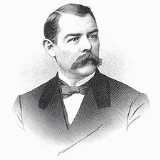

Albion W. Tourgée

Encyclopedia

Albion Winegar Tourgée was an American

soldier, Radical Republican, lawyer, judge, novelist, and diplomat. A pioneer civil rights

activist, he founded the National Citizens' Rights Association and litigated for the plaintiff Homer Plessy

in the famous segregation case Plessy v. Ferguson

(1896). Historian Mark Elliott credits Tourgee with introducing the metaphor of "color-blind

" justice into legal discourse.

on May 2, 1838, the son of farmer Valentine Tourgée and Louisa Emma Winegar. His mother died when he was five. He attended common schools in Ashtabula County

and in Lee, Massachusetts

, where he spent two years living with an uncle. Tourgée entered the University of Rochester

in 1859, but left it in 1861 without attaining a degree to teach school. Upon the outbreak of the Civil War

, in April of the same year he enlisted in the 27th New York Infantry. As was common practice with students who enlisted before completing their studies, the University awarded Tourgée an A.B. degree in June, 1862.

. At the Battle of Perryville

, he was again wounded. On January 21, 1863, Tourgée was captured near Murfreesboro, Tennessee

and was held as a prisoner-of-war in Libby Prison

in Richmond, Virginia

, before his exchange on May 8, 1863. He resumed his duties and fought at the battles of Chickamauga

and Chattanooga. Tourgée resigned his commission on December 6, 1863 and returned to Ohio. He married Emma Doiska Kilbourne, with whom he had one child.

, where he and his wife moved so he could live in a warmer climate better suited to his war injuries. An active participant as a Reconstruction Carpetbagger

in his new home, Tourgée had a number of inspiring and harrowing experiences that gave him ample material and impetus for the writing he would later undertake. In 1868 he represented Guilford County

at the state constitutional convention

, which was dominated by Republicans. There he successfully advocated for equal political and civil rights for all citizens; ending property qualifications for jury duty and officeholding; popular election of all state officers, including judges; free public education; abolition of whipping posts for those convicted of crimes; judicial reform; and uniform taxation. Nevertheless, he discovered that putting these reforms on paper did not translate into an ease of putting them into practice.

As a Republican-installed superior court

judge from 1868 to 1874, Tourgée confronted the increasingly violent Ku Klux Klan

, which was very powerful in his district and repeatedly threatened his life. Among his other activities, he served as a delegate to the 1875 constitutional convention and ran a losing campaign for Congress

in 1878.

Financial success came in 1879 with the publication of A Fool's Errand, by One of the Fools, (Fords, Howard & Hulbert, Nov 1879) a novel based on his experiences of Reconstruction, which sold 200,000 copies. Its sequel, Bricks Without Straw, also was a bestseller

.

In 1881, Tourgée moved to Mayville, New York

, near the Chautauqua Institution

, and made his living as writer and editor of the literary weekly Our Continent until it failed in 1884. He wrote many more novels and essays in the next two decades, many about the Lake Erie

region to which he had located, including, among others, Button's Inn.

Perhaps the nation's most outspoken white Radical on the "race question" in the late 1880s and 1890s, Tourgée had called for resistance to the Louisiana law in his widely read newspaper column, "A Bystander's Notes," which, though written for the Chicago Republican (later known as the Chicago Daily Inter Ocean and after 1872 known as the Chicago Record-Herald), was syndicated in many newspapers across the country. Largely as a consequence of this column, "Judge Tourgée" had become well known in the black press for his bold denunciations of lynching, segregation, disfranchisement, white supremacy, and scientific racism, and he was the New Orleans Citizens' Committee's first choice to lead their legal challenge to the new Louisiana segregation law.

Tourgée, who was lead attorney for Homer Plessy, first deployed the term "color blindness" in his brief

s in the Plessy case and had used it on several prior occasions on behalf of the struggle for civil rights. Indeed, Tourgee's first use of the legal metaphor of "color blindness" came decades before while serving as a Superior Court judge in North Carolina. In his dissent in Plessy, Justice John Marshall Harlan

borrowed the metaphor of "color blindness" from Tourgée’s legal brief.

William McKinley

appointed him U.S. consul

to France, and he lived and served there in Bordeaux until his death, in early 1905, when he became gravely ill for several months, but then appeared to rebound. The recovery was only momentary, however, and he succumbed to acute uremia

resulting from one of his Civil War wounds.

Tourgée's ashes were interred in Mayville, New York, at the Mayville Cemetery and are commemorated by a 12-foot granite obelisk

inscribed thus: I pray thee then Write me as one that loves his fellow-man.

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

soldier, Radical Republican, lawyer, judge, novelist, and diplomat. A pioneer civil rights

Civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from unwarranted infringement by governments and private organizations, and ensure one's ability to participate in the civil and political life of the state without discrimination or repression.Civil rights include...

activist, he founded the National Citizens' Rights Association and litigated for the plaintiff Homer Plessy

Homer Plessy

Homer Plessy was the American plaintiff in the United States Supreme Court decision in Plessy v. Ferguson. Arrested, tried and convicted of a violation of one of Louisiana's racial segregation laws, he appealed through Louisiana state courts to the U.S. Supreme Court, and lost...

in the famous segregation case Plessy v. Ferguson

Plessy v. Ferguson

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 , is a landmark United States Supreme Court decision in the jurisprudence of the United States, upholding the constitutionality of state laws requiring racial segregation in private businesses , under the doctrine of "separate but equal".The decision was handed...

(1896). Historian Mark Elliott credits Tourgee with introducing the metaphor of "color-blind

Race-blind

Color blindness is a sociological term referring to the disregard of racial characteristics when selecting which individuals will participate in some activity or receive some service....

" justice into legal discourse.

Early life

Tourgée was born in rural Williamsfield, OhioWilliamsfield, Ohio

Williamsfield is an unincorporated community in central Williamsfield Township, Ashtabula County, Ohio, United States. Although it is unincorporated, it has a post office, with the ZIP code of 44093. It lies at the intersection of U.S. Route 322 with State Route 7.-References:...

on May 2, 1838, the son of farmer Valentine Tourgée and Louisa Emma Winegar. His mother died when he was five. He attended common schools in Ashtabula County

Ashtabula County, Ohio

Ashtabula County is the northeasternmost county in the state of Ohio. As of 2010, the population was 101,497, its county seat is Jefferson. The county is named for a Native American word meaning "river of many fish"....

and in Lee, Massachusetts

Lee, Massachusetts

Lee is a town in Berkshire County, Massachusetts, United States. It is part of the Pittsfield, Massachusetts, metropolitan statistical area. The population was 5,943 which was determined in the 2010 census. Lee, which includes the villages of South and East Lee, is part of the Berkshires resort...

, where he spent two years living with an uncle. Tourgée entered the University of Rochester

University of Rochester

The University of Rochester is a private, nonsectarian, research university in Rochester, New York, United States. The university grants undergraduate and graduate degrees, including doctoral and professional degrees. The university has six schools and various interdisciplinary programs.The...

in 1859, but left it in 1861 without attaining a degree to teach school. Upon the outbreak of the Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

, in April of the same year he enlisted in the 27th New York Infantry. As was common practice with students who enlisted before completing their studies, the University awarded Tourgée an A.B. degree in June, 1862.

Military service

Tourgée was wounded in the spine at the First Battle of Bull Run, from which he suffered temporary paralysis and a permanent back problem that plagued him for the rest of his life. Upon recovering sufficiently to resume his military career, he was commissioned as a first lieutenant in the 105th Ohio Volunteer Infantry105th Ohio Infantry

The 105th Ohio Volunteer Infantry was an infantry regiment in the Union Army during the American Civil War.-Service:The 105th Ohio Infantry was organized at Cleveland, Ohio and mustered in for three years service on August 20, 1862 under the command of Colonel Albert S. Hall...

. At the Battle of Perryville

Battle of Perryville

The Battle of Perryville, also known as the Battle of Chaplin Hills, was fought on October 8, 1862, in the Chaplin Hills west of Perryville, Kentucky, as the culmination of the Confederate Heartland Offensive during the American Civil War. Confederate Gen. Braxton Bragg's Army of Mississippi won a...

, he was again wounded. On January 21, 1863, Tourgée was captured near Murfreesboro, Tennessee

Murfreesboro, Tennessee

Murfreesboro is a city in and the county seat of Rutherford County, Tennessee, United States. The population was 108,755 according to the United States Census Bureau's 2010 U.S. Census, up from 68,816 residents certified during the 2000 census. The center of population of Tennessee is located in...

and was held as a prisoner-of-war in Libby Prison

Libby Prison

Libby Prison was a Confederate Prison at Richmond, Virginia, during the American Civil War. It gained an infamous reputation for the harsh conditions under which prisoners from the Union Army were kept.- Overview :...

in Richmond, Virginia

Richmond, Virginia

Richmond is the capital of the Commonwealth of Virginia, in the United States. It is an independent city and not part of any county. Richmond is the center of the Richmond Metropolitan Statistical Area and the Greater Richmond area...

, before his exchange on May 8, 1863. He resumed his duties and fought at the battles of Chickamauga

Battle of Chickamauga

The Battle of Chickamauga, fought September 19–20, 1863, marked the end of a Union offensive in southeastern Tennessee and northwestern Georgia called the Chickamauga Campaign...

and Chattanooga. Tourgée resigned his commission on December 6, 1863 and returned to Ohio. He married Emma Doiska Kilbourne, with whom he had one child.

Reconstruction Period

After the war, Tourgée established himself as a lawyer, farmer, and editor in Greensboro, North CarolinaGreensboro, North Carolina

Greensboro is a city in the U.S. state of North Carolina. It is the third-largest city by population in North Carolina and the largest city in Guilford County and the surrounding Piedmont Triad metropolitan region. According to the 2010 U.S...

, where he and his wife moved so he could live in a warmer climate better suited to his war injuries. An active participant as a Reconstruction Carpetbagger

Carpetbagger

Carpetbaggers was a pejorative term Southerners gave to Northerners who moved to the South during the Reconstruction era, between 1865 and 1877....

in his new home, Tourgée had a number of inspiring and harrowing experiences that gave him ample material and impetus for the writing he would later undertake. In 1868 he represented Guilford County

Guilford County, North Carolina

Guilford County is a county located in the U.S. state of North Carolina. In 2010, the Census Bureau estimated the county's population to be 491,230. Its seat is Greensboro. Since 1938, an additional county court has been located in High Point, North Carolina, making Guilford one of only a handful...

at the state constitutional convention

Constitutional convention (political meeting)

A constitutional convention is now a gathering for the purpose of writing a new constitution or revising an existing constitution. A general constitutional convention is called to create the first constitution of a political unit or to entirely replace an existing constitution...

, which was dominated by Republicans. There he successfully advocated for equal political and civil rights for all citizens; ending property qualifications for jury duty and officeholding; popular election of all state officers, including judges; free public education; abolition of whipping posts for those convicted of crimes; judicial reform; and uniform taxation. Nevertheless, he discovered that putting these reforms on paper did not translate into an ease of putting them into practice.

As a Republican-installed superior court

Superior court

In common law systems, a superior court is a court of general competence which typically has unlimited jurisdiction with regard to civil and criminal legal cases...

judge from 1868 to 1874, Tourgée confronted the increasingly violent Ku Klux Klan

Ku Klux Klan

Ku Klux Klan, often abbreviated KKK and informally known as the Klan, is the name of three distinct past and present far-right organizations in the United States, which have advocated extremist reactionary currents such as white supremacy, white nationalism, and anti-immigration, historically...

, which was very powerful in his district and repeatedly threatened his life. Among his other activities, he served as a delegate to the 1875 constitutional convention and ran a losing campaign for Congress

United States Congress

The United States Congress is the bicameral legislature of the federal government of the United States, consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Congress meets in the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C....

in 1878.

Literary Life

Albion's first literary endeavor was the novel Toinette, written while living in North Carolina between 1868 and 1869. It was not published until 1874 under the pseudonym "Henry Churton"; it was renamed A Royal Gentleman when it was republished in 1881.Financial success came in 1879 with the publication of A Fool's Errand, by One of the Fools, (Fords, Howard & Hulbert, Nov 1879) a novel based on his experiences of Reconstruction, which sold 200,000 copies. Its sequel, Bricks Without Straw, also was a bestseller

Bestseller

A bestseller is a book that is identified as extremely popular by its inclusion on lists of currently top selling titles that are based on publishing industry and book trade figures and published by newspapers, magazines, or bookstore chains. Some lists are broken down into classifications and...

.

In 1881, Tourgée moved to Mayville, New York

Mayville, New York

-Demographics:As of the census of 2000, there were 1,756 people, 686 households, and 399 families residing in the village. The population density was 875.0 people per square mile . There were 860 housing units at an average density of 428.5 per square mile...

, near the Chautauqua Institution

Chautauqua Institution

The Chautauqua Institution is a non-profit adult education center and summer resort located on 750 acres in Chautauqua, New York, 17 miles northwest of Jamestown in the western part of New York State...

, and made his living as writer and editor of the literary weekly Our Continent until it failed in 1884. He wrote many more novels and essays in the next two decades, many about the Lake Erie

Lake Erie

Lake Erie is the fourth largest lake of the five Great Lakes in North America, and the tenth largest globally. It is the southernmost, shallowest, and smallest by volume of the Great Lakes and therefore also has the shortest average water residence time. It is bounded on the north by the...

region to which he had located, including, among others, Button's Inn.

Plessy Case

What would become the Plessy case began when a group of prominent black leaders in New Orleans organized a "Citizens' Committee" in September 1891 to challenge Louisiana's 1890 law intended "to promote the comfort of passengers" by requiring all state railway companies "to provide equal but separate accommodations for the white and colored races, by providing separate coaches or compartments" on their passenger trains. To assist them in their challenge, this group retained the legal services of "Judge Tourgée," as he was popularly known.Perhaps the nation's most outspoken white Radical on the "race question" in the late 1880s and 1890s, Tourgée had called for resistance to the Louisiana law in his widely read newspaper column, "A Bystander's Notes," which, though written for the Chicago Republican (later known as the Chicago Daily Inter Ocean and after 1872 known as the Chicago Record-Herald), was syndicated in many newspapers across the country. Largely as a consequence of this column, "Judge Tourgée" had become well known in the black press for his bold denunciations of lynching, segregation, disfranchisement, white supremacy, and scientific racism, and he was the New Orleans Citizens' Committee's first choice to lead their legal challenge to the new Louisiana segregation law.

Tourgée, who was lead attorney for Homer Plessy, first deployed the term "color blindness" in his brief

Brief (law)

A brief is a written legal document used in various legal adversarial systems that is presented to a court arguing why the party to the case should prevail....

s in the Plessy case and had used it on several prior occasions on behalf of the struggle for civil rights. Indeed, Tourgee's first use of the legal metaphor of "color blindness" came decades before while serving as a Superior Court judge in North Carolina. In his dissent in Plessy, Justice John Marshall Harlan

John Marshall Harlan

John Marshall Harlan was a Kentucky lawyer and politician who served as an associate justice on the Supreme Court. He is most notable as the lone dissenter in the Civil Rights Cases , and Plessy v...

borrowed the metaphor of "color blindness" from Tourgée’s legal brief.

Later life

In 1897, following Tourgée's involvement in the Plessy case, PresidentPresident of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

William McKinley

William McKinley

William McKinley, Jr. was the 25th President of the United States . He is best known for winning fiercely fought elections, while supporting the gold standard and high tariffs; he succeeded in forging a Republican coalition that for the most part dominated national politics until the 1930s...

appointed him U.S. consul

Consul (representative)

The political title Consul is used for the official representatives of the government of one state in the territory of another, normally acting to assist and protect the citizens of the consul's own country, and to facilitate trade and friendship between the peoples of the two countries...

to France, and he lived and served there in Bordeaux until his death, in early 1905, when he became gravely ill for several months, but then appeared to rebound. The recovery was only momentary, however, and he succumbed to acute uremia

Uremia

Uremia or uraemia is a term used to loosely describe the illness accompanying kidney failure , in particular the nitrogenous waste products associated with the failure of this organ....

resulting from one of his Civil War wounds.

Tourgée's ashes were interred in Mayville, New York, at the Mayville Cemetery and are commemorated by a 12-foot granite obelisk

Obelisk

An obelisk is a tall, four-sided, narrow tapering monument which ends in a pyramid-like shape at the top, and is said to resemble a petrified ray of the sun-disk. A pair of obelisks usually stood in front of a pylon...

inscribed thus: I pray thee then Write me as one that loves his fellow-man.