Brethren of Purity

Encyclopedia

Secret society

A secret society is a club or organization whose activities and inner functioning are concealed from non-members. The society may or may not attempt to conceal its existence. The term usually excludes covert groups, such as intelligence agencies or guerrilla insurgencies, which hide their...

of Muslim philosophers

Early Islamic philosophy

Early Islamic philosophy or classical Islamic philosophy is a period of intense philosophical development beginning in the 2nd century AH of the Islamic calendar and lasting until the 6th century AH...

in Basra

Basra

Basra is the capital of Basra Governorate, in southern Iraq near Kuwait and Iran. It had an estimated population of two million as of 2009...

, Iraq

Iraq

Iraq ; officially the Republic of Iraq is a country in Western Asia spanning most of the northwestern end of the Zagros mountain range, the eastern part of the Syrian Desert and the northern part of the Arabian Desert....

, in the 10th century CE

Common Era

Common Era ,abbreviated as CE, is an alternative designation for the calendar era originally introduced by Dionysius Exiguus in the 6th century, traditionally identified with Anno Domini .Dates before the year 1 CE are indicated by the usage of BCE, short for Before the Common Era Common Era...

.

The structure of this mysterious organization and the identities of its members have never been clear.

Their esoteric

Esotericism

Esotericism or Esoterism signifies the holding of esoteric opinions or beliefs, that is, ideas preserved or understood by a small group or those specially initiated, or of rare or unusual interest. The term derives from the Greek , a compound of : "within", thus "pertaining to the more inward",...

teachings and philosophy are expounded in an epistolary

Epistolary novel

An epistolary novel is a novel written as a series of documents. The usual form is letters, although diary entries, newspaper clippings and other documents are sometimes used. Recently, electronic "documents" such as recordings and radio, blogs, and e-mails have also come into use...

style in the Encyclopedia of the Brethren of Purity

Encyclopedia of the Brethren of Purity

The Encyclopedia of the Brethren of Purity was a large encyclopedia in 52 treatises written by the mysterious Brethren of Purity of Basra, Iraq sometime in the second half of the 10th century CE...

(Arabic:

Name

The Arabic "Ikhwan al-Safa" (short for, among many possible transcriptions, "Ikhwan al-Safa wa Khullan al-Wafa wa Ahl al-Hamd wa abna al-Majd", or the "Brethren of Purity, Loyal Friends, People worthy of praise and Sons of Glory") can be translated as either the "Brethren of Purity" or the "Brethren of Sincerity"; various scholars such as Ian Netton prefer "of Purity" because of the group's ascetic impulses towards purity and salvation.A suggestion made by Goldziher, and later written about by Philip K. Hitti in his History of Arabs, is that the name is taken from a story in Kalilah wa-Dimnah, in which a group of animals, by acting as faithful friends (ikhwan al-safa), escape the snares of the hunter. The story concerns a ring-dove and its companions who get entangled in the net of a hunter seeking birds. Together, they leave themselves and the ensnaring net to a nearby rat

Rat

Rats are various medium-sized, long-tailed rodents of the superfamily Muroidea. "True rats" are members of the genus Rattus, the most important of which to humans are the black rat, Rattus rattus, and the brown rat, Rattus norvegicus...

, who is gracious enough to gnaw the birds free of the net; impressed by the rat's altruistic deed, a crow

Crow

Crows form the genus Corvus in the family Corvidae. Ranging in size from the relatively small pigeon-size jackdaws to the Common Raven of the Holarctic region and Thick-billed Raven of the highlands of Ethiopia, the 40 or so members of this genus occur on all temperate continents and several...

becomes the rat's friend. Soon a tortoise

Tortoise

Tortoises are a family of land-dwelling reptiles of the order of turtles . Like their marine cousins, the sea turtles, tortoises are shielded from predators by a shell. The top part of the shell is the carapace, the underside is the plastron, and the two are connected by the bridge. The tortoise...

and gazelle

Gazelle

A gazelle is any of many antelope species in the genus Gazella, or formerly considered to belong to it. Six species are included in two genera, Eudorcas and Nanger, which were formerly considered subgenera...

also join the company of animals. After some time, the gazelle is trapped by another net; with the aid of the others and the good rat, the gazelle is soon freed, but the tortoise fails to leave swiftly enough and is himself captured by the hunter. In the final turn of events, the gazelle repays the tortoise by serving as a decoy and distracting the hunter while the rat and the others free the tortoise. After this, the animals are designated as the "Ikwhan al-Safa".

This story is mentioned as an exemplum

Exemplum

An exemplum is a moral anecdote, brief or extended, real or fictitious, used to illustrate a point.-Exemplary literature:...

when the Brethren speak of mutual aid in one rasa'il, a crucial part of their system of ethics that has been summarized thus:

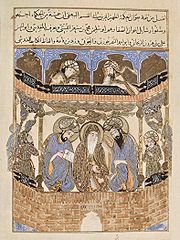

Meetings

The Brethren regularly met on a fixed schedule. The meetings apparently took place on three evenings of each month: once near the beginning, in which speeches were given, another towards the middle, apparently concerning astronomy and astrology, and the third between the end of the month and the 25th of that month; during the third one, they recited hymnHymn

A hymn is a type of song, usually religious, specifically written for the purpose of praise, adoration or prayer, and typically addressed to a deity or deities, or to a prominent figure or personification...

s with philosophical content . During their meetings and possibly also during the three feasts they held, on the dates of the sun's entry into the Zodiac signs "Ram, Cancer, and Balance"), besides the usual lectures and discussions, they would engage in some manner of liturgy

Liturgy

Liturgy is either the customary public worship done by a specific religious group, according to its particular traditions or a more precise term that distinguishes between those religious groups who believe their ritual requires the "people" to do the "work" of responding to the priest, and those...

reminiscent of the Harran

Harran

Harran was a major ancient city in Upper Mesopotamia whose site is near the modern village of Altınbaşak, Turkey, 24 miles southeast of Şanlıurfa...

ians

Ranks

HierarchyHierarchy

A hierarchy is an arrangement of items in which the items are represented as being "above," "below," or "at the same level as" one another...

was a major theme in their Encyclopedia, and unsurprisingly, the Brethren loosely divided themselves up into four ranks by age; the age guidelines would not have been firm, as for example, such an exemplar of the fourth rank as Jesus would have been too young if the age guidelines were absolute and fixed. Compare the similar division of the Encyclopedia into four sections and the Jabirite symbolism of 4. The ranks were:

- The "Craftsmen" – a craftsman had to be at least 15 years of age; their honorific was the "pious and compassionate" (al-abrār wa 'l-ruhamā).

- The "Political Leaders" – a political leader had to be at least 30 years of age; their honorific was the "good and excellent" (al-akhyār wa 'l-fudalā)

- The "Kings" – a king had to be at least 40 years of age; their honorific was the "excellent and noble" (al-fudalā' al-kirām)

- The "Prophets and Philosophers" – the most aspired-to, the final and highest rank of the Brethren; to become a Prophet or Philosopher a man had to be at least 50 years old; their honorific compared them to historical luminaries such as JesusJesusJesus of Nazareth , commonly referred to as Jesus Christ or simply as Jesus or Christ, is the central figure of Christianity...

, SocratesSocratesSocrates was a classical Greek Athenian philosopher. Credited as one of the founders of Western philosophy, he is an enigmatic figure known chiefly through the accounts of later classical writers, especially the writings of his students Plato and Xenophon, and the plays of his contemporary ...

, or MuhammadMuhammadMuhammad |ligature]] at U+FDF4 ;Arabic pronunciation varies regionally; the first vowel ranges from ~~; the second and the last vowel: ~~~. There are dialects which have no stress. In Egypt, it is pronounced not in religious contexts...

who were also classified as Kings; this rank was the "angelic rank" (al-martabat al-malakiyya).

Ismaili

Among the Isma'ili groups and missionaries who favored the Encyclopedia (as Paul Casanova shows in his 1898 work attempting to date the Brethren), authorship was sometimes ascribed to one or another "Hidden Imam"; this theory is recounted in Ibn al-Qifti's biographical compendium of philosophers and doctors, the "Chronicle of the Learned" (Ahkbār al-Hukamā or Tabaqāt-al-Hukamā).The compiler of Ikhwan as-Safa concealed his identity so skillfully that modern scholarship has spilled much ink in trying to trace the members of group. Using vivid metaphor, the members referred to themselves as "sleepers in the cave" (Rasail 4th, p. 18). In one place they gave as their reason for hiding their secrets from the people, not fear of earthly rulers nor trouble from the common populace, but a desire to protect their God-given gifts (Rasail 4th, p. 166). Yet they were well aware that their esoteric teachings might provoke unrest, and the calamities suffered by the successors of the Prophet were a good reason to remain hidden until the right day came for them to emerge from their cave and wake from their long sleep (Rasail 4th, p. 269). To live safely, it was necessary for their doctrines to be cloaked. Ian Richard Netton, however writes in "MusIim Neoplatonists" (London, 1982, p. 80) that, "The Ikhwan's concepts of exegesis of both Quran and Islamic tradition were tinged with the esoterism of the Ismailis." Strangely enough, in dealing with the doctrines of Qadariya and Sabaeans of Harran, the Epistles do not mention the Ismailism. Yet it was the Ismailis, perhaps more than any other, which had the most profound effect on the structure and vocabulary of the Epistles. Almost the average scholars have attempted to show that the Ikhwan (brothers) were definitely Ismailis. A.A.A. Fyzee,born and died a sulaimani , (1899–1981), for instance, writes in "Religion in the Middle East", (ed. by A.J. Arberry, Cambridge, 1969, 2nd vol., p. 324) that, "The tracts are clearly of Ismaili origin; and all authorities, ancient and modern, are agreed that the Rasail constitute the most authoritative exposition of the early form of the Ismaili religion." According to Yves Marquet, "It seems indisputable that the Epistles represent the state of Ismaili doctrine at the time of their compositions" (vide, "Encyclopaedia of Islam", 1960, p. 1071) Bernard Lewis in "The Origins of Ismailism" (London, 1940, p. 44) was more cautious than Fyzee, ranking the Epistles among books which, though "closely related to Ismailism" may not actually have been Ismaili, despite their batini inspiration. Ibn Qifti (d.646/1248), reporting in the 7th/13th century in "Tarikh-i Hukama" (p. 82) that, "Opinions differed about the authors of the Epistles. Some people attributed to an Alid Imam, proffering various names, whereas other put forward as author some early Mutazalite theologians."

Among the Syrian Ismailis, the earliest reference of the Epistles and its relation with the Ismailis is given in "Kitab Fusul wa'l Akhbar" by Nurudin bin Ahmad (d. 233/849). Another important work, "al-Usul wa'l-Ahakam" by Abul Ma'ali Hatim bin Imran bin Zuhra (d. 498/1104), quoted by Arif Tamir in "Khams Rasa'il Ismailiyya" (Salamia, 1956, p. 120), writes that, "These dais, and other dais with them, collaborated in composing long Epistles, fifty-two in number, on various branches of learning." It implies the Epistles being the product of the joint efforts of the Ismaili dais.

Among the Yamenite traces, the earliest reference of the Epistles is found in "Sirat-i Ibn Hawshab" by Garar bin Mansur al-Yamen, who lived between 270/883 and 360/970, and writes, "He (Imam Taqi Muhammad) went through many a difficulty and fear and the destruction of his family, whose description cannot be lengthier, until he issued (ansa'a) the Epistles and was contacted by a man called Abu Gafir from among his dais. He charged him with the mission as was necessary and asked him to keep his identity concealed." This source not only asserts the connection of the Epistles with the Ismailis, but also indicates that the Imam himself was not the sole author (sahibor mu'allif), but only the issuer or presenter (al-munsi). It suggests that the text of the philosophical deliberations was given a final touching by the Imam, and the approved text was delivered to Abu Gafir to be forwarded possibly to the Ikhwan in Basra secretly. Since the orthodox circles and the ruling power had portrayed a wrong image of Ismailism, the names of the compilers were concealed. The prominent members of the secret association seem to be however, Abul Hasan al-Tirmizi, Abdullah bin Mubarak, Abdullah bin Hamdan, Abdullah bin Maymun, Sa'id bin Hussain etc. The other Yamenite source connecting the Epistles with the Ismailis was the writing of Sayyadna Ibrahim bin al-Hussain al-Hamidi (d. 557/1162), who wrote "Kanz ul-Walad." After him, there followed "al-Anwar ul-Latifa" by Sayyadna Muhammad bin Tahir (d. 584/1188), "Tanbih al-Ghafilin" by Sayyadna Hatim bin Ibrahim Al Hamidi (d. 596/1199), "Damigh al-Batil wa hatf ul-Munaazil" by Sayyadna Ali bin Muhammad bin al-Walid al-Anf (d. 612/1215), "Risalat al-Waheeda" by Sayyadna Hussain bin Ali al-Anf (d. 667/1268) and "Uyun'ul-Akhbar" by Sayyadna Idris bin Hasan Imaduddin (d. 872/1468) etc.

According to "Ikhwan as-Safa" (Rasail 21st., p. 166), "Know, that among us there are kings, princes, khalifs, sultans, chiefs, ministers, administrators, tax agents, treasurers, officers, chamberlains, notables, nobles, servants of kings and their military supporters. Among us too there are merchants, artisans, agriculturists and stock breeders. There are builders, landowners, the worthy and wealthy, gentlefolk and possessors of all many virtues. We also have persons of culture, of science, of piety and of virtue. We have orators, poets, eloquent persons, theologians, grammarians, tellers of tales and purveyors of lore, narrators of traditions, readers, scholars, jurists, judges, magistrates and ecstatics. Among us too there are philosophers, sages, geometers, astronomers, naturalists, physicians, diviners, soothsayers, casters of spells and enchantments, interpreters of dreams, alchemists, astrologers, and many other sorts, too many to mention."

al-Tawhīdī

Al-Qifti, however, denigrates this account and instead turns to a comment he discovered, written by Abū Hayyān al-Tawhīdī (d. 1023) in his Kitāb al-Imtā' wa'l-Mu'ānasa (written between 983 and 985), a collection of 37 seances at the court of Ibn Sa'dān, vizierVizier

A vizier or in Arabic script ; ; sometimes spelled vazir, vizir, vasir, wazir, vesir, or vezir) is a high-ranking political advisor or minister in a Muslim government....

of the Buyid ruler Samsam ad-Dawla. Apparently, al-Tawhīdī was close to a certain Zaid b. Rifa'a, praising his intellect, ability and deep knowledge – indeed, he had dedicated his Kitāb as-Sadiq was-Sadaqa to Zaid – but he was disappointed that Zaid was not orthodox or consistent in his beliefs, and that he was, as Stern puts it:

For many years, this was the only account of the authors' identities, but al-Tawhīdī's comments were second-hand evidence and so unsatisfactory; further, the account is incomplete, as Abu Hayyan mentions that there were others besides these 4.

This situation lasted until al-Tawhīdī's Kitāb al-Imtā' wa'l-Mu'ānasa was published in 1942. This publication substantially supported al-Qifti's work, although al-Qifti apparently toned down the description and prominence of al-Tawhīdī's charges that the Brethren were Batiniyya

Batiniyya

Batiniyya is a pejorative term to refer to those groups, such as Alevism, Ismailism, and often Sufism, which distinguish between an inner, esoteric level of meaning in the Qur'an, in addition to the outer, exoteric level of meaning Zahiri...

, an esoteric Ismaili sect and thus heretics, possibly so as to not tar his friend Zaid with the same brush.

Stern derives a further result from the published text of the Kitāb al-Imtā 'wal-Muanasa, pointing out that a story al-Tawhīdī ascribes to a personal meeting with Qādī Abu'l-Hasan 'Alī b. Hārūn az-Zanjāni, the founder of the group, appears in almost identical form in one of the epistles. While neat, Stern's view of things has been challenged by Tibawi, who points out some assumptions and errors Stern has made, such as the relationship between the story in al-Tawhīdī's work and the Epistles; Tibawi points out the possibility that the story was instead taken from a third, independent and prior source.

al-Tawhīdī's testimony has also been described as thus:

The last contemporary source comes from the surviving portions of the Kitāb Siwan al-Hikma (c. 950) by Abu Sulaiman al-Mantiqi (al-Tawhīdī's teacher; 912-985), which was a sort of compendium of biographies; al-Mantiqi is primarily interested in the Brethren's literary techniques of using parables and stories, and so he says only this little before proceeding to give some extracts of the Encyclopedia:

al-Maqdisī was previously listed in the Basra group of al-Tawhīdī; here Stern and Hamdani differ, with Stern quoting Mantiqi as crediting Maqdisi with 52 epistles, but Hamdani says "By the time of al-Manṭiqī, the Rasā'īl were almost complete (he mentions 51 tracts)."

The second near-contemporary record is another comment by Shahzúry or (Shahrazūrī) as recorded in the Tawārikh al-Hukamā or alternatively, the Tawárykh al-Hokamá; specifically, it is from the Nuzhat al-arwah, which is contained in the Tawárykh, which states:

Hamdani disputes the general abovegoing identifications, pointing out that accounts differ in multiple details, such as whether Zayd was an author or not, whether there was a principal author, and who was in the group or not. He lays particular stress on quotes from the Encyclopedia dating between 954 and 960 in the anonymous (Pseudo-Majriti) work Ghāyat al-Hakīm; al-Maqdisi and al-Zanjani are known to have been active in 983, He finds it implausible they would have written or edited "so large an encyclopedia at least twenty-five to thirty years earlier, that is, around 343/954 to 348/960, when they would have been very young." He explains the al-Tawhidi narrative as being motivated by contemporary politics and issues of hereticism relating to the Qarmatians

Qarmatians

The Qarmatians were a Shi'a Ismaili group centered in eastern Arabia, where they attempted to established a utopian republic in 899 CE. They are most famed for their revolt against the Abbasid Caliphate...

, and points out that there is proof that Abu Hayyan has fabricated other messages and information.

Amusingly, Aloys Sprenger

Aloys Sprenger

Aloys Sprenger was an Austrian orientalist.Sprenger studied medicine, natural sciences as well as oriental languages at the University of Vienna...

mentions this in a footnote:

The Epistles of the Brethren of Purity

The Rasa’il Ikhwan al-Safa’ (Epistles of the Brethren of Purity) consist of fifty-two treatises in mathematics, natural sciences, psychology (psychical sciences) and theology. The first part, which is on mathematics, groups fourteen epistles that include treatises in arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, geography, and music, along with tracts in elementary logic, inclusive of: the Isagoge, the Categories, De Interpretatione, the Prior Analytics and the Posterior Analytics. The second part, which is on natural sciences, gathers seventeen epistles on matter and form, generation and corruption, metallurgy, meteorology, a study of the essence of nature, the classes of plants and animals, including a fable. The third part, which is on psychology, comprises ten epistles on the psychical and intellective sciences, dealing with the nature of the intellect and the intelligible, the symbolism of temporal cycles, the mystical essence of love, resurrection, causes and effects, definitions and descriptions. The fourth part deals with theology in eleven epistles, investigating the varieties of religious sects, the virtue of the companionship of the Brethren of Purity, the properties of genuine belief, the nature of the Divine Law, the species of politics, and the essence of magic.http://www.iis.ac.uk/view_article.asp?ContentID=105218They define a perfect man in their Rasa'il as "of East Persian derivation, of Arabic faith, of Iraqi, that is Babylonian, in education, Hebrew in astuteness, a disciple of Christ in conduct, as pious as a Syrian monk, a Greek in natural sciences, an Indian in the interpretation of mysteries and, above all a Sufi or a mystic in his whole spiritual outlook". There are debates on using this description and other materials of Rasa'il that could help with determination of the identity, affiliation (with Ismaili, Sufism, ...), and other characteristics of Ikhwan al-Safa.

The Rasa’il Ikhwan al-Safa’ are available in print through a variety of Arabic editions, starting from the version established in Calcutta in 1812, then followed by the edition of Bombay of 1887–1889), then by the edition of Khayr al-Din al-Zirikli in 1928 in Cairo, and the Beirut Sadir edition by Butrus Bustani in 1957 and the version set by ‘Arif Tamir in Beirut in 1995. All these editions are not critical and we do not yet have a complete English translation of the whole Rasa’il encyclopedia.

The first complete Arabic critical edition and fully annotated English translation of the Rasa’il Ikhwan al-Safa’ is being prepared for publication by a team of editors, translators and scholars as part of a book series that is published by Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press is the largest university press in the world. It is a department of the University of Oxford and is governed by a group of 15 academics appointed by the Vice-Chancellor known as the Delegates of the Press. They are headed by the Secretary to the Delegates, who serves as...

in association with the Institute of Ismaili Studies in London; a project currently coordinated by the series General Editor Nader El-Bizri

Nader El-Bizri

Nader El-Bizri is a Lebanese philosopher, historian of science, and architect living in Britain.-Intellectual Profile:...

.http://www.iis.ac.uk/view_person.asp?ID=100138&type=user This series is initiated by an introductory volume of studies edited by Nader El-Bizri

Nader El-Bizri

Nader El-Bizri is a Lebanese philosopher, historian of science, and architect living in Britain.-Intellectual Profile:...

, which was published by Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press is the largest university press in the world. It is a department of the University of Oxford and is governed by a group of 15 academics appointed by the Vice-Chancellor known as the Delegates of the Press. They are headed by the Secretary to the Delegates, who serves as...

in 2008, and followed in 2009 by the voluminous Arabic critical edition and annotated English translation with commentaries of The Case of the Animals Versus Man Before the King of the Jinn (Epistle 22).http://www.oup.com/uk/catalogue/?ci=9780199557240

External links

(PDF version).- http://ismaili.net/histoire/history04/history428.html

- Article at the Encyclopædia BritannicaEncyclopædia BritannicaThe Encyclopædia Britannica , published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., is a general knowledge English-language encyclopaedia that is available in print, as a DVD, and on the Internet. It is written and continuously updated by about 100 full-time editors and more than 4,000 expert...

- "Ikhwanus Safa: A Rational and Liberal Approach to Islam" – (by Asghar Ali Engineer)

- "The Classification of the Sciences according to the Rasa'il Ikhwan al-Safa'" by Godefroid de Callataÿ

- The Institute of Ismaili Studies article on the Brethren, by Nader El-Bizri

- The Institute of Ismaili Studies gallery of images of manuscripts of the Rasa’il of the Ikhwan al-Safa’

- Article in Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy