Hugo Black

Encyclopedia

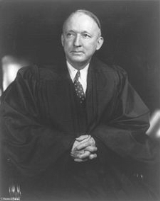

Hugo Lafayette Black was an American politician and jurist. A member of the Democratic Party, Black represented Alabama

in the United States Senate

from 1927 to 1937, and served as an Associate Justice

of the Supreme Court of the United States

from 1937 to 1971. Black was nominated to the Supreme Court by President Franklin D. Roosevelt

and confirmed

by the Senate by a vote of 63 to 13. He was first of nine Roosevelt nominees to the Court, and outlasted all except for William O. Douglas

. Black is widely regarded as one of the most influential Supreme Court justices in the 20th century.

The fifth longest-serving justice in Supreme Court history, Black is noted for his advocacy of a textualist

reading of the United States Constitution

and of the position that the liberties guaranteed in the Bill of Rights

were imposed on the states ("incorporated") by the Fourteenth Amendment

. During his political career, Black was regarded as a staunch supporter of liberal policies and civil liberties. However, Black consistently opposed the doctrine of substantive due process

(the anti-New Deal

Supreme Court cited this concept in such a way as to make it impossible for the government to enact legislation that interfered with the freedom of business owners) and believed that there was no basis in the words of the Constitution for a right to privacy, voting against finding one in Griswold v. Connecticut

. Black endorsed Roosevelt in both the 1932 and 1936 US Presidential elections and was a staunch supporter of the New Deal.

, a poor, isolated rural Clay County

town in the Appalachian

foothills.

Because his brother Orlando had become a medical doctor, Hugo decided at first to follow in his footsteps. At age seventeen, he left school and enrolled at Birmingham Medical School. However, it was Orlando who suggested that Hugo should enroll at the University of Alabama School of Law

. After graduating in June 1906, he moved back to Ashland and established a legal practice. His legal practice was not a success, so Black moved to Birmingham in 1907 to continue his law practice, and came to specialize in labor law and personal injury cases.

Following his defense of an African American forced into a form of commercial slavery following incarceration, Black was befriended by A. O. Lane, a judge connected with the case. When Lane was elected to the Birmingham City Commission in 1911, he asked Black to serve as a police court judge, an experience that would be his only judicial experience prior to the Supreme Court. In 1912, Black resigned that seat in order to return to practicing law full-time. He was not done with public service; in 1914, he began a four-year term as the Jefferson County

Prosecuting Attorney

.

Three years later, during World War I

, Black resigned in order to join the United States Army, eventually reaching the rank of captain. He served in the 81st Field Artillery, but was not assigned to Europe. He joined the Birmingham Civitan Club during this time, eventually serving as president of the group. He remained an active member throughout his life, occasionally contributing articles to Civitan publications.

On February 23, 1921, he married Josephine Foster (1899–1951), with whom he would have three children: Hugo L. Black, II (b. 1922), an attorney; Sterling Foster (b. 1924), and Martha Josephine (b. 1933). Josephine died in 1951; in 1957, Black married Elizabeth Seay DeMeritte.

in the sensationalistic trial for the murder of a Catholic priest Fr. James E. Coyle. He joined the Ku Klux Klan

shortly after, thinking it necessary for his political career. Running for the Senate as the "people's" candidate, Black believed he needed the votes of Klan members. Black would near the end of his life admit that joining the Klan was a mistake, but said "I would have joined any group if it helped get me votes."

Scholars and biographers have recently examined Black's religious views. Ball finds regarding the Klan that Black "sympathized with the group's economic, nativist, and anti-Catholic beliefs." Newman says he "disliked the Catholic Church as an institution" and gave numerous anti-Catholic speeches in his 1926 election campaign to KKK meetings across Alabama.

In 1926, Black sought election to the United States Senate

In 1926, Black sought election to the United States Senate

from Alabama, following the retirement of Senator Oscar Underwood

. Since the Democratic Party dominated Alabama politics at the time, he easily defeated his Republican opponent, E. H. Dryer, winning 80.9% of the vote. He was reelected in 1932, winning 86.3% of the vote against Republican J. Theodore Johnson.

Senator Black gained a reputation as a tenacious investigator. In 1934, for example, he chaired the committee that looked into the contracts awarded to air mail carriers under Postmaster General Walter Folger Brown

, an inquiry which led to the Air Mail scandal

. In order to correct what he termed abuses of "fraud and collusion" resulting from the Air Mail Act of 1930, he introduced the Black-McKellar Bill, later the Air Mail Act of 1934. The following year he participated in a Senate committee's investigation of lobbying

practices. He publicly denounced the "highpowered, deceptive, telegram-fixing, letterframing, Washington-visiting" lobbyists, and advocated legislation requiring them to publicly register their names and salaries.

In 1935, Black became chairman of the Senate Committee on Education and Labor, a position he would hold for the remainder of his Senate career. In 1937 he sponsored the Black-Connery Bill, which sought to establish a national minimum wage

and a maximum workweek of thirty hours. Although the bill was initially rejected in the House of Representatives, a weakened version passed in 1938 (after Black left the Senate), becoming the Fair Labor Standards Act

.

Black was an ardent supporter of President Franklin D. Roosevelt

and the New Deal

. In particular, he was an outspoken advocate of the Judiciary Reorganization Bill of 1937

, popularly known as the court-packing bill, FDR's unsuccessful plan to stack a hostile Supreme Court in his favor by adding more associate justices.

Black would throughout his career as a senator give speeches based on his belief in the ultimate power of the Constitution. He came to see the actions of the anti-New Deal Supreme Court as judicial excess; in his view, the Court was improperly overturning legislation passed by large majorities of Congress.

retired. Roosevelt wanted the replacement to be a "thumping, evangelical New Dealer" who was reasonably young, confirmable by the Senate, and from a region of the country unrepresented on the Court. The three final candidates were Solicitor General Stanley Reed

, Sherman Minton

, and Hugo Black. Roosevelt said Reed "had no fire," and Minton didn't want the appointment at the time. The position would go to Black - a candidate from the South who as a senator had voted for all twenty-four of Roosevelt's major New Deal programs. Roosevelt admired Black's use of the investigative role of the Senate to shape the American mind on reforms, his strong voting record, and his early support, which dated back to 1933.

On August 12, 1937, Roosevelt nominated Black to fill the vacancy. By tradition, a senator nominated for an executive or judicial office was confirmed immediately and without debate. However, when Black was nominated, the Senate departed from this tradition for the first time since 1853; instead of confirming him immediately, it referred the nomination to the Judiciary Committee

. Black was criticized for his presumed bigotry, his cultural roots, and later when it became public, his Klan membership.

The Judiciary Committee recommended Black's confirmation by a vote of 13–4 on August 16 of that year.

The next day the full Senate considered Black's nomination. Rumors relating to Black's involvement in the Ku Klux Klan surfaced among the senators, and two Democratic Senators tried defeating the nomination. However, no conclusive evidence of Black's involvement was available at the time, so after six hours of debate, the Senate voted 63-16 to confirm Black - ten Republicans and six Democrats voted against Black. Alabama Governor Bibb Graves

appointed his own wife, Dixie B. Graves

, to fill Black's vacated seat.

The next month, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

investigated Black's KKK past. Ray Sprigle

won a Pulitzer Prize

for his series of articles revealing Black's involvement in the Klan. However, the controversy soon subsided; the criticism was highly partisan and polls showed that the attacks had little effect on public opinion of Black. Black also addressed public concerns in person: "I did join the Klan. I later resigned. I never rejoined... Before becoming a Senator I dropped the Klan. I have had nothing to do with it since that time. I abandoned it. I completely discontinued any association with the organization. I have never resumed it and never expect to do so."

Black was close friends with Walter White

, the black executive secretary of the NAACP who would help assuage critics of the appointment. Black also had a Jewish law clerk and a Catholic secretary. Chambers v. Florida

(1940), an early case where Black ruled in favor of African American criminal defendants who experienced due process violations, helped put concerns to rest.

and worked to move the Court away from interposing itself in social and economic matters. Black vigorously defended the "plain meaning" of the Constitution, rooted in the ideas of its era, and emphasized the supremacy of the legislature; for Black, the role of the Supreme Court was limited and constitutionally prescribed.

During his early years on the Supreme Court, Black helped reverse several earlier court decisions taking a narrow interpretation of federal power. Many New Deal

laws that would have been struck down under earlier precedents were thus upheld. In 1939 Black was joined on the Supreme Court by Felix Frankfurter

and William O. Douglas

. Douglas voted alongside Black in several cases, especially those involving the First Amendment

, while Frankfurter soon became one of Black's ideological foes.

In the mid-1940s, Justice Black became involved in a bitter dispute with Justice Robert H. Jackson

In the mid-1940s, Justice Black became involved in a bitter dispute with Justice Robert H. Jackson

as a result of Jewell Ridge Coal Corp. v. Local 6167, United Mine Workers (1945). In this case the Court ruled 5–4 in favor of the UMW; Black voted with the majority, while Jackson dissented. However, the coal company requested the Court rehear the case on the grounds that Justice Black should have recused himself, as the mine workers were represented by Black's law partner of 20 years earlier. Under the Supreme Court's rules, each Justice was entitled to determine the propriety of disqualifying himself. Jackson agreed that the petition for rehearing should be denied, but refused to give approval to Black's participation in the case. Ultimately, when the Court unanimously denied the petition for rehearing, Justice Jackson released a short statement, in which Justice Frankfurter joined. The concurrence indicated that Jackson voted to deny the petition not because he approved of Black's participation in the case, but on the "limited grounds" that each Justice was entitled to determine for himself the propriety of recusal. At first the case attracted little public comment, however, after Chief Justice Harlan Stone died in 1946, rumors that President Harry S. Truman

would appoint Jackson as Stone's successor led several newspapers to investigate and report the Jewell Ridge controversy. Black and Douglas allegedly leaked to newspapers that they would resign if Jackson were appointed Chief. Truman ultimately chose Fred M. Vinson

for the position.

Black later clashed with fellow Justice Abe Fortas

during the 1960s. In 1968, a Warren clerk called their feud "one of the most basic animosities of the Court."

in the United States. In several cases the Supreme Court considered, and upheld, the validity of anticommunist laws passed during this era. For example, in American Communications Association v. Douds (1950), the Court upheld a law that required labor union

officials to forswear membership in the Communist Party

. Black dissented, claiming that the law violated the First Amendment

's free speech clause. Similarly, in Dennis v. United States

, , the Court upheld the Smith Act

, which made it a crime to "advocate, abet, advise, or teach the duty, necessity, desirability, or propriety of overthrowing the Government of the United States." The law was often used to prosecute individuals for joining the Communist Party. Black again dissented, writing:

Beginning in the late 1940s, Black wrote decisions relating to the establishment clause, where he insisted on the strict separation of church and state

. The most notable of these was Engel v. Vitale

(1962), which declared state-sanctioned prayer in public schools unconstitutional. This provoked considerable opposition, especially in conservative circles. Efforts to restore school prayer by constitutional amendment failed.

In 1953 Vinson died and was replaced by Earl Warren

. While all members of the Court were New Deal liberals, Black was part of the most liberal wing of the Court, together with Warren, Douglas, William Brennan

, and Arthur Goldberg

. They said the Court had a role beyond that of Congress. Yet while he often voted with them on the Warren Court, he occasionally took his own line on some key cases, most notably Griswold v. Connecticut

(1965), which established that the Constitution protected a right to privacy. In not finding such a right implicit in the Constitution, Black wrote in his dissent that "Many good and able men have eloquently spoken and written... about the duty of this Court to keep the Constitution in tune with the times. ... For myself, I must with all deference reject that philosophy."

Black's most prominent ideological opponent on the Warren Court was John Marshall Harlan II

, who replaced Justice Jackson in 1955. They disagreed on several issues, including the applicability of the Bill of Rights to the states, the scope of the due process clause, and the one man, one vote

principle.

Black's jurisprudence

Black's jurisprudence

is among the most distinctive of any member of the Supreme Court in history and has been influential on justices as diverse as Earl Warren

, William Rehnquist, and Antonin Scalia

.

Black's jurisprudence had three essential components: history, literalism, and absolutism. Black's love of history was rooted in a lifelong love of books, which led him to the belief that historical study was necessary for one to prevent repeating society's past mistakes. Black wrote in 1968 that "power corrupts, and unrestricted power will tempt Supreme Court justices just as history tells us it has tempted other judges."

Second, Black's commitment to literalism involved using the words of the Constitution to restrict the roles of the judiciary - Black would have justices validate the supremacy of the country's legislature, unless the legislature itself was denying people their freedoms. Black wrote: "The Constitution is not deathless; it provides for changing or repealing by the amending process, not by judges but by the people and their chosen representatives." Black would often lecture his colleagues, liberal or conservative, on the Supreme Court about the importance of acting within the limits of the Constitution.

Third, Black's absolutism led him to enforce the rights of the Constitution, rather than attempting to define a meaning, scope, or extent to each right. Black expressed his view on the Bill of Rights in his opinion in the 1947 case, Adamson v. California

, which he saw as his "most significant opinion written:"

and reserved the power of making laws to the legislatures, often scolding his more liberal colleagues for what he saw as judicially-created legislation. Conservative justice John M. Harlan II would say of Black: "No Justice has worn his judicial robes with a keener sense of the limitations that go with them." Black advocated a narrow role of interpretation for justices, opposing a view of justices as social engineers or rewriters of the Constitution. Black opposed enlarging constitutional liberties beyond their literal or historic "plain" meaning, as he saw his more liberal colleagues do. However, he also condemned the actions of those to his right, such as the conservative Four Horsemen of the 1920s and 1930s, who struck down much of the New Deal's legislation.

approach to constitutional interpretation. He took a "literal" or absolutist reading of the provisions of the Bill of Rights and believed that the text of the Constitution is absolutely determinative on any question calling for judicial interpretation, leading to his reputation as a "textualist

" and as a "strict constructionist

". While the text of the constitution was an absolute limitation on the authority of judges in constitutional matters, within the confines of the text judges had a broad and unqualified mandate to enforce constitutional provisions, regardless of current public sentiment, or the feelings of the justices themselves.

Thus, Black refused to join in the efforts of the justices on the Court who sought to abolish capital punishment

in the United States, whose efforts succeeded (temporarily) in the term immediately following Black's death. He claimed that the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendment's reference to takings of "life" meant approval of the death penalty was implicit in the Bill of Rights. He also was not persuaded that a right of privacy was implicit in the Ninth

or Fourteenth amendments, and dissented from the Court's 1965 Griswold

decision which invalidated a conviction for the use of contraceptives. Black said "It belittles that [Fourth] Amendment to talk about it as though it protects nothing but 'privacy'... 'privacy' is a broad, abstract, and ambiguous concept... The constitutional right of privacy is not found in the Constitution."

Justice Black rejected reliance on what he called the "mysterious and uncertain" concept of natural law

. According to Black that theory was vague and arbitrary, and merely allowed judges to impose their personal views on the nation. Instead, he argued that courts should limit themselves to a strict analysis of the actual text of the Constitution. Black was, in addition, an opponent of the "living constitution

" theory. In his dissent to Griswold

(1965), he wrote:

Thus, some have seen Black as an originalist

. David Strauss, for example, hails him as "[t]he most influential originalist judge of the last hundred years." Black insisted that judges rely on the intent of the Framers as well as the "plain meaning" of the Constitution's words and phrases (drawing on the history of the period) when deciding a case. But, unlike modern rightist originalists, Black called for judicial restraint

not usually seen in Court decision-making. The justices of the Court would validate the supremacy of the legislature in public policy-making, unless the legislature was denying people constitutional freedoms. Black stated that the legislature "was fully clothed with the power to govern and to maintain order."

, , Wickard v. Filburn

, , Heart of Atlanta Motel v. United States

, , and Katzenbach v. McClung

, .

In several other federalism cases, however, Black ruled against the federal government. For instance, he partially dissented from South Carolina v. Katzenbach

, , in which the Court upheld the validity of the Voting Rights Act of 1965

. In an attempt to protect the voting rights of African American

s, the act required any state whose population was at least 5% African American to obtain federal approval before changing its voting laws. Black wrote that the law,

Similarly, in Oregon v. Mitchell

(1970), he delivered the opinion of the court holding that the federal government was not entitled to set the voting age

for state elections.

In the law of federal jurisdiction

, Black made a large contribution by authoring the majority opinion in Younger v. Harris

. This case, decided during Black's last year on the Court, has given rise to what is now known as Younger abstention

. According to this doctrine, an important principle of federalism called "comity"—that is, respect by federal courts for state courts—dictates that federal courts abstain from intervening in ongoing state proceedings, absent the most compelling circumstances. The case is also famous for its discussion of what Black calls "Our Federalism," a discussion in which Black expatiates on

Black was an early supporter of the "one man, one vote" standard for apportionment set by Baker v. Carr

. He dissented in support of this view in Baker's predecessor case, Colegrove v. Green

.

(1948), which invalidated the judicial enforcement of racially restrictive covenant

s. Similarly, he was part of the unanimous Brown v. Board of Education

(1954) Court that struck down racial segregation

in public schools. Black remained determined to desegregate the South and would call for the Supreme Court to adopt a position of "immediate desegregation" in 1969's Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education.

Black wrote the court's majority opinion in Korematsu v. United States

, which validated Roosevelt's decision to intern Japanese Americans

on the West Coast

during World War II

. The decision is an example of Black's belief in the limited role of the judiciary; he validated the legislative and executive actions that led to internment, saying "it is unnecessary for us to appraise the possible reasons which might have prompted the order to be used in the form it was."

Black also tended to favor law and order over civil rights activism. This led him to read the Civil Rights Act narrowly. For example, he dissented in a case reversing convictions of sit-in protesters, arguing to limit the scope of the Civil Rights Act. In 1968 he said, “Unfortunately there are some who think that Negroes should have special privileges under the law.” Black felt that actions like protesting, singing, or marching for "good causes" one day could lead to supporting evil causes later on; his sister-in-law explained that Black was "mortally afraid" of protesters. Black opposed the actions of some civil rights and Vietnam War protesters and believed that legislatures first, and courts second, should be responsible for alleviating social wrongs. Black once said he was "vigorously opposed to efforts to extend the First Amendment's freedom of speech beyond speech," to conduct.

", "bad tendency

", "gravity of the evil," "reasonableness," or "balancing." Black would write that the First Amendment is "wholly 'beyond the reach' of federal power to abridge... I do not believe that any federal agencies, including Congress and the Court, have power or authority to subordinate speech and press to what they think are 'more important interests.'"

He believed that the First Amendment erected a metaphorical wall of separation

between church and state. During his career Black wrote several important opinions relating to church-state separation. He delivered the opinion of the court in Everson v. Board of Education

(1947), which held that the establishment clause was applicable not only to the federal government, but also to the states.

Black's majority opinion in McCollum v. Board of Education

(1948) held that the government could not provide religious instruction in public schools. In Torcaso v. Watkins

(1961), he delivered an opinion which affirmed that the states could not use religious tests as qualifications for public office. Similarly, he authored the majority opinion in Engel v. Vitale

(1962), which declared it unconstitutional for states to require the recitation of official prayers in public schools.

Justice Black is often regarded as a leading defender of First Amendment rights such as the freedom of speech and of the press. He refused to accept the doctrine that the freedom of speech could be curtailed on national security grounds. Thus, in New York Times Co. v. United States

(1971), he voted to allow newspapers to publish the Pentagon Papers

despite the Nixon Administration

's contention that publication would have security implications. In his concurring opinion, Black stated,

He rejected the idea that the government was entitled to punish "obscene" speech. Likewise, he argued that defamation

laws abridged the freedom of speech and were therefore unconstitutional. Most members of the Supreme Court rejected both of these views; Black's interpretation did attract the support of Justice Douglas.

However, he did not believe that individuals had the right to speak wherever they pleased. He delivered the majority opinion in Adderley v. Florida

(1966), controversially upholding a trespassing conviction for protestors who demonstrated on government property. He also dissented from Tinker v. Des Moines (1969), in which the Supreme Court ruled that students had the right to wear armbands (as a form of protest) in schools, writing,

Moreover, Black took a narrow view of what constituted "speech" under the First Amendment; for him, "conduct" did not deserve the same protections that "speech" did. For example, he did not believe that flag burning

was speech; in Street v. New York

(1969), he wrote: "It passes my belief that anything in the Federal Constitution bars a State from making the deliberate burning of the American flag an offense." Similarly, he dissented from Cohen v. California

(1971), in which the Court held that wearing a jacket emblazoned with the words "Fuck the Draft" was speech protected by the First Amendment. He agreed that this activity "was mainly conduct, and little speech."

As a Justice, Black held the view that the Court should literally enforce constitutional guarantees, especially the First Amendment free speech clause. He was often labeled an ‘activist’ because of his willingness to review legislation that arguably violated constitutional provisions. Black maintained that literalism was necessary to cabin judicial power."

In a 1968 public interview, reflecting on his most important contributions, Black put his dissent from Adamson v. California "at the top of the list, but then spoke with great eloquence from one of his earliest opinions in Chambers v. Florida (1940)."

than many of his colleagues on the Warren Court. He dissented from Katz v. United States

(1967), in which the Court held that warrantless wiretapping

violated the Fourth Amendment's guarantee against unreasonable search and seizure. He argued that the Fourth Amendment only protected tangible items from physical searches or seizures. Thus, he concluded that telephone conversations were not within the scope of the amendment, and that warrantless wiretapping was consequently permissible.

Justice Black originally believed that the Constitution did not require the exclusion of illegally seized evidence at trials. In his concurrence to Wolf v. Colorado

(1949), he claimed that the exclusionary rule

was "not a command of the Fourth Amendment but ... a judicially created rule of evidence." But he later changed his mind and joined the majority in Mapp v. Ohio

(1961), which applied it to state as well as federal criminal investigations. In his concurrence, he indicated that his support was based on the Fifth Amendment's guarantee of the right against self-incrimination, not on the Fourth Amendment's guarantee against unreasonable searches and seizures. He wrote, "I am still not persuaded that the Fourth Amendment, standing alone, would be enough to bar the introduction into evidence ... seized ... in violation of its commands."

In other instances Black took a fairly broad view of the rights of criminal defendants. He joined the Supreme Court's landmark decision in Miranda v. Arizona

(1966), which required law enforcement officers to warn suspects of their rights

prior to interrogations, and consistently voted to apply the guarantees of the Fourth, Fifth, Sixth

, and Eighth

Amendments at the state level.

Black was the author of the landmark case Gideon v. Wainwright

(1963), which ruled that the states must provide an attorney to an indigent criminal defendant who cannot afford one. Before Gideon, the Court had held that such a requirement applied only to the federal government.

(1833). According to Black, the Fourteenth Amendment, ratified in 1868, "incorporated" the Bill of Rights, or made it binding upon the states as well. In particular, he pointed to the Privileges or Immunities Clause

, "No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States." He proposed that the term "privileges or immunities" encompassed the rights mentioned in the first eight amendments to the Constitution.

Black first expounded this theory of incorporation when the Supreme Court ruled in Adamson v. California

(1947) that the Fifth Amendment

's guarantee against self-incrimination

did not apply to the states. It was during this period of time that Hugo Black became a disciple of John Lilburne

and his claim of ‘freeborn rights’. In an appendix to his dissenting opinion, Justice Black analyzed statements made by those who framed the Fourteenth Amendment, reaching the conclusion that "the Fourteenth Amendment, and particularly its privileges and immunities clause, was a plain application of the Bill of Rights to the states."

Black's theory attracted the support of Justices such as Frank Murphy and William O. Douglas. However, it never achieved the support of a majority of the Court. The most prominent opponents of Black's theory were Justices Felix Frankfurter

and John Marshall Harlan II

. Frankfurter and Harlan argued that the Fourteenth Amendment did not incorporate the Bill of Rights per se, but merely protected rights that are "implicit in the concept of ordered liberty," which was the standard Justice Cardozo had established earlier in Palko v. Connecticut

.

The Supreme Court never accepted the argument that the Fourteenth Amendment incorporated the entirety of the Bill of Rights. However, it did agree that some "fundamental" guarantees were made applicable to the states. For the most part, during the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s, only First Amendment

rights (such as free exercise of religion and freedom of speech) were deemed sufficiently fundamental by the Supreme Court to be incorporated.

However, during the 1960s, the Court under Chief Justice Warren took the process much further, making almost all guarantees of the Bill of Rights binding upon the states. Thus, although the Court failed to accept Black's theory of total incorporation, the end result of its jurisprudence is very close to what Black advocated. Today, the only parts of the first eight amendments that have not been extended to the states are the Third

and Seventh

Amendments, the grand jury

clause of the Fifth Amendment

, the Eighth Amendment

's protection against excessive bail

, and the guarantee of the Sixth Amendment

, as interpreted, that criminal juries be composed of 12 members and be unanimous in their verdicts.

. Most Supreme Court Justices accepted the view that the due process clause encompassed not only procedural guarantees, but also "fundamental fairness" and fundamental rights. Thus, it was argued that due process included a "substantive" component in addition to its "procedural" component.

Black, however, believed that this interpretation of the due process clause was unjustifiably broad. In his dissent to Griswold

, he charged that the doctrine of substantive due process "takes away from Congress and States the power to make laws based on their own judgment of fairness and wisdom, and transfers that power to this Court for ultimate determination." Instead, Black advocated a much narrower interpretation of the clause. In his dissent to In re Winship

, he analyzed the history of the term "due process of law", and concluded: "For me, the only correct meaning of that phrase is that our Government must proceed according to the 'law of the land'—that is, according to written constitutional and statutory provisions as interpreted by court decisions."

Black's view on due process drew from his reading of British history; to him, due process meant all persons were to be tried in accordance with the Bill of Rights' procedural guarantees and in accordance with constitutionally pursuant laws. Black advocated equal treatment by the government for all persons, regardless of wealth, age, or race. Black's view of due process was restrictive in the sense that it was premised on equal procedures; it did not extend to substantive due process. This was in accordance with Black's literalist views. Black did not tie procedural due process exclusively to the Bill of Rights, but he did tie it exclusively to the Bill of Rights combined with other explicit provisions of the Constitution.

None of Black's colleagues shared his interpretation of the due process clause. His chief rival on the issue (and on many other issues) was Felix Frankfurter

, who advocated a substantive view of due process based on "natural law" - if a challenged action did not "shock the conscience" of the jurist, or violate British concepts of fairness, Frankfurter would find no violation of due process of law. John M. Harlan II largely agreed with Frankfurter, and was highly critical of Black's view, indicating his "continued bafflement at... Black's insistence that due process ... does not embody a concept of fundamental fairness" in his Winship concurrence. Since Black's death the Court has continued to apply the doctrine of substantive due process (most notably in Roe v. Wade

, which proclaimed that abortion was a constitutionally protected right).

" principle. He delivered the opinion of the court in Wesberry v. Sanders

(1964), holding that the Constitution required congressional districts in any state to be approximately equal in population. He concluded that the Constitution's command "that Representatives be chosen 'by the People of the several States' means that as nearly as is practicable one man's vote in a congressional election is to be worth as much as another's." Likewise, he voted in favor of Reynolds v. Sims

(1964), which extended the same requirement to state legislative districts on the basis of the equal protection clause.

At the same time, Black did not believe that the equal protection clause made poll tax

es unconstitutional. Thus, he dissented from the Court's ruling in Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections

(1966) invalidating the use of the poll tax as a qualification to vote. He criticized the Court for exceeding its "limited power to interpret the original meaning of the Equal Protection Clause" and for "giving that clause a new meaning which it believes represents a better governmental policy."

Justice Black admitted himself to the National Naval Medical Center

Justice Black admitted himself to the National Naval Medical Center

in Bethesda, Maryland

, in August 1971, and subsequently retired from the Court on September 17. He suffered a stroke two days later and died on September 25.

Services were held at the National Cathedral, and over 1,000 persons attended. Pursuant to Justice Black’s wishes, the coffin was “simple and cheap” and was displayed at the service to show that the costs of burial are not reflective of the worth of the human whose remains were present.

His remains were interred at the Arlington National Cemetery

. He is one of twelve Supreme Court justices buried at Arlington. The others are Harry Andrew Blackmun, William J. Brennan, Arthur Joseph Goldberg, Thurgood Marshall

, Potter Stewart

, William O. Douglas

, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.

, Chief Justice William Howard Taft

, Chief Justice Earl Warren

,Chief Justice Warren Burger, and Chief Justice William Rehnquist

. Justice Black is buried to the right of the main cemetery entrance, and up a hill, 200 yards behind the Taft monument. Black's headstone is "identical in size and shape to the tens of thousands of military headstones in Arlington." It says simply, "Hugo Lafayette Black, Captain, U. S. Army". Between the graves of Justice Black and his first wife there is a simple marble bench with the inscription: "Here Lies a Good Man."

President Richard Nixon

first considered nominating Hershel Friday

to fill the vacant seat, but changed his mind after the American Bar Association

found Friday unqualified. Nixon then nominated Lewis Powell

, who was confirmed by the Senate.

).

In 1986, Black appeared on the Great Americans series

postage stamp

issued by the United States Postal Service

. Along with Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.

he was one of only two Associate Justices to do so until the later inclusions of Thurgood Marshall

, Joseph Story

, Louis Brandeis

, Felix Frankfurter

, and William J. Brennan, Jr.

See, Justice Hugo L. Black 5¢ stamp. and http://www.google.com/imgres?imgurl=http://www.swapmeetdave.com/Stamps/FDC/Goldberg/2172gb10.jpg&imgrefurl=http://www.swapmeetdave.com/Stamps/FDC/Goldberg.htm&usg=__cE56HzCnQEyaWTeXVpYrzvEjAGc=&h=310&w=717&sz=74&hl=en&start=5&zoom=1&tbnid=m1duFUQG98JHhM:&tbnh=61&tbnw=140&prev=/images%3Fq%3DHugo%2BBlack%2BFirst%2Bday%2Bcover%2Bstamp%26hl%3Den%26sa%3DG%26biw%3D666%26bih%3D393%26gbv%3D2%26tbs%3Disch:1&itbs=1Hugo L. Black, First Day] Cover

. In 1987, Congress passed a law sponsored by Ben Erdreich

, H.R. 614, designating the new courthouse building for the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Alabama in Birmingham

, as the "Hugo L. Black United States Courthouse."

An extensive collection of Black's personal, senatorial, and judicial papers is archived at the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress

, where it is open for research.

Justice Black is honored in an exhibit in the Bounds Law Library at the University of Alabama School of Law

. A special Hugo Black collection is maintained by the library.

Black served on the Supreme Court for thirty-four years, making him the fifth longest-serving Justice in Supreme Court history. He was the senior (longest serving) justice on the court for an unprecedented twenty-five years, from the death of Chief Justice Stone on April 22, 1946 to his own retirement on September 17, 1971. As the longest-serving associate justice, he was acting Chief Justice on two occasions: from Stone's death until Vinson

took office on June 24, 1946; and from Vinson's death on September 8, 1953 until Warren

took office on October 5, 1953. There was no interregnum

between the Warren and Burger courts in 1969.

Alabama

Alabama is a state located in the southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Tennessee to the north, Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gulf of Mexico to the south, and Mississippi to the west. Alabama ranks 30th in total land area and ranks second in the size of its inland...

in the United States Senate

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

from 1927 to 1937, and served as an Associate Justice

Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States

Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States are the members of the Supreme Court of the United States other than the Chief Justice of the United States...

of the Supreme Court of the United States

Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States is the highest court in the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all state and federal courts, and original jurisdiction over a small range of cases...

from 1937 to 1971. Black was nominated to the Supreme Court by President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt , also known by his initials, FDR, was the 32nd President of the United States and a central figure in world events during the mid-20th century, leading the United States during a time of worldwide economic crisis and world war...

and confirmed

Advice and consent

Advice and consent is an English phrase frequently used in enacting formulae of bills and in other legal or constitutional contexts, describing a situation in which the executive branch of a government enacts something previously approved of by the legislative branch.-General:The expression is...

by the Senate by a vote of 63 to 13. He was first of nine Roosevelt nominees to the Court, and outlasted all except for William O. Douglas

William O. Douglas

William Orville Douglas was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court. With a term lasting 36 years and 209 days, he is the longest-serving justice in the history of the Supreme Court...

. Black is widely regarded as one of the most influential Supreme Court justices in the 20th century.

The fifth longest-serving justice in Supreme Court history, Black is noted for his advocacy of a textualist

Textualism

Textualism is a formalist theory of statutory interpretation, holding that a statute's ordinary meaning should govern its interpretation, as opposed to inquiries into non-textual sources such as the intention of the legislature in passing the law, the problem it was intended to remedy, or...

reading of the United States Constitution

United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It is the framework for the organization of the United States government and for the relationship of the federal government with the states, citizens, and all people within the United States.The first three...

and of the position that the liberties guaranteed in the Bill of Rights

United States Bill of Rights

The Bill of Rights is the collective name for the first ten amendments to the United States Constitution. These limitations serve to protect the natural rights of liberty and property. They guarantee a number of personal freedoms, limit the government's power in judicial and other proceedings, and...

were imposed on the states ("incorporated") by the Fourteenth Amendment

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was adopted on July 9, 1868, as one of the Reconstruction Amendments.Its Citizenship Clause provides a broad definition of citizenship that overruled the Dred Scott v...

. During his political career, Black was regarded as a staunch supporter of liberal policies and civil liberties. However, Black consistently opposed the doctrine of substantive due process

Substantive due process

Substantive due process is one of the theories of law through which courts enforce limits on legislative and executive powers and authority...

(the anti-New Deal

New Deal

The New Deal was a series of economic programs implemented in the United States between 1933 and 1936. They were passed by the U.S. Congress during the first term of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The programs were Roosevelt's responses to the Great Depression, and focused on what historians call...

Supreme Court cited this concept in such a way as to make it impossible for the government to enact legislation that interfered with the freedom of business owners) and believed that there was no basis in the words of the Constitution for a right to privacy, voting against finding one in Griswold v. Connecticut

Griswold v. Connecticut

Griswold v. Connecticut, , was a landmark case in which the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that the Constitution protected a right to privacy. The case involved a Connecticut law that prohibited the use of contraceptives...

. Black endorsed Roosevelt in both the 1932 and 1936 US Presidential elections and was a staunch supporter of the New Deal.

Early years

Hugo LaFayette Black was the youngest of the eight children of William Lafayette Black and Martha Toland Black. He was born on February 27, 1886, in a small wooden farmhouse in Ashland, AlabamaAshland, Alabama

Ashland is a town in Clay County, Alabama, United States. The population was 1,965 at the 2000 census, at which time it was a city; according to 2005 Census Bureau estimates, the population was 1,885. The town is the county seat of Clay County.-History:...

, a poor, isolated rural Clay County

Clay County, Alabama

Clay County is a county of the US state of Alabama. Its name is in honor of Henry Clay, famous American statesman, member of the United States Senate from Kentucky and United States Secretary of State in the 19th century. As of 2010 the population was 13,932...

town in the Appalachian

Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains #Whether the stressed vowel is or ,#Whether the "ch" is pronounced as a fricative or an affricate , and#Whether the final vowel is the monophthong or the diphthong .), often called the Appalachians, are a system of mountains in eastern North America. The Appalachians...

foothills.

Because his brother Orlando had become a medical doctor, Hugo decided at first to follow in his footsteps. At age seventeen, he left school and enrolled at Birmingham Medical School. However, it was Orlando who suggested that Hugo should enroll at the University of Alabama School of Law

University of Alabama School of Law

The University of Alabama School of Law located in Tuscaloosa, Alabama is a nationally ranked top-tier law school and the only public law school in the state. In total, it is one of five law schools in the state, and one of three that are ABA accredited.The diverse student body, of approximately...

. After graduating in June 1906, he moved back to Ashland and established a legal practice. His legal practice was not a success, so Black moved to Birmingham in 1907 to continue his law practice, and came to specialize in labor law and personal injury cases.

Following his defense of an African American forced into a form of commercial slavery following incarceration, Black was befriended by A. O. Lane, a judge connected with the case. When Lane was elected to the Birmingham City Commission in 1911, he asked Black to serve as a police court judge, an experience that would be his only judicial experience prior to the Supreme Court. In 1912, Black resigned that seat in order to return to practicing law full-time. He was not done with public service; in 1914, he began a four-year term as the Jefferson County

Jefferson County, Alabama

Jefferson County is the most populous county in the U.S. state of Alabama, with its county seat being located in Birmingham.As of the 2010 U.S. Census, the population of Jefferson County was 658,466...

Prosecuting Attorney

Prosecutor

The prosecutor is the chief legal representative of the prosecution in countries with either the common law adversarial system, or the civil law inquisitorial system...

.

Three years later, during World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, Black resigned in order to join the United States Army, eventually reaching the rank of captain. He served in the 81st Field Artillery, but was not assigned to Europe. He joined the Birmingham Civitan Club during this time, eventually serving as president of the group. He remained an active member throughout his life, occasionally contributing articles to Civitan publications.

On February 23, 1921, he married Josephine Foster (1899–1951), with whom he would have three children: Hugo L. Black, II (b. 1922), an attorney; Sterling Foster (b. 1924), and Martha Josephine (b. 1933). Josephine died in 1951; in 1957, Black married Elizabeth Seay DeMeritte.

KKK and anti-Catholicism

In 1921, Black successfully defended E. R. StephensonE. R. Stephenson

Reverend Edwin R. Stephenson was a minister of the now extinct Methodist Episcopal Church, South and a member of the Ku Klux Klan. He shot and killed Catholic priest James Coyle in 1921 in Alabama, but was acquitted of the murder. His main lawyer was Hugo Black.Rev. Stephenson was a son of W. F....

in the sensationalistic trial for the murder of a Catholic priest Fr. James E. Coyle. He joined the Ku Klux Klan

Ku Klux Klan

Ku Klux Klan, often abbreviated KKK and informally known as the Klan, is the name of three distinct past and present far-right organizations in the United States, which have advocated extremist reactionary currents such as white supremacy, white nationalism, and anti-immigration, historically...

shortly after, thinking it necessary for his political career. Running for the Senate as the "people's" candidate, Black believed he needed the votes of Klan members. Black would near the end of his life admit that joining the Klan was a mistake, but said "I would have joined any group if it helped get me votes."

Scholars and biographers have recently examined Black's religious views. Ball finds regarding the Klan that Black "sympathized with the group's economic, nativist, and anti-Catholic beliefs." Newman says he "disliked the Catholic Church as an institution" and gave numerous anti-Catholic speeches in his 1926 election campaign to KKK meetings across Alabama.

Senate career

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

from Alabama, following the retirement of Senator Oscar Underwood

Oscar Underwood

Oscar Wilder Underwood was an American politician.Underwood was born in Louisville, Kentucky, on May 6, 1862. He was the grandson of Joseph R. Underwood, a Kentucky Senator circa 1850. He attended the University of Virginia at Charlottesville...

. Since the Democratic Party dominated Alabama politics at the time, he easily defeated his Republican opponent, E. H. Dryer, winning 80.9% of the vote. He was reelected in 1932, winning 86.3% of the vote against Republican J. Theodore Johnson.

Senator Black gained a reputation as a tenacious investigator. In 1934, for example, he chaired the committee that looked into the contracts awarded to air mail carriers under Postmaster General Walter Folger Brown

Walter Folger Brown

Walter Folger Brown was Postmaster General of the United States from 1929 through 1933 under Herbert Hoover. He was best known for his involvement in the Air Mail scandal...

, an inquiry which led to the Air Mail scandal

Air Mail Scandal

The Air Mail scandal, also known as the Air Mail fiasco, is the name that the American press gave to the political scandal resulting from a congressional investigation of a 1930 meeting , between Postmaster General Walter Folger Brown and the executives of the top airlines, and to the disastrous...

. In order to correct what he termed abuses of "fraud and collusion" resulting from the Air Mail Act of 1930, he introduced the Black-McKellar Bill, later the Air Mail Act of 1934. The following year he participated in a Senate committee's investigation of lobbying

Lobbying

Lobbying is the act of attempting to influence decisions made by officials in the government, most often legislators or members of regulatory agencies. Lobbying is done by various people or groups, from private-sector individuals or corporations, fellow legislators or government officials, or...

practices. He publicly denounced the "highpowered, deceptive, telegram-fixing, letterframing, Washington-visiting" lobbyists, and advocated legislation requiring them to publicly register their names and salaries.

In 1935, Black became chairman of the Senate Committee on Education and Labor, a position he would hold for the remainder of his Senate career. In 1937 he sponsored the Black-Connery Bill, which sought to establish a national minimum wage

Minimum wage

A minimum wage is the lowest hourly, daily or monthly remuneration that employers may legally pay to workers. Equivalently, it is the lowest wage at which workers may sell their labour. Although minimum wage laws are in effect in a great many jurisdictions, there are differences of opinion about...

and a maximum workweek of thirty hours. Although the bill was initially rejected in the House of Representatives, a weakened version passed in 1938 (after Black left the Senate), becoming the Fair Labor Standards Act

Fair Labor Standards Act

The Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 is a federal statute of the United States. The FLSA established a national minimum wage, guaranteed 'time-and-a-half' for overtime in certain jobs, and prohibited most employment of minors in "oppressive child labor," a term that is defined in the statute...

.

Black was an ardent supporter of President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt , also known by his initials, FDR, was the 32nd President of the United States and a central figure in world events during the mid-20th century, leading the United States during a time of worldwide economic crisis and world war...

and the New Deal

New Deal

The New Deal was a series of economic programs implemented in the United States between 1933 and 1936. They were passed by the U.S. Congress during the first term of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The programs were Roosevelt's responses to the Great Depression, and focused on what historians call...

. In particular, he was an outspoken advocate of the Judiciary Reorganization Bill of 1937

Judiciary Reorganization Bill of 1937

The Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937, frequently called the court-packing plan, was a legislative initiative proposed by U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt to add more justices to the U.S. Supreme Court. Roosevelt's purpose was to obtain favorable rulings regarding New Deal legislation that...

, popularly known as the court-packing bill, FDR's unsuccessful plan to stack a hostile Supreme Court in his favor by adding more associate justices.

Black would throughout his career as a senator give speeches based on his belief in the ultimate power of the Constitution. He came to see the actions of the anti-New Deal Supreme Court as judicial excess; in his view, the Court was improperly overturning legislation passed by large majorities of Congress.

Appointment to the Supreme Court

Soon after the failure of the court-packing plan, President Roosevelt obtained his first opportunity to appoint a Supreme Court Justice when conservative Willis Van DevanterWillis Van Devanter

Willis Van Devanter was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court, January 3, 1911 to June 2, 1937.- Early life and career :...

retired. Roosevelt wanted the replacement to be a "thumping, evangelical New Dealer" who was reasonably young, confirmable by the Senate, and from a region of the country unrepresented on the Court. The three final candidates were Solicitor General Stanley Reed

Stanley Forman Reed

Stanley Forman Reed was a noted American attorney who served as United States Solicitor General from 1935 to 1938 and as an Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1938 to 1957. He was the last Supreme Court Justice who did not graduate from law school Stanley Forman Reed (December 31,...

, Sherman Minton

Sherman Minton

Sherman "Shay" Minton was a Democratic United States Senator from Indiana and an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. He was the most educated justice during his time on the Supreme Court, having attended Indiana University, Yale and the Sorbonne...

, and Hugo Black. Roosevelt said Reed "had no fire," and Minton didn't want the appointment at the time. The position would go to Black - a candidate from the South who as a senator had voted for all twenty-four of Roosevelt's major New Deal programs. Roosevelt admired Black's use of the investigative role of the Senate to shape the American mind on reforms, his strong voting record, and his early support, which dated back to 1933.

On August 12, 1937, Roosevelt nominated Black to fill the vacancy. By tradition, a senator nominated for an executive or judicial office was confirmed immediately and without debate. However, when Black was nominated, the Senate departed from this tradition for the first time since 1853; instead of confirming him immediately, it referred the nomination to the Judiciary Committee

United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary

The United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary is a standing committee of the United States Senate, of the United States Congress. The Judiciary Committee, with 18 members, is charged with conducting hearings prior to the Senate votes on confirmation of federal judges nominated by the...

. Black was criticized for his presumed bigotry, his cultural roots, and later when it became public, his Klan membership.

The Judiciary Committee recommended Black's confirmation by a vote of 13–4 on August 16 of that year.

The next day the full Senate considered Black's nomination. Rumors relating to Black's involvement in the Ku Klux Klan surfaced among the senators, and two Democratic Senators tried defeating the nomination. However, no conclusive evidence of Black's involvement was available at the time, so after six hours of debate, the Senate voted 63-16 to confirm Black - ten Republicans and six Democrats voted against Black. Alabama Governor Bibb Graves

Bibb Graves

David Bibb Graves was a Democratic politician and the 38th Governor of Alabama 1927-1931 and 1935–1939, the first Alabama governor to serve two four-year terms.-Early life:...

appointed his own wife, Dixie B. Graves

Dixie Bibb Graves

Dixie Bibb Graves was a United States Senator and former First Lady from the state of Alabama. The first woman Senator from Alabama, she was appointed to the Senate by her husband, then Governor Bibb Graves, to fill the vacancy caused by the resignation of Hugo L. Black...

, to fill Black's vacated seat.

The next month, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, also known simply as the "PG," is the largest daily newspaper serving metropolitan Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA.-Early history:...

investigated Black's KKK past. Ray Sprigle

Ray Sprigle

Ray Sprigle was a Pulitzer Prize winning journalist for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.Sprigle graduated from Ohio State University...

won a Pulitzer Prize

Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prize is a U.S. award for achievements in newspaper and online journalism, literature and musical composition. It was established by American publisher Joseph Pulitzer and is administered by Columbia University in New York City...

for his series of articles revealing Black's involvement in the Klan. However, the controversy soon subsided; the criticism was highly partisan and polls showed that the attacks had little effect on public opinion of Black. Black also addressed public concerns in person: "I did join the Klan. I later resigned. I never rejoined... Before becoming a Senator I dropped the Klan. I have had nothing to do with it since that time. I abandoned it. I completely discontinued any association with the organization. I have never resumed it and never expect to do so."

Black was close friends with Walter White

Walter Francis White

Walter Francis White was a civil rights activist who led the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People for almost a quarter of a century and directed a broad program of legal challenges to segregation and disfranchisement. He was also a journalist, novelist, and essayist...

, the black executive secretary of the NAACP who would help assuage critics of the appointment. Black also had a Jewish law clerk and a Catholic secretary. Chambers v. Florida

Chambers v. Florida

Chambers v. Florida, 309 U.S. 227 , was an important United States Supreme Court case that dealt with the extent that police pressure resulting in a criminal defendant's confession violates the Due Process clause.-Case:...

(1940), an early case where Black ruled in favor of African American criminal defendants who experienced due process violations, helped put concerns to rest.

Supreme Court career

As soon as Black started on the Court, he advocated judicial restraintJudicial restraint

Judicial restraint is a theory of judicial interpretation that encourages judges to limit the exercise of their own power. It asserts that judges should hesitate to strike down laws unless they are obviously unconstitutional...

and worked to move the Court away from interposing itself in social and economic matters. Black vigorously defended the "plain meaning" of the Constitution, rooted in the ideas of its era, and emphasized the supremacy of the legislature; for Black, the role of the Supreme Court was limited and constitutionally prescribed.

During his early years on the Supreme Court, Black helped reverse several earlier court decisions taking a narrow interpretation of federal power. Many New Deal

New Deal

The New Deal was a series of economic programs implemented in the United States between 1933 and 1936. They were passed by the U.S. Congress during the first term of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The programs were Roosevelt's responses to the Great Depression, and focused on what historians call...

laws that would have been struck down under earlier precedents were thus upheld. In 1939 Black was joined on the Supreme Court by Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court.-Early life:Frankfurter was born into a Jewish family on November 15, 1882, in Vienna, Austria, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in Europe. He was the third of six children of Leopold and Emma Frankfurter...

and William O. Douglas

William O. Douglas

William Orville Douglas was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court. With a term lasting 36 years and 209 days, he is the longest-serving justice in the history of the Supreme Court...

. Douglas voted alongside Black in several cases, especially those involving the First Amendment

First Amendment to the United States Constitution

The First Amendment to the United States Constitution is part of the Bill of Rights. The amendment prohibits the making of any law respecting an establishment of religion, impeding the free exercise of religion, abridging the freedom of speech, infringing on the freedom of the press, interfering...

, while Frankfurter soon became one of Black's ideological foes.

Relationship with other justices

Robert H. Jackson

Robert Houghwout Jackson was United States Attorney General and an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court . He was also the chief United States prosecutor at the Nuremberg Trials...

as a result of Jewell Ridge Coal Corp. v. Local 6167, United Mine Workers (1945). In this case the Court ruled 5–4 in favor of the UMW; Black voted with the majority, while Jackson dissented. However, the coal company requested the Court rehear the case on the grounds that Justice Black should have recused himself, as the mine workers were represented by Black's law partner of 20 years earlier. Under the Supreme Court's rules, each Justice was entitled to determine the propriety of disqualifying himself. Jackson agreed that the petition for rehearing should be denied, but refused to give approval to Black's participation in the case. Ultimately, when the Court unanimously denied the petition for rehearing, Justice Jackson released a short statement, in which Justice Frankfurter joined. The concurrence indicated that Jackson voted to deny the petition not because he approved of Black's participation in the case, but on the "limited grounds" that each Justice was entitled to determine for himself the propriety of recusal. At first the case attracted little public comment, however, after Chief Justice Harlan Stone died in 1946, rumors that President Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman was the 33rd President of the United States . As President Franklin D. Roosevelt's third vice president and the 34th Vice President of the United States , he succeeded to the presidency on April 12, 1945, when President Roosevelt died less than three months after beginning his...

would appoint Jackson as Stone's successor led several newspapers to investigate and report the Jewell Ridge controversy. Black and Douglas allegedly leaked to newspapers that they would resign if Jackson were appointed Chief. Truman ultimately chose Fred M. Vinson

Fred M. Vinson

Frederick Moore Vinson served the United States in all three branches of government and was the most prominent member of the Vinson political family. In the legislative branch, he was an elected member of the United States House of Representatives from Louisa, Kentucky, for twelve years...

for the position.

Black later clashed with fellow Justice Abe Fortas

Abe Fortas

Abraham Fortas was a U.S. Supreme Court associate justice from 1965 to 1969. Originally from Tennessee, Fortas became a law professor at Yale, and subsequently advised the Securities and Exchange Commission. He then worked at the Interior Department under Franklin D...

during the 1960s. In 1968, a Warren clerk called their feud "one of the most basic animosities of the Court."

1950s and beyond

Vinson's tenure as Chief Justice coincided with the Red Scare, a period of intense anti-communismAnti-communism

Anti-communism is opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed in reaction to the rise of communism, especially after the 1917 October Revolution in Russia and the beginning of the Cold War in 1947.-Objections to communist theory:...

in the United States. In several cases the Supreme Court considered, and upheld, the validity of anticommunist laws passed during this era. For example, in American Communications Association v. Douds (1950), the Court upheld a law that required labor union

Trade union

A trade union, trades union or labor union is an organization of workers that have banded together to achieve common goals such as better working conditions. The trade union, through its leadership, bargains with the employer on behalf of union members and negotiates labour contracts with...

officials to forswear membership in the Communist Party

Communist Party USA

The Communist Party USA is a Marxist political party in the United States, established in 1919. It has a long, complex history that is closely related to the histories of similar communist parties worldwide and the U.S. labor movement....

. Black dissented, claiming that the law violated the First Amendment

First Amendment to the United States Constitution

The First Amendment to the United States Constitution is part of the Bill of Rights. The amendment prohibits the making of any law respecting an establishment of religion, impeding the free exercise of religion, abridging the freedom of speech, infringing on the freedom of the press, interfering...

's free speech clause. Similarly, in Dennis v. United States

Dennis v. United States

Dennis v. United States, , was a United States Supreme Court case involving Eugene Dennis, general secretary of the Communist Party USA, which found that Dennis did not have a right under the First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States to exercise free speech, publication and assembly,...

, , the Court upheld the Smith Act

Smith Act

The Alien Registration Act or Smith Act of 1940 is a United States federal statute that set criminal penalties for advocating the overthrow of the U.S...

, which made it a crime to "advocate, abet, advise, or teach the duty, necessity, desirability, or propriety of overthrowing the Government of the United States." The law was often used to prosecute individuals for joining the Communist Party. Black again dissented, writing:

"Public opinion being what it now is, few will protest the conviction of these Communist petitioners. There is hope, however, that, in calmer times, when present pressures, passions and fears subside, this or some later Court will restore the First Amendment liberties to the high preferred place where they belong in a free society."

Beginning in the late 1940s, Black wrote decisions relating to the establishment clause, where he insisted on the strict separation of church and state

Separation of church and state

The concept of the separation of church and state refers to the distance in the relationship between organized religion and the nation state....

. The most notable of these was Engel v. Vitale

Engel v. Vitale

Engel v. Vitale, 370 U.S. 421 , was a landmark United States Supreme Court case that determined that it is unconstitutional for state officials to compose an official school prayer and require its recitation in public schools....

(1962), which declared state-sanctioned prayer in public schools unconstitutional. This provoked considerable opposition, especially in conservative circles. Efforts to restore school prayer by constitutional amendment failed.

In 1953 Vinson died and was replaced by Earl Warren

Earl Warren

Earl Warren was the 14th Chief Justice of the United States.He is known for the sweeping decisions of the Warren Court, which ended school segregation and transformed many areas of American law, especially regarding the rights of the accused, ending public-school-sponsored prayer, and requiring...

. While all members of the Court were New Deal liberals, Black was part of the most liberal wing of the Court, together with Warren, Douglas, William Brennan

William J. Brennan, Jr.

William Joseph Brennan, Jr. was an American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court from 1956 to 1990...

, and Arthur Goldberg

Arthur Goldberg

Arthur Joseph Goldberg was an American statesman and jurist who served as the U.S. Secretary of Labor, Supreme Court Justice and Ambassador to the United Nations.-Early life:...

. They said the Court had a role beyond that of Congress. Yet while he often voted with them on the Warren Court, he occasionally took his own line on some key cases, most notably Griswold v. Connecticut

Griswold v. Connecticut

Griswold v. Connecticut, , was a landmark case in which the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that the Constitution protected a right to privacy. The case involved a Connecticut law that prohibited the use of contraceptives...

(1965), which established that the Constitution protected a right to privacy. In not finding such a right implicit in the Constitution, Black wrote in his dissent that "Many good and able men have eloquently spoken and written... about the duty of this Court to keep the Constitution in tune with the times. ... For myself, I must with all deference reject that philosophy."

Black's most prominent ideological opponent on the Warren Court was John Marshall Harlan II

John Marshall Harlan II

John Marshall Harlan was an American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court from 1955 to 1971. His namesake was his grandfather John Marshall Harlan, another associate justice who served from 1877 to 1911.Harlan was a student at Upper Canada College and Appleby College and...

, who replaced Justice Jackson in 1955. They disagreed on several issues, including the applicability of the Bill of Rights to the states, the scope of the due process clause, and the one man, one vote

OMOV

"One man, one vote" is a slogan that has been used in many parts of the world where campaigns have arisen for universal suffrage. It became particularly prevalent in less developed countries, during the period of decolonisation and the struggles for national sovereignty from the late 1940s onwards...

principle.

Jurisprudence

Jurisprudence

Jurisprudence is the theory and philosophy of law. Scholars of jurisprudence, or legal theorists , hope to obtain a deeper understanding of the nature of law, of legal reasoning, legal systems and of legal institutions...

is among the most distinctive of any member of the Supreme Court in history and has been influential on justices as diverse as Earl Warren

Earl Warren

Earl Warren was the 14th Chief Justice of the United States.He is known for the sweeping decisions of the Warren Court, which ended school segregation and transformed many areas of American law, especially regarding the rights of the accused, ending public-school-sponsored prayer, and requiring...

, William Rehnquist, and Antonin Scalia

Antonin Scalia

Antonin Gregory Scalia is an American jurist who serves as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. As the longest-serving justice on the Court, Scalia is the Senior Associate Justice...

.

Black's jurisprudence had three essential components: history, literalism, and absolutism. Black's love of history was rooted in a lifelong love of books, which led him to the belief that historical study was necessary for one to prevent repeating society's past mistakes. Black wrote in 1968 that "power corrupts, and unrestricted power will tempt Supreme Court justices just as history tells us it has tempted other judges."

Second, Black's commitment to literalism involved using the words of the Constitution to restrict the roles of the judiciary - Black would have justices validate the supremacy of the country's legislature, unless the legislature itself was denying people their freedoms. Black wrote: "The Constitution is not deathless; it provides for changing or repealing by the amending process, not by judges but by the people and their chosen representatives." Black would often lecture his colleagues, liberal or conservative, on the Supreme Court about the importance of acting within the limits of the Constitution.

Third, Black's absolutism led him to enforce the rights of the Constitution, rather than attempting to define a meaning, scope, or extent to each right. Black expressed his view on the Bill of Rights in his opinion in the 1947 case, Adamson v. California

Adamson v. California

Adamson v. California, 332 U.S. 46 was a United States Supreme Court case regarding the incorporation of the Fifth Amendment of the Bill of Rights. Its decision is part of a long line of cases that eventually led to the Selective Incorporation Doctrine.-Background:In Adamson v...

, which he saw as his "most significant opinion written:"

"I cannot consider the Bill of Rights to be an outworn 18th century 'strait jacket.' ... Its provisions may be thought outdated abstractions by some. And it is true that they were designed to meet ancient evils. But they are the same kind of human evils that have emerged from century to century wherever excessive power is sought by the few at the expense of the many. In my judgment the people of no nation can lose their liberty so long as a Bill of Rights like ours survives and its basic purposes are conscientiously interpreted, enforced, and respected... I would follow what I believe was the original intention of the Fourteenth Amendment - to extend to all the people the complete protection of the Bill of Rights. To hold that this Court can determine what, if any, provisions of the Bill of Rights will be enforced, and if so to what degree, is to frustrate the great design of a written Constitution.

Judicial Restraint

Black intensely believed in judicial restraintJudicial restraint

Judicial restraint is a theory of judicial interpretation that encourages judges to limit the exercise of their own power. It asserts that judges should hesitate to strike down laws unless they are obviously unconstitutional...

and reserved the power of making laws to the legislatures, often scolding his more liberal colleagues for what he saw as judicially-created legislation. Conservative justice John M. Harlan II would say of Black: "No Justice has worn his judicial robes with a keener sense of the limitations that go with them." Black advocated a narrow role of interpretation for justices, opposing a view of justices as social engineers or rewriters of the Constitution. Black opposed enlarging constitutional liberties beyond their literal or historic "plain" meaning, as he saw his more liberal colleagues do. However, he also condemned the actions of those to his right, such as the conservative Four Horsemen of the 1920s and 1930s, who struck down much of the New Deal's legislation.

Textualism and Originalism

Black was noted for his advocacy of a textualistTextualism

Textualism is a formalist theory of statutory interpretation, holding that a statute's ordinary meaning should govern its interpretation, as opposed to inquiries into non-textual sources such as the intention of the legislature in passing the law, the problem it was intended to remedy, or...