Charles Bertram

Encyclopedia

Charles Bertram was the author of the forged

manuscript De Situ Britanniae

("The Description of Britain"), a spurious history that was highly influential in the reconstruction of the history of Roman Britain

for over a century. It had a similar impact on the explanation of Scottish history

over the same period of time. He was otherwise a little-known writer, and his authorship of the forgery is his only modern notability. Bertram's motives are still unknown, as he never tried to profit directly from the forgery. For the remainder of his life, his notability was merely that he had found a valuable "lost" history of Britain and had made its contents public.

among the retinue of Princess Louisa

, daughter of George II who married Crown Prince

Frederick

of Denmark

in 1743 (he would become King three years later). The father established himself as a hosier, and Charles seemed to have benefited from the warm reception that Louisa and her retinue had received from the Danes. In 1747 Charles' petition to the Consistorium for entry to the University of Copenhagen

was granted, even though it should not have been granted, because he belonged to the Anglican Church

. He became a friend and protege of Hans Gramm, privy-counselor

and librarian to the King of Denmark, a relationship that would be important during subsequent events. In 1748 Bertram petitioned the king to be permitted to give public lectures on the English language, and he became a teacher of English

in the Royal Marine Academy at Copenhagen (some accounts say he was a professor, rather than a tutor of students; if so, that would be some years later, as he was a new undergraduate in 1747).

Bertram wrote a letter to the celebrated antiquarian

Bertram wrote a letter to the celebrated antiquarian

William Stukeley

in 1746, saying he had access to an old manuscript written by a medieval English monk named Richard of Westminster, and which contained much information on Roman Britain. When Stukeley responded, Bertram followed with another letter and included a letter from Gramm, which effectively served as a letter of introduction from a high-ranking Danish official who was widely known and respected in English universities. Bertram then sent a fragment of parchment to Stukeley, and it was verified as 400 years old by the keeper of the Cotton Library

. With the seeming endorsement of Gramm and a verified 400 year old sample, Stukeley concluded that a genuine manuscript existed and thereafter treated Bertram as reliable. By early 1749 Bertram had provided Stukeley with his copy of the manuscript and map, which were kept in the Arundel Library of the Royal Society.

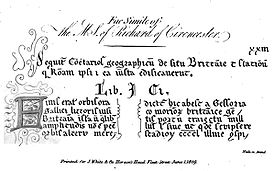

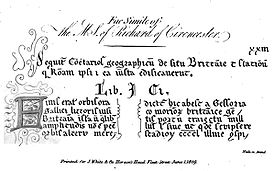

Stukeley, finding that a chronicler of the fourteenth century, Richard of Cirencester

, had also been an inmate of Westminster Abbey, identified him with Bertram's Richard of Westminster, and, in 1756, read an analysis of the discovery before the Society of Antiquaries

, which was published with a copy of Richard's map. In 1757 Bertram published at Copenhagen a volume entitled Rerum Gentium Historiae Antiquae Scriptores Tres. This contained the works of Gildas

and Nennius

and the full text of the forgery, and though Bertram's map did not correspond with that of Richard, Stukeley discarded the latter and adopted Bertram's concoction in his Itinerarium Curiosum posthumously published in 1776.

The uncritical acceptance of the forgery was widespread in Britain. While there were occasional questions as to the location of the original manuscript and map, there was no serious effort to evaluate the validity of Bertram's copy.

The end did not come until 1845, almost a century since the forgery's misinformation had been incorporated into nearly every British publication on ancient British history. In that year the German writer Karl Wex effectively challenged the validity of De Situ Britanniae in the Rheinisches Museum, which was translated into English and printed by the Gentleman's Magazine in October 1846. Further evidence of the falsity of De Situ Britanniae came out in the following years, and by 1870 it had been repeatedly debunked in great detail.

Forgery

Forgery is the process of making, adapting, or imitating objects, statistics, or documents with the intent to deceive. Copies, studio replicas, and reproductions are not considered forgeries, though they may later become forgeries through knowing and willful misrepresentations. Forging money or...

manuscript De Situ Britanniae

De Situ Britanniae

De Situ Britanniae is a fictional description of the peoples and places of ancient Britain. Purported to contain the account of a Roman general preserved in the manuscript of a fourteenth century English monk, it was considered the premier source of information on Roman Britain for more than a...

("The Description of Britain"), a spurious history that was highly influential in the reconstruction of the history of Roman Britain

Roman Britain

Roman Britain was the part of the island of Great Britain controlled by the Roman Empire from AD 43 until ca. AD 410.The Romans referred to the imperial province as Britannia, which eventually comprised all of the island of Great Britain south of the fluid frontier with Caledonia...

for over a century. It had a similar impact on the explanation of Scottish history

History of Scotland

The history of Scotland begins around 10,000 years ago, when humans first began to inhabit what is now Scotland after the end of the Devensian glaciation, the last ice age...

over the same period of time. He was otherwise a little-known writer, and his authorship of the forgery is his only modern notability. Bertram's motives are still unknown, as he never tried to profit directly from the forgery. For the remainder of his life, his notability was merely that he had found a valuable "lost" history of Britain and had made its contents public.

Early life

Charles Bertram was the son of an English silk dyer who migrated to CopenhagenCopenhagen

Copenhagen is the capital and largest city of Denmark, with an urban population of 1,199,224 and a metropolitan population of 1,930,260 . With the completion of the transnational Øresund Bridge in 2000, Copenhagen has become the centre of the increasingly integrating Øresund Region...

among the retinue of Princess Louisa

Louise of Great Britain

Louise of Great Britain was the youngest surviving daughter of George II of Great Britain and Caroline of Ansbach, and became queen consort of Denmark and Norway.-Early life:...

, daughter of George II who married Crown Prince

Crown Prince

A crown prince or crown princess is the heir or heiress apparent to the throne in a royal or imperial monarchy. The wife of a crown prince is also titled crown princess....

Frederick

Frederick V of Denmark

Frederick V was king of Denmark and Norway from 1746, son of Christian VI of Denmark and Sophia Magdalen of Brandenburg-Kulmbach.-Early life:...

of Denmark

Denmark

Denmark is a Scandinavian country in Northern Europe. The countries of Denmark and Greenland, as well as the Faroe Islands, constitute the Kingdom of Denmark . It is the southernmost of the Nordic countries, southwest of Sweden and south of Norway, and bordered to the south by Germany. Denmark...

in 1743 (he would become King three years later). The father established himself as a hosier, and Charles seemed to have benefited from the warm reception that Louisa and her retinue had received from the Danes. In 1747 Charles' petition to the Consistorium for entry to the University of Copenhagen

University of Copenhagen

The University of Copenhagen is the oldest and largest university and research institution in Denmark. Founded in 1479, it has more than 37,000 students, the majority of whom are female , and more than 7,000 employees. The university has several campuses located in and around Copenhagen, with the...

was granted, even though it should not have been granted, because he belonged to the Anglican Church

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

. He became a friend and protege of Hans Gramm, privy-counselor

Privy council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a nation, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the monarch's closest advisors to give confidential advice on...

and librarian to the King of Denmark, a relationship that would be important during subsequent events. In 1748 Bertram petitioned the king to be permitted to give public lectures on the English language, and he became a teacher of English

English language

English is a West Germanic language that arose in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of England and spread into what was to become south-east Scotland under the influence of the Anglian medieval kingdom of Northumbria...

in the Royal Marine Academy at Copenhagen (some accounts say he was a professor, rather than a tutor of students; if so, that would be some years later, as he was a new undergraduate in 1747).

The forgery

Antiquarian

An antiquarian or antiquary is an aficionado or student of antiquities or things of the past. More specifically, the term is used for those who study history with particular attention to ancient objects of art or science, archaeological and historic sites, or historic archives and manuscripts...

William Stukeley

William Stukeley

William Stukeley FRS, FRCP, FSA was an English antiquarian who pioneered the archaeological investigation of the prehistoric monuments of Stonehenge and Avebury, work for which he has been remembered as "probably... the most important of the early forerunners of the discipline of archaeology"...

in 1746, saying he had access to an old manuscript written by a medieval English monk named Richard of Westminster, and which contained much information on Roman Britain. When Stukeley responded, Bertram followed with another letter and included a letter from Gramm, which effectively served as a letter of introduction from a high-ranking Danish official who was widely known and respected in English universities. Bertram then sent a fragment of parchment to Stukeley, and it was verified as 400 years old by the keeper of the Cotton Library

Cotton library

The Cotton or Cottonian library was collected privately by Sir Robert Bruce Cotton M.P. , an antiquarian and bibliophile, and was the basis of the British Library...

. With the seeming endorsement of Gramm and a verified 400 year old sample, Stukeley concluded that a genuine manuscript existed and thereafter treated Bertram as reliable. By early 1749 Bertram had provided Stukeley with his copy of the manuscript and map, which were kept in the Arundel Library of the Royal Society.

Stukeley, finding that a chronicler of the fourteenth century, Richard of Cirencester

Richard of Cirencester

Richard of Cirencester , historical writer, was a member of the Benedictine abbey at Westminster, and his name first appears on the chamberlain's list of the monks of that foundation drawn up in the year 1355....

, had also been an inmate of Westminster Abbey, identified him with Bertram's Richard of Westminster, and, in 1756, read an analysis of the discovery before the Society of Antiquaries

Society of Antiquaries of London

The Society of Antiquaries of London is a learned society "charged by its Royal Charter of 1751 with 'the encouragement, advancement and furtherance of the study and knowledge of the antiquities and history of this and other countries'." It is based at Burlington House, Piccadilly, London , and is...

, which was published with a copy of Richard's map. In 1757 Bertram published at Copenhagen a volume entitled Rerum Gentium Historiae Antiquae Scriptores Tres. This contained the works of Gildas

Gildas

Gildas was a 6th-century British cleric. He is one of the best-documented figures of the Christian church in the British Isles during this period. His renowned learning and literary style earned him the designation Gildas Sapiens...

and Nennius

Nennius

Nennius was a Welsh monk of the 9th century.He has traditionally been attributed with the authorship of the Historia Brittonum, based on the prologue affixed to that work, This attribution is widely considered a secondary tradition....

and the full text of the forgery, and though Bertram's map did not correspond with that of Richard, Stukeley discarded the latter and adopted Bertram's concoction in his Itinerarium Curiosum posthumously published in 1776.

The uncritical acceptance of the forgery was widespread in Britain. While there were occasional questions as to the location of the original manuscript and map, there was no serious effort to evaluate the validity of Bertram's copy.

The end did not come until 1845, almost a century since the forgery's misinformation had been incorporated into nearly every British publication on ancient British history. In that year the German writer Karl Wex effectively challenged the validity of De Situ Britanniae in the Rheinisches Museum, which was translated into English and printed by the Gentleman's Magazine in October 1846. Further evidence of the falsity of De Situ Britanniae came out in the following years, and by 1870 it had been repeatedly debunked in great detail.