Bernard Spilsbury

Encyclopedia

Sir Bernard Henry Spilsbury (16 May 1877 – 17 December 1947) was an English pathologist. His cases include Hawley Harvey Crippen

, the Seddon

case and Major Armstrong

poisonings, the "brides in the bath" murders by George Joseph Smith

, Louis Voisin, Jean-Pierre Vaquier

, the Crumbles murders

, Norman Thorne

, Donald Merrett, the Podmore case

, the Sidney Harry Fox matricide

, the blazing Car murder, Mrs Barney, Tony Mancini

and the Vera Page case. He also had a critical role in developing Operation Mincemeat

, a deception operation during World War II which saved thousands of lives of Allied service personnel.

, Warwickshire

. He was the eldest of the four children of James Spilsbury, a manufacturing chemist, and his wife, Marion Elizabeth Joy.

On 3 September 1908, Spilsbury married Edith Caroline Horton. They had four children together: one daughter, Evelyn, and three sons, Alan, Peter, and Richard. Peter, a junior doctor, was killed in the Blitz and Alan died of TB shortly after the Second World War.

The deaths (of Peter, in particular) were a blow from which Spilsbury never truly recovered. Depression over his declining health is believed to have been a key factor in his decision to commit suicide by gas in December 1947, in his laboratory at University College London

.

In later years, his dogmatic manner and his unbending belief in his own infallibility gave rise to criticism; even in the later years of his life, judges began to express concern about his invincibility in court and recent researches have indicated that his inflexible dogmatism led to miscarriages of justice.

, Oxford

, he took a BA in natural science in 1899, M.B., B.Ch. in 1905 and an MA in 1908. He also studied at St Mary's Hospital

in London

from 1899. He specialised in the then-new science of forensic pathology. In October 1905 he was appointed resident assistant pathologist at St Mary's Hospital when the London County Council requested all general hospitals in its area to appoint two qualified pathologists to perform post-mortems related to sudden deaths.

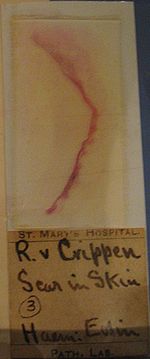

The case that brought Spilsbury to public attention was that of Dr Crippen in 1910, where he also gave forensic evidence in the trial about the likely identity of the human remains found in Crippen's house. Spilsbury concluded that a scar on a small piece of skin from the remains pointed to Mrs Crippen as the victim.

The case that brought Spilsbury to public attention was that of Dr Crippen in 1910, where he also gave forensic evidence in the trial about the likely identity of the human remains found in Crippen's house. Spilsbury concluded that a scar on a small piece of skin from the remains pointed to Mrs Crippen as the victim.

He gave evidence at the trial of Herbert Rowse Armstrong

, the solicitor convicted of poisoning his wife with arsenic

.

But the case that put him on the road to becoming Britain's most famous forensic pathologists was the Brides in the Bath murder trial of 1915. Three women had died mysteriously in their baths, in each case the death seeming to be an accident. George Joseph Smith

was brought to trial for the murder on one of these women - Bessie Mundy. Spilsbury testified that since Bessie's thigh showed evidence of 'goose skin', and since she was, in death, clutching a bar of soap - it was certain that she had died a violent death, and in fact has been murdered. It elevated Spilsbury to be seen as a 'medical detective', and he became known as a real-life Sherlock Holmes

.

He was also involved in the case of the Brighton trunk murders

, and although the accused man, Mancini, in whose flat the body of a murdered prostitute was found, was acquitted at the trial, Mancini confessed to the killing just before his own death, many years later, so vindicating Spilsbury's evidence.

He was able to work with minimal remains, such as that involved in the "Blazing car murder", when a near destroyed body was found in the wreck of a burnt-out car near Northampton

in 1930. He gave evidence of how the man had died, although the victim was never identified, and so helped convict Alfred Rouse

. During his career Spilsbury performed thousands of autopsies

, not only for murder victims but also of executed criminals. He was able to appear for the defence in Scotland, where his status as a Home Office pathologist in England and Wales was irrelevant: he testified for the defence in the case of Donald Merrett, tried in February 1927 for the murder of his mother and acquitted as not proven

.

Spilsbury was knighted

in 1923. He was a Home Office

approved pathologist, lecturer in forensic medicine in the University College Hospital

, London School of Medicine for Women

and St. Thomas' Hospital. He also was a Fellow of the Royal Society of Medicine

.

Files containing notes on deaths investigated by Spilsbury went under the hammer at Sotheby's on 17 July 2008, when they were acquired by the Wellcome Library

in London. The index card

s documented deaths in London and the Home Counties from 1905 to 1932. The hand-written cards, discovered in a lost cabinet, were the notes that Spilsbury apparently accumulated for a textbook on forensic medicine which he was planning, but there is no evidence that he ever started the book.

Radio 4's afternoon play The Incomparable Witness by Nichola McAuliffe

was a drama about Sir Bernard Spilsbury, 'the father of modern forensics'.

Spilsbury was commemorated by an English Heritage

Blue plaque

attached to his former home at Marlborough Hill, London, NW8

noted how "the virtuosity" of Spilsbury's performances in the mortuary and the courtroom "threatened to undermine the foundations of forensic pathology as a modern and objective specialism". Spilsbury is particularly criticised for his insistence on working alone; a refusal to train students; and an unwillingness to engage in academic research or peer review. This, says the article's author, "lent him an aura of infallibility that for many raised concerns that it was his celebrity rather than his science that persuaded juries to credit his evidence over all others."

Hawley Harvey Crippen

Hawley Harvey Crippen , usually known as Dr. Crippen, was an American homeopathic physician hanged in Pentonville Prison, London, on November 23, 1910, for the murder of his wife, Cora Henrietta Crippen...

, the Seddon

Frederick Seddon

Frederick Henry Seddon was a British poisoner who was hanged in 1912 for murdering Eliza Mary Barrow.-Background:...

case and Major Armstrong

Herbert Rowse Armstrong

Herbert Rowse Armstrong TD. MA. was an English solicitor and convicted murderer, the only solicitor in the history of the United Kingdom to have been hanged for murder...

poisonings, the "brides in the bath" murders by George Joseph Smith

George Joseph Smith

George Joseph Smith was an English serial killer and bigamist. In 1915 he was convicted and subsequently hanged for the slayings of three women, the case becoming known as the "Brides in the Bath Murders". As well as being widely reported in the media, the case was a significant case in the...

, Louis Voisin, Jean-Pierre Vaquier

Jean-Pierre Vaquier

Jean-Pierre Vaquier was a French inventor and murderer.He was tried for the murder of Alfred George Poynter Jones, landlord of the Blue Anchor pub in Byfleet, the husband of his mistress Mabel Jones, by poisoning him with strychnine.Vaquier had met Mabel Jones early in 1924 in Biarritz where she...

, the Crumbles murders

Crumbles murders

The Crumbles Murders may refer to one of two crimes that took place on "The Crumbles", a shingle beach between Eastbourne and Pevensey Bay — the 1920 murder of Irene Munro by Field and Gray, and the 1924 double murder of Emily Kaye and her unborn infant by Patrick Mahon.-Irene Munro:Irene...

, Norman Thorne

Norman Thorne

Norman Thorne was an English chicken farmer and murderer. He murdered his mistress Elsie Cameron on 5 December 1924 and dismembered the body....

, Donald Merrett, the Podmore case

Podmore case

The Podmore case was a controversial landmark British criminal case. It involved a murder conviction based on a painstaking police investigation, and from careful evaluation of the forensic evidence.- The crime :...

, the Sidney Harry Fox matricide

Matricide

Matricide is the act of killing one's mother. As for any type of killing, motives can vary significantly.- Known or suspected matricides :* Amastris, queen of Heraclea, was drowned by her two sons in 284 BC....

, the blazing Car murder, Mrs Barney, Tony Mancini

Brighton trunk murders

The Brighton trunk murders were two unrelated murders linked to Brighton, England in 1934. In both, the dismembered body of a murdered woman was placed in a trunk....

and the Vera Page case. He also had a critical role in developing Operation Mincemeat

Operation Mincemeat

Operation Mincemeat was a successful British deception plan during World War II. As part of the widespread deception plan Operation Barclay to cover the intended invasion of Italy from North Africa, Mincemeat helped to convince the German high command that the Allies planned to invade Greece and...

, a deception operation during World War II which saved thousands of lives of Allied service personnel.

Personal life

Spilsbury was born on 16 May 1877 at 35 Bath Street, Leamington SpaLeamington Spa

Royal Leamington Spa, commonly known as Leamington Spa or Leamington or Leam to locals, is a spa town in central Warwickshire, England. Formerly known as Leamington Priors, its expansion began following the popularisation of the medicinal qualities of its water by Dr Kerr in 1784, and by Dr Lambe...

, Warwickshire

Warwickshire

Warwickshire is a landlocked non-metropolitan county in the West Midlands region of England. The county town is Warwick, although the largest town is Nuneaton. The county is famous for being the birthplace of William Shakespeare...

. He was the eldest of the four children of James Spilsbury, a manufacturing chemist, and his wife, Marion Elizabeth Joy.

On 3 September 1908, Spilsbury married Edith Caroline Horton. They had four children together: one daughter, Evelyn, and three sons, Alan, Peter, and Richard. Peter, a junior doctor, was killed in the Blitz and Alan died of TB shortly after the Second World War.

The deaths (of Peter, in particular) were a blow from which Spilsbury never truly recovered. Depression over his declining health is believed to have been a key factor in his decision to commit suicide by gas in December 1947, in his laboratory at University College London

University College London

University College London is a public research university located in London, United Kingdom and the oldest and largest constituent college of the federal University of London...

.

In later years, his dogmatic manner and his unbending belief in his own infallibility gave rise to criticism; even in the later years of his life, judges began to express concern about his invincibility in court and recent researches have indicated that his inflexible dogmatism led to miscarriages of justice.

Career

Educated at Magdalen CollegeMagdalen College, Oxford

Magdalen College is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England. As of 2006 the college had an estimated financial endowment of £153 million. Magdalen is currently top of the Norrington Table after over half of its 2010 finalists received first-class degrees, a record...

, Oxford

Oxford

The city of Oxford is the county town of Oxfordshire, England. The city, made prominent by its medieval university, has a population of just under 165,000, with 153,900 living within the district boundary. It lies about 50 miles north-west of London. The rivers Cherwell and Thames run through...

, he took a BA in natural science in 1899, M.B., B.Ch. in 1905 and an MA in 1908. He also studied at St Mary's Hospital

St Mary's Hospital (London)

St Mary's Hospital is a hospital located in Paddington, London, England that was founded in 1845. Since the UK's first academic health science centre was created in 2008, it is operated by Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, which also operates Charing Cross Hospital, Hammersmith Hospital,...

in London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

from 1899. He specialised in the then-new science of forensic pathology. In October 1905 he was appointed resident assistant pathologist at St Mary's Hospital when the London County Council requested all general hospitals in its area to appoint two qualified pathologists to perform post-mortems related to sudden deaths.

Important cases

He gave evidence at the trial of Herbert Rowse Armstrong

Herbert Rowse Armstrong

Herbert Rowse Armstrong TD. MA. was an English solicitor and convicted murderer, the only solicitor in the history of the United Kingdom to have been hanged for murder...

, the solicitor convicted of poisoning his wife with arsenic

Arsenic

Arsenic is a chemical element with the symbol As, atomic number 33 and relative atomic mass 74.92. Arsenic occurs in many minerals, usually in conjunction with sulfur and metals, and also as a pure elemental crystal. It was first documented by Albertus Magnus in 1250.Arsenic is a metalloid...

.

But the case that put him on the road to becoming Britain's most famous forensic pathologists was the Brides in the Bath murder trial of 1915. Three women had died mysteriously in their baths, in each case the death seeming to be an accident. George Joseph Smith

George Joseph Smith

George Joseph Smith was an English serial killer and bigamist. In 1915 he was convicted and subsequently hanged for the slayings of three women, the case becoming known as the "Brides in the Bath Murders". As well as being widely reported in the media, the case was a significant case in the...

was brought to trial for the murder on one of these women - Bessie Mundy. Spilsbury testified that since Bessie's thigh showed evidence of 'goose skin', and since she was, in death, clutching a bar of soap - it was certain that she had died a violent death, and in fact has been murdered. It elevated Spilsbury to be seen as a 'medical detective', and he became known as a real-life Sherlock Holmes

Sherlock Holmes

Sherlock Holmes is a fictional detective created by Scottish author and physician Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. The fantastic London-based "consulting detective", Holmes is famous for his astute logical reasoning, his ability to take almost any disguise, and his use of forensic science skills to solve...

.

He was also involved in the case of the Brighton trunk murders

Brighton trunk murders

The Brighton trunk murders were two unrelated murders linked to Brighton, England in 1934. In both, the dismembered body of a murdered woman was placed in a trunk....

, and although the accused man, Mancini, in whose flat the body of a murdered prostitute was found, was acquitted at the trial, Mancini confessed to the killing just before his own death, many years later, so vindicating Spilsbury's evidence.

He was able to work with minimal remains, such as that involved in the "Blazing car murder", when a near destroyed body was found in the wreck of a burnt-out car near Northampton

Northampton

Northampton is a large market town and local government district in the East Midlands region of England. Situated about north-west of London and around south-east of Birmingham, Northampton lies on the River Nene and is the county town of Northamptonshire. The demonym of Northampton is...

in 1930. He gave evidence of how the man had died, although the victim was never identified, and so helped convict Alfred Rouse

Alfred Rouse

Alfred Arthur Rouse was a British murderer. It was theorised, though never proved, that Rouse, seeking to fabricate his own death, picked up a hitch-hiker, knocked him out, and then burnt his car with the man inside...

. During his career Spilsbury performed thousands of autopsies

Autopsy

An autopsy—also known as a post-mortem examination, necropsy , autopsia cadaverum, or obduction—is a highly specialized surgical procedure that consists of a thorough examination of a corpse to determine the cause and manner of death and to evaluate any disease or injury that may be present...

, not only for murder victims but also of executed criminals. He was able to appear for the defence in Scotland, where his status as a Home Office pathologist in England and Wales was irrelevant: he testified for the defence in the case of Donald Merrett, tried in February 1927 for the murder of his mother and acquitted as not proven

Not proven

Not proven is a verdict available to a court in Scotland.Under Scots law, a criminal trial may end in one of three verdicts: one of conviction and two of acquittal ....

.

Spilsbury was knighted

Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is an order of chivalry established on 4 June 1917 by George V of the United Kingdom. The Order comprises five classes in civil and military divisions...

in 1923. He was a Home Office

Home Office

The Home Office is the United Kingdom government department responsible for immigration control, security, and order. As such it is responsible for the police, UK Border Agency, and the Security Service . It is also in charge of government policy on security-related issues such as drugs,...

approved pathologist, lecturer in forensic medicine in the University College Hospital

University College Hospital

University College Hospital is a teaching hospital located in London, United Kingdom. It is part of the University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and is closely associated with University College London ....

, London School of Medicine for Women

London School of Medicine for Women

The London School of Medicine for Women was established in 1874 and was the first medical school in Britain to train women.The school was formed by an association of pioneering women physicians Sophia Jex-Blake, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, Emily Blackwell and Elizabeth Blackwell with Thomas Henry...

and St. Thomas' Hospital. He also was a Fellow of the Royal Society of Medicine

Royal Society of Medicine

The Royal Society of Medicine is a British charitable organisation whose main purpose is as a provider of medical education, running over 350 meetings and conferences each year.- History and overview :...

.

Files containing notes on deaths investigated by Spilsbury went under the hammer at Sotheby's on 17 July 2008, when they were acquired by the Wellcome Library

Wellcome Library

The Wellcome Library is founded on the collection formed by Sir Henry Wellcome , whose personal wealth allowed him to create one of the most ambitious collections of the 20th century. Henry Wellcome's interest was the history of medicine in a broad sense and included subjects like alchemy or...

in London. The index card

Index card

An index card consists of heavy paper stock cut to a standard size, used for recording and storing small amounts of discrete data. It was invented by Carl Linnaeus, around 1760....

s documented deaths in London and the Home Counties from 1905 to 1932. The hand-written cards, discovered in a lost cabinet, were the notes that Spilsbury apparently accumulated for a textbook on forensic medicine which he was planning, but there is no evidence that he ever started the book.

Media

On 12 June 2008 BBCBBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation is a British public service broadcaster. Its headquarters is at Broadcasting House in the City of Westminster, London. It is the largest broadcaster in the world, with about 23,000 staff...

Radio 4's afternoon play The Incomparable Witness by Nichola McAuliffe

Nichola McAuliffe

Nichola McAuliffe is an English television and stage actress and writer, best known for her role as Sheila Sabatini in the sitcom Surgical Spirit.-Background:McAuliffe was born in 1955 in Surrey, England...

was a drama about Sir Bernard Spilsbury, 'the father of modern forensics'.

Spilsbury was commemorated by an English Heritage

English Heritage

English Heritage . is an executive non-departmental public body of the British Government sponsored by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport...

Blue plaque

Blue plaque

A blue plaque is a permanent sign installed in a public place to commemorate a link between that location and a famous person or event, serving as a historical marker....

attached to his former home at Marlborough Hill, London, NW8

Posthumous reputation

In recent years, there has been some reassessment of Spilsbury's reputation which has raised questions over his degree of objectivity. An article in the British Medical JournalBritish Medical Journal

BMJ is a partially open-access peer-reviewed medical journal. Originally called the British Medical Journal, the title was officially shortened to BMJ in 1988. The journal is published by the BMJ Group, a wholly owned subsidiary of the British Medical Association...

noted how "the virtuosity" of Spilsbury's performances in the mortuary and the courtroom "threatened to undermine the foundations of forensic pathology as a modern and objective specialism". Spilsbury is particularly criticised for his insistence on working alone; a refusal to train students; and an unwillingness to engage in academic research or peer review. This, says the article's author, "lent him an aura of infallibility that for many raised concerns that it was his celebrity rather than his science that persuaded juries to credit his evidence over all others."

Sources

- Jane Robins - The Magnificent Spilsbury and the Case of the Brides in the Bath (2010) John Murray

- Douglas Browne and E. V. Tullett - Bernard Spilsbury: His Life and Cases (1951)

- Colin Evans - the Father of Forensics

- J.H.H. Gaute and Robin Odell - The New Murderer's Who's Who, 1996, Harrap Books, London

- Andrew Rose "Lethal Witness" Sutton Publishing 2007 - also to be published in the US by Kent State University Press