Benedict Arnold

Encyclopedia

Benedict Arnold V was a general during the American Revolutionary War

. He began the war in the Continental Army

but later defected

to the British Army

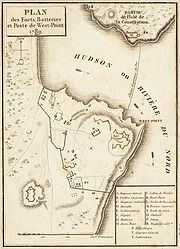

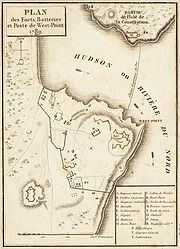

. While a general on the American side, he obtained command of the fort at West Point

, New York

, and plotted to surrender it to the British

forces. After the plot was exposed in September 1780, he was commissioned into the British Army as a brigadier general.

Born in Connecticut

, Arnold was a merchant operating ships on the Atlantic Ocean

when the war broke out in 1775. After joining the growing army outside Boston, he distinguished himself through acts of cunning and bravery. His actions included the Capture of Fort Ticonderoga

in 1775, defensive and delaying tactics despite losing the Battle of Valcour Island

on Lake Champlain

in 1776, the Battle of Ridgefield

, Connecticut (after which he was promoted to major general), operations in relief of the Siege of Fort Stanwix

, and key actions during the pivotal Battles of Saratoga in 1777, in which he suffered leg injuries that ended his combat career for several years.

Despite Arnold's successes, he was passed over for promotion by the Continental Congress

while other officers claimed credit for some of his accomplishments. Adversaries in military and political circles brought charges of corruption or other malfeasance, but most often he was acquitted in formal inquiries. Congress investigated his accounts and found he was indebted to Congress after spending much of his own money on the war effort. Frustrated and bitter, Arnold decided to change sides in 1779, and opened secret negotiations with the British. In July 1780, he sought and obtained command of West Point

in order to surrender it to the British. Arnold's scheme was exposed when American forces captured British Major John André

carrying papers that revealed the plot. Upon learning of André's capture, Arnold fled down the Hudson River

to the British sloop-of-war

Vulture

, narrowly avoiding capture by the forces of George Washington

, who had been alerted to the plot.

Arnold received a commission as a brigadier general in the British Army

, an annual pension of £360, and a lump sum of over £6,000. He led British forces on raids in Virginia

, and against New London and Groton, Connecticut

, before the war effectively ended with the American victory at Yorktown

. In the winter of 1782, Arnold moved to London

with his second wife, Margaret "Peggy" Shippen Arnold

. He was well received by King George III

and the Tories

but frowned upon by the Whigs. In 1787, he entered into mercantile business with his sons Richard and Henry in Saint John, New Brunswick

, but returned to London to settle permanently in 1791, where he died ten years later.

Because of the way he changed sides, his name quickly became a byword in the United States for treason

or betrayal. His conflicting legacy is recalled in the ambiguous nature of some of the memorials that have been placed in his honor.

, Connecticut

, on January 14, 1741. He was named after his great-grandfather Benedict Arnold

, an early governor of the Colony of Rhode Island, and his brother Benedict IV, who died in infancy. Only Benedict and his sister Hannah survived to adulthood; his other siblings succumbed to yellow fever

in childhood. Through his maternal grandmother, Arnold was a descendant of John Lothropp, an ancestor of at least four U.S. presidents

.

Arnold's father was a successful businessman, and the family moved in the upper levels of Norwich society. When he was ten, Arnold was enrolled in a private school in nearby Canterbury

, with the expectation that he would eventually attend Yale

. However, the deaths of his siblings two years later may have contributed to a decline in the family fortunes, since his father took up drinking. By the time he was fourteen, there was no money for private education. His father's alcoholism

and ill health kept him from training Arnold in the family mercantile business, but his mother's family connections secured an apprenticeship for Arnold with two of her cousins, brothers Daniel and Joshua Lathrop, who operated a successful apothecary

and general merchandise trade in Norwich. His apprenticeship with the Lathrops lasted seven years.

In 1755, Arnold, attracted by the sound of a drummer, attempted to enlist in the provincial militia

for service against the French

, but his mother refused permission. In 1757, when he was sixteen, he did enlist in the militia, which marched off toward Albany

and Lake George

. The French had besieged Fort William Henry, and their Indian allies had committed atrocities after their victory. Word of the siege's disastrous outcome led the company to turn around; Arnold served for 13 days. A commonly accepted story that Arnold deserted from militia service in 1758 is based on uncertain documentary evidence.

Arnold's mother, to whom he was very close, died in 1759. His father's alcoholism worsened after the death of his wife, and the youth took on the responsibility of supporting his father and younger sister. His father was arrested on several occasions for public drunkenness, was refused communion

by his church, and eventually died in 1761.

and bookseller in New Haven, Connecticut

. Arnold was hardworking and successful, and was able to rapidly expand his business. In 1763 he repaid money borrowed from the Lathrops, repurchased the family homestead that his father had sold when deeply in debt, and re-sold it a year later for a substantial profit. In 1764 he formed a partnership with Adam Babcock, another young New Haven merchant. Using the profits from the sale of his homestead they bought three trading ships and established a lucrative West Indies trade. During this time he brought his sister Hannah to New Haven and established her in his apothecary to manage the business in his absence. He traveled extensively in the course of his business, throughout New England

and from Quebec

to the West Indies, often in command of one of his own ships. On one of his voyages, Arnold fought a duel in Honduras

with a British sea captain who had called him a "damned Yankee, destitute of good manners or those of a gentleman". The captain was wounded after the first exchange of gunfire, and apologized after Arnold threatened to aim to kill on the second.

The Sugar Act

of 1764 and the Stamp Act

of 1765 severely curtailed mercantile trade

in the colonies. The latter act prompted Arnold to join the chorus of voices in opposition to those taxes, and also led to his entry into the Sons of Liberty

, a secret organization that was not afraid to use violence to oppose implementation of those and other unpopular Parliamentary measures. Arnold initially took no part in any public demonstrations but, like many merchants, continued to trade as if the Stamp Act did not exist, in effect becoming a smuggler in defiance of the act. Arnold also faced financial ruin, falling £16,000 in debt, with creditors spreading rumors of his insolvency to the point where he took legal action against them. On the night of January 28, 1767, Arnold and members of his crew, watched by a crowd of Sons, roughed up a man suspected of attempting to inform authorities of Arnold's smuggling. Arnold was convicted of a disorderly conduct charge and fined the relatively small amount of 50 shillings; publicity of the case and widespread sympathy for his view probably contributed to the light sentence.

On February 22, 1767, he married Margaret Mansfield, daughter of Samuel Mansfield, the sheriff of New Haven, an acquaintance that may have been made through the membership of both Mansfield and Arnold in the local Masonic Lodge

. Their first son, Benedict VI, was born the following year, and was followed by brothers Richard in 1769, and Henry in 1772. Margaret died early in the revolution, on June 19, 1775, while Arnold was at Fort Ticonderoga

following its capture. The household, even while she lived, was dominated by Arnold's sister Hannah. Arnold benefited from his relationship with Mansfield, who became a partner in his business and used his position as sheriff to shield Arnold from creditors.

Arnold was in the West Indies when the Boston Massacre

took place on March 5, 1770. He wrote he was "very much shocked" and wondered "good God, are the Americans all asleep and tamely giving up their liberties, or are they all turned philosophers, that they don't take immediate vengeance on such miscreants".

's militia, a position to which he was elected in March 1775. Following the outbreak of hostilities at Lexington and Concord

the following month, his company marched northeast to assist in the siege of Boston

that followed. Arnold proposed to the Massachusetts Committee of Safety

an action to seize Fort Ticonderoga

in New York

, which he knew was poorly defended. They issued him a colonel's commission on May 3, 1775, and he immediately rode off to the west, arriving at Castleton

in the disputed New Hampshire Grants

(present-day Vermont

) in time to participate with Ethan Allen

and his men in the capture of Fort Ticonderoga

. He followed up that action with a bold raid on Fort Saint-Jean

on the Richelieu River

north of Lake Champlain

. When a Connecticut militia force arrived at Ticonderoga in June, he had a dispute with its commander over control of the fort, and resigned his Massachusetts commission. He was on his way home from Ticonderoga when he learned that his wife died earlier in June.

When the Second Continental Congress

When the Second Continental Congress

authorized an invasion of Quebec

, in part on the urging of Arnold, he was passed over for command of the expedition. Arnold then went to Cambridge, Massachusetts

, and suggested to George Washington

a second expedition to attack Quebec City

via a wilderness route through present-day Maine

. This expedition, for which Arnold received a colonel's commission in the Continental Army

, left Cambridge in September 1775 with 1,100 men. After a difficult passage in which 300 men turned back and another 200 died en route, Arnold arrived before Quebec City in November. Joined by Richard Montgomery

's small army, he participated in the December 31 assault on Quebec City

in which Montgomery was killed and Arnold's leg was shattered. Rev. Samuel Spring

, his chaplain, carried him to the makeshift hospital at the Hotel Dieu. Arnold, who was promoted to brigadier general for his role in reaching Quebec, maintained an ineffectual siege of the city until he was replaced by Major General David Wooster

in April 1776.

Arnold then traveled to Montreal

, where he served as military commander of the city until forced to retreat by an advancing British army that had arrived at Quebec in May. He presided over the rear of the Continental Army during its retreat from Saint-Jean, where he was reported by James Wilkinson

to be the last person to leave before the British arrived. He then directed the construction of a fleet to defend Lake Champlain, which was defeated in the October 1776 Battle of Valcour Island

. His actions at Saint-Jean and Valcour Island played a notable role in delaying the British advance against Ticonderoga until 1777.

During these actions, Arnold made a number of friends and a larger number of enemies within the army power structure and in Congress. He had established decent relationships with George Washington

, commander of the army, as well as Philip Schuyler

and Horatio Gates

, both of whom had command of the army's Northern Department during 1775 and 1776. However, an acrimonious dispute with Moses Hazen

, commander of the 2nd Canadian Regiment

, boiled over into a court martial of Hazen at Ticonderoga during the summer of 1776. Only action by Gates, then his superior at Ticonderoga, prevented his own arrest on countercharges levelled by Hazen. He had also had disagreements with John Brown

and James Easton, two lower-level officers with political connections that resulted in ongoing suggestions of improprieties on his part. Brown was particularly vicious, publishing a handbill that claimed of Arnold, "Money is this man's God, and to get enough of it he would sacrifice his country".

General Washington assigned Arnold to the defense of Rhode Island

General Washington assigned Arnold to the defense of Rhode Island

following the British seizure of Newport

in December 1776, where the militia were too poorly equipped to even consider an attack on the British. Arnold took the opportunity while near his home in New Haven to visit his children, and he spent much of the winter socializing in Boston, where he unsuccessfully courted a young belle named Betsy Deblois. In February of 1777, he learned that he had been passed over for promotion to major general

by Congress. Washington refused his offer to resign, and wrote to members of Congress in an attempt to correct this, noting that "two or three other very good officers" might be lost if they persisted in making politically-motivated promotions. Arnold was on his way to Philadelphia to discuss his future when he was alerted that a British force was marching toward a supply depot in Danbury, Connecticut

. Along with David Wooster and Connecticut militia General Gold S. Silliman

he organized the militia response. In the Battle of Ridgefield

, he led a small contingent of militia attempting to stop or slow the British return to the coast, and was again wounded in his left leg. Arnold continued on to Philadelphia, where he met with members of Congress about his rank. His action at Ridgefield, coupled with the death of Wooster due to wounds sustained in the action, resulted in Arnold's promotion to major general, although his seniority was not restored over those who had been promoted before him. Amid negotiations over that issue, Arnold wrote out a letter of resignation on July 11, the same day word arrived in Philadelphia that Fort Ticonderoga had fallen to the British. Washington refused his resignation and ordered him north to assist with the defense there.

Arnold arrived in Schuyler's camp at Fort Edward, New York

on July 24. On August 13 Schuyler dispatched him with a force of 900 to relieve the siege of Fort Stanwix

, where he succeeded in the use of a ruse to lift the siege. Arnold had an Indian messenger sent into the camp of British Brigadier General Barry St. Leger

with news that the approaching force was much larger and closer than it actually was; this convinced St. Leger's Indian support to abandon him, forcing him to give up the effort.

Arnold then returned to the Hudson, where General Gates had taken over command of the American army, which had by then retreated to a camp south of Stillwater

. He then distinguished himself in both Battles of Saratoga, even though General Gates, following a series of escalating disagreements and disputes that culminated in a shouting match, removed him from field command after the first battle. During the fighting in the second battle, Arnold, operating against Gates' orders, took to the battlefield and led attacks on the British defenses. He was again severely wounded in the left leg late in the fighting. Arnold himself said it would have been better had it been in the chest instead of the leg. Burgoyne surrendered ten days after the second battle, on October 17, 1777. In response to Arnold's valor at Saratoga, Congress restored his command seniority. However, Arnold interpreted the manner in which they did so as an act of sympathy for his wounds, and not an apology or recognition that they were righting a wrong.

Arnold spent several months recovering from his injuries. Rather than amputating his shattered left leg, he had it crudely set, leaving it 2 inches (5 cm) shorter than the right. He returned to the army at Valley Forge

in May 1778 to the applause of men who had served under him at Saratoga. There he participated in the first recorded Oath of Allegiance

along with many other soldiers, as a sign of loyalty to the United States.

After the British withdrew from Philadelphia in June 1778 Washington appointed Arnold military commander of the city. Even before the Americans reoccupied Philadelphia, Arnold began planning to capitalize financially on the change in power there, engaging in a variety of business deals designed to profit from war-related supply movements and benefiting from the protection of his authority. These schemes were sometimes frustrated by powerful local politicians, who eventually amassed enough evidence to publicly air charges. Arnold demanded a court martial to clear the charges, writing to Washington in May 1779, "Having become a cripple in the service of my country, I little expected to meet [such] ungrateful returns".

Arnold lived extravagantly in Philadelphia, and was a prominent figure on the social scene. During the summer of 1778 Arnold met Peggy Shippen

, the 18-year-old daughter of Judge Edward Shippen

, a Loyalist sympathizer who had done business with the British while they occupied the city. Peggy had been courted by British Major John André

during the British occupation of Philadelphia. Peggy and Arnold married on April 8, 1779. Peggy and her circle of friends had found methods of staying in contact with paramours across the battle lines, despite military bans on communication with the enemy. Some of this communication was effected through the services of Joseph Stansbury, a Philadelphia merchant.

Sometime early in May 1779, Arnold met with Stansbury. Stansbury, whose testimony before a British commission apparently erroneously placed the date in June, said that, after meeting with Arnold, "I went secretly to New York with a tender of [Arnold's] services to Sir Henry Clinton

." Ignoring instructions from Arnold to involve no one else in the plot, Stansbury crossed the British lines and went to see Jonathan Odell

in New York. Odell was a Loyalist working with William Franklin

, the last colonial governor of New Jersey

and the son of Benjamin Franklin

. On May 9, Franklin introduced Stansbury to Major André, who had just been named the British spy chief. This was the beginning of a secret correspondence between Arnold and André, sometimes using his wife Peggy as a willing intermediary, that culminated over a year later with Arnold's change of sides.

André conferred with General Clinton, who gave him broad authority to pursue Arnold's offer. André then drafted instructions to Stansbury and Arnold. This initial letter opened a discussion on the types of assistance and intelligence Arnold might provide, and included instructions for how to communicate in the future. Letters would be passed through the women's circle that Peggy Arnold was a part of, but only Peggy would be aware that some letters contained instructions written in both code

André conferred with General Clinton, who gave him broad authority to pursue Arnold's offer. André then drafted instructions to Stansbury and Arnold. This initial letter opened a discussion on the types of assistance and intelligence Arnold might provide, and included instructions for how to communicate in the future. Letters would be passed through the women's circle that Peggy Arnold was a part of, but only Peggy would be aware that some letters contained instructions written in both code

and invisible ink

that were to be passed on to André, using Stansbury as the courier.

By July 1779, Arnold was providing the British with troop locations and strengths, as well as the locations of supply depots, all the while negotiating over compensation. At first, he asked for indemnification of his losses and £10,000, an amount the Continental Congress had given Charles Lee

for his services in the Continental Army. General Clinton, who was pursuing a campaign to gain control of the Hudson River Valley, was interested in plans and information on the defenses of West Point and other defenses on the Hudson River. He also began to insist on a face-to-face meeting, and suggested to Arnold that he pursue another high-level command. By October 1779, the negotiations had ground to a halt. Furthermore, Patriot mobs were scouring Philadelphia for Loyalists, and Arnold and the Shippen family were being threatened. Arnold was rebuffed by Congress and by local authorities in requests for security details for himself and his in-laws.

, throwing the army into a flurry of activity to react. Although a number of members of the panel of judges were ill-disposed to Arnold over actions and disputes earlier in the war, Arnold was cleared of all but two minor charges on January 26, 1780. Arnold worked over the next few months to publicize this fact; however, in early April, just one week after Washington congratulated Arnold on the March 19 birth of his son, Edward Shippen Arnold, Washington published a formal rebuke of Arnold's behavior.

Shortly after Washington's rebuke, a Congressional inquiry into his expenditures concluded that Arnold had failed to fully account for his expenditures incurred during the Quebec invasion, and that he owed the Congress some £1,000, largely because he was unable to document them. A significant number of these documents were lost during the retreat from Quebec; angry and frustrated, Arnold resigned his military command of Philadelphia in late April.

Shortly after Washington's rebuke, a Congressional inquiry into his expenditures concluded that Arnold had failed to fully account for his expenditures incurred during the Quebec invasion, and that he owed the Congress some £1,000, largely because he was unable to document them. A significant number of these documents were lost during the retreat from Quebec; angry and frustrated, Arnold resigned his military command of Philadelphia in late April.

. (Arnold did not know that this proposed invasion was a ruse intended to divert British resources.) On June 16, Arnold inspected West Point while on his way home to Connecticut to take care of personal business, and sent a highly detailed report through the secret channel. When he reached Connecticut Arnold arranged to sell his home there, and began transferring assets to London through intermediaries in New York. By early July he was back in Philadelphia, where he wrote another secret message to Clinton on July 7, which implied that his appointment to West Point was assured and that he might even provide a "drawing of the works ... by which you might take [West Point] without loss".

General Clinton and Major André, who returned victorious from the Siege of Charleston

on June 18, were immediately caught up in this news. Clinton, concerned that Washington's army and the French fleet would join in Rhode Island, again fixed on West Point as a strategic point to capture. André, who had spies and informers keeping track of Arnold, verified his movements. Excited by the prospects, Clinton informed his superiors of his intelligence coups, but failed to respond to Arnold's July 7 letter.

Arnold next wrote a series of letters to Clinton, even before he might have expected a response to the July 7 letter. In a July 11 letter, he complained that the British did not appear to trust him, and threatened to break off negotiations unless progress was made. On July 12 he wrote again, making explicit the offer to surrender West Point, although his price (in addition to indemnification for his losses) rose to £20,000, with a £1,000 downpayment to be delivered with the response. These letters were delivered not by Stansbury but by Samuel Wallis, another Philadelphia businessman who spied for the British.

Washington, in assigning Arnold to the command at West Point, also gave him authority over the entire American-controlled Hudson River, from Albany down to the British lines outside New York City. While en route to West Point, Arnold renewed an acquaintance with Joshua Hett Smith, someone Arnold knew had done spy work for both sides, and who owned a house near the western bank of the Hudson just south of West Point.

Once he established himself at West Point, Arnold began systematically weakening its defenses and military strength. Needed repairs on the chain across the Hudson

were never ordered. Troops were liberally distributed within Arnold's command area (but only minimally at West Point itself), or furnished to Washington on request. He also peppered Washington with complaints about the lack of supplies, writing, "Everything is wanting". At the same time, he tried to drain West Point's supplies, so that a siege would be more likely to succeed. His subordinates, some of whom were long-time associates, grumbled about unnecessary distribution of supplies, and eventually concluded that Arnold was selling some of the supplies on the black market for personal gain.

On August 30, Arnold sent a letter accepting Clinton's terms and proposing a meeting to André through yet another intermediary: William Heron, a member of the Connecticut Assembly he thought he could trust. Heron, in a comic twist, went into New York unaware of the significance of the letter, and offered his own services to the British as a spy. He then took the letter back to Connecticut, where, suspicious of Arnold's actions, he delivered it to the head of the Connecticut militia. General Parsons, seeing a letter written as a coded business discussion, laid it aside. Four days later, Arnold sent a ciphered letter with similar content into New York through the services of a prisoner-of-war's wife. Eventually, a meeting was set for September 11 near Dobb's Ferry. This meeting was thwarted when British gunboats in the river, not having been informed of his impending arrival, fired on his boat.

On August 30, Arnold sent a letter accepting Clinton's terms and proposing a meeting to André through yet another intermediary: William Heron, a member of the Connecticut Assembly he thought he could trust. Heron, in a comic twist, went into New York unaware of the significance of the letter, and offered his own services to the British as a spy. He then took the letter back to Connecticut, where, suspicious of Arnold's actions, he delivered it to the head of the Connecticut militia. General Parsons, seeing a letter written as a coded business discussion, laid it aside. Four days later, Arnold sent a ciphered letter with similar content into New York through the services of a prisoner-of-war's wife. Eventually, a meeting was set for September 11 near Dobb's Ferry. This meeting was thwarted when British gunboats in the river, not having been informed of his impending arrival, fired on his boat.

, the colonel in charge of the outpost at Verplanck's Point, fired on HMS Vulture, the ship that was intended to carry André back to New York. This action did sufficient damage that she was retreated downriver, forcing André to return to New York overland. Arnold wrote out passes for André so that he would be able to pass through the lines, and also gave him plans for West Point. On Saturday, September 23, André was captured, near Tarrytown

, by three Westchester patriots named John Paulding, Isaac Van Wart and David Williams; the papers exposing the plot to capture West Point were found and sent to Washington, and Arnold's treachery came to light after Washington examined them. Meanwhile, André convinced the unsuspecting commanding officer to whom he was delivered, Colonel John Jameson, to send him back to Arnold at West Point. However, Major Benjamin Tallmadge

, a member of Washington's secret service, insisted Jameson order the prisoner intercepted and brought back. Jameson reluctantly recalled the lieutenant delivering André into Arnold's custody, but then sent the same lieutenant as a messenger to notify Arnold of André's arrest.

Arnold learned of André's capture the following morning, September 24, when he received Jameson's message that André was in his custody and that the papers André was carrying had been sent to General Washington. Arnold received Jameson's letter while waiting for Washington, with whom he had planned to have breakfast. He made all haste to the shore and ordered bargemen to row him downriver to where the Vulture was anchored, which then took him to New York. From the ship Arnold wrote a letter to Washington, requesting that Peggy be given safe passage to her family in Philadelphia, a request Washington granted. When presented with evidence of Arnold's betrayal, it is reported that Washington was calm. He did, however, investigate the extent of the betrayal, and suggested in negotiations with General Clinton over the fate of Major André that he was willing to exchange André for Arnold. This suggestion Clinton refused; after a military tribunal, André was hanged at Tappan, New York

on October 2. Washington also infiltrated men into New York in an attempt to kidnap Arnold; this plan, which very nearly succeeded, failed when Arnold changed living quarters prior to sailing for Virginia in December.

Arnold attempted to justify his actions in an open letter titled To the Inhabitants of America, published in newspapers in October 1780. In the letter to Washington requesting safe passage for Peggy, he wrote that "Love to my country actuates my present conduct, however it may appear inconsistent to the world, who very seldom judge right of any man's actions."

, where he captured Richmond

by surprise and then went on a rampage through Virginia, destroying supply houses, foundries, and mills. This activity brought Virginia's militia out, and Arnold eventually retreated to Portsmouth

to either be evacuated or reinforced. The pursuing American army included the Marquis de Lafayette, who was under orders from Washington to summarily hang Arnold if he was captured. Reinforcements led by William Phillips (who served under Burgoyne at Saratoga) arrived in late March, and Phillips led further raids across Virginia, including a defeat of Baron von Steuben

at Petersburg

, until his death of fever on May 12, 1781. Arnold commanded the army only until May 20, when Lord Cornwallis

arrived with the southern army and took over. One colonel wrote to Clinton of Arnold, "there are many officers who must wish some other general in command". Cornwallis ignored advice proffered by Arnold to locate a permanent base away from the coast that might have averted his later surrender at Yorktown

.

On his return to New York in June, Arnold made a variety of proposals for continuing to attack essentially economic targets in order to force the Americans to end the war. Clinton, however, was not interested in most of Arnold's aggressive ideas, but finally relented and authorized Arnold to raid the port of New London, Connecticut

On his return to New York in June, Arnold made a variety of proposals for continuing to attack essentially economic targets in order to force the Americans to end the war. Clinton, however, was not interested in most of Arnold's aggressive ideas, but finally relented and authorized Arnold to raid the port of New London, Connecticut

. On September 4, not long after the birth of his and Peggy's second son, Arnold's force of over 1,700 men raided and burned New London

and captured Fort Griswold

, causing damage estimated at $500,000. British casualties were high—nearly one quarter of the force was killed or wounded, a rate at which Clinton claimed he could ill afford more such victories.

Even before Cornwallis' surrender in October, Arnold had requested permission from Clinton to go to England to give Lord Germain

his thoughts on the war in person. When word of the surrender reached New York, Arnold renewed the request, which Clinton then granted. On December 8, 1781, Arnold and his family left New York for England. In London he aligned himself with the Tories, advising Germain and King George III to renew the fight against the Americans. In the House of Commons, Edmund Burke

expressed the hope that the government would not put Arnold "at the head of a part of a British army" lest "the sentiments of true honor, which every British officer [holds] dearer than life, should be afflicted." To Arnold's detriment the anti-war Whigs

had gotten the upper hand in Parliament, and Germain was forced to resign, with the government of Lord North

falling not long after.

Arnold then applied to accompany General Carleton, who was going to New York to replace Clinton as commander-in-chief; this request went nowhere. Other attempts to gain positions within the government or the British East India Company

over the next few years all failed, and he was forced to subsist on the reduced pay of non-wartime service. His reputation also came under criticism in the British press, especially when compared to that of Major André, who was celebrated for his patriotism. One particularly harsh critic said that he was a "mean mercenary, who, having adopted a cause for the sake of plunder, quits it when convicted of that charge." In turning him down for an East India Company posting, George Johnstone wrote, "Although I am satisfied with the purity of your conduct, the generality do not think so. While this is the case, no power in this country could suddenly place you in the situation you aim at under the East India Company."

In 1785 Arnold and his son Richard moved to Saint John, New Brunswick

In 1785 Arnold and his son Richard moved to Saint John, New Brunswick

, where they speculated in land, and established a business doing trade with the West Indies. Arnold purchased large tracts of land in the Maugerville

area, and acquired city lots in Saint John and Fredericton

. Delivery of his first ship, the Lord Sheffield, was accompanied by accusations from the builder that Arnold had cheated him; Arnold claimed that he had merely deducted the contractually agreed amount when the ship was delivered late. After her first voyage, Arnold returned to London in 1786 to bring his family to Saint John. While there he disentangled himself from a lawsuit over an unpaid debt that Peggy had been fighting while he was away, paying £900 to settle a £12,000 loan he had taken while living in Philadelphia. The family moved to Saint John in 1787, where Arnold created an uproar with a series of bad business deals and petty lawsuits. Following the most serious, a slander suit he won against a former business partner, townspeople burned him in effigy in front of his house as Peggy and the children watched. The family left Saint John to return to London in December 1791.

In July 1792 he fought a bloodless duel

with the Earl of Lauderdale

after the Earl impugned his honor in the House of Lords

. With the outbreak of the French Revolution

Arnold outfitted a privateer

, while continuing to do business in the West Indies, even though the hostilities increased the risk. He was imprisoned by French authorities on Guadeloupe

amid accusations of spying for the British, and narrowly eluded hanging by escaping to the blockading British fleet

after bribing his guards. He helped organize militia forces on British-held islands, receiving praise from the landowners for his efforts on their behalf. This work, which he hoped would earn him wider respect and a new command, instead earned him and his sons a land grant of 15000 acres (6,070.3 ha) in Upper Canada

, near present-day Renfrew, Ontario

.

, from which he had suffered since 1775, attacked his unwounded leg to the point where he was unable to go to sea; the other ached constantly, and he walked only with a cane. His physicians diagnosed him as having dropsy

, and a visit to the countryside only temporarily improved his condition. He died after four days of delirium

, on June 14, 1801, at the age of 60. Legend has it that when he was on his deathbed he said, "Let me die in this old uniform in which I fought my battles. May God forgive me for ever having put on another," but this may be apocryphal. Arnold was buried at St. Mary's Church, Battersea

in London, England. As a result of a clerical error in the parish records, his remains were removed to an unmarked mass grave during church renovations a century later. His funeral procession boasted "seven mourning coaches and four state carriages"; the funeral was without military honors.

He left a small estate, reduced in size by his debts, which Peggy undertook to clear. Among his bequests were considerable gifts to one John Sage. Most historians (notably his American biographers Willard Sterne Randall and Clare Brandt) claim that Sage is an illegitimate son conceived during his time in New Brunswick. Canadian historian Barry Wilson, however, points out that this conventional account is contradicted by two basic facts. Although there are no birth records for Sage, his gravestone indicates that he was born on April 14, 1786. This date is roughly confirmed by Arnold's will, which stated Sage was 14 when he wrote it in 1800. Arnold arrived in New Brunswick in December 1785, meaning Sage's mother could not be from there. Wilson believes the explanation most consistent with the available documentation is that Sage was either the result of a liaison before Arnold left England, or that he was Arnold's grandson by one of his older children.

themes were often invoked; Benjamin Franklin

wrote that "Judas

sold only one man, Arnold three millions", and Alexander Scammel described Arnold's actions as "black as hell".

Early biographers attempted to describe Arnold's entire life in terms of treacherous or morally questionable behavior. The first major biography of Arnold, The Life and Treason of Benedict Arnold, published in 1832 by historian Jared Sparks

Early biographers attempted to describe Arnold's entire life in terms of treacherous or morally questionable behavior. The first major biography of Arnold, The Life and Treason of Benedict Arnold, published in 1832 by historian Jared Sparks

, was particularly harsh in showing how Arnold's treacherous character was allegedly formed out of childhood experiences. George Canning Hill, who authored a series of moralistic biographies in the mid-19th century, began his 1865 biography of Arnold "Benedict, the Traitor, was born ...". Social historian Brian Carso notes that as the 19th century progressed, the story of Arnold's betrayal took on near-mythic proportions as a part of the national creation story, and was again invoked as sectional conflicts leading up the American Civil War

increased. Washington Irving

used it as part of an argument against dismemberment of the union in his 1857 Life of George Washington, pointing out that only the unity of New England and the southern states that led to independence was made possible in part by holding West Point. Jefferson Davis

and other southern secessionist leaders were unfavorably compared to Arnold, implicitly and explicitly likening the idea of secession to treason. Harper's Weekly

published an article in 1861 describing Confederate

leaders as "a few men directing this colossal treason, by whose side Benedict Arnold shines white as a saint."

Fictional invocations of Arnold's name also carried strongly negative overtones. A moralistic children's tale entitled "The Cruel Boy" was widely circulated in the 19th century. It described a boy who stole eggs from birds' nests, pulled wings off insects, and engaged in other sorts of wanton cruelty, who then grew up to become a traitor to his country. The boy is not identified until the end of the story, when his place of birth is given as Norwich, Connecticut, and his name is given as Benedict Arnold. However, not all depictions of Arnold were strongly negative. Some theatrical treatments of the 19th century explored his duplicity, seeking to understand rather than demonize it.

The connection between Arnold and treason continued into the 20th and 21st centuries. On an episode of The Brady Bunch

, "Everyone Can't Be George Washington", after Peter is assigned the role of Arnold in the school play, everyone hates him. Dan Gilbert, owner of the National Basketball Association

's Cleveland Cavaliers

, subtly invoked Arnold in 2010. Upset over the manner in which LeBron James

announced his departure from the team, Gilbert's company lowered the price of posters bearing James's likeness to $17.41, referring to the year of Arnold's birth.

Novelistic treatments of the American Revolutionary war sometimes feature Arnold as a character. One notable treatment, depicting Arnold very much in a positive light, is Kenneth Roberts' Arundel

novels, which cover many of the campaigns in which he participated:

, but later in lands further west, where they established settlements in Saskatchewan

. His descendants, most of all those of John Sage, who apparently adopted the Arnold surname, are spread across Canada. His military jacket continues to be owned by the family, and was, as of 2001, held in Saskatchewan. It has supposedly been passed in each generation to the eldest male of the family.

During his marriage to Margaret Mansfield, Arnold had the following children:

During his marriage to Margaret Mansfield, Arnold had the following children:

and with Peggy Shippen

, he raised a family active in British military service:

, stands a monument in memorial to Arnold, but there is no mention of his name on the engraving. Donated by Civil War

General John Watts DePeyster, the inscription on the Boot Monument

reads: "In memory of the most brilliant soldier of the Continental army, who was desperately wounded on this spot, winning for his countrymen the decisive battle of the American Revolution, and for himself the rank of Major General." The victory monument at Saratoga has four niches, three of which are occupied by statues of Generals Gates, Schuyler, and Morgan. The fourth niche is empty.

On the grounds of the United States Military Academy

at West Point

there are plaques commemorating all of the generals that served in the Revolution. One plaque bears only a rank, "major general" and a date, "born 1740", and no name.

The house at 62 Gloucester Place where Arnold lived in central London still stands, bearing a plaque that describes Arnold as an "American Patriot". The church where Arnold was buried, St. Mary's Church, Battersea, England, has a commemorative stained-glass window which was added between 1976 and 1982. The faculty club at the University of New Brunswick

, Fredericton

, has a Benedict Arnold Room, in which framed original letters written by Arnold hang on the walls.

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War , the American War of Independence, or simply the Revolutionary War, began as a war between the Kingdom of Great Britain and thirteen British colonies in North America, and ended in a global war between several European great powers.The war was the result of the...

. He began the war in the Continental Army

Continental Army

The Continental Army was formed after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War by the colonies that became the United States of America. Established by a resolution of the Continental Congress on June 14, 1775, it was created to coordinate the military efforts of the Thirteen Colonies in...

but later defected

Defection

In politics, a defector is a person who gives up allegiance to one state or political entity in exchange for allegiance to another. More broadly, it involves abandoning a person, cause or doctrine to whom or to which one is bound by some tie, as of allegiance or duty.This term is also applied,...

to the British Army

British Army

The British Army is the land warfare branch of Her Majesty's Armed Forces in the United Kingdom. It came into being with the unification of the Kingdom of England and Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707. The new British Army incorporated Regiments that had already existed in England...

. While a general on the American side, he obtained command of the fort at West Point

West Point, New York

West Point is a federal military reservation established by President of the United States Thomas Jefferson in 1802. It is a census-designated place located in Town of Highlands in Orange County, New York, United States. The population was 7,138 at the 2000 census...

, New York

New York

New York is a state in the Northeastern region of the United States. It is the nation's third most populous state. New York is bordered by New Jersey and Pennsylvania to the south, and by Connecticut, Massachusetts and Vermont to the east...

, and plotted to surrender it to the British

Kingdom of Great Britain

The former Kingdom of Great Britain, sometimes described as the 'United Kingdom of Great Britain', That the Two Kingdoms of Scotland and England, shall upon the 1st May next ensuing the date hereof, and forever after, be United into One Kingdom by the Name of GREAT BRITAIN. was a sovereign...

forces. After the plot was exposed in September 1780, he was commissioned into the British Army as a brigadier general.

Born in Connecticut

Connecticut Colony

The Connecticut Colony or Colony of Connecticut was an English colony located in British America that became the U.S. state of Connecticut. Originally known as the River Colony, it was organized on March 3, 1636 as a haven for Puritan noblemen. After early struggles with the Dutch, the English...

, Arnold was a merchant operating ships on the Atlantic Ocean

Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's oceanic divisions. With a total area of about , it covers approximately 20% of the Earth's surface and about 26% of its water surface area...

when the war broke out in 1775. After joining the growing army outside Boston, he distinguished himself through acts of cunning and bravery. His actions included the Capture of Fort Ticonderoga

Capture of Fort Ticonderoga

The Capture of Fort Ticonderoga occurred during the American Revolutionary War on May 10, 1775, when a small force of Green Mountain Boys led by Ethan Allen and Colonel Benedict Arnold overcame a small British garrison at the fort and looted the personal belongings of the garrison...

in 1775, defensive and delaying tactics despite losing the Battle of Valcour Island

Battle of Valcour Island

The naval Battle of Valcour Island, also known as the Battle of Valcour Bay, took place on October 11, 1776, on Lake Champlain. The main action took place in Valcour Bay, a narrow strait between the New York mainland and Valcour Island...

on Lake Champlain

Lake Champlain

Lake Champlain is a natural, freshwater lake in North America, located mainly within the borders of the United States but partially situated across the Canada—United States border in the Canadian province of Quebec.The New York portion of the Champlain Valley includes the eastern portions of...

in 1776, the Battle of Ridgefield

Battle of Ridgefield

The Battle of Ridgefield was a battle and a series of skirmishes between American and British forces during the American Revolutionary War. The main battle was fought in the village of Ridgefield, Connecticut on April 27, 1777 and more skirmishing occurred the next day between Ridgefield and the...

, Connecticut (after which he was promoted to major general), operations in relief of the Siege of Fort Stanwix

Siege of Fort Stanwix

The Siege of Fort Stanwix began on August 2, 1777, and ended August 22. Fort Stanwix, in the Mohawk River Valley, was then the primary defense point for the Continental Army against British and Indian forces aligned against them in the American Revolutionary War...

, and key actions during the pivotal Battles of Saratoga in 1777, in which he suffered leg injuries that ended his combat career for several years.

Despite Arnold's successes, he was passed over for promotion by the Continental Congress

Continental Congress

The Continental Congress was a convention of delegates called together from the Thirteen Colonies that became the governing body of the United States during the American Revolution....

while other officers claimed credit for some of his accomplishments. Adversaries in military and political circles brought charges of corruption or other malfeasance, but most often he was acquitted in formal inquiries. Congress investigated his accounts and found he was indebted to Congress after spending much of his own money on the war effort. Frustrated and bitter, Arnold decided to change sides in 1779, and opened secret negotiations with the British. In July 1780, he sought and obtained command of West Point

West Point, New York

West Point is a federal military reservation established by President of the United States Thomas Jefferson in 1802. It is a census-designated place located in Town of Highlands in Orange County, New York, United States. The population was 7,138 at the 2000 census...

in order to surrender it to the British. Arnold's scheme was exposed when American forces captured British Major John André

John André

John André was a British army officer hanged as a spy during the American War of Independence. This was due to an incident in which he attempted to assist Benedict Arnold's attempted surrender of the fort at West Point, New York to the British.-Early life:André was born on May 2, 1750 in London to...

carrying papers that revealed the plot. Upon learning of André's capture, Arnold fled down the Hudson River

Hudson River

The Hudson is a river that flows from north to south through eastern New York. The highest official source is at Lake Tear of the Clouds, on the slopes of Mount Marcy in the Adirondack Mountains. The river itself officially begins in Henderson Lake in Newcomb, New York...

to the British sloop-of-war

Sloop-of-war

In the 18th and most of the 19th centuries, a sloop-of-war was a warship with a single gun deck that carried up to eighteen guns. As the rating system covered all vessels with 20 guns and above, this meant that the term sloop-of-war actually encompassed all the unrated combat vessels including the...

Vulture

HMS Vulture

Several vessels of the Royal Navy have been named HMS Vulture, including:, a Royalist ketch captured by the Parliamentary forces in 1648., a Dunkirk privateer captured in 1656, and sold in 1663., a sloop of 1673, sold 1686., a fireship of 1690, lost to the French in 1708., a 10/14-gun sloop of...

, narrowly avoiding capture by the forces of George Washington

George Washington

George Washington was the dominant military and political leader of the new United States of America from 1775 to 1799. He led the American victory over Great Britain in the American Revolutionary War as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army from 1775 to 1783, and presided over the writing of...

, who had been alerted to the plot.

Arnold received a commission as a brigadier general in the British Army

British Army

The British Army is the land warfare branch of Her Majesty's Armed Forces in the United Kingdom. It came into being with the unification of the Kingdom of England and Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707. The new British Army incorporated Regiments that had already existed in England...

, an annual pension of £360, and a lump sum of over £6,000. He led British forces on raids in Virginia

Virginia

The Commonwealth of Virginia , is a U.S. state on the Atlantic Coast of the Southern United States. Virginia is nicknamed the "Old Dominion" and sometimes the "Mother of Presidents" after the eight U.S. presidents born there...

, and against New London and Groton, Connecticut

Battle of Groton Heights

The Battle of Groton Heights was a battle of the American Revolutionary War fought on September 6, 1781 between a small Connecticut militia force led by Lieutenant Colonel William Ledyard and the more numerous British forces led by Brigadier General Benedict Arnold and Lieutenant...

, before the war effectively ended with the American victory at Yorktown

Siege of Yorktown

The Siege of Yorktown, Battle of Yorktown, or Surrender of Yorktown in 1781 was a decisive victory by a combined assault of American forces led by General George Washington and French forces led by the Comte de Rochambeau over a British Army commanded by Lieutenant General Lord Cornwallis...

. In the winter of 1782, Arnold moved to London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

with his second wife, Margaret "Peggy" Shippen Arnold

Peggy Shippen

Peggy Shippen, or Margaret Shippen , was the second wife of General Benedict Arnold...

. He was well received by King George III

George III of the United Kingdom

George III was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of these two countries on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland until his death...

and the Tories

Tories (political faction)

The Tories were members of two political parties which existed, sequentially, in the Kingdom of England, the Kingdom of Great Britain and later the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from the 17th to the early 19th centuries.-Overview:...

but frowned upon by the Whigs. In 1787, he entered into mercantile business with his sons Richard and Henry in Saint John, New Brunswick

Saint John, New Brunswick

City of Saint John , or commonly Saint John, is the largest city in the province of New Brunswick, and the first incorporated city in Canada. The city is situated along the north shore of the Bay of Fundy at the mouth of the Saint John River. In 2006 the city proper had a population of 74,043...

, but returned to London to settle permanently in 1791, where he died ten years later.

Because of the way he changed sides, his name quickly became a byword in the United States for treason

Treason

In law, treason is the crime that covers some of the more extreme acts against one's sovereign or nation. Historically, treason also covered the murder of specific social superiors, such as the murder of a husband by his wife. Treason against the king was known as high treason and treason against a...

or betrayal. His conflicting legacy is recalled in the ambiguous nature of some of the memorials that have been placed in his honor.

Early life

Benedict was born the second of six children to Benedict Arnold III (1683–1761) and Hannah Waterman King in NorwichNorwich, Connecticut

Regular steamship service between New York and Boston helped Norwich to prosper as a shipping center through the early part of the 20th century. During the Civil War, Norwich once again rallied and saw the growth of its textile, armaments, and specialty item manufacturing...

, Connecticut

Connecticut Colony

The Connecticut Colony or Colony of Connecticut was an English colony located in British America that became the U.S. state of Connecticut. Originally known as the River Colony, it was organized on March 3, 1636 as a haven for Puritan noblemen. After early struggles with the Dutch, the English...

, on January 14, 1741. He was named after his great-grandfather Benedict Arnold

Benedict Arnold (governor)

Benedict Arnold was president and then governor of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, serving for a total of 11 years in these roles. Coming from Somerset, England, he was born and raised in the town of Ilchester, likely attending school in Limington, nearby...

, an early governor of the Colony of Rhode Island, and his brother Benedict IV, who died in infancy. Only Benedict and his sister Hannah survived to adulthood; his other siblings succumbed to yellow fever

Yellow fever

Yellow fever is an acute viral hemorrhagic disease. The virus is a 40 to 50 nm enveloped RNA virus with positive sense of the Flaviviridae family....

in childhood. Through his maternal grandmother, Arnold was a descendant of John Lothropp, an ancestor of at least four U.S. presidents

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

.

Arnold's father was a successful businessman, and the family moved in the upper levels of Norwich society. When he was ten, Arnold was enrolled in a private school in nearby Canterbury

Canterbury, Connecticut

Canterbury is a town in Windham County, Connecticut, United States. The population was 4,692 at the 2000 census.-History:The area was first settled in the 1680s as Peagscomsuck, consisting mainly of land north of Norwich, south of New Roxbury, Massachusetts and west of the Quinebaug River and the...

, with the expectation that he would eventually attend Yale

Yale University

Yale University is a private, Ivy League university located in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701 in the Colony of Connecticut, the university is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States...

. However, the deaths of his siblings two years later may have contributed to a decline in the family fortunes, since his father took up drinking. By the time he was fourteen, there was no money for private education. His father's alcoholism

Alcoholism

Alcoholism is a broad term for problems with alcohol, and is generally used to mean compulsive and uncontrolled consumption of alcoholic beverages, usually to the detriment of the drinker's health, personal relationships, and social standing...

and ill health kept him from training Arnold in the family mercantile business, but his mother's family connections secured an apprenticeship for Arnold with two of her cousins, brothers Daniel and Joshua Lathrop, who operated a successful apothecary

Apothecary

Apothecary is a historical name for a medical professional who formulates and dispenses materia medica to physicians, surgeons and patients — a role now served by a pharmacist and some caregivers....

and general merchandise trade in Norwich. His apprenticeship with the Lathrops lasted seven years.

In 1755, Arnold, attracted by the sound of a drummer, attempted to enlist in the provincial militia

Militia

The term militia is commonly used today to refer to a military force composed of ordinary citizens to provide defense, emergency law enforcement, or paramilitary service, in times of emergency without being paid a regular salary or committed to a fixed term of service. It is a polyseme with...

for service against the French

French and Indian War

The French and Indian War is the common American name for the war between Great Britain and France in North America from 1754 to 1763. In 1756, the war erupted into the world-wide conflict known as the Seven Years' War and thus came to be regarded as the North American theater of that war...

, but his mother refused permission. In 1757, when he was sixteen, he did enlist in the militia, which marched off toward Albany

Albany, New York

Albany is the capital city of the U.S. state of New York, the seat of Albany County, and the central city of New York's Capital District. Roughly north of New York City, Albany sits on the west bank of the Hudson River, about south of its confluence with the Mohawk River...

and Lake George

Lake George (New York)

Lake George, nicknamed the Queen of American Lakes, is a long, narrow oligotrophic lake draining northwards into Lake Champlain and the St. Lawrence River Drainage basin located at the southeast base of the Adirondack Mountains in northern New York, U.S.A.. It lies within the upper region of the...

. The French had besieged Fort William Henry, and their Indian allies had committed atrocities after their victory. Word of the siege's disastrous outcome led the company to turn around; Arnold served for 13 days. A commonly accepted story that Arnold deserted from militia service in 1758 is based on uncertain documentary evidence.

Arnold's mother, to whom he was very close, died in 1759. His father's alcoholism worsened after the death of his wife, and the youth took on the responsibility of supporting his father and younger sister. His father was arrested on several occasions for public drunkenness, was refused communion

Eucharist

The Eucharist , also called Holy Communion, the Sacrament of the Altar, the Blessed Sacrament, the Lord's Supper, and other names, is a Christian sacrament or ordinance...

by his church, and eventually died in 1761.

Businessman

In 1762, with the help of the Lathrops, Arnold established himself in business as a pharmacistPharmacist

Pharmacists are allied health professionals who practice in pharmacy, the field of health sciences focusing on safe and effective medication use...

and bookseller in New Haven, Connecticut

New Haven, Connecticut

New Haven is the second-largest city in Connecticut and the sixth-largest in New England. According to the 2010 Census, New Haven's population increased by 5.0% between 2000 and 2010, a rate higher than that of the State of Connecticut, and higher than that of the state's five largest cities, and...

. Arnold was hardworking and successful, and was able to rapidly expand his business. In 1763 he repaid money borrowed from the Lathrops, repurchased the family homestead that his father had sold when deeply in debt, and re-sold it a year later for a substantial profit. In 1764 he formed a partnership with Adam Babcock, another young New Haven merchant. Using the profits from the sale of his homestead they bought three trading ships and established a lucrative West Indies trade. During this time he brought his sister Hannah to New Haven and established her in his apothecary to manage the business in his absence. He traveled extensively in the course of his business, throughout New England

New England

New England is a region in the northeastern corner of the United States consisting of the six states of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut...

and from Quebec

Province of Quebec (1763-1791)

The Province of Quebec was a colony in North America created by Great Britain after the Seven Years' War. Great Britain acquired Canada by the Treaty of Paris when King Louis XV of France and his advisors chose to keep the territory of Guadeloupe for its valuable sugar crops instead of New France...

to the West Indies, often in command of one of his own ships. On one of his voyages, Arnold fought a duel in Honduras

Honduras

Honduras is a republic in Central America. It was previously known as Spanish Honduras to differentiate it from British Honduras, which became the modern-day state of Belize...

with a British sea captain who had called him a "damned Yankee, destitute of good manners or those of a gentleman". The captain was wounded after the first exchange of gunfire, and apologized after Arnold threatened to aim to kill on the second.

The Sugar Act

Sugar Act

The Sugar Act, also known as the American Revenue Act or the American Duties Act, was a revenue-raising act passed by the Parliament of Great Britain on April 5, 1764. The preamble to the act stated: "it is expedient that new provisions and regulations should be established for improving the...

of 1764 and the Stamp Act

Stamp Act 1765

The Stamp Act 1765 was a direct tax imposed by the British Parliament specifically on the colonies of British America. The act required that many printed materials in the colonies be produced on stamped paper produced in London, carrying an embossed revenue stamp...

of 1765 severely curtailed mercantile trade

Mercantilism

Mercantilism is the economic doctrine in which government control of foreign trade is of paramount importance for ensuring the prosperity and security of the state. In particular, it demands a positive balance of trade. Mercantilism dominated Western European economic policy and discourse from...

in the colonies. The latter act prompted Arnold to join the chorus of voices in opposition to those taxes, and also led to his entry into the Sons of Liberty

Sons of Liberty

The Sons of Liberty were a political group made up of American patriots that originated in the pre-independence North American British colonies. The group was formed to protect the rights of the colonists from the usurpations by the British government after 1766...

, a secret organization that was not afraid to use violence to oppose implementation of those and other unpopular Parliamentary measures. Arnold initially took no part in any public demonstrations but, like many merchants, continued to trade as if the Stamp Act did not exist, in effect becoming a smuggler in defiance of the act. Arnold also faced financial ruin, falling £16,000 in debt, with creditors spreading rumors of his insolvency to the point where he took legal action against them. On the night of January 28, 1767, Arnold and members of his crew, watched by a crowd of Sons, roughed up a man suspected of attempting to inform authorities of Arnold's smuggling. Arnold was convicted of a disorderly conduct charge and fined the relatively small amount of 50 shillings; publicity of the case and widespread sympathy for his view probably contributed to the light sentence.

On February 22, 1767, he married Margaret Mansfield, daughter of Samuel Mansfield, the sheriff of New Haven, an acquaintance that may have been made through the membership of both Mansfield and Arnold in the local Masonic Lodge

Freemasonry

Freemasonry is a fraternal organisation that arose from obscure origins in the late 16th to early 17th century. Freemasonry now exists in various forms all over the world, with a membership estimated at around six million, including approximately 150,000 under the jurisdictions of the Grand Lodge...

. Their first son, Benedict VI, was born the following year, and was followed by brothers Richard in 1769, and Henry in 1772. Margaret died early in the revolution, on June 19, 1775, while Arnold was at Fort Ticonderoga

Fort Ticonderoga

Fort Ticonderoga, formerly Fort Carillon, is a large 18th-century fort built by the Canadians and the French at a narrows near the south end of Lake Champlain in upstate New York in the United States...

following its capture. The household, even while she lived, was dominated by Arnold's sister Hannah. Arnold benefited from his relationship with Mansfield, who became a partner in his business and used his position as sheriff to shield Arnold from creditors.

Arnold was in the West Indies when the Boston Massacre

Boston Massacre

The Boston Massacre, called the Boston Riot by the British, was an incident on March 5, 1770, in which British Army soldiers killed five civilian men. British troops had been stationed in Boston, capital of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, since 1768 in order to protect and support...

took place on March 5, 1770. He wrote he was "very much shocked" and wondered "good God, are the Americans all asleep and tamely giving up their liberties, or are they all turned philosophers, that they don't take immediate vengeance on such miscreants".

Early Revolutionary War

Arnold began the war as a captain in ConnecticutConnecticut Colony

The Connecticut Colony or Colony of Connecticut was an English colony located in British America that became the U.S. state of Connecticut. Originally known as the River Colony, it was organized on March 3, 1636 as a haven for Puritan noblemen. After early struggles with the Dutch, the English...

's militia, a position to which he was elected in March 1775. Following the outbreak of hostilities at Lexington and Concord

Battles of Lexington and Concord

The Battles of Lexington and Concord were the first military engagements of the American Revolutionary War. They were fought on April 19, 1775, in Middlesex County, Province of Massachusetts Bay, within the towns of Lexington, Concord, Lincoln, Menotomy , and Cambridge, near Boston...

the following month, his company marched northeast to assist in the siege of Boston

Siege of Boston

The Siege of Boston was the opening phase of the American Revolutionary War, in which New England militiamen—who later became part of the Continental Army—surrounded the town of Boston, Massachusetts, to prevent movement by the British Army garrisoned within...

that followed. Arnold proposed to the Massachusetts Committee of Safety

Committee of Safety (American Revolution)

Many Committees of Safety were established throughout Colonial America at the start of the American Revolution. These committees started to appear in the 1760s as means to discuss the concerns of the time, and often consisted of every male adult in the community...

an action to seize Fort Ticonderoga

Fort Ticonderoga

Fort Ticonderoga, formerly Fort Carillon, is a large 18th-century fort built by the Canadians and the French at a narrows near the south end of Lake Champlain in upstate New York in the United States...

in New York

New York

New York is a state in the Northeastern region of the United States. It is the nation's third most populous state. New York is bordered by New Jersey and Pennsylvania to the south, and by Connecticut, Massachusetts and Vermont to the east...

, which he knew was poorly defended. They issued him a colonel's commission on May 3, 1775, and he immediately rode off to the west, arriving at Castleton

Castleton, Vermont

Castleton is a town in Rutland County, Vermont, United States. Castleton is about to the west of Rutland, and about east of the New York/Vermont state border. The town had a population of 4,717 at the 2010 census. Castleton State College is located there, with roots dating to 1787...

in the disputed New Hampshire Grants

New Hampshire Grants

The New Hampshire Grants or Benning Wentworth Grants were land grants made between 1749 and 1764 by the provincial governor of New Hampshire, Benning Wentworth. The land grants, totaling about 135 , were made on land claimed by New Hampshire west of the Connecticut River, territory that was also...

(present-day Vermont

Vermont

Vermont is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States of America. The state ranks 43rd in land area, , and 45th in total area. Its population according to the 2010 census, 630,337, is the second smallest in the country, larger only than Wyoming. It is the only New England...

) in time to participate with Ethan Allen

Ethan Allen

Ethan Allen was a farmer, businessman, land speculator, philosopher, writer, and American Revolutionary War patriot, hero, and politician. He is best known as one of the founders of the U.S...

and his men in the capture of Fort Ticonderoga

Capture of Fort Ticonderoga

The Capture of Fort Ticonderoga occurred during the American Revolutionary War on May 10, 1775, when a small force of Green Mountain Boys led by Ethan Allen and Colonel Benedict Arnold overcame a small British garrison at the fort and looted the personal belongings of the garrison...

. He followed up that action with a bold raid on Fort Saint-Jean

Fort Saint-Jean (Quebec)

Fort Saint-Jean is a fort in the Canadian La Vallée-du-Richelieu Regional County Municipality, Quebec located on the Richelieu River. The fort was first built in 1666 by soldiers of the Carignan-Salières Regiment and was part of a series of forts built along the Richelieu River...

on the Richelieu River

Richelieu River

The Richelieu River is a river in Quebec, Canada. It flows from the north end of Lake Champlain about north, ending at the confluence with the St. Lawrence River at Sorel-Tracy, Quebec downstream and northeast of Montreal...

north of Lake Champlain

Lake Champlain

Lake Champlain is a natural, freshwater lake in North America, located mainly within the borders of the United States but partially situated across the Canada—United States border in the Canadian province of Quebec.The New York portion of the Champlain Valley includes the eastern portions of...

. When a Connecticut militia force arrived at Ticonderoga in June, he had a dispute with its commander over control of the fort, and resigned his Massachusetts commission. He was on his way home from Ticonderoga when he learned that his wife died earlier in June.

Second Continental Congress

The Second Continental Congress was a convention of delegates from the Thirteen Colonies that started meeting on May 10, 1775, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, soon after warfare in the American Revolutionary War had begun. It succeeded the First Continental Congress, which met briefly during 1774,...

authorized an invasion of Quebec

Invasion of Canada (1775)

The Invasion of Canada in 1775 was the first major military initiative by the newly formed Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. The objective of the campaign was to gain military control of the British Province of Quebec, and convince the French-speaking Canadiens to join the...

, in part on the urging of Arnold, he was passed over for command of the expedition. Arnold then went to Cambridge, Massachusetts

Cambridge, Massachusetts

Cambridge is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States, in the Greater Boston area. It was named in honor of the University of Cambridge in England, an important center of the Puritan theology embraced by the town's founders. Cambridge is home to two of the world's most prominent...

, and suggested to George Washington

George Washington

George Washington was the dominant military and political leader of the new United States of America from 1775 to 1799. He led the American victory over Great Britain in the American Revolutionary War as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army from 1775 to 1783, and presided over the writing of...

a second expedition to attack Quebec City

Quebec City

Quebec , also Québec, Quebec City or Québec City is the capital of the Canadian province of Quebec and is located within the Capitale-Nationale region. It is the second most populous city in Quebec after Montreal, which is about to the southwest...

via a wilderness route through present-day Maine

Maine

Maine is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States, bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the east and south, New Hampshire to the west, and the Canadian provinces of Quebec to the northwest and New Brunswick to the northeast. Maine is both the northernmost and easternmost...

. This expedition, for which Arnold received a colonel's commission in the Continental Army

Continental Army

The Continental Army was formed after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War by the colonies that became the United States of America. Established by a resolution of the Continental Congress on June 14, 1775, it was created to coordinate the military efforts of the Thirteen Colonies in...

, left Cambridge in September 1775 with 1,100 men. After a difficult passage in which 300 men turned back and another 200 died en route, Arnold arrived before Quebec City in November. Joined by Richard Montgomery

Richard Montgomery

Richard Montgomery was an Irish-born soldier who first served in the British Army. He later became a brigadier-general in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War and he is most famous for leading the failed 1775 invasion of Canada.Montgomery was born and raised in Ireland...

's small army, he participated in the December 31 assault on Quebec City

Battle of Quebec (1775)

The Battle of Quebec was fought on December 31, 1775 between American Continental Army forces and the British defenders of the city of Quebec, early in the American Revolutionary War. The battle was the first major defeat of the war for the Americans, and it came at a high price...

in which Montgomery was killed and Arnold's leg was shattered. Rev. Samuel Spring

Samuel Spring

Samuel Spring was an early American Revolutionary War chaplain and Congregationalist minister.-Early life and education:Spring was born in Uxbridge in the Massachusetts Colony on February 27, 1746....

, his chaplain, carried him to the makeshift hospital at the Hotel Dieu. Arnold, who was promoted to brigadier general for his role in reaching Quebec, maintained an ineffectual siege of the city until he was replaced by Major General David Wooster

David Wooster

David Wooster was an American general who served in the French and Indian War and in the American Revolutionary War. He died of wounds sustained during the Battle of Ridgefield, Connecticut. Cities, schools, and public places were named after him...

in April 1776.

Arnold then traveled to Montreal

Montreal

Montreal is a city in Canada. It is the largest city in the province of Quebec, the second-largest city in Canada and the seventh largest in North America...

, where he served as military commander of the city until forced to retreat by an advancing British army that had arrived at Quebec in May. He presided over the rear of the Continental Army during its retreat from Saint-Jean, where he was reported by James Wilkinson

James Wilkinson

James Wilkinson was an American soldier and statesman, who was associated with several scandals and controversies. He served in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, but was twice compelled to resign...