Austen Henry Layard

Encyclopedia

Sir Austen Henry Layard GCB

, PC (icon; 5 March 1817 – 5 July 1894) was a British

traveller, archaeologist, cuneiformist, art historian, draughtsman, collector, author, politician and diplomat, best known as the excavator of Nimrud

.

, France

, to a family of Huguenot

descent. His father, Henry Peter John Layard, of the Ceylon Civil Service

, was the son of Charles Peter Layard, dean of Bristol, and grandson of Daniel Peter Layard, the physician. Through his mother, a daughter of Nathaniel Austen, banker, of Ramsgate, he was partly Spanish

descent. His uncle was Benjamin Austen, a London

solicitor

and close friend of Benjamin Disraeli

in the 1820s and 1830s. His brother was the ornithologist

Edgar Leopold Layard

.

, where he received part of his schooling, and acquired a taste for the fine arts and a love of travel; but he was at school also in England

, France

and Switzerland

. After spending nearly six years in the office of his uncle, Benjamin Layard, he was tempted to leave England for Sri Lanka

(Ceylon) by the prospect of obtaining an appointment in the civil service, and he started in 1839 with the intention of making an overland journey across Asia.

After wandering for many months, chiefly in Persia, and having abandoned his intention of proceeding to Ceylon, he returned in 1842 to Constantinople

, where he made the acquaintance of Sir Stratford Canning

, the British Ambassador, who employed him in various unofficial diplomatic missions in European Turkey. In 1845, encouraged and assisted by Canning, Layard left Constantinople to make those explorations among the ruins of Assyria with which his name is chiefly associated. This expedition was in fulfilment of a design which he had formed, when, during his former travels in the East, his curiosity had been greatly excited by the ruins of Nimrud

on the Tigris

, and by the great mound of Kuyunjik, near Mosul

, already partly excavated by Paul-Émile Botta

.

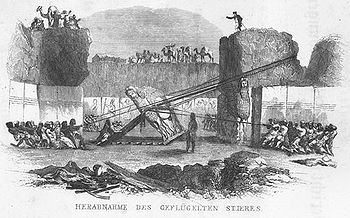

, and investigating the condition of various peoples, until 1847; and, returning to England in 1848, published Nineveh and its Remains: with an Account of a Visit to tile Chaldaean Christians of Kurdistan, and the Yezidis, or Devil-worshippers; and an Inquiry into the Manners and Arts of the Ancient Assyrians (2 vols., 1848–1849).

To illustrate the antiquities described in this work he published a large folio volume of Illustrations of the Monuments of Nineveh (1849). After spending a few months in England, and receiving the degree of D.C.L. from the University of Oxford

, Layard returned to Constantinople as attaché to the British embassy, and, in August 1849, started on a second expedition, in the course of which he extended his investigations to the ruins of Babylon

and the mounds of southern Mesopotamia

. He is credited with discovering the Library of Ashurbanipal

during this period. His record of this expedition, Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon, which was illustrated by another folio volume, called A Second Series of the Monuments of Nineveh, was published in 1853. During these expeditions, often in circumstances of great difficulty, Layard despatched to England the splendid specimens which now form the greater part of the collection of Assyrian antiquities in the British Museum.

Apart from the archaeological value of his work in identifying Kuyunjik as the site of Nineveh, and in providing a great mass of materials for scholars to work upon, these two books of Layard's were among the best written books of travel in the language.

Layard was an important member of the Arundel Society

. During 1866 Layard founded "Compagnia Venezia Murano" and opened a venetian glass showroom in London at 431 Oxford Street.

Today Pauly & C. - Compagnia Venezia Murano

is one of most important brand of venetian art glass production. In 1866 he was appointed a trustee of the British Museum.

, Buckinghamshire

in 1852, he was for a few weeks Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs, but afterwards freely criticized the government, especially in connection with army administration. He was present in the Crimea

during the war

, and was a member of the committee appointed to inquire into the conduct of the expedition. In 1855 he refused from Lord Palmerston

an office not connected with foreign affairs, was elected lord rector of Aberdeen university

, and on June 15 moved a resolution in the House of Commons (defeated by a large majority) declaring that in public appointments merit had been sacrificed to private influence and an adherence to routine. After being defeated at Aylesbury in 1857, he visited India to investigate the causes of the Mutiny. He unsuccessfully contested York in 1859, but was elected for Southwark

in 1860, and from 1861 to 1866 was Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs in the successive administrations of Lord Palmerston and Lord John Russell. After the Liberals returned to office in 1868 under William Ewart Gladstone

, Layard was made First Commissioner of Works

and sworn of the Privy Council.

Layard resigned from office in 1869, on being sent as envoy extraordinary to Madrid. In 1877 he was appointed by Lord Beaconsfield Ambassador at Constantinople, where he remained until Gladstone's return to power in 1880, when he finally retired from public life. In 1878, on the occasion of the Berlin Congress, he was appointed a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath

Layard resigned from office in 1869, on being sent as envoy extraordinary to Madrid. In 1877 he was appointed by Lord Beaconsfield Ambassador at Constantinople, where he remained until Gladstone's return to power in 1880, when he finally retired from public life. In 1878, on the occasion of the Berlin Congress, he was appointed a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath

.

, where he devoted much of his time to collecting pictures of the Venetian school, and to writing on Italian art. On this subject he was a disciple of his friend Giovanni Morelli

, whose views he embodied in his revision of Franz Kugler

's Handbook of Painting, Italian Schools (1887). He wrote also an introduction to Constance Jocelyn Ffoulkes's translation of Morelli's Italian Painters (1892–1893), and edited that part of Murray's Handbook of Rome (1894) which deals with pictures. In 1887 he published, from notes taken at the time, a record of his first journey to the East, entitled Early Adventures in Persia, Susiana and Babylonia. An abbreviation of this work, which as a book of travel is even more delightful than its predecessors, was published in 1894, shortly after the author's death, with a brief introductory notice by Lord Aberdare. Layard also from time to time contributed papers to various learned societies, including the Huguenot Society, of which he was first president. He died in London.

Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate mediæval ceremony for creating a knight, which involved bathing as one of its elements. The knights so created were known as Knights of the Bath...

, PC (icon; 5 March 1817 – 5 July 1894) was a British

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

traveller, archaeologist, cuneiformist, art historian, draughtsman, collector, author, politician and diplomat, best known as the excavator of Nimrud

Nimrud

Nimrud is an ancient Assyrian city located south of Nineveh on the river Tigris in modern Ninawa Governorate Iraq. In ancient times the city was called Kalḫu. The Arabs called the city Nimrud after the Biblical Nimrod, a legendary hunting hero .The city covered an area of around . Ruins of the city...

.

Family

Layard was born in ParisParis

Paris is the capital and largest city in France, situated on the river Seine, in northern France, at the heart of the Île-de-France region...

, France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

, to a family of Huguenot

Huguenot

The Huguenots were members of the Protestant Reformed Church of France during the 16th and 17th centuries. Since the 17th century, people who formerly would have been called Huguenots have instead simply been called French Protestants, a title suggested by their German co-religionists, the...

descent. His father, Henry Peter John Layard, of the Ceylon Civil Service

Ceylon Civil Service

The Ceylon Civil Service, popularly known by its acronym CCS, originated as the elite civil service of the Government of Ceylon under British colonial rule in 1833 and carried on after independence, until May 1, 1963 when it was abolished and the much larger Ceylon Administrative Service was...

, was the son of Charles Peter Layard, dean of Bristol, and grandson of Daniel Peter Layard, the physician. Through his mother, a daughter of Nathaniel Austen, banker, of Ramsgate, he was partly Spanish

Spain

Spain , officially the Kingdom of Spain languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Spain's official name is as follows:;;;;;;), is a country and member state of the European Union located in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula...

descent. His uncle was Benjamin Austen, a London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

solicitor

Solicitor

Solicitors are lawyers who traditionally deal with any legal matter including conducting proceedings in courts. In the United Kingdom, a few Australian states and the Republic of Ireland, the legal profession is split between solicitors and barristers , and a lawyer will usually only hold one title...

and close friend of Benjamin Disraeli

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield, KG, PC, FRS, was a British Prime Minister, parliamentarian, Conservative statesman and literary figure. Starting from comparatively humble origins, he served in government for three decades, twice as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom...

in the 1820s and 1830s. His brother was the ornithologist

Ornithology

Ornithology is a branch of zoology that concerns the study of birds. Several aspects of ornithology differ from related disciplines, due partly to the high visibility and the aesthetic appeal of birds...

Edgar Leopold Layard

Edgar Leopold Layard

Edgar Leopold Layard CMG, FZS, MBOU was a British naturalist mainly interested in ornithology. Born in Florence, Italy, to a family of Huguenot descent, he was the sixth son of Henry Peter John Layard of the Ceylon Civil Service with his wife Marianne,...

.

Early life

Much of Layard's boyhood was spent in ItalyItaly

Italy , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

, where he received part of his schooling, and acquired a taste for the fine arts and a love of travel; but he was at school also in England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

, France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

and Switzerland

Switzerland

Switzerland name of one of the Swiss cantons. ; ; ; or ), in its full name the Swiss Confederation , is a federal republic consisting of 26 cantons, with Bern as the seat of the federal authorities. The country is situated in Western Europe,Or Central Europe depending on the definition....

. After spending nearly six years in the office of his uncle, Benjamin Layard, he was tempted to leave England for Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka, officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka is a country off the southern coast of the Indian subcontinent. Known until 1972 as Ceylon , Sri Lanka is an island surrounded by the Indian Ocean, the Gulf of Mannar and the Palk Strait, and lies in the vicinity of India and the...

(Ceylon) by the prospect of obtaining an appointment in the civil service, and he started in 1839 with the intention of making an overland journey across Asia.

After wandering for many months, chiefly in Persia, and having abandoned his intention of proceeding to Ceylon, he returned in 1842 to Constantinople

Constantinople

Constantinople was the capital of the Roman, Eastern Roman, Byzantine, Latin, and Ottoman Empires. Throughout most of the Middle Ages, Constantinople was Europe's largest and wealthiest city.-Names:...

, where he made the acquaintance of Sir Stratford Canning

Stratford Canning, 1st Viscount Stratford de Redcliffe

Stratford Canning, 1st Viscount Stratford de Redcliffe KG GCB PC , was a British diplomat and politician, best known as the longtime British Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire...

, the British Ambassador, who employed him in various unofficial diplomatic missions in European Turkey. In 1845, encouraged and assisted by Canning, Layard left Constantinople to make those explorations among the ruins of Assyria with which his name is chiefly associated. This expedition was in fulfilment of a design which he had formed, when, during his former travels in the East, his curiosity had been greatly excited by the ruins of Nimrud

Nimrud

Nimrud is an ancient Assyrian city located south of Nineveh on the river Tigris in modern Ninawa Governorate Iraq. In ancient times the city was called Kalḫu. The Arabs called the city Nimrud after the Biblical Nimrod, a legendary hunting hero .The city covered an area of around . Ruins of the city...

on the Tigris

Tigris

The Tigris River is the eastern member of the two great rivers that define Mesopotamia, the other being the Euphrates. The river flows south from the mountains of southeastern Turkey through Iraq.-Geography:...

, and by the great mound of Kuyunjik, near Mosul

Mosul

Mosul , is a city in northern Iraq and the capital of the Ninawa Governorate, some northwest of Baghdad. The original city stands on the west bank of the Tigris River, opposite the ancient Assyrian city of Nineveh on the east bank, but the metropolitan area has now grown to encompass substantial...

, already partly excavated by Paul-Émile Botta

Paul-Émile Botta

Paul-Émile Botta was a French scientist who served as Consul in Mosul from 1842.-Life:...

.

Excavations and the arts

Layard remained in the neighbourhood of Mosul, carrying on excavations at Kuyunjik and NimrudNimrud

Nimrud is an ancient Assyrian city located south of Nineveh on the river Tigris in modern Ninawa Governorate Iraq. In ancient times the city was called Kalḫu. The Arabs called the city Nimrud after the Biblical Nimrod, a legendary hunting hero .The city covered an area of around . Ruins of the city...

, and investigating the condition of various peoples, until 1847; and, returning to England in 1848, published Nineveh and its Remains: with an Account of a Visit to tile Chaldaean Christians of Kurdistan, and the Yezidis, or Devil-worshippers; and an Inquiry into the Manners and Arts of the Ancient Assyrians (2 vols., 1848–1849).

To illustrate the antiquities described in this work he published a large folio volume of Illustrations of the Monuments of Nineveh (1849). After spending a few months in England, and receiving the degree of D.C.L. from the University of Oxford

University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a university located in Oxford, United Kingdom. It is the second-oldest surviving university in the world and the oldest in the English-speaking world. Although its exact date of foundation is unclear, there is evidence of teaching as far back as 1096...

, Layard returned to Constantinople as attaché to the British embassy, and, in August 1849, started on a second expedition, in the course of which he extended his investigations to the ruins of Babylon

Babylon

Babylon was an Akkadian city-state of ancient Mesopotamia, the remains of which are found in present-day Al Hillah, Babil Province, Iraq, about 85 kilometers south of Baghdad...

and the mounds of southern Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a toponym for the area of the Tigris–Euphrates river system, largely corresponding to modern-day Iraq, northeastern Syria, southeastern Turkey and southwestern Iran.Widely considered to be the cradle of civilization, Bronze Age Mesopotamia included Sumer and the...

. He is credited with discovering the Library of Ashurbanipal

Library of Ashurbanipal

-External links:. In our time discussion programme. 45 minutes....

during this period. His record of this expedition, Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon, which was illustrated by another folio volume, called A Second Series of the Monuments of Nineveh, was published in 1853. During these expeditions, often in circumstances of great difficulty, Layard despatched to England the splendid specimens which now form the greater part of the collection of Assyrian antiquities in the British Museum.

Apart from the archaeological value of his work in identifying Kuyunjik as the site of Nineveh, and in providing a great mass of materials for scholars to work upon, these two books of Layard's were among the best written books of travel in the language.

Layard was an important member of the Arundel Society

Arundel Society

The Arundel Society was founded at London in 1849 and named after the Earl of Arundel, the famous collector of the Arundel Marbles and one of the first great English patrons and lovers of the arts...

. During 1866 Layard founded "Compagnia Venezia Murano" and opened a venetian glass showroom in London at 431 Oxford Street.

Today Pauly & C. - Compagnia Venezia Murano

Pauly & C. - Compagnia Venezia Murano

Pauly & C. - Compagnia Venezia Murano is a Venetian company that produces glass art, most notably Roman murrine, mosaics and chandeliers.The company was formed in 1919 by a merger of Pauly & C and the Compagnia di Venezia e Murano...

is one of most important brand of venetian art glass production. In 1866 he was appointed a trustee of the British Museum.

Political career

Layard now turned to politics. Elected as a Liberal member for AylesburyAylesbury (UK Parliament constituency)

Aylesbury is a parliamentary constituency represented in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom. The Conservative Party has held the seat since 1924, and held it at the 2010 general election with a 52.2% share of the vote.-Boundaries:...

, Buckinghamshire

Buckinghamshire

Buckinghamshire is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan home county in South East England. The county town is Aylesbury, the largest town in the ceremonial county is Milton Keynes and largest town in the non-metropolitan county is High Wycombe....

in 1852, he was for a few weeks Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs, but afterwards freely criticized the government, especially in connection with army administration. He was present in the Crimea

Crimea

Crimea , or the Autonomous Republic of Crimea , is a sub-national unit, an autonomous republic, of Ukraine. It is located on the northern coast of the Black Sea, occupying a peninsula of the same name...

during the war

Crimean War

The Crimean War was a conflict fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the French Empire, the British Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Sardinia. The war was part of a long-running contest between the major European powers for influence over territories of the declining...

, and was a member of the committee appointed to inquire into the conduct of the expedition. In 1855 he refused from Lord Palmerston

Henry Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston

Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston, KG, GCB, PC , known popularly as Lord Palmerston, was a British statesman who served twice as Prime Minister in the mid-19th century...

an office not connected with foreign affairs, was elected lord rector of Aberdeen university

University of Aberdeen

The University of Aberdeen, an ancient university founded in 1495, in Aberdeen, Scotland, is a British university. It is the third oldest university in Scotland, and the fifth oldest in the United Kingdom and wider English-speaking world...

, and on June 15 moved a resolution in the House of Commons (defeated by a large majority) declaring that in public appointments merit had been sacrificed to private influence and an adherence to routine. After being defeated at Aylesbury in 1857, he visited India to investigate the causes of the Mutiny. He unsuccessfully contested York in 1859, but was elected for Southwark

Southwark (UK Parliament constituency)

Southwark was a parliamentary constituency centred on the Southwark district of South London. It returned two Members of Parliament to the House of Commons of the English Parliament from 1295 to 1707, to the Parliament of Great Britain from 1707 to 1800, and to the Parliament of the United Kingdom...

in 1860, and from 1861 to 1866 was Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs in the successive administrations of Lord Palmerston and Lord John Russell. After the Liberals returned to office in 1868 under William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone FRS FSS was a British Liberal statesman. In a career lasting over sixty years, he served as Prime Minister four separate times , more than any other person. Gladstone was also Britain's oldest Prime Minister, 84 years old when he resigned for the last time...

, Layard was made First Commissioner of Works

First Commissioner of Works

The First Commissioner of Works and Public Buildings was a position within the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It took over some of the functions of the First Commissioner of Woods and Forests in 1851 when the portfolio of Crown holdings was divided into the public...

and sworn of the Privy Council.

Diplomatic career

Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate mediæval ceremony for creating a knight, which involved bathing as one of its elements. The knights so created were known as Knights of the Bath...

.

Retirement in Venice

Layard retired to VeniceVenice

Venice is a city in northern Italy which is renowned for the beauty of its setting, its architecture and its artworks. It is the capital of the Veneto region...

, where he devoted much of his time to collecting pictures of the Venetian school, and to writing on Italian art. On this subject he was a disciple of his friend Giovanni Morelli

Giovanni Morelli

Giovanni Morelli was an Italian art critic and political figure. As an art historian, he developed the "Morellian" technique of scholarship, identifying the characteristic "hands" of painters through scrutiny of diagnostic minor details that revealed artists' scarcely conscious shorthand and...

, whose views he embodied in his revision of Franz Kugler

Franz Kugler

Franz Theodor Kugler was a cultural administrator for the Prussian state and art historian...

's Handbook of Painting, Italian Schools (1887). He wrote also an introduction to Constance Jocelyn Ffoulkes's translation of Morelli's Italian Painters (1892–1893), and edited that part of Murray's Handbook of Rome (1894) which deals with pictures. In 1887 he published, from notes taken at the time, a record of his first journey to the East, entitled Early Adventures in Persia, Susiana and Babylonia. An abbreviation of this work, which as a book of travel is even more delightful than its predecessors, was published in 1894, shortly after the author's death, with a brief introductory notice by Lord Aberdare. Layard also from time to time contributed papers to various learned societies, including the Huguenot Society, of which he was first president. He died in London.

Publications

- Layard, A. H. (1848–49). Inquiry into the Painters and Arts of the Ancient Assyrians (vol. 1–2).

- Layard, A. H. (1849). Nineveh and its Remains. London: John MurrayJohn Murray (publisher)John Murray is an English publisher, renowned for the authors it has published in its history, including Jane Austen, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Lord Byron, Charles Lyell, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Herman Melville, and Charles Darwin...

. - Layard, A. H. (1849). Illustrations of the Monuments of Nineveh.

- Layard, A. H. (1849–53). The Monuments of Nineveh. London: John Murray.

- Layard, A. H. (1851). Inscriptions in the cuneiform character from Assyrian monuments. London: Harrison and sons.

- Layard, A. H. (1852). A Popular Account of Discoveries at Nineveh. London: John Murray.

- Layard, A. H. (1853). Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon. London: John Murray.

- Layard, A. H. (1853). A Second Series of the Monuments of Nineveh. London: John Murray

- Layard, A. H. (1854). The Ninevah Court in the Crystal Palace. London: John Murray.

- Layard, A. H. (1894). Early Adventures in Persia, Susiana, and Babylonia. London: John Murray.

- Layard, A. H. (1903). Autobiography and Letters from his childhood until his appointment as H.M. Ambassador at Madrid. (vol. 1–2) London: John Murray.

Further reading

- Brackman, Arnold C. The Luck of Nineveh: Archaeology's Great Adnventure. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1978 (hardcover, ISBN 0-07-007030-X); New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1981 (paperback, ISBN 0442282605).

- Jerman, B.R. The Young Disraeli. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1960.

- Kubie, Nora BenjaminNora Benjamin KubieNora Benjamin Kubie was an American writer, artist and amateur archaeologist.Born Eleanor Gottheil, she was the daughter of Muriel H. and Paul Gotteil, an executive with the Cunard Line in New York. She graduated from the Calhoun School in New York, delivering the valedictory speech in 1916...

. Road to Ninevah: the adventures and excavations of Sir Austen Henry Layard (1964; 1965 in the UK) - Larsen, Mogens T. The Conquest of Assyria. Routledge. 1996. ISBN 041514356X - the best modern account of Layard.

- Lloyd, Seton. Foundations in the Dust: The Story of Mesopotamian Exploration. London; New York: Thames & Hudson, 1981 (hardcover, ISBN 0-500-05038-4).

- Waterfield, Gordon. Layard of Nineveh. London: John Murray, 1963.

External links

- Nineveh and its Remains (vol. 1) (1849)

- Nineveh and its Remains (vol. 2) (1849)

- The Monuments of Nineveh (1849)

- The Monuments of Nineveh (1853)

- A Second Series of the Monuments of Nineveh (1853)

- The Monuments of Nineveh (1849–53)

- Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon (1853).

- A Popular Account of Discoveries at Nineveh (1854)

- The Ninevah Court in the Crystal Palace (1854)

- Autobiography and letters from his childhood until his appointment as H.M. Ambassador at Madrid (vol. 1) (1903)

- Autobiography and letters from his childhood until his appointment as H.M. Ambassador at Madrid (vol. 2) (1903)

- Official Site of Pauly & C. | CVM - Compagnia Venezia Murano