Bunyip aristocracy

Encyclopedia

It was first coined in 1853 by Daniel Deniehy

Daniel Deniehy

Daniel Henry Deniehy was an Australian journalist, orator and politician; and early advocate of democracy in colonial New South Wales.-Early life:...

who made a speech lambasting the attempt by William Wentworth

William Wentworth

William Charles Wentworth was an Australian poet, explorer, journalist and politician, and one of the leading figures of early colonial New South Wales...

to establish a titled aristocracy

Aristocracy

Aristocracy , is a form of government in which a few elite citizens rule. The term derives from the Greek aristokratia, meaning "rule of the best". In origin in Ancient Greece, it was conceived of as rule by the best qualified citizens, and contrasted with monarchy...

in the New South Wales

New South Wales

New South Wales is a state of :Australia, located in the east of the country. It is bordered by Queensland, Victoria and South Australia to the north, south and west respectively. To the east, the state is bordered by the Tasman Sea, which forms part of the Pacific Ocean. New South Wales...

government. This speech came to be known as the Bunyip Aristocracy speech.

Deniehy made speeches opposing the new self titled Australian aristocracy in the Victorian theatre and on the soapbox

Soapbox

A soapbox is a raised platform on which one stands to make an impromptu speech, often about a political subject. The term originates from the days when speakers would elevate themselves by standing on a wooden crate originally used for shipment of soap or other dry goods from a manufacturer to a...

at Circular Quay.

In response to Wentworth's proposal to create an hereditary peerage

Peerage

The Peerage is a legal system of largely hereditary titles in the United Kingdom, which constitute the ranks of British nobility and is part of the British honours system...

in New South Wales, Deniehy's satirical comments included: "Here, we all know the common water mole was transferred into the duck-billed platypus

Platypus

The platypus is a semi-aquatic mammal endemic to eastern Australia, including Tasmania. Together with the four species of echidna, it is one of the five extant species of monotremes, the only mammals that lay eggs instead of giving birth to live young...

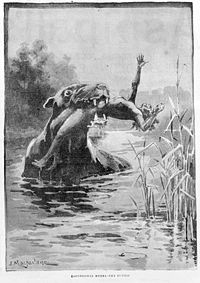

, and in some distant emulation of this degeneration, I suppose we are to be favoured with a "bunyip aristocracy." (The bunyip

Bunyip

The bunyip, or kianpraty, is a large mythical creature from Aboriginal mythology, said to lurk in swamps, billabongs, creeks, riverbeds, and waterholes....

is an Ancestral Being of Aboriginal Dreaming.) Deniehy's ridicule caused the idea to be dropped.

Among those singled out in his speech by Deniehy was James MacArthur (1798–1867), the son of John MacArthur

John Macarthur (wool pioneer)

John Macarthur was a British army officer, entrepreneur, politician, architect and pioneer of settlement in Australia. Macarthur is recognised as the pioneer of the wool industry that was to boom in Australia in the early 19th century and become a trademark of the nation...

, who had been nominated to the New South Wales Legislative Council

New South Wales Legislative Council

The New South Wales Legislative Council, or upper house, is one of the two chambers of the parliament of New South Wales in Australia. The other is the Legislative Assembly. Both sit at Parliament House in the state capital, Sydney. The Assembly is referred to as the lower house and the Council as...

in 1839 and was later (1859) elected to the New South Wales Legislative Assembly

New South Wales Legislative Assembly

The Legislative Assembly, or lower house, is one of the two chambers of the Parliament of New South Wales, an Australian state. The other chamber is the Legislative Council. Both the Assembly and Council sit at Parliament House in the state capital, Sydney...

(the lower house was only created in 1856):

Next came the native aristocrat James MacArthur, he would he supposed, aspire to the coronet of an earl, he would call him the Earl of Camden, and he suggests for his coat of arms a field vert, the heraldic term for green, and emblazoned on this field should be a rum keg of a New South Wales order of chivalry.

The strong popular support for Deniehy's views caused the abandonment of the proposal he was responding to. It probably also delayed the introduction of an Australian honours system. The Order of Australia

Order of Australia

The Order of Australia is an order of chivalry established on 14 February 1975 by Elizabeth II, Queen of Australia, "for the purpose of according recognition to Australian citizens and other persons for achievement or for meritorious service"...

was not introduced until 1975. Until that time Australians were awarded British honours

British honours system

The British honours system is a means of rewarding individuals' personal bravery, achievement, or service to the United Kingdom and the British Overseas Territories...

.

'Bunyip aristocracy' is now an offensive term or an insult used to refer to those Australians who consider themselves to be aristocrats.

Dan Deniehy's Bunyip aristocracy speech

Note: Deniehy had a habit of writing speeches and articles that addressed himself in the third personMr. Deniehy seconded the resolution [that this meeting pledges itself to resist, by every constitutional means in its power, the formation of a second chamber which is not based on popular suffrage]. Why he had been selected to speak to the present resolution he knew not, save that as a native of the colony he might naturally be expected to feel something like real interest, and to speak with something like real feeling on a question connected with the political institutions of the country. He would do his best to respond to that invitation 'Speak up,' and would perhaps balance deficiencies flowing from a small volume of voice by in all cases calling things by their right names.

He protested against the present daring and unheard-of attempt to tamper with a fundamental popular right - that of having a voice in the nomination of men who were to make, or control the making of, laws binding on the community - laws perpetually shifting and changing the nature of the whole social economy of a given state, and frequently operating in the subtlest forms on the very dearest interests of the citizen - on his domestic, his moral, perhaps his religious relations.

The name of Mr. Wentworth had frequently been mentioned there that day, and that on one or two occasions with an unwise tenderness, a squeamish reluctance to speak plain, English , and call certain nasty doings of Mr. Wentworth by the usual homely appellatives, simply because they were Mr. Wentworth's. He for one was nowise disposed, as preceding speakers had seemed, in tapping the vast shoulder of Mr. Wentworth's political recreancies, to 'damn him with faint praise

Damn with faint praise

Damn with faint praise is an English idiom for words that effectively condemn by seeming to offer praise which is too moderate or marginal to be considered praise at all...

and mistimed eulogy.

He had listened from boyhood upwards to grey tradition, Mr. Wentworth's demagogic Areopagitas - his speeches for the liberty of unlicensed printing regime of Darling; and for these and divers other deeds of a time when the honourable member for Sydney had to the full his share of the chivalrous pugnacities of five-and-twenty, he was as much disposed to give Mr Wentworth credit as any man. But with these perpetual fantasies, these everlasting variations on the 'Light of the other Days,' continually ringing in his ears, he [Dan Deniehy] was fain to enquire by what rule of moral and political appraisal, it was sought to throw in a scale opposite to that containing the flagrant and shameless political dishonesty of years, the democratic escapades, sins long since repented of in early youth.

The subsequent political conduct-rather the systemic political principles of Mr. Wentworth - had been such as would have been sufficient to cancel the value of even a century of action. The British Constitution had been frequently spoken of that afternoon in terms of unbounded laudation. That Constitution certainly deserved to be spoken of with respect; he [Dan Deniehy] respected it, no doubt they all respected it.

But his was a qualified respect at best, and in all presumed assimilations of the political hypotheses of our colonial Constitution-makers with the Constitution of Great Britain, he warned them not be seduced by mere words and phrases-sheer 'talkee talkee.' Relatively, it was not only an admirable example of slowly growing and gradually elaborated political experience, applied, set in action, but it was also eminent and exemplary as a long history, still evolving, of political philosophy. But it was after all but relatively good for its wonderfully successful fusion of principles the most antagonistic.

Circumstances entirely alter cases, and he would warn them to be seduced by no mere vague association exhaled from the use of venerable phrases, that had, what phrases now-a-days seldom could boast, genuine meanings attached to them. The patrician element existed in the British Constitution as did the regal, for good reasons-it had stood in the way of all late legislatorial thought and operation as a great fact; as such it was handled, and in a deep and prudential spirit of conservatism allowed to stand-but as affecting the basis and foundation of the architecture of a Constitution-the elective principle neutralised for all detrimental influence, by conversion, practically, into a mere check upon the deliberations of the initiative section of the Legislature.

And having the right to frame, to embody, to shape it as we would, with no great stubborn facts to work upon as in England, there was nothing but the elective principle and the inalienable freedom of every colonist upon which to work out the whole organisation and body of our political institution.

But because it was the good pleasure of Mr. Wentworth and the respectable tail of that puissant Legislative body, whose serpentine movements were so ridiculous, we were not to form our own Constitution, but instead of this we were to have an Upper House and a Constitution cast upon us, upon a pattern which should suit the taste and propriety of political oligarchs who treated the people at large as if they were cattle to be bought and sold in the market; or as they indeed were in American slave States, and now in Australian markets, where we might find bamboozled coolies and kidnapped Chinamen.

And being in a figurative humour, he might endeavour to make some of the proposed nobility to pass before the stage of our imagination, as the ghost of Banquo walked along in the vision of Macbeth, so that we might have a fair view of these Harlequin aristocrats, these Botany Bay magnificos (laughter), these Australian mandarins.

Let them walk across the stage in all the pomp and circumstances of hereditary titles. First, then, in the procession stalks the hoary Wentworth. But he could not imagine that to such a head the strawberry leaves [a reference to the decoration on a Duke's coronet] would add any honour.

Next came the native aristocrat Mr. James Macarthur, he would he supposed, aspire to the coronet of an earl, he would call him the Earl of Camden, and he suggests for his coat of arms a field vert, the heraldic term for green- (great cheers and laughter) -and emblazoned on this field should be a rum keg of a New South Wales order of chivalry. There was also the colonial starred Terence Aubrey Murray, with more crosses and orders-not perhaps orders of merit-than a state of mandarinhood.

Another friend who claimed a colonial title was George Robert Nichols, the hereditary Grand Chancellor of all the Australias. Behold him in the serene and moody dignity of that portrait of Rodius' that smiled on us in all the public - house parlours - the gentleman who took Mr. Lowe to task for altering his opinions; this conqueror in the lists of jaw, and the victor in the realms of gab. It might be well to ridicule the doings of such a clique, but their doings merited burning indignation-yet, to speak seriously of such a project would too much resemble the Irishman's kicking at nothing, it wrenched one horribly.

But, though their weakness was ridiculous, he could assure them that these pygmies might do a great deal of mischief. They would bring contempt on a country whose interest he was sure they all had at heart, until even the poor Irishman in the streets of Dublin would fling his jibe at the Botany Bay aristocrats. In fact, he was puzzled how to classify them. They could not aspire to the miserable and effete dignity of the grandees of Spain.

They had antiquity of birth, but these he would defy any naturalist properly to classify them. But perhaps it was only a specimen of the remarkable contrariety that existed at the Antipodes. Here they all know the common water mole was transferred into the duck-billed platypus, and in some distant emulations of this degeneration, he supposed they were to be favoured with a bunyip aristocracy.

He trusted that this was only the beginning of a more extended movement, and from its auspicious commencement he augured the happiest results. A more orderly, united, and consolidated movement he had never witnessed. He must say that he was proud to belong to Botany Bay.

He took it as no term of reproach, when he saw that there was such a keen sensibility on the subject of their political sights - that the instant the liberties of their country were threatened, they could assemble, and with one voice, declare their determined and undying opposition.

But he would remind them that this was not a selfish consideration, there were wider interests at stake. In the present disturbed state of Europe, they must calculate on having to receive the poor Russian flying from the knout

Knout

A knout is a heavy scourge-like multiple whip, usually made of a bunch of rawhide thongs attached to a long handle, sometimes with metal wire or hooks incorporated....

of his oppressor.

And also, looking at the gradually increasing pressure of political parties at home, they must prepare to open their arms and receive the fugitives from England, Scotland, and Ireland, who would hasten to gain a security and a competence, that appeared to be denied them in their own country.

The interests of these countless thousands were involved in their decision on this occasion, and they looked, and were entitled to look, for a heritage befitting the dignity of free men. Bring them not here with delusive hopes-let them not find a new-fangled aristocracy haunting these free shores.

But it is to yours to offer them a land, where man is rewarded for his labour, and where the law no more recognises the supremacy of a class, than it recognises the predominance of a religion. But there is an aristocracy worthy of our ambition. Wherever man's skill is eminent, wherever glorious manhood asserts its elevation, there is an aristocracy that confers honour on the land that possesses it. That is God's aristocracy.

That is an aristocracy that will grow and expand under free institutions, and bless the land where it flourishes. He hoped they would take into consideration the hitherto barren condition of the country they were legislating for. He was a native of this young but glorious continent. Its past was not hallowed in history by the achievements of men whose names reflected a light on the times in which they lived. They had no long line of poets, of statesmen, and warriors; in this country art had done nothing, but nature everything. It was theirs to inaugurate the future.

In no country had the attempt been successfully made to manufacture an aristocracy pro re nata. It could not be done. They might as well expect honour to be paid to the nobles of King Kamehameha, or the ebony earls of the Emperor Soulouque of Hayti.

The aristocracy of England was founded on the sword. The men that came over with William the Conqueror were the masters of the Saxons, and so were the aristocracy. The soldiers of Cromwell were the masters of the Irish, and so became their aristocracy. But he should like to know how Wentworth and his clique had conquered the inhabitants of New South Wales - except in the artful dodgery of doctoring up a Franchise Bill.

If we were to be blessed with an aristocracy he would rather it should not resemble that of William the Bastard but of Jack the Strapper.

But he trespassed too long on their time and would only seek in conclusion, but to record two things. First, his indignant denunciation of any tampering with the purity of the elective principle, the only basis upon which good government could be placed; and, secondly, he wished them to regard the future destinies of their country.

Let them, with prophetic eye, behold the troops of weary pilgrims, from foreign despotism, which would, ere long, be floating to their shores, and let them now - give the most earnest assurance, that such men as composed the Wentworth clique, were not the representations of the spirit, the intelligence, of the freemen of New South Wales.

Colonial peerage

A Committee, consisting of Messrs. Charles Cowper, T.A. Murray, George Macleay, E. Dea-Thomson, J.H. Plunkett, Dr. Douglas, W. Thurlow, James Macarthur, James Martin, and W.C. Wentworth, appointed on the motion of W.C.Wentworth, held its first meeting, Sydney, May 27, 1853. Fifteen meetings were called. Half the members did not attend the meetings. The Bill was reported 28 July 1853. It was almost universally condemned by the people and a large public meeting was called to oppose it. In the advertisement convening the meeting were the following paragraphs :- A committee of the Legislative Council has framed a new Constitution for the colony, by which it is proposed

- (1.) To create a colonial nobility with hereditary privileges.

- (2.) To construct an Upper House of Legislature in which the people will have no voice.

- (3.) To add eighteen new seats to the Lower House, only one of which is to be allotted to Sydney while the other seventeen are to be allotted among the country and squatting districts.

- (4.) To squander the public revenue by pensioning off the officers of the Government on their full salaries ! thus implanting in our institutions a principle of jobbery and corruption.

- (5.) To fix irrevocably on the people this oligarchy in the name of free institutions so that no future Legislature can reform it even by absolute majority. The Legislative Council has the hardihood to propose passing this unconstitutional and anti-British measure with only a few days notice, and before it can possibly be considered by the colonists at large." The meeting was addressed by Sir Henry Parkes and other Liberals, and the result of the agitation was that the most objectionable clause, to create an hereditary colonial peerage, was struck out.