Julius Fucík

Encyclopedia

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia or Czecho-Slovakia was a sovereign state in Central Europe which existed from October 1918, when it declared its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992...

journalist, an active member of Communist Party of Czechoslovakia

Communist Party of Czechoslovakia

The Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, in Czech and in Slovak: Komunistická strana Československa was a Communist and Marxist-Leninist political party in Czechoslovakia that existed between 1921 and 1992....

(Komunistická strana Československa, KSČ), and part of the forefront of the anti-Nazi resistance. He was imprisoned, tortured, and executed by the Nazis

Nazism

Nazism, the common short form name of National Socialism was the ideology and practice of the Nazi Party and of Nazi Germany...

.

Early life

Julius Fučík was born into a working-class family in PraguePrague

Prague is the capital and largest city of the Czech Republic. Situated in the north-west of the country on the Vltava river, the city is home to about 1.3 million people, while its metropolitan area is estimated to have a population of over 2.3 million...

. His father was a steelworker. In 1913, Fučík moved with his family from Prague to Plzeň (Pilsen) where he attended the state vocational high school. Already as a twelve-year-old boy he was planning to establish a newspaper named "Slovan" ("The Slav"). He showed himself to be interested in both politics and literature. As a teenager he frequently acted in local amateur theater.

Journalism and politics

In 1920 he took up study in Prague and joined the Czechoslovak Social Democratic Workers' PartyCzech Social Democratic Party

The Czech Social Democratic Party is a social-democratic political party in the Czech Republic.-History:The Social Democratic Czechoslavonic party in Austria was founded on 7 April 1878 in Austria-Hungary representing the Kingdom of Bohemia in the Austrian parliament...

, through which he was later to find himself swept up in the left-wing current. In May 1921 this wing founded the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (CPC). Fučík then first wrote cultural contributions for the local Plzeň CPC newspaper.

After completing his studies, Fučík found a position as an editor with the literary newspaper "Kmen". Within the CPC he became responsible for cultural work. In the year 1929 he went to literary critic František Xaver Šalda's magazine "Tvorba". Moreover, he constantly worked on the CPC newspaper "Rudé Právo

Rudé právo

Rudé právo was the official newspaper of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia....

" and several other journals. In this time Fučík was arrested repeatedly by the Czechoslovakian Secret Police, managing to avoid an eight-month prison sentence in 1934.

In 1930, he visited the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

for four months, including the Czechoslovak collectivist colony Interhelpo

Interhelpo

The Interhelpo was an industrial cooperative of workers and farmers between 1923 and 1943, established for the special purpose of helping to build up socialism in Soviet Kyrgyzstan....

in Central Asia, and painted a very positive picture of the situation there in the book V zemi, kde zítra již znamená včera (In a Land, Where Tomorrow is Already Yesterday, published in 1932). In July 1934, just after Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler was an Austrian-born German politician and the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party , commonly referred to as the Nazi Party). He was Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and head of state from 1934 to 1945...

had suppressed the SA

Sturmabteilung

The Sturmabteilung functioned as a paramilitary organization of the National Socialist German Workers' Party . It played a key role in Adolf Hitler's rise to power in the 1920s and 1930s...

, he visited Bavaria and described his experiences in Cesta do Mníchova (The road to Munich). He went to the Soviet Union again in 1934, this time for two years, and wrote various reports, which again worked to support the Party's strength. After his return, there were heated arguments with authors such as Jiří Weil

Jirí Weil

Jiří Weil was a Czech writer. He was Jewish. His noted works include the two novels Life with a Star , and Mendelssohn Is on the Roof , as well as many short stories, and other novels....

and Jan Slavik, who criticized developments under Joseph Stalin

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

. Fučík took the Stalinist side and criticized such statements critical of Stalin as fatal to the CPC.

In 1938 Fučík married Augusta Kodeřičová, later known as Gusta Fučíková.

In the wake of the Munich Conference, the Prague government disbanded the CPC from September 1938 and the CPC went underground. After Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

's troops invaded Czechoslovakia in March 1939, Fučík moved to his parents' house in Chotiměř (Litoměřice District

Litomerice

Litoměřice is a town at the junction of the rivers Elbe and Ohře in the north part of the Czech Republic, approximately 64 km northwest of Prague....

, Ústecký Kraj

Ústí nad Labem Region

Ústí nad Labem Region is an administrative unit of the Czech Republic, located in the north-western part of its historical region of Bohemia...

) and published in civilian newspapers, especially about historical and literary topics. He also started to work for the now underground CPC. In 1940 the Gestapo started to search for him in Chotiměř because of his cooperation with the CPC, and so he decided to move back to Prague.

Beginning early in 1941, he belonged to the CPC's Central Committee. He provided handbills and tried to publish the Communist Party newspaper Rudé Právo regularly. On 24 April 1942 he and six others were arrested in Prague by the Gestapo

Gestapo

The Gestapo was the official secret police of Nazi Germany. Beginning on 20 April 1934, it was under the administration of the SS leader Heinrich Himmler in his position as Chief of German Police...

, probably rather coincidentally during a police raid. Although Fučík had a gun at the time, he did not use it. The only survivor of the incident, Riva Friedová/Krieglová, claimed in the 1990s that Fučík had had orders to shoot himself to avoid capture.

Notes from the Gallows

Pankrác Prison

Pankrác Prison, officially Prague Pankrác Remand Prison , is a prison in Prague, Czech Republic...

in Prague where he was also interrogated and tortured. In this time arose Fučík's Notes from the Gallows , which was written on pieces of cigarette paper and smuggled out by sympathetic prison warders named Kolínský and Hora. The book describes events in the prison since Fučík's arrest and is filled with hope for a better, Communist future. In later years its authenticity was contested. The book was published in a more "acceptable" version, from which the less pleasant passages, which did not quite fit into everyone's picture of heroic resistance fighters, had been stricken.

Trial and death

In May 1943 Fučík was brought to Germany. He was first detained in BautzenBautzen

Bautzen is a hill-top town in eastern Saxony, Germany, and administrative centre of the eponymous district. It is located on the Spree River. As of 2008, its population is 41,161...

for somewhat more than two months, and afterwards in Berlin. On 25 August 1943 in Berlin, he was accused of high treason

High treason

High treason is criminal disloyalty to one's government. Participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplomats, or its secret services for a hostile and foreign power, or attempting to kill its head of state are perhaps...

in connection with his political activities by the Volksgerichtshof, which was presided over by the notorious Roland Freisler

Roland Freisler

Roland Freisler was a prominent and notorious Nazi lawyer and judge. He was State Secretary of the Reich Ministry of Justice and President of the People's Court , which was set up outside constitutional authority...

. Fučík was found guilty and was sentenced to death along with Jaroslav Klecan, who had been arrested with Fučík. Fučík was hanged two weeks later on 8 September 1943 in Plötzensee Prison

Plötzensee Prison

Plötzensee Prison was a Prussian institution built in Berlin between 1869 and 1879 near the lake Plötzensee, but in the neighbouring borough of Charlottenburg, on Hüttigpfad off Saatwinkler Damm. During Adolf Hitler's time in power from 1933 to 1945, more than 2,500 people were executed at...

in Berlin (not beheaded as is often stated).

After the war, his wife, Gusta Fučíková, who had also been in a Nazi concentration camp, researched and retrieved all of his prison writings. She edited them with help of CPC and published them as Notes from the Gallows in 1947. The book was successful, and its influence increased after the Stalinist takeover of Czechoslovakia in 1948. It has been translated into at least 90 languages.

Fučík as an ideological symbol

The Party found Julius Fučík and his book convenient for use as propaganda and turned them into one of the most visible symbols of the Party. The book was required reading in schools and by the age of 10 every pupil growing up in communist Czechoslovakia was familiar with Fučík's work and life. Fučík became a hero whose portrait was displayed at political meetings. Gusta Fučíková was given a high position in the Party hierarchy (the chairmanship of a women's organization), holding it for decades.Many places were named after Fučík, among them a large entertainment park in Prague (Park kultury a oddechu Julia Fučíka), the city theatre in Jablonec nad Nisou

Jablonec nad Nisou

Jablonec nad Nisou is a town in northern Bohemia, the second largest town of the Liberec Region. It is known as a mountain resort in the Jizera Mountains, an education centre, and a centre of world-production of glass and jewellery...

(1945–98), a factory in Brno

Brno

Brno by population and area is the second largest city in the Czech Republic, the largest Moravian city, and the historical capital city of the Margraviate of Moravia. Brno is the administrative centre of the South Moravian Region where it forms a separate district Brno-City District...

(Elektrotechnické závody Julia Fučíka), a military unit, and countless streets and squares.

In Tom Clancy's 1986 novel Red Storm Rising

Red Storm Rising

Red Storm Rising is a 1986 techno-thriller novel by Tom Clancy and Larry Bond about a Third World War in Europe between NATO and Warsaw Pact forces, set around the mid-1980s...

, about a hypothetical war between the Warsaw Pact and NATO, the Soviet invasion of Iceland is carried out by amphibious troops landed from a freighter named the Julius Fučík.

Reassessment

After the Party lost its power in 1989Velvet Revolution

The Velvet Revolution or Gentle Revolution was a non-violent revolution in Czechoslovakia that took place from November 17 – December 29, 1989...

, the legend of Fučík became a target of scrutiny. It was made public that some parts of the book Notes from the Gallows (around 2%) had been omitted and that the text had been "sanitized" by Gusta Fučíková. There were speculations as to how much information he gave his torturers, and whether he had turned traitor. In 1995 the complete text of the book was published. The part in which Fučík describes how he succumbed to torture was published for the first time. In it, we learn that he gave false information to his captors, saving countless lives among the Czech resistance to the Nazis, which at the time was essentially Communist. This publishing was a logical consequence of political changes, while Fučík's position as untouchable national hero was lost because of its incompatibility with the newly democratized Czech political atmosphere.

Reports

- Reportáže z buržoazní republiky, published in journals, collected in 1948

- V zemi, kde zítra již znamená včera, about the Soviet Union, 1932

- V zemi milované, about the Soviet Union, published posthumously in 1949

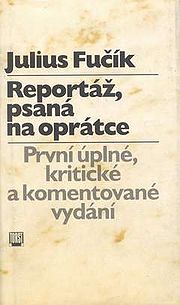

- Reportáž psaná na oprátce (Notes from the Gallows), 1947, complete text in 1995, many editions and translations

Theatrical critiques and literary essays

- Milujeme svoji zem, 1948

- Stati o literatuře, 1951

- Božena Němcová bojující, O Sabinově zradě, Chůva published in Tři studie, 1947.

Quotations

- "It so happens that killing a man is not the greatest evil that one can do that man. The Nazis were specialists, not only in murder and physical torture, but also in man's degradation and debasement, in the extermination of his hope, his attachment to life and his faculty of reasoning."

- "I would like people to know that there were no nameless heroes. That they were human beings who had their names, their faces, their longing, and their hopes, and that for that reason, even the pain of the last one among them was no less than the first one's pain, whose name remains. I would like them all to stay close to you always, like acquaintances, like kin, like you yourselves."

- "Mankind, we loved you — be vigilant."

External links

- Howard FastHoward FastHoward Melvin Fast was an American novelist and television writer. Fast also wrote under the pen names E. V. Cunningham and Walter Ericson.-Early life:Fast was born in New York City...

: Review of Notes from the Gallows, 1948 - Biography