Dag Hammarskjöld

Encyclopedia

Dag Hjalmar Agne Carl Hammarskjöld (29 July 1905 – 18 September 1961) was a Swedish diplomat

, economist

, and author

. An early Secretary-General of the United Nations, he served from April 1953 until his death in a plane crash in September 1961. He is the only person to have been awarded a posthumous Nobel Peace Prize

. Hammarskjöld remains the only U.N. Secretary-General to die in office, and his death occurred en route to cease-fire negotiations. President of the United States

John F. Kennedy

called Hammarskjöld “the greatest statesman of our century".

, Sweden, but spent most of his childhood in Uppsala

. The fourth and youngest son of Hjalmar Hammarskjöld

, Prime Minister of Sweden

from 1914 to 1917, and Agnes Hammarskjöld (née Almquist), Hammarskjöld's ancestors served the Monarchy of Sweden since the 17th century. He studied first at Katedralskolan

and then at Uppsala University

where he graduated with a Bachelor of Laws

and a Master's degree

in Political economy

. During this time he served for a year as the first Curator at Uplands Nation

later moving to Stockholm

.

From 1930 to 1934, Hammarskjöld was a Secretary on a governmental committee on unemployment

. During this time he wrote his economics thesis, "Konjunkturspridningen" ("The Spread of the Business Cycle"), and received a doctorate

from Stockholm University

. In 1936, he became a Secretary at the Sveriges Riksbank

and was soon promoted. From 1941 to 1948, he served as Chairman of the bank.

During this time Hammarskjöld also held political positions. Early in 1945, he was appointed an adviser to the cabinet on financial and economic problems. He helped coordinate government plans to alleviate the economic problems of the post-war period. In 1947, Hammarskjöld was appointed to a position with Sweden’s Ministry for Foreign Affairs

, and in 1949 he became the State Secretary for Foreign Affairs

. A delegate to the Paris conference that established the Marshall Plan

, in 1948 he was again in Paris to attend a conference for the Organisation for European Economic Co-operation

. In 1950, he became head of the Swedish delegation to UNISCAN. In 1951, he became a cabinet Minister without Portfolio

. Although Hammarskjöld served in a cabinet dominated by the Social Democrats

, he never officially joined any political party. In 1951, Hammarskjöld became Vice Chairman of the Swedish delegation to the United Nations General Assembly

in Paris. He became the Chairman of the Swedish delegation to the General Assembly in New York in 1952. On 20 December 1954, he was elected to take his father's vacated seat in the Swedish Academy

.

When Trygve Lie

When Trygve Lie

resigned from his post as UN Secretary-General in 1953, the United Nations Security Council

recommended Hammarskjöld for the post. It came as a surprise to him. Seen as a competent technocrat without political views, he was selected on 31 March by a majority of 10 out of eleven Security Council members. The UN General Assembly elected him in the 7–10 April session by 57 votes out of 60. In 1957, he was re-elected.

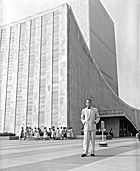

Hammarskjöld began his term by establishing his own secretariat of 4,000 administrators and setting up regulations that defined their responsibilities. He was also actively engaged in smaller projects relating to the UN working environment. For example, he planned and supervised in every detail the creation of a "meditation room" in the UN headquarters. This is a place dedicated to silence where people can withdraw into themselves, regardless of their faith, creed, or religion.

During his term, Hammarskjöld tried to smooth relations between Israel

and the Arab states. Other highlights include a 1955 visit to China

to negotiate release of 15 captured US pilots who had served in the Korean War

, the 1956 establishment of the United Nations Emergency Force

, and his intervention in the 1956 Suez Crisis

. He is given credit by some historians for allowing participation of the Holy See

within the United Nations that year.

In 1960, the former Belgian Congo

and then newly independent Congo

asked for UN aid in defusing the Congo Crisis

. Hammarskjöld made four trips to the Congo. His efforts towards the decolonisation of Africa were considered insufficient by the Soviet Union

; in September 1960, the Soviet government denounced his decision to send a UN emergency force to keep the peace. They demanded his resignation and the replacement of the office of Secretary-General by a three-man directorate with a built-in veto

, the "troika

". The objective was to, citing the memoirs of Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev

, “equally represent interests of three groups of countries: capitalist, socialist and recently independent.”

Hammarskjöld denied Patrice Lumumba

's request to help force the Katanga Province

to rejoin the Congo, causing Lumumba to turn to the Soviets for help. He personally disliked Lumumba and felt that he should be removed from office.

In September 1961, Hammarskjöld learned about fighting between "non-combatant" UN forces and Katangese

In September 1961, Hammarskjöld learned about fighting between "non-combatant" UN forces and Katangese

troops of Moise Tshombe

. He was en route to negotiate a cease-fire on the night of 17–18 September when his Douglas DC-6

airliner SE-BDY crashed near Ndola

, Northern Rhodesia

(now Zambia

). Hammarskjöld and fifteen others perished in the crash.

A special report issued by the United Nations following the crash stated that a bright flash in the sky was seen at approximately 1:00 am the previous night. According to the UN special report, it was this information that resulted in the initiation of search and rescue operations. Initial indications that the crash might not have been an accident led to multiple official inquiries and persistent speculation that the Secretary-General was assassinated.

Hammarskjöld's death was a memorable event. The Dag Hammarskjöld Crash Site Memorial

is under consideration for inclusion as a UNESCO

World Heritage Site. A press release issued by the Prime Minister of the Republic of the Congo stated that, "... in order to pay a tribute to this great man, now vanished from the scene, and to his colleagues, all of whom have fallen victim to the shameless intrigues of the great financial Powers of the West... the Government has decided to proclaim Tuesday, 19 September 1961, a day of national mourning."

The Rhodesian Board of Investigation looked into the matter between 19 September 1961 and 2 November 1961 under the command of British Lt. Colonel M.C.B. Barber. The Rhodesian Commission of Inquiry held hearings from 16–29 January 1962 without United Nations oversight. The subsequent United Nations Commission of Investigation held a series of hearings in 1962 and in part depended upon the testimony from the previous Rhodesian inquiries. Five "eminent persons" were assigned by the new Secretary-General to the UN Commission. The members of the commission unanimously elected Nepal

ese diplomat Rishikesh Shaha

to head an inquiry.

The three official inquiries failed to determine conclusively the cause of the crash that led to the death of Hammarskjöld. The Rhodesian Board of Investigation sent 180 men to search a six-square-kilometer area of the last sector of the aircraft's flight-path, looking for evidence as to the cause of the crash. No evidence of a bomb, surface-to-air missile

, or hijacking was found. The official report stated that two of the dead Swedish bodyguards had suffered multiple bullet wounds. Medical examination, performed by the initial Rhodesian Board of Investigation and reported in the UN official report, indicated that the wounds were superficial, and that the bullets showed no signs of rifling

. They concluded that the bullets exploded in the fire in close proximity to the bodyguards. No other evidence of foul play was found in the wreckage of the aircraft.

Previous accounts of a bright flash in the sky were dismissed as occurring too late in the evening to have caused the crash. The UN report speculated that these flashes may have been caused by secondary explosions after the crash. The sole survivor, Sergeant Harold Julien, indicated that there was a series of explosions that preceded the crash. The official inquiry found that the statements of witnesses who talked with Julien were inconsistent.

The report states that there were numerous delays that violated the established search and rescue procedures. There were three separate delays: the first delayed the initial alarm of a possible plane in trouble; the second delayed the "distress" alarm, which indicates that communications with surrounding airports indicate that a missing plane has not landed elsewhere; the third delayed the eventual search and rescue operation and the discovery of the plane wreckage, just miles away. The medical examiners report was inconclusive; one report said that Hammarskjöld had died on impact; another stated that Hammarskjöld might have survived had rescue operations not been delayed. The report also said that the chances of Sgt. Julien surviving the crash would have been "infinitely" better if the rescue operations had been hastened.

At the time of Hammarskjöld's death, Western intelligence agencies were actively involved in the political situation in the Congo, which culminated in Belgian and American support for the secession of Katanga

and the assassination of former prime minister Patrice Lumumba

. Belgium and the United Kingdom had a vested interest in maintaining their control over much of the country's copper industry during the Congolese transition from colonialism

to independence. Concerns about the nationalization of the copper industry could have provided a financial incentive to remove either Lumumba or Hammarskjöld. Belgium has since publicly acknowledged and apologized for its negligence in the death of Lumumba.

The involvement of British officers in commanding the initial inquiries, which provided much of the information about the condition of the plane and the examination of the bodies, has led some to suggest a conflict of interest. The official report dismissed a number of pieces of evidence that would have supported the view that Hammarskjöld was assassinated. Some of these dismissals have been controversial, such as the conclusion that bullet wounds could have been caused by bullets exploding in a fire. Expert tests have questioned this conclusion, arguing that exploding bullets could not break the surface of the skin. Major C. F. Westell, a ballistics authority, said, "I can certainly describe as sheer nonsense the statement that cartridges of machine guns or pistols detonated in a fire can penetrate a human body." He based his statement on a large scale experiment that had been done to determine if military fire brigades would be in danger working near munitions depots. Other Swedish experts conducted and filmed tests showing that bullets heated to the point of explosion nonetheless did not achieve sufficient velocity to penetrate their box container.

Sir Denis A H Wright, the then British Ambassador to Ethiopia

, in his annual report for 1961 establishes linkage of UN Secretary General Dag Hammarskjold’s death on 18 September to British refusal to allow an Ethiopian Military plane carrying troops destined to join the UN mission, landing at Entebbe

and over-flying British territory to Congo. Their refusal was only lifted after the death of the Secretary General. A Foreign Office official noting his comments on file, wrote affirming no “skeletons” in British cupboard and suggesting the Ambassador's comments should be removed from the final, official ‘printed’ version of the annual report.

On 19 August 1998, the Archbishop Desmond Tutu

, chairman of South Africa's Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), stated that recently uncovered letters had implicated the British MI5

, the American CIA, and then South African intelligence services in the crash. One TRC letter said that a bomb in the aircraft's wheel bay was set to detonate when the wheels came down for a landing. Tutu said that they were unable to investigate the truth of the letters or the allegations that South Africa or Western intelligence agencies played a role in the crash. The British Foreign Office suggested that they may have been created as Soviet misinformation

or disinformation

.

On 29 July 2005, the Norwegian Major General

, Bjørn Egge

, gave an interview to the newspaper Aftenposten

on the events surrounding Hammarskjöld's death. According to General Egge, who had been the first UN officer to see the body, Hammarskjöld had a hole in his forehead, and this hole was subsequently airbrush

ed from photos taken of the body. It appeared to Egge that Hammarskjöld had been thrown from the plane, and grass and leaves in his hands might indicate that he survived the crash – and that he had tried to scramble away from the wreckage. Egge does not claim directly that the wound was a gunshot wound.

In his speech to the 64th session of the United Nations General Assembly

on 23 September 2009, Colonel Gaddafi called upon the Libyan president of UNGA, Ali Treki, to institute a UN investigation into the assassination

s of Congolese prime minister, Patrice Lumumba

, who was overthrown in 1960 and murdered the following year, and of UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld in 1961.

According to a dozen witnesses interviewed by Swedish aid worker Göran Björkdahl in the 2000s, Hammarskjöld's plane was shot down by another aircraft. Björkdahl also reviewed previously unavailable archive documents and internal UN communcations. He believes that there was an intentional shootdown for the benefit of mining companies like Union Minière

. A US intelligence officer who was stationed at an electronic surveillance station in Cyprus

stated that he heard a cockpit recording from Ndola. In the cockpit recording a pilot talks of closing in on the DC6 in which Hammarskjold was traveling, guns are heard firing, and then the words "I've hit it," according to the US intelligence officer.

. In this talk he declared: "But the explanation of how man should live a life of active social service in full harmony with himself as a member of the community of spirit, I found in the writings of those great medieval mystics[ Meister Eckhart

and Jan van Ruysbroek] for whom 'self-surrender' had been the way to self-realization, and who in 'singleness of mind' and 'inwardness' had found strength to say yes to every demand which the needs of their neighbours made them face, and to say yes also to every fate life had in store for them when they followed the call of duty as they understood it."

His only book, Vägmärken

(Markings), was published in 1963. A collection of his diary reflections, the book starts in 1925, when he was 20 years old, and ends at his death in 1961. This diary was found in his New York house, after his death, along with an undated letter addressed to then Swedish Permanent Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs, Leif Belfrage. In this letter, Dag writes, "These entries provide the only true 'profile' that can be drawn ... If you find them worth publishing, you have my permission to do so". The foreword is written by W.H. Auden, a friend of Dag's. Markings was described by a theologian, the late Henry P. Van Dusen, as "the noblest self-disclosure of spiritual struggle and triumph, perhaps the greatest testament of personal faith written ... in the heat of professional life and amidst the most exacting responsibilities for world peace

and order." Hammarskjöld writes, for example, "We are not permitted to choose the frame of our destiny. But what we put into it is ours. He who wills adventure will experience it — according to the measure of his courage. He who wills sacrifice will be sacrificed — according to the measure of his purity of heart." Markings is characterised by Hammarskjöld's intermingling of prose and haiku

poetry in a manner exemplified by the 17th-century Japanese poet Basho

in his Narrow Roads to the Deep North. In his foreword to Markings, the English poet W. H. Auden

quotes Hammarskjöld as stating "In our age, the road to holiness necessarily passes through the world of action."

The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America commemorates the life of Hammarskjöld as a renewer of society on the anniversary of his death, September 18.

Diplomat

A diplomat is a person appointed by a state to conduct diplomacy with another state or international organization. The main functions of diplomats revolve around the representation and protection of the interests and nationals of the sending state, as well as the promotion of information and...

, economist

Economist

An economist is a professional in the social science discipline of economics. The individual may also study, develop, and apply theories and concepts from economics and write about economic policy...

, and author

Author

An author is broadly defined as "the person who originates or gives existence to anything" and that authorship determines responsibility for what is created. Narrowly defined, an author is the originator of any written work.-Legal significance:...

. An early Secretary-General of the United Nations, he served from April 1953 until his death in a plane crash in September 1961. He is the only person to have been awarded a posthumous Nobel Peace Prize

Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes bequeathed by the Swedish industrialist and inventor Alfred Nobel.-Background:According to Nobel's will, the Peace Prize shall be awarded to the person who...

. Hammarskjöld remains the only U.N. Secretary-General to die in office, and his death occurred en route to cease-fire negotiations. President of the United States

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

John F. Kennedy

John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald "Jack" Kennedy , often referred to by his initials JFK, was the 35th President of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963....

called Hammarskjöld “the greatest statesman of our century".

Early life

Dag Hammarskjöld was born in JönköpingJönköping

-Notable people:*Lillian Asplund, RMS Titanic survivor*John Bauer, illustrator, painter*Amy Diamond, singer*Agnetha Fältskog, ABBA*Carl Henrik Fredriksson, editor-in-chief and co-founder of Eurozine*Anders Gustafsson, kayaker, Olympian...

, Sweden, but spent most of his childhood in Uppsala

Uppsala

- Economy :Today Uppsala is well established in medical research and recognized for its leading position in biotechnology.*Abbott Medical Optics *GE Healthcare*Pfizer *Phadia, an offshoot of Pharmacia*Fresenius*Q-Med...

. The fourth and youngest son of Hjalmar Hammarskjöld

Hjalmar Hammarskjöld

Knut Hjalmar Leonard Hammarskjöld was a Swedish politician, scholar, cabinet minister, Member of Parliament from 1923 to 1938 , and Prime Minister of Sweden from 1914 to 1917....

, Prime Minister of Sweden

Prime Minister of Sweden

The Prime Minister is the head of government in the Kingdom of Sweden. Before the creation of the office of a Prime Minister in 1876, Sweden did not have a head of government separate from its head of state, namely the King, in whom the executive authority was vested...

from 1914 to 1917, and Agnes Hammarskjöld (née Almquist), Hammarskjöld's ancestors served the Monarchy of Sweden since the 17th century. He studied first at Katedralskolan

Katedralskolan, Uppsala

Katedralskolan is a school in Uppsala, Sweden. The school was established in 1246...

and then at Uppsala University

Uppsala University

Uppsala University is a research university in Uppsala, Sweden, and is the oldest university in Scandinavia, founded in 1477. It consistently ranks among the best universities in Northern Europe in international rankings and is generally considered one of the most prestigious institutions of...

where he graduated with a Bachelor of Laws

Bachelor of Laws

The Bachelor of Laws is an undergraduate, or bachelor, degree in law originating in England and offered in most common law countries as the primary law degree...

and a Master's degree

Master's degree

A master's is an academic degree granted to individuals who have undergone study demonstrating a mastery or high-order overview of a specific field of study or area of professional practice...

in Political economy

Political economy

Political economy originally was the term for studying production, buying, and selling, and their relations with law, custom, and government, as well as with the distribution of national income and wealth, including through the budget process. Political economy originated in moral philosophy...

. During this time he served for a year as the first Curator at Uplands Nation

Uplands nation

Uplands nation is a student society and one of thirteen nations at Uppsala University. It has traditionally recruited its members from the province of Uppland, which surrounds and includes Uppsala and stretches down south to the northern part of Stockholm. The nation uses an older spelling of the...

later moving to Stockholm

Stockholm

Stockholm is the capital and the largest city of Sweden and constitutes the most populated urban area in Scandinavia. Stockholm is the most populous city in Sweden, with a population of 851,155 in the municipality , 1.37 million in the urban area , and around 2.1 million in the metropolitan area...

.

From 1930 to 1934, Hammarskjöld was a Secretary on a governmental committee on unemployment

Unemployment

Unemployment , as defined by the International Labour Organization, occurs when people are without jobs and they have actively sought work within the past four weeks...

. During this time he wrote his economics thesis, "Konjunkturspridningen" ("The Spread of the Business Cycle"), and received a doctorate

Doctorate

A doctorate is an academic degree or professional degree that in most countries refers to a class of degrees which qualify the holder to teach in a specific field, A doctorate is an academic degree or professional degree that in most countries refers to a class of degrees which qualify the holder...

from Stockholm University

Stockholm University

Stockholm University is a state university in Stockholm, Sweden. It has over 28,000 students at four faculties, making it one of the largest universities in Scandinavia. The institution is also frequently regarded as one of the top 100 universities in the world...

. In 1936, he became a Secretary at the Sveriges Riksbank

Sveriges Riksbank

Sveriges Riksbank, or simply Riksbanken, is the central bank of Sweden and the world's oldest central bank. It is sometimes called the Swedish National Bank or the Bank of Sweden .-History:...

and was soon promoted. From 1941 to 1948, he served as Chairman of the bank.

During this time Hammarskjöld also held political positions. Early in 1945, he was appointed an adviser to the cabinet on financial and economic problems. He helped coordinate government plans to alleviate the economic problems of the post-war period. In 1947, Hammarskjöld was appointed to a position with Sweden’s Ministry for Foreign Affairs

Ministry for Foreign Affairs (Sweden)

The Ministry for Foreign Affairs is responsible for Swedish foreign policy.Current ministers:*Carl Bildt Head of Office and Minister for Foreign Affairs.*Ewa Björling as Minister for Foreign Trade...

, and in 1949 he became the State Secretary for Foreign Affairs

State Secretary for Foreign Affairs (Sweden)

The State Secretary for Foreign Affairs is the highest position below the rank of cabinet minister at the Swedish Ministry for Foreign Affairs. , Frank Belfrage is State Secretary....

. A delegate to the Paris conference that established the Marshall Plan

Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan was the large-scale American program to aid Europe where the United States gave monetary support to help rebuild European economies after the end of World War II in order to combat the spread of Soviet communism. The plan was in operation for four years beginning in April 1948...

, in 1948 he was again in Paris to attend a conference for the Organisation for European Economic Co-operation

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development is an international economic organisation of 34 countries founded in 1961 to stimulate economic progress and world trade...

. In 1950, he became head of the Swedish delegation to UNISCAN. In 1951, he became a cabinet Minister without Portfolio

Minister without Portfolio

A minister without portfolio is either a government minister with no specific responsibilities or a minister that does not head a particular ministry...

. Although Hammarskjöld served in a cabinet dominated by the Social Democrats

Swedish Social Democratic Party

The Swedish Social Democratic Workers' Party, , contesting elections as 'the Workers' Party – the Social Democrats' , or sometimes referred to just as 'the Social Democrats' and most commonly as Sossarna ; is the oldest and largest political party in Sweden. The party was founded in 1889...

, he never officially joined any political party. In 1951, Hammarskjöld became Vice Chairman of the Swedish delegation to the United Nations General Assembly

United Nations General Assembly

For two articles dealing with membership in the General Assembly, see:* General Assembly members* General Assembly observersThe United Nations General Assembly is one of the five principal organs of the United Nations and the only one in which all member nations have equal representation...

in Paris. He became the Chairman of the Swedish delegation to the General Assembly in New York in 1952. On 20 December 1954, he was elected to take his father's vacated seat in the Swedish Academy

Swedish Academy

The Swedish Academy , founded in 1786 by King Gustav III, is one of the Royal Academies of Sweden.-History:The Swedish Academy was founded in 1786 by King Gustav III. Modelled after the Académie française, it has 18 members. The motto of the Academy is "Talent and Taste"...

.

UN Secretary-General

Trygve Lie

Trygve Halvdan Lie was a Norwegian politician, labour leader, government official and author. He served as Norwegian Foreign minister during the critical years of the Norwegian government in exile in London from 1940 to 1945. From 1946 to 1952 he was the first Secretary-General of the United...

resigned from his post as UN Secretary-General in 1953, the United Nations Security Council

United Nations Security Council

The United Nations Security Council is one of the principal organs of the United Nations and is charged with the maintenance of international peace and security. Its powers, outlined in the United Nations Charter, include the establishment of peacekeeping operations, the establishment of...

recommended Hammarskjöld for the post. It came as a surprise to him. Seen as a competent technocrat without political views, he was selected on 31 March by a majority of 10 out of eleven Security Council members. The UN General Assembly elected him in the 7–10 April session by 57 votes out of 60. In 1957, he was re-elected.

Hammarskjöld began his term by establishing his own secretariat of 4,000 administrators and setting up regulations that defined their responsibilities. He was also actively engaged in smaller projects relating to the UN working environment. For example, he planned and supervised in every detail the creation of a "meditation room" in the UN headquarters. This is a place dedicated to silence where people can withdraw into themselves, regardless of their faith, creed, or religion.

During his term, Hammarskjöld tried to smooth relations between Israel

Israel

The State of Israel is a parliamentary republic located in the Middle East, along the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea...

and the Arab states. Other highlights include a 1955 visit to China

People's Republic of China

China , officially the People's Republic of China , is the most populous country in the world, with over 1.3 billion citizens. Located in East Asia, the country covers approximately 9.6 million square kilometres...

to negotiate release of 15 captured US pilots who had served in the Korean War

Korean War

The Korean War was a conventional war between South Korea, supported by the United Nations, and North Korea, supported by the People's Republic of China , with military material aid from the Soviet Union...

, the 1956 establishment of the United Nations Emergency Force

United Nations Emergency Force

The first United Nations Emergency Force was established by United Nations General Assembly to secure an end to the 1956 Suez Crisis with resolution 1001 on November 7, 1956. The force was developed in large measure as a result of efforts by UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld and a proposal...

, and his intervention in the 1956 Suez Crisis

Suez Crisis

The Suez Crisis, also referred to as the Tripartite Aggression, Suez War was an offensive war fought by France, the United Kingdom, and Israel against Egypt beginning on 29 October 1956. Less than a day after Israel invaded Egypt, Britain and France issued a joint ultimatum to Egypt and Israel,...

. He is given credit by some historians for allowing participation of the Holy See

Holy See

The Holy See is the episcopal jurisdiction of the Catholic Church in Rome, in which its Bishop is commonly known as the Pope. It is the preeminent episcopal see of the Catholic Church, forming the central government of the Church. As such, diplomatically, and in other spheres the Holy See acts and...

within the United Nations that year.

In 1960, the former Belgian Congo

Belgian Congo

The Belgian Congo was the formal title of present-day Democratic Republic of the Congo between King Leopold II's formal relinquishment of his personal control over the state to Belgium on 15 November 1908, and Congolese independence on 30 June 1960.-Congo Free State, 1884–1908:Until the latter...

and then newly independent Congo

Democratic Republic of the Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is a state located in Central Africa. It is the second largest country in Africa by area and the eleventh largest in the world...

asked for UN aid in defusing the Congo Crisis

Congo Crisis

The Congo Crisis was a period of turmoil in the First Republic of the Congo that began with national independence from Belgium and ended with the seizing of power by Joseph Mobutu...

. Hammarskjöld made four trips to the Congo. His efforts towards the decolonisation of Africa were considered insufficient by the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

; in September 1960, the Soviet government denounced his decision to send a UN emergency force to keep the peace. They demanded his resignation and the replacement of the office of Secretary-General by a three-man directorate with a built-in veto

Veto

A veto, Latin for "I forbid", is the power of an officer of the state to unilaterally stop an official action, especially enactment of a piece of legislation...

, the "troika

Troika (triumvirate)

Troika is a committee consisting of three members. The origin of "troika" comes from the term in Russian used to describe three-horse harnessed carriage, or more often, horse-drawn sledge.- Communist states :...

". The objective was to, citing the memoirs of Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev led the Soviet Union during part of the Cold War. He served as First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964, and as Chairman of the Council of Ministers, or Premier, from 1958 to 1964...

, “equally represent interests of three groups of countries: capitalist, socialist and recently independent.”

Hammarskjöld denied Patrice Lumumba

Patrice Lumumba

Patrice Émery Lumumba was a Congolese independence leader and the first legally elected Prime Minister of the Republic of the Congo after he helped win its independence from Belgium in June 1960. Only ten weeks later, Lumumba's government was deposed in a coup during the Congo Crisis...

's request to help force the Katanga Province

Katanga Province

Katanga Province is one of the provinces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Between 1971 and 1997, its official name was Shaba Province. Under the new constitution, the province was to be replaced by four smaller provinces by February 2009; this did not actually take place.Katanga's regional...

to rejoin the Congo, causing Lumumba to turn to the Soviets for help. He personally disliked Lumumba and felt that he should be removed from office.

Death

State of Katanga

Katanga was a breakaway state proclaimed on 11 July 1960 separating itself from the newly independent Democratic Republic of the Congo. In revolt against the new government of Patrice Lumumba in July, Katanga declared independence under Moise Tshombe, leader of the local CONAKAT party...

troops of Moise Tshombe

Moise Tshombe

Moïse Kapenda Tshombe was a Congolese politician.- Biography :He was the son of a successful Congolese businessman and was born in Musumba, Congo. He received his education from an American missionary school and later trained as an accountant...

. He was en route to negotiate a cease-fire on the night of 17–18 September when his Douglas DC-6

Douglas DC-6

The Douglas DC-6 is a piston-powered airliner and transport aircraft built by the Douglas Aircraft Company from 1946 to 1958. Originally intended as a military transport near the end of World War II, it was reworked after the war to compete with the Lockheed Constellation in the long-range...

airliner SE-BDY crashed near Ndola

Ndola

Ndola is the third largest city in Zambia, with a population of 495,000 . It is the industrial, commercial, on the Copperbelt, Zambia's copper-mining region, and capital of Copperbelt Province. It is also the commercial capital city of Zambia and has one of the three international airports, others...

, Northern Rhodesia

Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland

The Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, also known as the Central African Federation , was a semi-independent state in southern Africa that existed from 1953 to the end of 1963, comprising the former self-governing colony of Southern Rhodesia and the British protectorates of Northern Rhodesia,...

(now Zambia

Zambia

Zambia , officially the Republic of Zambia, is a landlocked country in Southern Africa. The neighbouring countries are the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the north, Tanzania to the north-east, Malawi to the east, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Botswana and Namibia to the south, and Angola to the west....

). Hammarskjöld and fifteen others perished in the crash.

A special report issued by the United Nations following the crash stated that a bright flash in the sky was seen at approximately 1:00 am the previous night. According to the UN special report, it was this information that resulted in the initiation of search and rescue operations. Initial indications that the crash might not have been an accident led to multiple official inquiries and persistent speculation that the Secretary-General was assassinated.

Hammarskjöld's death was a memorable event. The Dag Hammarskjöld Crash Site Memorial

Dag Hammarskjöld Crash Site Memorial

The Dag Hammarskjöld Memorial Crash Site marks the place of the plane crash in which Dag Hammarskjöld, the second and then-incumbent United Nations Secretary General was killed on the 17th September, 1961, while on a mission to the Congo Republic...

is under consideration for inclusion as a UNESCO

UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations...

World Heritage Site. A press release issued by the Prime Minister of the Republic of the Congo stated that, "... in order to pay a tribute to this great man, now vanished from the scene, and to his colleagues, all of whom have fallen victim to the shameless intrigues of the great financial Powers of the West... the Government has decided to proclaim Tuesday, 19 September 1961, a day of national mourning."

Official inquiry

Following the death of Hammarskjöld, there were three inquiries into the circumstances that led to the crash: the Rhodesian Board of Investigation, the Rhodesian Commission of Inquiry, and the United Nations Commission of Investigation.The Rhodesian Board of Investigation looked into the matter between 19 September 1961 and 2 November 1961 under the command of British Lt. Colonel M.C.B. Barber. The Rhodesian Commission of Inquiry held hearings from 16–29 January 1962 without United Nations oversight. The subsequent United Nations Commission of Investigation held a series of hearings in 1962 and in part depended upon the testimony from the previous Rhodesian inquiries. Five "eminent persons" were assigned by the new Secretary-General to the UN Commission. The members of the commission unanimously elected Nepal

Nepal

Nepal , officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal, is a landlocked sovereign state located in South Asia. It is located in the Himalayas and bordered to the north by the People's Republic of China, and to the south, east, and west by the Republic of India...

ese diplomat Rishikesh Shaha

Rishikesh Shaha

Rishikesh Shaha was a Nepalese writer, politician and human rights activist.-Political career:Shaha was a member of Nepal Prajatantrik Party 1948-1949. 1951-1953 he was the general secretary of Nepali Rastriya Congress. He then became general secretary of the joint Nepali Congress-Nepali Rashtriya...

to head an inquiry.

The three official inquiries failed to determine conclusively the cause of the crash that led to the death of Hammarskjöld. The Rhodesian Board of Investigation sent 180 men to search a six-square-kilometer area of the last sector of the aircraft's flight-path, looking for evidence as to the cause of the crash. No evidence of a bomb, surface-to-air missile

Surface-to-air missile

A surface-to-air missile or ground-to-air missile is a missile designed to be launched from the ground to destroy aircraft or other missiles...

, or hijacking was found. The official report stated that two of the dead Swedish bodyguards had suffered multiple bullet wounds. Medical examination, performed by the initial Rhodesian Board of Investigation and reported in the UN official report, indicated that the wounds were superficial, and that the bullets showed no signs of rifling

Rifling

Rifling is the process of making helical grooves in the barrel of a gun or firearm, which imparts a spin to a projectile around its long axis...

. They concluded that the bullets exploded in the fire in close proximity to the bodyguards. No other evidence of foul play was found in the wreckage of the aircraft.

Previous accounts of a bright flash in the sky were dismissed as occurring too late in the evening to have caused the crash. The UN report speculated that these flashes may have been caused by secondary explosions after the crash. The sole survivor, Sergeant Harold Julien, indicated that there was a series of explosions that preceded the crash. The official inquiry found that the statements of witnesses who talked with Julien were inconsistent.

The report states that there were numerous delays that violated the established search and rescue procedures. There were three separate delays: the first delayed the initial alarm of a possible plane in trouble; the second delayed the "distress" alarm, which indicates that communications with surrounding airports indicate that a missing plane has not landed elsewhere; the third delayed the eventual search and rescue operation and the discovery of the plane wreckage, just miles away. The medical examiners report was inconclusive; one report said that Hammarskjöld had died on impact; another stated that Hammarskjöld might have survived had rescue operations not been delayed. The report also said that the chances of Sgt. Julien surviving the crash would have been "infinitely" better if the rescue operations had been hastened.

Alternative theories

Despite the multiple official inquiries that failed to find evidence of assassination, some continue to believe that the death of Hammarskjöld was not an accident.At the time of Hammarskjöld's death, Western intelligence agencies were actively involved in the political situation in the Congo, which culminated in Belgian and American support for the secession of Katanga

State of Katanga

Katanga was a breakaway state proclaimed on 11 July 1960 separating itself from the newly independent Democratic Republic of the Congo. In revolt against the new government of Patrice Lumumba in July, Katanga declared independence under Moise Tshombe, leader of the local CONAKAT party...

and the assassination of former prime minister Patrice Lumumba

Patrice Lumumba

Patrice Émery Lumumba was a Congolese independence leader and the first legally elected Prime Minister of the Republic of the Congo after he helped win its independence from Belgium in June 1960. Only ten weeks later, Lumumba's government was deposed in a coup during the Congo Crisis...

. Belgium and the United Kingdom had a vested interest in maintaining their control over much of the country's copper industry during the Congolese transition from colonialism

Colonialism

Colonialism is the establishment, maintenance, acquisition and expansion of colonies in one territory by people from another territory. It is a process whereby the metropole claims sovereignty over the colony and the social structure, government, and economics of the colony are changed by...

to independence. Concerns about the nationalization of the copper industry could have provided a financial incentive to remove either Lumumba or Hammarskjöld. Belgium has since publicly acknowledged and apologized for its negligence in the death of Lumumba.

The involvement of British officers in commanding the initial inquiries, which provided much of the information about the condition of the plane and the examination of the bodies, has led some to suggest a conflict of interest. The official report dismissed a number of pieces of evidence that would have supported the view that Hammarskjöld was assassinated. Some of these dismissals have been controversial, such as the conclusion that bullet wounds could have been caused by bullets exploding in a fire. Expert tests have questioned this conclusion, arguing that exploding bullets could not break the surface of the skin. Major C. F. Westell, a ballistics authority, said, "I can certainly describe as sheer nonsense the statement that cartridges of machine guns or pistols detonated in a fire can penetrate a human body." He based his statement on a large scale experiment that had been done to determine if military fire brigades would be in danger working near munitions depots. Other Swedish experts conducted and filmed tests showing that bullets heated to the point of explosion nonetheless did not achieve sufficient velocity to penetrate their box container.

Sir Denis A H Wright, the then British Ambassador to Ethiopia

Ethiopia

Ethiopia , officially known as the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a country located in the Horn of Africa. It is the second-most populous nation in Africa, with over 82 million inhabitants, and the tenth-largest by area, occupying 1,100,000 km2...

, in his annual report for 1961 establishes linkage of UN Secretary General Dag Hammarskjold’s death on 18 September to British refusal to allow an Ethiopian Military plane carrying troops destined to join the UN mission, landing at Entebbe

Entebbe

Entebbe is a major town in Central Uganda. Located on a Lake Victoria peninsula, the town was at one time, the seat of government for the Protectorate of Uganda, prior to Independence in 1962...

and over-flying British territory to Congo. Their refusal was only lifted after the death of the Secretary General. A Foreign Office official noting his comments on file, wrote affirming no “skeletons” in British cupboard and suggesting the Ambassador's comments should be removed from the final, official ‘printed’ version of the annual report.

On 19 August 1998, the Archbishop Desmond Tutu

Desmond Tutu

Desmond Mpilo Tutu is a South African activist and retired Anglican bishop who rose to worldwide fame during the 1980s as an opponent of apartheid...

, chairman of South Africa's Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), stated that recently uncovered letters had implicated the British MI5

MI5

The Security Service, commonly known as MI5 , is the United Kingdom's internal counter-intelligence and security agency and is part of its core intelligence machinery alongside the Secret Intelligence Service focused on foreign threats, Government Communications Headquarters and the Defence...

, the American CIA, and then South African intelligence services in the crash. One TRC letter said that a bomb in the aircraft's wheel bay was set to detonate when the wheels came down for a landing. Tutu said that they were unable to investigate the truth of the letters or the allegations that South Africa or Western intelligence agencies played a role in the crash. The British Foreign Office suggested that they may have been created as Soviet misinformation

Misinformation

Misinformation is false or inaccurate information that is spread unintentionally. It is distinguished from disinformation by motive in that misinformation is simply erroneous, while disinformation, in contrast, is intended to mislead....

or disinformation

Disinformation

Disinformation is intentionally false or inaccurate information that is spread deliberately. For this reason, it is synonymous with and sometimes called black propaganda. It is an act of deception and false statements to convince someone of untruth...

.

On 29 July 2005, the Norwegian Major General

Major General

Major general or major-general is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. A major general is a high-ranking officer, normally subordinate to the rank of lieutenant general and senior to the ranks of brigadier and brigadier general...

, Bjørn Egge

Bjørn Egge

Bjørn Egge CBE was a retired Major General of the Norwegian Defence Force.Egge was a soldier during the German attack on Norway in 1940...

, gave an interview to the newspaper Aftenposten

Aftenposten

Aftenposten is Norway's largest newspaper. It retook this position in 2010, taking it from the tabloid Verdens Gang which had been the largest newspaper for several decades. It is based in Oslo. The morning edition, which is distributed across all of Norway, had a circulation of 250,179 in 2007...

on the events surrounding Hammarskjöld's death. According to General Egge, who had been the first UN officer to see the body, Hammarskjöld had a hole in his forehead, and this hole was subsequently airbrush

Airbrush

An airbrush is a small, air-operated tool that sprays various media including ink and dye, but most often paint by a process of nebulization. Spray guns developed from the airbrush and are still considered a type of airbrush.-History:...

ed from photos taken of the body. It appeared to Egge that Hammarskjöld had been thrown from the plane, and grass and leaves in his hands might indicate that he survived the crash – and that he had tried to scramble away from the wreckage. Egge does not claim directly that the wound was a gunshot wound.

In his speech to the 64th session of the United Nations General Assembly

United Nations General Assembly

For two articles dealing with membership in the General Assembly, see:* General Assembly members* General Assembly observersThe United Nations General Assembly is one of the five principal organs of the United Nations and the only one in which all member nations have equal representation...

on 23 September 2009, Colonel Gaddafi called upon the Libyan president of UNGA, Ali Treki, to institute a UN investigation into the assassination

Assassination

To carry out an assassination is "to murder by a sudden and/or secret attack, often for political reasons." Alternatively, assassination may be defined as "the act of deliberately killing someone, especially a public figure, usually for hire or for political reasons."An assassination may be...

s of Congolese prime minister, Patrice Lumumba

Patrice Lumumba

Patrice Émery Lumumba was a Congolese independence leader and the first legally elected Prime Minister of the Republic of the Congo after he helped win its independence from Belgium in June 1960. Only ten weeks later, Lumumba's government was deposed in a coup during the Congo Crisis...

, who was overthrown in 1960 and murdered the following year, and of UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld in 1961.

According to a dozen witnesses interviewed by Swedish aid worker Göran Björkdahl in the 2000s, Hammarskjöld's plane was shot down by another aircraft. Björkdahl also reviewed previously unavailable archive documents and internal UN communcations. He believes that there was an intentional shootdown for the benefit of mining companies like Union Minière

Union Minière du Haut Katanga

The Union Minière du Haut Katanga was a Belgian mining company, once operating in Katanga, in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo...

. A US intelligence officer who was stationed at an electronic surveillance station in Cyprus

Cyprus

Cyprus , officially the Republic of Cyprus , is a Eurasian island country, member of the European Union, in the Eastern Mediterranean, east of Greece, south of Turkey, west of Syria and north of Egypt. It is the third largest island in the Mediterranean Sea.The earliest known human activity on the...

stated that he heard a cockpit recording from Ndola. In the cockpit recording a pilot talks of closing in on the DC6 in which Hammarskjold was traveling, guns are heard firing, and then the words "I've hit it," according to the US intelligence officer.

Honors

- Hammarskjöld posthumously received the Nobel Peace PrizeNobel Peace PrizeThe Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes bequeathed by the Swedish industrialist and inventor Alfred Nobel.-Background:According to Nobel's will, the Peace Prize shall be awarded to the person who...

in 1961, having been nominated before his death. - Honorary degrees: The Carleton UniversityCarleton UniversityCarleton University is a comprehensive university located in the capital of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario. The enabling legislation is The Carleton University Act, 1952, S.O. 1952. Founded as a small college in 1942, Carleton now offers over 65 programs in a diverse range of disciplines. Carleton has...

in OttawaOttawaOttawa is the capital of Canada, the second largest city in the Province of Ontario, and the fourth largest city in the country. The city is located on the south bank of the Ottawa River in the eastern portion of Southern Ontario...

(then called Carleton College) awarded its first-ever honorary degree to Hammarskjöld in 1954 when it presented him with a Legum DoctorLegum DoctorLegum Doctor is a doctorate-level academic degree in law, or an honorary doctorate, depending on the jurisdiction. The double L in the abbreviation refers to the early practice in the University of Cambridge to teach both Canon Law and Civil Law, the double L indicating the plural, Doctor of both...

, honoris causa. The University has continued this tradition by conferring an honorary doctorate upon every subsequent Secretary General of the United Nations. He also held honorary degrees from Oxford University, England; in the United States from Harvard, YaleYALERapidMiner, formerly YALE , is an environment for machine learning, data mining, text mining, predictive analytics, and business analytics. It is used for research, education, training, rapid prototyping, application development, and industrial applications...

, PrincetonPrinceton UniversityPrinceton University is a private research university located in Princeton, New Jersey, United States. The school is one of the eight universities of the Ivy League, and is one of the nine Colonial Colleges founded before the American Revolution....

, ColumbiaColumbia UniversityColumbia University in the City of New York is a private, Ivy League university in Manhattan, New York City. Columbia is the oldest institution of higher learning in the state of New York, the fifth oldest in the United States, and one of the country's nine Colonial Colleges founded before the...

, the University of PennsylvaniaUniversity of PennsylvaniaThe University of Pennsylvania is a private, Ivy League university located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States. Penn is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States,Penn is the fourth-oldest using the founding dates claimed by each institution...

, AmherstAmherst CollegeAmherst College is a private liberal arts college located in Amherst, Massachusetts, United States. Amherst is an exclusively undergraduate four-year institution and enrolled 1,744 students in the fall of 2009...

, Johns HopkinsJohns HopkinsJohns Hopkins was a wealthy American entrepreneur, philanthropist and abolitionist of 19th-century Baltimore, Maryland, now most noted for his philanthropic creation of the institutions that bear his name, namely the Johns Hopkins Hospital, and the Johns Hopkins University and its associated...

, the University of CaliforniaUniversity of CaliforniaThe University of California is a public university system in the U.S. state of California. Under the California Master Plan for Higher Education, the University of California is a part of the state's three-tier public higher education system, which also includes the California State University...

, and Ohio UniversityOhio UniversityOhio University is a public university located in the Midwestern United States in Athens, Ohio, situated on an campus...

; in Sweden, Uppsala University; and in Canada from McGill UniversityMcGill UniversityMohammed Fathy is a public research university located in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. The university bears the name of James McGill, a prominent Montreal merchant from Glasgow, Scotland, whose bequest formed the beginning of the university...

as well as Carleton. - On April 6, 2011, the Bank of Sweden announced that Hammarskjöld's image will be used on the 1000 kronorSwedish kronaThe krona has been the currency of Sweden since 1873. Both the ISO code "SEK" and currency sign "kr" are in common use; the former precedes or follows the value, the latter usually follows it, but especially in the past, it sometimes preceded the value...

banknote, the highest-denomination banknote in Sweden.

Legacy

- John F. KennedyJohn F. KennedyJohn Fitzgerald "Jack" Kennedy , often referred to by his initials JFK, was the 35th President of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963....

: After Hammarskjöld's death, U.S. President John F. Kennedy regretted that he opposed the UN policy in the Congo and said: “I realise now that in comparison to him, I am a small man. He was the greatest statesman of our century.” - Refusal to resign: One of Hammarskjöld's greatest moments was refusing to give in to Soviet pressure to resign. Dag Hammarskjöld: "It is very easy to bow to the wish of a big power. It is another matter to resist it. If it is the wish of those nations who see the organization their best protection in the present world, I shall do so again."

- In 2011 The Financial Times reported that Hammarskjöld has remained the benchmark against which later UN Secretary-Generals have been judged.

- Historians' views:

- Historian Paul KennedyPaul KennedyPaul Michael Kennedy CBE, FBA , is a British historian at Yale University specialising in the history of international relations, economic power and grand strategy. He has published prominent books on the history of British foreign policy and Great Power struggles...

hailed Hammarskjöld in his book The Parliament of Man as perhaps the greatest UN Secretary-General because of his ability to shape events, in contrast with his successors. - In contrast, the right-wing writer Paul Johnson in A History of the Modern World from 1917 to the 1980s (1983) was highly critical of his judgment.

- Historian Paul Kennedy

- Libraries:

- The Dag Hammarskjöld LibraryDag Hammarskjöld LibraryThe Dag Hammarskjöld Library is part of the United Nations headquarters and is connected to the Secretariat and conference buildings through ground level and underground corridors. It is named after Dag Hammarskjöld, the second Secretary-General of the United Nations.The Library has specialized in...

, a part of the United Nations headquartersUnited Nations headquartersThe headquarters of the United Nations is a complex in New York City. The complex has served as the official headquarters of the United Nations since its completion in 1952. It is located in the Turtle Bay neighborhood of Manhattan, on spacious grounds overlooking the East River...

, was dedicated on 16 November 1961 in honour of the late Secretary-General. - Uppsala University: There is also a Dag Hammarskjöld Library at his alma mater, Uppsala University.

- The Dag Hammarskjöld Library

- Buildings and rooms:

- Columbia UniversityColumbia UniversityColumbia University in the City of New York is a private, Ivy League university in Manhattan, New York City. Columbia is the oldest institution of higher learning in the state of New York, the fifth oldest in the United States, and one of the country's nine Colonial Colleges founded before the...

: The School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University in New York has a Dag Hammarskjöld Lounge. The graduate school is dedicated to the principles of international peace and cooperation that Hammarskjöld embodied. - Stanford UniversityStanford UniversityThe Leland Stanford Junior University, commonly referred to as Stanford University or Stanford, is a private research university on an campus located near Palo Alto, California. It is situated in the northwestern Santa Clara Valley on the San Francisco Peninsula, approximately northwest of San...

: Dag Hammarskjöld House on the Stanford University campus is a residence cooperative for undergraduate and graduate students with international backgrounds and interests at Stanford. - The Geneva School of Diplomacy and International Relations in Geneva, Switzerland has a room named after him.

- Dag Hammarskjöld StadiumDag Hammarskjöld StadiumDag Hammarskjöld Stadium was a multi-use stadium in Ndola, Zambia, named after former Secretary-General of the United Nations Dag Hammarskjöld. It was used mostly for football matches and served as the home for ZESCO United Football Club. The stadium had a capacity of 18,000 people. In 1988 the...

is the main football stadium of NdolaNdolaNdola is the third largest city in Zambia, with a population of 495,000 . It is the industrial, commercial, on the Copperbelt, Zambia's copper-mining region, and capital of Copperbelt Province. It is also the commercial capital city of Zambia and has one of the three international airports, others...

, ZambiaZambiaZambia , officially the Republic of Zambia, is a landlocked country in Southern Africa. The neighbouring countries are the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the north, Tanzania to the north-east, Malawi to the east, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Botswana and Namibia to the south, and Angola to the west....

. Hammarskjold's ill-fated flight in 1961 crashed in the outskirts of Ndola.

- Columbia University

- Streets:

- Dag Hammarskjölds Gade is a street in AalborgAalborg-Transport:On the north side of the Limfjord is Nørresundby, which is connected to Aalborg by a road bridge Limfjordsbroen, an iron railway bridge Jernbanebroen over Limfjorden, as well as a motorway tunnel running under the Limfjord Limfjordstunnelen....

, Denmark - Dag Hammarskjölds Väg is one of the longest streets in Uppsala, Sweden. There are several other streets in Sweden sharing this name.

- Dag Hammarskjöld's AlléAvenue (landscape)__notoc__In landscaping, an avenue or allée is traditionally a straight route with a line of trees or large shrubs running along each, which is used, as its French source venir indicates, to emphasize the "coming to," or arrival at a landscape or architectural feature...

is a street in CopenhagenCopenhagenCopenhagen is the capital and largest city of Denmark, with an urban population of 1,199,224 and a metropolitan population of 1,930,260 . With the completion of the transnational Øresund Bridge in 2000, Copenhagen has become the centre of the increasingly integrating Øresund Region...

, Denmark. - The headquarters of the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the CaribbeanUnited Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the CaribbeanThe United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean was established in 1948 to encourage economic cooperation among its member states. In 1984, a resolution was passed to include the countries of the Caribbean in the name...

(CEPAL) in SantiagoSantiago, ChileSantiago , also known as Santiago de Chile, is the capital and largest city of Chile, and the center of its largest conurbation . It is located in the country's central valley, at an elevation of above mean sea level...

, ChileChileChile ,officially the Republic of Chile , is a country in South America occupying a long, narrow coastal strip between the Andes mountains to the east and the Pacific Ocean to the west. It borders Peru to the north, Bolivia to the northeast, Argentina to the east, and the Drake Passage in the far...

lies on Avenida Dag Hammarskjöld. - The headquarters of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (German Society for International Cooperation, GIZ), is on Dag-Hammarskjöld-Weg in EschbornEschbornEschborn is a town near Frankfurt am Main in the Main-Taunus district, Hesse, Germany. As of 2009, it had a population of 20,789, but boasts fulltime employment of over 30,000 people...

, Germany. - Dag Hammarskjöldlaan is a street in the town of CastricumCastricumCastricum is a municipality and a town in the Netherlands, in the province of North Holland.Castricum is a tourist attraction in the province North Holland...

, The Netherlands.

- Dag Hammarskjölds Gade is a street in Aalborg

- New York City: A ManhattanManhattanManhattan is the oldest and the most densely populated of the five boroughs of New York City. Located primarily on the island of Manhattan at the mouth of the Hudson River, the boundaries of the borough are identical to those of New York County, an original county of the state of New York...

park near the United Nations headquarters is called the Dag Hammarskjold Plaza, as are several of the surrounding office buildings. - Religious commemoration: He is also commemorated as a peacemaker in the Calendar of SaintsCalendar of Saints (Lutheran)The Lutheran Calendar of Saints is a listing which details the primary annual festivals and events that are celebrated liturgically by some Lutheran Churches in the United States. The calendars of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America and the Lutheran Church - Missouri Synod are from the...

of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in AmericaEvangelical Lutheran Church in AmericaThe Evangelical Lutheran Church in America is a mainline Protestant denomination headquartered in Chicago, Illinois. The ELCA officially came into existence on January 1, 1988, by the merging of three churches. As of December 31, 2009, it had 4,543,037 baptized members, with 2,527,941 of them...

on 18 September of each year. - Schools: A number of schools have been named after Hammarskjöld, including Hammarskjold Middle SchoolHammarskjold Middle SchoolHammarskjold Middle School is a middle school for grades 6 and 7 in East Brunswick Township, New Jersey, as part of the East Brunswick Public Schools...

in East Brunswick Township, New JerseyEast Brunswick Township, New JerseyThe town is located southwest of New York City and 48 miles northeast of Philadelphia.Lawrence Brook, a tributary of the Raritan River, runs along the western border of the township...

; Dag Hammarskjold Middle SchoolDag Hammarskjold Middle SchoolDag Hammarskjold Middle School, generally referred to as Dag, is a New Haven County public middle school located on the east side of Wallingford, Connecticut, next to the Lyman Hall High School campus. Dag is part of the Wallingford Public Schools district. It is one of two public middle schools in...

in Wallingford, ConnecticutWallingford, ConnecticutWallingford is a town in New Haven County, Connecticut, United States. The population was 43,026 at the 2000 census.- History :Wallingford was established on October 10, 1667, when the Connecticut General Assembly authorized the "making of a village on the east river" to 38 planters and freemen...

; Dag Hammarskjold Elementary SchoolDag Hammarskjold Elementary SchoolDag Hammarskjold Elementary School is a part of the Parma City School District. It is located in Parma, Ohio. It was built in 1968, sits on , is , and has 22 classrooms. It is the newest elementary school in the school district. The school was named after Dag Hammarskjöld, who was the second...

in Parma, OhioParma, OhioParma is a city in Cuyahoga County, Ohio, United States. It is the largest suburb of Cleveland and the seventh largest city in the state of Ohio...

; Dag Hammarskjold Elementary (PS 254) in Brooklyn, New York; and Hammarskjold High SchoolHammarskjold High SchoolHammarskjold High School is a public high school located in Thunder Bay, Ontario, Canada, with an enrollment of roughly 1,300 students. It is named after Swedish diplomat Dag Hammarskjöld...

in Thunder BayThunder Bay-In Canada:Thunder Bay is the name of three places in the province of Ontario, Canada along Lake Superior:*Thunder Bay District, Ontario, a district in Northwestern Ontario*Thunder Bay, a city in Thunder Bay District*Thunder Bay, Unorganized, Ontario...

, OntarioOntarioOntario is a province of Canada, located in east-central Canada. It is Canada's most populous province and second largest in total area. It is home to the nation's most populous city, Toronto, and the nation's capital, Ottawa....

. - Dag Hammarskjöld FoundationDag Hammarskjöld FoundationThe Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation was created in 1962 as Sweden’s national memorial to Dag Hammarskjöld, Secretary General of the United Nations from 1953 until his death in a plane crash on a mission to the Congo...

:In 1962, the Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation was created as Sweden's national memorial to Dag Hammarskjöld.

- Memorial awards:

- Medal: On 22 July 1997, the U.N. Security Council in resolution 1121(1997) established the Dag Hammarskjöld MedalDag Hammarskjöld MedalThe Dag Hammarskjöld Medal is a posthumous award given by the United Nations to military personnel, police, or civilians who lose their lives while serving in a United Nations peacekeeping operation...

in recognition and commemoration of those who have lost their lives as a result of UN peacekeeping operations. - Prize in Peace and Conflict Studies: Colgate UniversityColgate UniversityColgate University is a private liberal arts college in Hamilton, New York, USA. The school was founded in 1819 as a Baptist seminary and later became non-denominational. It is named for the Colgate family who greatly contributed to the university's endowment in the 19th century.Colgate has 52...

annually awards a student the Dag Hammarskjöld Prize in Peace and Conflict Studies based on outstanding work in the program.

- Medal: On 22 July 1997, the U.N. Security Council in resolution 1121(1997) established the Dag Hammarskjöld Medal

- Postage Stamp: United States Postal Service 4-cent value postage stamp, issued on 23 October 1962. Famous for its misprint, this stamp is often referred to as the Dag Hammarskjöld invertDag Hammarskjöld invertThe Dag Hammarskjöld invert is a 4 cent value postage stamp error issued on 23 October 1962 by the United States Postal Service one year after the death of Dag Hammarskjöld, Secretary-General of the United Nations, in an airplane crash...

.

Spirituality and Markings

In 1953, soon after his appointment as United Nations secretary general, Hammarskjöld was interviewed on radio by Edward R. MurrowEdward R. Murrow

Edward Roscoe Murrow, KBE was an American broadcast journalist. He first came to prominence with a series of radio news broadcasts during World War II, which were followed by millions of listeners in the United States and Canada.Fellow journalists Eric Sevareid, Ed Bliss, and Alexander Kendrick...

. In this talk he declared: "But the explanation of how man should live a life of active social service in full harmony with himself as a member of the community of spirit, I found in the writings of those great medieval mystics

Meister Eckhart

Eckhart von Hochheim O.P. , commonly known as Meister Eckhart, was a German theologian, philosopher and mystic, born near Gotha, in the Landgraviate of Thuringia in the Holy Roman Empire. Meister is German for "Master", referring to the academic title Magister in theologia he obtained in Paris...

and Jan van Ruysbroek

His only book, Vägmärken

Vägmärken

Vägmärken is the only book of former UN secretary general, Dag Hammarskjöld, which was published in 1963. It is highly regarded as a classic of contemporary spiritual literature.- Personal significance :...

(Markings), was published in 1963. A collection of his diary reflections, the book starts in 1925, when he was 20 years old, and ends at his death in 1961. This diary was found in his New York house, after his death, along with an undated letter addressed to then Swedish Permanent Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs, Leif Belfrage. In this letter, Dag writes, "These entries provide the only true 'profile' that can be drawn ... If you find them worth publishing, you have my permission to do so". The foreword is written by W.H. Auden, a friend of Dag's. Markings was described by a theologian, the late Henry P. Van Dusen, as "the noblest self-disclosure of spiritual struggle and triumph, perhaps the greatest testament of personal faith written ... in the heat of professional life and amidst the most exacting responsibilities for world peace

World peace

World Peace is an ideal of freedom, peace, and happiness among and within all nations and/or people. World peace is an idea of planetary non-violence by which nations willingly cooperate, either voluntarily or by virtue of a system of governance that prevents warfare. The term is sometimes used to...

and order." Hammarskjöld writes, for example, "We are not permitted to choose the frame of our destiny. But what we put into it is ours. He who wills adventure will experience it — according to the measure of his courage. He who wills sacrifice will be sacrificed — according to the measure of his purity of heart." Markings is characterised by Hammarskjöld's intermingling of prose and haiku

Haiku

' , plural haiku, is a very short form of Japanese poetry typically characterised by three qualities:* The essence of haiku is "cutting"...

poetry in a manner exemplified by the 17th-century Japanese poet Basho

Matsuo Basho

, born , then , was the most famous poet of the Edo period in Japan. During his lifetime, Bashō was recognized for his works in the collaborative haikai no renga form; today, after centuries of commentary, he is recognized as a master of brief and clear haiku...

in his Narrow Roads to the Deep North. In his foreword to Markings, the English poet W. H. Auden

W. H. Auden

Wystan Hugh Auden , who published as W. H. Auden, was an Anglo-American poet,The first definition of "Anglo-American" in the OED is: "Of, belonging to, or involving both England and America." See also the definition "English in origin or birth, American by settlement or citizenship" in See also...

quotes Hammarskjöld as stating "In our age, the road to holiness necessarily passes through the world of action."

The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America commemorates the life of Hammarskjöld as a renewer of society on the anniversary of his death, September 18.

See also

- Dag Hammarskjöld invertDag Hammarskjöld invertThe Dag Hammarskjöld invert is a 4 cent value postage stamp error issued on 23 October 1962 by the United States Postal Service one year after the death of Dag Hammarskjöld, Secretary-General of the United Nations, in an airplane crash...

- The Hammarskjöld Trophy Competition

- http://www.nytimes.com/2011/09/17/opinion/learning-from-hammarskjold.html?_r=1&adxnnl=1&adxnnlx=1316246416-QXhPTtQZzqirCUXwKUdTjg

External links

- Dag Hammarskjöld – biography, quotes, photos and videos

- UNSG Dag Hammarskjold Conference on 9-10 November 2011 at Peace PalacePeace PalaceThe Peace Palace is a building situated in The Hague, Netherlands. It is often called the seat of international law because it houses the International Court of Justice , the Permanent Court of Arbitration, the Hague Academy of International Law, and the extensive Peace Palace Library.In addition...

- Weekly blog exploring Hammarskjöld's political wisdom

- Video of Hammarskjöld's funeral in Pathe archive

- UNSG Ban Ki-Moon Lays Wreath Honouring Dag Hammarskjold of 1 October 2009 and UNSG with King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden

- UNSG Kofi Annan, Dag Hammarskjöld and the 21st century, The Fourth Dag Hammarskjöld Lecture 6 September 2001, Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation and Uppsala University (pdf)

- About Dag Hammarskjöld (Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation)

- United Nations Secretaries-General

- Dag Hammarskjöld, Secretary-General at the official website of the UN

- Biography

- The Nobel Prize

- Letters say Hammarskjöld's death Western plot

- Media briefing by Archbishop Desmond Tutu

- 18 September 1961 UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld is killed and BBC

- Audio of Dag Hammarskjold's response to Russian pressure From UPI Audio Archives

- List of people who converted to Catholicism