

In late November 1520, both armies took positions between Medina de Rioseco and Tordesillas, and a confrontation was inevitable. With Pedro Girón in command, the army of the comuneros advanced on Medina de Rioseco

, following the orders of the Junta. Girón established his headquarters in Villabrágima

, a town merely 8 kilometres (5 mi) from the royalist army. The royalists occupied nearby villages to cut communication lines back to other comuneros.

This situation continued until December 2, when Girón, apparently thinking the royal army would remain entrenched, moved his forces west to the small town of Villalpando

. The town surrendered the next day without resistance, and the troops began looting the estates in the area. However, with this movement, the comuneros left the path to Tordesillas completely unprotected. The royal army took advantage of the blunder, marching by night on December 4 and occupying Tordesillas the next day. The small rebel garrison was overwhelmed.

Seizure of Tordesillas marked a serious defeat for the comuneros, who lost Queen Joanna

and with her their claim to legitimacy. In addition, thirteen representatives of the Junta were imprisoned, though others fled and escaped. Morale fell among the rebels, and much angry criticism was directed towards Pedro Girón for his maneuvering of the troops out of position and for his failure to attempt to retake Tordesillas or capture Medina de Rioseco. Girón was obliged to resign from his post and withdrew from the war. Juan de Padilla returned from Toledo to be appointed the new Captain-General of the comunero forces.

After the triumph in Tordesillas, Cardinal Adrian had to face the continuing paucity of funds in the royal coffers and the fickleness of his noble allies. Many nobles returned with their armies to their domains to guard them against the continuing peasant revolts that were breaking out. The treasury situation had deteriorated to the point that some soldiers had to be released for lack of funds to pay them. As a result, Adrian, the Count of Haro, and the Admiral were able to do little but fortify their holdings, and not attempt any further advances.

all of the inhabitants, at which point the castle surrendered. The defenders did secure an agreement to spare half of the goods inside the castle, thus avoiding further looting.

The victory in Torrelobatón lifted the spirits of the rebel camp while worrying the royalists about the rebel advance, exactly as Padilla hoped. The faith of the nobles in Cardinal Adrian was once again shook, as he was accused of having done nothing to avoid losing Torrelobatón. The Constable of Castile began to send troops to the Tordesillas area to contain the rebels and prevent any further advances.

In late March 1521, the royalist side moved to combine their armies and threaten Torrelobatón

, a rebel stronghold. The Constable of Castile

began to move his troops (including soldiers recently transferred from the defense of Navarre) southwest from Burgos to meet with the Admiral

's forces near Tordesillas

. This was possible due to the comunero-aligned Count of Salvatierra's force being caught up in the siege of Medina de Pomar

; the Count's forces had previously been enough of a threat to force the Constable to maintain a large army to defend Burgos. The Constable's army was approximately 3,000 infantry, 600 cavalry, 2 cannon

s, 2 culverin

, and 5 light artillery pieces. His army took up positions in Becerril de Campos

, near Palencia

. Meanwhile, the comuneros reinforced their troops at Torrelobatón, which was far less secure than the comuneros preferred. Their forces were suffering from desertions, and the presence of royalist artillery would make Torrelobatón's castle vulnerable. They had two strategic possibilities: prevent the Constable and Admiral from united their forces by striking at the Constable while he was still on the field, or else low-level harrying operations to try and slow the Constable down. The comuneros did neither, and thus allowed the Constable to approach nearly unchecked.

, considered withdrawing to Toro to seek reinforcements in early April, but wavered. He delayed his decision until the early hours of April 23, losing considerable time and allowing the royalists to unite their forces in Peñaflor

.

The combined royalist army pursued the comuneros. Once again, the royalists had a strong advantage in cavalry, with their army consisting of 6,000 infantry and 2,400 cavalry against Padilla's 7,000 infantry and 400 cavalry. Heavy rain slowed Padilla's infantry more than the royalist cavalry and rendered the primitive firearms of the rebels' 1,000 arquebusiers nearly useless. Padilla hoped to reach the relative safety of Toro and the heights of Vega de Valdetronco

, but his infantry was too slow. He gave battle with the harrying royalist cavalry at the town of Villalar. The cavalry charges scattered the rebel ranks, and the battle became a slaughter. There were an estimated 500–1,000 rebel casualties and many desertions.

The three most important leaders of the rebellion were captured: Juan de Padilla

, Juan Bravo, and Francisco Maldonado

. They were beheaded the next morning in the Plaza of Villalar, with a large portion of the royalist nobility present. The remains of the rebel army at Villalar fragmented, with some attempting to join Acuña's army near Toledo and others fleeing to Portugal.

and attacked the Spanish-occupied portion of Navarre. If the comuneros had held out slightly longer, it might have saved them, but by the time of the invasion the Battle of Villalar

had already happened. Instead of an opportunity to win the war, the invasion instead became a way for former comunero cities nervous about potential reprisals to prove their loyalty by sending large contingents to fight the French and Navarrese. An even larger Castilian army attacked the French and crushingly defeated them at the Battle of Noáin

on June 30, 1521.

Battle of Villalar

The Battle of Villalar was a battle in the Revolt of the Comuneros fought on April 23, 1521 near the town of Villalar in Valladolid province, Spain. The royalist supporters of King Charles I won a crushing victory over the comuneros rebels. Three of the most important rebel leaders were...

in April 1521.

This article is arranged geographically, and then chronologically within each region. The royalists tended to maintain the same commanders and armies in each area, with the one major exception of when the Constable of Castile moved out of Burgos to unite with the Admiral and crush the Comuneros at Villalar. The Comuneros leaders switched between regions somewhat more, especially Bishop Acuña, but still maintained regional militias ultimately.

The most important fighting of the war, and where the fighting was mostly by organized armies rather than raiding militia bands, took part in the north-central part of the Meseta—Old Castile

Old Castile

Old Castile is a historic region of Spain, which included territory that later corresponded to the provinces of Santander , Burgos, Logroño , Soria, Segovia, Ávila, Valladolid, Palencia....

, which contained the capital of Valladolid

Valladolid

Valladolid is a historic city and municipality in north-central Spain, situated at the confluence of the Pisuerga and Esgueva rivers, and located within three wine-making regions: Ribera del Duero, Rueda and Cigales...

, the temporary capital of both sides Tordesillas

Tordesillas

Tordesillas is a town and municipality in the province of Valladolid, Castile and León, central Spain.It is located 25 km southwest of the provincial capital, Valladolid at an elevation of 704 meters. The population was c. 9,000 in 2009....

, and the stronghold of the Admiral of Castile, Medina de Rioseco

Medina de Rioseco

Medina de Rioseco is a municipality located in the province of Valladolid, Castile and León, Spain. According to the 2004 census , the municipality has a population of 5,037 inhabitants. During the Peninsular War, it was here that the Battle of Medina del Rioseco took place on July 14,...

. Each of these three cities was highly fortified and sought after. A decent amount of combat took place to the north around Burgos

Burgos

Burgos is a city of northern Spain, historic capital of Castile. It is situated at the edge of the central plateau, with about 178,966 inhabitants in the city proper and another 20,000 in its suburbs. It is the capital of the province of Burgos, in the autonomous community of Castile and León...

and the Basque country as well, where the Constable of Castile vied against Bishop Acuña's raids and the Count of Salvatierra. The southern part of the Meseta, New Castile, was a bastion of comunero support. The royalists never were able to deploy much in the way of armies here, depending on their allies in the Knights of St. John and the local nobility, but some notable events in the war did take place there. The rest of the country was mostly quiet: Andalusia on the southern coast was almost uniformly pro-royalist, as was Extramadura and Galicia.

Comunero forces

The comuneros generally drew their strength from the cities and the urban militias to form their armies. They also aggressively recruited former royal guards who had deserted due to low pay, especially veterans of recent campaigns in Africa such as the DjerbaDjerba

Djerba , also transliterated as Jerba or Jarbah, is, at 514 km², the largest island of North Africa, located in the Gulf of Gabes, off the coast of Tunisia.-Description:...

campaign. With the central cities of Castile on their side, no expensive foreign entanglements to fund, and a tendency to loot and repossess property of the opposed nobility, the rebels were well-funded.

However, the lack of noble support meant that cavalry were difficult to find. Additionally, the city dwellers the comuneros recruited often lacked much appreciation for the peasantry, and for some actively looked down upon them. The countryside was initially strongly pro-comunero, but the ravages of the comunero army would eventually cost them some support.

The comunero army also struggled from factionalism from within, and the lack of a clear commander-in-chief. Each militia was generally loyal to its home city first, and only marched with a main comunero army given permission. When Pedro Girón was appointed commander of the army by the Santa Junta, they made it clear that he would only directly control forces recruited by himself and the small army loyal to the Junta. Juan de Padilla withdrew his Toledo militia in protest of losing the appointment. When Padilla later came to take the position, he had better luck in convincing the various militias to follow him, but this was more due to his popularity than his authority.

The need to constantly search out new towns and manors to sack and pillage also made slower or defensive strategies difficult for the comuneros to implement. Whenever the army defended one place and retrenched, some militias would often separate and return home. This would require new recruitment to make up the loss, and thus the army was less experienced than it could have been.

Royalist forces

The royalist-aligned forces consisted of two groups: the royal army, a national army that answered to the Regents, and the independent armies of the nobles. Part of the reason the government got into the mess to begin with was due to its complete mendacity due to money leaving the kingdom to pay foreign debts. The royal administration, and thus its army, suffered from a crippling lack of funding the entire war. Even after the war, some royal guards who had defected reported laughing at those who had followed the king, saying that "while the comunidad paid them every day, their opponents were not so well paid." In the later conflict against the French in Navarre, an army even mutinied after being given only a month's worth of pay when owed four months of back pay.The royalist cause's most important allies were the landed nobility, many of whom threw their allegiance behind King Charles after seeing the comuneros support peasant rebellions against them. They offered a powerful combination of militarily experienced commanders, disciplined troops, and expensive horse cavalry

Cavalry

Cavalry or horsemen were soldiers or warriors who fought mounted on horseback. Cavalry were historically the third oldest and the most mobile of the combat arms...

. However, they were also unreliable. Many nobles' first goal was to protect their own lands, and crushing the rebellion but losing their own holdings would be a loss. As such, the Regents often had difficulty rallying the noble forces to make a combined army. After the victory at Toredesillas, for example, many royal guards were dismissed due to lack of funds to pay them, and many noble-controlled armies returned to their home areas, greatly endangering the defense of Tordesillas and preventing any new offense.

After the burning of Medina del Campo, the royalist cause had to struggle with negative perceptions from the populace. As such, the royalists took considerably greater precautions than the comuneros to avoid enraging the countryside. For most battles, the royalist troops were forbidden from looting captured cities for income. This caused considerable dissatisfaction among the ranks and exacerbated the problem of the low pay for the soldiers, but also saved the royalist cause from even further distaste from the populace. The commanders of the royal army were also brave enough to dismiss unnecessary additional troops. Untrained peasant levies were unlikely to be very effective on the battlefield, but would be additional bellies to feed and could easily offend the countryside with undisciplined looting.

Loyalty was an additional concern that the royalist cause faced. New recruits from the cities of the Meseta were unlikely to be terribly loyal, and might even leak information. As a result, the royalist armies generally used poor Galicians from the North for additional troops.

Andalusia: The Southern coast

In general, Andalusia was fairly quiet during the war. A variety of reasons exist for this. Among the nobles, there was a great investment in the project of Hispanicizing the recently conquered GranadaEmirate of Granada

The Emirate of Granada , also known as the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada , was an emirate established in 1238 following the defeat of Muhammad an-Nasir of the Almohad dynasty by an alliance of Christian kingdoms at the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa in 1212...

and its Moriscos. It was crucial for the government to act unified to maintain stability; if some cities of Andalusia were to join the Comunidades and others not, a civil war among the Spanish Christians would invite a revolt among the Moriscos. The economic situation was different as well; Andalusia was seeing the beginnings of what would become a vast stream of wealth from Spain's overseas trade and conquests. While Andalusia's nobles were still powerful, many opportunities existed for all classes. In the Meseta, the bourgeoise and lower classes had tasted prosperity for a time under Isabella, but had seen their gains fade in the past twenty years, which fed bitterness at the nobility and helped spark revolts. Furthermore, Andalusia simply did not see the change in government in the two Castiles as necessarily their concern. With the slower and less frequent travel of the day, some in Andalusia simply thought the matter did not concern them, and if the Castiles wished a new government that did not necessarily have any bearing on Andalusia.

The towns in the north of Andalusia in the mountains, away from the coast, were more connected with the Castiles. Jaén

Jaén, Spain

Jaén is a city in south-central Spain, the name is derived from the Arabic word Jayyan, . It is the capital of the province of Jaén. It is located in the autonomous community of Andalusia....

, Úbeda

Úbeda

Úbeda is a town in the province of Jaén in Spain's autonomous community of Andalusia, with some 35,600 inhabitants. Both this city and the neighboring city of Baeza benefited from extensive patronage in the early 16th century resulting in the construction of a series of Renaissance style palaces...

, and Baeza

Baeza

Baeza is a town of approximately 16,200 inhabitants in Andalusia, Spain, in the province of Jaén, perched on a cliff in the Loma de Baeza, a mountain range between the river Guadalquivir on the south and its tributary the Guadalimar on the north. It is chiefly known today as having many of the...

all favored the Comunidades during the early stages of the revolt. Once the Andalusian nobles got word of this, they sent a sizable force to retake these small cities for the king. The Captain-General of Granada, who was also the Marquis of Mondéjar and Count of Tendilla (same person bearing all three titles), led a force of some 1,500 men in September to retake Jaén. He executed the three leading members of the Comunidad there, lashed others, and then pardoned the rest of the town. Murcia

Murcia

-History:It is widely believed that Murcia's name is derived from the Latin words of Myrtea or Murtea, meaning land of Myrtle , although it may also be a derivation of the word Murtia, which would mean Murtius Village...

also joined the Comunidades, but eventually came back to the royal forces much later and by persuasion rather than force.

In coastal Andalusia, there was sporadic discontent, but few attempted rebellions. Two notable attempted rebellions occurred in Seville

Seville

Seville is the artistic, historic, cultural, and financial capital of southern Spain. It is the capital of the autonomous community of Andalusia and of the province of Seville. It is situated on the plain of the River Guadalquivir, with an average elevation of above sea level...

, but nothing much came of either one. The first was led by Juan de Figueroa, a member of the powerful Ponce family. On Sunday, September 16, he proclaimed the Comunidad and took over the lightly fortified Alcázar of Seville. The rebellion was quickly crushed the next day by the Duke of Medina-Sidonia, a member of the rival Guzmán family, and Figueroa was lightly wounded. The incident was treated as a youthful indiscretion, and Figeruoa quickly pardoned, leading some historians to treat the matter as simply the latest grab for power between the two feuding noble houses. A later attempt, la Feria y Pendón Verde ("The Fair and the Green Flag") led by lower classes, seemingly confirms this explanation. The nobility of both houses united to put down the riots, which lasted three days, suggesting the first revolt was more about which noble house would have power.

To coordinate their activities, the towns of Andalusia received permission from the government to set up their own Congress at Rambla. They had requested it on October 24, 1520, and actually convened the assembly on January 20, 1521. The Rambla Congress admonished towns to return to the royal government and organized a military force of 4,000 infantry and 800 cavalry to be ready should the need to quickly suppress a Morisco rebellion arose. Still, the Rambla Congress worried some royalists in the Meseta, as should the war turn against the royal government, it would provide an easy mechanism for Andalusia to coordinate itself and defect as one (removing the worries of a civil war giving the Moriscos an opening). The Admiral of Castile wrote to King Charles that:

As the war never significantly turned against the royal government, the Admiral's fears were not realized. Andalusia also sent an army off to intervene in the Revolt of the Brotherhoods. The Andalusian army helped turn the tide against the rebels there by winning the Battle of Oriola in crushing fashion.

Old Castile: Valladolid and the Center of the Meseta

Old CastileOld Castile

Old Castile is a historic region of Spain, which included territory that later corresponded to the provinces of Santander , Burgos, Logroño , Soria, Segovia, Ávila, Valladolid, Palencia....

was where the majority of the large battles of the war took place. The area around Tordesillas

Tordesillas

Tordesillas is a town and municipality in the province of Valladolid, Castile and León, central Spain.It is located 25 km southwest of the provincial capital, Valladolid at an elevation of 704 meters. The population was c. 9,000 in 2009....

, Valladolid

Valladolid

Valladolid is a historic city and municipality in north-central Spain, situated at the confluence of the Pisuerga and Esgueva rivers, and located within three wine-making regions: Ribera del Duero, Rueda and Cigales...

, and Medina de Rioseco

Medina de Rioseco

Medina de Rioseco is a municipality located in the province of Valladolid, Castile and León, Spain. According to the 2004 census , the municipality has a population of 5,037 inhabitants. During the Peninsular War, it was here that the Battle of Medina del Rioseco took place on July 14,...

was particularly contested - the three most decisive battles of the war, Tordesillas, Torrelobatón, and Villalar all took place in this area.

Battle of Tordesillas

Medina de Rioseco

Medina de Rioseco is a municipality located in the province of Valladolid, Castile and León, Spain. According to the 2004 census , the municipality has a population of 5,037 inhabitants. During the Peninsular War, it was here that the Battle of Medina del Rioseco took place on July 14,...

, following the orders of the Junta. Girón established his headquarters in Villabrágima

Villabrágima

Villabrágima is a municipality located in the province of Valladolid, Castile and León, Spain. According to the 2004 census , the municipality has a population of 1,173 inhabitants....

, a town merely 8 kilometres (5 mi) from the royalist army. The royalists occupied nearby villages to cut communication lines back to other comuneros.

This situation continued until December 2, when Girón, apparently thinking the royal army would remain entrenched, moved his forces west to the small town of Villalpando

Villalpando

Villalpando is a municipality located in the province of Zamora, Castile and León, Spain. According to the 2004 census , the municipality has a population of 1,624 inhabitants. Formerly the town was reputed for its saltpans, the Salinas de Villapando....

. The town surrendered the next day without resistance, and the troops began looting the estates in the area. However, with this movement, the comuneros left the path to Tordesillas completely unprotected. The royal army took advantage of the blunder, marching by night on December 4 and occupying Tordesillas the next day. The small rebel garrison was overwhelmed.

Seizure of Tordesillas marked a serious defeat for the comuneros, who lost Queen Joanna

Joanna of Castile

Joanna , nicknamed Joanna the Mad , was the first queen regnant to reign over both the Crown of Castile and the Crown of Aragon , a union which evolved into modern Spain...

and with her their claim to legitimacy. In addition, thirteen representatives of the Junta were imprisoned, though others fled and escaped. Morale fell among the rebels, and much angry criticism was directed towards Pedro Girón for his maneuvering of the troops out of position and for his failure to attempt to retake Tordesillas or capture Medina de Rioseco. Girón was obliged to resign from his post and withdrew from the war. Juan de Padilla returned from Toledo to be appointed the new Captain-General of the comunero forces.

After the triumph in Tordesillas, Cardinal Adrian had to face the continuing paucity of funds in the royal coffers and the fickleness of his noble allies. Many nobles returned with their armies to their domains to guard them against the continuing peasant revolts that were breaking out. The treasury situation had deteriorated to the point that some soldiers had to be released for lack of funds to pay them. As a result, Adrian, the Count of Haro, and the Admiral were able to do little but fortify their holdings, and not attempt any further advances.

Battle of Torrelobatón

With the royal forces stationary, Padilla moved to attack. On February 21, 1521, the siege of Torrelobatón began. Outnumbered, the town nevertheless resisted for four days, thanks to its walls. The Count of Haro sallied forth from Tordesillas with his cavalry in an attempt to aid the besieged, but he had brought too few cavalry, and he did not engage Padilla or his forces. On February 25, the comuneros entered the town and subjected it to a massive looting spree as a reward to the troops. Only churches were spared. The castle resisted for another two days. The comuneros then threatened to hangHanging

Hanging is the lethal suspension of a person by a ligature. The Oxford English Dictionary states that hanging in this sense is "specifically to put to death by suspension by the neck", though it formerly also referred to crucifixion and death by impalement in which the body would remain...

all of the inhabitants, at which point the castle surrendered. The defenders did secure an agreement to spare half of the goods inside the castle, thus avoiding further looting.

The victory in Torrelobatón lifted the spirits of the rebel camp while worrying the royalists about the rebel advance, exactly as Padilla hoped. The faith of the nobles in Cardinal Adrian was once again shook, as he was accused of having done nothing to avoid losing Torrelobatón. The Constable of Castile began to send troops to the Tordesillas area to contain the rebels and prevent any further advances.

Interim maneuvers

Despite the renewed enthusiasm among the rebels, a decision was made to remain in their positions near Valladolid without pressing their advantage or launching a new attack. This caused many of the soldiers to return to their home communities, tired of waiting for salaries and new orders.In late March 1521, the royalist side moved to combine their armies and threaten Torrelobatón

Torrelobatón

Torrelobatón is a municipality located in the province of Valladolid, Castile and León, Spain. According to the 2004 census , the municipality has a population of 577 inhabitants....

, a rebel stronghold. The Constable of Castile

Constable of Castile

Constable of Castile was a title created by John I, King of Castile in 1382, to substitute the title Alférez Mayor del Reino. The constable was the second person in power in the kingdom, after the King, and his responsibility was to command the military in the absence of the ruler.In 1473 Henry IV...

began to move his troops (including soldiers recently transferred from the defense of Navarre) southwest from Burgos to meet with the Admiral

Fadrique Enríquez

Fadrique Enríquez was the 4th Admiral of Castile and played an important role in defeating the Revolt of the Comuneros.Fadrique Enríquez was the son of Alonso Enríquez and María de Velasco. He inherited his father's possessions in Palencia and the castle of Medina de Rioseco. On february 14...

's forces near Tordesillas

Tordesillas

Tordesillas is a town and municipality in the province of Valladolid, Castile and León, central Spain.It is located 25 km southwest of the provincial capital, Valladolid at an elevation of 704 meters. The population was c. 9,000 in 2009....

. This was possible due to the comunero-aligned Count of Salvatierra's force being caught up in the siege of Medina de Pomar

Medina de Pomar

Medina de Pomar is a municipality located in the province of Burgos, Castile and León, Spain. It is situated 77 km from Bilbao, and 88 km from Burgos, the capital of the province, 8 kilometres from Villarcayo and about 20 km from Espinosa de los Monteros, which are the most important towns in the...

; the Count's forces had previously been enough of a threat to force the Constable to maintain a large army to defend Burgos. The Constable's army was approximately 3,000 infantry, 600 cavalry, 2 cannon

Cannon

A cannon is any piece of artillery that uses gunpowder or other usually explosive-based propellents to launch a projectile. Cannon vary in caliber, range, mobility, rate of fire, angle of fire, and firepower; different forms of cannon combine and balance these attributes in varying degrees,...

s, 2 culverin

Culverin

A culverin was a relatively simple ancestor of the musket, and later a medieval cannon, adapted for use by the French in the 15th century, and later adapted for naval use by the English in the late 16th century. The culverin was used to bombard targets from a distance. The weapon had a...

, and 5 light artillery pieces. His army took up positions in Becerril de Campos

Becerril de Campos

Becerril de Campos is a municipality located in the province of Palencia, Castile and León, Spain. According to the 2004 census , the municipality has a population of 1,028 inhabitants.-External links:*...

, near Palencia

Palencia

Palencia is a city south of Tierra de Campos, in north-northwest Spain, the capital of the province of Palencia in the autonomous community of Castile-Leon...

. Meanwhile, the comuneros reinforced their troops at Torrelobatón, which was far less secure than the comuneros preferred. Their forces were suffering from desertions, and the presence of royalist artillery would make Torrelobatón's castle vulnerable. They had two strategic possibilities: prevent the Constable and Admiral from united their forces by striking at the Constable while he was still on the field, or else low-level harrying operations to try and slow the Constable down. The comuneros did neither, and thus allowed the Constable to approach nearly unchecked.

Battle of Villalar

The advance of the royalist armies was known to the rebels. The commander of the comunero armies, Juan de PadillaJuan Lopez de Padilla

Juan López de Padilla was an insurrectionary leader in the Castilian War of the Communities, where the people of Castile made a stand against policies of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V and his Flemish ministers.Padilla was the eldest son of the commendator of Castile...

, considered withdrawing to Toro to seek reinforcements in early April, but wavered. He delayed his decision until the early hours of April 23, losing considerable time and allowing the royalists to unite their forces in Peñaflor

Peñaflor de Hornija

Peñaflor de Hornija is a municipality located in the province of Valladolid, Castile and León, Spain. According to the 2004 census , the municipality has a population of 415 inhabitants....

.

The combined royalist army pursued the comuneros. Once again, the royalists had a strong advantage in cavalry, with their army consisting of 6,000 infantry and 2,400 cavalry against Padilla's 7,000 infantry and 400 cavalry. Heavy rain slowed Padilla's infantry more than the royalist cavalry and rendered the primitive firearms of the rebels' 1,000 arquebusiers nearly useless. Padilla hoped to reach the relative safety of Toro and the heights of Vega de Valdetronco

Vega de Valdetronco

Vega de Valdetronco is a municipality located in the province of Valladolid, Castile and León, Spain. According to the 2004 census , the municipality has a population of 162 inhabitants....

, but his infantry was too slow. He gave battle with the harrying royalist cavalry at the town of Villalar. The cavalry charges scattered the rebel ranks, and the battle became a slaughter. There were an estimated 500–1,000 rebel casualties and many desertions.

The three most important leaders of the rebellion were captured: Juan de Padilla

Juan Lopez de Padilla

Juan López de Padilla was an insurrectionary leader in the Castilian War of the Communities, where the people of Castile made a stand against policies of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V and his Flemish ministers.Padilla was the eldest son of the commendator of Castile...

, Juan Bravo, and Francisco Maldonado

Francisco Maldonado

Francisco Maldonado was a leader of the rebel Comuneros from Salamanca in the Revolt of the Comuneros.He was captured at the Battle of Villalar, and beheaded the following day....

. They were beheaded the next morning in the Plaza of Villalar, with a large portion of the royalist nobility present. The remains of the rebel army at Villalar fragmented, with some attempting to join Acuña's army near Toledo and others fleeing to Portugal.

Navarre

In early May, a large French/Navarrese army crossed the PyreneesPyrenees

The Pyrenees is a range of mountains in southwest Europe that forms a natural border between France and Spain...

and attacked the Spanish-occupied portion of Navarre. If the comuneros had held out slightly longer, it might have saved them, but by the time of the invasion the Battle of Villalar

Battle of Villalar

The Battle of Villalar was a battle in the Revolt of the Comuneros fought on April 23, 1521 near the town of Villalar in Valladolid province, Spain. The royalist supporters of King Charles I won a crushing victory over the comuneros rebels. Three of the most important rebel leaders were...

had already happened. Instead of an opportunity to win the war, the invasion instead became a way for former comunero cities nervous about potential reprisals to prove their loyalty by sending large contingents to fight the French and Navarrese. An even larger Castilian army attacked the French and crushingly defeated them at the Battle of Noáin

Battle of Noáin

The Battle of Noáin or the Battle of Esquiroz, fought on June 30 1521 was the only mayor battle in the Spanish conquest of Iberian Navarre. It was a decisive victory for the Spanish against the invading Franco-Navarrese army.- Prelude :...

on June 30, 1521.