Mary C. Seward

Encyclopedia

Mary Holden Coggeshall Seward (July 9, 1839 – circa September 1, 1919), commonly known as Mary C. Seward, was an American poet

, composer

, and prominent parliamentarian

serving humanitarian and woman's club

movements of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. A number of her works were published under the pseudonym

"Agnes Burney"

, including several developed in collaboration with her spouse, Theodore F. Seward

, an internationally known composer and music educator in his day. She became a groundbreaking advocate for the care and education of blind

babies and young children during her later years, serving as president of the department for the blind of the International Sunshine Society.

. Her father, William Holden Coggeshall, was a veteran of the War of 1812

and a descendent of John Coggeshall

, first president of the colony of Rhode Island

. She was educated at the New London Female Academy where she studied under Hiram W. Farnsworth. In 1860 she married Theodore F. Seward, a composer and music teacher who had previously worked as organist

of a New London church. They lived in Rochester

and Brooklyn in New York

before relocating to East Orange, New Jersey

in 1868.

Though not prolific, her poems and tunes appeared in numerous periodicals and music books. They were published under her name, her pseudonym Agnes Burney, or anonymously on occasion. Her carol

Though not prolific, her poems and tunes appeared in numerous periodicals and music books. They were published under her name, her pseudonym Agnes Burney, or anonymously on occasion. Her carol

The Christmas Bells (circa 1869) has been set to music by at least five different composers. She produced tunes for her own lyrics as well as those of other poets; one of the most widely published was her setting of Mary A. Lathbury's Easter Carol (circa 1883).

She had a long creative relationship with her composer husband and wrote verses for many of his songs. The 1867 collection The Temple Choir, one of Theodore F. Seward's most successful hymnbooks, contained both words and music credited to her pseudonym. She frequently accompanied him on business trips, including the second Europe

an tour of the Fisk Jubilee Singers

in 1875 for which he was voice trainer and musical director.

Seward was involved with the woman’s club

Seward was involved with the woman’s club

movement for forty-seven years. She was a member of Sorosis

, the first American club dedicated to the improvement and advancement of professional women, and an organizer of the National Society of New England Women which she served twice as president. She belonged to the Woman's Club of Orange

since its inception where, as president, she made the motion calling for the formation of the New Jersey State Federation of Women's Clubs. She was a charter member of the International Sunshine Society founded by Cynthia W. Alden

and served it many years as first vice president.

She identified herself as a “parliamentarian

”, one proficient with “the minute details of presiding, of debating, of making motions, of conducting meetings.” Fellow “club women” described her as follows:

The International Sunshine Society, of which Seward was an officer, supported "Sunshine Homes" for the care and education of young children with a variety of disabilities. A Branch for the Blind

The International Sunshine Society, of which Seward was an officer, supported "Sunshine Homes" for the care and education of young children with a variety of disabilities. A Branch for the Blind

was created in 1904 to provide services for blind children below the age of eight that existing public programs either ignored or had been housing with the mentally challenged. The society opposed the then broadly held misconception that blind babies were "feeble-minded". A preliminary Sunshine Home for blind babies was established in a three-room New York City flat and other donated space. Founder Cynthia W. Alden

described the approach:

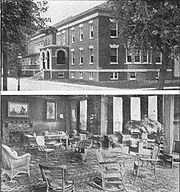

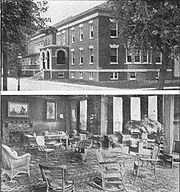

In 1905, the International Sunshine Department (originally Branch) for the Blind was separately incorporated with Seward serving as president. It acquired property in Dyker Heights, Brooklyn, New York for a larger facility to function as a combined home

, nursery

, hospital

, and kindergarten

. They petitioned the New York City Board of Education for support and in 1907 the Dyker Heights Home for Blind Babies became the site of the first public kindergarten for blind children in the United States operated by a major board of education

. Seward subsequently became president of the Arthur Home for Blind Babies in Summit, New Jersey

when it was established as a second combined facility in 1909.

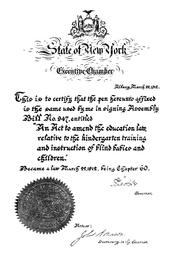

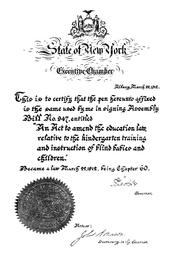

The Department for the Blind also pursued critical legislative support. New York City passed the first legislation addressing the education and training of blind babies and young children in 1908. Thirteen states implemented relevant laws during the decade that followed, including New Jersey in 1911 and New York in 1912. Seward reported that "legislation in behalf of the blind baby was conceded by all members to be the greatest work of the society."

Seward continued to work as an advocate for blind babies and director of Arthur Home for the remainder of her life. As an officer of the International Sunshine Society, she performed these tasks without pay or other compensation. She died suddenly on board a train bound for Buffalo, New York

a few days before September 3, 1919.

Poet

A poet is a person who writes poetry. A poet's work can be literal, meaning that his work is derived from a specific event, or metaphorical, meaning that his work can take on many meanings and forms. Poets have existed since antiquity, in nearly all languages, and have produced works that vary...

, composer

Composer

A composer is a person who creates music, either by musical notation or oral tradition, for interpretation and performance, or through direct manipulation of sonic material through electronic media...

, and prominent parliamentarian

Parliamentarian (consultant)

A parliamentarian is an expert on parliamentary procedure who advises organizations and deliberative assemblies. This sense of the term "parliamentarian" is distinct from the usage of the same term to mean a member of Parliament....

serving humanitarian and woman's club

Women's club

Women’s clubs, also known as woman's clubs, first arose in the United States during the post-Civil War period, in both the North and the South. As a result of increased leisure time due to modern household advances, middle-class women had more time to engage in intellectual pursuits...

movements of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. A number of her works were published under the pseudonym

Pseudonym

A pseudonym is a name that a person assumes for a particular purpose and that differs from his or her original orthonym...

"Agnes Burney"

, including several developed in collaboration with her spouse, Theodore F. Seward

Theodore Frelinghuysen Seward

Theodore Frelinghuysen Seward the Founder of the Brotherhood of Christian Unity and the Don't Worry Club.-Biography:He was born in Florida, New York, January 25, 1835...

, an internationally known composer and music educator in his day. She became a groundbreaking advocate for the care and education of blind

Blindness

Blindness is the condition of lacking visual perception due to physiological or neurological factors.Various scales have been developed to describe the extent of vision loss and define blindness...

babies and young children during her later years, serving as president of the department for the blind of the International Sunshine Society.

Early years

Seward was born Mary Holden Coggeshall in New London, ConnecticutNew London, Connecticut

New London is a seaport city and a port of entry on the northeast coast of the United States.It is located at the mouth of the Thames River in New London County, southeastern Connecticut....

. Her father, William Holden Coggeshall, was a veteran of the War of 1812

War of 1812

The War of 1812 was a military conflict fought between the forces of the United States of America and those of the British Empire. The Americans declared war in 1812 for several reasons, including trade restrictions because of Britain's ongoing war with France, impressment of American merchant...

and a descendent of John Coggeshall

John Coggeshall

John Coggeshall was one of the founders of Rhode Island and the first President of all four towns in the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. Coming from Essex, England as a successful merchant in the silk trade, Coggeshall arrived in the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1632 and quickly...

, first president of the colony of Rhode Island

Rhode Island

The state of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, more commonly referred to as Rhode Island , is a state in the New England region of the United States. It is the smallest U.S. state by area...

. She was educated at the New London Female Academy where she studied under Hiram W. Farnsworth. In 1860 she married Theodore F. Seward, a composer and music teacher who had previously worked as organist

Organist

An organist is a musician who plays any type of organ. An organist may play solo organ works, play with an ensemble or orchestra, or accompany one or more singers or instrumental soloists...

of a New London church. They lived in Rochester

Rochester, New York

Rochester is a city in Monroe County, New York, south of Lake Ontario in the United States. Known as The World's Image Centre, it was also once known as The Flour City, and more recently as The Flower City...

and Brooklyn in New York

New York

New York is a state in the Northeastern region of the United States. It is the nation's third most populous state. New York is bordered by New Jersey and Pennsylvania to the south, and by Connecticut, Massachusetts and Vermont to the east...

before relocating to East Orange, New Jersey

East Orange, New Jersey

East Orange is a city in Essex County, New Jersey, United States. As of the 2010 United States Census the city's population 64,270, making it the state's 20th largest municipality, having dropped 5,554 residents from its population of 69,824 in the 2000 Census, when it was the state's 14th most...

in 1868.

Poet and composer

Christmas carol

A Christmas carol is a carol whose lyrics are on the theme of Christmas or the winter season in general and which are traditionally sung in the period before Christmas.-History:...

The Christmas Bells (circa 1869) has been set to music by at least five different composers. She produced tunes for her own lyrics as well as those of other poets; one of the most widely published was her setting of Mary A. Lathbury's Easter Carol (circa 1883).

She had a long creative relationship with her composer husband and wrote verses for many of his songs. The 1867 collection The Temple Choir, one of Theodore F. Seward's most successful hymnbooks, contained both words and music credited to her pseudonym. She frequently accompanied him on business trips, including the second Europe

Europe

Europe is, by convention, one of the world's seven continents. Comprising the westernmost peninsula of Eurasia, Europe is generally 'divided' from Asia to its east by the watershed divides of the Ural and Caucasus Mountains, the Ural River, the Caspian and Black Seas, and the waterways connecting...

an tour of the Fisk Jubilee Singers

Fisk Jubilee Singers

The Fisk Jubilee Singers are an African-American a cappella ensemble, consisting of students at Fisk University. The first group was organized in 1871 to tour and raise funds for their college. Their early repertoire consisted mostly of traditional spirituals, but included some Stephen Foster songs...

in 1875 for which he was voice trainer and musical director.

Club woman and parliamentarian

Women's club

Women’s clubs, also known as woman's clubs, first arose in the United States during the post-Civil War period, in both the North and the South. As a result of increased leisure time due to modern household advances, middle-class women had more time to engage in intellectual pursuits...

movement for forty-seven years. She was a member of Sorosis

Sorosis

Sorosis was the first professional women's club in the United States. The club was organized in New York City with 12 members in March 1868, by Jane Cunningham Croly...

, the first American club dedicated to the improvement and advancement of professional women, and an organizer of the National Society of New England Women which she served twice as president. She belonged to the Woman's Club of Orange

Orange, New Jersey

The City of Orange is a city and township in Essex County, New Jersey, United States. As of the 2010 United States Census, the township population was 30,134...

since its inception where, as president, she made the motion calling for the formation of the New Jersey State Federation of Women's Clubs. She was a charter member of the International Sunshine Society founded by Cynthia W. Alden

Cynthia May Alden

Cynthia May Westover Alden , commonly known as Cynthia W. Alden, was an American journalist, author and New York municipal employee.-Biography:She was born in Afton, Iowa...

and served it many years as first vice president.

She identified herself as a “parliamentarian

Parliamentarian (consultant)

A parliamentarian is an expert on parliamentary procedure who advises organizations and deliberative assemblies. This sense of the term "parliamentarian" is distinct from the usage of the same term to mean a member of Parliament....

”, one proficient with “the minute details of presiding, of debating, of making motions, of conducting meetings.” Fellow “club women” described her as follows:

Philanthrophy and later years

Blindness

Blindness is the condition of lacking visual perception due to physiological or neurological factors.Various scales have been developed to describe the extent of vision loss and define blindness...

was created in 1904 to provide services for blind children below the age of eight that existing public programs either ignored or had been housing with the mentally challenged. The society opposed the then broadly held misconception that blind babies were "feeble-minded". A preliminary Sunshine Home for blind babies was established in a three-room New York City flat and other donated space. Founder Cynthia W. Alden

Cynthia May Alden

Cynthia May Westover Alden , commonly known as Cynthia W. Alden, was an American journalist, author and New York municipal employee.-Biography:She was born in Afton, Iowa...

described the approach:

In 1905, the International Sunshine Department (originally Branch) for the Blind was separately incorporated with Seward serving as president. It acquired property in Dyker Heights, Brooklyn, New York for a larger facility to function as a combined home

Home

A home is a place of residence or refuge. When it refers to a building, it is usually a place in which an individual or a family can rest and store personal property. Most modern-day households contain sanitary facilities and a means of preparing food. Animals have their own homes as well, either...

, nursery

Nursery school

A nursery school is a school for children between the ages of one and five years, staffed by suitably qualified and other professionals who encourage and supervise educational play rather than simply providing childcare...

, hospital

Hospital

A hospital is a health care institution providing patient treatment by specialized staff and equipment. Hospitals often, but not always, provide for inpatient care or longer-term patient stays....

, and kindergarten

Kindergarten

A kindergarten is a preschool educational institution for children. The term was created by Friedrich Fröbel for the play and activity institute that he created in 1837 in Bad Blankenburg as a social experience for children for their transition from home to school...

. They petitioned the New York City Board of Education for support and in 1907 the Dyker Heights Home for Blind Babies became the site of the first public kindergarten for blind children in the United States operated by a major board of education

Board of education

A board of education or a school board or school committee is the title of the board of directors or board of trustees of a school, local school district or higher administrative level....

. Seward subsequently became president of the Arthur Home for Blind Babies in Summit, New Jersey

Summit, New Jersey

Summit is a city in Union County, New Jersey, United States. At the 2010 United States Census, the city's population was 21,457. Summit had the 16th-highest per capita income in the state as of the 2000 Census....

when it was established as a second combined facility in 1909.

The Department for the Blind also pursued critical legislative support. New York City passed the first legislation addressing the education and training of blind babies and young children in 1908. Thirteen states implemented relevant laws during the decade that followed, including New Jersey in 1911 and New York in 1912. Seward reported that "legislation in behalf of the blind baby was conceded by all members to be the greatest work of the society."

Seward continued to work as an advocate for blind babies and director of Arthur Home for the remainder of her life. As an officer of the International Sunshine Society, she performed these tasks without pay or other compensation. She died suddenly on board a train bound for Buffalo, New York

Buffalo, New York

Buffalo is the second most populous city in the state of New York, after New York City. Located in Western New York on the eastern shores of Lake Erie and at the head of the Niagara River across from Fort Erie, Ontario, Buffalo is the seat of Erie County and the principal city of the...

a few days before September 3, 1919.