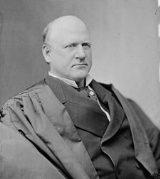

John Marshall Harlan

Encyclopedia

John Marshall Harlan was a Kentucky

lawyer

and politician who served as an associate justice

on the Supreme Court

. He is most notable as the lone dissenter

in the Civil Rights Cases

(1883), and Plessy v. Ferguson

(1896), which, respectively, struck down as unconstitutional federal anti-discrimination legislation and upheld Southern segregation statutes. In Pace v. Alabama

(1883) he supported opinion that anti-miscegenation laws

are constitutional.

, a lawyer and politician; his mother, Elizabeth, née Davenport, was the daughter of a pioneer from Virginia. After attending school in Frankfort

, Harlan enrolled at Centre College

, where he was a member of Beta Theta Pi

and graduated with honors. Though his mother wanted Harlan to become a merchant, James insisted that his son follow him into the legal profession, and Harlan joined his father's law practice in 1852. Yet while James Harlan could have trained his son in the office as was the norm in that era, he sent John to attend law school at Transylvania University

in 1853, where George Robertson

and Thomas Alexander Marshall

were among his instructors.

A member of the Whig Party

like his father, Harlan got an early start in politics when, in 1851, he was offered the post of adjutant general

of the state by the governor at that time, John L. Helm

. He served in the post for the next eight years, which gave him a statewide presence and familiarized him with many of Kentucky's leading political figures. With the Whig Party's dissolution in the early 1850s, he shifted his affiliation to the Know Nothings, despite his discomfort with their opposition to Catholicism. Harlan's personal popularity within the state was such that he was able to survive the decline of the Know Nothing movement in the late 1850s, winning election as the county judge for Franklin County, Kentucky

in 1858. The following year, he renounced his allegiance to the Know Nothings and joined the state's Opposition Party

, serving as their candidate in an unsuccessful attempt to defeat William E. Simms

for the seat in Kentucky's 8th congressional district

.

During the 1860 presidential election

, Harlan supported the Constitutional Union

candidate, John Bell

. In the secession crisis that followed Abraham Lincoln

's victory, Harlan sought to prevent Kentucky from seceding. When the state legislature voted to create a new militia Harlan organized and led a company of zouave

s before recruiting a company that was mustered into the service as the 10th Kentucky Infantry

. Harlan served in the Western theater

until the death of his father James in February 1863, whereupon Harlan resigned his commission as colonel

and returned to Frankfort in order to support his family.

Three weeks after leaving the army, Harlan was nominated by the Union Party as their nominee to become the Attorney General of Kentucky

. Campaigning on a platform of vigorous prosecution of the war, he won the election by a considerable margin. As attorney general for the state, Harlan issued legal opinions and advocated for the state in a number of court cases. Party politics, however, occupied much of his time; Harlan campaigned for Democrat George McClellan

in the 1864 presidential election

and worked as a junior partner to the state Democratic party in the aftermath of the Civil War. After losing a bid for reelection as attorney general, Harlan joined the Republican Party in 1868.

Moving to Louisville

, Harlan formed a partnership with John E. Newman, a former circuit court judge and, like Harlan, a Unionist turned Republican. There their firm prospered, and they took in a new partner, Benjamin Bristow

, in 1870. In addition to his legal practice, Harlan worked to build up the Republican Party organization in the state, and ran unsuccessfully as the party's nominee for governor of Kentucky

in both 1871 and 1875. Despite his defeats, he earned a reputation as a campaign speaker and Republican activist. In the 1876 presidential election

, Harlan worked to nominate Bristow as the Republican party's nominee, though when Rutherford B. Hayes

emerged as the compromise candidate, Harlan switched his delegation's votes and subsequently campaigned on Hayes's behalf.

, initially the only job Harlan was offered was as a member of a commission sent to Louisiana to resolve disputed statewide elections there. Justice David Davis

, however, had resigned from the Supreme Court in January 1877 after being selected as a United States Senator

by the Illinois General Assembly

. Seeking a replacement, Hayes settled on Harlan, and formally submitted his name to the Senate on October 16. Though Harlan's nomination prompted some criticism from Republican stalwarts, he was confirmed unanimously on November 29, 1877.

.

When Harlan began his service the Supreme Court faced a heavy workload that consisted primarily of diversity

and removal

cases, with constitutional issues rare. Justices also rode circuit

in the various federal judicial circuits; though these usually corresponded to the region from which the justice was appointed, Harlan was assigned the Seventh Circuit

due to his junior status. Harlan rode the Seventh Circuit until 1896, when he switched to his home circuit, the Sixth

, upon the death of its previous holder, Justice Howell Edmunds Jackson

.

(1883), the Supreme Court struck down the Civil Rights Act of 1875, holding that the act exceeded Congressional powers. Harlan alone dissented, vigorously, charging that the majority had subverted the Reconstruction Amendments: "The substance and spirit of the recent amendments of the constitution have been sacrificed by a subtle and ingenious verbal criticism." Harlan also dissented in Giles v. Harris

(1903), a case challenging the use of grandfather clauses to restrict voting rolls and de facto exclude blacks.

Harlan did not embrace the idea of full social racial equality. In his Plessy dissent, Harlan wrote that

Harlan was also viewed by some as opposition toward other races, such as Chinese. In 1898 Harlan joined Chief Justice Fuller's dissent in United States v. Wong Kim Ark

, dissenting from the Court's holding that persons of Chinese descent born in the United States were citizens by birth. Fuller and Harlan argued that the principle of jus sanguinis (that is, the concept of a child inheriting his or her father's citizenship by descent regardless of birthplace) had been more pervasive in U.S. legal history since independence. In the view of the minority, excessive reliance on jus soli (birthplace) as the principal determiner of citizenship would lead to an untenable state of affairs in which "the children of foreigners, happening to be born to them while passing through the country, whether of royal parentage or not, or whether of the Mongolian, Malay or other race, were eligible to the presidency, while children of our citizens, born abroad, were not". It is alleged they denounced

Harlan was the first justice to argue that the Fourteenth Amendment

incorporated

the Bill of Rights (making rights guarantees applicable to the individual states), in Hurtado v. California

(1884). His argument was later adopted by Hugo Black

. Today, most of the protections of the Bill of Rights and Civil War amendments incorporated, though not by the theory advanced by Harlan.

Harlan was also the most stridently anti-imperialist justice on the Supreme Court, arguing consistently in the Insular Cases

that the Constitution did not permit the demarcation of different rights between citizens of the states and the residents of newly acquired territories in the Philippines

, Hawaii

, Guam

and Puerto Rico

, a view that was consistently in the minority. In Hawaii v. Mankichi (1903) his opinion stated: "If the principles now announced should become firmly established, the time may not be far distant when, under the exactions of trade and commerce, and to gratify an ambition to become the dominant power in all the earth, the United States will acquire territories in every direction... whose inhabitants will be regarded as 'subjects' or 'dependent peoples,' to be controlled as Congress may see fit... which will engraft on our republican institutions a colonial system entirely foreign to the genius of our Government and abhorrent to the principles that underlie and pervade our Constitution."

Harlan's partial dissent in the 1911 Standard Oil anti-trust decision (Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey v. United States,221 U.S. 1) penetratingly addressed issues of statutory construction reaching beyond the Sherman Anti-Trust Act itself.

Harlan dissented in Lochner v. New York

, though he agreed with the majority "that there is a liberty of contract which cannot be violated even under the sanction of direct legislative enactment."

(1896), which established the doctrine of "separate but equal

" as it legitimized both Southern and Northern segregation practices. The Court, speaking through Justice Henry B. Brown, held that separation of the races was not inherently unequal, and any inferiority felt by blacks at having to use separate facilities was an illusion: "We consider the underlying fallacy of the plaintiff's argument to consist in the assumption that the enforced separation of the two races stamps the colored race with a badge of inferiority. If this be so, it is not by reason of any-thing found in the act, but solely because the colored race chooses to put that construction upon it." (While the Court held that separate facilities had to be equal, in practice the facilities designated for blacks were invariably inferior.)

Alone in dissent, Harlan argued that the Louisiana law at issue, which forced separation of white and black passengers on railway cars, was a "badge of servitude" that degraded African-Americans, and claimed that the Court's ruling would become as infamous as its ruling in the Dred Scott case

.

He wrote:

from 1901 until 1906. Their second son, James S. Harlan

, practiced in Chicago and served as attorney general of Puerto Rico before being appointed to the Interstate Commerce Commission

in 1906 and becoming that body's chairman in 1914. Their youngest son, John Maynard, also practiced in Chicago and served as an alderman

before running unsuccessfully for mayor in both 1897 and 1905; John Maynard's son, John Marshall Harlan II

, served as a Supreme Court Associate Justice from 1955 until 1971.

It is also said that Harlan's attitudes towards civil rights were influenced by the social principles of the Presbyterian Church

. During his tenure as a Justice, he taught a Sunday school class at a Presbyterian church in Washington, DC.

, Washington, D.C. where his body resides along with those of three other justices.

There are collections of Harlan's papers at the University of Louisville

in Louisville, Kentucky

, and at the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress

in Washington, D.C.

. Both are open for research. Other papers are collected at many other libraries.

Named for Justice Harlan, the "Harlan Scholars" of the University of Louisville

/Louis D. Brandeis School of Law

, is an undergraduate organization for students interested in attending law school

.

Centre College, Harlan's alma mater, instituted the John Marshall Harlan Professorship in Government in 1994 in honor of Harlan's reputation as one of the Supreme Court's greatest justices.

In 2009, with the 200th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln's birth coinciding with the election of the first black American president, Harlan's views on civil rights - far ahead of his time - were celebrated and remembered by many.

Kentucky

The Commonwealth of Kentucky is a state located in the East Central United States of America. As classified by the United States Census Bureau, Kentucky is a Southern state, more specifically in the East South Central region. Kentucky is one of four U.S. states constituted as a commonwealth...

lawyer

Lawyer

A lawyer, according to Black's Law Dictionary, is "a person learned in the law; as an attorney, counsel or solicitor; a person who is practicing law." Law is the system of rules of conduct established by the sovereign government of a society to correct wrongs, maintain the stability of political...

and politician who served as an associate justice

Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States

Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States are the members of the Supreme Court of the United States other than the Chief Justice of the United States...

on the Supreme Court

Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States is the highest court in the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all state and federal courts, and original jurisdiction over a small range of cases...

. He is most notable as the lone dissenter

Dissenter

The term dissenter , labels one who disagrees in matters of opinion, belief, etc. In the social and religious history of England and Wales, however, it refers particularly to a member of a religious body who has, for one reason or another, separated from the Established Church.Originally, the term...

in the Civil Rights Cases

Civil Rights Cases

The Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 , were a group of five similar cases consolidated into one issue for the United States Supreme Court to review...

(1883), and Plessy v. Ferguson

Plessy v. Ferguson

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 , is a landmark United States Supreme Court decision in the jurisprudence of the United States, upholding the constitutionality of state laws requiring racial segregation in private businesses , under the doctrine of "separate but equal".The decision was handed...

(1896), which, respectively, struck down as unconstitutional federal anti-discrimination legislation and upheld Southern segregation statutes. In Pace v. Alabama

Pace v. Alabama

Pace v. Alabama, 106 U.S. 583 , was a case in which the United States Supreme Court affirmed that Alabama's anti-miscegenation statute was constitutional. This ruling was overturned by the Supreme Court in 1964 in McLaughlin v. Florida and in 1967 in Loving v...

(1883) he supported opinion that anti-miscegenation laws

Anti-miscegenation laws

Anti-miscegenation laws, also known as miscegenation laws, were laws that enforced racial segregation at the level of marriage and intimate relationships by criminalizing interracial marriage and sometimes also sex between members of different races...

are constitutional.

Early life and political career

Harlan was born into a prominent Kentucky slaveholding family whose presence in the region dated back to 1779. Harlan's father was James HarlanJames Harlan (congressman)

James Harlan was a U.S. Representative from Kentucky.Born in Mercer County, Kentucky, Harlan attended school before working as a clerk in a dry goods store from 1817 to 1821. Deciding to embark upon a legal career, he read law under the guidance of a local judge before gaining admission to the bar...

, a lawyer and politician; his mother, Elizabeth, née Davenport, was the daughter of a pioneer from Virginia. After attending school in Frankfort

Frankfort, Kentucky

Frankfort is a city in Kentucky that serves as the state capital and the county seat of Franklin County. The population was 27,741 at the 2000 census; by population it is the 5th smallest state capital in the United States...

, Harlan enrolled at Centre College

Centre College

Centre College is a private liberal arts college in Danville, Kentucky, USA, a community of approximately 16,000 in Boyle County south of Lexington, KY. Centre is an exclusively undergraduate four-year institution. Centre was founded by Presbyterian leaders, with whom it maintains a loose...

, where he was a member of Beta Theta Pi

Beta Theta Pi

Beta Theta Pi , often just called Beta, is a social collegiate fraternity that was founded in 1839 at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, USA, where it is part of the Miami Triad which includes Phi Delta Theta and Sigma Chi. It has over 138 active chapters and colonies in the United States and Canada...

and graduated with honors. Though his mother wanted Harlan to become a merchant, James insisted that his son follow him into the legal profession, and Harlan joined his father's law practice in 1852. Yet while James Harlan could have trained his son in the office as was the norm in that era, he sent John to attend law school at Transylvania University

Transylvania University

Transylvania University is a private, undergraduate liberal arts college in Lexington, Kentucky, United States, affiliated with the Christian Church . The school was founded in 1780. It offers 38 majors, and pre-professional degrees in engineering and accounting...

in 1853, where George Robertson

George Robertson (congressman)

George Robertson was a U.S. Representative from Kentucky.-Early life:Born near Harrodsburg, Kentucky, Robertson pursued preparatory studies and attended Transylvania University, Lexington, Kentucky, until 1806...

and Thomas Alexander Marshall

Thomas Alexander Marshall

Thomas Alexander Marshall was a U.S. Representative from Kentucky, son of Humphrey Marshall .Born near Versailles, Kentucky, Marshall pursued preparatory studies.He was graduated from Yale College in 1815....

were among his instructors.

A member of the Whig Party

Whig Party (United States)

The Whig Party was a political party of the United States during the era of Jacksonian democracy. Considered integral to the Second Party System and operating from the early 1830s to the mid-1850s, the party was formed in opposition to the policies of President Andrew Jackson and his Democratic...

like his father, Harlan got an early start in politics when, in 1851, he was offered the post of adjutant general

Adjutant general

An Adjutant General is a military chief administrative officer.-Imperial Russia:In Imperial Russia, the General-Adjutant was a Court officer, who was usually an army general. He served as a personal aide to the Tsar and hence was a member of the H. I. M. Retinue...

of the state by the governor at that time, John L. Helm

John L. Helm

John LaRue Helm was the 18th and 24th governor of the U.S. state of Kentucky, although his service in that office totaled less than fourteen months. He also represented Hardin County in both houses of the Kentucky General Assembly and was chosen to be the Speaker of the Kentucky House of...

. He served in the post for the next eight years, which gave him a statewide presence and familiarized him with many of Kentucky's leading political figures. With the Whig Party's dissolution in the early 1850s, he shifted his affiliation to the Know Nothings, despite his discomfort with their opposition to Catholicism. Harlan's personal popularity within the state was such that he was able to survive the decline of the Know Nothing movement in the late 1850s, winning election as the county judge for Franklin County, Kentucky

Franklin County, Kentucky

As of the census of 2000, there were 47,687 people, 19,907 households, and 12,840 families residing in the county. The population density was . There were 21,409 housing units at an average density of...

in 1858. The following year, he renounced his allegiance to the Know Nothings and joined the state's Opposition Party

Opposition Party (United States)

The Opposition Party in the United States is a label with two different applications in Congressional history, as a majority party in Congress 1854-58, and as a Third Party in the South 1858-1860....

, serving as their candidate in an unsuccessful attempt to defeat William E. Simms

William E. Simms

William Emmett Simms was a U.S. Representative from Kentucky. He also served as a commissioner for the Confederate government of Kentucky and in several posts in the Confederate States government during the American Civil War.-Biography:Simms was born near Cynthiana, Harrison County, Kentucky...

for the seat in Kentucky's 8th congressional district

Kentucky's 8th congressional district

United States House of Representatives, Kentucky District 8 was a district of the United States Congress in Kentucky. It was lost to redistricting in 1963. Its last Representative was Eugene Siler.-List of representatives:-References:*...

.

During the 1860 presidential election

United States presidential election, 1860

The United States presidential election of 1860 was a quadrennial election, held on November 6, 1860, for the office of President of the United States and the immediate impetus for the outbreak of the American Civil War. The nation had been divided throughout the 1850s on questions surrounding the...

, Harlan supported the Constitutional Union

Constitutional Union Party (United States)

The Constitutional Union Party was a political party in the United States created in 1860. It was made up of conservative former Whigs who wanted to avoid disunion over the slavery issue...

candidate, John Bell

John Bell (Tennessee politician)

John Bell was a U.S. politician, attorney, and plantation owner. A wealthy slaveholder from Tennessee, Bell served in the United States Congress in both the House of Representatives and Senate. He began his career as a Democrat, he eventually fell out with Andrew Jackson and became a Whig...

. In the secession crisis that followed Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln was the 16th President of the United States, serving from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. He successfully led his country through a great constitutional, military and moral crisis – the American Civil War – preserving the Union, while ending slavery, and...

's victory, Harlan sought to prevent Kentucky from seceding. When the state legislature voted to create a new militia Harlan organized and led a company of zouave

Zouave

Zouave was the title given to certain light infantry regiments in the French Army, normally serving in French North Africa between 1831 and 1962. The name was also adopted during the 19th century by units in other armies, especially volunteer regiments raised for service in the American Civil War...

s before recruiting a company that was mustered into the service as the 10th Kentucky Infantry

10th Regiment Kentucky Volunteer Infantry

The 10th Kentucky Volunteer Infantry Regiment was an infantry regiment that served in the Union Army during the American Civil War.-Service:The 10th Kentucky Infantry was organized at Lebanon, Kentucky and mustered in for a three year enlistment on November 21, 1861.The regiment was attached to 2nd...

. Harlan served in the Western theater

Western Theater of the American Civil War

This article presents an overview of major military and naval operations in the Western Theater of the American Civil War.-Theater of operations:...

until the death of his father James in February 1863, whereupon Harlan resigned his commission as colonel

Colonel (United States)

In the United States Army, Air Force, and Marine Corps, colonel is a senior field grade military officer rank just above the rank of lieutenant colonel and just below the rank of brigadier general...

and returned to Frankfort in order to support his family.

Three weeks after leaving the army, Harlan was nominated by the Union Party as their nominee to become the Attorney General of Kentucky

Attorney General of Kentucky

The Attorney General of Kentucky is an office created by the Kentucky Constitution. . Under Kentucky law, he serves several roles, including the state's chief prosecutor , the state's chief law enforcement officer , and the state's chief law officer...

. Campaigning on a platform of vigorous prosecution of the war, he won the election by a considerable margin. As attorney general for the state, Harlan issued legal opinions and advocated for the state in a number of court cases. Party politics, however, occupied much of his time; Harlan campaigned for Democrat George McClellan

George B. McClellan

George Brinton McClellan was a major general during the American Civil War. He organized the famous Army of the Potomac and served briefly as the general-in-chief of the Union Army. Early in the war, McClellan played an important role in raising a well-trained and organized army for the Union...

in the 1864 presidential election

United States presidential election, 1864

In the United States Presidential election of 1864, Abraham Lincoln was re-elected as president. The election was held during the Civil War. Lincoln ran under the National Union ticket against Democratic candidate George B. McClellan, his former top general. McClellan ran as the "peace candidate",...

and worked as a junior partner to the state Democratic party in the aftermath of the Civil War. After losing a bid for reelection as attorney general, Harlan joined the Republican Party in 1868.

Moving to Louisville

Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville is the largest city in the U.S. state of Kentucky, and the county seat of Jefferson County. Since 2003, the city's borders have been coterminous with those of the county because of a city-county merger. The city's population at the 2010 census was 741,096...

, Harlan formed a partnership with John E. Newman, a former circuit court judge and, like Harlan, a Unionist turned Republican. There their firm prospered, and they took in a new partner, Benjamin Bristow

Benjamin Bristow

Benjamin Helm Bristow was an American lawyer and Republican Party politician who served as the first Solicitor General of the United States and as a U.S. Treasury Secretary. Fighting for the Union, Bristow served in the army during the American Civil War and was promoted to Colonel...

, in 1870. In addition to his legal practice, Harlan worked to build up the Republican Party organization in the state, and ran unsuccessfully as the party's nominee for governor of Kentucky

Governor of Kentucky

The Governor of the Commonwealth of Kentucky is the head of the executive branch of government in the U.S. state of Kentucky. Fifty-six men and one woman have served as Governor of Kentucky. The governor's term is four years in length; since 1992, incumbents have been able to seek re-election once...

in both 1871 and 1875. Despite his defeats, he earned a reputation as a campaign speaker and Republican activist. In the 1876 presidential election

United States presidential election, 1876

The United States presidential election of 1876 was one of the most disputed and controversial presidential elections in American history. Samuel J. Tilden of New York outpolled Ohio's Rutherford B. Hayes in the popular vote, and had 184 electoral votes to Hayes's 165, with 20 votes uncounted...

, Harlan worked to nominate Bristow as the Republican party's nominee, though when Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes was the 19th President of the United States . As president, he oversaw the end of Reconstruction and the United States' entry into the Second Industrial Revolution...

emerged as the compromise candidate, Harlan switched his delegation's votes and subsequently campaigned on Hayes's behalf.

Nomination

Though considered for a number of positions in the new administration, most notably for Attorney GeneralUnited States Attorney General

The United States Attorney General is the head of the United States Department of Justice concerned with legal affairs and is the chief law enforcement officer of the United States government. The attorney general is considered to be the chief lawyer of the U.S. government...

, initially the only job Harlan was offered was as a member of a commission sent to Louisiana to resolve disputed statewide elections there. Justice David Davis

David Davis (Supreme Court justice)

David Davis was a United States Senator from Illinois and associate justice of the United States Supreme Court. He also served as Abraham Lincoln's campaign manager at the 1860 Republican National Convention....

, however, had resigned from the Supreme Court in January 1877 after being selected as a United States Senator

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

by the Illinois General Assembly

Illinois General Assembly

The Illinois General Assembly is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Illinois and comprises the Illinois House of Representatives and the Illinois Senate. The General Assembly was created by the first state constitution adopted in 1818. Illinois has 59 legislative districts, with two...

. Seeking a replacement, Hayes settled on Harlan, and formally submitted his name to the Senate on October 16. Though Harlan's nomination prompted some criticism from Republican stalwarts, he was confirmed unanimously on November 29, 1877.

Life on the Court

Harlan greatly enjoyed his time as a justice, which would last for the remainder of his life. From the start he established good relationships with his fellow justices, and was close friends with a number of them. Yet money problems continually plagued him, particularly as he began to put his three sons through college. Debt was a constant concern, and in the early 1880s he considered resigning from the Court and returning to private practice. Though he ultimately elected to remain on the Court, Harlan supplemented his income by teaching constitutional law at the Columbian Law School, which later became the law school of George Washington UniversityGeorge Washington University

The George Washington University is a private, coeducational comprehensive university located in Washington, D.C. in the United States...

.

When Harlan began his service the Supreme Court faced a heavy workload that consisted primarily of diversity

Diversity jurisdiction

In the law of the United States, diversity jurisdiction is a form of subject-matter jurisdiction in civil procedure in which a United States district court has the power to hear a civil case where the persons that are parties are "diverse" in citizenship, which generally indicates that they are...

and removal

Removal jurisdiction

In the United States, removal jurisdiction refers to the right of a defendant to move a lawsuit filed in state court to the federal district court for the federal judicial district in which the state court sits. This is a general exception to the usual American rule giving the plaintiff the right...

cases, with constitutional issues rare. Justices also rode circuit

Circuit rider (U.S. Court system)

Circuit rider is a term in the United States for a professional who travels a regular circuit of locations to provide services. The term first came into widespread application for judges, particularly in the sparsely populated American West, who would hold court in each town in their circuit on a...

in the various federal judicial circuits; though these usually corresponded to the region from which the justice was appointed, Harlan was assigned the Seventh Circuit

United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit

The United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit is a federal court with appellate jurisdiction over the courts in the following districts:* Central District of Illinois* Northern District of Illinois...

due to his junior status. Harlan rode the Seventh Circuit until 1896, when he switched to his home circuit, the Sixth

United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

The United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit is a federal court with appellate jurisdiction over the district courts in the following districts:* Eastern District of Kentucky* Western District of Kentucky...

, upon the death of its previous holder, Justice Howell Edmunds Jackson

Howell Edmunds Jackson

Howell Edmunds Jackson was an American jurist and politician. He served on the United States Supreme Court, in the U.S. Senate, United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, and the Tennessee House of Representatives. He authored notable opinions on the Interstate Commerce Act and the...

.

Jurisprudence

As the Court moved away from interpreting the Reconstruction Amendments to protect Black Americans, Harlan wrote several eloquent dissents in support of equal rights for Black Americans and racial equality. In the Civil Rights CasesCivil Rights Cases

The Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 , were a group of five similar cases consolidated into one issue for the United States Supreme Court to review...

(1883), the Supreme Court struck down the Civil Rights Act of 1875, holding that the act exceeded Congressional powers. Harlan alone dissented, vigorously, charging that the majority had subverted the Reconstruction Amendments: "The substance and spirit of the recent amendments of the constitution have been sacrificed by a subtle and ingenious verbal criticism." Harlan also dissented in Giles v. Harris

Giles v. Harris

Giles v. Harris, 189 U.S. 475 , was an early 20th century United States Supreme Court case in which the Court upheld a state constitution's requirements for voter registration and qualifications...

(1903), a case challenging the use of grandfather clauses to restrict voting rolls and de facto exclude blacks.

Harlan did not embrace the idea of full social racial equality. In his Plessy dissent, Harlan wrote that

[T]he white race deems itself to be the dominant race in this country. And so it is, in prestige, in achievements, in education, in wealth and in power. So, I doubt not, it will continue to be for all time, if it remains true to its great heritage and holds fast to the principles of constitutional liberty. But in view of the constitution, in the eye of the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens. There is no caste here. Our constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law.

Harlan was also viewed by some as opposition toward other races, such as Chinese. In 1898 Harlan joined Chief Justice Fuller's dissent in United States v. Wong Kim Ark

United States v. Wong Kim Ark

United States v. Wong Kim Ark, , was a United States Supreme Court decision that set an important legal precedent about the role of jus soli as a factor in determining a person's claim to United States citizenship...

, dissenting from the Court's holding that persons of Chinese descent born in the United States were citizens by birth. Fuller and Harlan argued that the principle of jus sanguinis (that is, the concept of a child inheriting his or her father's citizenship by descent regardless of birthplace) had been more pervasive in U.S. legal history since independence. In the view of the minority, excessive reliance on jus soli (birthplace) as the principal determiner of citizenship would lead to an untenable state of affairs in which "the children of foreigners, happening to be born to them while passing through the country, whether of royal parentage or not, or whether of the Mongolian, Malay or other race, were eligible to the presidency, while children of our citizens, born abroad, were not". It is alleged they denounced

the presence within our territory of large numbers of Chinese laborers, of a distinct race and religion, remaining strangers in the land, residing apart by themselves, tenaciously adhering to the customs and usage of their own country, unfamiliar with our institutions and religion, and apparently incapable of assimilating with our people.

Harlan was the first justice to argue that the Fourteenth Amendment

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was adopted on July 9, 1868, as one of the Reconstruction Amendments.Its Citizenship Clause provides a broad definition of citizenship that overruled the Dred Scott v...

incorporated

Incorporation (Bill of Rights)

The incorporation of the Bill of Rights is the process by which American courts have applied portions of the U.S. Bill of Rights to the states. Prior to the 1890s, the Bill of Rights was held only to apply to the federal government...

the Bill of Rights (making rights guarantees applicable to the individual states), in Hurtado v. California

Hurtado v. California

Hurtado v. California, 110 U.S. 516 , was a case decided on by the United States Supreme Court. The case helped define rules regarding the use of grand juries in indictments.- Facts of the case :...

(1884). His argument was later adopted by Hugo Black

Hugo Black

Hugo Lafayette Black was an American politician and jurist. A member of the Democratic Party, Black represented Alabama in the United States Senate from 1927 to 1937, and served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1937 to 1971. Black was nominated to the Supreme...

. Today, most of the protections of the Bill of Rights and Civil War amendments incorporated, though not by the theory advanced by Harlan.

Harlan was also the most stridently anti-imperialist justice on the Supreme Court, arguing consistently in the Insular Cases

Insular Cases

The Insular Cases are several U.S. Supreme Court cases concerning the status of territories acquired by the U.S. in the Spanish-American War . The name "insular" derives from the fact that these territories are islands and were administered by the War Department's Bureau of Insular Affairs...

that the Constitution did not permit the demarcation of different rights between citizens of the states and the residents of newly acquired territories in the Philippines

Philippines

The Philippines , officially known as the Republic of the Philippines , is a country in Southeast Asia in the western Pacific Ocean. To its north across the Luzon Strait lies Taiwan. West across the South China Sea sits Vietnam...

, Hawaii

Hawaii

Hawaii is the newest of the 50 U.S. states , and is the only U.S. state made up entirely of islands. It is the northernmost island group in Polynesia, occupying most of an archipelago in the central Pacific Ocean, southwest of the continental United States, southeast of Japan, and northeast of...

, Guam

Guam

Guam is an organized, unincorporated territory of the United States located in the western Pacific Ocean. It is one of five U.S. territories with an established civilian government. Guam is listed as one of 16 Non-Self-Governing Territories by the Special Committee on Decolonization of the United...

and Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico , officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico , is an unincorporated territory of the United States, located in the northeastern Caribbean, east of the Dominican Republic and west of both the United States Virgin Islands and the British Virgin Islands.Puerto Rico comprises an...

, a view that was consistently in the minority. In Hawaii v. Mankichi (1903) his opinion stated: "If the principles now announced should become firmly established, the time may not be far distant when, under the exactions of trade and commerce, and to gratify an ambition to become the dominant power in all the earth, the United States will acquire territories in every direction... whose inhabitants will be regarded as 'subjects' or 'dependent peoples,' to be controlled as Congress may see fit... which will engraft on our republican institutions a colonial system entirely foreign to the genius of our Government and abhorrent to the principles that underlie and pervade our Constitution."

Harlan's partial dissent in the 1911 Standard Oil anti-trust decision (Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey v. United States,221 U.S. 1) penetratingly addressed issues of statutory construction reaching beyond the Sherman Anti-Trust Act itself.

Harlan dissented in Lochner v. New York

Lochner v. New York

Lochner vs. New York, , was a landmark United States Supreme Court case that held a "liberty of contract" was implicit in the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The case involved a New York law that limited the number of hours that a baker could work each day to ten, and limited the...

, though he agreed with the majority "that there is a liberty of contract which cannot be violated even under the sanction of direct legislative enactment."

Plessy v. Ferguson (1896)

In 1896, the Supreme Court handed down one of the most famous decisions in U.S. history, Plessy v. FergusonPlessy v. Ferguson

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 , is a landmark United States Supreme Court decision in the jurisprudence of the United States, upholding the constitutionality of state laws requiring racial segregation in private businesses , under the doctrine of "separate but equal".The decision was handed...

(1896), which established the doctrine of "separate but equal

Separate but equal

Separate but equal was a legal doctrine in United States constitutional law that justified systems of segregation. Under this doctrine, services, facilities and public accommodations were allowed to be separated by race, on the condition that the quality of each group's public facilities was to...

" as it legitimized both Southern and Northern segregation practices. The Court, speaking through Justice Henry B. Brown, held that separation of the races was not inherently unequal, and any inferiority felt by blacks at having to use separate facilities was an illusion: "We consider the underlying fallacy of the plaintiff's argument to consist in the assumption that the enforced separation of the two races stamps the colored race with a badge of inferiority. If this be so, it is not by reason of any-thing found in the act, but solely because the colored race chooses to put that construction upon it." (While the Court held that separate facilities had to be equal, in practice the facilities designated for blacks were invariably inferior.)

Alone in dissent, Harlan argued that the Louisiana law at issue, which forced separation of white and black passengers on railway cars, was a "badge of servitude" that degraded African-Americans, and claimed that the Court's ruling would become as infamous as its ruling in the Dred Scott case

Dred Scott v. Sandford

Dred Scott v. Sandford, , also known as the Dred Scott Decision, was a ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court that people of African descent brought into the United States and held as slaves were not protected by the Constitution and could never be U.S...

.

He wrote:

Family and personal life

In 1856, Harlan married Malvina French Shanklin, the daughter of an Indiana businessman. Theirs was a happy marriage, which lasted until Harlan's death. Together they had six children, three sons and three daughters. Their eldest son, Richard, became a Presbyterian minister and educator who served as president of Lake Forest CollegeLake Forest College

Lake Forest College, founded in 1857, is a private liberal arts college in Lake Forest, Illinois. The college has 1,500 students representing 47 states and 78 countries....

from 1901 until 1906. Their second son, James S. Harlan

James S. Harlan

James S. Harlan was an American lawyer and commerce specialist, son of U.S. Supreme Court Justice John Marshall Harlan and uncle of Justice John Marshall Harlan II. He was born at Evansville, Indiana, graduated from Princeton University in 1883, and studied law in the office of Melville W. Fuller...

, practiced in Chicago and served as attorney general of Puerto Rico before being appointed to the Interstate Commerce Commission

Interstate Commerce Commission

The Interstate Commerce Commission was a regulatory body in the United States created by the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887. The agency's original purpose was to regulate railroads to ensure fair rates, to eliminate rate discrimination, and to regulate other aspects of common carriers, including...

in 1906 and becoming that body's chairman in 1914. Their youngest son, John Maynard, also practiced in Chicago and served as an alderman

Alderman

An alderman is a member of a municipal assembly or council in many jurisdictions founded upon English law. The term may be titular, denoting a high-ranking member of a borough or county council, a council member chosen by the elected members themselves rather than by popular vote, or a council...

before running unsuccessfully for mayor in both 1897 and 1905; John Maynard's son, John Marshall Harlan II

John Marshall Harlan II

John Marshall Harlan was an American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court from 1955 to 1971. His namesake was his grandfather John Marshall Harlan, another associate justice who served from 1877 to 1911.Harlan was a student at Upper Canada College and Appleby College and...

, served as a Supreme Court Associate Justice from 1955 until 1971.

It is also said that Harlan's attitudes towards civil rights were influenced by the social principles of the Presbyterian Church

Presbyterian Church (USA)

The Presbyterian Church , or PC, is a mainline Protestant Christian denomination in the United States. Part of the Reformed tradition, it is the largest Presbyterian denomination in the U.S...

. During his tenure as a Justice, he taught a Sunday school class at a Presbyterian church in Washington, DC.

Death, honors and legacy

Harlan died on October 14, 1911, after 33 years with the Supreme Court, the third-longest tenure on the court up to that time (and the sixth-longest ever). He was buried in Rock Creek CemeteryRock Creek Cemetery

Rock Creek Cemetery — also Rock Creek Church Yard and Cemetery — is an cemetery with a natural rolling landscape located at Rock Creek Church Road, NW, and Webster Street, NW, off Hawaii Avenue, NE in Washington, D.C.'s Michigan Park neighborhood, near Washington's Petworth neighborhood...

, Washington, D.C. where his body resides along with those of three other justices.

There are collections of Harlan's papers at the University of Louisville

University of Louisville

The University of Louisville is a public university in Louisville, Kentucky. When founded in 1798, it was the first city-owned public university in the United States and one of the first universities chartered west of the Allegheny Mountains. The university is mandated by the Kentucky General...

in Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville is the largest city in the U.S. state of Kentucky, and the county seat of Jefferson County. Since 2003, the city's borders have been coterminous with those of the county because of a city-county merger. The city's population at the 2010 census was 741,096...

, and at the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress

Library of Congress

The Library of Congress is the research library of the United States Congress, de facto national library of the United States, and the oldest federal cultural institution in the United States. Located in three buildings in Washington, D.C., it is the largest library in the world by shelf space and...

in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution....

. Both are open for research. Other papers are collected at many other libraries.

Named for Justice Harlan, the "Harlan Scholars" of the University of Louisville

University of Louisville

The University of Louisville is a public university in Louisville, Kentucky. When founded in 1798, it was the first city-owned public university in the United States and one of the first universities chartered west of the Allegheny Mountains. The university is mandated by the Kentucky General...

/Louis D. Brandeis School of Law

Louis D. Brandeis School of Law

The Louis D. Brandeis School of Law is the law school of the University of Louisville. Established in 1846, it is the oldest law school in Kentucky and the fifth oldest in the country in continuous operation. The law school is named after Justice Louis Dembitz Brandeis, who served on the Supreme...

, is an undergraduate organization for students interested in attending law school

Law school

A law school is an institution specializing in legal education.- Law degrees :- Canada :...

.

Centre College, Harlan's alma mater, instituted the John Marshall Harlan Professorship in Government in 1994 in honor of Harlan's reputation as one of the Supreme Court's greatest justices.

In 2009, with the 200th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln's birth coinciding with the election of the first black American president, Harlan's views on civil rights - far ahead of his time - were celebrated and remembered by many.

See also

- List of Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of United States Chief Justices by time in office

- List of U.S. Supreme Court Justices by time in office

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Fuller Court

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Waite Court

- United States Supreme Court cases during the White Court

External links

- Oyez Project, U.S. Supreme Court Multimedia - John M. Harlan.

- John Marshall Harlan, Bibliography, Biography and location of papers, Sixth Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals.

- Centre's John Marshall Harlan praised as civil rights pioneer (March 5, 2009) at Centre CollegeCentre CollegeCentre College is a private liberal arts college in Danville, Kentucky, USA, a community of approximately 16,000 in Boyle County south of Lexington, KY. Centre is an exclusively undergraduate four-year institution. Centre was founded by Presbyterian leaders, with whom it maintains a loose...

.