Polish United Workers' Party

Encyclopedia

The Polish United Workers' Party (PUWP, - PZPR) was the Communist party which governed the People's Republic of Poland

from 1948 to 1989. Ideologically it was based on the theories of Marxism-Leninism

.

Its main goal was to create a Communist society and help to propagate Communism all over the world. On paper, the party was organised on the basis of democratic centralism

, which assumed a democratic appointment of authorities, making decisions, and managing its activity. Yet in fact, the key roles were played by the Central Committee

, its Politburo

and Secretariat, which were subject to the strict control of the authorities of the Soviet Union

. These authorities decided about the policy and composition of the main organs; although, according to the statute, it was a responsibility of the members of the congress, which was held every five or six years. Between sessions, party conferences of the regional, county, district and work committees were taking place. The smallest organizational unit of the PUWP was the Fundamental Party Organization (FPO), which functioned in work places, schools, cultural institutions, etc.

The main part in the PUWP was played by professional politicians, or the so-called "party's hard core", formed by people who were recommended to manage the main state institutions, social organizations, and trade unions. In the crowning time of the PUWP's development (the end of ‘70s) it consisted of over 3.5 million members. The Political Office of the Central Committee, Secretariat and regional committees appointed the key posts not only within the party, but also in all organizations having ‘state’ in its name – from central offices to even small state and cooperative companies. It was called the nomenklatura

system of the state and economy management. In certain areas of the economy, e.g. in agriculture, the nomenklatura system was controlled with an approval of the PUWP and by its allied parties, the United People's Party

(agriculture and food production), and the Democratic Party

(trade community, small enterprise, some cooperatives). After martial law

, the Patriotic Movement for National Rebirth

was founded to organize these and other parties.

(PPR) and Polish Socialist Party

(PPS) during meetings held from 15 to 21 December 1948. The unification was possible because the PPS activists who opposed unification (or rather absorption by Communists) had been forced out of the party. Similarly, the members of the PPR who were accused of "rightist – nationalistic deviation" were expelled. "Rightist-nationalist deviation" (Polish

: odchylenie prawicowo-nacjonalistyczne) was a political

propaganda

term used by the Polish stalinists against prominent activists, such as Władysław Gomułka and Marian Spychalski

who opposed Soviet involvement in the Polish interior affairs, as well as internationalism

displayed by the creation of the Cominform

and the subsequent merger that created the PZPR. It is believed that it was Joseph Stalin

who put pressure on Bolesław Bierut and Jakub Berman

to remove Gomułka and Spychalski as well as their followers from power in 1948. It is estimated that over 25% of socialists were removed from power or expelled from political life.

Bolesław Bierut, an NKVD

agent, and a hard Stalinist

served as first Secretary General of the ruling Polish United Workers Party from 1948 to 1956, playing a leading role in the Sovietisation of Poland and the installation of her most repressive regime. From 1947 to 1952, he served as President and then (after the abolition of the Presidency) as Prime Minister.

Bierut oversaw the trials of many Polish wartime military leaders, such as General Stanisław Tatar and Brig. General Emil August Fieldorf

, as well as 40 members of the Wolność i Niezawisłość (Freedom and Independence) organisation, various Church officials and many other opponents of the new regime including the "hero of Auschwitz", Witold Pilecki

, condemned to death during secret trial

s. Bierut signed many of those death sentences.

Bierut's death in Moscow

in 1956 (shortly after attending the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union) gave rise to much speculation about poison

ing or a suicide

, and symbolically marked the end of the era of Stalinism

in Poland.

In 1956, shortly after the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, the PUWP leadership split in two factions, dubbed Natolinians and Puławians. The Natolin faction - named after the place where its meetings took place, in a government villa in Natolin

In 1956, shortly after the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, the PUWP leadership split in two factions, dubbed Natolinians and Puławians. The Natolin faction - named after the place where its meetings took place, in a government villa in Natolin

- were against the post-Stalinist liberalization programs (Gomułka thaw) and they proclaimed simple nationalist and antisemitic slogans as part of a strategy to gain power. The most well known members included Franciszek Jóźwiak, Wiktor Kłosiewicz, Zenon Nowak

, Aleksander Zawadzki

, Władysław Dworakowski, Hilary Chełchowski.

The Puławian faction - the name comes from the Puławska Street in Warsaw, on which many of the members lived - sought great liberalization of socialism in Poland. After the events of Poznań June, they successfully backed the candidature of Władysław Gomułka for First Secretary of PZPR, thus imposing a major setback upon Natolinians. Among the most prominent members were Roman Zambrowski

and Leon Kasman. Both factions disappeared towards the end of the 1950s.

Initially very popular for his reforms and seeking a "Polish way to socialism", and beginning an era known as Gomułka's thaw, he came under Soviet pressure. In the 1960s he supported persecution of the Roman Catholic Church

and intellectuals (notably Leszek Kołakowski who was forced into exile). He participated in the Warsaw Pact

intervention in Czechoslovakia

in 1968. At that time he was also responsible for persecuting students as well as toughening censorship

of the media. In 1968 he incited an anti-Zionist propaganda campaign, as a result of Soviet bloc opposition to the Six-Day War

.

This was a thinly veiled anti-semitic campaign designed to keep himself in power by shifting the attention of the populace from stagnating economy and Communist mismanagement. Gomułka later claimed that this was not deliberate.

In December 1970, a bloody clash with shipyard

workers in which several dozen workers were fatally shot forced his resignation (officially for health reasons; he had in fact suffered a stroke

). A dynamic younger man, Edward Gierek

, took over the Party leadership and tensions eased.

In late 1960s, Edward Gierek

In late 1960s, Edward Gierek

had created a personal power base and become the recognized leader of the young technocrat faction of the party. When rioting over economic conditions broke out in late 1970, Gierek replaced Władysław Gomułka as party first secretary. Gierek promised economic reform and instituted a program to modernize industry and increase the availability of consumer goods, doing so mostly through foreign loans. His good relations with Western politicians, especially France's Valéry Giscard d'Estaing

and West Germany's Helmut Schmidt

, were a catalyst for his receiving western aid and loans.

The standard of living increased markedly in the Poland of the 1970s, and for a time he was hailed a miracle-worker. The economy, however, began to falter during the 1973 oil crisis

, and by 1976 price increases became necessary. New riots broke out in June 1976

, and although they were forcibly suppressed, the planned price increases were canceled. High foreign debts, food shortages, and an outmoded industrial base compelled a new round of economic reforms in 1980. Once again, price increases set off protests across the country, especially in the Gdańsk and Szczecin shipyards. Gierek was forced to grant legal status to Solidarity and to concede the right to strike. (Gdańsk Agreement

).

Shortly thereafter, in early September 1980, Gierek was replaced as by Stanisław Kania as General Secretary of the party by the Central Committee, amidst much social and economic unrest.

Kania admitted that the party had made many economic mistakes, and advocated working with Catholic and trade unionist opposition groups. He met with Solidarity Union

leader Lech Wałęsa

, and other critics of the party. Though Kania agreed with his predecessors that the Communist Party must maintain control of Poland, he never assured the Soviets that Poland would not pursue actions independent of the Soviet Union. On October 18, 1981, the Central Committee of the Party withdrew confidence on him, and Kania was replaced by Prime Minister (and Minister of Defence) Gen. Wojciech Jaruzelski

.

On 11 February 1981, Jaruzelski was elected Prime Minister of Poland

On 11 February 1981, Jaruzelski was elected Prime Minister of Poland

and became the First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Polish United Workers Party on October 18 the same year.

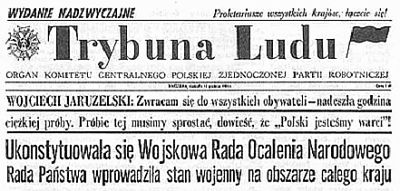

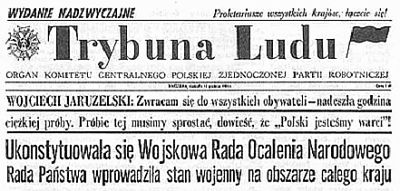

Before initiating the plan, he presented it to Soviet Premier Nikolai Tikhonov

. On 13 December 1981, Jaruzelski imposed martial law in Poland

In 1982 Jaruzelski revitalized the Front of National Unity

, the organization the Communists used to manage their satellite parties, as the Patriotic Movement for National Rebirth

.

In 1985, Jaruzelski resigned as prime minister and defence minister and became chairman of the Polish Council of State

, a post equivalent to that of president or a dictator

, with his power centered on and firmly entrenched in his coterie of "LWP" generals and lower ranks officers of the Polish Communist Army.

The policies of Mikhail Gorbachev

also stimulated political reform

in Poland. By the close of the tenth plenary session in December 1988, the Communist Party was forced, after strikes

, to approach leaders of Solidarity for talks.

From 6 February to 15 April 1989, negotiations were held between 13 working group

s during 94 sessions of the roundtable talks

.

These negotiations resulted in an agreement which stated that a great degree of political power would be given to a newly created bicameral legislature. It also created a new post of president

to act as head of state and chief executive. Solidarity was also declared a legal organization. During the following Polish elections the Communists won 65 percent of the seats in the Sejm

, though the seats won were guaranteed and the Communists were unable to gain a majority, while 99 out of the 100 seats in the Senate freely contested were won by Solidarity-backed candidates. Jaruzelski won the presidential ballot by one vote.

Jaruzelski was unsuccessful in convincing Wałęsa

to include Solidarity in a "grand coalition" with the Communists, and resigned his position of general secretary of the Polish Communist Party. The Communists' two allied parties broke their long-standing alliance, forcing Jaruzelski to appoint Solidarity's Tadeusz Mazowiecki

as the country's first non-Communist prime minister since 1948. Jaruzelski resigned as Poland's President in 1990, being succeeded by Wałęsa in December.

Starting from January 1990, the collapse of the PUWP became inevitable. In the whole country, public occupation of the party building started in order to prevent stealing the party's possessions and destroying or taking the archives. On 29 January 1990, XI Congress was held, which was supposed to recreate the party. Finally, the PUWP dissolved, and some of its members decided to establish two new social-democratic parties. They get over $1 million from the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

Starting from January 1990, the collapse of the PUWP became inevitable. In the whole country, public occupation of the party building started in order to prevent stealing the party's possessions and destroying or taking the archives. On 29 January 1990, XI Congress was held, which was supposed to recreate the party. Finally, the PUWP dissolved, and some of its members decided to establish two new social-democratic parties. They get over $1 million from the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

known as the Moscow loan.

The former activists of the PUWP established the Social Democracy of the Republic of Poland

(in Polish: Socjaldemokracja Rzeczpospolitej Polskiej, SdRP), of which the main organizers were Leszek Miller

and Mieczysław Rakowski. The SdRP was supposed (among other things) to take over all rights and duties of the PUWP, and help to divide out the property of the former PUWP. Up to the end of ‘80s, it had considerable incomes mainly from managed properties and from the RSW company ‘Press- Book-Traffic’, which in turn had special tax concessions. During this period, the incomes from membership fees constituted only 30% of the PUWP's revenues. After the dissolution of the PUWP and the establishment of the SdRP, the rest of the activists formed the Social Democratic Union of the Republic of Poland (USdRP), which changed its name to the Polish Social Democratic Union, and The 8th July Movement.

At the end of 1990, there was an intense debate in the Sejm on the takeover of the wealth that belonged to the former PUWP. Over 3000 buildings and premises were included in the wealth and almost half of it was used without legal basis. Supporters of the acquisition argued that the wealth was built on the basis of plunder and the Treasury grant collected by the whole society. Opponents of SdRP (Social Democratic Party of the Republic of Poland) claimed that the wealth was created from membership fees; therefore, they demanded wealth inheritance for SdPR which at that time administered the wealth. Personal property and the accounts of the former PUWP were not subject to control of a parliamentary committee.

On 9 November 1990, the Sejm passed "The resolution about the acquisition of the wealth that belonged to the former PUWP". This resolution was supposed to result in a final takeover of the PUWP real estate by the Treasury. As a result, only a part of the real estate was taken over mainly for a local government by 1992, whereas a legal dispute over the other party carried on till 2000. Personal property and finances of the former PUWP practically disappeared. According to the declaration of SdRP MP's, 90-95% of the party's wealth was allocated for gratuity or was donated for a social assistance.

Consequently, in second circulation a banknote with a printed inscription appeared: The last P.Z.P.R Congress closed the proceedings – "Workers of the World, forgive me". Near the inscriptions there is also an image of Lenin praying with rosary.

had also its seat in this building.

People's Republic of Poland

The People's Republic of Poland was the official name of Poland from 1952 to 1990. Although the Soviet Union took control of the country immediately after the liberation from Nazi Germany in 1944, the name of the state was not changed until eight years later...

from 1948 to 1989. Ideologically it was based on the theories of Marxism-Leninism

Marxism-Leninism

Marxism–Leninism is a communist ideology, officially based upon the theories of Marxism and Vladimir Lenin, that promotes the development and creation of a international communist society through the leadership of a vanguard party over a revolutionary socialist state that represents a dictatorship...

.

The Party's Program and Goals

Up until 1989 the PUWP held dictatorial powers (the amendment to the constitution of 1976 mentioned "a leading national force"), and controlled an unwieldy bureaucracy, the military, the secret police, and the economy.Its main goal was to create a Communist society and help to propagate Communism all over the world. On paper, the party was organised on the basis of democratic centralism

Democratic centralism

Democratic centralism is the name given to the principles of internal organization used by Leninist political parties, and the term is sometimes used as a synonym for any Leninist policy inside a political party...

, which assumed a democratic appointment of authorities, making decisions, and managing its activity. Yet in fact, the key roles were played by the Central Committee

Central Committee of the Polish United Workers Party

Central Committee of the Polish United Workers' Party was the central ruling body of the Polish United Workers' Party, the dominant political party in the People's Republic of Poland .-Functions:...

, its Politburo

Politburo of the Polish United Workers' Party

The Politburo of the Polish United Workers Party was the chief executive body of the ruling Polish Communist apparatus between 1948–1989. Nearly all key figures of the regime had membership in the Politburo. The Politburo of the PUWP typically had between 9-15 full members at any one time...

and Secretariat, which were subject to the strict control of the authorities of the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

. These authorities decided about the policy and composition of the main organs; although, according to the statute, it was a responsibility of the members of the congress, which was held every five or six years. Between sessions, party conferences of the regional, county, district and work committees were taking place. The smallest organizational unit of the PUWP was the Fundamental Party Organization (FPO), which functioned in work places, schools, cultural institutions, etc.

The main part in the PUWP was played by professional politicians, or the so-called "party's hard core", formed by people who were recommended to manage the main state institutions, social organizations, and trade unions. In the crowning time of the PUWP's development (the end of ‘70s) it consisted of over 3.5 million members. The Political Office of the Central Committee, Secretariat and regional committees appointed the key posts not only within the party, but also in all organizations having ‘state’ in its name – from central offices to even small state and cooperative companies. It was called the nomenklatura

Nomenklatura

The nomenklatura were a category of people within the Soviet Union and other Eastern Bloc countries who held various key administrative positions in all spheres of those countries' activity: government, industry, agriculture, education, etc., whose positions were granted only with approval by the...

system of the state and economy management. In certain areas of the economy, e.g. in agriculture, the nomenklatura system was controlled with an approval of the PUWP and by its allied parties, the United People's Party

United People's Party (Poland)

The United People's Party was an agrarian political party in the People's Republic of Poland. It was formed on 27 November 1949 from the merger of the communist Stronnictwo Ludowe party with remnants of the independent People's Party of Stanisław Mikołajczyk .ZSL became - as intended from its very...

(agriculture and food production), and the Democratic Party

Democratic Party (Poland)

The Democratic Party is a Polish centrist party. The party faced a revival in 2009, when it was joined by liberal politician Paweł Piskorski, formerly member of Civic Platform.-History:The party was established on April 15, 1939...

(trade community, small enterprise, some cooperatives). After martial law

Martial law in Poland

Martial law in Poland refers to the period of time from December 13, 1981 to July 22, 1983, when the authoritarian government of the People's Republic of Poland drastically restricted normal life by introducing martial law in an attempt to crush political opposition to it. Thousands of opposition...

, the Patriotic Movement for National Rebirth

Patriotic Movement for National Rebirth

Patriotyczny Ruch Odrodzenia Narodowego was a Polish communist organization. It was created in the aftermath of the martial law in Poland...

was founded to organize these and other parties.

Establishing and Sovietisation period

The Polish United Worker's Party was established at the unification congress of the Polish Workers' PartyPolish Workers' Party

The Polish Workers' Party was a communist party in Poland from 1942 to 1948. It was founded as a reconstitution of the Communist Party of Poland, and merged with the Polish Socialist Party in 1948 to form the Polish United Workers' Party.-History:...

(PPR) and Polish Socialist Party

Polish Socialist Party

The Polish Socialist Party was one of the most important Polish left-wing political parties from its inception in 1892 until 1948...

(PPS) during meetings held from 15 to 21 December 1948. The unification was possible because the PPS activists who opposed unification (or rather absorption by Communists) had been forced out of the party. Similarly, the members of the PPR who were accused of "rightist – nationalistic deviation" were expelled. "Rightist-nationalist deviation" (Polish

Polish language

Polish is a language of the Lechitic subgroup of West Slavic languages, used throughout Poland and by Polish minorities in other countries...

: odchylenie prawicowo-nacjonalistyczne) was a political

Politics

Politics is a process by which groups of people make collective decisions. The term is generally applied to the art or science of running governmental or state affairs, including behavior within civil governments, but also applies to institutions, fields, and special interest groups such as the...

propaganda

Propaganda

Propaganda is a form of communication that is aimed at influencing the attitude of a community toward some cause or position so as to benefit oneself or one's group....

term used by the Polish stalinists against prominent activists, such as Władysław Gomułka and Marian Spychalski

Marian Spychalski

Marian "Marek" Spychalski was a Polish architect, military commander, and communist politician.Born to a working-class family in Łódź, he graduated from the Faculty of Architecture at the Warsaw University of Technology in 1931...

who opposed Soviet involvement in the Polish interior affairs, as well as internationalism

Internationalism (politics)

Internationalism is a political movement which advocates a greater economic and political cooperation among nations for the theoretical benefit of all...

displayed by the creation of the Cominform

Cominform

Founded in 1947, Cominform is the common name for what was officially referred to as the Information Bureau of the Communist and Workers' Parties...

and the subsequent merger that created the PZPR. It is believed that it was Joseph Stalin

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

who put pressure on Bolesław Bierut and Jakub Berman

Jakub Berman

Jakub Berman was born into a middle-class Jewish family. Berman first became a prominent communist in prewar Poland. Toward the end of World War II he joined the Politburo of the Soviet-formed Polish United Workers' Party...

to remove Gomułka and Spychalski as well as their followers from power in 1948. It is estimated that over 25% of socialists were removed from power or expelled from political life.

Bolesław Bierut, an NKVD

NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs was the public and secret police organization of the Soviet Union that directly executed the rule of power of the Soviets, including political repression, during the era of Joseph Stalin....

agent, and a hard Stalinist

Stalinism

Stalinism refers to the ideology that Joseph Stalin conceived and implemented in the Soviet Union, and is generally considered a branch of Marxist–Leninist ideology but considered by some historians to be a significant deviation from this philosophy...

served as first Secretary General of the ruling Polish United Workers Party from 1948 to 1956, playing a leading role in the Sovietisation of Poland and the installation of her most repressive regime. From 1947 to 1952, he served as President and then (after the abolition of the Presidency) as Prime Minister.

Bierut oversaw the trials of many Polish wartime military leaders, such as General Stanisław Tatar and Brig. General Emil August Fieldorf

Emil August Fieldorf

Emil August Fieldorf was a Polish Brigadier General. He was Deputy Commander-in-Chief of the Home Army or AK, after the failure of the Warsaw Uprising...

, as well as 40 members of the Wolność i Niezawisłość (Freedom and Independence) organisation, various Church officials and many other opponents of the new regime including the "hero of Auschwitz", Witold Pilecki

Witold Pilecki

Witold Pilecki was a soldier of the Second Polish Republic, the founder of the Secret Polish Army resistance group and a member of the Home Army...

, condemned to death during secret trial

Secret trial

A secret trial is a trial that is not open to the public, nor generally reported in the news, especially any in-trial proceedings. Generally no official record of the case or the judge's verdict is made available. Often there is no indictment...

s. Bierut signed many of those death sentences.

Bierut's death in Moscow

Moscow

Moscow is the capital, the most populous city, and the most populous federal subject of Russia. The city is a major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation centre of Russia and the continent...

in 1956 (shortly after attending the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union) gave rise to much speculation about poison

Poison

In the context of biology, poisons are substances that can cause disturbances to organisms, usually by chemical reaction or other activity on the molecular scale, when a sufficient quantity is absorbed by an organism....

ing or a suicide

Suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Suicide is often committed out of despair or attributed to some underlying mental disorder, such as depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, alcoholism, or drug abuse...

, and symbolically marked the end of the era of Stalinism

Stalinism

Stalinism refers to the ideology that Joseph Stalin conceived and implemented in the Soviet Union, and is generally considered a branch of Marxist–Leninist ideology but considered by some historians to be a significant deviation from this philosophy...

in Poland.

Gomułka's autarchic communism

Natolin

Natolin is a historic park and nature reserve on the southern edge of Warsaw, Poland. "Natolin" is also the name of a neighborhood located to the west of the park — a part of Warsaw's southernmost Ursynów district....

- were against the post-Stalinist liberalization programs (Gomułka thaw) and they proclaimed simple nationalist and antisemitic slogans as part of a strategy to gain power. The most well known members included Franciszek Jóźwiak, Wiktor Kłosiewicz, Zenon Nowak

Zenon Nowak

Zenon Nowak was a Communist activist and politician in the People's Republic of Poland. One of the members of the pro-Soviet Natolin faction of the PZPR Central Committee during the Polish October of 1956.-References:...

, Aleksander Zawadzki

Aleksander Zawadzki

Aleksander Zawadzki was a Polish Communist political figure and head of state of Poland from 1952 to 1964.A member of the Communist Youth Union, Zawadzki went into exile in the Soviet Union in 1931, after spending six years in prison for "subversive activities." He returned to Poland in 1939, just...

, Władysław Dworakowski, Hilary Chełchowski.

The Puławian faction - the name comes from the Puławska Street in Warsaw, on which many of the members lived - sought great liberalization of socialism in Poland. After the events of Poznań June, they successfully backed the candidature of Władysław Gomułka for First Secretary of PZPR, thus imposing a major setback upon Natolinians. Among the most prominent members were Roman Zambrowski

Roman Zambrowski

Roman Zambrowski was a Polish communist activist. He is a father of journalist Antoni Zambrowski....

and Leon Kasman. Both factions disappeared towards the end of the 1950s.

Initially very popular for his reforms and seeking a "Polish way to socialism", and beginning an era known as Gomułka's thaw, he came under Soviet pressure. In the 1960s he supported persecution of the Roman Catholic Church

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the world's largest Christian church, with over a billion members. Led by the Pope, it defines its mission as spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ, administering the sacraments and exercising charity...

and intellectuals (notably Leszek Kołakowski who was forced into exile). He participated in the Warsaw Pact

Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Treaty Organization of Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance , or more commonly referred to as the Warsaw Pact, was a mutual defense treaty subscribed to by eight communist states in Eastern Europe...

intervention in Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia or Czecho-Slovakia was a sovereign state in Central Europe which existed from October 1918, when it declared its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992...

in 1968. At that time he was also responsible for persecuting students as well as toughening censorship

Censorship

thumb|[[Book burning]] following the [[1973 Chilean coup d'état|1973 coup]] that installed the [[Military government of Chile |Pinochet regime]] in Chile...

of the media. In 1968 he incited an anti-Zionist propaganda campaign, as a result of Soviet bloc opposition to the Six-Day War

Six-Day War

The Six-Day War , also known as the June War, 1967 Arab-Israeli War, or Third Arab-Israeli War, was fought between June 5 and 10, 1967, by Israel and the neighboring states of Egypt , Jordan, and Syria...

.

This was a thinly veiled anti-semitic campaign designed to keep himself in power by shifting the attention of the populace from stagnating economy and Communist mismanagement. Gomułka later claimed that this was not deliberate.

In December 1970, a bloody clash with shipyard

Shipyard

Shipyards and dockyards are places which repair and build ships. These can be yachts, military vessels, cruise liners or other cargo or passenger ships. Dockyards are sometimes more associated with maintenance and basing activities than shipyards, which are sometimes associated more with initial...

workers in which several dozen workers were fatally shot forced his resignation (officially for health reasons; he had in fact suffered a stroke

Stroke

A stroke, previously known medically as a cerebrovascular accident , is the rapidly developing loss of brain function due to disturbance in the blood supply to the brain. This can be due to ischemia caused by blockage , or a hemorrhage...

). A dynamic younger man, Edward Gierek

Edward Gierek

Edward Gierek was a Polish communist politician.He was born in Porąbka, outside of Sosnowiec. He lost his father to a mining accident in a pit at the age of four. His mother married again and emigrated to northern France, where he was raised. He joined the French Communist Party in 1931 and was...

, took over the Party leadership and tensions eased.

Gierek's economic opening

Edward Gierek

Edward Gierek was a Polish communist politician.He was born in Porąbka, outside of Sosnowiec. He lost his father to a mining accident in a pit at the age of four. His mother married again and emigrated to northern France, where he was raised. He joined the French Communist Party in 1931 and was...

had created a personal power base and become the recognized leader of the young technocrat faction of the party. When rioting over economic conditions broke out in late 1970, Gierek replaced Władysław Gomułka as party first secretary. Gierek promised economic reform and instituted a program to modernize industry and increase the availability of consumer goods, doing so mostly through foreign loans. His good relations with Western politicians, especially France's Valéry Giscard d'Estaing

Valéry Giscard d'Estaing

Valéry Marie René Georges Giscard d'Estaing is a French centre-right politician who was President of the French Republic from 1974 until 1981...

and West Germany's Helmut Schmidt

Helmut Schmidt

Helmut Heinrich Waldemar Schmidt is a German Social Democratic politician who served as Chancellor of West Germany from 1974 to 1982. Prior to becoming chancellor, he had served as Minister of Defence and Minister of Finance. He had also served briefly as Minister of Economics and as acting...

, were a catalyst for his receiving western aid and loans.

The standard of living increased markedly in the Poland of the 1970s, and for a time he was hailed a miracle-worker. The economy, however, began to falter during the 1973 oil crisis

1973 oil crisis

The 1973 oil crisis started in October 1973, when the members of Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries or the OAPEC proclaimed an oil embargo. This was "in response to the U.S. decision to re-supply the Israeli military" during the Yom Kippur war. It lasted until March 1974. With the...

, and by 1976 price increases became necessary. New riots broke out in June 1976

June 1976 protests

June 1976 is the name of a series of protests and demonstrations in People's Republic of Poland. The protests took place after Prime Minister Piotr Jaroszewicz revealed the plan for a sudden increase in the price of many basic commodities, particularly foodstuffs...

, and although they were forcibly suppressed, the planned price increases were canceled. High foreign debts, food shortages, and an outmoded industrial base compelled a new round of economic reforms in 1980. Once again, price increases set off protests across the country, especially in the Gdańsk and Szczecin shipyards. Gierek was forced to grant legal status to Solidarity and to concede the right to strike. (Gdańsk Agreement

Gdansk Agreement

The Gdańsk Agreement was an accord reached as a direct result of the strikes that took place in Gdańsk, Poland...

).

Shortly thereafter, in early September 1980, Gierek was replaced as by Stanisław Kania as General Secretary of the party by the Central Committee, amidst much social and economic unrest.

Kania admitted that the party had made many economic mistakes, and advocated working with Catholic and trade unionist opposition groups. He met with Solidarity Union

Solidarity Union

Solidarity Union is a trade union in New Zealand and was founded in August 2006.The Solidarity Union seeks to organise workers in clusters in South Auckland around an area strategy building local workers councils...

leader Lech Wałęsa

Lech Wałęsa

Lech Wałęsa is a Polish politician, trade-union organizer, and human-rights activist. A charismatic leader, he co-founded Solidarity , the Soviet bloc's first independent trade union, won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1983, and served as President of Poland between 1990 and 95.Wałęsa was an electrician...

, and other critics of the party. Though Kania agreed with his predecessors that the Communist Party must maintain control of Poland, he never assured the Soviets that Poland would not pursue actions independent of the Soviet Union. On October 18, 1981, the Central Committee of the Party withdrew confidence on him, and Kania was replaced by Prime Minister (and Minister of Defence) Gen. Wojciech Jaruzelski

Wojciech Jaruzelski

Wojciech Witold Jaruzelski is a retired Polish military officer and Communist politician. He was the last Communist leader of Poland from 1981 to 1989, Prime Minister from 1981 to 1985 and the country's head of state from 1985 to 1990. He was also the last commander-in-chief of the Polish People's...

.

Jaruzelski's autocratic rule

Prime Minister of the Republic of Poland

The Prime Minister of Poland heads the Polish Council of Ministers and directs their work, supervises territorial self-government within the guidelines and in ways described in the Constitution and other legislation, and acts as the superior for all government administration workers...

and became the First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Polish United Workers Party on October 18 the same year.

Before initiating the plan, he presented it to Soviet Premier Nikolai Tikhonov

Nikolai Tikhonov

Nikolai Aleksandrovich Tikhonov was a Soviet Russian-Ukrainian statesman during the Cold War. He served as Chairman of the Council of Ministers from 1980 to 1985, and as a First Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers, literally First Vice Premier, from 1976 to 1980...

. On 13 December 1981, Jaruzelski imposed martial law in Poland

Martial law in Poland

Martial law in Poland refers to the period of time from December 13, 1981 to July 22, 1983, when the authoritarian government of the People's Republic of Poland drastically restricted normal life by introducing martial law in an attempt to crush political opposition to it. Thousands of opposition...

In 1982 Jaruzelski revitalized the Front of National Unity

Front of National Unity

Front of National Unity or National Unity Front was a Polish communist political organization supervising elections in People's Republic of Poland and also acting as a coalition for the dominant communist Polish United Workers' Party and its allies. It was founded in 1952 as National Front and...

, the organization the Communists used to manage their satellite parties, as the Patriotic Movement for National Rebirth

Patriotic Movement for National Rebirth

Patriotyczny Ruch Odrodzenia Narodowego was a Polish communist organization. It was created in the aftermath of the martial law in Poland...

.

In 1985, Jaruzelski resigned as prime minister and defence minister and became chairman of the Polish Council of State

Polish Council of State

The Council of State of the Republic of Poland was introduced by the 1947 Small Constitution. It consisted of the President of the Republic of Poland, the Marshal and Vicemarshals of Constituent Sejm, President of the Supreme Chamber of Control and could consist of other members...

, a post equivalent to that of president or a dictator

Dictator

A dictator is a ruler who assumes sole and absolute power but without hereditary ascension such as an absolute monarch. When other states call the head of state of a particular state a dictator, that state is called a dictatorship...

, with his power centered on and firmly entrenched in his coterie of "LWP" generals and lower ranks officers of the Polish Communist Army.

The policies of Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev is a former Soviet statesman, having served as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1985 until 1991, and as the last head of state of the USSR, having served from 1988 until its dissolution in 1991...

also stimulated political reform

Reform

Reform means to put or change into an improved form or condition; to amend or improve by change of color or removal of faults or abuses, beneficial change, more specifically, reversion to a pure original state, to repair, restore or to correct....

in Poland. By the close of the tenth plenary session in December 1988, the Communist Party was forced, after strikes

Strike action

Strike action, also called labour strike, on strike, greve , or simply strike, is a work stoppage caused by the mass refusal of employees to work. A strike usually takes place in response to employee grievances. Strikes became important during the industrial revolution, when mass labour became...

, to approach leaders of Solidarity for talks.

From 6 February to 15 April 1989, negotiations were held between 13 working group

Working group

A working group is an interdisciplinary collaboration of researchers working on new research activities that would be difficult to develop under traditional funding mechanisms . The lifespan of the WG can last anywhere between a few months and several years...

s during 94 sessions of the roundtable talks

Polish Round Table Agreement

The Polish Round Table Talks took place in Warsaw, Poland from February 6 to April 4, 1989. The government initiated the discussion with the banned trade union Solidarność and other opposition groups in an attempt to defuse growing social unrest.-History:...

.

These negotiations resulted in an agreement which stated that a great degree of political power would be given to a newly created bicameral legislature. It also created a new post of president

President of the Republic of Poland

The President of the Republic of Poland is the Polish head of state. His or her rights and obligations are determined in the Constitution of Poland....

to act as head of state and chief executive. Solidarity was also declared a legal organization. During the following Polish elections the Communists won 65 percent of the seats in the Sejm

Sejm

The Sejm is the lower house of the Polish parliament. The Sejm is made up of 460 deputies, or Poseł in Polish . It is elected by universal ballot and is presided over by a speaker called the Marshal of the Sejm ....

, though the seats won were guaranteed and the Communists were unable to gain a majority, while 99 out of the 100 seats in the Senate freely contested were won by Solidarity-backed candidates. Jaruzelski won the presidential ballot by one vote.

Jaruzelski was unsuccessful in convincing Wałęsa

Lech Wałęsa

Lech Wałęsa is a Polish politician, trade-union organizer, and human-rights activist. A charismatic leader, he co-founded Solidarity , the Soviet bloc's first independent trade union, won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1983, and served as President of Poland between 1990 and 95.Wałęsa was an electrician...

to include Solidarity in a "grand coalition" with the Communists, and resigned his position of general secretary of the Polish Communist Party. The Communists' two allied parties broke their long-standing alliance, forcing Jaruzelski to appoint Solidarity's Tadeusz Mazowiecki

Tadeusz Mazowiecki

Tadeusz Mazowiecki is a Polish author, journalist, philanthropist and Christian-democratic politician, formerly one of the leaders of the Solidarity movement, and the first non-communist prime minister in Central and Eastern Europe after World War II.-Biography:Mazowiecki comes from a Polish...

as the country's first non-Communist prime minister since 1948. Jaruzelski resigned as Poland's President in 1990, being succeeded by Wałęsa in December.

Dissolution of the PUWP

Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union was the only legal, ruling political party in the Soviet Union and one of the largest communist organizations in the world...

known as the Moscow loan.

The former activists of the PUWP established the Social Democracy of the Republic of Poland

Social Democracy of the Republic of Poland

Social Democracy of the Republic of Poland was a social-democratic political party in Poland created in 1990, shortly after the Revolutions of 1989. The party was one of two successor parties to the Polish United Workers Party, the other being the Social Democratic Union. SdRP was the leading...

(in Polish: Socjaldemokracja Rzeczpospolitej Polskiej, SdRP), of which the main organizers were Leszek Miller

Leszek Miller

Leszek Cezary Miller is a Polish central-left-wing politician, leader of the Democratic Left Alliance , Prime Minister of the government of the Republic of Poland in 2001-2004.-Childhood and youth:...

and Mieczysław Rakowski. The SdRP was supposed (among other things) to take over all rights and duties of the PUWP, and help to divide out the property of the former PUWP. Up to the end of ‘80s, it had considerable incomes mainly from managed properties and from the RSW company ‘Press- Book-Traffic’, which in turn had special tax concessions. During this period, the incomes from membership fees constituted only 30% of the PUWP's revenues. After the dissolution of the PUWP and the establishment of the SdRP, the rest of the activists formed the Social Democratic Union of the Republic of Poland (USdRP), which changed its name to the Polish Social Democratic Union, and The 8th July Movement.

At the end of 1990, there was an intense debate in the Sejm on the takeover of the wealth that belonged to the former PUWP. Over 3000 buildings and premises were included in the wealth and almost half of it was used without legal basis. Supporters of the acquisition argued that the wealth was built on the basis of plunder and the Treasury grant collected by the whole society. Opponents of SdRP (Social Democratic Party of the Republic of Poland) claimed that the wealth was created from membership fees; therefore, they demanded wealth inheritance for SdPR which at that time administered the wealth. Personal property and the accounts of the former PUWP were not subject to control of a parliamentary committee.

On 9 November 1990, the Sejm passed "The resolution about the acquisition of the wealth that belonged to the former PUWP". This resolution was supposed to result in a final takeover of the PUWP real estate by the Treasury. As a result, only a part of the real estate was taken over mainly for a local government by 1992, whereas a legal dispute over the other party carried on till 2000. Personal property and finances of the former PUWP practically disappeared. According to the declaration of SdRP MP's, 90-95% of the party's wealth was allocated for gratuity or was donated for a social assistance.

Party Congresses

- I founding Congress of PZPR, 15–22 December 1948

- II PUWP Congress, 10–17 March 1954

- III PUWP Congress, 10–19 March 1959

- IV PUWP Congress, 15–20 June 1964

- V PUWP Congress, 11–16 November 1968

- VI PUWP Congress, 6–11 November 1971

- VII PUWP Congress, 8–12 December 1975

- VIII PUWP Congress, 11–15 February 1980

- IX Extraordinary PUWP Congress, 14–20 July 1981

- X PUWP Congress, 29 June - 3 July 1986

- XI PUWP Congress, 27–30 January 1990 (concluded with self-dissolution)

Consequently, in second circulation a banknote with a printed inscription appeared: The last P.Z.P.R Congress closed the proceedings – "Workers of the World, forgive me". Near the inscriptions there is also an image of Lenin praying with rosary.

Building

The Central Committee had its seat in the Party's House, a building erected by obligatory subscription from 1948 to 1952 and coloquially called White House or the House of Sheep. Since 1991 the Bank-Financial Center "New World" is located in this building. In 1991-2000 the Warsaw Stock ExchangeWarsaw Stock Exchange

The Warsaw Stock Exchange , , is a stock exchange located in Warsaw, Poland. It has a capitalization of € 220 bln .The WSE is a member of the World Federation of Exchanges and the Federation of European Securities Exchanges.-History:...

had also its seat in this building.

Party leaders

By the year 1954 the head of the party was the Chair of Central Committee:| # | Name | Picture | Took office | Left office | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bolesław Bierut | December 22, 1948 | March 12, 1956 | Secretary General | |

| 2 | Edward Ochab Edward Ochab Edward Ochab was a Polish Communist politician promoted to the position of the First Secretary of the Communist party in the People's Republic of Poland between 20 March and 21 October 1956, just prior to the Gomułka thaw... |

.jpg) |

March 20, 1956 | October 21, 1956 | First Secretary |

| 3 | Władysław Gomułka | October 21, 1956 | December 20, 1970 | First Secretary | |

| 4 | Edward Gierek Edward Gierek Edward Gierek was a Polish communist politician.He was born in Porąbka, outside of Sosnowiec. He lost his father to a mining accident in a pit at the age of four. His mother married again and emigrated to northern France, where he was raised. He joined the French Communist Party in 1931 and was... |

|

December 20, 1970 | September 6, 1980 | First Secretary |

| 5 | Stanisław Kania | September 6, 1980 | October 18, 1981 | First Secretary | |

| 6 | Wojciech Jaruzelski Wojciech Jaruzelski Wojciech Witold Jaruzelski is a retired Polish military officer and Communist politician. He was the last Communist leader of Poland from 1981 to 1989, Prime Minister from 1981 to 1985 and the country's head of state from 1985 to 1990. He was also the last commander-in-chief of the Polish People's... |

October 18, 1981 | July 29, 1989 | First Secretary | |

| 7 | Mieczysław Rakowski | July 29, 1989 | January 29, 1990 | First Secretary | |

Leading figures of the PUWP

- Jerzy Albrecht

- Edward BabiuchEdward BabiuchEdward Babiuch was a Polish Communist political figure. He was one of four deputy chairmen of the Polish Council of State 1976–1980. Babiuch briefly served as the Prime Minister of Poland in 1980, from February 18 to August 24 of that year.-References:...

- Kazimierz BarcikowskiKazimierz BarcikowskiKazimierz Barcikowski was a Polish politician. Member of Polish United Workers Party, served on the Central Committee of the Party and on Political Bureau. Among his other posts were those of deputy to Sejm and minister of agriculture. Head of government negotiations with striking workers in...

- Jakub BermanJakub BermanJakub Berman was born into a middle-class Jewish family. Berman first became a prominent communist in prewar Poland. Toward the end of World War II he joined the Politburo of the Soviet-formed Polish United Workers' Party...

- Józef CyrankiewiczJózef CyrankiewiczJózef Cyrankiewicz was a Polish Socialist, after 1948 Communist political figure. He served as premier of the People's Republic of Poland between 1947 and 1952, and again between 1954 and 1970...

- Zdzisław Grudzień

- Mieczysław Jagielski

- Piotr JaroszewiczPiotr JaroszewiczGen. Piotr Jaroszewicz was a Polish Communist political figure. He served as the Prime Minister of Poland between 1970 and 1980.Piotr Jaroszewicz was born on 8 October 1909 in Nieśwież. After finishing the secondary school in Jasło he started working as a teacher and headmaster in Garwolin...

- Bolesław Jaszczuk

- Stefan Jędrychowski

- Aleksander KwaśniewskiAleksander KwasniewskiAleksander Kwaśniewski is a Polish politician who served as the President of Poland from 1995 to 2005. He was born in Białogard, and during communist rule he was active in the Socialist Union of Polish Students and was the Minister for Sport in the communist government in the 1980s...

- Zenon Kliszko

- Stanisław Kociołek

- Jerzy Łukaszewicz

- Franciszek Mazur

- Zbigniew MessnerZbigniew MessnerZbigniew Messner was a Communist economist and politician in Poland. In 1972, he became Professor of Karol Adamiecki University of Economics in Katowice...

- Hilary MincHilary MincHilary Minc – born into a middle-class Jewish family of Oskar Minc and Stefania née Fajersztajn – was a communist politician in Stalinist Poland and pro-Soviet Marxist economist. Minc joined the Communist Party of Poland before World War II...

- Mieczysław Moczar

- Kazimierz Morawski

- Zenon NowakZenon NowakZenon Nowak was a Communist activist and politician in the People's Republic of Poland. One of the members of the pro-Soviet Natolin faction of the PZPR Central Committee during the Polish October of 1956.-References:...

- Józef OleksyJózef OleksyJózef Oleksy is a post-communist Polish politician, former chairman of Democratic Left Alliance ....

- Stefan Olszowski

- Józef PińkowskiJózef PinkowskiJózef Pińkowski was a Polish Communist politician who served as Prime Minister from 1980 to 1981....

- Stanisław RadkiewiczStanisław RadkiewiczStanisław Radkiewicz was a Polish communist activist with Soviet citizenship, member of the pre-war Communist Party of Poland and of the post-war Polish United Workers' Party...

- Ignacy Loga-Sowiński

- Ryszard Strzelecki

- Józef Tejchma

- Roman ZambrowskiRoman ZambrowskiRoman Zambrowski was a Polish communist activist. He is a father of journalist Antoni Zambrowski....

- Aleksander ZawadzkiAleksander ZawadzkiAleksander Zawadzki was a Polish Communist political figure and head of state of Poland from 1952 to 1964.A member of the Communist Youth Union, Zawadzki went into exile in the Soviet Union in 1931, after spending six years in prison for "subversive activities." He returned to Poland in 1939, just...

Prime ministers

- Józef OleksyJózef OleksyJózef Oleksy is a post-communist Polish politician, former chairman of Democratic Left Alliance ....

- Włodzimierz Cimoszewicz

- Leszek MillerLeszek MillerLeszek Cezary Miller is a Polish central-left-wing politician, leader of the Democratic Left Alliance , Prime Minister of the government of the Republic of Poland in 2001-2004.-Childhood and youth:...

- Marek BelkaMarek BelkaMarek Marian Belka is a Polish professor of Economics, a former Prime Minister and Finance Minister of Poland, former Director of the International Monetary Fund's European Department and current Head of National Bank of Poland.- Biography :...

See also

- Politburo of the Polish United Workers' PartyPolitburo of the Polish United Workers' PartyThe Politburo of the Polish United Workers Party was the chief executive body of the ruling Polish Communist apparatus between 1948–1989. Nearly all key figures of the regime had membership in the Politburo. The Politburo of the PUWP typically had between 9-15 full members at any one time...

- List of Polish United Workers' Party members

- Eastern Bloc politicsEastern Bloc politicsEastern Bloc politics followed the Red Army's occupation of much of eastern Europe at the end of World War II and the Soviet Union's installation of Soviet-controlled communist governments in the Eastern Bloc through a process of bloc politics and repression...