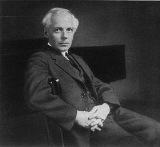

Béla Bartók

Encyclopedia

Franz Liszt

Franz Liszt ; ), was a 19th-century Hungarian composer, pianist, conductor, and teacher.Liszt became renowned in Europe during the nineteenth century for his virtuosic skill as a pianist. He was said by his contemporaries to have been the most technically advanced pianist of his age...

, as Hungary's greatest composer (Gillies 2001). Through his collection and analytical study of folk music

Folk music

Folk music is an English term encompassing both traditional folk music and contemporary folk music. The term originated in the 19th century. Traditional folk music has been defined in several ways: as music transmitted by mouth, as music of the lower classes, and as music with unknown composers....

, he was one of the founders of ethnomusicology

Ethnomusicology

Ethnomusicology is defined as "the study of social and cultural aspects of music and dance in local and global contexts."Coined by the musician Jaap Kunst from the Greek words ἔθνος ethnos and μουσική mousike , it is often considered the anthropology or ethnography of music...

.

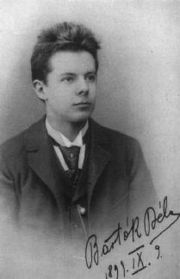

Childhood and early years (1881–98)

Béla Bartók was born in the small BanatBanat

The Banat is a geographical and historical region in Central Europe currently divided between three countries: the eastern part lies in western Romania , the western part in northeastern Serbia , and a small...

ian town of Nagyszentmiklós in the Kingdom of Hungary

Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary comprised present-day Hungary, Slovakia and Croatia , Transylvania , Carpatho Ruthenia , Vojvodina , Burgenland , and other smaller territories surrounding present-day Hungary's borders...

, Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary , more formally known as the Kingdoms and Lands Represented in the Imperial Council and the Lands of the Holy Hungarian Crown of Saint Stephen, was a constitutional monarchic union between the crowns of the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary in...

(since 1920 Sânnicolau Mare

Sânnicolau Mare

Sânnicolau Mare is a town in Timiş County, Romania and the westernmost of the country. Located in the Banat region, along the borders with Serbia and Hungary, it has a population of just under 13,000...

, Romania) on March 25, 1881. Bartók's family reflected some of the ethno-cultural diversities of the country. His father, Béla Sr., considered himself thoroughly Hungarian, because on his father's side the Bartók family was a Hungarian lower noble family, originating from Borsod county (Móser 2006, 44; Bartók 1981, 13), though his mother was from a Roman Catholic Serbian family

Serbs

The Serbs are a South Slavic ethnic group of the Balkans and southern Central Europe. Serbs are located mainly in Serbia, Montenegro and Bosnia and Herzegovina, and form a sizable minority in Croatia, the Republic of Macedonia and Slovenia. Likewise, Serbs are an officially recognized minority in...

(Bayley 2001, 16). His mother, Paula (born Paula Voit), had German as a mother tongue, but was ethnically of "mixed Hungarian" origin: Her maiden name Voit is German, probably of Saxon origin from Upper Hungary (Since 1920 in Czechoslovakia, since 1993 in Slovakia), though she spoke Hungarian

Hungarian language

Hungarian is a Uralic language, part of the Ugric group. With some 14 million speakers, it is one of the most widely spoken non-Indo-European languages in Europe....

fluently. Among her closest forefathers there were family names like Polereczky (Magyarized Polish or Slovak) and Fegyveres (Magyar). Béla displayed notable musical talent very early in life: according to his mother, he could distinguish between different dance rhythms that she played on the piano before he learned to speak in complete sentences (Gillies 1990, 6). By the age of four, he was able to play 40 pieces on the piano; his mother began formally teaching him the next year.

Béla was a small and sickly child and suffered from severe eczema until the age of five (Gillies 1990, 5). In 1888, when he was seven, his father (the director of an agricultural school) died suddenly. Béla's mother then took him and his sister, Erzsébet, to live in Nagyszőlős (today Vinogradiv, Ukraine) and then to Pozsony (German: Pressburg, today Bratislava

Bratislava

Bratislava is the capital of Slovakia and, with a population of about 431,000, also the country's largest city. Bratislava is in southwestern Slovakia on both banks of the Danube River. Bordering Austria and Hungary, it is the only national capital that borders two independent countries.Bratislava...

, Slovakia). In Pozsony, Béla gave his first public recital at age eleven to a warm critical reception. Among the pieces he played was his own first composition, written two years previously: a short piece called "The Course of the Danube" (de Toth 1999). Shortly thereafter László Erkel accepted him as a pupil.

Early musical career (1899–1908)

István Thomán

István Thomán was a Hungarian piano virtuoso and music educator. He was appointed by Franz Liszt to teach at the Royal Hungarian Academy of Music in Budapest . István Thomán was a notable piano teacher, with students including Ernő Dohnányi, Georges Cziffra, and Béla Bartók...

, a former student of Franz Liszt

Franz Liszt

Franz Liszt ; ), was a 19th-century Hungarian composer, pianist, conductor, and teacher.Liszt became renowned in Europe during the nineteenth century for his virtuosic skill as a pianist. He was said by his contemporaries to have been the most technically advanced pianist of his age...

, and composition under János Koessler at the Royal Academy of Music in Budapest

Franz Liszt Academy of Music

The Franz Liszt Academy of Music is a concert hall and music conservatory in Budapest, Hungary, founded on November 14, 1875...

. There he met Zoltán Kodály

Zoltán Kodály

Zoltán Kodály was a Hungarian composer, ethnomusicologist, pedagogue, linguist, and philosopher. He is best known internationally as the creator of the Kodály Method.-Life:Born in Kecskemét, Kodály learned to play the violin as a child....

, who influenced him greatly and became his lifelong friend and colleague. In 1903, Bartók wrote his first major orchestral work, Kossuth

Kossuth (Bartók)

Kossuth, Sz. 75a, BB 31, is a symphonic poem by Béla Bartók inspired by the Hungarian politician Lajos Kossuth.-Musical background:The music of Richard Strauss was an early influence on Bartók, who was studying at the Budapest Royal Academy of Music when he encountered the symphonic poems of...

, a symphonic poem

Symphonic poem

A symphonic poem or tone poem is a piece of orchestral music in a single continuous section in which the content of a poem, a story or novel, a painting, a landscape or another source is illustrated or evoked. The term was first applied by Hungarian composer Franz Liszt to his 13 works in this vein...

which honored Lajos Kossuth

Lajos Kossuth

Lajos Kossuth de Udvard et Kossuthfalva was a Hungarian lawyer, journalist, politician and Regent-President of Hungary in 1849. He was widely honored during his lifetime, including in the United Kingdom and the United States, as a freedom fighter and bellwether of democracy in Europe.-Family:Lajos...

, hero of the Hungarian Revolution of 1848

Hungarian Revolution of 1848

The Hungarian Revolution of 1848 was one of many of the European Revolutions of 1848 and closely linked to other revolutions of 1848 in the Habsburg areas...

.

The music of Richard Strauss

Richard Strauss

Richard Georg Strauss was a leading German composer of the late Romantic and early modern eras. He is known for his operas, which include Der Rosenkavalier and Salome; his Lieder, especially his Four Last Songs; and his tone poems and orchestral works, such as Death and Transfiguration, Till...

, whom he met in 1902 at the Budapest

Budapest

Budapest is the capital of Hungary. As the largest city of Hungary, it is the country's principal political, cultural, commercial, industrial, and transportation centre. In 2011, Budapest had 1,733,685 inhabitants, down from its 1989 peak of 2,113,645 due to suburbanization. The Budapest Commuter...

premiere of Also sprach Zarathustra, strongly influenced his early work. When visiting a holiday resort in the summer of 1904, Bartók overheard a young nanny, Lidi Dósa from Kibéd in Transylvania, sing folk songs to the children in her care. This sparked his life-long dedication to folk music.

From 1907 he also began to be influenced by the French composer Claude Debussy

Claude Debussy

Claude-Achille Debussy was a French composer. Along with Maurice Ravel, he was one of the most prominent figures working within the field of impressionist music, though he himself intensely disliked the term when applied to his compositions...

, whose compositions Kodály had brought back from Paris. Bartók's large-scale orchestral works were still in the style of Johannes Brahms

Johannes Brahms

Johannes Brahms was a German composer and pianist, and one of the leading musicians of the Romantic period. Born in Hamburg, Brahms spent much of his professional life in Vienna, Austria, where he was a leader of the musical scene...

and Richard Strauss, but he wrote a number of small piano pieces which showed his growing interest in folk music. The first piece to show clear signs of this new interest is the String Quartet No. 1

String Quartet No. 1 (Bartók)

The String Quartet No. 1 in A minor by Béla Bartók was completed in 1909. The score is dated January 27 of that year.The work is in three movements, played without breaks between each:#Lento...

in A minor (1908), which contains folk-like elements.

In 1907, Bartók began teaching as a piano professor at the Royal Academy. This position freed him from touring Europe as a pianist and enabled him to work in Hungary. Among his notable students were Fritz Reiner

Fritz Reiner

Frederick Martin “Fritz” Reiner was a prominent conductor of opera and symphonic music in the twentieth century.-Biography:...

, Sir Georg Solti, György Sándor

György Sándor

György Sándor was a Hungarian pianist, writer, student and friend of Béla Bartók, and champion of his music.- Early years :...

, Ernő Balogh

Erno Balogh

Ernő Balogh was a Hungarian pianist, composer, editor, and teacher. He was born on April 4, 1897 in Budapest, Hungary and died on June 2, 1989 in Mitchellville, Maryland, USA.-Biography:...

, and Lili Kraus

Lili Kraus

Lili Kraus was a Hungarian-born British pianist.-Biography:Lili Kraus was born in Budapest in 1903. Her father was from Czech Lands, and her mother from an assimilated Jewish Hungarian family....

. After Bartók moved to the United States, he taught Jack Beeson

Jack Beeson

Jack Beeson was an American composer. He was known particularly for his operas, the best known of which are Lizzie Borden, Hello Out There! and The Sweet Bye and Bye.-Biography:...

and Violet Archer

Violet Archer

Violet Archer, CM was a Canadian composer, teacher, pianist, organist, and percussionist. Born Violet Balestreri in Montreal, Quebec, her family changed their name to Archer. She died in Ottawa....

.

In 1908, he and Kodály traveled into the countryside to collect and research old Magyar folk melodies. Their growing interest in folk music coincided with a contemporary social interest in traditional national culture. They made some surprising discoveries. Magyar folk music had previously been categorised as Gypsy music. The classic example is Franz Liszt

Franz Liszt

Franz Liszt ; ), was a 19th-century Hungarian composer, pianist, conductor, and teacher.Liszt became renowned in Europe during the nineteenth century for his virtuosic skill as a pianist. He was said by his contemporaries to have been the most technically advanced pianist of his age...

's famous Hungarian Rhapsodies

Hungarian Rhapsodies

Hungarian Rhapsody redirects here. For the 1979 Hungarian film Hungarian Rhapsody . For the 1928 German film Ungarische Rhapsodie.The Hungarian Rhapsodies, S.244, R106, is a set of 19 piano pieces based on Hungarian folk themes, composed by Franz Liszt during 1846-1853, and later in 1882 and 1885...

for piano, which he based on popular art songs performed by Romani bands of the time. In contrast, Bartók and Kodály discovered that the old Magyar folk melodies were based on pentatonic scales, similar to those in Asian folk traditions, such as those of Central Asia and Siberia

Siberia

Siberia is an extensive region constituting almost all of Northern Asia. Comprising the central and eastern portion of the Russian Federation, it was part of the Soviet Union from its beginning, as its predecessor states, the Tsardom of Russia and the Russian Empire, conquered it during the 16th...

.

Bartók and Kodály quickly set about incorporating elements of such Magyar peasant music into their compositions. They both frequently quoted folk song melodies verbatim and wrote pieces derived entirely from authentic songs. An example is his two volumes entitled For Children for solo piano, containing 80 folk tunes to which he wrote accompaniment. Bartók's style in his art music compositions was a synthesis of folk music, classicism, and modernism. His melodic and harmonic sense was profoundly influenced by the folk music of Hungary, Romania, and other nations. He was especially fond of the asymmetrical dance rhythms and pungent harmonies found in Bulgarian music. Most of his early compositions offer a blend of nationalist and late Romanticism elements.

Personal Life

In 1909, Bartók married Márta Ziegler. Their son, Béla III, was born in 1910. After nearly 15 years together, Bartók divorced Márta in 1923.He then married Ditta Pásztory, a piano student. She had his second son, Péter, born in 1924.

Opera

In 1911, Bartók wrote what was to be his only opera, Bluebeard's CastleBluebeard's Castle

Duke Bluebeard's Castle is a one-act opera by Hungarian composer Béla Bartók. The libretto was written by Béla Balázs, a poet and friend of the composer. It is in Hungarian, based on the French fairy tale "Bluebeard" by Charles Perrault...

, dedicated to Márta. He entered it for a prize by the Hungarian Fine Arts Commission, but they rejected his work as not fit for the stage (Chalmers 1995, 93). In 1917 Bartók revised the score for the 1918 première, and rewrote the ending. Following the 1919 revolution

Hungarian Soviet Republic

The Hungarian Soviet Republic or Soviet Republic of Hungary was a short-lived Communist state established in Hungary in the aftermath of World War I....

, he was pressured by the new Soviet government to remove the name of the librettist Béla Balázs

Béla Balázs

----Béla Balázs , born Herbert Bauer, was a Hungarian-Jewish film critic, aesthete, writer and poet....

from the opera (Chalmers 1995, 123), as he was blacklisted and had left the country for Vienna. Bluebeard's Castle received only one revival, in 1936, before Bartók emigrated. For the remainder of his life, although he was passionately devoted to Hungary, its people and its culture, he never felt much loyalty to the government or its official establishments.

Folk music and composition

After his disappointment over the Fine Arts Commission competition, Bartók wrote little for two or three years, preferring to concentrate on collecting and arranging folk music. He collected first in the Carpathian Basin (the then-Kingdom of Hungary), where he notated HungarianHungarian folk music

Hungarian folk music includes a broad array of styles, including the recruitment dance verbunkos, the csárdás and nóta.During the 20th century, Hungarian composers were influenced by the traditional music of their nation which may be considered as a repeat of the early "nationalist" movement of the...

, Slovakian

Music of Slovakia

The music of Slovakia has been influenced both by the county's native Slovak peoples and the music of neighbouring regions. Whilst there are traces of pre-historic musical instruments, the country has a rich heritage of folk music and mediaeval liturgical music, and from the 18th century onwards,...

, Romanian

Music of Romania

Romania is a European country with a multicultural music environment which includes active ethnic music scenes. Romania also has thriving scenes in the fields of pop music, hip hop, heavy metal and rock and roll...

and Bulgarian

Music of Bulgaria

The music of Bulgaria refers to all forms of music associated with Bulgaria like classical, folk, popular music, etc. Bulgarian music is part of the Balkan tradition, which stretches across Southeastern Europe, and has its own distinctive sound...

folk music. He also collected in Moldavia

Moldavia

Moldavia is a geographic and historical region and former principality in Eastern Europe, corresponding to the territory between the Eastern Carpathians and the Dniester river...

, Wallachia

Wallachia

Wallachia or Walachia is a historical and geographical region of Romania. It is situated north of the Danube and south of the Southern Carpathians...

and in 1913 in Algeria

Algeria

Algeria , officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria , also formally referred to as the Democratic and Popular Republic of Algeria, is a country in the Maghreb region of Northwest Africa with Algiers as its capital.In terms of land area, it is the largest country in Africa and the Arab...

. The outbreak of World War I forced him to stop the expeditions, and he returned to composing, writing the ballet The Wooden Prince

The Wooden Prince

The Wooden Prince Op. 13, Sz. 60, is a one-act pantomime ballet composed by Béla Bartók in 1914-1916 to a scenario by Béla Balázs...

in 1914–16 and the String Quartet No. 2

String Quartet No. 2 (Bartók)

The String Quartet No. 2 by Béla Bartók was written between 1915 and October 1917 in Rákoskeresztúr in Hungary.The work is in three movements:#Moderato#Allegro molto capriccioso#Lento...

in 1915–17, both influenced by Debussy.

Raised as a Roman Catholic, by his early adulthood Bartók had become an atheist. He believed that the existence of God could not be determined and was unnecessary. He later became attracted to Unitarianism

Unitarianism

Unitarianism is a Christian theological movement, named for its understanding of God as one person, in direct contrast to Trinitarianism which defines God as three persons coexisting consubstantially as one in being....

and publicly converted to the Unitarian

Unitarianism

Unitarianism is a Christian theological movement, named for its understanding of God as one person, in direct contrast to Trinitarianism which defines God as three persons coexisting consubstantially as one in being....

faith in 1916. As an adult, his son later became president of the Hungarian Unitarian Church (Hughes 1999–2007).

Bartók wrote another ballet, The Miraculous Mandarin

The Miraculous Mandarin

The Miraculous Mandarin or The Wonderful Mandarin Op. 19, Sz. 73 , is a one act pantomime ballet composed by Béla Bartók between 1918–1924, and based on the story by Melchior Lengyel. Premiered November 27, 1926 in Cologne, Germany, it caused a scandal and was subsequently banned...

influenced by Igor Stravinsky

Igor Stravinsky

Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky ; 6 April 1971) was a Russian, later naturalized French, and then naturalized American composer, pianist, and conductor....

, Arnold Schoenberg

Arnold Schoenberg

Arnold Schoenberg was an Austrian composer, associated with the expressionist movement in German poetry and art, and leader of the Second Viennese School...

, as well as Richard Strauss

Richard Strauss

Richard Georg Strauss was a leading German composer of the late Romantic and early modern eras. He is known for his operas, which include Der Rosenkavalier and Salome; his Lieder, especially his Four Last Songs; and his tone poems and orchestral works, such as Death and Transfiguration, Till...

. He next wrote his two violin sonata

Violin sonata

A violin sonata is a musical composition for violin, which is nearly always accompanied by a piano or other keyboard instrument, or by figured bass in the Baroque period.-A:*Ella Adayevskaya**Sonata Greca for Violin or Clarinet and Piano...

s (written in 1921 and 1922 respectively), which are harmonically and structurally some of his most complex pieces. The Miraculous Mandarin

The Miraculous Mandarin

The Miraculous Mandarin or The Wonderful Mandarin Op. 19, Sz. 73 , is a one act pantomime ballet composed by Béla Bartók between 1918–1924, and based on the story by Melchior Lengyel. Premiered November 27, 1926 in Cologne, Germany, it caused a scandal and was subsequently banned...

, a modern story of prostitution, robbery, and murder, was started in 1918, but not performed until 1926 because of its sexual

Human sexuality

Human sexuality is the awareness of gender differences, and the capacity to have erotic experiences and responses. Human sexuality can also be described as the way someone is sexually attracted to another person whether it is to opposite sexes , to the same sex , to either sexes , or not being...

content.

In 1927–28, Bartók wrote his third

String Quartet No. 3 (Bartók)

The String Quartet No. 3 by Béla Bartók was written in September 1926 in Budapest.The work is in one continuous stretch with no breaks, but is divided in the score into four parts:#Prima parte: Moderato#Seconda parte: Allegro...

and fourth

String Quartet No. 4 (Bartók)

The String Quartet No. 4 by Béla Bartók was written from July to September, 1927 in Budapest.The work is in five movements:#Allegro#Prestissimo, con sordino#Non troppo lento#Allegretto pizzicato#Allegro molto...

string quartet

String quartet

A string quartet is a musical ensemble of four string players – usually two violin players, a violist and a cellist – or a piece written to be performed by such a group...

s, after which his compositions demonstrate his mature style. Notable examples of this period are Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta

Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta

Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta, Sz. 106, BB 114 is one of the best-known compositions by the Hungarian composer Béla Bartók. Commissioned by Paul Sacher to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the Basel Chamber Orchestra, the score is dated September 7, 1936...

(1936) and Divertimento for String Orchestra BB 118

Divertimento for String Orchestra BB 118

Divertimento for String Orchestra Sz.113 BB.118 is a three-movement work composed by Béla Bartók in 1939, scored for full orchestral strings. Paul Sacher, a Swiss conductor, patron, impresario, and the founder of the Basel Chamber Orchestra , commissioned Bartók to compose the Divertimento, which...

(1939). The String Quartet No. 5

String Quartet No. 5 (Bartók)

The String Quartet No. 5 Sz. 102, BB 110 by Béla Bartók was written between August 6 and September 6, 1934.The work is in five movements:#Allegro#Adagio molto#Scherzo: alla bulgarese#Andante#Finale: Allegro vivace...

was composed in 1934, and the sixth

String Quartet No. 6 (Bartók)

The String Quartet No. 6 by Béla Bartók was written from August to November, 1939 in Budapest.The work is in four movements:#Mesto - Vivace#Mesto - Marcia#Mesto - Burletta#Mesto - Molto tranquillo...

and last string quartet in 1939.

In 1936 he travelled to Turkey

Turkey

Turkey , known officially as the Republic of Turkey , is a Eurasian country located in Western Asia and in East Thrace in Southeastern Europe...

to collect and study folk music. He worked in collaboration with Turkish composer Ahmet Adnan Saygun

Ahmet Adnan Saygun

Ahmed Adnan Saygun was a Turkish composer, musicologist and writer on music. Ahmed Adnan Saygun is acknowledged as one of the most important 20th century composers in Turkish music history....

mostly around Adana

Adana

Adana is a city in southern Turkey and a major agricultural and commercial center. The city is situated on the Seyhan River, 30 kilometres inland from the Mediterranean, in south-central Anatolia...

(Özgentürk 2008; Sipos 2000).

World War II and last years in America (1940–45)

In 1940, as the European political situation worsened after the outbreak of World War II, Bartók was increasingly tempted to flee Hungary. He was strongly opposed to the Nazis and Hungary’s siding with Germany. After the Nazis came to power in the early 1930s, Bartók refused to give concerts in Germany and broke with his publisher there. His anti-fascist political views caused him a great deal of trouble with the establishment in Hungary. Having first sent his manuscripts out of the country, Bartók reluctantly emigrated to the U.S. with Ditta Pásztory in July that year. They settled in New York City. After joining them in 1942, his younger son, Péter Bartók, enlisted in the United States NavyUnited States Navy

The United States Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the seven uniformed services of the United States. The U.S. Navy is the largest in the world; its battle fleet tonnage is greater than that of the next 13 largest navies combined. The U.S...

where he served in the Pacific during the remainder of the war. His oldest son, Béla Bartók, Jr., remained in Hungary.

Bartók never became fully at home in the US. He initially found it difficult to compose. Although well known in America as a pianist, ethnomusicologist and teacher, he was not well known as a composer. There was little American interest in his music during his final years. He and his wife Ditta gave concerts. Bartók, who had made some recordings in Hungary also recorded for Columbia Records

Columbia Records

Columbia Records is an American record label, owned by Japan's Sony Music Entertainment, operating under the Columbia Music Group with Aware Records. It was founded in 1888, evolving from an earlier enterprise, the American Graphophone Company — successor to the Volta Graphophone Company...

after he came to the US; many of these recordings (some with Bartók's own spoken introductions) were later issued on LP and CD (Bartók 1994, 1995a, 1995b, 2003 2007, 2008).

Supported by a research fellowship from Columbia University

Columbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York is a private, Ivy League university in Manhattan, New York City. Columbia is the oldest institution of higher learning in the state of New York, the fifth oldest in the United States, and one of the country's nine Colonial Colleges founded before the...

, for several years, Bartók and Ditta worked on a large collection of Serbian

Serbian language

Serbian is a form of Serbo-Croatian, a South Slavic language, spoken by Serbs in Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Croatia and neighbouring countries....

and Croatian

Croatian language

Croatian is the collective name for the standard language and dialects spoken by Croats, principally in Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Serbian province of Vojvodina and other neighbouring countries...

folk songs in Columbia's libraries. They also translated some old Hungarian textbooks into English which were also from Columbia's libraries. Bartók's economic difficulties during his first years in America were mitigated by publication royalties, teaching and performance tours. While his finances were always precarious, he did not live and die in poverty as was the common myth. He had enough supporters to ensure that there was sufficient money and work available for him to live on. Bartók was a proud man and did not easily accept charity. Despite being short on cash at times, he often refused money that his friends offered him out of their own pockets. Although he was not a member of the ASCAP, the society paid for any medical care he needed during his last two years. Bartók accepted this (Chalmers 1995, 196–203).

The first symptoms of his health problems began late in 1940, when his right shoulder began to show signs of stiffening. In 1942, symptoms increased and he started having bouts of fever, but no underlying disease was diagnosed, in spite of medical examinations. Finally, in April 1944, leukemia

Leukemia

Leukemia or leukaemia is a type of cancer of the blood or bone marrow characterized by an abnormal increase of immature white blood cells called "blasts". Leukemia is a broad term covering a spectrum of diseases...

was diagnosed, but by this time, little could be done (Chalmers 1995, 202–207).

As his body slowly failed, Bartók found more creative energy, and he produced a final set of masterpieces, partly thanks to the violinist Joseph Szigeti

Joseph Szigeti

Joseph Szigeti was a Hungarian violinist.Born into a musical family, he spent his early childhood in a small town in Transylvania. He quickly proved himself to be a child prodigy on the violin, and moved to Budapest with his father to study with the renowned pedagogue Jenő Hubay...

and the conductor Fritz Reiner

Fritz Reiner

Frederick Martin “Fritz” Reiner was a prominent conductor of opera and symphonic music in the twentieth century.-Biography:...

(Reiner had been Bartók's friend and champion since his days as Bartók's student at the Royal Academy). Bartók's last work might well have been the String Quartet No. 6

String Quartet No. 6 (Bartók)

The String Quartet No. 6 by Béla Bartók was written from August to November, 1939 in Budapest.The work is in four movements:#Mesto - Vivace#Mesto - Marcia#Mesto - Burletta#Mesto - Molto tranquillo...

but for Serge Koussevitsky's commission

Commission (art)

In art, a commission is the hiring and payment for the creation of a piece, often on behalf of another.In classical music, ensembles often commission pieces from composers, where the ensemble secures the composer's payment from private or public organizations or donors.- Commissions for public art...

for the Concerto for Orchestra

Concerto for Orchestra (Bartók)

Concerto for Orchestra, Sz. 116, BB 123, is a five-movement musical work for orchestra composed by Béla Bartók in 1943. It is one of his best-known, most popular and most accessible works. The score is inscribed "15 August – 8 October 1943", and it premiered on December 1, 1944 in Boston Symphony...

. Koussevitsky's Boston Symphony Orchestra

Boston Symphony Orchestra

The Boston Symphony Orchestra is an orchestra based in Boston, Massachusetts. It is one of the five American orchestras commonly referred to as the "Big Five". Founded in 1881, the BSO plays most of its concerts at Boston's Symphony Hall and in the summer performs at the Tanglewood Music Center...

premièred the work in December 1944 to highly positive reviews. Concerto for Orchestra quickly became Bartók's most popular work, although he did not live to see its full impact. In 1944, he was also commissioned by Yehudi Menuhin

Yehudi Menuhin

Yehudi Menuhin, Baron Menuhin, OM, KBE was a Russian Jewish American violinist and conductor who spent most of his performing career in the United Kingdom. He was born to Russian Jewish parents in the United States, but became a citizen of Switzerland in 1970, and of the United Kingdom in 1985...

to write a Sonata for Solo Violin

Sonata for Solo Violin (Bartók)

The Sonata for Solo Violin Sz. 117, BB 124, is a sonata for unaccompanied violin composed by Béla Bartók. It was premiered by Yehudi Menuhin, to whom it was dedicated, in New York on 26 November, 1944.-Composition:...

. In 1945, Bartók composed his Piano Concerto No. 3

Piano Concerto No. 3 (Bartók)

Béla Bartók's Piano Concerto No. 3 in E major, Sz. 119, BB 127 is a musical composition for piano and orchestra. The piece was composed in 1945 by Hungarian composer Béla Bartók during the final months of his life. It consists of three movements.-Context:...

, a graceful and almost neo-classical work. He began work on his Viola Concerto

Viola Concerto (Bartók)

Béla Bartók's Viola Concerto, Sz. 120, BB 128 was written in July – August 1945, in Saranac Lake, New York, while he was suffering from the terminal stages of leukemia. It was commissioned by William Primrose. Along with the Piano Concerto No. 3, it is his last work, and he left it incomplete at...

, but had not completed the scoring at his death.

Leukemia

Leukemia or leukaemia is a type of cancer of the blood or bone marrow characterized by an abnormal increase of immature white blood cells called "blasts". Leukemia is a broad term covering a spectrum of diseases...

(specifically, of secondary polycythemia

Polycythemia

Polycythemia is a disease state in which the proportion of blood volume that is occupied by red blood cells increases...

) on September 26, 1945. His funeral was attended by only ten people. Among them were his wife Ditta, their son Péter, and his pianist friend György Sándor

György Sándor

György Sándor was a Hungarian pianist, writer, student and friend of Béla Bartók, and champion of his music.- Early years :...

(anon. 2006).

Bartok's body was initially interred in Ferncliff Cemetery

Ferncliff Cemetery

Ferncliff Cemetery and Mausoleum is located on Secor Road in the hamlet of Hartsdale, town of Greenburgh, Westchester County, New York, about 25 miles north of Midtown Manhattan. It was founded in 1902, and is non-sectarian...

in Hartsdale, New York. During the final year of communist Hungary in the late 1980s, the Hungarian government, along with his two sons, Béla III and Péter, requested that his remains be exhumed and transferred back to Budapest

Budapest

Budapest is the capital of Hungary. As the largest city of Hungary, it is the country's principal political, cultural, commercial, industrial, and transportation centre. In 2011, Budapest had 1,733,685 inhabitants, down from its 1989 peak of 2,113,645 due to suburbanization. The Budapest Commuter...

for burial, where Hungary arranged a state funeral

State funeral

A state funeral is a public funeral ceremony, observing the strict rules of protocol, held to honor heads of state or other important people of national significance. State funerals usually include much pomp and ceremony as well as religious overtones and distinctive elements of military tradition...

for him on July 7, 1988. He was reinterred at Budapest's Farkasréti Cemetery

Farkasréti Cemetery

Farkasréti Cemetery or Farkasrét Cemetery is one of the most famous cemeteries in Budapest. It was opened in 1894 and is noted for its spectacular sight towards the city ....

(Chalmers 1995, 214).

The Third Piano Concerto was nearly finished at his death. Bartok had completed only the viola part and sketches of the orchestra part for the Viola Concerto. Both works were later completed by his pupil, Tibor Serly

Tibor Serly

Tibor Serly was a Hungarian violist, violinist and composer.He was one of the students of Zoltán Kodály. He greatly admired and became a young apprentice of Béla Bartók. His association with Bartók was for him both a blessing and a curse...

. György Sándor was the soloist in the first performance of the Third Piano Concerto on February 8, 1946. The Viola Concerto was revised and polished in the 1990s by Bartók's son, Peter; this version may be closer to what Bartók intended (Chalmers 1995, 210).

Legacy and honors

- A statue of Béla Bartók stands in BrusselsBrusselsBrussels , officially the Brussels Region or Brussels-Capital Region , is the capital of Belgium and the de facto capital of the European Union...

, Belgium near the central train station in a public square, Spanjeplein-Place d'Espagne. - A statue stands outside Malvern Court, south of South KensingtonSouth KensingtonSouth Kensington is a district in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea in London. It is a built-up area located 2.4 miles west south-west of Charing Cross....

Underground StationLondon UndergroundThe London Underground is a rapid transit system serving a large part of Greater London and some parts of Buckinghamshire, Hertfordshire and Essex in England...

, and just north of Sydney Place, where he stayed when performing in London. - A statue of him was installed in front of one of the houses which Bartók owned in the hills above Budapest. It is now operated as a house museum.

- A bust and plaque located at his last residence, in New York City at 309 W. 57th Street, inscribed: "The Great Hungarian Composer / Béla Bartók / (1881–1945) / Made His Home In This House / During the Last Year of His Life".

Compositions

Bartók's music reflects two trends that dramatically changed the sound of music in the 20th century: the breakdown of the diatonic system of harmony that had served composers for the previous two hundred years (Griffiths 1978, 7); and the revival of nationalism as a source for musical inspiration, a trend that began with Mikhail GlinkaMikhail Glinka

Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka , was the first Russian composer to gain wide recognition within his own country, and is often regarded as the father of Russian classical music...

and Antonín Dvořák

Antonín Dvorák

Antonín Leopold Dvořák was a Czech composer of late Romantic music, who employed the idioms of the folk music of Moravia and his native Bohemia. Dvořák’s own style is sometimes called "romantic-classicist synthesis". His works include symphonic, choral and chamber music, concerti, operas and many...

in the last half of the 19th century (Einstein 1947, 332). In his search for new forms of tonality, Bartók turned to Hungarian folk music, as well as to other folk music of the Carpathian Basin and even of Algeria and Turkey; in so doing he became influential in that stream of modernism which exploited indigenous music and techniques (Botstein [n.d.], §6).

One characteristic style of music is his Night music

Night music (Bartók)

Night Music is a musical style of the Hungarian composer Béla Bartók which he used mostly in slow movements of multi-movement ensemble or orchestra compositions in his mature period...

, which he used mostly in slow movements of multi-movement ensemble or orchestral compositions in his mature period. It is characterised by "eerie dissonances providing a backdrop to sounds of nature and lonely melodies" (Schneider 2006, 84). An example is the third movement Adagio of his Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta

Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta

Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta, Sz. 106, BB 114 is one of the best-known compositions by the Hungarian composer Béla Bartók. Commissioned by Paul Sacher to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the Basel Chamber Orchestra, the score is dated September 7, 1936...

.

His music can be grouped roughly in accordance with the different periods in his life.

Youth: Late-Romanticism (1890–1902)

The works of his youth are of a late-Romantic style. Between 1890 and 1894 (nine to 13 years of age) he wrote 31 pieces with corresponding opus numbers. He started numbering his works anew with ‘opus 1’ in 1894 with his first large scale work, a piano sonata. Up to 1902, Bartók wrote in total 74 works which can be considered in Romantic style. Most of these early compositions are either scored for piano solo or include a piano. Additionally, there is some chamber music for strings. Compared to his later achievements, these works are of less importance.New influences (1903–11)

Under the influence of Richard StraussRichard Strauss

Richard Georg Strauss was a leading German composer of the late Romantic and early modern eras. He is known for his operas, which include Der Rosenkavalier and Salome; his Lieder, especially his Four Last Songs; and his tone poems and orchestral works, such as Death and Transfiguration, Till...

(among other works Also sprach Zarathustra

Also sprach Zarathustra (Richard Strauss)

Also sprach Zarathustra, Op. 30 is a tone poem by Richard Strauss, composed in 1896 and inspired by Friedrich Nietzsche's philosophical treatise of the same name. The composer conducted its first performance on 27 November 1896 in Frankfurt...

) (Stevens 1993, 15–17), Bartók composed in 1903 Kossuth

Kossuth (Bartók)

Kossuth, Sz. 75a, BB 31, is a symphonic poem by Béla Bartók inspired by the Hungarian politician Lajos Kossuth.-Musical background:The music of Richard Strauss was an early influence on Bartók, who was studying at the Budapest Royal Academy of Music when he encountered the symphonic poems of...

, a symphonic poem in ten tableaux. In 1904 followed his Rhapsody for piano and orchestra which he numbered opus 1 again, marking it himself as the start of a new era in his music. An even more important occurrence of this year was his overhearing the eighteen-year-old nanny Lidi Dósa from Transylvania

Transylvania

Transylvania is a historical region in the central part of Romania. Bounded on the east and south by the Carpathian mountain range, historical Transylvania extended in the west to the Apuseni Mountains; however, the term sometimes encompasses not only Transylvania proper, but also the historical...

sing folk songs, sparking Bartók’s lifelong dedication to folk music (Stevens 1993, 22). When criticised for not composing his own melodies Bartók pointed out that Molière

Molière

Jean-Baptiste Poquelin, known by his stage name Molière, was a French playwright and actor who is considered to be one of the greatest masters of comedy in Western literature...

and Shakespeare mostly based their plays on well-known stories too. Regarding the incorporation of folk music into art music he said:

The question is, what are the ways in which peasant music is taken over and becomes transmuted into modern music? We may, for instance, take over a peasant melody unchanged or only slightly varied, write an accompaniment to it and possibly some opening and concluding phrases. This kind of work would show a certain analogy with Bach’s treatment of chorales. [...] Another method [...] is the following: the composer does not make use of a real peasant melody but invents his own imitation of such melodies. There is no true difference between this method and the one described above. [...] There is yet a third way [...] Neither peasant melodies nor imitations of peasant melodies can be found in his music, but it is pervaded by the atmosphere of peasant music. In this case we may say, he has completely absorbed the idiom of peasant music which has become his musical mother tongue. (Bartók 1931/1976, 341–44.)

Bartók became first acquainted with Debussy’s music in 1907 and regarded his music highly. In an interview in 1939 Bartók said

Debussy's influence is present in the Fourteen Bagatelles (1908). These made Ferruccio Busoni

Debussy's great service to music was to reawaken among all musicians an awareness of harmony and its possibilities. In that, he was just as important as Beethoven, who revealed to us the possibilities of progressive form, or as Bach, who showed us the transcendent significance of counterpoint. Now, what I am always asking myself is this: is it possible to make a synthesis of these three great masters, a living synthesis that will be valid for our time? (Moreux 1953, 92)

Ferruccio Busoni

Ferruccio Busoni was an Italian composer, pianist, editor, writer, piano and composition teacher, and conductor.-Biography:...

exclaim ‘At last something truly new!’ (Bartók, 1948, 2:83). Until 1911, Bartók composed widely differing works which ranged from adherence to romantic-style, to folk song arrangements and to his modernist opera Bluebeard’s Castle. The negative reception of his work led him to focus on folk music research after 1911 and abandon composition with the exception of folk music arrangements (Gillies 1993, 404; Stevens 1964, 47–49).

New inspiration and experimentation (1916–21)

His pessimistic attitude towards composing was lifted by the stormy and inspiring contact with Klára Gombossy in the summer of 1915 (Gillies 1993, 405). This interesting episode in Bartók's life remained hidden until it was researched by Denijs Dille between 1979 and 1989 (Dille 1990, 257–77). Bartók started composing again, including the Suite for piano opus 14 (1916), and The Miraculous MandarinThe Miraculous Mandarin

The Miraculous Mandarin or The Wonderful Mandarin Op. 19, Sz. 73 , is a one act pantomime ballet composed by Béla Bartók between 1918–1924, and based on the story by Melchior Lengyel. Premiered November 27, 1926 in Cologne, Germany, it caused a scandal and was subsequently banned...

(1918) and he completed The Wooden Prince (1917).

Bartók felt the result of World War I as a personal tragedy (Stevens 1993, 3). Many regions he loved were severed from Hungary

Hungary

Hungary , officially the Republic of Hungary , is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is situated in the Carpathian Basin and is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine and Romania to the east, Serbia and Croatia to the south, Slovenia to the southwest and Austria to the west. The...

: Transylvania

Transylvania

Transylvania is a historical region in the central part of Romania. Bounded on the east and south by the Carpathian mountain range, historical Transylvania extended in the west to the Apuseni Mountains; however, the term sometimes encompasses not only Transylvania proper, but also the historical...

, the Banat

Banat

The Banat is a geographical and historical region in Central Europe currently divided between three countries: the eastern part lies in western Romania , the western part in northeastern Serbia , and a small...

where he was born, and Pozsony where his mother lived. Additionally, the political relations between Hungary and the other successor states to the Austro-Hungarian empire prohibited his folk music research outside of Hungary (Somfai, 1996, 18). Thrown largely onto himself, he experimented with extreme compositional practices, the peak being his Sonata for Violin and Piano No. 1 (Op. 21) and No. 2. Bartók also wrote the noteworthy Eight Improvisations on Hungarian Peasant Songs in 1920, and the sunny Dance Suite in 1923, the year of his second marriage.

"Synthesis of East and West" (1926–45)

In 1926, Bartók needed a significant piece for piano and orchestra with which he could tour in Europe and America. In the preparation for writing his First Piano ConcertoPiano Concerto No. 1 (Bartók)

The Piano Concerto No. 1 , Sz. 83, BB 91 of Béla Bartók was composed in 1926. It is about 23 to 24 minutes long.-Background:For almost three years, Bartók had composed little. He broke that silence with several piano works, one of which was the piano concerto...

, he wrote his Sonata, Out of Doors, and Nine Little Pieces, all for solo piano (Gillies 1993, 173). He increasingly found his own voice in his maturity. The style of his last period—named "Synthesis of East and West" (Gillies 1993, 189)—is hard to define let alone to put under one term. In his mature period, Bartók wrote relatively few works but most of them are large-scale compositions for large settings. Only his voice works have programmatic titles and his late works often adhere to classical forms.

Among his masterworks are all the six string quartets (1908, 1917, 1927, 1928, 1934, and 1939), the Cantata Profana

Cantata Profana

Cantata Profana Sz. 94, is a choral work for tenor, baritone, choir and orchestra by the Hungarian composer Béla Bartók...

(1930, Bartók declared that this was the work he felt and professed to be his most personal "credo", Szabolcsi 1974, 186), the Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta

Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta

Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta, Sz. 106, BB 114 is one of the best-known compositions by the Hungarian composer Béla Bartók. Commissioned by Paul Sacher to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the Basel Chamber Orchestra, the score is dated September 7, 1936...

(1936), the Concerto for Orchestra

Concerto for Orchestra (Bartók)

Concerto for Orchestra, Sz. 116, BB 123, is a five-movement musical work for orchestra composed by Béla Bartók in 1943. It is one of his best-known, most popular and most accessible works. The score is inscribed "15 August – 8 October 1943", and it premiered on December 1, 1944 in Boston Symphony...

(1943) and the Third Piano Concerto

Piano Concerto No. 3 (Bartók)

Béla Bartók's Piano Concerto No. 3 in E major, Sz. 119, BB 127 is a musical composition for piano and orchestra. The piece was composed in 1945 by Hungarian composer Béla Bartók during the final months of his life. It consists of three movements.-Context:...

(1945).

Bartók also made a lasting contribution to the literature for younger students: for his son Péter's music lessons, he composed Mikrokosmos, a six-volume collection of graded piano pieces.

Analytic approaches

Paul WilsonPaul Wilson (music theorist)

Paul Wilson is a music theorist and Professor of Music Theory and Composition at the University of Miami Frost School of Music, in the United States. He holds a B.A. from Harvard University, a M.A. from the University of Hawaii, and M.Phil. and Ph.D. degrees from Yale University, where he studied...

lists as the most prominent characteristics of Bartók's music from late 1920s onwards the influence of the Carpathian basin and European art music, and his changing attitude toward (and use of) tonality, but without the use of the traditional harmonic functions associated with major and minor scales (Wilson 1992, 2–4).

Although Bartók claimed in his writings that his music was always tonal, it rarely uses the chords or scales of tonality, and so the descriptive resources of tonal theory are of limited use. George Perle

George Perle

George Perle was a composer and music theorist. He was born in Bayonne, New Jersey. Perle was an alumnus of DePaul University...

and Elliott Antokoletz focus on alternative methods of signaling tonal centers, via axes of inversional symmetry. Others view Bartok's axes of symmetry in terms of atonal analytic protocols. Richard Cohn

Richard Cohn

Richard Cohn is a music theorist and Battell Professor of Music Theory at Yale. Early in his career, he specialized in the music of Béla Bartók, but more recently has written about Neo-Riemannian theory as well as metric dissonance.-External links:*...

argues that inversional symmetry is often a byproduct of another atonal procedure, the formation of chords from transpositionally related dyads. Atonal pitch-class theory also furnishes the resources for exploring polymodal chromaticism

Polymodal chromaticism

In music, polymodal chromaticism is the use of any and all musical modes sharing the same final simultaneously or in succession and thus creating a texture involving all twelve notes of the chromatic scale...

, projected set

Projected set

In music a projected set is a technique where a collection of pitches or pitch classes is extended in a texture through the emphasized simultaneous statement of the a set followed or preceded by a successive emphasized statement of each of its members...

s, privileged pattern

Privileged pattern

In music a privileged pattern is a motive, figure, or chord which is repeated and transposed so that the transpositions form a recognizable pattern. The pattern of transposition may be either by a repeated interval, an interval cycle, or a stepwise line of whole tones and semitones...

s, and large set types used as source sets such as the equal tempered twelve tone aggregate, octatonic scale

Octatonic scale

An octatonic scale is any eight-note musical scale. Among the most famous of these is a scale in which the notes ascend in alternating intervals of a whole step and a half step, creating a symmetric scale...

(and alpha chord), the diatonic and heptatonia seconda seven-note scales, and less often the whole tone scale and the primary pentatonic collection (Wilson 1992, 24–29).

He rarely used the simple aggregate actively to shape musical structure, though there are notable examples such as the second theme from the first movement of his Second Violin Concerto, commenting that he "wanted to show Schoenberg

Arnold Schoenberg

Arnold Schoenberg was an Austrian composer, associated with the expressionist movement in German poetry and art, and leader of the Second Viennese School...

that one can use all twelve tones and still remain tonal" (Gillies 1990, 185). More thoroughly, in the first eight measures of the last movement of his Second Quartet, all notes gradually gather with the twelfth (G♭) sounding for the first time on the last beat of measure 8, marking the end of the first section. The aggregate is partitioned in the opening of the Third String Quartet with C♯–D–D♯–E in the accompaniment (strings) while the remaining pitch classes are used in the melody (violin 1) and more often as 7–35 (diatonic or "white-key" collection) and 5–35 (pentatonic or "black-key" collection) such as in no. 6 of the Eight Improvisations. There, the primary theme is on the black keys in the left hand, while the right accompanies with triads from the white keys. In measures 50–51 in the third movement of the Fourth Quartet, the first violin and 'cello play black-key chords, while the second violin and viola play stepwise diatonic lines (Wilson 1992, 25). On the other hand, from as early as the Suite for piano, op. 14 (1914), he occasionally employed a form of serialism

Serialism

In music, serialism is a method or technique of composition that uses a series of values to manipulate different musical elements. Serialism began primarily with Arnold Schoenberg's twelve-tone technique, though his contemporaries were also working to establish serialism as one example of...

based on compound interval cycles, some of which are maximally distributed, multi-aggregate cycles (Martins 2004, Gollin 2007).

Erno Lendvai

Ernő Lendvai was one of the first theorists to write on the appearance of the golden section and Fibonacci series and how these are implemented in Bartók's music...

(1971) analyses Bartók's works as being based on two opposing tonal systems, that of the acoustic scale

Acoustic scale

In music, the acoustic scale, overtone scale, Lydian dominant scale, or Lydian 7 scale, is a seven-note synthetic scale which, starting on C, contains the notes: C, D, E, F, G, A and B. This differs from the major scale in having a raised fourth and lowered seventh scale degree. It is the fourth...

and the axis system

Axis system

In music, the axis system is a system of analysis originating in the work of Ernő Lendvaï, which he developed in his analysis of the music of Béla Bartók....

, as well as using the golden section as a structural principle.

Milton Babbitt

Milton Babbitt

Milton Byron Babbitt was an American composer, music theorist, and teacher. He is particularly noted for his serial and electronic music.-Biography:...

, in his 1949 critique of Bartók's string quartets, criticized Bartók for using tonality and non tonal methods unique to each piece. Babbitt noted that "Bartók's solution was a specific one, it cannot be duplicated" (Babbitt 1949, 385). Bartók's use of "two organizational principles"—tonality for large scale relationships and the piece-specific method for moment to moment thematic elements—was a problem for Babbitt, who worried that the "highly attenuated tonality" requires extreme non-harmonic methods to create a feeling of closure (Babbitt 1949, 377–78).

Catalogues and opus numbers

The cataloguing of Bartók's works is somewhat complex. Bartók assigned opus numbers to his works three times, the last of these series ending with the Sonata for Violin and Piano No. 1, Op. 21 in 1921. He ended this practice because of the difficulty of distinguishing between original works and ethnographic arrangements, and between major and minor works. Since his death, three attempts—two full and one partial—have been made at cataloguing. The first, and still most widely used, is András SzőllősyAndrás Szőllősy

András Szőllősy was the creator of the Szőllősy index , a frequently used index for the works of Hungarian composer Béla Bartók, was born at Szászváros in Transylvania on February 27, 1921. He studied composition under Zoltán Kodály at the Franz Liszt Academy of Music where he was a professor of...

's chronological Sz. numbers, from 1 to 121. Denijs Dille subsequently reorganised the juvenilia (Sz. 1–25) thematically, as DD numbers 1 to 77. The most recent catalogue is that of László Somfai

László Somfai

László Somfai is a Hungarian musicologist.He was born in 1934 in Jászladány. He first studied History of Music, graduating in 1959 with a dissertation on the classical string quartet idiom of Joseph Haydn. He went on to earn a PhD in musicology....

; this is a chronological index with works identified by BB numbers 1 to 129, incorporating corrections based on the Béla Bartók Thematic Catalogue..

Discography

- Bartók, Béla. 1994. Bartók at the Piano. Hungaroton 12326. 6-CD set.

- Bartók, Béla. 1995a. Bartok Plays Bartok – Bartok At The Piano 1929–41. Pearl 9166. CD recording.

- Bartók, Béla. 1995b. Bartók Recordings From Private Collections. Hungaroton 12334. CD recording.

- Bartók, Béla. 2003. Bartók Plays Bartók. Pearl 179. CD recording.

- Bartók, Béla. 2007. Bartók: Contrasts, Mikrokosmos. Membran/Documents 223546. CD recording.

- Bartók, Béla. 2008. Bartok Plays Bartok. Urania 340. CD recording.

Media

Further reading

- Antokoletz, Elliott (1984). The Music of Béla Bartók: A Study of Tonality and Progression in Twentieth-Century Music. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0520046048

- Kárpáti, János (1975). Bartók's String Quartets. Translated by Fred MacNicol. Budapest: Corvina Press.

- Somfai, László. 1981. Tizennyolc Bartók-tanulmány [Eighteen Bartók Studies]. Budapest: Zeneműkiadó. ISBN 9633303702

- Somfai, Lászlo. 1996. Béla Bartók: Composition, Concepts, and Autograph Sources. Ernest Bloch Lectures. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0520084853

External links

- Béla Bartók biography and works on the UE website (publisher)

- The Lied and Art Song Texts Page Original texts of the songs of Bartok with translations in various languages.

- Bartók Béla Memorial House, Budapest

- Bartók and his relationship with Unitarianism

- Gallery of Bartók portraits

- Don Gabor and Laszlo Halasz recorded Béla Bartók at his home in New York

in Sydney Place, London

Recordings

- Kunst der Fuge: Béla Bartók—MIDI files

Sheet music