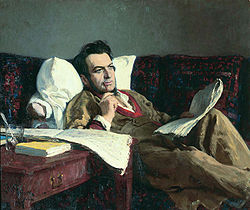

Mikhail Glinka

Encyclopedia

Russians

The Russian people are an East Slavic ethnic group native to Russia, speaking the Russian language and primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries....

composer to gain wide recognition within his own country, and is often regarded as the father of Russian classical music

Classical music

Classical music is the art music produced in, or rooted in, the traditions of Western liturgical and secular music, encompassing a broad period from roughly the 11th century to present times...

. Glinka's compositions were an important influence on future Russian composers, notably the members of The Five

The Five

The Five, also known as The Mighty Handful or The Mighty Coterie , refers to a circle of composers who met in Saint Petersburg, Russia, in the years 1856–1870: Mily Balakirev , César Cui, Modest Mussorgsky, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and Alexander Borodin...

, who took Glinka's lead and produced a distinctive Russian style of music.

Early life

Mikhail Glinka was born in the village of Novospasskoye, not far from the Desna RiverDesna River

Desna is a river in Russia and Ukraine, left tributary of the Dnieper. The word means "right hand" in the Old East Slavic language. Its length is , and its drainage basin covers ....

in the Smolensk

Smolensk Oblast

Smolensk Oblast is a federal subject of Russia . Its area is . Population: -Geography:The administrative center of Smolensk Oblast is the city of Smolensk. Other ancient towns include Vyazma and Dorogobuzh....

Guberniya

Guberniya

A guberniya was a major administrative subdivision of the Russian Empire usually translated as government, governorate, or province. Such administrative division was preserved for sometime upon the collapse of the empire in 1917. A guberniya was ruled by a governor , a word borrowed from Latin ,...

of the Russian Empire

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

. His father was a wealthy retired army captain, as the family had a strong tradition of loyalty and service to the Tsar

Tsar

Tsar is a title used to designate certain European Slavic monarchs or supreme rulers. As a system of government in the Tsardom of Russia and Russian Empire, it is known as Tsarist autocracy, or Tsarism...

, while several members of his extended family had also developed a lively interest in culture. As a small child, Mikhail was reared by his over-protective and pampering grandmother who fed him sweets, wrapped him in furs, and confined him to her room, which was always to be kept at 25 °C (77 °F); as such, he developed a sickly disposition, later in his life retaining the services of numerous physicians, and often falling victim to a number of quacks

Quackery

Quackery is a derogatory term used to describe the promotion of unproven or fraudulent medical practices. Random House Dictionary describes a "quack" as a "fraudulent or ignorant pretender to medical skill" or "a person who pretends, professionally or publicly, to have skill, knowledge, or...

. The only music he heard in his youthful confinement was the sounds of the village church bells and the folk songs of passing peasant choirs. The church bells were tuned to a dissonant chord and so his ears became used to strident harmony. While his nurse would sometimes sing folksongs, the peasant choirs who sang using the podgolosnaya technique (an improvised style — literally under the voice - which uses improvised dissonant harmonies below the melody) influenced the way he later felt free to emancipate himself from the smooth progressions of Western harmony

Classical music

Classical music is the art music produced in, or rooted in, the traditions of Western liturgical and secular music, encompassing a broad period from roughly the 11th century to present times...

. After his grandmother’s death, Glinka was moved to his maternal uncle’s estate some 10 km away, and was able to hear his uncle’s orchestra, whose repertoire included pieces by Haydn

Joseph Haydn

Franz Joseph Haydn , known as Joseph Haydn , was an Austrian composer, one of the most prolific and prominent composers of the Classical period. He is often called the "Father of the Symphony" and "Father of the String Quartet" because of his important contributions to these forms...

, Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart , baptismal name Johannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart , was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical era. He composed over 600 works, many acknowledged as pinnacles of symphonic, concertante, chamber, piano, operatic, and choral music...

and Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven was a German composer and pianist. A crucial figure in the transition between the Classical and Romantic eras in Western art music, he remains one of the most famous and influential composers of all time.Born in Bonn, then the capital of the Electorate of Cologne and part of...

. He was about ten when he heard them play a clarinet quintet

Clarinet quintet

A clarinet quintet is a chamber musical ensemble made up of one clarinet, plus the standard string quartet of two violins, one viola, and one cello. The term is also used to refer to a piece written for this ensemble....

by the Finnish composer Bernhard Henrik Crusell

Bernhard Henrik Crusell

Bernhard Henrik Crusell was a Swedish-Finnish clarinetist, composer and translator, "the most significant and internationally best-known Finnish-born classical composer and indeed, — the outstanding Finnish composer before Sibelius".-Early life and training:Crusell was born in Uusikaupunki ,...

. It had a profound effect upon him. "Music is my soul," he was to write many years later, recalling this experience. While his governess taught him Russian

Russian language

Russian is a Slavic language used primarily in Russia, Belarus, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. It is an unofficial but widely spoken language in Ukraine, Moldova, Latvia, Turkmenistan and Estonia and, to a lesser extent, the other countries that were once constituent republics...

, German

German language

German is a West Germanic language, related to and classified alongside English and Dutch. With an estimated 90 – 98 million native speakers, German is one of the world's major languages and is the most widely-spoken first language in the European Union....

, French

French language

French is a Romance language spoken as a first language in France, the Romandy region in Switzerland, Wallonia and Brussels in Belgium, Monaco, the regions of Quebec and Acadia in Canada, and by various communities elsewhere. Second-language speakers of French are distributed throughout many parts...

, and geography

Geography

Geography is the science that studies the lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena of Earth. A literal translation would be "to describe or write about the Earth". The first person to use the word "geography" was Eratosthenes...

, he also received instruction on the piano

Piano

The piano is a musical instrument played by means of a keyboard. It is one of the most popular instruments in the world. Widely used in classical and jazz music for solo performances, ensemble use, chamber music and accompaniment, the piano is also very popular as an aid to composing and rehearsal...

and the violin

Violin

The violin is a string instrument, usually with four strings tuned in perfect fifths. It is the smallest, highest-pitched member of the violin family of string instruments, which includes the viola and cello....

.

At the age of 13 Glinka was sent to the capital, Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg is a city and a federal subject of Russia located on the Neva River at the head of the Gulf of Finland on the Baltic Sea...

, to study at a school for children of the nobility. Here he was taught Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

, English

English language

English is a West Germanic language that arose in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of England and spread into what was to become south-east Scotland under the influence of the Anglian medieval kingdom of Northumbria...

, and Persian

Persian language

Persian is an Iranian language within the Indo-Iranian branch of the Indo-European languages. It is primarily spoken in Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan and countries which historically came under Persian influence...

, studied mathematics

Mathematics

Mathematics is the study of quantity, space, structure, and change. Mathematicians seek out patterns and formulate new conjectures. Mathematicians resolve the truth or falsity of conjectures by mathematical proofs, which are arguments sufficient to convince other mathematicians of their validity...

and zoology

Zoology

Zoology |zoölogy]]), is the branch of biology that relates to the animal kingdom, including the structure, embryology, evolution, classification, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinct...

, and was able to considerably widen his musical experience. He had three piano lessons from John Field

John Field (composer)

John Field was an Irish pianist, composer, and teacher. He was born in Dublin into a musical family, and received his early education there. The Fields soon moved to London, where Field studied under Muzio Clementi...

, the Irish

Ireland

Ireland is an island to the northwest of continental Europe. It is the third-largest island in Europe and the twentieth-largest island on Earth...

composer of nocturne

Nocturne

A nocturne is usually a musical composition that is inspired by, or evocative of, the night...

s, who spent some time in Saint Petersburg. He then continued his piano lessons with Charles Meyer

Charles Meyer

Charles Meyer , also known as Carl Mayer, was a Russian pianist and composer active in the early 19th century. He was a piano teacher of Mikhail Glinka, a well-known Russian composer....

, and began composing.

When he left school his father wanted him to join the Foreign Office, and he was appointed assistant secretary of the Department of Public Highways. The work was light, which allowed Mikhail to settle into the life of a musical dilettante

Amateur

An amateur is generally considered a person attached to a particular pursuit, study, or science, without pay and often without formal training....

, frequenting the drawing room

Drawing room

A drawing room is a room in a house where visitors may be entertained. The name is derived from the sixteenth-century terms "withdrawing room" and "withdrawing chamber", which remained in use through the seventeenth century, and made its first written appearance in 1642...

s and social gatherings of the city. He was already composing a large amount of music, such as melancholy romances which amused the rich amateurs. His songs are among the most interesting part of his output from this period.

In 1830, at the recommendation of a physician, Glinka decided to travel to Italy

Italy

Italy , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

with the tenor Nikolay Ivanov. The route was leisurely, ambling uneventfully through Germany

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

and Switzerland

Switzerland

Switzerland name of one of the Swiss cantons. ; ; ; or ), in its full name the Swiss Confederation , is a federal republic consisting of 26 cantons, with Bern as the seat of the federal authorities. The country is situated in Western Europe,Or Central Europe depending on the definition....

, before they settled in Milan

Milan

Milan is the second-largest city in Italy and the capital city of the region of Lombardy and of the province of Milan. The city proper has a population of about 1.3 million, while its urban area, roughly coinciding with its administrative province and the bordering Province of Monza and Brianza ,...

. There, Glinka took lessons at the conservatory

Milan Conservatory

The Milan Conservatory is a college of music which was established by a royal decree of 1807 in Milan, capital of the Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy. It opened the following year with premises in the cloisters of the Baroque church of Santa Maria della Passione. There were initially 18 boarders,...

with Francesco Basili

Francesco Basili

Francesco Basili was an Italian composer and conductor. He was born in Loreto and died in Rome.-References:...

, although he struggled with counterpoint

Counterpoint

In music, counterpoint is the relationship between two or more voices that are independent in contour and rhythm and are harmonically interdependent . It has been most commonly identified in classical music, developing strongly during the Renaissance and in much of the common practice period,...

, which he found irksome. Although he spent his three years in Italy listening to singers of the day, romancing women with his music, and meeting many famous people including Mendelssohn

Felix Mendelssohn

Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Barthóldy , use the form 'Mendelssohn' and not 'Mendelssohn Bartholdy'. The Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians gives ' Felix Mendelssohn' as the entry, with 'Mendelssohn' used in the body text...

and Berlioz

Hector Berlioz

Hector Berlioz was a French Romantic composer, best known for his compositions Symphonie fantastique and Grande messe des morts . Berlioz made significant contributions to the modern orchestra with his Treatise on Instrumentation. He specified huge orchestral forces for some of his works; as a...

, he became disenchanted with Italy. He realized that his mission in life was to return to Russia

Russia

Russia or , officially known as both Russia and the Russian Federation , is a country in northern Eurasia. It is a federal semi-presidential republic, comprising 83 federal subjects...

, write in a Russian manner, and do for Russian music what Donizetti

Gaetano Donizetti

Domenico Gaetano Maria Donizetti was an Italian composer from Bergamo, Lombardy. His best-known works are the operas L'elisir d'amore , Lucia di Lammermoor , and Don Pasquale , all in Italian, and the French operas La favorite and La fille du régiment...

and Bellini

Vincenzo Bellini

Vincenzo Salvatore Carmelo Francesco Bellini was an Italian opera composer. His greatest works are I Capuleti ed i Montecchi , La sonnambula , Norma , Beatrice di Tenda , and I puritani...

had done for Italian music. His return route took him through the Alps, and he stopped for a while in Vienna

Vienna

Vienna is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Austria and one of the nine states of Austria. Vienna is Austria's primary city, with a population of about 1.723 million , and is by far the largest city in Austria, as well as its cultural, economic, and political centre...

, where he heard the music of Franz Liszt

Franz Liszt

Franz Liszt ; ), was a 19th-century Hungarian composer, pianist, conductor, and teacher.Liszt became renowned in Europe during the nineteenth century for his virtuosic skill as a pianist. He was said by his contemporaries to have been the most technically advanced pianist of his age...

. He stayed for another five months in Berlin

Berlin

Berlin is the capital city of Germany and is one of the 16 states of Germany. With a population of 3.45 million people, Berlin is Germany's largest city. It is the second most populous city proper and the seventh most populous urban area in the European Union...

, during which time he studied composition under the distinguished teacher Siegfried Dehn

Siegfried Dehn

Siegfried Dehn was a German music theorist, editor, teacher and librarian.Born in Altona, Hamburg, Dehn was the son of a banker and learned to play the cello as a boy. Intent on becoming a diplomat, he studied law in Leipzig but also took music lessons from J.A. Dröbs...

. A Capriccio on Russian themes for piano duet and an unfinished Symphony on two Russian themes were important products of this period.

When word reached Mikhail Glinka of his father's death in 1834, he left Berlin and returned to Novospasskoye.

Middle years

A Life for the Tsar

A Life for the Tsar , as it is known in English, although its original name was Ivan Susanin is a "patriotic-heroic tragic opera" in four acts with an epilogue by Mikhail Glinka. The original Russian libretto, based on historical events, was written by Nestor Kukolnik, Georgy Fyodorovich Rozen,...

(1836), his naturally sweet disposition coarsened under the constant nagging of his wife and her mother. After separating, she would remarry, while Glinka moved in with his mother, and later his sister (Lyudmila Shestakova).

A Life for the Tsar was the first of Glinka's two great operas. It was originally entitled Ivan Susanin. Set in 1612, it tells the story of the Russian peasant and patriotic hero Ivan Susanin

Ivan Susanin

Ivan Susanin was a Russian folk hero and martyr of the early 17th century's Time of Troubles.-Evidence:In 1619, a certain Bogdan Sobinin from Domnino village near Kostroma received from Tsar Mikhail one half of Derevischi village. According to the extant royal charter, these lands were granted...

who sacrifices his life for the Tsar

Tsar

Tsar is a title used to designate certain European Slavic monarchs or supreme rulers. As a system of government in the Tsardom of Russia and Russian Empire, it is known as Tsarist autocracy, or Tsarism...

by leading astray a group of marauding Poles

Poles

thumb|right|180px|The state flag of [[Poland]] as used by Polish government and diplomatic authoritiesThe Polish people, or Poles , are a nation indigenous to Poland. They are united by the Polish language, which belongs to the historical Lechitic subgroup of West Slavic languages of Central Europe...

who were hunting him. The Tsar himself followed the work’s progress with interest and suggested the change in the title. It was a great success at its premiere on December 9, 1836, under the direction of Catterino Cavos

Catterino Cavos

Catterino Albertovich Cavos , born Catarino Camillo Cavos, was an Italian composer, organist and conductor settled in Russia...

, who had written an opera on the same subject in Italy. Although the music is still more Italianate than Russian, Glinka shows superb handling of the recitative

Recitative

Recitative , also known by its Italian name "recitativo" , is a style of delivery in which a singer is allowed to adopt the rhythms of ordinary speech...

which binds the whole work, and the orchestration

Orchestration

Orchestration is the study or practice of writing music for an orchestra or of adapting for orchestra music composed for another medium...

is masterly, foreshadowing the orchestral writing of later Russian composers. The Tsar rewarded Glinka for his work with a ring valued at 4000 ruble

Russian ruble

The ruble or rouble is the currency of the Russian Federation and the two partially recognized republics of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Formerly, the ruble was also the currency of the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union prior to their breakups. Belarus and Transnistria also use currencies with...

s. (During the Soviet era, the opera was staged under its original title Ivan Susanin).

Saint Petersburg Court Capella

The Saint Petersburg Court Capella is the oldest active Russian professional musical institution. Based in the city of Saint Petersburg, it was founded in 1479 by an order of Ivan III of Russia as the State Choir of Singing Dyaks. The insitution currently consists of a choir, an orchestra, and has...

, with a yearly salary of 25,000 roubles, and lodging at the court. In 1838, at the suggestion of the Tsar, he went off to Ukraine

Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It has an area of 603,628 km², making it the second largest contiguous country on the European continent, after Russia...

to gather new voices for the choir; the 19 new boys he found earned him another 1,500 roubles from the Tsar.

He soon embarked on his second opera: Ruslan and Lyudmila. The plot, based on the tale by Pushkin, was concocted in 15 minutes by Konstantin Bakhturin, a poet who was drunk at the time. Consequently the opera is a dramatic muddle, yet the quality of Glinka’s music is higher than in A Life for the Tsar. He uses a descending whole-tone-scale in the famous overture. This is associated with the villainous dwarf Chernomor who has abducted Lyudmila, daughter of the Prince of Kiev

Kiev

Kiev or Kyiv is the capital and the largest city of Ukraine, located in the north central part of the country on the Dnieper River. The population as of the 2001 census was 2,611,300. However, higher numbers have been cited in the press....

. There is much Italianate coloratura

Coloratura

Coloratura has several meanings. The word is originally from Italian, literally meaning "coloring", and derives from the Latin word colorare . When used in English, the term specifically refers to elaborate melody, particularly in vocal music and especially in operatic singing of the 18th and...

, and Act 3 contains several routine ballet numbers, but his great achievement in this opera lies in his use of folk melody which becomes thoroughly infused into the musical argument. Much of the borrowed folk material is oriental in origin. When it was first produced on 9 December 1842 it met with a cool reception, although subsequently it gained popularity.

Later years

Paris

Paris is the capital and largest city in France, situated on the river Seine, in northern France, at the heart of the Île-de-France region...

and Spain

Spain

Spain , officially the Kingdom of Spain languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Spain's official name is as follows:;;;;;;), is a country and member state of the European Union located in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula...

. In Spain, Glinka met Don Pedro Fernandez, who remained his secretary and companion for the last nine years of his life. In Paris, Berlioz conducted some excerpts from Glinka’s operas and wrote an appreciative article about him. Glinka in turn admired Berlioz’s music and resolved to compose some fantasies pittoresques for orchestra. Another visit to Paris followed in 1852 where he spent two years, living quietly and making frequent visits to the botanical and zoological gardens

Zoo

A zoological garden, zoological park, menagerie, or zoo is a facility in which animals are confined within enclosures, displayed to the public, and in which they may also be bred....

. From there he moved to Berlin where, after five months, he died suddenly on 15 February 1857, following a cold. He was buried in Berlin but a few months later his body was taken to Saint Petersburg and reinterred in the cemetery of the Alexander Nevsky Monastery.

Legacy

Alexander Serov

Alexander Nikolayevich Serov – was a Russian composer and music critic. He and his wife Valentina were the parents of painter Valentin Serov...

.

In 1884 Mitrofan Petrovich Belyayev founded the "Glinka prize", which was awarded annually. In the first years the winners included Borodin, Mily Balakirev, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Cesar Cui and Lyadov.

Outside Russia several of Glinka's orchestra

Orchestra

An orchestra is a sizable instrumental ensemble that contains sections of string, brass, woodwind, and percussion instruments. The term orchestra derives from the Greek ορχήστρα, the name for the area in front of an ancient Greek stage reserved for the Greek chorus...

l works have been fairly popular in concerts and recordings. Besides the well-known overture

Overture

Overture in music is the term originally applied to the instrumental introduction to an opera...

s to the operas (especially the brilliantly energetic overture to Ruslan), his major orchestral works include the symphonic poem Kamarinskaya (1848), based on Russian folk tunes, and two Spanish works, A Night in Madrid (1848, 1851) and Jota Aragonesa (1845).

Glinka also composed many art song

Art song

An art song is a vocal music composition, usually written for one voice with piano or orchestral accompaniment. By extension, the term "art song" is used to refer to the genre of such songs....

s, many piano pieces, and some chamber music.

A much lesser work that received some attention in the last decade was Glinka's "The Patriotic Song", supposedly written for a contest for a national anthem

National anthem

A national anthem is a generally patriotic musical composition that evokes and eulogizes the history, traditions and struggles of its people, recognized either by a nation's government as the official national song, or by convention through use by the people.- History :Anthems rose to prominence...

in 1833; the music was adopted as the national anthem of Russia

Russia

Russia or , officially known as both Russia and the Russian Federation , is a country in northern Eurasia. It is a federal semi-presidential republic, comprising 83 federal subjects...

during 1990–2000.

Three Russian conservatories are named after Glinka:

- Nizhny NovgorodNizhny NovgorodNizhny Novgorod , colloquially shortened to Nizhny, is, with the population of 1,250,615, the fifth largest city in Russia, ranking after Moscow, St. Petersburg, Novosibirsk, and Yekaterinburg...

State Conservatory http://www.uic.nnov.ru/abiturient/ngk/ - NovosibirskNovosibirskNovosibirsk is the third-largest city in Russia, after Moscow and Saint Petersburg, and the largest city of Siberia, with a population of 1,473,737 . It is the administrative center of Novosibirsk Oblast as well as of the Siberian Federal District...

State Conservatory http://www.conservatoire.ru/ - MagnitogorskMagnitogorskMagnitogorsk is a mining and industrial city in Chelyabinsk Oblast, Russia, located on the eastern side of the extreme southern extent of the Ural Mountains by the Ural River. Population: 418,545 ;...

State Conservatory http://www.magkmusic.com/

Soviet

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

astronomer Lyudmila Chernykh

Lyudmila Chernykh

Lyudmila Ivanovna Chernykh is a Russian, Ukrainian and Soviet astronomer.In 1959 she graduated from Irkutsk State Pedagogical University. Between 1959 and 1963 she worked in the 'Time and Frequency Laboratory' of the All-Union Research Institute of Physico-Technical and Radiotechnical Measurements...

named a minor planet

Minor planet

An asteroid group or minor-planet group is a population of minor planets that have a share broadly similar orbits. Members are generally unrelated to each other, unlike in an asteroid family, which often results from the break-up of a single asteroid...

2205 Glinka

2205 Glinka

2205 Glinka is a main-belt asteroid discovered on September 27, 1973 by L. I. Chernykh at the Crimean Astrophysical Observatory. It is named for the Russian composer Mikhail Glinka.- External links :*...

in his honor. It was discovered in 1973. A crater on Mercury is also named after him.

Works

Media

External links

- List of works

- Cylinder recording of a Glinka composition, from the Cylinder Preservation and Digitization ProjectCylinder Preservation and Digitization ProjectThe Cylinder Preservation and Digitization Project is a free digital collection maintained by the University of California, Santa Barbara Libraries with streaming and downloadable versions of over 10,000 phonograph cylinders manufactured between 1893 and the mid 1920s.- History :The project began...

at the University of California, Santa BarbaraUniversity of California, Santa BarbaraThe University of California, Santa Barbara, commonly known as UCSB or UC Santa Barbara, is a public research university and one of the 10 general campuses of the University of California system. The main campus is located on a site in Goleta, California, from Santa Barbara and northwest of Los...

Library. - Glinka — the author of Russian national anthem by K.Kovalev

- Leicestershire Schools Symphony Orchestra performs Russlan and Ludmilla overture A short video from 1998

- Chamber Music Sound-bites & Short biography

- Turgenev and Glinka (with music samples)