William L. Laurence

Encyclopedia

William Leonard Laurence (March 7, 1888 – March 19, 1977) was a Jewish Lithuania

n born American

journalist

known for his science journalism writing of the 1940s and 1950s while working for the New York Times. He received two Pulitzer Prize

s, and as the official journalist of the Manhattan Project

was the only journalist to witness the Trinity test

and the atomic bombing of Nagasaki

. He is credited with coining the iconic phrase "Atomic Age

" which became popular in the 1950s.

, then part of Russia

though now in Lithuania

, and emigrated to the United States

in 1905 after participating in the Russian Revolution of 1905

. His name was originally Leib Wolf Siew, but he changed it after immigrating, taking "William" after William Shakespeare

, "Leonard" after Leonardo da Vinci

, and "Lawrence" after a street he lived on in Roxbury, Massachusetts

(he changed the "w" to a "u" in reference to Friedrich Schiller

's Laura). He attended college at Harvard University

, Harvard Law School

, and Boston University

, and became a naturalized United States citizen in 1913. During World War I

, he served with the U.S. Army Signal Corps, and in 1919 attended the University of Besançon in France

.

In 1926 he began his career as a journalist, working for The New York World

. In 1930 he began working at The New York Times

, specializing where possible in reporting on scientific issues. He married Florence Davidow in 1931.

In 1934, Laurence co-founded the National Association of Science Writers

, and in 1936 he covered the Harvard Tercenary Conference of Arts and Sciences, work for which he and four other science reporters received the 1937 Pulitzer Prize

in Journalism.

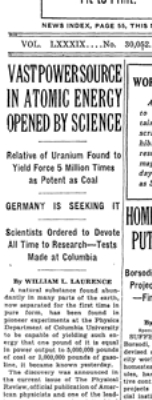

which were reported in Physical Review

, and outlined many (somewhat hyperbolic) claims about the possible future of nuclear power

. He had assembled it in part out of his own fear that Nazi Germany

was attempting to develop atomic energy, and had hoped the article would galvanize a U.S. effort. Though his article had no effect on the U.S. bomb program, it was passed to the Soviet mineralogist Vladimir Vernadsky

by his son, a professor of history at Yale University

, and motivated Vernadsky to urge Soviet authorities to embark on their own atomic program and established one of the first commissions to formulate "a plan of measures which it would be necessary to realize in connection with the possibility of using intraatomic energy" (no full-scale atomic energy program began in the Soviet Union until after the war, however).

In April 1945, Laurence was summoned to the secret Los Alamos laboratory

in New Mexico

by General Leslie Groves

to serve as the official journalist of the Manhattan Project

. In this capacity he was also the author of many of the first official press releases about nuclear weapon

s, including some delivered by the Department of War and President Harry S. Truman

. He was the only journalist present at the Trinity test

in July 1945, and beforehand prepared statements to be delivered in case the test ended in a disaster which killed those involved. As part of his work related to the Project, he also interviewed the airmen who flew on the mission to drop the atomic bomb on the city of Hiroshima

, Japan

. Laurence himself flew along on an observational plane for the atomic bombing of Nagasaki

. He visited the Test Able site at Bikini Atoll

aboard the press ship, 'Appalachian', for the bomb test on July 1, 1946.

For his wartime coverage, he received a Pulitzer Prize

in 1946. At the office of the Times he was thereafter referred to as "Atomic Bill", to differentiate him from William H. Lawrence, a political reporter at the newspaper.

In his autobiography, Richard Feynman

mentioned William Laurence standing next to him during the Trinity test. Feynman stated, "I had been the one who was supposed to have taken him around. Then it was found that it was too technical for him, and so later H.D. Smyth came and I showed him around."

In 1946, he published an account of the Trinity test as Dawn Over Zero, which went through at least two revisions. He continued to work at the Times through the 1940s and into the 1950s, and published a book on defense against nuclear war in 1950. In 1951, his book The Hell Bomb warned about the use of a cobalt bomb

— a form of hydrogen bomb (still an untested device at the time he wrote it) engineered to produce a maximum amount of nuclear fallout

.

In 1956, he was present at the testing of a hydrogen bomb at the Pacific Proving Grounds

. That same year, he also became appointed Science Editor of the New York Times, succeeding Waldemar Kaempffert

. He served in this capacity until he retired in 1964.

, of complications from a blood clot in his brain.

and David Goodman called for the Pulitzer Board to strip Laurence and his paper, The New York Times, of his 1946 Pulitzer Prize. The journalists wrote that at the time Laurence "was also on the payroll of War Department"" and that, after the atomic bombings, he “had a front-page story in the Times disputing the notion that radiation sickness

was killing people." They concluded that "his faithful parroting of the government line was crucial in launching a half-century of silence about the deadly lingering effects of the bomb

”.

Laurence denied that the black rain fallout in Hiroshima was significantly radioactive because it originated from the firestorm that began 30 minutes after explosion, when the radioactive mushroom cloud had been blown many miles downwind.

In their book Hiroshima in America: Fifty Years of Denial from 1995, Robert Jay Lifton and Greg Mitchell wrote, "Here was the nation's leading science reporter, severely compromised, not only unable but disinclined to reveal all he knew about the potential hazards of the most important scientific discovery of his time."

Lithuania

Lithuania , officially the Republic of Lithuania is a country in Northern Europe, the biggest of the three Baltic states. It is situated along the southeastern shore of the Baltic Sea, whereby to the west lie Sweden and Denmark...

n born American

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

journalist

Journalist

A journalist collects and distributes news and other information. A journalist's work is referred to as journalism.A reporter is a type of journalist who researchs, writes, and reports on information to be presented in mass media, including print media , electronic media , and digital media A...

known for his science journalism writing of the 1940s and 1950s while working for the New York Times. He received two Pulitzer Prize

Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prize is a U.S. award for achievements in newspaper and online journalism, literature and musical composition. It was established by American publisher Joseph Pulitzer and is administered by Columbia University in New York City...

s, and as the official journalist of the Manhattan Project

Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program, led by the United States with participation from the United Kingdom and Canada, that produced the first atomic bomb during World War II. From 1942 to 1946, the project was under the direction of Major General Leslie Groves of the US Army...

was the only journalist to witness the Trinity test

Trinity test

Trinity was the code name of the first test of a nuclear weapon. This test was conducted by the United States Army on July 16, 1945, in the Jornada del Muerto desert about 35 miles southeast of Socorro, New Mexico, at the new White Sands Proving Ground, which incorporated the Alamogordo Bombing...

and the atomic bombing of Nagasaki

Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

During the final stages of World War II in 1945, the United States conducted two atomic bombings against the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan, the first on August 6, 1945, and the second on August 9, 1945. These two events are the only use of nuclear weapons in war to date.For six months...

. He is credited with coining the iconic phrase "Atomic Age

Atomic Age

The Atomic Age, also known as the Atomic Era, is a phrase typically used to delineate the period of history following the detonation of the first nuclear bomb Trinity on July 16, 1945...

" which became popular in the 1950s.

Biography

Laurence was born in SalantaiSalantai

Salantai is a small city in Lithuania. It is located in the Klaipėda County, Kretinga district.-History:This town is known for two famed rabbis: Rabbi Yisrael Lipkin Salanter and his teacher Rabbi Zundel Salant, who spent most of his life in Salantai....

, then part of Russia

Russia

Russia or , officially known as both Russia and the Russian Federation , is a country in northern Eurasia. It is a federal semi-presidential republic, comprising 83 federal subjects...

though now in Lithuania

Lithuania

Lithuania , officially the Republic of Lithuania is a country in Northern Europe, the biggest of the three Baltic states. It is situated along the southeastern shore of the Baltic Sea, whereby to the west lie Sweden and Denmark...

, and emigrated to the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

in 1905 after participating in the Russian Revolution of 1905

Russian Revolution of 1905

The 1905 Russian Revolution was a wave of mass political and social unrest that spread through vast areas of the Russian Empire. Some of it was directed against the government, while some was undirected. It included worker strikes, peasant unrest, and military mutinies...

. His name was originally Leib Wolf Siew, but he changed it after immigrating, taking "William" after William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare was an English poet and playwright, widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's national poet and the "Bard of Avon"...

, "Leonard" after Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci was an Italian Renaissance polymath: painter, sculptor, architect, musician, scientist, mathematician, engineer, inventor, anatomist, geologist, cartographer, botanist and writer whose genius, perhaps more than that of any other figure, epitomized the Renaissance...

, and "Lawrence" after a street he lived on in Roxbury, Massachusetts

Roxbury, Massachusetts

Roxbury is a dissolved municipality and current neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts, United States. It was one of the first towns founded in the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630, and became a city in 1846 until annexed to Boston on January 5, 1868...

(he changed the "w" to a "u" in reference to Friedrich Schiller

Friedrich Schiller

Johann Christoph Friedrich von Schiller was a German poet, philosopher, historian, and playwright. During the last seventeen years of his life , Schiller struck up a productive, if complicated, friendship with already famous and influential Johann Wolfgang von Goethe...

's Laura). He attended college at Harvard University

Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League university located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States, established in 1636 by the Massachusetts legislature. Harvard is the oldest institution of higher learning in the United States and the first corporation chartered in the country...

, Harvard Law School

Harvard Law School

Harvard Law School is one of the professional graduate schools of Harvard University. Located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, it is the oldest continually-operating law school in the United States and is home to the largest academic law library in the world. The school is routinely ranked by the U.S...

, and Boston University

Boston University

Boston University is a private research university located in Boston, Massachusetts. With more than 4,000 faculty members and more than 31,000 students, Boston University is one of the largest private universities in the United States and one of Boston's largest employers...

, and became a naturalized United States citizen in 1913. During World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, he served with the U.S. Army Signal Corps, and in 1919 attended the University of Besançon in France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

.

In 1926 he began his career as a journalist, working for The New York World

New York World

The New York World was a newspaper published in New York City from 1860 until 1931. The paper played a major role in the history of American newspapers...

. In 1930 he began working at The New York Times

The New York Times

The New York Times is an American daily newspaper founded and continuously published in New York City since 1851. The New York Times has won 106 Pulitzer Prizes, the most of any news organization...

, specializing where possible in reporting on scientific issues. He married Florence Davidow in 1931.

In 1934, Laurence co-founded the National Association of Science Writers

National Association of Science Writers

The National Association of Science Writers was created in 1934 by a dozen science journalists and reporters in New York City. The aim of the organization was to improve the craft of science journalism and to promote good science reportage....

, and in 1936 he covered the Harvard Tercenary Conference of Arts and Sciences, work for which he and four other science reporters received the 1937 Pulitzer Prize

Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prize is a U.S. award for achievements in newspaper and online journalism, literature and musical composition. It was established by American publisher Joseph Pulitzer and is administered by Columbia University in New York City...

in Journalism.

"Atomic Bill"

In May 1940, Laurence published a front-page exclusive in the New York Times on successful attempts in isolating uranium-235Uranium-235

- References :* .* DOE Fundamentals handbook: Nuclear Physics and Reactor theory , .* A piece of U-235 the size of a grain of rice can produce energy equal to that contained in three tons of coal or fourteen barrels of oil. -External links:* * * one of the earliest articles on U-235 for the...

which were reported in Physical Review

Physical Review

Physical Review is an American scientific journal founded in 1893 by Edward Nichols. It publishes original research and scientific and literature reviews on all aspects of physics. It is published by the American Physical Society. The journal is in its third series, and is split in several...

, and outlined many (somewhat hyperbolic) claims about the possible future of nuclear power

Nuclear power

Nuclear power is the use of sustained nuclear fission to generate heat and electricity. Nuclear power plants provide about 6% of the world's energy and 13–14% of the world's electricity, with the U.S., France, and Japan together accounting for about 50% of nuclear generated electricity...

. He had assembled it in part out of his own fear that Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

was attempting to develop atomic energy, and had hoped the article would galvanize a U.S. effort. Though his article had no effect on the U.S. bomb program, it was passed to the Soviet mineralogist Vladimir Vernadsky

Vladimir Vernadsky

Vladimir Ivanovich Vernadsky was a Russian/Ukrainian and Soviet mineralogist and geochemist who is considered one of the founders of geochemistry, biogeochemistry, and of radiogeology. His ideas of noosphere were an important contribution to Russian cosmism. He also worked in Ukraine where he...

by his son, a professor of history at Yale University

Yale University

Yale University is a private, Ivy League university located in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701 in the Colony of Connecticut, the university is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States...

, and motivated Vernadsky to urge Soviet authorities to embark on their own atomic program and established one of the first commissions to formulate "a plan of measures which it would be necessary to realize in connection with the possibility of using intraatomic energy" (no full-scale atomic energy program began in the Soviet Union until after the war, however).

In April 1945, Laurence was summoned to the secret Los Alamos laboratory

Los Alamos National Laboratory

Los Alamos National Laboratory is a United States Department of Energy national laboratory, managed and operated by Los Alamos National Security , located in Los Alamos, New Mexico...

in New Mexico

New Mexico

New Mexico is a state located in the southwest and western regions of the United States. New Mexico is also usually considered one of the Mountain States. With a population density of 16 per square mile, New Mexico is the sixth-most sparsely inhabited U.S...

by General Leslie Groves

Leslie Groves

Lieutenant General Leslie Richard Groves, Jr. was a United States Army Corps of Engineers officer who oversaw the construction of the Pentagon and directed the Manhattan Project that developed the atomic bomb during World War II. As the son of a United States Army chaplain, Groves lived at a...

to serve as the official journalist of the Manhattan Project

Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program, led by the United States with participation from the United Kingdom and Canada, that produced the first atomic bomb during World War II. From 1942 to 1946, the project was under the direction of Major General Leslie Groves of the US Army...

. In this capacity he was also the author of many of the first official press releases about nuclear weapon

Nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission or a combination of fission and fusion. Both reactions release vast quantities of energy from relatively small amounts of matter. The first fission bomb test released the same amount...

s, including some delivered by the Department of War and President Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman was the 33rd President of the United States . As President Franklin D. Roosevelt's third vice president and the 34th Vice President of the United States , he succeeded to the presidency on April 12, 1945, when President Roosevelt died less than three months after beginning his...

. He was the only journalist present at the Trinity test

Trinity test

Trinity was the code name of the first test of a nuclear weapon. This test was conducted by the United States Army on July 16, 1945, in the Jornada del Muerto desert about 35 miles southeast of Socorro, New Mexico, at the new White Sands Proving Ground, which incorporated the Alamogordo Bombing...

in July 1945, and beforehand prepared statements to be delivered in case the test ended in a disaster which killed those involved. As part of his work related to the Project, he also interviewed the airmen who flew on the mission to drop the atomic bomb on the city of Hiroshima

Hiroshima

is the capital of Hiroshima Prefecture, and the largest city in the Chūgoku region of western Honshu, the largest island of Japan. It became best known as the first city in history to be destroyed by a nuclear weapon when the United States Army Air Forces dropped an atomic bomb on it at 8:15 A.M...

, Japan

Japan

Japan is an island nation in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean, it lies to the east of the Sea of Japan, China, North Korea, South Korea and Russia, stretching from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea and Taiwan in the south...

. Laurence himself flew along on an observational plane for the atomic bombing of Nagasaki

Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

During the final stages of World War II in 1945, the United States conducted two atomic bombings against the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan, the first on August 6, 1945, and the second on August 9, 1945. These two events are the only use of nuclear weapons in war to date.For six months...

. He visited the Test Able site at Bikini Atoll

Bikini Atoll

Bikini Atoll is an atoll, listed as a World Heritage Site, in the Micronesian Islands of the Pacific Ocean, part of Republic of the Marshall Islands....

aboard the press ship, 'Appalachian', for the bomb test on July 1, 1946.

For his wartime coverage, he received a Pulitzer Prize

Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prize is a U.S. award for achievements in newspaper and online journalism, literature and musical composition. It was established by American publisher Joseph Pulitzer and is administered by Columbia University in New York City...

in 1946. At the office of the Times he was thereafter referred to as "Atomic Bill", to differentiate him from William H. Lawrence, a political reporter at the newspaper.

In his autobiography, Richard Feynman

Richard Feynman

Richard Phillips Feynman was an American physicist known for his work in the path integral formulation of quantum mechanics, the theory of quantum electrodynamics and the physics of the superfluidity of supercooled liquid helium, as well as in particle physics...

mentioned William Laurence standing next to him during the Trinity test. Feynman stated, "I had been the one who was supposed to have taken him around. Then it was found that it was too technical for him, and so later H.D. Smyth came and I showed him around."

In 1946, he published an account of the Trinity test as Dawn Over Zero, which went through at least two revisions. He continued to work at the Times through the 1940s and into the 1950s, and published a book on defense against nuclear war in 1950. In 1951, his book The Hell Bomb warned about the use of a cobalt bomb

Cobalt bomb

A cobalt bomb is a theoretical type of "salted bomb": a nuclear weapon intended to contaminate an area by radioactive material, with a relatively small blast....

— a form of hydrogen bomb (still an untested device at the time he wrote it) engineered to produce a maximum amount of nuclear fallout

Nuclear fallout

Fallout is the residual radioactive material propelled into the upper atmosphere following a nuclear blast, so called because it "falls out" of the sky after the explosion and shock wave have passed. It commonly refers to the radioactive dust and ash created when a nuclear weapon explodes...

.

In 1956, he was present at the testing of a hydrogen bomb at the Pacific Proving Grounds

Pacific Proving Grounds

The Pacific Proving Grounds was the name used to describe a number of sites in the Marshall Islands and a few other sites in the Pacific Ocean, used by the United States to conduct nuclear testing at various times between 1946 and 1962...

. That same year, he also became appointed Science Editor of the New York Times, succeeding Waldemar Kaempffert

Waldemar Kaempffert

Waldemar Kaempffert was a US science writer and museum director.Waldemar Kaempffert was born and raised in New York City. He received his B.S. from the City College of New York in 1897. Thereafter he was employed by Scientific American, first as a translator , then as managing editor...

. He served in this capacity until he retired in 1964.

Death

Laurence died in 1977 in Majorca, SpainSpain

Spain , officially the Kingdom of Spain languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Spain's official name is as follows:;;;;;;), is a country and member state of the European Union located in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula...

, of complications from a blood clot in his brain.

Call for revocation of 1946 Pulitzer Prize

In 2004, journalists Amy GoodmanAmy Goodman

Amy Goodman is an American progressive broadcast journalist, syndicated columnist, investigative reporter and author. Goodman is the host of Democracy Now!, an independent global news program broadcast daily on radio, television and the internet.-Early life:Goodman was born in Bay Shore, New York...

and David Goodman called for the Pulitzer Board to strip Laurence and his paper, The New York Times, of his 1946 Pulitzer Prize. The journalists wrote that at the time Laurence "was also on the payroll of War Department"" and that, after the atomic bombings, he “had a front-page story in the Times disputing the notion that radiation sickness

Radiation Sickness

Radiation Sickness is a VHS by the thrash metal band Nuclear Assault. The video is a recording of a concert at the Hammersmith Odeon, London in 1988. It was released in 1991...

was killing people." They concluded that "his faithful parroting of the government line was crucial in launching a half-century of silence about the deadly lingering effects of the bomb

Effects of nuclear explosions on human health

The medical effects of a nuclear blast upon humans can be put into four categories:*Initial stage -- the first 1–9 weeks, in which are the greatest number of deaths, with 90% due to thermal injury and/or blast effects and 10% due to super-lethal radiation exposure*Intermediate stage -- from 10–12...

”.

Laurence denied that the black rain fallout in Hiroshima was significantly radioactive because it originated from the firestorm that began 30 minutes after explosion, when the radioactive mushroom cloud had been blown many miles downwind.

In their book Hiroshima in America: Fifty Years of Denial from 1995, Robert Jay Lifton and Greg Mitchell wrote, "Here was the nation's leading science reporter, severely compromised, not only unable but disinclined to reveal all he knew about the potential hazards of the most important scientific discovery of his time."

Books by Laurence

- Laurence, William L. Dawn over zero: The story of the atomic bomb. New York: Knopf, 1946.

- ________. We are not helpless: How we can defend ourselves against atomic weapons. New York, 1950.

- ________. The hell bomb. New York: Knopf, 1951.

- ________. Men and atoms: The discovery, the uses, and the future of atomic energy. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1959.

Further reading

- Keever, Beverly Deepe. News Zero: the New York Times and the Bomb. Common Courage Press, 2004. ISBN 1-56751-282-8

- Weart, Spencer. Nuclear Fear: A History of Images. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1988.

External links

- Annotated Bibliography for William L. Laurence from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

- "Informing the Public, August 1945" - Department of EnergyUnited States Department of EnergyThe United States Department of Energy is a Cabinet-level department of the United States government concerned with the United States' policies regarding energy and safety in handling nuclear material...

page which discusses Laurence's role in drafting official press releases - Bio of Laurence at NuclearFiles.org

- "Hiroshima Cover-up: How the War Department's Timesman Won a Pulitzer" - In 2004, Amy GoodmanAmy GoodmanAmy Goodman is an American progressive broadcast journalist, syndicated columnist, investigative reporter and author. Goodman is the host of Democracy Now!, an independent global news program broadcast daily on radio, television and the internet.-Early life:Goodman was born in Bay Shore, New York...

and David Goodman call for the revocation of Laurence’s 1946 Pulitzer Prize. - "Hiroshima Cover-up: Stripping the War Department’s Timesman of His Pulitzer" - Amy Goodman and David Goodman call for the revocation of Laurence’s 1946 Pulitzer Prize on Democracy Now!Democracy Now!Democracy Now! and its staff have received several journalism awards, including the Gracie Award from American Women in Radio & Television; the George Polk Award for its 1998 radio documentary Drilling and Killing: Chevron and Nigeria's Oil Dictatorship, on the Chevron Corporation and the deaths of...

, August 5, 2005 (video, audio, and print transcript).