Timeline of children's rights in the United Kingdom

Encyclopedia

The timeline of children's rights

in the United Kingdom includes a variety of events that are both political and grassroots

in nature.

The UK government maintains a position that UNCRC is not legally enforceable and is hence 'aspirational' only, although a 2003 ECHR ruling states that, "The human rights of children and the standards to which all governments must aspire in realising these rights for all children are set out in the Convention on the Rights of the Child." Eighteen years after ratification, the four Children's Commissioners in the UK (including those for the three devolved administrations) have united in calling for adoption of the Convention into domestic legislation, making children's rights recognised and legally binding.

Opponents of children's rights often raise the spectre of rights

without responsibilities

. The children's rights movement

asserts rather that children have rights which adults, states and the government have a responsibility to uphold. Overall, a 2008 report stated that there had been no improvement in children's rights in the UK since 2002. Warning that there is a "widely held fear of children

and young people" in the UK, the report says: "The incessant portrayal of children as thugs and yobs" not only reinforces the fears of the public but also influences policy and legislation."

The UNCRC defines children, for the purposes of the Convention, as persons under the age 18, unless domestic legislation provides otherwise. In that spirit, this timeline includes as children all those below the UK age of majority, which was 21 until 1971, when it was reduced to 18. Although the Crown Dependencies of the Isle of Man

, Guernsey

and Jersey

are not constitutionally part of the UK, the British government is responsible for their external affairs and therefore for their international treaty obligations, so this timeline includes some references to matters in those dependencies.

Children's rights

Children's rights are the human rights of children with particular attention to the rights of special protection and care afforded to the young, including their right to association with both biological parents, human identity as well as the basic needs for food, universal state-paid education,...

in the United Kingdom includes a variety of events that are both political and grassroots

Grassroots

A grassroots movement is one driven by the politics of a community. The term implies that the creation of the movement and the group supporting it are natural and spontaneous, highlighting the differences between this and a movement that is orchestrated by traditional power structures...

in nature.

The UK government maintains a position that UNCRC is not legally enforceable and is hence 'aspirational' only, although a 2003 ECHR ruling states that, "The human rights of children and the standards to which all governments must aspire in realising these rights for all children are set out in the Convention on the Rights of the Child." Eighteen years after ratification, the four Children's Commissioners in the UK (including those for the three devolved administrations) have united in calling for adoption of the Convention into domestic legislation, making children's rights recognised and legally binding.

Opponents of children's rights often raise the spectre of rights

Rights

Rights are legal, social, or ethical principles of freedom or entitlement; that is, rights are the fundamental normative rules about what is allowed of people or owed to people, according to some legal system, social convention, or ethical theory...

without responsibilities

Social responsibility

Social responsibility is an ethical ideology or theory that an entity, be it an organization or individual, has an obligation to act to benefit society at large. Social responsibility is a duty every individual or organization has to perform so as to maintain a balance between the economy and the...

. The children's rights movement

Children's rights movement

The Children's Rights Movement is a historical and modern movement committed to the acknowledgment, expansion, and/or regression of the rights of children around the world...

asserts rather that children have rights which adults, states and the government have a responsibility to uphold. Overall, a 2008 report stated that there had been no improvement in children's rights in the UK since 2002. Warning that there is a "widely held fear of children

Fear of children

Fear of children, fear of infants or fear of childhood is alternatively called pedophobia, paedophobia or pediaphobia. Other age-focused fears are ephebiphobia and gerontophobia...

and young people" in the UK, the report says: "The incessant portrayal of children as thugs and yobs" not only reinforces the fears of the public but also influences policy and legislation."

The UNCRC defines children, for the purposes of the Convention, as persons under the age 18, unless domestic legislation provides otherwise. In that spirit, this timeline includes as children all those below the UK age of majority, which was 21 until 1971, when it was reduced to 18. Although the Crown Dependencies of the Isle of Man

Isle of Man

The Isle of Man , otherwise known simply as Mann , is a self-governing British Crown Dependency, located in the Irish Sea between the islands of Great Britain and Ireland, within the British Isles. The head of state is Queen Elizabeth II, who holds the title of Lord of Mann. The Lord of Mann is...

, Guernsey

Guernsey

Guernsey, officially the Bailiwick of Guernsey is a British Crown dependency in the English Channel off the coast of Normandy.The Bailiwick, as a governing entity, embraces not only all 10 parishes on the Island of Guernsey, but also the islands of Herm, Jethou, Burhou, and Lihou and their islet...

and Jersey

Jersey

Jersey, officially the Bailiwick of Jersey is a British Crown Dependency off the coast of Normandy, France. As well as the island of Jersey itself, the bailiwick includes two groups of small islands that are no longer permanently inhabited, the Minquiers and Écréhous, and the Pierres de Lecq and...

are not constitutionally part of the UK, the British government is responsible for their external affairs and therefore for their international treaty obligations, so this timeline includes some references to matters in those dependencies.

Pre-19th century

| Timeline of pre-19th century events related to Children's Rights in the UK in chronological order | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Parties | Event | Image |

| Pre-16th century | The care of orphans Orphanage An orphanage is a residential institution devoted to the care of orphans – children whose parents are deceased or otherwise unable or unwilling to care for them... was particularly commended to bishops and monasteries during the Middle Ages. Many orphanages practised some form of "binding-out" in which children, as soon as they were old enough, were given as apprentices to households to ensure their support and their learning an occupation. Common law Common law Common law is law developed by judges through decisions of courts and similar tribunals rather than through legislative statutes or executive branch action... maintaining the King's peace Queen's peace The Queen's peace is the term used in the Commonwealth realms to describe the protection the monarch, in right of each state, provides to his or her subjects... was administered by the Court of Common Pleas (England) Court of Common Pleas (England) The Court of Common Pleas, or Common Bench, was a common law court in the English legal system that covered "common pleas"; actions between subject and subject, which did not concern the king. Created in the late 12th to early 13th century after splitting from the Exchequer of Pleas, the Common... dealing with civil cases between parties Party (law) A party is a person or group of persons that compose a single entity which can be identified as one for the purposes of the law. Parties include: plaintiff , defendant , petitioner , respondent , cross-complainant A party is a person or group of persons that compose a single entity which can be... by ordering the fine of debts and seizure of the goods of outlaws. Following the Peasants' Revolt Peasants' Revolt The Peasants' Revolt, Wat Tyler's Rebellion, or the Great Rising of 1381 was one of a number of popular revolts in late medieval Europe and is a major event in the history of England. Tyler's Rebellion was not only the most extreme and widespread insurrection in English history but also the... , British constables were authorised under a 1383 statute to collar vagabond Vagabond (person) A vagabond is a drifter and an itinerant wanderer who roams wherever they please, following the whim of the moment. Vagabonds may lack residence, a job, and even citizenship.... s and force them to show their means of support; if they could not, the penalty was gaol. Under a 1494 statute, vagabonds could be sentenced to the stocks for three days and nights; in 1530, whipping was added. The assumption was that vagabonds were unlicenced beggars. |

||

| January 1561 | Scotland | The national Church of Scotland Church of Scotland The Church of Scotland, known informally by its Scots language name, the Kirk, is a Presbyterian church, decisively shaped by the Scottish Reformation.... set out a programme for spiritual reform, setting the principle of a school teacher History of education The history of education its part of the past and present teaching and learning. Each generation, since the beginning of human existence, has sought to pass on cultural and social values, traditions, morality, religion and skills to the next generation. The passing on of culture is also known as... for every parish church and free education Free education Free education refers to education that is funded through taxation, or charitable organizations rather than tuition fees. Although primary school and other comprehensive or compulsory education is free in many countries, for example, all education is mostly free including... . This was provided for by an Act of the Parliament of Scotland Parliament of Scotland The Parliament of Scotland, officially the Estates of Parliament, was the legislature of the Kingdom of Scotland. The unicameral parliament of Scotland is first found on record during the early 13th century, with the first meeting for which a primary source survives at... , passed in 1633, which introduced a tax to pay for this programme. |

|

| 1367–1607 | Ireland | Suppression of the Brehon Laws Brehon Laws Early Irish law refers to the statutes that governed everyday life and politics in Early Medieval Ireland. They were partially eclipsed by the Norman invasion of 1169, but underwent a resurgence in the 13th century, and survived into Early Modern Ireland in parallel with English law over the... which enumerated the rights and responsibilities of fostered children, their birth-parents and foster-parents. The Brehon Law concept of family was eroded and the Gaelic tradition of fosterage Fosterage Fosterage, the practice of a family bringing up a child not their own, differs from adoption in that the child's parents, not the foster-parents, remain the acknowledged parents. In many modern western societies foster care can be organised by the state to care for children with troubled family... lost. It was ultimately replaced by the State controlled Poor Law system Irish Poor Laws The Irish Poor Laws were a series of Acts of Parliament intended to address social instability due to widespread and persistent poverty in Ireland. While some legislation had been introduced by the pre-Union Parliament of Ireland prior to the Act of Union, the most radical and comprehensive... . |

|

| 1601 | Elizabethan Poor Law Poor Law The English Poor Laws were a system of poor relief which existed in England and Wales that developed out of late-medieval and Tudor-era laws before being codified in 1587–98... |

The Poor Law was the social security system operating in England and Wales from the 16th century until the establishment of the Welfare State in the 20th century. The Impotent poor was a classification of poverty used to refer to those poor considered deserving of poor relief; a vagrant Vagrancy (people) A vagrant is a person in poverty, who wanders from place to place without a home or regular employment or income.-Definition:A vagrant is "a person without a settled home or regular work who wanders from place to place and lives by begging;" vagrancy is the condition of such persons.-History:In... was a person who could work, but preferred not to. The law did not distinguish between the impotent poor and the criminal, so both received the same punishments. The law provided for "the putting out of children to be apprentices". |

|

| 17th Century | Where an unmarried mother concealed the death of her baby, she was presumed guilty of infanticide Infanticide Infanticide or infant homicide is the killing of a human infant. Neonaticide, a killing within 24 hours of a baby's birth, is most commonly done by the mother.In many past societies, certain forms of infanticide were considered permissible... unless she could prove that the baby was born dead (this requirement that the defendant prove her innocence was a reversal of the normal practice of requiring the prosecution to prove the defendant's guilt). Women were acquitted of this charge if they could demonstrate that they had prepared for the birth of the baby, for example by acquiring some kind of bedding. In 1678 children aged 10 were deemed able to engage in consensual sex. |

||

| 1732–1744 | Bastard Legitimacy (law) At common law, legitimacy is the status of a child who is born to parents who are legally married to one another; and of a child who is born shortly after the parents' divorce. In canon and in civil law, the offspring of putative marriages have been considered legitimate children... y |

In 1732, a woman pregnant with a "bastard Legitimacy (law) At common law, legitimacy is the status of a child who is born to parents who are legally married to one another; and of a child who is born shortly after the parents' divorce. In canon and in civil law, the offspring of putative marriages have been considered legitimate children... " was required to declare the fact and to name the father. In 1733, the putative father became responsible for maintaining his illegitimate child; failing to do so could result in gaol. The parish would then support the mother and child, until the father agreed to do so, whereupon he would reimburse the parish — although this rarely happened. In 1744, a bastard took the 'settlement' of its mother (under the Poor Law Poor Law The English Poor Laws were a system of poor relief which existed in England and Wales that developed out of late-medieval and Tudor-era laws before being codified in 1587–98... , a person's place of origin or later established residence, being the Parish responsible for the person if destitute) regardless of where the child was actually born. Previously, a bastard took settlement Poor Relief Act 1662 The Poor Relief Act 1662 was an Act of the Cavalier Parliament of England. It was an Act for the Better Relief of the Poor of this Kingdom and is also known as the Settlement Act or, more honestly, the Settlement and Removal Act. The purpose of the Act was to establish the parish to which a person... from its place of birth. The mother was to be publicly whipped. |

|

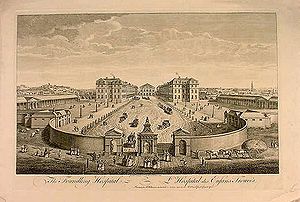

| 1739 | The Foundling Hospital Foundling Hospital The Foundling Hospital in London, England was founded in 1741 by the philanthropic sea captain Thomas Coram. It was a children's home established for the "education and maintenance of exposed and deserted young children." The word "hospital" was used in a more general sense than it is today, simply... |

Established in London by the philanthropic Philanthropy Philanthropy etymologically means "the love of humanity"—love in the sense of caring for, nourishing, developing, or enhancing; humanity in the sense of "what it is to be human," or "human potential." In modern practical terms, it is "private initiatives for public good, focusing on quality of... sea captain Thomas Coram as a home for the "education and maintenance of exposed and deserted young children." Children were seldom taken after they were twelve months old. On reception they were sent to wet nurse Wet nurse A wet nurse is a woman who is used to breast feed and care for another's child. Wet nurses are used when the mother is unable or chooses not to nurse the child herself. Wet-nursed children may be known as "milk-siblings", and in some cultures the families are linked by a special relationship of... s in the countryside, where they stayed until they were about four or five years old. At sixteen girls were generally apprenticed as servants for four years; at fourteen, boys became apprentices in varying occupations for seven years. |

|

| 1779 | The Penitentiary Act Penitentiary Act The Penitentiary Act was a British Act of Parliament passed in 1779 which introduced state prisons for the first time. The Act was drafted by the prison reformer John Howard and the jurist William Blackstone and recommended imprisonment as an alternative sentence to death or transportation.The... |

Drafted by Prison reform Prison reform Prison reform is the attempt to improve conditions inside prisons, aiming at a more effective penal system.-History:Prisons have only been used as the primary punishment for criminal acts in the last couple of centuries... er John Howard John Howard John Winston Howard AC, SSI, was the 25th Prime Minister of Australia, from 11 March 1996 to 3 December 2007. He was the second-longest serving Australian Prime Minister after Sir Robert Menzies.... , the Act introduced state prisons as an alternative to the death penalty or transportation. The prison population had risen after the US Declaration of Independence, because the American Colonies had been used as the destination for transported criminals. Howard's 1777 report had identified appalling conditions in most of the prisons he inspected. The Howard League for Penal Reform Howard League for Penal Reform The Howard League for Penal Reform is a London-based registered charity in the United Kingdom. It is the oldest penal reform organisation in the world, named after John Howard. Founded in 1866 as the Howard Association, a merger with the Penal Reform League in 1921 created the Howard League for... emerged as a result, publishing in 2006 the findings of an independent inquiry by Lord Carlile of Berriew QC into physical restraint, solitary confinement and forcible strip searching of children in prisons, secure training centres and local authority secure children's homes. |

|

| 1795 | Speenhamland system | An amendment to the Poor Law, named after a meeting at the Pelican Inn in Speenhamland, Berkshire, where the local magistrates or squire Squire The English word squire is a shortened version of the word Esquire, from the Old French , itself derived from the Late Latin , in medieval or Old English a scutifer. The Classical Latin equivalent was , "arms bearer"... archy devised the system as a means to alleviate hardship caused by a spike in grain prices. Families were paid extra to top up wages to a set level, which varied according to the number of children and the price of bread. For example if bread was 1s 2d a loaf, the wages of a family with two children was topped up to 8s 6d. If bread rose to 1s 8d the wages were topped up to 11s 0d. The system aggravated the underlying causes of poverty, allowing employers (often farmers) to pay below subsistence wages, because the parish made up the difference to keep their workers alive. Low incomes remained unchanged and the poor rate contributors subsidised the farmers, so that landowners sought other means of dealing with the poor e.g. the workhouse Workhouse In England and Wales a workhouse, colloquially known as a spike, was a place where those unable to support themselves were offered accommodation and employment... . The Poor Law Commissioners' Report of 1834 called the Speenhamland System a "universal system of pauperism." |

|

| 1796 | Thomas Spence Thomas Spence Thomas Spence was an English Radical and advocate of the common ownership of land.-Life:Spence was born in Newcastle-on-Tyne, England and was the son of a Scottish net and shoe maker.... |

Publication of The Rights of Infants by the revolutionary philosopher.http://thomas-spence-society.co.uk/4.html |  |

19th century

| Timeline of 19th century events related to Children's Rights in the UK in chronological order | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Parties | Event | Image | ||||

| 1802 | UK Parliament | The Factory Acts Factory Acts The Factory Acts were a series of Acts passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom to limit the number of hours worked by women and children first in the textile industry, then later in all industries.... were a series of Acts of Parliament passed to limit the number of hours worked by women and children, first in the textile industry, then later in all industries. The Factories Act 1802, sometimes also called the "Health and Morals of Apprentices Act," sought to regulate factory conditions, especially in regard to child workers. It was the culmination of a movement originating in the 18th century, where reformers had tried to push several acts through Parliament to improve the health of workers and children. |

|||||

| 1806 | Philanthropic Society Royal Philanthropic Society The Royal Philanthropic Society had its origins in the St Paul's Coffee House in London in 1788 where a group of men met to discuss the problems of homeless children who were to be found begging and stealing on the streets. The Society began by opening homes where children were trained in cottage... |

The Society was incorporated by Act of Parliament, sanctioning its work with juvenile delinquents and began by opening homes where children were trained in cottage industries working under the instruction of skilled tradesmen. Remaining central in development of measures dealing with young offenders the Society is now the charity, Catch 22, formerly Rainer. | |||||

| 1818 | Ragged Schools | A cobbler, John Pounds, began to use his shop in Portsmouth as a base for educational activity for local poor children neglected by other institutions. Part of his concern was also to educate his disabled nephew. The Ragged School movement subsequently found powerful support in active philanthropists when public attention was aroused to the prevalence of juvenile delinquency by Thomas Guthrie Thomas Guthrie Thomas Guthrie D.D. was a Scottish divine and philanthropist, born at Brechin in Angus . He was one of the most popular preachers of his day in Scotland, and was associated with many forms of philanthropy - especially temperance and Ragged Schools, of which he was a founder.He studied at Edinburgh... in 1840. An estimated 300,000 children passed through the London Ragged Schools alone between the early 1840s and 1881 |

|||||

| 1818 | Elizabeth Fry Elizabeth Fry Elizabeth Fry , née Gurney, was an English prison reformer, social reformer and, as a Quaker, a Christian philanthropist... |

After visiting Newgate Prison Newgate Prison Newgate Prison was a prison in London, at the corner of Newgate Street and Old Bailey just inside the City of London. It was originally located at the site of a gate in the Roman London Wall. The gate/prison was rebuilt in the 12th century, and demolished in 1777... , Fry became particularly concerned at the conditions in which women prisoners and their children were held. Fry later presented evidence to the House of Commons in 1818, which led to the interior of Newgate Newgate Newgate at the west end of Newgate Street was one of the historic seven gates of London Wall round the City of London and one of the six which date back to Roman times. From it a Roman road led west to Silchester... being rebuilt with individual cells. |

|

||||

| 1834 | Workhouse Workhouse In England and Wales a workhouse, colloquially known as a spike, was a place where those unable to support themselves were offered accommodation and employment... |

The workhouse system was set up in England and Wales under the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834, although many individual houses existed before this legislation. Inmates entered and left as they liked and would receive free food and accommodation. However, workhouse life was made as harsh and degrading as possible so that only the truly destitute would apply. Accounts of the terrible conditions in some workhouses include references to women who would not speak and children who refused to play. | |||||

| 1838 | Charles Dickens Charles Dickens Charles John Huffam Dickens was an English novelist, generally considered the greatest of the Victorian period. Dickens enjoyed a wider popularity and fame than had any previous author during his lifetime, and he remains popular, having been responsible for some of English literature's most iconic... |

Oliver Twist Oliver Twist Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress is the second novel by English author Charles Dickens, published by Richard Bentley in 1838. The story is about an orphan Oliver Twist, who endures a miserable existence in a workhouse and then is placed with an undertaker. He escapes and travels to... , Dickens' second novel, is the first in the English language to centre upon a child protagonist throughout. The book calls attention to various contemporary social evils, including the Poor Law Poor Law The English Poor Laws were a system of poor relief which existed in England and Wales that developed out of late-medieval and Tudor-era laws before being codified in 1587–98... , which required that poor people work in workhouse Workhouse In England and Wales a workhouse, colloquially known as a spike, was a place where those unable to support themselves were offered accommodation and employment... s, child labour and the recruitment of children as criminals Juvenile delinquency Juvenile delinquency is participation in illegal behavior by minors who fall under a statutory age limit. Most legal systems prescribe specific procedures for dealing with juveniles, such as juvenile detention centers. There are a multitude of different theories on the causes of crime, most if not... . A later character, Jo in Bleak House Bleak House Bleak House is the ninth novel by Charles Dickens, published in twenty monthly installments between March 1852 and September 1853. It is held to be one of Dickens's finest novels, containing one of the most vast, complex and engaging arrays of minor characters and sub-plots in his entire canon... , is portrayed as a street child Street Child Street Child is a debut album by Mexican alternative rock vocalist, Elan. It contains her biggest hit, Midnight.Ricardo Burgos from Sony Music called Street Child "a history making release in Latin America".-Re-edition track listing:... , relentlessly pursued by a police inspector. |

|||||

| 1839 | Custody of Infants Act | Custody of children under 7 years old was assigned to mothers | |||||

| 1840 | Mettray Penal Colony Mettray Penal Colony Mettray Penal Colony, situated in the small village of Mettray, in the French département of Indre-et-Loire, just north of the city of Tours, was a private reformatory, without walls, opened in 1840 for the rehabilitation of young male delinquents aged between 6 and 21. At that time children and... |

In Mettray, north of the city of Tours, France a private reformatory, without walls, was opened by penal reformer Frédéric-Auguste Demetz in 1840 for the rehabilitation of young males aged between 6 and 21. At that time children and teenagers were routinely imprisoned with adults. Boys who were mostly deprived, disadvantaged or adandoned children, many of whom had committed only Summary offence Summary offence A summary offence is a criminal act in some common law jurisdictions that can be proceeded with summarily, without the right to a jury trial and/or indictment .- United States :... s or petty crime, were housed. Their heads were shaved, they wore uniforms, and up to age 12 spent most of the day studying arithmetic, writing and reading. Older boys had one hour of classes, with the rest of the day spent working. Reformatory Schools were modelled on Mettray, and the Borstal Borstal A borstal was a type of youth prison in the United Kingdom, run by the Prison Service and intended to reform seriously delinquent young people. The word is sometimes used loosely to apply to other kinds of youth institution or reformatory, such as Approved Schools and Detention Centres. The court... system, established in 1905, separated adolescents from adult prisoners. In the twentieth century Mettray became the focus for Michel Foucault Michel Foucault Michel Foucault , born Paul-Michel Foucault , was a French philosopher, social theorist and historian of ideas... because of its various systems and expressions of power and led Foucault to suggest that Mettray began the descent into modern penal theories and their inherent power structures. |

|

||||

| 1847 | Juvenile Offenders Act | The Act allowed children under the age of fourteen to be tried summarily before two magistrates, speeding up the process of trial for children, and removing it from the publicity of the higher courts. The age limit was raised to sixteen in 1850. | |||||

| 1850 | Irish Workhouse Returns, 8 June 1850. | The number of children aged 15 years and younger in Irish Workhouses reaches its historic high, at 115,639. | |||||

| 1854 | Reformatory Schools | Mary Carpenter Mary Carpenter Mary Carpenter was an English educational and social reformer. The daughter of a Unitarian minister, she founded a ragged school and reformatories, bringing previously unavailable educational opportunities to poor children and young offenders in Bristol.She published articles and books on her work... 's research and lobbying contributed to the Youthful Offenders Act 1854 and the Reformatory Schools (Scotland) Act 1854. These enabled voluntary schools to be certified as efficient by the Inspector of Prisons, and allowed courts to send them convicted juvenile offenders under 16 for a period of 2 to 5 years, instead of prison. Parents were required to contribute to the cost. Carpenter's 1851 publication Reformatory Schools for the Children of the Perishing and Dangerous Classes and for Juvenile Offenders was the first to coin the term 'Dangerous Classes' with respect to the lower classes, and the perceived propensity to criminality, of poor people. |

|||||

| 1857 | Industrial School Industrial school In Ireland the Industrial Schools Act of 1868 established industrial schools to care for "neglected, orphaned and abandoned children". By 1884 there were 5,049 children in such institutions.... s |

The Industrial Schools Act 1857 allowed magistrates to send disorderly children to a residential industrial school, resolving the problems of juvenile delinquency Juvenile delinquency Juvenile delinquency is participation in illegal behavior by minors who fall under a statutory age limit. Most legal systems prescribe specific procedures for dealing with juveniles, such as juvenile detention centers. There are a multitude of different theories on the causes of crime, most if not... by removing poor and neglected children from their home environment into a boarding school. An 1876 Act led to non-residential day schools of a similar kind. In 1986 Professor Sir Leon Radzinowitz noted the practice of Economic conscription Economic conscription Economic conscription is a term used to describe mechanisms for recruitment of personnel for the armed forces through the use of economic conditions... , where, ‘there was a network of 208 schools: 43 reformatories, 132 industrial schools, 21 day industrial schools and 12 truant schools’ by the eve of the First World War, alongside a negligible education system for the poor. |

|||||

| 1870 | UK Government | Prior to the Elementary Education Act 1870 Elementary Education Act 1870 The Elementary Education Act 1870, commonly known as Forster's Education Act, set the framework for schooling of all children between ages 5 and 12 in England and Wales... act, very few schools existed, other than those run by the Church. The National Education League National Education League The National Education League was a political movement in England and Wales which promoted elementary education for all children, free from religious control.... was established to promote elementary education for all children, free from religious control. The Act first introduced and enforced compulsory school attendance Compulsory education Compulsory education refers to a period of education that is required of all persons.-Antiquity to Medieval Era:Although Plato's The Republic is credited with having popularized the concept of compulsory education in Western intellectual thought, every parent in Judea since Moses's Covenant with... between the ages of 5 and 12, with school boards set up to ensure that children attended school; although exemptions were made for illness and travelling distance. The London School Board London School Board The School Board for London was an institution of local government and the first directly elected body covering the whole of London.... was highly influential and launched a number of political careers. The Church/State ethical divide in schooling, persists into the present day. |

|

||||

| 1870 | Thomas John Barnado | The first of 112 Barnardo's Barnardo's Barnardo's is a British charity founded by Thomas John Barnardo in 1866, to care for vulnerable children and young people. As of 2010, it spends over £190 million each year on more than 400 local services aimed at helping these same groups... Homes was founded, with destitution as the criterion for qualification. The project was supported by the seventh Earl of Shaftesbury Earl of Shaftesbury Earl of Shaftesbury is a title in the Peerage of England. It was created in 1672 for Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 1st Baron Ashley, a prominent politician in the Cabal then dominating the policies of King Charles II... and the first Earl Cairns Earl Cairns Earl Cairns is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1878 for the prominent lawyer and Conservative politician Hugh Cairns, 1st Baron Cairns. He was Lord Chancellor of the United Kingdom in 1868 and from 1874 to 1880... . The system of operation was broadly as follows: infants and younger girls and boys are chiefly "boarded out" in rural districts; girls above 14 years of age are sent to 'industrial training homes' to be taught useful domestic occupations; boys above 17 years old are first tested in labour homes and then placed in employment at home, sent to sea or emigrated; boys between 13 – 17 years old were trained for trades for which they may be mentally or physically fitted. |

|

||||

| 1880 | UK Government | Following campaigning by the National Education League National Education League The National Education League was a political movement in England and Wales which promoted elementary education for all children, free from religious control.... the Elementary Education Act 1880 Elementary Education Act 1880 The Elementary Education Act 1880 was a British Act of Parliament which extended the Elementary Education Act 1870. The act extended the compulsory age of attendance at school until the age of 10.... made schooling compulsory until the age of ten and also established attendance officers to enforce attendance, so that parents who objected to compulsory education, arguing they needed children to earn a wage, could be fined for keeping their children out of school. School leaving age was raised with successive Acts from ten to age fourteen in 1918. |

|||||

| 1885 | UK Government | Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885 Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885 The Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885 , or "An Act to make further provision for the Protection of Women and Girls, the suppression of brothels, and other purposes", was the latest in a 25-year series of legislation in the United Kingdom beginning with the Offences against the Person Act 1861 that... raises age of consent from 13 to 16, introduced measures intended to protect girls from sexual exploitation and criminalises male homosexual behaviour Labouchere Amendment The Labouchere Amendment, also known as Section 11 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885 made gross indecency a crime in the United Kingdom. The amendment gave no definition of "gross indecency," as Victorian morality demurred from precise descriptions of activity held to be immoral... . |

|||||

| 1891 | UK Government | The practice of 'spiriting' i.e. kidnapping children for work in the Americas, had been sanctioned by the Privy Council since 1620, but the Custody of Children Act (the 'Barnardo’s Act) legalised the work of private emigration societies for removing poor children from workhouses, industrial schools, reformatories and private care facilities, to British colonies. | >- | 1899 | UK Government | The Elementary Education (Defective and Epileptic Children) Act allowed school authorities to make arrangements for ascertaining which children, by reason of mental or physical defect, were incapable of receiving proper benefit from instruction in the ordinary schools. |

20th century

| Timeline of 20th century events related to Children's Rights in the UK in chronological order | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Parties | Event | Image | |

| 1904 | UK Government | The Prevention of Cruelty to Children Act gave the NSPCC a statutory right to intervene in child protection cases. | ||

| 1905 | UK Government | A specialist juvenile offenders court was tried in Birmingham, and formally established in the Children Act 1908 Children Act 1908 The 1908 Children's Act, also known as Children and Young Persons Act, part of the Children's Charter was a piece of government legislation passed by the Liberal government, as part of the British Liberal Party's liberal reforms package... , along with juvenile courts. Borstals, a kind of youth prison, were established under the Prevention of Crime Act, with the aim of separating youths from adult prisoners. |

||

| 1910 | Home Office | Allegations in John Bull John Bull (magazine) John Bull Magazine was a weekly periodical established in the City, London EC4, by Theodore Hook in 1820.-Publication dates:It was a popular periodical that continued in production through 1824 and at least until 1957... of abuse at a boys' reformatory, the Akbar Nautical Training School, Heswall, included accusations that that boys were gagged before being birched, that boys who were ill were caned as malingerers, and that punishments included boys being drenched with cold water or being made to stand up all night for a trivial misdemeanour. It was further alleged that boys had died as a result of such punishments. The Home Office investigation rejected the allegations, but found that there had been instances of "irregular punishments". |

||

| 1915 | A. S. Neill A. S. Neill Alexander Sutherland Neill was a Scottish progressive educator, author and founder of Summerhill school, which remains open and continues to follow his educational philosophy to this day... |

In 1915 the teacher A.S.Neill wrote his first book in his Dominie series of semi-autobiographical novels, 'A Dominies Log'. This was the first of his writings to promote and advocate for children's rights in UK schools, especially the rights to play, to protection and to control their own learning. He went on to found what is now the oldest school based on children's rights, Summerhill (1921). The school and Neill's writings went on to influence schools and education systems around the world, including the UK | ||

| January 1916 | UK Government | In the early years of the 20th century the National Service League National Service League The National Service League was a British pressure group founded in February 1902 to alert the country to the inadequacy of the British Army to fight a major war and to propose the solution of national service.... had urged compulsory military training for all men aged between 18 and 30. After the outbreak of World War I some two million men enlisted voluntarily, some in Pals battalion Pals battalion The Pals battalions of World War I were specially constituted units of the British Army comprising men who had enlisted together in local recruiting drives, with the promise that they would be able to serve alongside their friends, neighbours and work colleagues , rather than being arbitrarily... s, but mostly in regular regiments and corps. Enthusiasm diminished as casualties increased, and the Military Service Act Military Service Act (United Kingdom) The Military Service Act 1916 was an Act passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom during the First World War. It was the first time that legislation had been passed in British military history introducing conscription... of January 1916 introduced conscription Conscription Conscription is the compulsory enlistment of people in some sort of national service, most often military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and continues in some countries to the present day under various names... . Boys from the age of 18 were liable to be called-up for service Men of Class 1 (that is, 18 year olds), once enrolled, were given the option of returning home or remaining with the Colours and undergoing special training until they were 19. At the start of 1914 the British Army had a reported strength of 710,000 men including reserves. By the end of the war almost 1 in 4 of the total male population of the UK had joined, over five million men, and almost half the infantry were 19 or younger Recruitment to the British Army during World War I At the start of 1914 the British Army had a reported strength of 710,000 men including reserves, of which around 80,000 were regular troops ready for war. By the end of World War I almost 1 in 4 of the total male population of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland had joined, over five... . Conscription ceased with the termination of hostilities on 11 November 1918 and all conscripts were discharged, if they had not already been so, on 31 March 1920. |

||

| 1918 | Maternity and Child Welfare Act | The War prompted the government to direct funds towards infant welfare centres, and the Act encouraged local authorities to continue this work by introducing the principle of free ante-natal care and free medical care of under-fives. Most of the work was undertaken by volunteers, who were able to claim support for the resources they used. These measures taken together contributed to an astonishing decline in infant mortality in the first three decades of the 20th century. | ||

| 1919 | Save the Children Fund | In the aftermath of the Great War social reformer Eglantyne Jebb Eglantyne Jebb Eglantyne Jebb was a British social reformer.- Early life :She was born in 1876 in Ellesmere, Shropshire, and grew up on her family's estate. The Jebbs were a well-off family and had a strong social conscience and commitment to public service... and her sister Dorothy, who married Labour MP C.R. Buxton, documented the terrible misery in which the children of Central, Eastern and Southern Europe were plunged, and believing there was no such thing as an "enemy" child, founded the Save the children Fund in London to address their needs. The Save the Children International Union International Save the Children Union The International Save the Children Union was a Geneva-based international organisation of children's welfare organisations founded in 1920 by Eglantyne Jebb and her sister Dorothy Buxton, who had earlier founded Save the Children in the UK... (SCIU) was founded in Geneva Geneva Geneva In the national languages of Switzerland the city is known as Genf , Ginevra and Genevra is the second-most-populous city in Switzerland and is the most populous city of Romandie, the French-speaking part of Switzerland... in 1920 with Save the Children and Swedish Rädda Barnen Rädda Barnen Rädda Barnen is the name of the Swedish section of the International Save the Children Alliance.The Swedish section was founded on November 19, 1919 by Ellen Palmstierna together with writer Elin Wägner and Gerda Marcus .-See also:* Timeline of young people's rights in the United Kingdom... as leading members. Jebb went on to draft the Declaration of the Rights of the Child Declaration of the Rights of the Child The Declaration of the Rights of the Child is the name given to a series of related children's rights proclamations drafted by Save the Children founder Eglantyne Jebb in 1923.... in collaboration with Lady Blomfield Lady Blomfield Lady Sara Louisa Blomfield was a distinguished early member of the Bahá'í Faith in the British Isles, and a supporter of the rights of children and women.... . |

||

| 1921 | Summerhill School Summerhill School Summerhill School is an independent British boarding school that was founded in 1921 by Alexander Sutherland Neill with the belief that the school should be made to fit the child, rather than the other way around... |

As portrayed in his Dominie book, A Dominie Abroad (Herbert Jenkins, 1923), A.S.Neill founded what would become known as Summerhill School in Hellerau, a suburb of Dresden. It was part of an International school called the Neue Schule. Neill moved his school to Sonntagsberg in Austria. By 1923 Neill had moved to the town of Lyme Regis in the south of England, to a house called Summerhill where he began with 5 pupils. The school continued there until 1927, when it moved to the present site at Leiston in the county of Suffolk, taking the name of Summerhill with it. The Secretary of the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child wrote in support of the school when it faced closure from Government inspectors, that it 'surpasses all expectations' in its implementation of children's rights, particularly Article 12. Children's BBC made a four part drama called Summerhill based on its fight for survival against the government. |

||

| March 1921 | Family Planning Family planning Family planning is the planning of when to have children, and the use of birth control and other techniques to implement such plans. Other techniques commonly used include sexuality education, prevention and management of sexually transmitted infections, pre-conception counseling and... |

Marie Stopes Marie Stopes Marie Carmichael Stopes was a British author, palaeobotanist, campaigner for women's rights and pioneer in the field of birth control... opened the UK's first family planning clinic in London, the Mothers' Clinic, offering a free service to married women and gathering scientific data about contraception. The opening of the clinic created a major social impact on the 20th century, marking the start of a new era in fertility control by promising an opportunity for the modern world to break out of the Malthusian Trap Malthusian catastrophe A Malthusian catastrophe was originally foreseen to be a forced return to subsistence-level conditions once population growth had outpaced agricultural production... . An admirer of Hitler's Nazism and a Eugenicist, Stopes' brand of Feminism Feminism Feminism is a collection of movements aimed at defining, establishing, and defending equal political, economic, and social rights and equal opportunities for women. Its concepts overlap with those of women's rights... sought selective breeding to achieve racial purity, sterilisation of those 'unfit for parenthood' and consigned the Rights of Children to the backwaters of the Pro/Anti Abortion debate. |

||

| 1932 | Children and Young Persons (Scotland) Act | The Act provided for young offender Young offender A young offender is a young person who has been convicted or cautioned for a criminal offence. Criminal justice systems often deal with young offenders differently from adult offenders, but different countries apply the term 'young offender' to different age groups depending on the age of criminal... s, to be sent to an Approved School Approved School Approved School is a term formerly used in the United Kingdom to mean a particular kind of residential institution to which young people could be sent by a court, usually for committing offences but sometimes because they were deemed to be beyond parental control... , put on probation, or put into the care of a "fit person". Courts could, in addition, sentence male juvenile offenders to be whipped with not more than six strokes of a birch rod by a constable". |

||

| 1932/33 | UK Government | The Children and Young Persons Act 1932 broadened the powers of juvenile courts and introduced supervision orders for children at risk. The Children and Young Persons Act 1933 Children and Young Persons Act 1933 The Children and Young Persons Act 1933 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland... provided for young offender Young offender A young offender is a young person who has been convicted or cautioned for a criminal offence. Criminal justice systems often deal with young offenders differently from adult offenders, but different countries apply the term 'young offender' to different age groups depending on the age of criminal... s, to be sent to an Approved School Approved School Approved School is a term formerly used in the United Kingdom to mean a particular kind of residential institution to which young people could be sent by a court, usually for committing offences but sometimes because they were deemed to be beyond parental control... , put on probation, or put into the care of a "fit person". Courts could, in addition, sentence male juvenile offenders to be whipped with not more than six strokes of a birch rod by a constable". The Act also introduced Remand Homes for youths temporarily held in custody, to await a court hearing. The Home Office maintained a team of inspectors who visited each institution from time to time. Offenders, as well as receiving academic tuition, were assigned to work groups for such activities as building and bricklaying, metalwork, carpentry and gardening. Many approved schools were known for strict discipline, and were essentially "open" institutions from which it was relatively easy to abscond. This allowed the authorities to claim that they were not "Reformatories", and set them apart from Borstal. The age of criminal responsibility Defense of infancy The defense of infancy is a form of defense known as an excuse so that defendants falling within the definition of an "infant" are excluded from criminal liability for their actions, if at the relevant time, they had not reached an age of criminal responsibility... was raised from 7 to 8, and no-one could be hanged for an offence committed under the age of 18. The Act consolidated most existing child protection legislation, enforcing strict punishments for anyone over 16 found to have neglected a child. Guidelines on the employment of school-age children were set, with a minimum age of 14 for full-time employment. |

||

| November 1938 | Kindertransport Kindertransport Kindertransport is the name given to the rescue mission that took place nine months prior to the outbreak of the Second World War. The United Kingdom took in nearly 10,000 predominantly Jewish children from Nazi Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Poland and the Free City of Danzig... |

A few days after Kristallnacht Kristallnacht Kristallnacht, also referred to as the Night of Broken Glass, and also Reichskristallnacht, Pogromnacht, and Novemberpogrome, was a pogrom or series of attacks against Jews throughout Nazi Germany and parts of Austria on 9–10 November 1938.Jewish homes were ransacked, as were shops, towns and... in Nazi Germany, a delegation of British Jewish leaders appealed in person to the Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, on the eve of a major Commons debate on refugees. They requested that the British government permit the temporary admission of Jewish children and teenagers who would later re-emigrate, among other measures. The Jewish community promised to pay guarantees for the refugee children. The Cabinet decided that the nation would accept unaccompanied children ranging from infants up to teenagers under the age of 17. |

||

| April 1939 | UK Government | The Military Training Act Conscription in the United Kingdom Conscription in the United Kingdom has existed for two periods in modern times. The first was from 1916 to 1919, the second was from 1939 to 1960, with the last conscripted soldiers leaving the service in 1963... sought to 'call up' boys from age 18 as 'militiamen', to distinguish them from the regular army. The intention was for conscripts to undergo six months basic training before being discharged into an active reserve, for subsequent recall to short training periods and an annual camp. Superseded by the National Service (Armed Forces) Act 1939 National Service (Armed Forces) Act 1939 The National Service Act 1939 was enacted immediately by the Parliament of the United Kingdom on the day the United Kingdom declared war on Germany on 3 September 1939, at the start of the Second World War. It superseded the Military Training Act 1939 passed in May that year, and enforced full... enacted immediately by Parliament on 3 September 1939 - the date of declaration of war on Germany. Liability to full-time conscription was enforced on all males between 18 and 41. By 1942, all male British subjects resident in Great Britain aged 18–50 were liable to call-up, with only a few categories exempted, and female subjects aged 20–29. |

||

| 1944 | UK Government | In 1939 the government had considered raising school leaving age to 15, but this was delayed by the onset of World War Two. The Education Act Education Act 1944 The Education Act 1944 changed the education system for secondary schools in England and Wales. This Act, commonly named after the Conservative politician R.A... succeeded in extending compulsory education to age 15, which took effect from 1947. |

||

| 1945 | UNESCO UNESCO The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations... |

Following dissolution of the League of Nations, the United Nations was founded on 24 October, but had already in 1943 begun operating UNRRA, a relief organization to combat famine and disease in liberated Europe. UNESCO UNESCO The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations... was also established with Julian Huxley Julian Huxley Sir Julian Sorell Huxley FRS was an English evolutionary biologist, humanist and internationalist. He was a proponent of natural selection, and a leading figure in the mid-twentieth century evolutionary synthesis... as the first Director General, standing at the centre of the post-World War II revival of education. Huxley was a prominent member of the British Eugenics Society, and one of the liberal intellectual elite of the time who believed in birth control and 'voluntary' sterilization for the "virtual elimination of the few lowest and most degenerate types". Huxley's six-year term of office, defined in the Charter, was reduced to two years, and UNESCO's education program became a collaboration with the International Bureau of Education International Bureau of Education The International Bureau of Education is a UNESCO center specializing in education, whose goal is to facilitate the provision of quality education throughout the world.-History:... , of which Jean Piaget Jean Piaget Jean Piaget was a French-speaking Swiss developmental psychologist and philosopher known for his epistemological studies with children. His theory of cognitive development and epistemological view are together called "genetic epistemology".... was Director from 1929 until 1968. Piaget had declared during the second world war in 1940: "The common wealth of all civilizations is the education of the child." |

|

|

| 11 December 1946 | United Nations General Assembly United Nations General Assembly For two articles dealing with membership in the General Assembly, see:* General Assembly members* General Assembly observersThe United Nations General Assembly is one of the five principal organs of the United Nations and the only one in which all member nations have equal representation... |

The first major step on behalf of children taken by the United Nations, was UNICEF's creation in 1946 co-founded by Maurice Pate Maurice Pate Maurice Pate was an American humanitarian and businessman. With Herbert Hoover, Pate co-founded the United Nations Children's Fund in 1947 and served as its first executive director from 1947 until his death in 1965.Talking about the United Nations, Dag Hammarskjöld, its second Secretary-General,... and Ludwik Rajchman Ludwik Rajchman Ludwik J. Rajchman was a Polish bacteriologist. He was one of the founders of UNICEF.In 1929 and 1930-1931, he served as a medical adviser to Chiang Kai-shek and Song Ziwen. In 1931-1939, he was an expert of China's National Economic Council, which had been set up with the aid of the League of... to provide emergency food and healthcare to children in countries devastated by World War II. Two years later, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights Universal Declaration of Human Rights The Universal Declaration of Human Rights is a declaration adopted by the United Nations General Assembly . The Declaration arose directly from the experience of the Second World War and represents the first global expression of rights to which all human beings are inherently entitled... was adopted by the UN General Assembly. |

||

| 1947 | UK Government | After World War II the National Service Act 1947 and subsequent measures ordained peacetime conscription of all males aged 18 for a set period (originally 1 year, later two years) until National Service ceased in 1960, with final Demobilization Demobilization Demobilization is the process of standing down a nation's armed forces from combat-ready status. This may be as a result of victory in war, or because a crisis has been peacefully resolved and military force will not be necessary... in 1963. Post-1945 some 1,132,872 men were conscripted to serve the British Army on reaching the age of 18. About 125,000 served in an active theatre of operations, and were expected to fight guerrillas or cope with riots or civil war situations with minimal training in such combat situations as Korea, Malaya, Suez and Aden. |

||

| July 1948 | UK Government | The War landed more than a million children, evacuated from town centres, on to local councils with inadequate resources to care for them. Many were placed in foster homes and became emotionally disturbed, reacting by bed-wetting, stealing and running away. After the war, many children who had no families to return to, became 'nobody's children'. The Children Act 1948 Children Act 1948 The Children Act 1948 was an Act of Parliament in the United Kingdom that established a comprehensive childcare service. It reformed the services available to deprived children, consolidating existing childcare legislation and establishing departments “in which professional social work practice... finally brought together responsibility for children without adequate parents, formerly dealt with under the Poor Law Poor Law The English Poor Laws were a system of poor relief which existed in England and Wales that developed out of late-medieval and Tudor-era laws before being codified in 1587–98... , and responsibility for delinquent children in Remand Homes+, formerly under the aegis of Local Education Authorities, with the requirement for every County and County Borough to establish a Children's Committee and appoint a Children's Officer. This has been the basis on which social workers have acted on behalf of children ever since. Detention Centres, under the Prison Department of the Home Office, were later introduced for miscreants Summary offence A summary offence is a criminal act in some common law jurisdictions that can be proceeded with summarily, without the right to a jury trial and/or indictment .- United States :... , designed to administer Common law Common law is law developed by judges through decisions of courts and similar tribunals rather than through legislative statutes or executive branch action... a "short sharp shock" to older teenagers through drilling, physical jerks, military-style discipline, and cold showers before dawn. |

||

| 20 November 1959 | United Nations General Assembly United Nations General Assembly For two articles dealing with membership in the General Assembly, see:* General Assembly members* General Assembly observersThe United Nations General Assembly is one of the five principal organs of the United Nations and the only one in which all member nations have equal representation... |

The Declaration of the Rights of the Child Declaration of the Rights of the Child The Declaration of the Rights of the Child is the name given to a series of related children's rights proclamations drafted by Save the Children founder Eglantyne Jebb in 1923.... , covering children's rights, maternal protection, health, adequate food, shelter and education, was adopted by the General Assembly in 1959 as a milestone in the commitment of world governments to focus on the needs of children — an issue once considered peripheral to development, but serving as a moral, rather than legally binding framework. |

||

| 1967 | Court Lees Approved School Approved School Approved School is a term formerly used in the United Kingdom to mean a particular kind of residential institution to which young people could be sent by a court, usually for committing offences but sometimes because they were deemed to be beyond parental control... |

The Gibbens report into allegations of excessive punishment at the school prompted Home Secretary Roy Jenkins Roy Jenkins Roy Harris Jenkins, Baron Jenkins of Hillhead OM, PC was a British politician.The son of a Welsh coal miner who later became a union official and Labour MP, Roy Jenkins served with distinction in World War II. Elected to Parliament as a Labour member in 1948, he served in several major posts in... to announce its immediate closure, and the need to phase out corporal punishment in all Approved Schools. Under the Children and Young Persons Act 1969 responsibility for Approved Schools was devolved from the Home Office to local social services authorities, and they were renamed "Community Homes with Education". |

||

| 1968 | Scotland | Following publication of the Kilbrandon report Charles Shaw, Baron Kilbrandon Charles James Dalrymple Shaw, Baron Kilbrandon PC was a Scottish judge and law lord.-Family and education:... in 1964, the Social Work (Scotland) Act 1968 set up the Scottish Children’s Hearings system and revolutionised juvenile justice in Scotland by removing children in trouble from the criminal courts. The institutional framework for supporting children and families established on the basis of the key recommendations of the report has been largely unchanged since it was introduced in 1971. Changes from the latest review, currently under way in 2008, are planned for implementation from 2010. |

||

| 1970 | United Kingdom | Having concluded that the historical causes for fixing 21 years as the age of majority were no longer relevant to contemporary society, the Latey Committee's recommendation was accepted, that the Age of majority Age of majority The age of majority is the threshold of adulthood as it is conceptualized in law. It is the chronological moment when minors cease to legally be considered children and assume control over their persons, actions, and decisions, thereby terminating the legal control and legal responsibilities of... , including voting age Voting age A voting age is a minimum age established by law that a person must attain to be eligible to vote in a public election.The vast majority of countries in the world have established a voting age. Most governments consider that those of any age lower than the chosen threshold lack the necessary... , should be reduced to 18 years. |

||

| 1972 | UK Government | The Children Act 1972 set the minimum school leaving age at 16. After the 1972 Act schools were provided with temporary buildings to house their new final year, known as ROSLA Roßla Roßla or Rossla is a village and a former municipality in the Mansfeld-Südharz district, Saxony-Anhalt, Germany. Since 1 January 2010, it is part of the municipality Südharz. From 1706–1803, Roßla was the seat of Stolberg-Rossla.... (Raising School Leaving Age) buildings and were delivered to schools as self assembly packs. Although not designed for long-term use, many schools continued using them. |

||

| 1981 | 1981 Brixton riot | One of the most serious riots in the 20th century fuelled by racial and social discord, brought black and white youth into violent confrontation with thousands of police. Further riots ensued that year throughout Britain. The Scarman Report detailed a loss of confidence and mistrust in the police and their methods of policing after liaison arrangements between police, community and local authority had collapsed. Recommendations for policing reforms were introduced in 1984. However, the 1999 MacPherson Inquiry into teenager Stephen Lawrence Stephen Lawrence Stephen Lawrence was a black British teenager from Eltham, southeast London, who was stabbed to death while waiting for a bus on the evening of 22 April 1993.... 's murder, found that Scarman's recommendations had been ignored, and concluded that the Metropolitan Police Service Metropolitan Police Service The Metropolitan Police Service is the territorial police force responsible for Greater London, excluding the "square mile" of the City of London which is the responsibility of the City of London Police... was institutionally racist Institutional racism Institutional racism describes any kind of system of inequality based on race. It can occur in institutions such as public government bodies, private business corporations , and universities . The term was coined by Black Power activist Stokely Carmichael in the late 1960s... . |

||

| 1984 | UK Government | Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 The Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 is an Act of Parliament which instituted a legislative framework for the powers of police officers in England and Wales to combat crime, as well as providing codes of practice for the exercise of those powers. Part VI of PACE required the Home Secretary... Part IV 37(15). A child is defined as under 17 years old. The Act provides for an Appropriate adult Appropriate adult Appropriate adult is a defined term in the United Kingdom legal system for a parent or guardian or social worker who must be present if a young person or vulnerable adult is to be searched or questioned in police custody... to be called to the police station whenever a child has been detained in police custody. |

||

| 1985 | The Children's Society The Children's Society The Children's Society, formally The Church of England Children's Society, is a UK charity allied to the Church of England and driven by a belief that all children deserve a good childhood.-History:... |

The first refuge is opened for runaways. After 20+ years of campaigning, the government in 2008 set out plans to improve work with the estimated 100,000 under-16s who run away from home or care each year. | ||

| 1985 | House of Lords House of Lords The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster.... |

Gillick competence Gillick competence Gillick competence is a term originating in England and is used in medical law to decide whether a child is able to consent to his or her own medical treatment, without the need for parental permission or knowledge.... ruling in the case Gillick v West Norfolk and Wisbech Area Health Authority, which sought to decide in medical law whether a child is able to consent to his or her own medical treatment, without the need for parental permission or knowledge. A child is defined as 16 years or younger. The ruling, which applies in England and Wales (but not in Scotland), is significant in that it is broader in scope than merely medical consent. It lays down that the authority of parents to make decisions for their minor children is not absolute, but diminishes with the child's evolving maturity; except in situations that are regulated otherwise by statute, the right to make a decision on any particular matter concerning the child shifts from the parent to the child when the child reaches sufficient maturity to be capable of making up his or her own mind on the matter requiring decision. |

||

| 1986 | Child Migrants Scandal | Social worker Margaret Humphreys Margaret Humphreys Margaret Humphreys CBE OAM is a social worker, author and whistleblower from Nottingham, England. In 1987, she investigated and brought to public attention the British government programme of Home Children... ' received a letter from a woman in Australia who had been sent on a boat from the UK to a children's home in Australia, age four, and wanted help in tracing her parents in Britain. Humphrey’s subsequent research exposed the abuses of private emigration societies operating under the 1891 Custody of Children Act - a key subtext of which was the aim of supplying Commonwealth countries with sufficient "white stock" particularly in relation to Australia. A Department of Health Report shows that at least 150,000 children aged between 3 and 14 were sent to Commonwealth countries, in a programme that did not end until 1967. The children – the majority of whom were already in some form of social or charitable care – were cut off from their families and even falsely informed that they were orphans. Most were sent with the promise of a better life – but the reality was often very different, with many facing abuse and a regime of unpaid labour. A number of organisations, including Fairbridge Kingsley Fairbridge Kingsley Ogilvie Fairbridge was the founder of a child emigration scheme to British colonies and the Fairbridge Schools... , Barnardo's Barnardo's Barnardo's is a British charity founded by Thomas John Barnardo in 1866, to care for vulnerable children and young people. As of 2010, it spends over £190 million each year on more than 400 local services aimed at helping these same groups... , the Salvation Army Salvation Army The Salvation Army is a Protestant Christian church known for its thrift stores and charity work. It is an international movement that currently works in over a hundred countries.... , the Children's Society and some Catholic groups, were involved in sending children abroad. |

||

| 1986 | Wales, Bryn Estyn Wales child abuse scandal The Wales child abuse scandal was the subject of a three-year, £13 million investigation into the sexual abuse of children in care homes in North Wales over two decades.... |

Although Care workers in Clwyd had been convicted of sex abuse as long ago as 1976, with allegations and investigations in Gwynedd in the 1980s, the scandal was only exposed after Alison Taylor, a children's home head in Gwynedd, pressed her concerns at the highest levels. During police investigations into Ms Taylor's concerns in 1986-87, the authorities constructed a "wall of disbelief" from the outset. An inquiry ordered by the Home Secretary in 1996 into quality of care and standards of education, found both to be below acceptable levels in all the homes investigated. | ||

| 1989 | United Nations General Assembly United Nations General Assembly For two articles dealing with membership in the General Assembly, see:* General Assembly members* General Assembly observersThe United Nations General Assembly is one of the five principal organs of the United Nations and the only one in which all member nations have equal representation... |

The UN Convention on Children's Rights Convention on the Rights of the Child The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child is a human rights treaty setting out the civil, political, economic, social, health and cultural rights of children... was adopted into international law. |

|

|

| 1989 | UK Government | The Children Act 1989 Children Act 1989 The Children Act 1989 is a British Act of Parliament that altered the law in regard to children. In particular, it introduced the notion of parental responsibility. Later laws amended certain parts of the Children Act... was intended as the main piece of legislation setting out the legal framework for child protection procedures e.g. enquiries and conferences and introduced the notion of parental responsibility Parental responsibility (access and custody) In the nations of the European Union and elsewhere, parental responsibility refers to the rights and privileges which underpin the relationship between a child and either of the child's parents or those adults who have a significant role in the child's life... . Provisions apply to all children under 18. It was very wide-ranging and covered all paid childcarers outside the parental home for under-8's, adoption and fostering, and many aspects of family law including divorce. Although the Act aimed to enshrine consistency with the UNCRC approach that 'the best interests of the child are pre-eminent', UN monitoring committee reports issued in 1995 and 2002 noted that the principle of primary consideration for the best interests of the child was not consistently reflected in legislation and policies affecting children. |

||

| 1990/1991 | The Pindown Pindown Pindown was a method of punishment used in children's homes in Staffordshire, England in the 1980s. It involved locking children in rooms called "pindown rooms", sometimes for periods of weeks or months, similar to a lockdown in prisons... Enquiry |

Allan Levy QC inquired into a method of discipline used in Staffordshire children's homes in the 1980s. Pindown was named after the notion that it would "pin down the problem" relating to a particular "difficult" child, and involved locking children in "pindown rooms", sometimes for periods of weeks or months. The 2000 Kilgallon report into Northumberland housing for children with special needs revealed that Pindown tactics were employed between 1972 and 1984. | ||

| 12 July 1990 | Phillip Knight | The 17-year-old died in custody at HM Prison Swansea Swansea (HM Prison) HM Prison Swansea is a Category B/C men's prison, located in the Sandfields area of Swansea, Wales. The prison is operated by Her Majesty's Prison Service, and is colloquially known as 'Cox's farm', after a former governor.-History:... as a result of self-inflicted injuries. An inquest yielded an open verdict. Knight was the first of 30 children to die in custody since 1990. The inquest into 16 year old Joseph Scholes' death in custody in March 2002, led the coroner to support the call for a public inquiry. |

||

| 1991 | United Kingdom | UK ratification of United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, with a number of reservations. UNCRC defines a child as under 18 years old, unless an earlier age of majority is recognized by a country's law. | ||

| February 1993 | James Bulger Murder of James Bulger James Patrick Bulger was a boy from Kirkby, England, who was murdered on 12 February 1993, when aged two. He was abducted, tortured and murdered by two ten-year-old boys, Robert Thompson and Jon Venables .Bulger disappeared from the New Strand Shopping Centre in Bootle, near Liverpool, while... |

The murder of two-year old James Bulger Murder of James Bulger James Patrick Bulger was a boy from Kirkby, England, who was murdered on 12 February 1993, when aged two. He was abducted, tortured and murdered by two ten-year-old boys, Robert Thompson and Jon Venables .Bulger disappeared from the New Strand Shopping Centre in Bootle, near Liverpool, while... , by Jon Venables and Robert Thompson, both aged 10, prompted national debate about the relationship between Childhood Childhood Childhood is the age span ranging from birth to adolescence. In developmental psychology, childhood is divided up into the developmental stages of toddlerhood , early childhood , middle childhood , and adolescence .- Age ranges of childhood :The term childhood is non-specific and can imply a... and criminality, which led to abolition in 1998 of the distinction with regard to criminal responsibility Defense of infancy The defense of infancy is a form of defense known as an excuse so that defendants falling within the definition of an "infant" are excluded from criminal liability for their actions, if at the relevant time, they had not reached an age of criminal responsibility... between young persons aged at least 14 and children aged between 10 and 14. |

||

| June 1994 | Fred West Fred West Frederick Walter Stephen West , was a British serial killer. Between 1967 and 1987, he alone, and later, he and his wife Rosemary, tortured, raped and murdered at least 11 young women and girls, many at the couple's homes. The majority of the murders occurred between May 1973 and September 1979 at... |

After their children alerted authorities to the West's rape of their daughter, investigations revealed that between 1967 and 1987, Fred and his wife Rosemary tortured, raped and murdered at least 12 girls and young women, whose disappearance had previously gone unnoticed. The case highlighted the inadequacies of the National Missing Persons Bureau and eventually gave rise to the National Policing Improvement Agency National Policing Improvement Agency The United Kingdom's National Policing Improvement Agency is a non-departmental public body established to support police by providing expertise in such areas as information technology, information sharing, and recruitment.-Background:... established in 2007. |

||

| February 1995 | United Nations United Nations The United Nations is an international organization whose stated aims are facilitating cooperation in international law, international security, economic development, social progress, human rights, and achievement of world peace... |

The committee responsible for monitoring implementation of UNCRC issued first concluding observations on the UK's progress. | ||