W. H. R. Rivers

Encyclopedia

William Halse Rivers Rivers, FRCP, FRS, (12 March 1864 - ) was an English

anthropologist, neurologist

, ethnologist and psychiatrist

, best known for his work with shell-shocked

soldiers during World War I

. Rivers' most famous patient was the poet Siegfried Sassoon

. He is also famous for his participation in the Torres Straits expedition of 1898, and his consequent seminal work on the subject of kinship

.

Records from the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries show the Rivers family to be solidly middle-class with many Cambridge

, Church of England

and Royal Navy

associations, the most famous of which were Midshipman

William Rivers and his father Gunner

Rivers who both served aboard HMS Victory

.

.jpg) The senior Rivers, also called William, was the master gunner aboard The Victory and it is thanks to his commonplace book (now kept in the Royal Naval Museum library in Portsmouth) that many of the thoughts of the sailors aboard Nelson’s flagship are preserved. Midshipman Rivers, claimed to be ‘the man who shot the man who fatally wounded Lord Nelson’ proved himself to be a model of heroism in the Battle of Trafalgar

The senior Rivers, also called William, was the master gunner aboard The Victory and it is thanks to his commonplace book (now kept in the Royal Naval Museum library in Portsmouth) that many of the thoughts of the sailors aboard Nelson’s flagship are preserved. Midshipman Rivers, claimed to be ‘the man who shot the man who fatally wounded Lord Nelson’ proved himself to be a model of heroism in the Battle of Trafalgar

. In the course of his duties, the seventeen-year-old midshipman’s foot was almost completely blown off by a grenade, left attached to him ‘by a Piece of Skin abought 4 inch above the ankle’. Rivers asked first for his shoes, then told the gunner’s mate to look after the guns and informed Captain Hardy that he was going down to the cockpit. The leg was then sawn off, without anaesthetic, four inches below the knee. According to legend, he did not cry out once during the amputation nor during the consequent sealing of the wound with hot tar. When Gunner Rivers, anxious about his son’s welfare, went to the cockpit to ask after him the young man called out from the other side of the deck, ‘Here I am, Father, nothing is the matter with me; only lost my leg and that in a good cause.’ After the Battle, the senior Rivers wrote a poem about his remarkable son entitled ‘Lines on a Young Gentleman that lost his leg onboard the Victory in the Glorious action at Trafalgar’:

Born to another naval Rivers, Lt. William Rivers, R.N., then stationed at Deptford

, Henry Rivers followed many family traditions in being educated at Trinity College, Cambridge

and entering the church. Having earned his Bachelor of Arts in 1857, he was ordained as a Church of England priest in 1858, a career that would span almost 50 years until, in 1904, he was forced to tender his resignation due to ‘infirmities of sight and memory’.

In 1863, having obtained a curacy at Chatham in addition to a chaplain’s post, Henry Rivers was in a position to marry Elizabeth Hunt who was living with her brother James in Hastings

In 1863, having obtained a curacy at Chatham in addition to a chaplain’s post, Henry Rivers was in a position to marry Elizabeth Hunt who was living with her brother James in Hastings

, not far from Chatham.

The Hunts, like the Riverses, were an established naval and Church of England family. One of those destined for the pulpit was Thomas (1802–1851), but some quirk of originality set him off into an unusual career. While an undergraduate at Cambridge, Thomas Hunt had a friend who stammered badly and his efforts to aid the afflicted student led him to leave the University without taking a degree in order to make a thorough study of speech and its defects. He built up a good practise as a speech therapist and was patronised by Sir John Forbes MD FRS

, who sent him pupils for twenty four years. Hunt’s most famous case came about in 1842 when George Pearson, the chief witness in the case respecting the attempt on the life of Queen Victoria made by John Francis, was brought into court he was incapable of giving his evidence. However, after just a fortnight's instruction from Hunt he spoke easily, a fact certified by the sitting magistrate. Hunt died in 1851, survived by his wife Mary and their two children. His practise was then passed on to his son, James.

James Hunt (1833–1869) was an exuberant character, giving to each of his ventures his boundless energy and self-confidence. Taking up his father’s legacy with great zeal, by the age of 21 Hunt had published his compendious work, "Stammering and Stuttering, Their Nature and Treatment". This went into six editions during his lifetime and was reprinted again in 1870, just after his death, and for an eighth time in 1967 as a landmark in the history of speech therapy. In the introduction to the 1967 edition of the book, Elliot Schaffer notes that in his short lifetime James Hunt is said to have treated over 1,700 cases of speech impediment, firstly in his father’s practise and later at his own institute, Ore House near Hastings, which he set up with the aid a doctorate he had purchased in 1856 from the University of Giessen

in Germany.

In later, expanded editions, "Stammering and Stuttering" begins to reflect Hunt’s growing passion for anthropology exploring, as it does, the nature of language usage and speech disorders in non-European peoples. In 1856, Hunt had joined the Ethnological Society of London

and by 1859 he was its joint secretary. He was not, however, a popular man within the society as many of the members disliked his attacks on religious and humanitarian agencies represented by missionaries and the anti-slavery movement.

As a result of the antagonism, Hunt founded the Anthropological Society

and became its president, a position that would be taken up by his nephew almost sixty years later. It was mainly to do with Hunt’s efforts that the British Association for the Advancement of Science

(BAAS) accepted anthropology in 1866.

Even by Victorian standards, Hunt was a decided racist. His paper "On a Negro’s Place in Nature", delivered before the BAAS in 1863, was met with hisses and catcalls. What Hunt saw as “a statement of the simple facts” was in fact a defence of the subjection and slavery of African-Americans and a support of the belief in the plurality of human species.

In addition to his extremist views, Hunt also led his society to incur heavy debts. The controversies surrounding his conduct told on his health and, on the 29th of August 1869, Hunt died of ‘inflammation of the brain’ leaving a widow, Henrietta Maria, and five children.

Hunt’s speech therapy practise was passed onto Hunt’s brother-in-law, Henry Rivers, who had been working with him for some time. With the practise came many of Hunt’s established patients, most notably The Reverend Charles L. Dodgson (better known as Lewis Carroll

) who had been a regular visitor to Ore House.

To his nephew William, Hunt had left his books though a young Rivers had refused them, thinking that they would be of no use to him.

William, known as 'Willie' throughout his childhood, appears to have taken his Christian name from his famous uncle of Victory fame, as well as from a longstanding family tradition whereby the eldest son of every line would be baptised by that name. The origin of ‘Halse’ is unclear, though it is possible that there is some naval connection as it has been suggested that it could have been the name of someone serving alongside his uncle. Slobodin states that it is probable that the second 'Rivers' entered his name as a result of a clerical error on the baptismal certificate but since the register is filled in by his father’s hand and he was to perform the ceremony, one would think it unlikely that a mistake would have been made in this case. Slobodin is correct to note that there is a mistake on the registry of his birth but since his name was changed from the mistaken ‘William False Rivers Rivers’ to its later form, it seems probable that ‘Rivers’ was intended to appear as a given name as well as a surname.

William, known as 'Willie' throughout his childhood, appears to have taken his Christian name from his famous uncle of Victory fame, as well as from a longstanding family tradition whereby the eldest son of every line would be baptised by that name. The origin of ‘Halse’ is unclear, though it is possible that there is some naval connection as it has been suggested that it could have been the name of someone serving alongside his uncle. Slobodin states that it is probable that the second 'Rivers' entered his name as a result of a clerical error on the baptismal certificate but since the register is filled in by his father’s hand and he was to perform the ceremony, one would think it unlikely that a mistake would have been made in this case. Slobodin is correct to note that there is a mistake on the registry of his birth but since his name was changed from the mistaken ‘William False Rivers Rivers’ to its later form, it seems probable that ‘Rivers’ was intended to appear as a given name as well as a surname.

Rivers suffered from a stammer that never truly left him, he also had no sensory memory

although he was able to visualise to an extent if dreaming, in a half-waking, half-sleeping state or when feverish. This had not always been the case; Rivers notes that in his early life- specifically before the age of five- his visual imagery was far more definite than it became in later life and perhaps as good as that of the average child.

At first, Rivers had concluded that his loss of visual imagery had come about as a result of his lack of attention and interest in it. However, as he later came to realise, while images from his later life frequently faded into obscurity, those from his infancy still remained vivid.

As Rivers notes in Instinct and the Unconscious, one manifestation of his lack of visual memory was his inability to visualise any part of the upper floor of the house he lived in until he was five. This visual blank is made even more significant by the fact that Rivers was able to describe the lower floors of that particular house with far more accuracy than he had been able to with any house since and, although images of later houses were faded and incomplete, no memory since had been as inaccessible as that of the upper floor of his early home. With the evidence that he was presented with, Rivers was led to the conclusion that something had happened to him on the upper floor of that house, the memory of which was entirely suppressed because it ‘interfered with [his] comfort and happiness’. Indeed, not only was that specific memory rendered inaccessible but his sensory memory in general appears to have been severely handicapped from that moment.

If Rivers ever did come to access the veiled memory then he does not appear to make a note of it so the nature of the experience is open to conjecture. One such supposition was put forward by Pat Barker, in the second novel in her Regeneration Trilogy, The Eye in the Door

. Whatever the case, in the words of Barker's character Billy Prior, Rivers’ experience was traumatic enough to cause him to "put his mind's eye out".

Whatever his disadvantages, Rivers was an unquestionably able child. Educated first at a Brighton preparatory school and then, from the age of thirteen, as a dayboy at the prestigious Tonbridge School

, his academic abilities were noted from an early age. Young Rivers’ talents led to him being placed a year above others of his age at school and even within this older group he was seen to excel, winning prizes for Classics

and all around attainment. It is also worth noting that Rivers’ younger brother Charles was also a high achiever at the school; he too was awarded with the ‘Good Work’ prize and would go on to become a civil engineer

until, after a bad bout of malaria

contracted whilst in the Torres Straits with his brother, he was prompted by the elder Rivers to take up outdoor work.

The teenage Rivers, whilst obviously scholarly, was also involved in other aspects of school life. As the programme for the Tonbridge School sports day notes, on the 12th March 1880- Rivers’ sixteenth birthday- he ran in the mile race. The year before this he had been elected as a member of the school debating society, no mean feat for a boy who at this time suffered from a speech impediment which was almost paralytic.

Rivers was set to follow family tradition and take his University of Cambridge

Rivers was set to follow family tradition and take his University of Cambridge

entrance exam, possibly with the aim of studying Classics. Unfortunately, his plans were thwarted when, at the age of sixteen, he was struck down by typhoid fever

and forced to miss his final year of school. Without the scholarship, his family could not afford to send him to Cambridge but with typical resilience, Rivers did not dwell on the disappointment.

His illness had been a bad one, entailing long convalescence and leaving him with effects which at times severely handicapped him. As L. E. Shore notes: “he was not a strong man, and was often obliged to take a few days rest in bed and subsist on a milk diet”. The severity of the sickness and the shattering of dreams might have broken lesser men but for Rivers in many ways the illness was the making of him. Whilst recovering from the fever, Rivers had formed a friendship with one of his father’s speech therapy students, a young Army surgeon. His plan was formed: he would study medicine and apply for training in the Army Medical Department, later to become the Royal Army Medical Corps

.

Fuelled by this new resolve, Rivers studied medicine at the University of London

, where he matriculated in 1882, and St Bartholomew's Hospital

in London

. He graduated aged just 22, the youngest person to do so until recent times.

His sister Katharine wrote that when he came to visit the family he would often sleep for the first day or two. Astonishingly, considering the work that Rivers did in his relatively short lifetime, Seligman wrote in 1922 that "for many years he seldom worked for more than four hours a day". As Rivers' biographer Richard Slobodin points out, “among persons of extraordinary achievement, only Descartes seems to have put in as short a working day”.

As ever, Rivers did not allow his drawbacks to dishearten him", and instead of entering the army his love of travelling lead him to serve several terms as a ship's surgeon, travelling to Japan and North America in 1887. This was the first of many voyages; for, besides his great expeditions for work in the Torres Straits, Melanesia

, Egypt

, India

and the Solomon Islands

, he took holiday voyages twice to the West Indies, three times to the Canary Islands

and Madeira

, to America, to Norway

, to Lisbon

, as well as numerous visits to France

, Germany

, Italy

, Switzerland

and to visit family in Australia

.

Such voyages helped to improve his health, and possibly to prolong his life. He also took a great deal of pleasures from his experiences aboard ship, particularly when he had the honour of spending a month in the company of George Bernard Shaw

; he later described how he spent “many hours every day talking - the greatest treat of my life”.

. Soon after, he became house surgeon at the Chichester Infirmary (1887–9) and, although he enjoyed the town and the company of his colleagues, an appointment at Bart’s and the opportunity to return to the company of productive researchers in medicine proved too much to resist. He became house physician

at St Bartholomew's in 1889 and remained there until 1890.

At Bart’s, Rivers had been a physician to Dr. Samuel Gee

. Those under Gee were conscious of his indifference towards, if not actual dislike of, the psychological aspects of medicine. As Walter Langdon-Brown

surmises, it may have been a reaction against this which led Rivers and his fellow Charles S. Myers to devote themselves to these aspects.

Whatever his motivation, the fact that Rivers’s interests lay in neurology and psychology became evident in this period. Reports and papers given by Rivers at the Abernethian Society of St. Bart’s indicate a growing specialism in these fields: Delirium and its allied conditions (1889), Hysteria (1891) and Neurasthenia (1893).

Following the direction of his passion for the workings of the mind as it correlates with the workings of the body, in 1891 Rivers became house physician at the National Hospital for the Paralysed and Epileptic. It was here that he and Henry Head

were to meet and form a lasting friendship.

Rivers’s interest in the physiology of the nervous system and in ‘the mind’ that is, in sensory phenomena and mental states, was further stimulated by work in 1891, when he was chosen to be one of Victor Horsley’s

assistants at in the series of investigations which elucidated the existence and nature of electrical currents in the mammalian brain which took place at University College, London. That he was seconded to Horsley for the work is an indication of his growing reputation as a researcher.

In the same year, Rivers joined the Neurological Society of London

In the same year, Rivers joined the Neurological Society of London

and presented A Case of Treadler’s Cramp to a meeting of the society. The case serves today as a poignant reminder of the cost, to millions of lives, of Britain’s industrial supremacy.

Resigning from the National Hospital in 1892, Rivers travelled to Jena

to expand his knowledge of experimental psychology. Whilst in Jena, Rivers became fluent in German and attended lectures, not only on psychology but on philosophy as well. He also became deeply immersed in the culture; in a diary he kept of the journey he comments on the buildings, the picture galleries, the church services, and the education system, showing his wide interests and critical judgement. In this diary he also wrote that: “I have during the last three weeks come to the conclusion that I should go in for insanity when I return to England and work as much as possible at psychology.”

And ‘go in for insanity’ he did, becoming a Clinical Assistant at the Bethlem Royal Hospital

upon his return to England. In 1893, at the request of G.H Savage, he began assisting with lectures in mental diseases at Guy's Hospital

, laying special stress on their psychological aspect. At about the same time, due to the bidding of Professor Sully, he began to lecture on experimental psychology at University College, London.

When, in 1893, the unexpected invitation came to lecture in Cambridge on the functions of the sense organs, he was already deeply read in the subject. He had been captivated by Head’s accounts of the works of Ewald Hering

and had absorbed his views on colour vision and the nature of vital processes in living matter with avidity. However, with typical thoroughness he prepared himself for his new duties by spending the summer working in Heidelberg

with Emil Kraepelin

on measuring the effects of fatigue.

While it may have come as a surprise to Rivers, the offer of a Cambridge lectureship had come about as part of a long process of evolution within the University’s Natural Science

Tripos

. Earlier in 1893, Professor McKendrick, of Glasgow

, had examined subject and reported unfavourably on the scant knowledge of the special senses displayed by the candidates; it was in reaction to this that Sir Michael Foster

, who had seen the potential in this shy, retiring Bart’s man, appointed Rivers as a lecturer and he became Fellow Commoner at St John's College

forthwith. He was to become a Fellow

of the College in 1902.

At first, the appointment proved to be an arduous and exhausting one for Rivers who, at this point, still had ongoing teaching commitments at Guy’s hospital and at University College. In addition to these mounting responsibilities, in1897 he was put in temporary charge of the new psychological laboratory at University College. This was the same year in which Foster assigned him a room in the Physiology Department at Cambridge for use in psychological research. As a result, Rivers is listed in the histories of experimental psychology as simultaneously the director of the first two psychological laboratories in Britain.

In retrospect, it is easy to see the monumental nature of Foster’s appointment in lieu of the profound effects Rivers’s work would have on Cambridge and indeed in the scientific world in general. However, at the time the Cambridge University Senate were wary of his appointment. As Bartlett

writes: “how many times have I heard Rivers, spectacles waving in the air, his face lit by his transforming smile, tell how, in Senatorial discussion, an ancient orator described him as a "Ridiculous Superfluity"!”

The opposition of the Senate, while it was more vocal than serious, was distinctly detrimental to Rivers’s efforts since any assistance to his work was very sparingly granted. It wasn’t until 1901, eight years after his appointment, that he was allowed the use of a small cottage for the ‘laboratory’, and given thirty-five pounds annually (later, and somewhat begrudgingly, increased to fifty) for purchase and upkeep of equipment. For several years Rivers continued thus, and then, stimulated by him and others, the Moral Science Board stretched out a rather timid and tentative hand again and, in 1903, Rivers and his assistants and students moved to another small building in St Tibbs Row. These working spaces were characterised as being ‘dismal’, ‘damp, dark and ill-ventilated’ but these poor working conditions did not seem to dishearten the Cambridge psychologists. Indeed, the effect was quite the contrary, psychology began to thrive: “perhaps, in the early days of scientific progress, a subject often grows all the more surely if its workers have to meet difficulties, improvise their apparatus, and rub very close shoulders one with another.” It was not until 1912 that a well-equipped laboratory was built under the directorship of Charles S. Myers, one of Rivers’s earliest and ablest pupils, who was wealthy and able to supplement the University grant with his own funds.

At this point the preoccupations of the Cambridge psychologists and of Rivers were with the special senses: colour vision, optical illusions, sound-reactions and perceptual processes. In these fields, Rivers was rapidly becoming eminent. He was invited to write a chapter on vision for Schäfer's Handbook of Physiology and this contribution, according to Bartlett, “still remains, from a psychological point of view, one of the best in the English Language”. In it he set out in a masterly way the work of previous investigators, modestly incorporating his own, and critically examining the rival theories of colour vision, pointing out clearly the importance of psychological factors in, for instance, the phenomena of contrast.

At this point the preoccupations of the Cambridge psychologists and of Rivers were with the special senses: colour vision, optical illusions, sound-reactions and perceptual processes. In these fields, Rivers was rapidly becoming eminent. He was invited to write a chapter on vision for Schäfer's Handbook of Physiology and this contribution, according to Bartlett, “still remains, from a psychological point of view, one of the best in the English Language”. In it he set out in a masterly way the work of previous investigators, modestly incorporating his own, and critically examining the rival theories of colour vision, pointing out clearly the importance of psychological factors in, for instance, the phenomena of contrast.

For his own experiments on vision, Rivers worked with two of his graduate medical students, Charles S. Myers and William McDougall

who assisted him at this period in a series of experiments on vision and with whom he formed close friendships. Rivers also collaborated with the pioneer instrument maker Sir Horace Darwin in the improvement of apparatus for recording sensations, especially those involved in vision. This collaboration was the basis of a lifelong friendship between Rivers and the genial son of Charles Darwin

.

Another important work of this period was an investigation of the influence of tea, coffee, alcohol, tobacco, and a number of other drugs on the capacity for doing work both muscular and mental. For this research he was well fitted after his work under Kraepelin at Heidelberg. A great many of these experiments Rivers made on himself, and for this purpose gave up for a period of two years not only alcoholic beverages and tobacco, which was easy enough for him as he liked neither, but all tea, coffee and cocoa as well. Although the investigation was initially formed with physiological motives in mind, it soon became clear that a strong psychological influence was also involved in the act of taking the substances. Rivers realised that part of the effects- mental and physical- that substances had were caused psychologically by the excitement of knowing that one is indulging. In order, therefore, to eliminate “all possible effects of suggestion, sensory stimulation and interest”, Rivers made sure that the substances were disguised from him so that he was not aware, on any given occasion, whether he was taking a drug or a control substance. This was the first experiment of its kind to use this ‘double-blind’ procedure and, in recognition of this momentous study, Rivers was appointed Croonian Lecture

r to the Royal College of Physicians in 1906.

In December 1897 Rivers’s achievements were recognised by the University of Cambridge who honoured him with the degree of M.A. honoris causa

and, in 1904 with the assistance of Professor James Ward

, Rivers made a further mark on the world of psychological sciences, founding and subsequently editing the British Journal of Psychology.

Despite his many successes, Rivers was still a markedly reticent man in mixed company, hampered as he was by his stammer and innate shyness. In 1897, Langdon-Brown invited Rivers to come and address the Abernethian Society. The occasion was not an unqualified success. He chose ‘Fatigue’ as his subject, and before he had finished his title was writ large on the faces of his audience. In the Cambridge physiological laboratory too he had to lecture to a large elementary class. He was rather nervous about it, and did not like it, his hesitation of speech made his style dry and he had not yet acquired the art of expressing his original ideas in an attractive form, except in private conversation.

Among two or three friends, however, the picture of Rivers is quite different. His conversations were full of interest and illumination; “he was always out to elicit the truth, entirely sincere, and disdainful of mere dialect.” His insistence on veracity made him a formidable researcher, as Haddon puts it, “the keynote of Rivers was thoroughness. Keenness of thought and precision marked all his work.”. His research was distinguished by a fidelity to the demands of experimental method very rare in the realms which he was exploring and, although often overlooked, the work that Rivers did in this early period is of immense import as it formed the foundation of all that came later.

and, while fond of St. John’s, the staid lifestyle of his Cambridge existence showed in signs of nervous strain and led him to experience periods of depression.

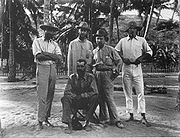

The turning point came in 1898 when Alfred Cort Haddon

seduced "Rivers from the path of virtue... (for psychology then was a chaste science)... into that of anthropology:” He made Rivers first choice to head an expedition to the Torres Straits. Rivers’s first reaction was to decline, but he soon agreed on learning that C.S Myers and William McDougall

, two of his best former students, would participate. The other members were Sidney Ray

, C.G Seligman

, and a young Cambridge graduate named Anthony Wilkin, who was asked to accompany the expedition as photographer. In April 1898, the Europeans were transported with gear and apparatus to the Torres Straits. Rivers was said to pack only a small handbag of personal effects for such field trips.

From Thursday Island, several of the party found passage, soaked by rain and waves, on the deck of a crowded 47-foot ketch

From Thursday Island, several of the party found passage, soaked by rain and waves, on the deck of a crowded 47-foot ketch

. In addition to sea sickness, Rivers had been badly sunburnt on his shins and for many days had been quite ill. On 5 May, in a bad storm nearing their first destination in the Murray Islands

, the ship dragged anchor on the Barrier Reef

and the expedition almost met disaster Later Rivers recalled the palliative effect of near shipwreck.

When the ketch dropped anchor, Rivers and Ray were at first too ill to go ashore. However the others set up a surgery to treat the native islanders and Rivers, lying in bed next-door tested the patients for colour vision: Haddon's diary noted "He is getting some interesting results.” The warmth shown to the sickly Rivers by the Islanders contributed to strong positive feelings for the work and a deep concern for the welfare of Melanesians during the remainder of his life.”

Rivers’s first task was to examine first hand the colour vision of the islanders and compare it to that of Europeans. In the course of his examinations of the visual acuity of the natives, Rivers showed that colour-blindness did not exist or was very rare, but that the colour vision of Papuans was not the same type as that of Europeans; they possessed no word for blue, and an intelligent native found nothing unnatural in applying the same name to the brilliant blue sea or sky and to the deepest black. “Moreover,” Head goes on to state in Rivers’s obituary notice, “he was able to explode to old fallacy that the “noble savage” was endowed with powers of vision far exceeding that of civilised natives. Errors of refraction are, it is true, less common, especially myopia. But, altogether the feats of the Torres Straits islanders equalled those reported by travellers from other parts of the world, they were due to the power of attending to minute details in familiar and strictly limited surrounding, and not to supernormal visual acuity.”

It was at this point that Rivers began collecting family histories and constructing genealogical tables but at this point his purpose appears to have been more biological than ethnological since such tables seem to have originated as a means of determining whether certain sensory talents or disabilities were hereditary. However, these simple tables soon took on a new prospective.

It was at once evident to Rivers that “the names applied to the various forms of blood relationship did not correspond to those used by Europeans, but belonged to what is known as a “classificatory system”; a man’s “brothers” or “sisters” might include individuals we should call cousins and the key to this nomenclature is to be found in forms of social organisation especially in varieties of the institution of marriage.” Rivers found that relationship terms were used to imply definite duties, privileges and mutual restrictions in conduct, rather than being biologically based as ours are. As Head puts it: “all these facts were clearly demonstrable by the genealogical method, a triumphant generalisation which has revolutionised ethnology.”

The Torres Straits expedition was ‘revolutionary’ in many other respects as well. For the first time, British anthropology had been removed from its ‘armchair’ and placed into a sound empirical basis, providing the model for future anthropologists to follow. In 1916, Sir Arthur Keith stated in an address to the Royal Anthropological Institute, that the expedition had engendered “the most progressive and profitable movement in the history of British anthropology.”

While the expedition was clearly productive and, in many ways, arduous for its members, it was also the foundation of lasting friendships. The team would reunite at many points and their paths would frequently converge. Of particular note is the relationship between Rivers and Haddon, the latter of whom regarded the fact he had induced Rivers to come to the Torres Straits as his “claim to fame.” It cannot be denied that both Rivers and Haddon were serious about their work but at the same time they were imbued with a keen sense of humour and fun. Haddon’s diary from Tuesday 16 August reads thus: “Our friends and acquaintances would often be very much amused if they could see us at some of our occupations ad I am afraid these would sometimes give occasion to the enemy to blaspheme- so trivial would they appear. Every now and then we then one thing hard- for example one week we were mad on Cat's cradle

- at least Rivers, Ray and I were- McDougall soon fell victim and even Myers eventually succumbed.”

It may seem to be a bizarre occupation for a group of highly qualified men of science, indeed, as Haddon states: “I can imagine that some people would think we were demented- or at least wasting our time.” However, both Haddon and Rivers were to use the string trick to scientific ends and they are also credited as inventing a system of nomenclature that enabled them to be able to schematise the steps required and teach a variety of string tricks to European audiences.

The expedition ended in October 1898 and Rivers returned to England.” In 1900, Rivers joined Myers and Wilkin in Egypt to run tests on the colour vision of the Egyptians; this was the last time he saw Wilkin, who died of dysentery

in May 1901, aged 24.

It quickly became clear to Rivers, looking in on the experiment from a psycho-physical aspect, that the only way accurate results could be obtained from introspection on behalf of the patient is if the subject under investigation was himself a trained observer, sufficiently discriminative to realise if his introspection was being prejudiced by external irrelevancies or moulded by the form of the experimenter’s questions, and sufficiently detached to lead a life of detachment throughout the entire course of the tests. It was in the belief that he could fulfil these requirements, that Head himself volunteered to act, as Langham puts it, “as Rivers’s experimental guinea-pig.”

So it was that, on the 25th of April 1903, the radial and external cutaneous nerves of Henry Head’s arm were severed and sutured. Rivers was then to take on the role of examiner and chart the regeneration of the nerves, considering the structure and functions of the nervous system from an evolutionary standpoint through a series of “precise and untiring observations” over a period of five years.

At first observation, the day after the operation, the back of Head’s hand and the dorsal surface of his thumb were seen to be “completely insensitive to stimulation with cotton wool, to pricking with a pin, and to all degrees of heat and cold.” While cutaneous sensibility had ceased, deep sensibility was maintained so that pressure with a finger, a pencil or with any blunt object was appreciated without hesitation.

So that the distractions of a busy life should not interfere with Head’s introspective analysis, it was decided that the experimentation should take place in Rivers’s rooms. Here, as Head states, “for five happy years we worked together on week-ends and holidays in the quiet atmosphere of his rooms at St. John’s College.” In the normal course of events, Head would travel to Cambridge on Saturday, after spending several hours on the outpatient department of the London Hospital. On these occasions, however, he would find that he was simply too exhausted to work on the Saturday evening so experimentation would have to be withheld until the Sunday. If, therefore, a long series of tests were to be carried out, Head would come to Cambridge on the Friday, returning to London on Monday morning. At some points, usually during Rivers’s vacation period, longer periods could be devoted to the observations. Between the date of the operation and their last sitting on the 13th December, 1907, 167 days were devoted to the investigation.

Since Head was simultaneously collaborator and experimental subject, extensive precautions were taken to make sure that no outside factors influenced his subjective appreciation of what he was perceiving: “No questions were asked until the termination of a series of events; for we found it was scarcely possible... to ask even simple questions without giving a suggestion either for or against the right answer... The clinking of ice against the glass, the removal of the kettle from the hob, tended to prejudice his answers... [Rivers] was therefore particularly careful to make all his preparations beforehand; the iced tubes were filled and jugs of hot and cold water ranged within easy reach of his hand, so that the water of the temperature required might be mixed silently.”

Moreover, although before each series of tests Head and Rivers would discuss their plan of action, Rivers was careful to vary this order to such an extent during the actual testing that Head would be unable to tell what was coming next.

Gradually during the course of the investigation, certain isolated spots of cutaneous sensibility began to appear; these spots were sensitive to heat, cold and pressure. However, the spaces between these spots remained insensitive at first, unless sensations- such as heat or cold- reached above a certain threshold at which point the feeling evoked was unpleasant and usually perceived as being “more painful” than it was if the same stimulus was applied to Head’s unaffected arm. Also, although the sensitive spots were quite definitely localised, Head, who sat through the tests with his eyes closed, was unable to gain any exact appreciation of the locus of stimulation. Quite the contrary, the sensations radiated widely, and Head tended to refer them to places remote from the actual point of stimulation.

This was the first stage of the recovery process and Head and Rivers dubbed it the ‘protopathic’, taking its origins from the Middle Greek word protopathes, meaning ‘first affected’. This protopathic stage seemed to be marked by an ‘all-or-nothing’ aspect since there was either an inordinate response to sensation when compared with normal reaction or no reaction whatever if the stimulation was below the threshold.

This was the first stage of the recovery process and Head and Rivers dubbed it the ‘protopathic’, taking its origins from the Middle Greek word protopathes, meaning ‘first affected’. This protopathic stage seemed to be marked by an ‘all-or-nothing’ aspect since there was either an inordinate response to sensation when compared with normal reaction or no reaction whatever if the stimulation was below the threshold.

Finally, when Head was able to distinguish between different temperatures and sensations below the threshold, and when he could recognise when two compass points were applied simultaneously to the skin, Head’s arm began to enter the second stage of recovery. They named this stage the ‘epicritic’, from the Greek epikritikos, meaning 'determinative'.

From an evolutionary perspective, it soon became clear to Rivers that the epicritic nervous reaction was the superior, as it suppressed and abolished all protopathic sensibility. This, Rivers found, was the case in all parts of the skin of the male anatomy except one area where protopathic sensibility is unimpeded by epicritic impulses: the glans penis

. As Langham points out, with special references to “Rivers’s reputed sexual proclivities”, it is at this point that the experiment takes on an almost farcical aspect to the casual reader. It may not seem surprising to us that when Rivers was to apply a needle to a particularly sensitive part of the glans that “pain appeared and was so excessively unpleasant that [Head] cried out and started away”; indeed, such a test could be seen as a futility verging on the masochistic. Nor would we necessarily equate the following passage with what one might normally find in a scientific text:

“The foreskin was drawn back, and the penis allowed to hang downwards. A number of drinking glasses were prepared containing water at different temperatures. [Head] stood with his eyes closed, and [Rivers] gradually approached one of the glasses until the surface of the water covered the glans but did not touch the foreskin. Contact with the fluid was not appreciated; if, therefore, the temperature of the water was such that it did not produce a sensation of heat or cold, Head was unaware that anything had been done.”

However, the investigations, bizarre as they may seem, did have a sound scientific basis since Rivers especially was looking at the protopathic and epicritic from an evolutionary perspective. From this standpoint it is intensely interesting to note that the male anatomy maintains one area which is ‘unevolved’ in so much as it is “associated with a more primitive form of sensibility”. Using this information about the protopathic areas of the human body, Rivers and Head then began to explore elements of man’s psyche. One way in which they did this was to examine the 'pilomoter reflex'

(the erection of hairs). Head and Rivers noted that the thrill evoked by aesthetic pleasure is “accompanied by the erection of hairs” and they noted that this reaction was no greater in the area of skin with protopathic sensibility than it was in the area of the more evolved epicritic, making it a purely psychologically based phenomena. As Langham puts it: “The image of a man reading a poem to evoke aesthetic pleasure while a close friend meticulously studies the erection of his hairs may seem ludicrous. However, it provides a neat encapsulation of Rivers’s desire to subject possibly protopathic phenomena to the discipline of rigorous investigation.”

and some others, Rivers founded the British Journal of Psychology of which he was at first joint editor.

From 1908 till the outbreak of the war Dr. Rivers was mainly preoccupied with ethnological and sociological problems. Already he had relinquished his official post as Lecturer in Experimental Psychology in favour of Dr. Charles Samuel Myers

, and now held only a lectureship on the physiology of the special senses. By degrees he became more absorbed in anthropological research. But though he was now an ethnologist rather than a psychologist he always maintained that what was of value in his work was due directly to his training in the psychological laboratory. In the laboratory he had learnt the importance of exact method; in the field he now gained vigor and vitality by his constant contact with the actual daily behaviour of human beings.

During 1907–8 Rivers travelled to the Solomon Islands

, and other areas of Melanesia

and Polynesia

. His two-volume History of Melanesian Society (1914), which he dedicated to St Johns, presented a diffusionist thesis for the development of culture in the south-west Pacific. In the year of publication he made a second journey to Melanesia, returning to England in March 1915, to find that war had broken out.

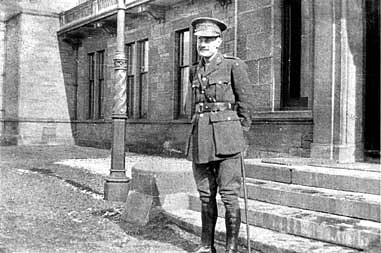

at Craiglockhart War Hospital near Edinburgh

, where he applied techniques of psychoanalysis

to British officers suffering from various forms of neurosis

brought on by their war experiences.

Rivers' methods are often, somewhat unfairly, said to have stemmed from Sigmund Freud

Rivers' methods are often, somewhat unfairly, said to have stemmed from Sigmund Freud

(essays such as http://www.freud.org.uk/warneuroses.htmlFreud and the War Neuroses: Pat Barker

's "Regeneration"] gladly compare the two) however, this is not truly the case as you can read both in Barker's novels and in the words of friends such as Myers. Although he was aware of Freud's theories and methods, he did not necessarily subscribe to them. (See Rivers' Conflict and Dream for his methods of dream analysis and his thoughts on Freud.) While he 'admitted', as Myers describes, 'the conflict of social factors with the sexual instincts in certain psychoneuroses' of civilian life, he saw the instinct of self-preservation rather than the sexual instinct, as the driving force behind war neuroses. Therefore he formed his 'talking cure', not on the basis that soldiers were repressing sexual urges, but rather their fear pertaining to their war experiences. As such, he really is a pioneer in his field - both for his new methods and for the fact that he went against the grain of the beliefs of the time (Shell shock

was not considered a 'real' illness and 'cures' mainly involved electric shock, with doctors such as Lewis Yealland

particularly keen on this form of 'treatment'). Rivers' treatment also went against the grain of the society in which he had been brought up - he did not advocate the traditional 'stiff upper-lip' approach but rather told his patients to express their emotions.

Sassoon came to him in 1917 after publicly protesting against the war and refusing to return to his regiment, but was treated with sympathy and given much leeway until he voluntarily returned to France. For Rivers, there was a considerable dilemma involved in 'curing' his patients simply in order that they could be sent back to the Western Front

to die. Rivers' feelings of guilt are clearly portrayed both in fiction and in fact. Through Pat Barker's novels and in Rivers' works (particularly Conflict and Dream) we get a sense of the turmoil the doctor went through. As Sassoon wrote in a letter to Robert Graves (24 July 1918):

He did not wish to 'break' his patients but at the same time he knew that it was their duty to return to the front and his duty to send them. There is also an implication (given the pun on Rivers' name along with other factors) that Rivers was more to Sassoon than just a friend, as he called him, 'father confessor', a point that Jean Moorcroft Wilson

picks up on in her biography of Sassoon, however Rivers' tight morals would have probably prevented such a relationship from progressing:

Not only Sassoon, but his patients as a whole, loved him and his colleague Frederic Bartlett

wrote of him

Sassoon described Rivers' bedside manner in his letter to Graves, written as he lay in hospital after being shot (a head wound that he had hoped would kill him- he was bitterly disappointed when it didn't):

He was well known for his compassionate, effective and pioneering treatments; as Sassoon's testimony reveals, he treated his patients very much as individuals. Rivers published the results of his experimental treatment of patients at Craiglockhart in a The Lancet

paper 'On the Repression of War Experience' and began to record interesting cases in his book 'Conflict and Dream' which was published a year after his death by his close friend Grafton Elliot Smith

.

Rivers had visited his college frequently during the war although, having resigned his position as lecturer, he held no official post. However, upon his return from the Royal Flying Corps in 1919, the college created a new office for him- 'Praelector of Natural Science Studies - and he was given a free rein to do as he pleased. As Leonard E. Shore recalled in 1923: He took his new position to be a mandate to get to know every science student and indeed every other student at St. Johns, Cambridge and at other colleges. He would arrange 'At Homes' in his rooms on Sunday evenings, as well as Sunday morning breakfast meetings; he also organised informal discussions and formal lectures (many of which he gave himself) in the College Hall. He formed a group called The Socratics and brought to it some of his most influential friends, including H. G. Wells

, Arnold Bennett

, Bertrand Russell

and Sassoon. Sassoon (Patient B in 'Conflict and Dream'), remained particularly friendly with Rivers and regarded him as a mentor. They shared Socialist sympathies.

Having already been made president of the anthropological section of the British Association for the Advancement of Science

Having already been made president of the anthropological section of the British Association for the Advancement of Science

in 1911, after the war he became president of the English Folk-Lore Society (1920), and the Royal Anthropological Institute (1921–1922). He was also awarded honorary degrees from the universities of Manchester, St. Andrews and Cambridge in 1919.

Rivers died of a strangulated hernia in the summer of 1922, shortly after being named as a Labour

candidate for the 1922 general election

. He had agreed to run for parliament, as he said:

He had been taken ill suddenly in his rooms at St John's on the evening of Friday 3 June, having sent his servant home to enjoy the summer festivities. By the time he was found in the morning, it was too late and he knew it. Typically for this man who, throughout his life "displayed a complete disregard for personal gain, he was selfless to the last. There is a document granting approval for the diploma in anthropology to be awarded as of Easter term, 1922, to an undergraduate student from India. It is signed by Haddon and Rivers dated 4 June 1922. At the bottom is a notation in Haddon's handwriting:

Rivers signed the papers as he lay dying in the Evelyn Nursing Home following an unsuccessful emergency operation. He had an extravagant funeral at St. John's in accordance with his wishes as he was an expert on funeral rites and was put to rest in All Souls Burial Ground, formerly the churchyard of St Giles

Church, Cambridge. Sassoon was deeply saddened by the death of his father figure and collapsed at his funeral. His loss prompted him to write two poignant poems about the man he had grown to love: "To A Very Wise Man" and "Revisitation".

not long after Rivers' death, he touches on the peace and security he felt in Rivers' rooms:

An anonymously written poem Anthropological Thoughts can be found in the Rivers collection of the Haddon archives at Cambridge. There is a reference that indicates that these lines were written by Charles Elliot Fox

, missionary and ethnographer friend of Rivers.

') Rivers is one of the few characters to retain their original names. There is a whole chapter devoted to Rivers and he is immortalised by Sassoon as a near demi-god who saved his life and his soul. Sassoon wrote:

Rivers was much loved and admired, not just by Sassoon. Bartlett wrote of his experiences of Rivers in one of his obituaries, as well as in many other articles (see 'References') as the man had a profound influence on his life:

Rivers' legacy continues even today in the form of The Rivers Centre, which treats patients suffering from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder using the same famously humane methods as Rivers had. There is also a Rivers Memorial Medal, founded in 1923, which is rewarded each year to an anthropologist who has made a significant impact in his or her field. Appropriately, Haddon was the first to receive this award in 1924.

Sassoon writes about Rivers in the third part of The Memoirs of George Sherston

, Sherston's Progress

. There is a chapter named after the doctor and Rivers appears in both books as the only character to retain his factual name, giving him a position as a sort of demi-god in Sassoon's semi-fictitious memoirs.

The life of W. H. R. Rivers and his encounter with Sassoon was fictionalised by Pat Barker

in the Regeneration Trilogy, a series of three books including Regeneration

(1991), The Eye in the Door

(1993) and The Ghost Road

(1995). The trilogy was greeted with considerable acclaim, with The Ghost Road being awarded the Booker Prize in the year of its publication. Regeneration was filmed in 1997 with Jonathan Pryce

in the role of Rivers.

The first book, Regeneration deals primarily with Rivers' treatment of Sassoon at Craiglockhart. In the novel we are introduced to Rivers as a doctor for whom healing patients comes at price. The dilemmas faced by Rivers are brought to the fore and the strain leads him to become ill; on sick leave he visits his brother and the Heads and we learn more about his relationships outside of hospital life. We are also introduced in the course of the novel to the Canadian doctor Lewis Yealland, another factual figure who used electric shock

treatment to 'cure' his patients. The juxtaposition of the two very different doctors highlights the unique, or at least unconventional, nature of Rivers' methods and the humane way in which he treated his patients (even though Yealland's words, and his own guilt and modesty lead him to think otherwise).

The Eye in the Door concentrates, for the most part, on Rivers' treatment of the fictional character of Prior. Although Prior's character might not have existed, the facts that he makes Rivers face up to did- that something happened to him on the first floor of his house that caused him to block all visual memory and begin to stammer. We also learn of Rivers' treatment of officers in the airforce and of his work with Head. Sassoon too plays a role in the book- Rivers visits him in hospital where he finds him to be a different, if not broken, man, his attempt at 'suicide' having failed. This second novel in the trilogy, both implicitly and directly, addresses the issue of Rivers' possible homosexuality and attraction to Sassoon. From Rivers' reaction to finding out that Sassoon is in hospital to the song playing in the background 'you made me love you' and Ruth Head's question to her husband "do you think he's in love with him?" we get a strong impression of the author's opinions on Rivers' sexuality.

The Ghost Road, the final part of the trilogy, shows a side of Rivers not previously seen in the novels. As well as showing his relationship with his sisters and father, we also learn of his feelings for Charles Dodgson- or Lewis Carroll. Carroll was the first adult Rivers met who stammered as badly as he did and yet he cruelly rejected him, preferring to lavish attention on his pretty young sisters. In this novel the reader also learns of Rivers' visit to Melenasia; feverish with Spanish Flu

, the doctor is able to recount the expedition and we are provided with insight both into the culture of the island and into Rivers' very different 'field trip personae'.

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

anthropologist, neurologist

Neurologist

A neurologist is a physician who specializes in neurology, and is trained to investigate, or diagnose and treat neurological disorders.Neurology is the medical specialty related to the human nervous system. The nervous system encompasses the brain, spinal cord, and peripheral nerves. A specialist...

, ethnologist and psychiatrist

Psychiatrist

A psychiatrist is a physician who specializes in the diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders. All psychiatrists are trained in diagnostic evaluation and in psychotherapy...

, best known for his work with shell-shocked

Post-traumatic stress disorder

Posttraumaticstress disorder is a severe anxiety disorder that can develop after exposure to any event that results in psychological trauma. This event may involve the threat of death to oneself or to someone else, or to one's own or someone else's physical, sexual, or psychological integrity,...

soldiers during World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

. Rivers' most famous patient was the poet Siegfried Sassoon

Siegfried Sassoon

Siegfried Loraine Sassoon CBE MC was an English poet, author and soldier. Decorated for bravery on the Western Front, he became one of the leading poets of the First World War. His poetry both described the horrors of the trenches, and satirised the patriotic pretensions of those who, in Sassoon's...

. He is also famous for his participation in the Torres Straits expedition of 1898, and his consequent seminal work on the subject of kinship

Kinship

Kinship is a relationship between any entities that share a genealogical origin, through either biological, cultural, or historical descent. And descent groups, lineages, etc. are treated in their own subsections....

.

Family background

Rivers was born in 1864 at Constitution Hill, Chatham, Kent, son of Elizabeth Hunt (16 October 1834- 13 November 1897) and Henry Frederick Rivers (7 January 1830– 9 December 1911).Records from the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries show the Rivers family to be solidly middle-class with many Cambridge

University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a public research university located in Cambridge, United Kingdom. It is the second-oldest university in both the United Kingdom and the English-speaking world , and the seventh-oldest globally...

, Church of England

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

and Royal Navy

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

associations, the most famous of which were Midshipman

Midshipman

A midshipman is an officer cadet, or a commissioned officer of the lowest rank, in the Royal Navy, United States Navy, and many Commonwealth navies. Commonwealth countries which use the rank include Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, India, Pakistan, Singapore, Sri Lanka and Kenya...

William Rivers and his father Gunner

Sailor

A sailor, mariner, or seaman is a person who navigates water-borne vessels or assists in their operation, maintenance, or service. The term can apply to professional mariners, military personnel, and recreational sailors as well as a plethora of other uses...

Rivers who both served aboard HMS Victory

HMS Victory

HMS Victory is a 104-gun first-rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, laid down in 1759 and launched in 1765. She is most famous as Lord Nelson's flagship at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805....

.

.jpg)

Battle of Trafalgar

The Battle of Trafalgar was a sea battle fought between the British Royal Navy and the combined fleets of the French Navy and Spanish Navy, during the War of the Third Coalition of the Napoleonic Wars ....

. In the course of his duties, the seventeen-year-old midshipman’s foot was almost completely blown off by a grenade, left attached to him ‘by a Piece of Skin abought 4 inch above the ankle’. Rivers asked first for his shoes, then told the gunner’s mate to look after the guns and informed Captain Hardy that he was going down to the cockpit. The leg was then sawn off, without anaesthetic, four inches below the knee. According to legend, he did not cry out once during the amputation nor during the consequent sealing of the wound with hot tar. When Gunner Rivers, anxious about his son’s welfare, went to the cockpit to ask after him the young man called out from the other side of the deck, ‘Here I am, Father, nothing is the matter with me; only lost my leg and that in a good cause.’ After the Battle, the senior Rivers wrote a poem about his remarkable son entitled ‘Lines on a Young Gentleman that lost his leg onboard the Victory in the Glorious action at Trafalgar’:

Born to another naval Rivers, Lt. William Rivers, R.N., then stationed at Deptford

Deptford

Deptford is a district of south London, England, located on the south bank of the River Thames. It is named after a ford of the River Ravensbourne, and from the mid 16th century to the late 19th was home to Deptford Dockyard, the first of the Royal Navy Dockyards.Deptford and the docks are...

, Henry Rivers followed many family traditions in being educated at Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Trinity has more members than any other college in Cambridge or Oxford, with around 700 undergraduates, 430 graduates, and over 170 Fellows...

and entering the church. Having earned his Bachelor of Arts in 1857, he was ordained as a Church of England priest in 1858, a career that would span almost 50 years until, in 1904, he was forced to tender his resignation due to ‘infirmities of sight and memory’.

Hastings

Hastings is a town and borough in the county of East Sussex on the south coast of England. The town is located east of the county town of Lewes and south east of London, and has an estimated population of 86,900....

, not far from Chatham.

The Hunts, like the Riverses, were an established naval and Church of England family. One of those destined for the pulpit was Thomas (1802–1851), but some quirk of originality set him off into an unusual career. While an undergraduate at Cambridge, Thomas Hunt had a friend who stammered badly and his efforts to aid the afflicted student led him to leave the University without taking a degree in order to make a thorough study of speech and its defects. He built up a good practise as a speech therapist and was patronised by Sir John Forbes MD FRS

John Forbes (physician)

Sir John Forbes FRCP FRS was a distinguished Scottish physician, famous for his translation of the classic French medical text, De L'Auscultation Mediate by René Laennec, the inventor of the stethoscope...

, who sent him pupils for twenty four years. Hunt’s most famous case came about in 1842 when George Pearson, the chief witness in the case respecting the attempt on the life of Queen Victoria made by John Francis, was brought into court he was incapable of giving his evidence. However, after just a fortnight's instruction from Hunt he spoke easily, a fact certified by the sitting magistrate. Hunt died in 1851, survived by his wife Mary and their two children. His practise was then passed on to his son, James.

James Hunt (1833–1869) was an exuberant character, giving to each of his ventures his boundless energy and self-confidence. Taking up his father’s legacy with great zeal, by the age of 21 Hunt had published his compendious work, "Stammering and Stuttering, Their Nature and Treatment". This went into six editions during his lifetime and was reprinted again in 1870, just after his death, and for an eighth time in 1967 as a landmark in the history of speech therapy. In the introduction to the 1967 edition of the book, Elliot Schaffer notes that in his short lifetime James Hunt is said to have treated over 1,700 cases of speech impediment, firstly in his father’s practise and later at his own institute, Ore House near Hastings, which he set up with the aid a doctorate he had purchased in 1856 from the University of Giessen

University of Giessen

The University of Giessen is officially called the Justus Liebig University Giessen after its most famous faculty member, Justus von Liebig, the founder of modern agricultural chemistry and inventor of artificial fertiliser.-History:The University of Gießen is among the oldest institutions of...

in Germany.

In later, expanded editions, "Stammering and Stuttering" begins to reflect Hunt’s growing passion for anthropology exploring, as it does, the nature of language usage and speech disorders in non-European peoples. In 1856, Hunt had joined the Ethnological Society of London

Ethnological Society of London

The Ethnological Society of London was founded in 1843 by a breakaway faction of the Aborigines' Protection Society . It quickly became one of England's leading scientific societies, and a meeting-place not only for students of ethnology but also for archaeologists interested in prehistoric...

and by 1859 he was its joint secretary. He was not, however, a popular man within the society as many of the members disliked his attacks on religious and humanitarian agencies represented by missionaries and the anti-slavery movement.

As a result of the antagonism, Hunt founded the Anthropological Society

Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland

The Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland is the world's longest established anthropological organization, with a global membership. Since 1843, it has been at the forefront of new developments in anthropology and new means of communicating them to a broad audience...

and became its president, a position that would be taken up by his nephew almost sixty years later. It was mainly to do with Hunt’s efforts that the British Association for the Advancement of Science

British Association for the Advancement of Science

frame|right|"The BA" logoThe British Association for the Advancement of Science or the British Science Association, formerly known as the BA, is a learned society with the object of promoting science, directing general attention to scientific matters, and facilitating interaction between...

(BAAS) accepted anthropology in 1866.

Even by Victorian standards, Hunt was a decided racist. His paper "On a Negro’s Place in Nature", delivered before the BAAS in 1863, was met with hisses and catcalls. What Hunt saw as “a statement of the simple facts” was in fact a defence of the subjection and slavery of African-Americans and a support of the belief in the plurality of human species.

In addition to his extremist views, Hunt also led his society to incur heavy debts. The controversies surrounding his conduct told on his health and, on the 29th of August 1869, Hunt died of ‘inflammation of the brain’ leaving a widow, Henrietta Maria, and five children.

Hunt’s speech therapy practise was passed onto Hunt’s brother-in-law, Henry Rivers, who had been working with him for some time. With the practise came many of Hunt’s established patients, most notably The Reverend Charles L. Dodgson (better known as Lewis Carroll

Lewis Carroll

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson , better known by the pseudonym Lewis Carroll , was an English author, mathematician, logician, Anglican deacon and photographer. His most famous writings are Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and its sequel Through the Looking-Glass, as well as the poems "The Hunting of the...

) who had been a regular visitor to Ore House.

To his nephew William, Hunt had left his books though a young Rivers had refused them, thinking that they would be of no use to him.

Early life

William Halse Rivers Rivers was the oldest of four children, with his siblings being brother Charles Hay (29 August 1865- 8 November 1939) and sisters Ethel Marian (30 October 1867- 4 February 1943) and Katharine Elizabeth (1871–1939).

Rivers suffered from a stammer that never truly left him, he also had no sensory memory

Sensory memory

During every moment of an organism's life, sensory information is being taken in by sensory receptors and processed by the nervous system. Humans have five main senses: sight, hearing, taste, smell, and touch. Sensory memory allows individuals to retain impressions of sensory information after the...

although he was able to visualise to an extent if dreaming, in a half-waking, half-sleeping state or when feverish. This had not always been the case; Rivers notes that in his early life- specifically before the age of five- his visual imagery was far more definite than it became in later life and perhaps as good as that of the average child.

At first, Rivers had concluded that his loss of visual imagery had come about as a result of his lack of attention and interest in it. However, as he later came to realise, while images from his later life frequently faded into obscurity, those from his infancy still remained vivid.

As Rivers notes in Instinct and the Unconscious, one manifestation of his lack of visual memory was his inability to visualise any part of the upper floor of the house he lived in until he was five. This visual blank is made even more significant by the fact that Rivers was able to describe the lower floors of that particular house with far more accuracy than he had been able to with any house since and, although images of later houses were faded and incomplete, no memory since had been as inaccessible as that of the upper floor of his early home. With the evidence that he was presented with, Rivers was led to the conclusion that something had happened to him on the upper floor of that house, the memory of which was entirely suppressed because it ‘interfered with [his] comfort and happiness’. Indeed, not only was that specific memory rendered inaccessible but his sensory memory in general appears to have been severely handicapped from that moment.

If Rivers ever did come to access the veiled memory then he does not appear to make a note of it so the nature of the experience is open to conjecture. One such supposition was put forward by Pat Barker, in the second novel in her Regeneration Trilogy, The Eye in the Door

The Eye in the Door

The Eye in the Door is a novel by Pat Barker, first published in 1993, and forming the second part of the Regeneration trilogy.The Eye in the Door is set in London, beginning in mid-April, 1918, and continues the interwoven stories of Dr William Rivers, Billy Prior, and Siegfried Sassoon begun in...

. Whatever the case, in the words of Barker's character Billy Prior, Rivers’ experience was traumatic enough to cause him to "put his mind's eye out".

Whatever his disadvantages, Rivers was an unquestionably able child. Educated first at a Brighton preparatory school and then, from the age of thirteen, as a dayboy at the prestigious Tonbridge School

Tonbridge School

Tonbridge School is a British boys' independent school for both boarding and day pupils in Tonbridge, Kent, founded in 1553 by Sir Andrew Judd . It is a member of the Eton Group, and has close links with the Worshipful Company of Skinners, one of the oldest London livery companies...

, his academic abilities were noted from an early age. Young Rivers’ talents led to him being placed a year above others of his age at school and even within this older group he was seen to excel, winning prizes for Classics

Classics

Classics is the branch of the Humanities comprising the languages, literature, philosophy, history, art, archaeology and other culture of the ancient Mediterranean world ; especially Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome during Classical Antiquity Classics (sometimes encompassing Classical Studies or...

and all around attainment. It is also worth noting that Rivers’ younger brother Charles was also a high achiever at the school; he too was awarded with the ‘Good Work’ prize and would go on to become a civil engineer

Civil engineer

A civil engineer is a person who practices civil engineering; the application of planning, designing, constructing, maintaining, and operating infrastructures while protecting the public and environmental health, as well as improving existing infrastructures that have been neglected.Originally, a...

until, after a bad bout of malaria

Malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease of humans and other animals caused by eukaryotic protists of the genus Plasmodium. The disease results from the multiplication of Plasmodium parasites within red blood cells, causing symptoms that typically include fever and headache, in severe cases...

contracted whilst in the Torres Straits with his brother, he was prompted by the elder Rivers to take up outdoor work.

The teenage Rivers, whilst obviously scholarly, was also involved in other aspects of school life. As the programme for the Tonbridge School sports day notes, on the 12th March 1880- Rivers’ sixteenth birthday- he ran in the mile race. The year before this he had been elected as a member of the school debating society, no mean feat for a boy who at this time suffered from a speech impediment which was almost paralytic.

University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a public research university located in Cambridge, United Kingdom. It is the second-oldest university in both the United Kingdom and the English-speaking world , and the seventh-oldest globally...

entrance exam, possibly with the aim of studying Classics. Unfortunately, his plans were thwarted when, at the age of sixteen, he was struck down by typhoid fever

Typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known as Typhoid, is a common worldwide bacterial disease, transmitted by the ingestion of food or water contaminated with the feces of an infected person, which contain the bacterium Salmonella enterica, serovar Typhi...

and forced to miss his final year of school. Without the scholarship, his family could not afford to send him to Cambridge but with typical resilience, Rivers did not dwell on the disappointment.

His illness had been a bad one, entailing long convalescence and leaving him with effects which at times severely handicapped him. As L. E. Shore notes: “he was not a strong man, and was often obliged to take a few days rest in bed and subsist on a milk diet”. The severity of the sickness and the shattering of dreams might have broken lesser men but for Rivers in many ways the illness was the making of him. Whilst recovering from the fever, Rivers had formed a friendship with one of his father’s speech therapy students, a young Army surgeon. His plan was formed: he would study medicine and apply for training in the Army Medical Department, later to become the Royal Army Medical Corps

Royal Army Medical Corps

The Royal Army Medical Corps is a specialist corps in the British Army which provides medical services to all British Army personnel and their families in war and in peace...

.

Fuelled by this new resolve, Rivers studied medicine at the University of London

University of London

-20th century:Shortly after 6 Burlington Gardens was vacated, the University went through a period of rapid expansion. Bedford College, Royal Holloway and the London School of Economics all joined in 1900, Regent's Park College, which had affiliated in 1841 became an official divinity school of the...

, where he matriculated in 1882, and St Bartholomew's Hospital

St Bartholomew's Hospital

St Bartholomew's Hospital, also known as Barts, is a hospital in Smithfield in the City of London, England.-Early history:It was founded in 1123 by Raherus or Rahere , a favourite courtier of King Henry I...

in London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

. He graduated aged just 22, the youngest person to do so until recent times.

Life as a ship's surgeon

After qualifying, Rivers sought to follow his ambition and join the army but was not passed fit. Once again the Typhoid had denied him his dreams. As Elliot Smith was later to write, as quoted in Rivers' biography: “Rivers always had to fight against ill health: heart and blood vessels.’’ Along with the health problems noted by Shore and Elliot Smith, Rivers had been left to the curse of "tiring easily".His sister Katharine wrote that when he came to visit the family he would often sleep for the first day or two. Astonishingly, considering the work that Rivers did in his relatively short lifetime, Seligman wrote in 1922 that "for many years he seldom worked for more than four hours a day". As Rivers' biographer Richard Slobodin points out, “among persons of extraordinary achievement, only Descartes seems to have put in as short a working day”.

As ever, Rivers did not allow his drawbacks to dishearten him", and instead of entering the army his love of travelling lead him to serve several terms as a ship's surgeon, travelling to Japan and North America in 1887. This was the first of many voyages; for, besides his great expeditions for work in the Torres Straits, Melanesia

Melanesia

Melanesia is a subregion of Oceania extending from the western end of the Pacific Ocean to the Arafura Sea, and eastward to Fiji. The region comprises most of the islands immediately north and northeast of Australia...

, Egypt

Egypt

Egypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

, India

India

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

and the Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands is a sovereign state in Oceania, east of Papua New Guinea, consisting of nearly one thousand islands. It covers a land mass of . The capital, Honiara, is located on the island of Guadalcanal...

, he took holiday voyages twice to the West Indies, three times to the Canary Islands

Canary Islands

The Canary Islands , also known as the Canaries , is a Spanish archipelago located just off the northwest coast of mainland Africa, 100 km west of the border between Morocco and the Western Sahara. The Canaries are a Spanish autonomous community and an outermost region of the European Union...

and Madeira

Madeira