Archimedes' use of infinitesimals

Encyclopedia

The Method of Mechanical Theorems is a work by Archimedes

which contains the first attested explicit use of infinitesimal

s. The work was originally thought to be lost, but was rediscovered in the celebrated Archimedes Palimpsest

. The palimpsest includes Archimedes' account of the "mechanical method", so called because it relies on the law of the lever, which was first demonstrated by Archimedes, and of the center of gravity

, which he had found for many special cases.

Archimedes did not admit infinitesimals as part of rigorous mathematics, and therefore did not publish his method in the formal treatises that contain the results. In these treatises, he proves the same theorems by exhaustion, finding rigorous upper and lower bounds which both converge to the answer required. Nevertheless, the mechanical method was what he used to discover the relations for which he later gave rigorous proofs.

which is 1/3 by elementary integral calculus.

To find this integral, consider balancing a triangle with the parabola. The triangle is the region in the x-y plane between the x-axis and the line y = x as x varies from 0 to 1. The parabola is the region in the x-y plane between the x-axis and y = x2, also as x varies from 0 to 1.

Slice the triangle and parabola into vertical slices, one for each value of x. Imagine that the x-axis is a lever, with a fulcrum at x=0. By the law of the lever—the mass times the distance to the fulcrum must be equal in order for two things to balance. The mass of the slice of the triangle at position x is equal to its height, to x, and it is at a distance x from the fulcrum, so that it will balance the corresponding slice of the parabola, of height x2, if it is placed at x=−1, at a distance of 1 on the other side of the fulcrum.

Since each slice balances, the whole parabola balances the whole triangle. This means that if the parabola is hung by a hook from the point x = −1, it will balance the triangle sitting between x = 0 and x = 1.

The center of mass of a triangle can be easily found by the following method, also due to Archimedes. If a median line

is drawn from any one of the vertices of a triangle to the opposite edge E, the triangle will balance on the median, considered as a fulcrum. The reason is that if the triangle is divided into infinitesimal line segments parallel to E, each segment has equal length on opposite sides of the median, so balance follows by symmetry. This argument can be easily made rigorous by exhaustion by using little rectangles instead of infinitesimal lines, and this is what Archimedes does in On the Equilibrium of Planes.

So the center of mass of a triangle must be at the intersection point of the medians. For the triangle in question, one median is the line y = x/2, while a second median is the line y = 1 − x. The intersection of the two medians is at the point x = 2/3, so that the total mass of the triangle can be thought of as pushing down on this point. The total area of the triangle is 1/2, so the total torque exerted by the triangle is 1/2 times the distance to the center of mass, 2/3, which comes out to 1/3. The mass of the parabola, the area of the parabola, must then be 1/3.

This type of method can be used to find the area of an arbitrary section of a parabola, and similar arguments can be used to find the integral of any power of x, although higher powers become complicated without algebra. Archimedes only went as far as the integral of x3, which he used to find the center of mass of a hemisphere, and in other work, the center of mass of a parabola.

.

The points A and B are on the curve. The line AC is parallel to the axis of the parabola. The line BC is tangent

The points A and B are on the curve. The line AC is parallel to the axis of the parabola. The line BC is tangent

to the parabola.

The first proposition states:

at any x between 0 and 2 is given by the following formula:

at any x between 0 and 2 is given by the following formula:

The mass of this cross section, for purposes of balancing on a lever, is proportional to the area:

Archimedes then considered rotating the region between y = 0 and y = x on the x-y plane around the x-axis, to form a cone. The cross section of this cone is a circle of radius

and the area of this cross section is

So if slices of the cone and the sphere both are to be weighed together, the combined cross-sectional area is:

If the two slices are placed together at distance 1 from the fulcrum, their total weight would be exactly balanced by a circle of area at a distance x from the fulcrum on the other side. This means that the cone and the sphere together will balance a cylinder on the other side.

at a distance x from the fulcrum on the other side. This means that the cone and the sphere together will balance a cylinder on the other side.

In order for the slices to balance in this argument, each slice of the sphere and the cone should be hung at a distance 1 from the fulcrum, so that the torque will be just proportional to the area. But the corresponding slice of the cylinder should be hung at position x on the other side. As x ranges from 0 to 2, the cylinder will have a center of gravity a distance 1 from the fulcrum, so all the weight of the cylinder can be considered to be at position 1. The condition of balance ensures that the volume of the cone plus the volume of the sphere is equal to the volume of the cylinder.

The volume of the cylinder is the cross section area, times the height, which is 2, or

times the height, which is 2, or  . Archimedes could also find the volume of the cone using the mechanical method, since, in modern terms, the integral involved is exactly the same as the one for area of the parabola. The volume of the cone is 1/3 its base area times the height. The base of the cone is a circle of radius 2, with area

. Archimedes could also find the volume of the cone using the mechanical method, since, in modern terms, the integral involved is exactly the same as the one for area of the parabola. The volume of the cone is 1/3 its base area times the height. The base of the cone is a circle of radius 2, with area  , while the height is 2, so the area is

, while the height is 2, so the area is  . Subtracting the volume of the cone from the volume of the cylinder gives the volume of the sphere:

. Subtracting the volume of the cone from the volume of the cylinder gives the volume of the sphere:

The dependence of the volume of the sphere on the radius is obvious from scaling, although that also was not trivial to make rigorous back then. The method then gives the familiar formula for the volume of a sphere. By scaling the dimensions linearly Archimedes easily extended the volume result to spheroids.

Archimedes argument is nearly identical to the argument above, but his cylinder had a bigger radius, so that the cone and the cylinder hung at a greater distance from the fulcrum. He considered this argument to be his greatest achievement, requesting that the accompanying figure of the balanced sphere, cone, and cylinder be engraved upon his tombstone.

Archimedes states that the total volume of the sphere is equal to the volume of a cone whose base has the same surface area as the sphere and whose height is the radius. There are no details given for the argument, but the obvious reason is that the cone can be divided into infinitesimal cones by splitting the base area up, and the each cone makes a contribution according to its base area, just the same as in the sphere.

Let the surface of the sphere be S. The volume of the cone with area S and height r is , which must equal the volume of the sphere:

, which must equal the volume of the sphere:  . Therefore the surface area of the sphere must be

. Therefore the surface area of the sphere must be  , or "four times its largest circle". Archimedes proves this rigorously in On the Sphere and Cylinder

, or "four times its largest circle". Archimedes proves this rigorously in On the Sphere and Cylinder

.

Archimedes emphasizes this in the beginning of the treatise, and invites the reader to try to reproduce the results by some other method. Unlike the other examples, the volume of these shapes is not rigorously computed in any of his other works. From fragments in the palimpsest, it appears that Archimedes did inscribe and circumscribe shapes to prove rigorous bounds for the volume, although the details have not been preserved.

The two shapes he considers are the intersection of two cylinders at right angles, which is the region of (x, y, z) obeying:

and the circular prism, which is the region obeying:

Both problems have a slicing which produces an easy integral for the mechanical method. For the circular prism, cut up the x-axis into slices. The region in the y-z plane at any x is the interior of a right triangle of side length whose area is

whose area is  , so that the total volume is:

, so that the total volume is:

which can be easily rectified using the mechanical method. Adding to each triangular section a section of a triangular pyramid with area balances a prism whose cross section is constant.

balances a prism whose cross section is constant.

For the intersection of two cylinders, the slicing is lost in the manuscript, but it can be reconstructed in an obvious way in parallel to the rest of the document: if the x-z plane is the slice direction, the equations for the cylinder give that while

while  , which defines a region which is a square in the x-z plane of side length

, which defines a region which is a square in the x-z plane of side length  , so that the total volume is:

, so that the total volume is:

And this is the same integral as for the previous example.

is located 5/8 of the way from the pole to the center of the sphere. This problem is notable, because it is evaluating a cubic integral.

Archimedes

Archimedes of Syracuse was a Greek mathematician, physicist, engineer, inventor, and astronomer. Although few details of his life are known, he is regarded as one of the leading scientists in classical antiquity. Among his advances in physics are the foundations of hydrostatics, statics and an...

which contains the first attested explicit use of infinitesimal

Infinitesimal

Infinitesimals have been used to express the idea of objects so small that there is no way to see them or to measure them. The word infinitesimal comes from a 17th century Modern Latin coinage infinitesimus, which originally referred to the "infinite-th" item in a series.In common speech, an...

s. The work was originally thought to be lost, but was rediscovered in the celebrated Archimedes Palimpsest

Archimedes Palimpsest

The Archimedes Palimpsest is a palimpsest on parchment in the form of a codex. It originally was a copy of an otherwise unknown work of the ancient mathematician, physicist, and engineer Archimedes of Syracuse and other authors, which was overwritten with a religious text.Archimedes lived in the...

. The palimpsest includes Archimedes' account of the "mechanical method", so called because it relies on the law of the lever, which was first demonstrated by Archimedes, and of the center of gravity

Center of gravity

In physics, a center of gravity of a material body is a point that may be used for a summary description of gravitational interactions. In a uniform gravitational field, the center of mass serves as the center of gravity...

, which he had found for many special cases.

Archimedes did not admit infinitesimals as part of rigorous mathematics, and therefore did not publish his method in the formal treatises that contain the results. In these treatises, he proves the same theorems by exhaustion, finding rigorous upper and lower bounds which both converge to the answer required. Nevertheless, the mechanical method was what he used to discover the relations for which he later gave rigorous proofs.

Area of a parabola

To explain Archimedes' method today, it is convenient to make use of a little bit of Cartesian geometry, although this of course was unavailable at the time. His idea is to use the law of the lever to determine the areas of figures from the known center of mass of other figures. The simplest example in modern language is the area of the parabola. Archimedes uses a more elegant method, but in Cartesian language, his method is calculating the integralwhich is 1/3 by elementary integral calculus.

To find this integral, consider balancing a triangle with the parabola. The triangle is the region in the x-y plane between the x-axis and the line y = x as x varies from 0 to 1. The parabola is the region in the x-y plane between the x-axis and y = x2, also as x varies from 0 to 1.

Slice the triangle and parabola into vertical slices, one for each value of x. Imagine that the x-axis is a lever, with a fulcrum at x=0. By the law of the lever—the mass times the distance to the fulcrum must be equal in order for two things to balance. The mass of the slice of the triangle at position x is equal to its height, to x, and it is at a distance x from the fulcrum, so that it will balance the corresponding slice of the parabola, of height x2, if it is placed at x=−1, at a distance of 1 on the other side of the fulcrum.

Since each slice balances, the whole parabola balances the whole triangle. This means that if the parabola is hung by a hook from the point x = −1, it will balance the triangle sitting between x = 0 and x = 1.

The center of mass of a triangle can be easily found by the following method, also due to Archimedes. If a median line

Median (geometry)

In geometry, a median of a triangle is a line segment joining a vertex to the midpoint of the opposing side. Every triangle has exactly three medians; one running from each vertex to the opposite side...

is drawn from any one of the vertices of a triangle to the opposite edge E, the triangle will balance on the median, considered as a fulcrum. The reason is that if the triangle is divided into infinitesimal line segments parallel to E, each segment has equal length on opposite sides of the median, so balance follows by symmetry. This argument can be easily made rigorous by exhaustion by using little rectangles instead of infinitesimal lines, and this is what Archimedes does in On the Equilibrium of Planes.

So the center of mass of a triangle must be at the intersection point of the medians. For the triangle in question, one median is the line y = x/2, while a second median is the line y = 1 − x. The intersection of the two medians is at the point x = 2/3, so that the total mass of the triangle can be thought of as pushing down on this point. The total area of the triangle is 1/2, so the total torque exerted by the triangle is 1/2 times the distance to the center of mass, 2/3, which comes out to 1/3. The mass of the parabola, the area of the parabola, must then be 1/3.

This type of method can be used to find the area of an arbitrary section of a parabola, and similar arguments can be used to find the integral of any power of x, although higher powers become complicated without algebra. Archimedes only went as far as the integral of x3, which he used to find the center of mass of a hemisphere, and in other work, the center of mass of a parabola.

First proposition in the palimpsest

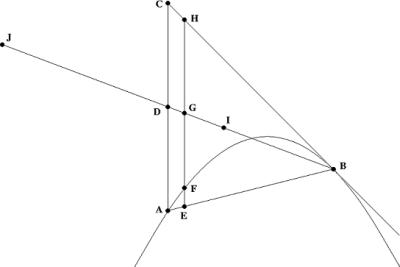

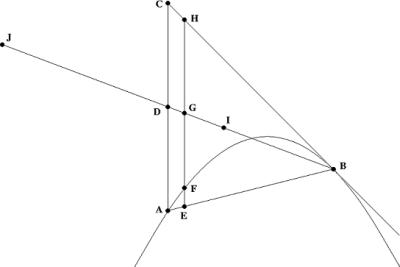

The curve in this figure is a parabolaParabola

In mathematics, the parabola is a conic section, the intersection of a right circular conical surface and a plane parallel to a generating straight line of that surface...

.

Tangent

In geometry, the tangent line to a plane curve at a given point is the straight line that "just touches" the curve at that point. More precisely, a straight line is said to be a tangent of a curve at a point on the curve if the line passes through the point on the curve and has slope where f...

to the parabola.

The first proposition states:

- The area of the triangle ABC is exactly three times the area bounded by the parabola and the secant line AB.

- Proof: Let D be the midpoint of AC. The point D is the fulcrum of a lever, which is the line JB. The points J and B are at equal distances from the fulcrum. As Archimedes had shown, the center of gravity of the interior of the triangle is at a point I on the "lever" so located that DI:DB = 1:3. Therefore, it suffices to show that if the whole weight of the interior of the triangle rests at I, and the whole weight of the section of the parabola at J, the lever is in equilibrium. If the whole weight of the triangle rests at I, it exerts the same torque on the lever as if the infinitely small weight of every cross-section EH parallel to the axis of the parabola rests at the point G where it intersects the lever. Therefore, it suffices to show that if the weight of that cross-section rests at G and the weight of the cross-section EF of the section of the parabola rests at J, then the lever is in equilibrium. In other words, it suffices to show that EF:GD = EH:JD. That is equivalent to EF:DG = EH:DB. And that is equivalent to EF:EH = AE:AB. But that is just the equation of the parabola. Q.E.D.Q.E.D.Q.E.D. is an initialism of the Latin phrase , which translates as "which was to be demonstrated". The phrase is traditionally placed in its abbreviated form at the end of a mathematical proof or philosophical argument when what was specified in the enunciation — and in the setting-out —...

Volume of a sphere

Again, to illuminate the mechanical method, it is convenient to use a little bit of coordinate geometry. If a sphere of radius 1 is placed at x = 1, the cross section at any x between 0 and 2 is given by the following formula:

at any x between 0 and 2 is given by the following formula:

The mass of this cross section, for purposes of balancing on a lever, is proportional to the area:

Archimedes then considered rotating the region between y = 0 and y = x on the x-y plane around the x-axis, to form a cone. The cross section of this cone is a circle of radius

and the area of this cross section is

So if slices of the cone and the sphere both are to be weighed together, the combined cross-sectional area is:

If the two slices are placed together at distance 1 from the fulcrum, their total weight would be exactly balanced by a circle of area

at a distance x from the fulcrum on the other side. This means that the cone and the sphere together will balance a cylinder on the other side.

at a distance x from the fulcrum on the other side. This means that the cone and the sphere together will balance a cylinder on the other side.In order for the slices to balance in this argument, each slice of the sphere and the cone should be hung at a distance 1 from the fulcrum, so that the torque will be just proportional to the area. But the corresponding slice of the cylinder should be hung at position x on the other side. As x ranges from 0 to 2, the cylinder will have a center of gravity a distance 1 from the fulcrum, so all the weight of the cylinder can be considered to be at position 1. The condition of balance ensures that the volume of the cone plus the volume of the sphere is equal to the volume of the cylinder.

The volume of the cylinder is the cross section area,

times the height, which is 2, or

times the height, which is 2, or  . Archimedes could also find the volume of the cone using the mechanical method, since, in modern terms, the integral involved is exactly the same as the one for area of the parabola. The volume of the cone is 1/3 its base area times the height. The base of the cone is a circle of radius 2, with area

. Archimedes could also find the volume of the cone using the mechanical method, since, in modern terms, the integral involved is exactly the same as the one for area of the parabola. The volume of the cone is 1/3 its base area times the height. The base of the cone is a circle of radius 2, with area  , while the height is 2, so the area is

, while the height is 2, so the area is  . Subtracting the volume of the cone from the volume of the cylinder gives the volume of the sphere:

. Subtracting the volume of the cone from the volume of the cylinder gives the volume of the sphere:The dependence of the volume of the sphere on the radius is obvious from scaling, although that also was not trivial to make rigorous back then. The method then gives the familiar formula for the volume of a sphere. By scaling the dimensions linearly Archimedes easily extended the volume result to spheroids.

Archimedes argument is nearly identical to the argument above, but his cylinder had a bigger radius, so that the cone and the cylinder hung at a greater distance from the fulcrum. He considered this argument to be his greatest achievement, requesting that the accompanying figure of the balanced sphere, cone, and cylinder be engraved upon his tombstone.

Surface area of a sphere

To find the surface area of the sphere, Archimedes argued that just as the area of the circle could be thought of as infinitely many infinitesimal right triangles going around the circumference (see Measurement of the Circle), the volume of the sphere could be thought of as divided into many cones with height equal to the radius and base on the surface. The cones all have the same height, so their volume is 1/3 the base area times the height.Archimedes states that the total volume of the sphere is equal to the volume of a cone whose base has the same surface area as the sphere and whose height is the radius. There are no details given for the argument, but the obvious reason is that the cone can be divided into infinitesimal cones by splitting the base area up, and the each cone makes a contribution according to its base area, just the same as in the sphere.

Let the surface of the sphere be S. The volume of the cone with area S and height r is

, which must equal the volume of the sphere:

, which must equal the volume of the sphere:  . Therefore the surface area of the sphere must be

. Therefore the surface area of the sphere must be  , or "four times its largest circle". Archimedes proves this rigorously in On the Sphere and Cylinder

, or "four times its largest circle". Archimedes proves this rigorously in On the Sphere and CylinderOn the Sphere and Cylinder

On the Sphere and Cylinder is a work that was published by Archimedes in two volumes c. 225 BC. It most notably details how to find the surface area of a sphere and the volume of the contained ball and the analogous values for a cylinder, and was the first to do so.-Contents:The principal formulae...

.

Curvilinear shapes with rational volumes

One of the remarkable things about the Method is that Archimedes finds two shapes defined by sections of cylinders, whose volume does not involve π, despite the shapes having curvilinear boundaries. This is a central point of the investigation—certain curvilinear shapes could be rectified by ruler and compass, so that there are nontrivial rational relations between the volumes defined by the intersections of geometrical solids.Archimedes emphasizes this in the beginning of the treatise, and invites the reader to try to reproduce the results by some other method. Unlike the other examples, the volume of these shapes is not rigorously computed in any of his other works. From fragments in the palimpsest, it appears that Archimedes did inscribe and circumscribe shapes to prove rigorous bounds for the volume, although the details have not been preserved.

The two shapes he considers are the intersection of two cylinders at right angles, which is the region of (x, y, z) obeying:

-

- (2Cyl)

- (2Cyl)

and the circular prism, which is the region obeying:

-

- (CirP)

- (CirP)

Both problems have a slicing which produces an easy integral for the mechanical method. For the circular prism, cut up the x-axis into slices. The region in the y-z plane at any x is the interior of a right triangle of side length

whose area is

whose area is  , so that the total volume is:

, so that the total volume is:-

- (CirP)

- (CirP)

which can be easily rectified using the mechanical method. Adding to each triangular section a section of a triangular pyramid with area

balances a prism whose cross section is constant.

balances a prism whose cross section is constant.For the intersection of two cylinders, the slicing is lost in the manuscript, but it can be reconstructed in an obvious way in parallel to the rest of the document: if the x-z plane is the slice direction, the equations for the cylinder give that

while

while  , which defines a region which is a square in the x-z plane of side length

, which defines a region which is a square in the x-z plane of side length  , so that the total volume is:

, so that the total volume is:-

- (2Cyl)

- (2Cyl)

And this is the same integral as for the previous example.

Other propositions in the palimpsest

A series of propositions of geometry are proved in the palimpsest by similar arguments. One theorem is that the location of a center of gravity of a hemisphereHemisphere

Hemisphere may refer to:*Half of a sphereAs half of the Earth:*Any half of the Earth, see Hemispheres of the Earth, see:...

is located 5/8 of the way from the pole to the center of the sphere. This problem is notable, because it is evaluating a cubic integral.