Western Theater of the American Civil War

Encyclopedia

Theater (warfare)

In warfare, a theater, is defined as an area or place within which important military events occur or are progressing. The entirety of the air, land, and sea area that is or that may potentially become involved in war operations....

of the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

.

Theater of operations

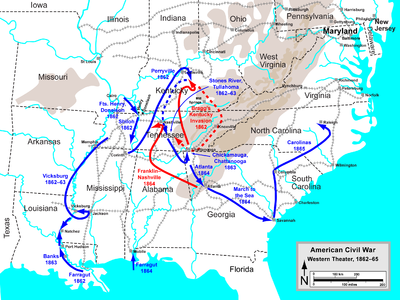

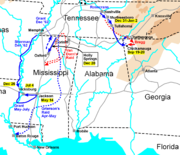

The Western Theater was an area defined by both geography and the sequence of campaigning. It originally represented the area east of the Mississippi RiverMississippi River

The Mississippi River is the largest river system in North America. Flowing entirely in the United States, this river rises in western Minnesota and meanders slowly southwards for to the Mississippi River Delta at the Gulf of Mexico. With its many tributaries, the Mississippi's watershed drains...

and west of the Appalachian Mountains

Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains #Whether the stressed vowel is or ,#Whether the "ch" is pronounced as a fricative or an affricate , and#Whether the final vowel is the monophthong or the diphthong .), often called the Appalachians, are a system of mountains in eastern North America. The Appalachians...

. It excluded operations against the Gulf Coast and the Eastern Seaboard

East Coast of the United States

The East Coast of the United States, also known as the Eastern Seaboard, refers to the easternmost coastal states in the United States, which touch the Atlantic Ocean and stretch up to Canada. The term includes the U.S...

, but as the war progressed and William Tecumseh Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman was an American soldier, businessman, educator and author. He served as a General in the Union Army during the American Civil War , for which he received recognition for his outstanding command of military strategy as well as criticism for the harshness of the "scorched...

's Union

Union Army

The Union Army was the land force that fought for the Union during the American Civil War. It was also known as the Federal Army, the U.S. Army, the Northern Army and the National Army...

armies moved southeast from Chattanooga, Tennessee

Chattanooga, Tennessee

Chattanooga is the fourth-largest city in the US state of Tennessee , with a population of 169,887. It is the seat of Hamilton County...

, in 1864 and 1865, the definition of the theater expanded to encompass their operations in Georgia

Georgia (U.S. state)

Georgia is a state located in the southeastern United States. It was established in 1732, the last of the original Thirteen Colonies. The state is named after King George II of Great Britain. Georgia was the fourth state to ratify the United States Constitution, on January 2, 1788...

and the Carolinas

The Carolinas

The Carolinas is a term used in the United States to refer collectively to the states of North and South Carolina. Together, the two states + have a population of 13,942,126. "Carolina" would be the fifth most populous state behind California, Texas, New York, and Florida...

. For operations west of the Mississippi River see Trans-Mississippi Theater of the American Civil War

Trans-Mississippi Theater of the American Civil War

The Trans-Mississippi Theater of the American Civil War was the major military and naval operations west of the Mississippi River. The area excluded the states and territories bordering the Pacific Ocean, which formed the Pacific Coast Theater of the American Civil War.The campaign classification...

.

The West was by some measures the most important theater of the war. The Confederacy

Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America was a government set up from 1861 to 1865 by 11 Southern slave states of the United States of America that had declared their secession from the U.S...

was forced to defend with limited resources an enormous land mass, which was subject to Union thrusts along multiple avenues of approach, including major rivers that led directly to the agricultural heartland of the South

Southern United States

The Southern United States—commonly referred to as the American South, Dixie, or simply the South—constitutes a large distinctive area in the southeastern and south-central United States...

. Capture of the Mississippi River was one of the key tenets of Union General Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott was a United States Army general, and unsuccessful presidential candidate of the Whig Party in 1852....

's Anaconda Plan

Anaconda Plan

The Anaconda Plan or Scott's Great Snake is the name widely applied to an outline strategy for subduing the seceding states in the American Civil War. Proposed by General-in-Chief Winfield Scott, the plan emphasized the blockade of the Southern ports, and called for an advance down the Mississippi...

.

The Eastern Theater

Eastern Theater of the American Civil War

The Eastern Theater of the American Civil War included the states of Virginia, West Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania, the District of Columbia, and the coastal fortifications and seaports of North Carolina...

received considerably more attention than the Western, both at the time and in subsequent historical accounts. This is due to a number of factors, including the proximity of the opposing capitals, the concentration of newspapers in the major cities of the East, several unanticipated Confederate victories, and the fame of Eastern generals such as Robert E. Lee

Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee was a career military officer who is best known for having commanded the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia in the American Civil War....

, George B. McClellan

George B. McClellan

George Brinton McClellan was a major general during the American Civil War. He organized the famous Army of the Potomac and served briefly as the general-in-chief of the Union Army. Early in the war, McClellan played an important role in raising a well-trained and organized army for the Union...

, and Stonewall Jackson

Stonewall Jackson

ຄຽשת״ׇׂׂׂׂ֣|birth_place= Clarksburg, Virginia |death_place=Guinea Station, Virginia|placeofburial=Stonewall Jackson Memorial CemeteryLexington, Virginia|placeofburial_label= Place of burial|image=...

. Because of this, the progress that Union forces made in defeating Confederate armies in the West and overtaking Confederate territory went nearly unnoticed.

Military historian J. F. C. Fuller has described the Union invasion as an immense turning movement, a left wheel that started in Kentucky

Kentucky

The Commonwealth of Kentucky is a state located in the East Central United States of America. As classified by the United States Census Bureau, Kentucky is a Southern state, more specifically in the East South Central region. Kentucky is one of four U.S. states constituted as a commonwealth...

, headed south down the Mississippi River, and then east through Tennessee

Tennessee

Tennessee is a U.S. state located in the Southeastern United States. It has a population of 6,346,105, making it the nation's 17th-largest state by population, and covers , making it the 36th-largest by total land area...

, Georgia, and the Carolinas. With the exception of the Battle of Chickamauga

Battle of Chickamauga

The Battle of Chickamauga, fought September 19–20, 1863, marked the end of a Union offensive in southeastern Tennessee and northwestern Georgia called the Chickamauga Campaign...

and some daring raids by cavalry

Cavalry

Cavalry or horsemen were soldiers or warriors who fought mounted on horseback. Cavalry were historically the third oldest and the most mobile of the combat arms...

or guerrilla

Guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare and refers to conflicts in which a small group of combatants including, but not limited to, armed civilians use military tactics, such as ambushes, sabotage, raids, the element of surprise, and extraordinary mobility to harass a larger and...

forces, the four years in the West marked a string of almost continuous defeats for the Confederates; or, at best, tactical draws that eventually turned out to be strategic reversals. And the arguably most successful Union generals of the war (Grant

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant was the 18th President of the United States as well as military commander during the Civil War and post-war Reconstruction periods. Under Grant's command, the Union Army defeated the Confederate military and ended the Confederate States of America...

, Thomas

George Henry Thomas

George Henry Thomas was a career United States Army officer and a Union General during the American Civil War, one of the principal commanders in the Western Theater....

, Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman was an American soldier, businessman, educator and author. He served as a General in the Union Army during the American Civil War , for which he received recognition for his outstanding command of military strategy as well as criticism for the harshness of the "scorched...

, and Sheridan

Philip Sheridan

Philip Henry Sheridan was a career United States Army officer and a Union general in the American Civil War. His career was noted for his rapid rise to major general and his close association with Lt. Gen. Ulysses S...

) came from this theater, consistently outclassing most of their Confederate opponents (with the possible exception of cavalry commander Nathan Bedford Forrest

Nathan Bedford Forrest

Nathan Bedford Forrest was a lieutenant general in the Confederate Army during the American Civil War. He is remembered both as a self-educated, innovative cavalry leader during the war and as a leading southern advocate in the postwar years...

).

The campaign classification established by the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

National Park Service

National Park Service

The National Park Service is the U.S. federal agency that manages all national parks, many national monuments, and other conservation and historical properties with various title designations...

is more fine-grained than the one used in this article. Some minor NPS campaigns have been omitted and some have been combined into larger categories. Only a few of the 117 battles the NPS classifies for this theater are described. Boxed text in the right margin show the NPS campaigns associated with each section.

Early operations (June 1861 – January 1862)

Missouri

Missouri is a US state located in the Midwestern United States, bordered by Iowa, Illinois, Kentucky, Tennessee, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Kansas and Nebraska. With a 2010 population of 5,988,927, Missouri is the 18th most populous state in the nation and the fifth most populous in the Midwest. It...

and Kentucky. The loss of either would have been a crippling blow to the Union cause. Primarily because of the successes of Captain Nathaniel Lyon

Nathaniel Lyon

Nathaniel Lyon was the first Union general to be killed in the American Civil War and is noted for his actions in the state of Missouri at the beginning of the conflict....

and his victory at Boonville

Battle of Boonville

The First Battle of Boonville was a minor skirmish of the American Civil War, occurring on June 17, 1861, near Boonville in Cooper County, Missouri. Although casualties were extremely light, the battle's strategic impact was far greater than one might assume from its limited nature...

in June, Missouri was held in the Union. The state of Kentucky, with a pro-Confederate governor and a pro-Union legislature, had declared neutrality between the opposing sides. This neutrality was first violated on September 3, when Confederate Maj. Gen. Leonidas Polk

Leonidas Polk

Leonidas Polk was a Confederate general in the American Civil War who was once a planter in Maury County, Tennessee, and a second cousin of President James K. Polk...

occupied Columbus

Columbus, Kentucky

Columbus is a city in Hickman County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 229 at the 2000 census.-Geography:Columbus is located at .According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of , all of it land....

, considered key to controlling the Lower Mississippi

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the largest river system in North America. Flowing entirely in the United States, this river rises in western Minnesota and meanders slowly southwards for to the Mississippi River Delta at the Gulf of Mexico. With its many tributaries, the Mississippi's watershed drains...

, and two days later Union Brig. Gen.

Brigadier general (United States)

A brigadier general in the United States Army, Air Force, and Marine Corps, is a one-star general officer, with the pay grade of O-7. Brigadier general ranks above a colonel and below major general. Brigadier general is equivalent to the rank of rear admiral in the other uniformed...

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant was the 18th President of the United States as well as military commander during the Civil War and post-war Reconstruction periods. Under Grant's command, the Union Army defeated the Confederate military and ended the Confederate States of America...

, displaying the personal initiative that would characterize his later career, seized Paducah

Paducah, Kentucky

Paducah is the largest city in Kentucky's Jackson Purchase Region and the county seat of McCracken County, Kentucky, United States. It is located at the confluence of the Tennessee River and the Ohio River, halfway between the metropolitan areas of St. Louis, Missouri, to the west and Nashville,...

. Henceforth, neither adversary respected the proclaimed neutrality of the state; while the most of the state government remained loyal to the Union, the pro-Confederate elements of the legislature organized a separate government in Russellville and was admitted into the Confederate States. This sequence of events is considered a victory for the Union because Kentucky never formally sided with the Confederacy, and if the Union had been prevented from maneuvering within Kentucky, its later successful campaigns in Tennessee would have been more difficult.

| Western Theater Campaigns designated by the National Park Service National Park Service The National Park Service is the U.S. federal agency that manages all national parks, many national monuments, and other conservation and historical properties with various title designations... |

|---|

On the Confederate side, General Albert Sidney Johnston

Albert Sidney Johnston

Albert Sidney Johnston served as a general in three different armies: the Texas Army, the United States Army, and the Confederate States Army...

commanded all forces from Arkansas

Arkansas

Arkansas is a state located in the southern region of the United States. Its name is an Algonquian name of the Quapaw Indians. Arkansas shares borders with six states , and its eastern border is largely defined by the Mississippi River...

to the Cumberland Gap

Cumberland Gap

Cumberland Gap is a pass through the Cumberland Mountains region of the Appalachian Mountains, also known as the Cumberland Water Gap, at the juncture of the U.S. states of Tennessee, Kentucky, and Virginia...

. He was faced with the problem of defending a broad front with numerically inferior forces, but he had an excellent system of lateral communications, permitting him to move troops rapidly where they were needed, and he had two able subordinates, Polk and Maj. Gen. William J. Hardee

William J. Hardee

William Joseph Hardee was a career U.S. Army officer, serving during the Second Seminole War and fighting in the Mexican-American War...

. Johnston also gained political support from secessionists in central and western counties of Kentucky via a new Confederate capital at Bowling Green

Bowling Green, Kentucky

Bowling Green is the third-most populous city in the state of Kentucky after Louisville and Lexington, with a population of 58,067 as of the 2010 Census. It is the county seat of Warren County and the principal city of the Bowling Green, Kentucky Metropolitan Statistical Area with an estimated 2009...

, set up by the Russellville Convention. The alternative government was recognized by the Confederate government, which admitted Kentucky into the Confederacy in December 1861. Using the rail system resources of the Mobile and Ohio Railroad

Mobile and Ohio Railroad

The Mobile and Ohio Railroad was a railroad in the Southern U.S. The M&O was chartered in January and February 1848 by the states of Alabama, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Tennessee. It was planned to span the distance between the seaport of Mobile, Alabama and the Ohio River near Cairo, Illinois...

, Polk was able to quickly fortify and equip the Confederate base at Columbus.

The Union military command in the West, however, suffered from a lack of unified command, organized by November into three separate departments: the Department of Kansas

Department of Kansas

The Department of Kansas was a Union Army command department in the Trans-Mississippi Theater during the American Civil War. This department existed in three different forms during the war.-1861:...

, under Maj. Gen. David Hunter

David Hunter

David Hunter was a Union general in the American Civil War. He achieved fame by his unauthorized 1862 order emancipating slaves in three Southern states and as the president of the military commission trying the conspirators involved with the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln.-Early...

, the Department of Missouri, under Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, and the Department of the Ohio

Department of the Ohio

The Department of the Ohio was an administrative military district created by the United States War Department early in the American Civil War to administer the troops in the Northern states near the Ohio River.General Orders No...

, under Brig. Gen. Don Carlos Buell

Don Carlos Buell

Don Carlos Buell was a career United States Army officer who fought in the Seminole War, the Mexican-American War, and the American Civil War. Buell led Union armies in two great Civil War battles—Shiloh and Perryville. The nation was angry at his failure to defeat the outnumbered...

(who had replaced Brig. Gen. William T. Sherman). By January 1862, this disunity of command was apparent because no strategy for operations in the Western theater could be agreed upon. Buell, under political pressure to invade and hold pro-Union East Tennessee

East Tennessee

East Tennessee is a name given to approximately the eastern third of the U.S. state of Tennessee, one of the three Grand Divisions of Tennessee defined in state law. East Tennessee consists of 33 counties, 30 located within the Eastern Time Zone and three counties in the Central Time Zone, namely...

, moved slowly in the direction of Nashville

Nashville, Tennessee

Nashville is the capital of the U.S. state of Tennessee and the county seat of Davidson County. It is located on the Cumberland River in Davidson County, in the north-central part of the state. The city is a center for the health care, publishing, banking and transportation industries, and is home...

, but achieved nothing more substantial toward his goal than a minor victory at Mill Springs

Battle of Mill Springs

The Battle of Mill Springs, also known as the Battle of Fishing Creek in Confederate terminology, and the Battle of Logan's Cross Roads in Union terminology, was fought in Wayne and Pulaski counties, near current Nancy, Kentucky, on January 19, 1862, as part of the American Civil War. It...

under Brig. Gen. George H. Thomas. (Mill Springs was a significant victory in a strategic sense because it broke the end of the Confederate Western defensive line and opened the Cumberland Gap to East Tennessee, but it got Buell no closer to Nashville.) In Halleck's department, Grant demonstrated up the Tennessee River

Tennessee River

The Tennessee River is the largest tributary of the Ohio River. It is approximately 652 miles long and is located in the southeastern United States in the Tennessee Valley. The river was once popularly known as the Cherokee River, among other names...

by attacking the Confederate camp at Belmont

Battle of Belmont

The Battle of Belmont was fought on November 7, 1861, in Mississippi County, Missouri. It was the first combat test in the American Civil War for Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, the future Union Army general in chief and eventual U.S...

to divert attention from Buell's intended advance, which did not occur. On February 1, 1862, after repeated requests by Grant, Halleck authorized Grant to move against Fort Henry

Battle of Fort Henry

The Battle of Fort Henry was fought on February 6, 1862, in western Tennessee, during the American Civil War. It was the first important victory for the Union and Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant in the Western Theater....

on the Tennessee.

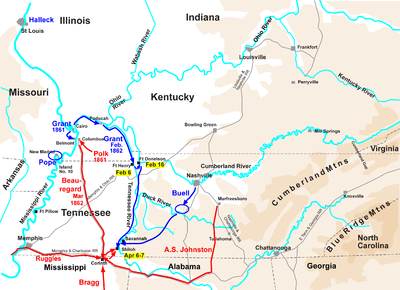

Tennessee, Cumberland, and Mississippi Rivers (February–June 1862)

Grant moved swiftly, starting his troops down the Tennessee River toward Fort HenryBattle of Fort Henry

The Battle of Fort Henry was fought on February 6, 1862, in western Tennessee, during the American Civil War. It was the first important victory for the Union and Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant in the Western Theater....

on river transports on February 2. His operations in the campaign were well coordinated with United States Navy

United States Navy

The United States Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the seven uniformed services of the United States. The U.S. Navy is the largest in the world; its battle fleet tonnage is greater than that of the next 13 largest navies combined. The U.S...

Flag Officer

Flag Officer

A flag officer is a commissioned officer in a nation's armed forces senior enough to be entitled to fly a flag to mark where the officer exercises command. The term usually refers to the senior officers in an English-speaking nation's navy, specifically those who hold any of the admiral ranks; in...

Andrew H. Foote. The fort was poorly situated on a floodplain

Floodplain

A floodplain, or flood plain, is a flat or nearly flat land adjacent a stream or river that stretches from the banks of its channel to the base of the enclosing valley walls and experiences flooding during periods of high discharge...

and virtually indefensible against gunboats, with many of its guns under water. Because of the previous neutrality of Kentucky, the Confederates could not build river defenses at a more strategic location inside the state, so they settled for a site just inside the border of Tennessee. Brig. Gen. Lloyd Tilghman

Lloyd Tilghman

Lloyd Tilghman was a railroad construction engineer and a Confederate general in the American Civil War, killed at the Battle of Champion Hill...

withdrew almost all of his garrison on February 5, moving them across country 11 miles (18 km) to the east to Fort Donelson. With a reduced crew manning the cannons, Tilghman fought an artillery duel with the Union squadron for nearly three hours before he determined that further resistance was useless. The Tennessee River was then open for future Union operations into the South.

Fort Donelson

Battle of Fort Donelson

The Battle of Fort Donelson was fought from February 11 to February 16, 1862, in the Western Theater of the American Civil War. The capture of the fort by Union forces opened the Cumberland River as an avenue for the invasion of the South. The success elevated Brig. Gen. Ulysses S...

, on the Cumberland River

Cumberland River

The Cumberland River is a waterway in the Southern United States. It is long. It starts in Harlan County in far southeastern Kentucky between Pine and Cumberland mountains, flows through southern Kentucky, crosses into northern Tennessee, and then curves back up into western Kentucky before...

, was more defensible than Henry, and Navy assaults on the fort were ineffective. Grant's army marched cross-country in pursuit of Tilghman and attempted immediate assaults on the fort from the rear, but they were unsuccessful. On February 15, the Confederate forces under Brig. Gen. John B. Floyd

John B. Floyd

John Buchanan Floyd was the 31st Governor of Virginia, U.S. Secretary of War, and the Confederate general in the American Civil War who lost the crucial Battle of Fort Donelson.-Early life:...

attempted to escape and launched a surprise assault against the Union right flank

Flanking maneuver

In military tactics, a flanking maneuver, also called a flank attack, is an attack on the sides of an opposing force. If a flanking maneuver succeeds, the opposing force would be surrounded from two or more directions, which significantly reduces the maneuverability of the outflanked force and its...

(commanded by Brig. Gen. John A. McClernand), driving McClernand's division back but not creating the opening they needed to slip away. Grant recovered from this temporary reversal and assaulted the weakened Confederate right. Trapped in the fort and the town of Dover, Tennessee

Dover, Tennessee

Dover is a city in Stewart County, Tennessee, United States, westnorthwest of Nashville on the Cumberland River. An old national cemetery is in Dover. The population was 1,442 at the 2000 census...

, Confederate Brig. Gen. Simon B. Buckner

Simon Bolivar Buckner, Sr.

Simon Bolivar Buckner fought in the United States Army in the Mexican–American War and in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. He later served as the 30th Governor of Kentucky....

surrendered his command of 11,500 men and many needed guns and supplies to Grant's demand for "unconditional surrender". The combined victories at Henry and Donelson were the first significant Union victories in the war, and two major rivers became available for invasions into Tennessee.

Johnston's forward defense was broken. As Grant had anticipated, Polk's position at Columbus was untenable, and he withdrew soon after Donelson fell. Grant had also cut the Memphis and Ohio Railroad that previously had allowed Confederate forces to move laterally in support of each other. General P.G.T. Beauregard had arrived from the East to report to Johnston in February, and he commanded all Confederate forces between the Mississippi and Tennessee Rivers, which effectively divided the unity of command so that Johnston controlled only a small force at Murfreesboro, Tennessee

Murfreesboro, Tennessee

Murfreesboro is a city in and the county seat of Rutherford County, Tennessee, United States. The population was 108,755 according to the United States Census Bureau's 2010 U.S. Census, up from 68,816 residents certified during the 2000 census. The center of population of Tennessee is located in...

. Beauregard planned to concentrate his forces in the vicinity of Corinth, Mississippi

Corinth, Mississippi

Corinth is a city in Alcorn County, Mississippi, United States. The population was 14,054 at the 2000 census. It is the county seat of Alcorn County. Its ZIP codes are 38834 and 38835.- History :...

, and prepare for an offensive. Johnston moved his force to concentrate with Beauregard's by late March.

The preparations for the Union campaign did not proceed smoothly, and Halleck seemed more concerned with his standing in relation to General-in-Chief George B. McClellan

George B. McClellan

George Brinton McClellan was a major general during the American Civil War. He organized the famous Army of the Potomac and served briefly as the general-in-chief of the Union Army. Early in the war, McClellan played an important role in raising a well-trained and organized army for the Union...

than he did with understanding the Confederate Army was divided and could be defeated in detail. Further, he could not agree with his peer, Buell, now in Nashville, on a joint course of action. He sent Grant up the Tennessee River while Buell remained in Nashville. On March 11, President Lincoln appointed Halleck the commander of all forces from the Missouri River

Missouri River

The Missouri River flows through the central United States, and is a tributary of the Mississippi River. It is the longest river in North America and drains the third largest area, though only the thirteenth largest by discharge. The Missouri's watershed encompasses most of the American Great...

to Knoxville, Tennessee

Knoxville, Tennessee

Founded in 1786, Knoxville is the third-largest city in the U.S. state of Tennessee, U.S.A., behind Memphis and Nashville, and is the county seat of Knox County. It is the largest city in East Tennessee, and the second-largest city in the Appalachia region...

, thus achieving the needed unity of command, and Halleck ordered Buell to join Grant's forces at Pittsburg Landing on the Tennessee River.

On April 6, the combined Confederate forces under Beauregard and Johnston surprised Grant's unprepared Army of West Tennessee with a massive dawn assault at Pittsburg Landing in the Battle of Shiloh

Battle of Shiloh

The Battle of Shiloh, also known as the Battle of Pittsburg Landing, was a major battle in the Western Theater of the American Civil War, fought April 6–7, 1862, in southwestern Tennessee. A Union army under Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant had moved via the Tennessee River deep into Tennessee and...

. In the first day of the battle, the Confederate onslaught drove Grant back against the Tennessee but could not defeat him. Johnston was mortally wounded leading an infantry charge that day; he was considered by Jefferson Davis to be the most effective general in the Confederacy at that time. On the second day, April 7, Grant received reinforcements from Buell and launched a counterattack that drove back the Confederates. Grant failed to pursue the retreating enemy and received enormous criticism for this and for the great loss of life—more casualties (almost 24,000) than all previous American battles combined.

Union control of the Mississippi River began to tighten. On April 7, while the Confederates were retreating from Shiloh, Union Maj. Gen. John Pope

John Pope (military officer)

John Pope was a career United States Army officer and Union general in the American Civil War. He had a brief but successful career in the Western Theater, but he is best known for his defeat at the Second Battle of Bull Run in the East.Pope was a graduate of the United States Military Academy in...

defeated Beauregard's isolated force at Island Number 10

Battle of Island Number Ten

The Battle of Island Number Ten was an engagement at the New Madrid or Kentucky Bend on the Mississippi River during the American Civil War, lasting from February 28 to April 8, 1862. The position, an island at the base of a tight double turn in the course of the river, was held by the Confederates...

, opening the river almost as far south as Memphis

Memphis, Tennessee

Memphis is a city in the southwestern corner of the U.S. state of Tennessee, and the county seat of Shelby County. The city is located on the 4th Chickasaw Bluff, south of the confluence of the Wolf and Mississippi rivers....

. On May 18, Admiral David Farragut

David Farragut

David Glasgow Farragut was a flag officer of the United States Navy during the American Civil War. He was the first rear admiral, vice admiral, and admiral in the United States Navy. He is remembered in popular culture for his order at the Battle of Mobile Bay, usually paraphrased: "Damn the...

captured New Orleans

New Orleans, Louisiana

New Orleans is a major United States port and the largest city and metropolitan area in the state of Louisiana. The New Orleans metropolitan area has a population of 1,235,650 as of 2009, the 46th largest in the USA. The New Orleans – Metairie – Bogalusa combined statistical area has a population...

, the South's most significant seaport. Army Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler

Benjamin Franklin Butler (politician)

Benjamin Franklin Butler was an American lawyer and politician who represented Massachusetts in the United States House of Representatives and later served as the 33rd Governor of Massachusetts....

occupied the city with a strong military government that caused considerable resentment among the civilian population.

Although Beauregard had little concentrated strength available to oppose a southward movement by Halleck, the Union general showed insufficient drive to take advantage of the situation. He waited until he assembled a large army, combining the forces of Buell's Army of the Ohio, Grant's Army of West Tennessee, and Pope's Army of the Mississippi, to converge at Pittsburg Landing. He moved slowly in the direction of the critical rail junction at Corinth, taking four weeks to cover the twenty miles (32 km) from Shiloh, stopping nightly to entrench. By May 3, Halleck was within ten miles of the city but took another three weeks to advance eight miles closer to Corinth

Siege of Corinth

The Siege of Corinth was an American Civil War battle fought from April 29 to May 30, 1862, in Corinth, Mississippi.-Background:...

, by which time Halleck was ready to start a massive bombardment of the Confederate defenses. At this time, Beauregard decided not to make a costly defensive stand and withdrew without hostilities during the night of May 29.

Grant did not command directly in the Corinth campaign. Halleck had reorganized his army, giving Grant the powerless position of second-in-command and shuffling divisions from the three armies into three "wings". When Halleck moved east to replace McClellan as general-in-chief, Grant resumed his field command, now named the District of West Tennessee. But before he left, Halleck dispersed his forces, sending Buell towards Chattanooga

Chattanooga, Tennessee

Chattanooga is the fourth-largest city in the US state of Tennessee , with a population of 169,887. It is the seat of Hamilton County...

, Sherman to Memphis, one division to Arkansas, and Rosecrans to hold a covering position around Corinth. Part of Halleck's reason for this was that Lincoln desired to capture eastern Tennessee and protect the Unionists in the region.

Kentucky, Tennessee, and northern Mississippi (June 1862 – January 1863)

Braxton Bragg

Braxton Bragg was a career United States Army officer, and then a general in the Confederate States Army—a principal commander in the Western Theater of the American Civil War and later the military adviser to Confederate President Jefferson Davis.Bragg, a native of North Carolina, was...

succeeded Beauregard (on June 27, for health reasons) in command of his 56,000 troops of the Army of Tennessee, in Tupelo, Mississippi

Tupelo, Mississippi

Tupelo is the largest city in and the county seat of Lee County, Mississippi, United States. It is the seventh largest city in the state of Mississippi, smaller than Meridian, and larger than Greenville. As of the 2000 United States Census, the city's population was 34,211...

, due south of Corinth. But he determined that an advance directly north from Tupelo was not practical. He left Maj. Gens. Sterling Price

Sterling Price

Sterling Price was a lawyer, planter, and politician from the U.S. state of Missouri, who served as the 11th Governor of the state from 1853 to 1857. He also served as a United States Army brigadier general during the Mexican-American War, and a Confederate Army major general in the American Civil...

and Earl Van Dorn

Earl Van Dorn

Earl Van Dorn was a career United States Army officer, fighting with distinction during the Mexican-American War and against several tribes of Native Americans...

to distract Grant and shifted 35,000 men by rail through Mobile, Alabama

Mobile, Alabama

Mobile is the third most populous city in the Southern US state of Alabama and is the county seat of Mobile County. It is located on the Mobile River and the central Gulf Coast of the United States. The population within the city limits was 195,111 during the 2010 census. It is the largest...

, to Chattanooga. Even though he did not leave Tupelo until July 21, he was able to reach Chattanooga before Buell could. Bragg's general plan was to invade Kentucky in a joint operation with Maj. Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith

Edmund Kirby Smith

Edmund Kirby Smith was a career United States Army officer and educator. He served as a general in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War, notable for his command of the Trans-Mississippi Department of the Confederacy after the fall of Vicksburg.After the conflict ended Smith...

, cut Buell's lines of communications, defeat him, and then turn back to defeat Grant.

Kirby Smith left Knoxville on August 14, forced the Union to evacuate Cumberland Gap

Cumberland Gap

Cumberland Gap is a pass through the Cumberland Mountains region of the Appalachian Mountains, also known as the Cumberland Water Gap, at the juncture of the U.S. states of Tennessee, Kentucky, and Virginia...

, defeated a small Union force at the Battle of Richmond (Kentucky), and reached Lexington

Lexington, Kentucky

Lexington is the second-largest city in Kentucky and the 63rd largest in the US. Known as the "Thoroughbred City" and the "Horse Capital of the World", it is located in the heart of Kentucky's Bluegrass region...

on August 30. Bragg departed Chattanooga just before Smith reached Lexington, while Buell moved north from Nashville to Bowling Green. But Bragg moved quickly and by September 14 had interposed his army on Buell's supply lines from Louisville

Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville is the largest city in the U.S. state of Kentucky, and the county seat of Jefferson County. Since 2003, the city's borders have been coterminous with those of the county because of a city-county merger. The city's population at the 2010 census was 741,096...

. Bragg was reluctant to develop this situation because he was outnumbered by Buell; if he had been able to combine with Kirby Smith, he would have been numerically equal, but Smith's command was separate, and Smith believed that Bragg could capture Louisville without his assistance.

Buell, under pressure from the government to take aggressive action, was almost relieved of duty (only the personal reluctance of George H. Thomas to assume command from his superior at the start of a campaign prevented it). As he approached Perryville, Kentucky

Perryville, Kentucky

Perryville is a historical city in western Boyle County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 763 at the 2000 census. It is part of the Danville Micropolitan Statistical Area.-History:...

, he began to concentrate his army in the face of Confederate forces there. Bragg was not initially present with his army, having decided to attend the inauguration ceremony of a Confederate governor of Kentucky in Frankfort

Frankfort, Kentucky

Frankfort is a city in Kentucky that serves as the state capital and the county seat of Franklin County. The population was 27,741 at the 2000 census; by population it is the 5th smallest state capital in the United States...

. On October 8, fighting began at Perryville

Battle of Perryville

The Battle of Perryville, also known as the Battle of Chaplin Hills, was fought on October 8, 1862, in the Chaplin Hills west of Perryville, Kentucky, as the culmination of the Confederate Heartland Offensive during the American Civil War. Confederate Gen. Braxton Bragg's Army of Mississippi won a...

over possession of water sources, and as the fighting escalated, Bragg's Army of Mississippi

Army of Mississippi

There were three organizations known as the Army of Mississippi in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. -Army of Mississippi :This army, at times known by the names Army of the West or Army of the...

achieved some tactical success in an assault against a single corps of Buell's Army of the Ohio

Army of the Ohio

The Army of the Ohio was the name of two Union armies in the American Civil War. The first army became the Army of the Cumberland and the second army was created in 1863.-History:...

. That evening Bragg realized that he was facing Buell's entire army and ordered a retreat to Harrodsburg

Harrodsburg, Kentucky

Harrodsburg is a city in and the county seat of Mercer County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 8,014 at the 2000 census. It is the oldest city in Kentucky.-History:...

, where he was joined by Kirby Smith's Army of Kentucky on October 10. Despite having a strong combined force, Bragg made no attempt to regain the initiative. Buell was equally passive. Bragg retreated through the Cumberland Gap and returned to Murfreesboro by way of Chattanooga.

While Buell was facing Bragg's threat in Kentucky, Confederate operations in northern Mississippi were aimed at preventing Buell's reinforcement by Grant, who was preparing for his upcoming Vicksburg campaign. Halleck had departed for Washington, and Grant was left without interference as commander of the District of West Tennessee. On September 14, Maj. Gen. Sterling Price

Sterling Price

Sterling Price was a lawyer, planter, and politician from the U.S. state of Missouri, who served as the 11th Governor of the state from 1853 to 1857. He also served as a United States Army brigadier general during the Mexican-American War, and a Confederate Army major general in the American Civil...

moved his Confederate Army of the West to Iuka

Iuka, Mississippi

Iuka is a city in Tishomingo County, Mississippi, United States. The population was 3,059 at the 2000 census. It is the county seat of Tishomingo County. Woodall Mountain, the highest point in Mississippi, is located just south of Iuka.- History :...

, 20 miles (32 km) east of Corinth. He intended to link up with Maj. Gen. Earl Van Dorn

Earl Van Dorn

Earl Van Dorn was a career United States Army officer, fighting with distinction during the Mexican-American War and against several tribes of Native Americans...

's Army of West Tennessee

Confederate Army of West Tennessee

The Army of West Tennessee was a short-lived Confederate army led by Maj. Gen. Earl Van Dorn, which fought principally in the Second Battle of Corinth....

and operate against Grant. But Grant sent forces under Maj. Gens. William S. Rosecrans and Edward Ord

Edward Ord

Edward Otho Cresap Ord was the designer of Fort Sam Houston, and a United States Army officer who saw action in the Seminole War, the Indian Wars, and the American Civil War. He commanded an army during the final days of the Civil War, and was instrumental in forcing the surrender of Confederate...

to attack Price's force at Iuka. Rosecrans won a minor victory at the Battle of Iuka

Battle of Iuka

The Battle of Iuka was fought on September 19, 1862, in Iuka, Mississippi, during the American Civil War. In the opening battle of the Iuka-Corinth Campaign, Union Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans stopped the advance of the army of Confederate Maj. Gen. Sterling Price.Maj. Gen. Ulysses S...

(September 19), but poor coordination of forces and an acoustic shadow

Acoustic Shadow

An acoustic shadow is an area through which sound waves fail to propagate, due to topographical obstructions or disruption of the waves via phenomena such as wind currents. A gobo refers to a movable acoustic isolation panel and that makes an acoustic shadow. As one website refers to it, "an...

allowed Price to escape from the intended Union double envelopment.

Price and Van Dorn decided to unite their forces and attack the concentration of Union troops at Corinth and then advance into West

West Tennessee

West Tennessee is one of the three Grand Divisions of the State of Tennessee. Of the three, it is the one that is most sharply defined geographically. Its boundaries are the Mississippi River on the west and the Tennessee River on the east...

or Middle Tennessee

Middle Tennessee

Middle Tennessee is a distinct portion of the state of Tennessee, delineated according to state law as the 41 counties in the Middle Grand Division of Tennessee....

. In the Second Battle of Corinth

Second Battle of Corinth

The Second Battle of Corinth was fought October 3–4, 1862, in Corinth, Mississippi. For the second time in the Iuka-Corinth Campaign, Union Maj. Gen. William S...

(October 3–4), they attacked the fortified Union troops but were repulsed with serious losses. Retreating to the northwest, they escaped pursuit by Rosecrans's exhausted army, but their objectives of threatening Middle Tennessee and supporting Bragg were foiled.

As winter set in, the Union government replaced Buell with Rosecrans. After a period of resupplying and training his army in Nashville, Rosecrans moved against Bragg at Murfreesboro just after Christmas. In the Battle of Stones River

Battle of Stones River

The Battle of Stones River or Second Battle of Murfreesboro , was fought from December 31, 1862, to January 2, 1863, in Middle Tennessee, as the culmination of the Stones River Campaign in the Western Theater of the American Civil War...

, Bragg surprised Rosecrans with a powerful assault on December 31, pushing the Union forces back to a small perimeter against the Tennessee River. But on January 2, 1863, further attempts to assault Rosecrans were beaten back decisively and Bragg withdrew his army southeast to Tullahoma

Tullahoma, Tennessee

-Demographics:As of the census of 2010, there were 18,655 people, 7,717 households, and 5,161 families residing in the city. The racial makeup of the city was 88.1% White, 7.0% African American, 0.2% Native American, 1.2% Asian, 1.1% from other races, and 2.5% from two or more races...

. In proportion to the size of the armies, the casualties at Stones River (about 12,000 on each side) made it the bloodiest battle of the war. At the end of the campaign, Bragg's threat against Kentucky been defeated, and he effectively yielded control of Middle Tennessee.

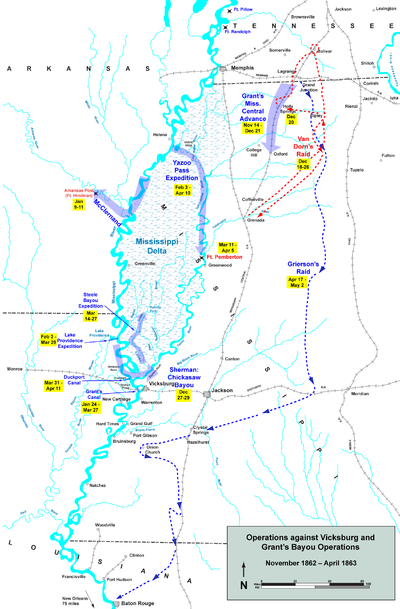

Vicksburg Campaigns (December 1862 – July 1863)

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln was the 16th President of the United States, serving from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. He successfully led his country through a great constitutional, military and moral crisis – the American Civil War – preserving the Union, while ending slavery, and...

believed that the river fortress city of Vicksburg, Mississippi

Vicksburg, Mississippi

Vicksburg is a city in Warren County, Mississippi, United States. It is the only city in Warren County. It is located northwest of New Orleans on the Mississippi and Yazoo rivers, and due west of Jackson, the state capital. In 1900, 14,834 people lived in Vicksburg; in 1910, 20,814; in 1920,...

, was a key to winning the war. Vicksburg and Port Hudson

Siege of Port Hudson

The Siege of Port Hudson occurred from May 22 to July 9, 1863, when Union Army troops assaulted and then surrounded the Mississippi River town of Port Hudson, Louisiana, during the American Civil War....

were the last remaining strongholds that prevented full Union control of the Mississippi River. Situated on high bluffs overlooking a sharp bend in the river and called the "Gibraltar

Gibraltar

Gibraltar is a British overseas territory located on the southern end of the Iberian Peninsula at the entrance of the Mediterranean. A peninsula with an area of , it has a northern border with Andalusia, Spain. The Rock of Gibraltar is the major landmark of the region...

of the Mississippi", Vicksburg was nearly invulnerable to naval assault. Admiral David Farragut

David Farragut

David Glasgow Farragut was a flag officer of the United States Navy during the American Civil War. He was the first rear admiral, vice admiral, and admiral in the United States Navy. He is remembered in popular culture for his order at the Battle of Mobile Bay, usually paraphrased: "Damn the...

had found this directly in his failed operations of May 1862.

The overall plan to capture Vicksburg was for Ulysses S. Grant to move south from Memphis and Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks to move north from Baton Rouge

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

Baton Rouge is the capital of the U.S. state of Louisiana. It is located in East Baton Rouge Parish and is the second-largest city in the state.Baton Rouge is a major industrial, petrochemical, medical, and research center of the American South...

. Banks's advance was slow to develop and bogged down at Port Hudson, offering little assistance to Grant.

First campaign

Grant's first campaign was a two-pronged movement. William T. Sherman sailed down the Mississippi River with 32,000 men while Grant was to move in parallel through Mississippi by railroad with 40,000. Grant advanced 80 miles (130 km), but his supply lines were cut by Confederate cavalry under Earl Van DornEarl Van Dorn

Earl Van Dorn was a career United States Army officer, fighting with distinction during the Mexican-American War and against several tribes of Native Americans...

at Holly Springs

Holly Springs, Mississippi

Holly Springs is a city in Marshall County, Mississippi, United States. The population was 7,957 at the 2000 census. It is the county seat of Marshall County. A short drive from Memphis, Tennessee, Holly Springs is the site of a number of well-preserved antebellum homes and other structures and...

, forcing him to fall back. Sherman reached the Yazoo River

Yazoo River

The Yazoo River is a river in the U.S. state of Mississippi.The Yazoo River was named by French explorer La Salle in 1682 as "Rivière des Yazous" in reference to the Yazoo tribe living near the river's mouth. The exact meaning of the term is unclear...

just north of the city of Vicksburg, but without support from Grant's half of the mission, he was repulsed in bloody assaults against Chickasaw Bayou

Battle of Chickasaw Bayou

The Battle of Chickasaw Bayou, also called Walnut Hills, fought December 26–29, 1862, was the opening engagement of the Vicksburg Campaign during the American Civil War. Confederate forces under Lt. Gen. John C. Pemberton repulsed an advance by Union Maj. Gen. William T...

in late December.

Political considerations then intruded. Illinois

Illinois

Illinois is the fifth-most populous state of the United States of America, and is often noted for being a microcosm of the entire country. With Chicago in the northeast, small industrial cities and great agricultural productivity in central and northern Illinois, and natural resources like coal,...

politician and Maj. Gen. John A. McClernand obtained permission from Lincoln to recruit an army in southern Illinois and command it on a river-born expedition aimed at Vicksburg. He was able to get Sherman's corps assigned to him, but it departed Memphis before McClernand could arrive. When Sherman returned from the Yazoo, McClernand asserted control. He inexplicably detoured from his primary objective by capturing Arkansas Post on the Arkansas River

Arkansas River

The Arkansas River is a major tributary of the Mississippi River. The Arkansas generally flows to the east and southeast as it traverses the U.S. states of Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas. The river's initial basin starts in the Western United States in Colorado, specifically the Arkansas...

, but before he could resume his main advance, Grant had reasserted control, and McClernand became a corps commander in Grant's army. For the rest of the winter, Grant attempted five separate projects to reach the city by moving through or reengineering, rivers, canals, and bayous to the north of Vicksburg. All five were unsuccessful; Grant explained afterward that he had expected these setbacks and was simply attempting to keep his army busy and motivated, but many historians believe he really hoped that some would succeed and that they were too ambitious.

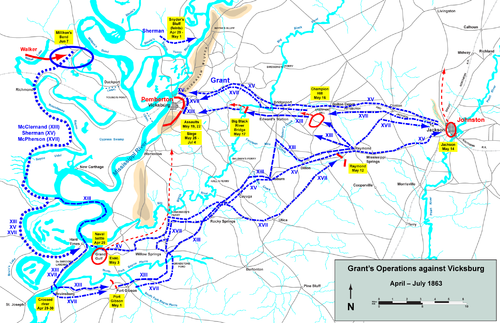

Second campaign

Benjamin Grierson

Benjamin Henry Grierson was a music teacher and then a career officer in the United States Army. He was a cavalry general in the volunteer Union Army during the American Civil War and later led troops in the American Old West...

, known as Grierson's Raid

Grierson's Raid

Grierson's Raid was a Union cavalry raid during the Vicksburg Campaign of the American Civil War. It ran from April 17 to May 2, 1863, as a diversion from Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant's main attack plan on Vicksburg, Mississippi....

. The former was inconclusive, but the latter was a success. Grierson was able to draw out significant Confederate forces, dispersing them around the state.

Grant faced two Confederate armies in his campaign: the Vicksburg garrison, commanded by Maj. Gen. John C. Pemberton

John C. Pemberton

John Clifford Pemberton , was a career United States Army officer who fought in the Seminole Wars and with distinction during the Mexican–American War. He also served as a Confederate general during the American Civil War, noted for his defeat and surrender in the critical Siege of Vicksburg in...

, and forces in Jackson

Jackson, Mississippi

Jackson is the capital and the most populous city of the US state of Mississippi. It is one of two county seats of Hinds County ,. The population of the city declined from 184,256 at the 2000 census to 173,514 at the 2010 census...

, commanded by Gen. Joseph E. Johnston

Joseph E. Johnston

Joseph Eggleston Johnston was a career U.S. Army officer, serving with distinction in the Mexican-American War and Seminole Wars, and was also one of the most senior general officers in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War...

, the overall theater commander. Rather than simply heading directly north to the city, Grant chose to cut the line of communications (and reinforcement) between the two Confederate armies. His army headed swiftly northeast toward Jackson. Meanwhile, Grant brought with him a limited supply line. The conventional history of the campaign indicates that he cut loose from all of his supplies, perplexing Pemberton, who attempted to interdict his nonexistent lines at Raymond

Battle of Raymond

The Battle of Raymond was fought on May 12, 1863, near Raymond, Mississippi, during the Vicksburg Campaign of the American Civil War. The bitter fight pitted elements of Union Army Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant's Army of the Tennessee against Confederate forces of Lt. Gen. John C. Pemberton's...

on May 12. In reality, Grant relied on the local economy to provide him only foodstuffs for men and animals, but there was a constant stream of wagons carrying ammunition, coffee, hardtack, salt, and other supplies for his army.

Sherman's corps captured Jackson

Battle of Jackson (MS)

The Battle of Jackson, fought on May 14, 1863, in Jackson, Mississippi, was part of the Vicksburg Campaign in the American Civil War. Union commander Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and the Army of the Tennessee defeated Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston, seizing the city, cutting supply lines, and...

on May 14. The entire army then turned west to confront Pemberton in front of Vicksburg. The decisive battle was at Champion Hill

Battle of Champion Hill

The Battle of Champion Hill, or Bakers Creek, fought May 16, 1863, was the pivotal battle in the Vicksburg Campaign of the American Civil War. Union commander Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and the Army of the Tennessee pursued the retreating Confederate Lt. Gen. John C...

, the effective last stand for Pemberton before he withdrew into his entrenchments around the city. Grant's army assaulted the Confederate works twice at great cost at the start of the Siege of Vicksburg but then settled in for a lengthy siege.

The soldiers and civilians in Vicksburg suffered greatly from Union bombardment and impending starvation. They clung to hope that General Johnston would arrive with reinforcements, but Johnston was both cut off and too cautious. On July 4, Pemberton surrendered his army and the city to Grant. In conjunction with the defeat of Robert E. Lee

Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee was a career military officer who is best known for having commanded the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia in the American Civil War....

at the Battle of Gettysburg

Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg , was fought July 1–3, 1863, in and around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. The battle with the largest number of casualties in the American Civil War, it is often described as the war's turning point. Union Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade's Army of the Potomac...

the previous day, Vicksburg is widely considered one of the turning points

Turning point of the American Civil War

There is widespread disagreement over the turning point of the American Civil War. The idea of a turning point is an event after which most observers would agree that the eventual outcome was inevitable. While the Battle of Gettysburg is the most widely cited , there are several other arguable...

of the war. By July 8, after Banks captured Port Hudson, the entire Mississippi River was in Union hands, and the Confederacy was split in two.

Tullahoma, Chickamauga, and Chattanooga (June–December 1863)

Abel Streight

Abel D. Streight was a peace time lumber merchant and publisher, and was a Union Army general in the American Civil War. His command precipitated a notable cavalry raid in 1863, known as Streight's Raid...

moved against the railroad that supplied Bragg's army in Middle Tennessee, hoping it would cause them to withdraw to Georgia. Streight's brigade raided through Mississippi and Alabama, fighting against Nathan Bedford Forrest

Nathan Bedford Forrest

Nathan Bedford Forrest was a lieutenant general in the Confederate Army during the American Civil War. He is remembered both as a self-educated, innovative cavalry leader during the war and as a leading southern advocate in the postwar years...

. Streight's Raid

Streight's Raid

Streight's Raid took place from 19 April to 3 May, 1863 in northern Alabama. It was led by Colonel Abel D. Streight, who's goal was to destroy parts of the Western and Atlantic railroad, which was supplying the Confederate Army of Tennessee...

ended when his exhausted men surrendered near Rome, Georgia

Rome, Georgia

Located in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains, Rome is the largest city and the county seat of Floyd County, Georgia, United States. It is the principal city of the Rome, Georgia Metropolitan Statistical Area which encompasses all of Floyd County...

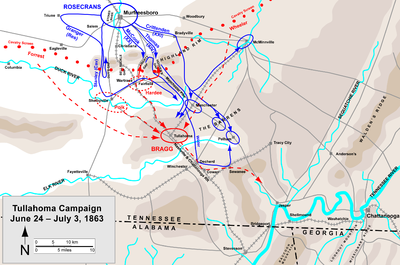

, on May 3. In June, Rosecrans finally advanced against Bragg in a brilliant, almost bloodless, campaign of maneuver, the Tullahoma Campaign

Tullahoma Campaign

The Tullahoma Campaign or Middle Tennessee Campaign was fought between June 24 and July 3, 1863, during the American Civil War. The Union Army of the Cumberland, commanded by Maj. Gen. William S...

, and drove Bragg from Middle Tennessee.

During this period, Brig. Gen. John Hunt Morgan

John Hunt Morgan

John Hunt Morgan was a Confederate general and cavalry officer in the American Civil War.Morgan is best known for Morgan's Raid when, in 1863, he and his men rode over 1,000 miles covering a region from Tennessee, up through Kentucky, into Indiana and on to southern Ohio...

and his 2,460 Confederate cavalrymen rode west from Sparta

Sparta, Tennessee

Sparta is a city in White County, Tennessee, United States. The population was 4,599 at the 2000 census. It is the county seat of White County. It was the hometown of Lester Flatt of the bluegrass music legends Flatt and Scruggs.-Geography:...

in middle Tennessee

Tennessee

Tennessee is a U.S. state located in the Southeastern United States. It has a population of 6,346,105, making it the nation's 17th-largest state by population, and covers , making it the 36th-largest by total land area...

on June 11, intending to divert the attention of Ambrose Burnside

Ambrose Burnside

Ambrose Everett Burnside was an American soldier, railroad executive, inventor, industrialist, and politician from Rhode Island, serving as governor and a U.S. Senator...

's Army of the Ohio

Army of the Ohio

The Army of the Ohio was the name of two Union armies in the American Civil War. The first army became the Army of the Cumberland and the second army was created in 1863.-History:...

, which was moving toward Knoxville, from Southern forces in the state. At the start of the Tullahoma Campaign, Morgan moved northward. For 46 days as they rode over 1,000 miles (1,600 km), Morgan’s cavalrymen terrorized a region from Tennessee to northern Ohio, destroying bridges, railroads, and government stores before being captured; in November they made a daring escape from the Ohio Penitentiary, at Columbus, Ohio

Columbus, Ohio

Columbus is the capital of and the largest city in the U.S. state of Ohio. The broader metropolitan area encompasses several counties and is the third largest in Ohio behind those of Cleveland and Cincinnati. Columbus is the third largest city in the American Midwest, and the fifteenth largest city...

, and returned to the South.

James Longstreet

James Longstreet was one of the foremost Confederate generals of the American Civil War and the principal subordinate to General Robert E. Lee, who called him his "Old War Horse." He served under Lee as a corps commander for many of the famous battles fought by the Army of Northern Virginia in the...

) from Virginia. Rosecrans pursued Bragg into the rugged mountains of northwestern Georgia, only to find that a trap had been set. Bragg started the Battle of Chickamauga

Battle of Chickamauga

The Battle of Chickamauga, fought September 19–20, 1863, marked the end of a Union offensive in southeastern Tennessee and northwestern Georgia called the Chickamauga Campaign...

(September 19–20, 1863) when he launched a three-division assault against the corps of George H. Thomas. A command misunderstanding allowed a major gap to appear in the Union line as reinforcements arrived, and Longstreet was able to drive his corps into that gap and send the Union Army into retreat. If not for the defensive stand by a portion of the line led by Thomas ("The Rock of Chickamauga"), the Union Army would have been completely routed. Rosecrans, devastated by his defeat, withdrew his army to Chattanooga, where Bragg besieged it, occupying the high ground dominating the city.

Back in Vicksburg, Grant was resting his army and planning for a campaign that would capture Mobile

Mobile, Alabama

Mobile is the third most populous city in the Southern US state of Alabama and is the county seat of Mobile County. It is located on the Mobile River and the central Gulf Coast of the United States. The population within the city limits was 195,111 during the 2010 census. It is the largest...

and push east. But when news of the dire straits of Rosecrans's Army of the Cumberland reached Washington, Grant was ordered to rescue them. On October 17, he was given command of the Military Division of the Mississippi, controlling all of the armies in the Western Theater. He replaced Rosecrans with Thomas and traveled to Chattanooga, where he approved a plan to open a new supply line (the "Cracker Line"), allowing supplies and reinforcements to reach the city. Soon the troops were joined by 40,000 more, from the Army of the Tennessee under Sherman and from the Army of the Potomac

Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the major Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War.-History:The Army of the Potomac was created in 1861, but was then only the size of a corps . Its nucleus was called the Army of Northeastern Virginia, under Brig. Gen...

under Joseph Hooker

Joseph Hooker

Joseph Hooker was a career United States Army officer, achieving the rank of major general in the Union Army during the American Civil War. Although he served throughout the war, usually with distinction, Hooker is best remembered for his stunning defeat by Confederate General Robert E...

. While the Union army expanded, the Confederate army contracted; Bragg dispatched Longstreet's corps to Knoxville to hold off an advance by Burnside.

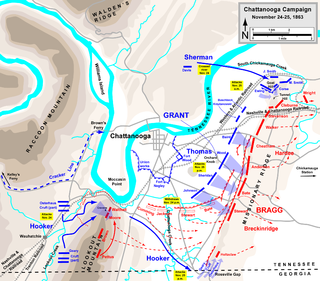

Chattanooga Campaign

The Chattanooga Campaign was a series of maneuvers and battles in October and November 1863, during the American Civil War. Following the defeat of Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans's Union Army of the Cumberland at the Battle of Chickamauga in September, the Confederate Army of Tennessee under Gen...

began in earnest on November 24, 1863, as Hooker took Lookout Mountain

Battle of Lookout Mountain

The Battle of Lookout Mountain was fought November 24, 1863, as part of the Chattanooga Campaign of the American Civil War. Union forces under Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker assaulted Lookout Mountain, Chattanooga, Tennessee, and defeated Confederate forces commanded by Maj. Gen. Carter L. Stevenson....

, which is one of two dominant peaks over the city. The next day, Grant planned a double envelopment of Bragg's position on the other mountain, Missionary Ridge

Battle of Missionary Ridge

The Battle of Missionary Ridge was fought November 25, 1863, as part of the Chattanooga Campaign of the American Civil War. Following the Union victory in the Battle of Lookout Mountain on November 24, Union forces under Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant assaulted Missionary Ridge and defeated the...

. Sherman was to attack from the north, Hooker from the south, and Thomas was to hold the center. But Sherman's attack bogged down in confusion, and Grant ordered Thomas to launch a minor attack as a diversion to relieve pressure on Sherman. Thomas's troops, caught up in enthusiasm and anxious to redeem themselves after their humiliation at Chickamauga, continued their initial attack by charging up the imposing ridge, breaking the Confederate line and causing them to retreat. Chattanooga was saved; along with the failure of Longstreet's Knoxville Campaign

Knoxville Campaign

The Knoxville Campaign was a series of American Civil War battles and maneuvers in East Tennessee during the fall of 1863. Union forces under Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside occupied Knoxville, Tennessee, and Confederate forces under Lt. Gen. James Longstreet were detached from Gen...

against Burnside, politically sensitive eastern Tennessee was free of Confederate control. An avenue of invasion pointed directly to Atlanta

Atlanta, Georgia

Atlanta is the capital and most populous city in the U.S. state of Georgia. According to the 2010 census, Atlanta's population is 420,003. Atlanta is the cultural and economic center of the Atlanta metropolitan area, which is home to 5,268,860 people and is the ninth largest metropolitan area in...

and the heart of the Confederacy. Bragg, whose personal friendship with Confederate President Jefferson Davis

Jefferson Davis

Jefferson Finis Davis , also known as Jeff Davis, was an American statesman and leader of the Confederacy during the American Civil War, serving as President for its entire history. He was born in Kentucky to Samuel and Jane Davis...

saved his command following his defeats at Perryville and Stones River, was finally relieved of duty and replaced by General Joseph E. Johnston

Joseph E. Johnston

Joseph Eggleston Johnston was a career U.S. Army officer, serving with distinction in the Mexican-American War and Seminole Wars, and was also one of the most senior general officers in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War...

.

Atlanta Campaign (May–September 1864)

Lieutenant General (United States)

In the United States Army, the United States Air Force and the United States Marine Corps, lieutenant general is a three-star general officer rank, with the pay grade of O-9. Lieutenant general ranks above major general and below general...

and went east to assume command of all the Union armies. Sherman succeeded him in command of the Military Division of the Mississippi. Grant devised a strategy for simultaneous advances across the Confederacy. It was intended to destroy or fix Robert E. Lee's army in Virginia with three major thrusts (under Meade, Butler

Benjamin Franklin Butler (politician)

Benjamin Franklin Butler was an American lawyer and politician who represented Massachusetts in the United States House of Representatives and later served as the 33rd Governor of Massachusetts....

, and Sigel

Franz Sigel

Franz Sigel was a German military officer, revolutionist and immigrant to the United States who was a teacher, newspaperman, politician, and served as a Union major general in the American Civil War.-Early life:...

) launched in the direction of Richmond and in the Shenandoah Valley

Shenandoah Valley

The Shenandoah Valley is both a geographic valley and cultural region of western Virginia and West Virginia in the United States. The valley is bounded to the east by the Blue Ridge Mountains, to the west by the eastern front of the Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians , to the north by the Potomac River...

; capture Mobile with an army under Nathaniel Banks; and destroy Johnston's army while driving toward Atlanta. Most of the initiatives failed: Butler became bogged down in the Bermuda Hundred Campaign

Bermuda Hundred Campaign

The Bermuda Hundred Campaign was a series of battles fought at the town of Bermuda Hundred, outside Richmond, Virginia, during May 1864 in the American Civil War. Union Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler, commanding the Army of the James, threatened Richmond from the east but was stopped by forces under ...

; Sigel was quickly defeated in the valley; Banks became occupied in the ill-fated Red River Campaign

Red River Campaign

The Red River Campaign or Red River Expedition consisted of a series of battles fought along the Red River in Louisiana during the American Civil War from March 10 to May 22, 1864. The campaign was a Union initiative, fought between approximately 30,000 Union troops under the command of Maj. Gen....

; Meade and Grant experienced many setbacks and much bloodshed in the Overland Campaign

Overland Campaign

The Overland Campaign, also known as Grant's Overland Campaign and the Wilderness Campaign, was a series of battles fought in Virginia during May and June 1864, in the American Civil War. Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, general-in-chief of all Union armies, directed the actions of the Army of the...

before finally settling down to a siege of Petersburg

Siege of Petersburg

The Richmond–Petersburg Campaign was a series of battles around Petersburg, Virginia, fought from June 9, 1864, to March 25, 1865, during the American Civil War...

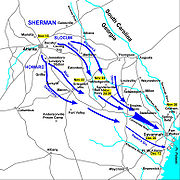

. Sherman's Atlanta Campaign

Atlanta Campaign

The Atlanta Campaign was a series of battles fought in the Western Theater of the American Civil War throughout northwest Georgia and the area around Atlanta during the summer of 1864. Union Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman invaded Georgia from the vicinity of Chattanooga, Tennessee, beginning in May...

was more successful.

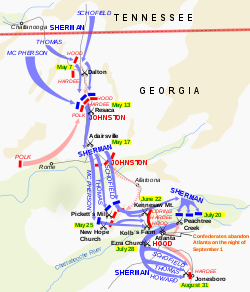

At the start of the campaign, Sherman's Military Division of the Mississippi consisted of three armies: James B. McPherson

James B. McPherson

James Birdseye McPherson was a career United States Army officer who served as a General in the Union Army during the American Civil War...

's Army of the Tennessee

Army of the Tennessee

The Army of the Tennessee was a Union army in the Western Theater of the American Civil War, named for the Tennessee River. It should not be confused with the similarly named Army of Tennessee, a Confederate army named after the State of Tennessee....

(Sherman's old army under Grant), John M. Schofield's Army of the Ohio

Army of the Ohio

The Army of the Ohio was the name of two Union armies in the American Civil War. The first army became the Army of the Cumberland and the second army was created in 1863.-History:...

, and George H. Thomas's Army of the Cumberland

Army of the Cumberland

The Army of the Cumberland was one of the principal Union armies in the Western Theater during the American Civil War. It was originally known as the Army of the Ohio.-History:...

. Opposing him was the Confederate Army of Tennessee

Army of Tennessee

The Army of Tennessee was the principal Confederate army operating between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River during the American Civil War. It was formed in late 1862 and fought until the end of the war in 1865, participating in most of the significant battles in the Western Theater...

, commanded by Joseph E. Johnston. Sherman outnumbered Johnston 98,000 to 50,000, but his ranks were depleted by many furloughed soldiers, and Johnston received 15,000 reinforcements from Alabama

Alabama

Alabama is a state located in the southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Tennessee to the north, Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gulf of Mexico to the south, and Mississippi to the west. Alabama ranks 30th in total land area and ranks second in the size of its inland...

in April.

The campaign opened with several battles in May and June 1864 as Sherman pressed Johnston southeast through mountainous terrain. Sherman avoided frontal assaults against most of Johnston's positions, instead maneuvering in flanking marches around the Confederate defenses. When Sherman flanked the defensive lines (almost exclusively around Johnston's left flank), Johnston would retreat to another prepared position. The Battle of Kennesaw Mountain

Battle of Kennesaw Mountain

The Battle of Kennesaw Mountain was fought on June 27, 1864, during the Atlanta Campaign of the American Civil War. It was the most significant frontal assault launched by Union Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman against the Confederate Army of Tennessee under Gen. Joseph E...

(June 27) was a notable exception, in which Sherman attempted a frontal assault, against the advice of his subordinates, and suffered significant losses, losing 7,000 men versus 700 for Johnston. Both armies took advantage of the railroads as supply lines, with Johnston shortening his supply lines as he drew closer to Atlanta, and Sherman lengthening his own. However, Davis was becoming frustrated with Johnston, who he viewed was needlessly losing territory and was refusing to counterattack or even discuss his plans with Davis.

Just before the Battle of Peachtree Creek

Battle of Peachtree Creek

The Battle of Peachtree Creek was fought in Georgia on July 20, 1864, as part of the Atlanta Campaign in the American Civil War. It was the first major attack by Lt. Gen. John B. Hood since taking command of the Confederate Army of Tennessee. The attack was against Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman's...

(July 20) in the outskirts of Atlanta, Jefferson Davis lost patience with Johnston's strategy and, fearing that Johnston would give up Atlanta without a battle, replaced him with the more aggressive Lt. Gen. John Bell Hood

John Bell Hood

John Bell Hood was a Confederate general during the American Civil War. Hood had a reputation for bravery and aggressiveness that sometimes bordered on recklessness...

. Over the next six weeks, Hood would repeatedly attempt to attack a portion of Sherman's force which seemed isolated from the main body; each attack failed, often with heavy casualties for the Confederate army. Sherman eventually cut Hood's supply lines from the south. Knowing that he was trapped, Hood evacuated Atlanta on the night of September 1, burning military supplies and installations, causing a great conflagration in the city.

Coincident with Sherman's triumph in Atlanta, Admiral David Farragut

David Farragut

David Glasgow Farragut was a flag officer of the United States Navy during the American Civil War. He was the first rear admiral, vice admiral, and admiral in the United States Navy. He is remembered in popular culture for his order at the Battle of Mobile Bay, usually paraphrased: "Damn the...

won the decisive naval Battle of Mobile Bay

Battle of Mobile Bay

The Battle of Mobile Bay of August 5, 1864, was an engagement of the American Civil War in which a Federal fleet commanded by Rear Adm. David G. Farragut, assisted by a contingent of soldiers, attacked a smaller Confederate fleet led by Adm...

on August 24. Steaming past the forts guarding the mouth of the bay, Farragut engaged and forced the surrender of the Confederate fleet defending the city, capturing Admiral Franklin Buchanan

Franklin Buchanan

Franklin Buchanan was an officer in the United States Navy who became an admiral in the Confederate Navy during the American Civil War, and commanded the ironclad CSS Virginia.-Early life:...

. The city itself, long a desired target of Grant's, would remain in Confederate hands until 1865, but the last seaport east of the Mississippi on the Gulf Coast was closed, further tightening the Union blockade

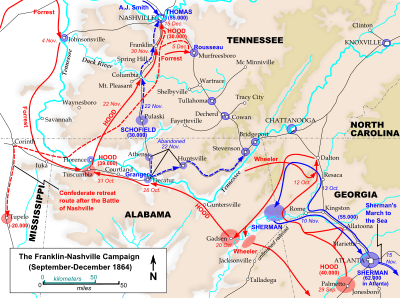

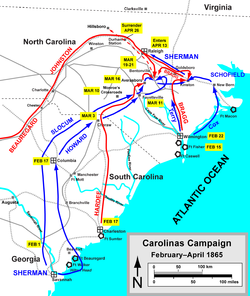

Union blockade