Charles Henry Pepys Harington

Encyclopedia

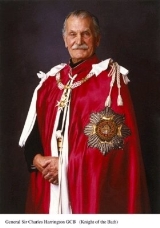

General

Sir Charles Henry Pepys Harington GCB

, CBE

, DSO

, MC

(1910 – 13 February 2007) was an officer in the British Army

. He served in the British Expeditionary Force

and in Normandy

in the Second World War. He was later Commander-in-Chief of the three-service Middle East Command

from 1963 to 1965, based at Aden

. He ended his Army career as Chief of Personnel and Logistics at the UK Ministry of Defence from 1968 to 1971.

, into a military family. He was related to General Sir Charles Harington Harington

, the commander in Constantinople

in 1922 during the Chanak crisis

. His father, Lieutenant-Colonel Herbert Hastings Harington, an officer in the Indian Army

, was killed in Mesopotamia

in 1916, and Harington and his two sisters were raised by their widowed mother.

He was educated at Malvern College

and Sandhurst

. He was commissioned into the 22nd (Cheshire) Regiment in 1930. He excelled at athletics, holding the Army record for the 440 yard hurdles and competing for the Army against the other services. He was captain of the 2nd Battalion's athletics team, winning the Army Inter-Unit Team Athletic Championship in 1937, 1938 and 1939. He was the adjutant of the 2nd Battalion from 1936 to 1939.

in France and Belgium in 1939 and 1940, commanding a machinegun company of the 2nd Battalion of the Cheshire Regiment in the 1st Infantry Division. During the retreat from the River Dyle in the face of the German blitzkrieg

in May 1940, his company formed part of the division's rearguard, supporting the 13th/18th Royal Hussars and 21st Anti-Tank Regiment of the Royal Artillery

. He was awarded the Military Cross

for his actions, and was evacuated from Dunkirk.

He spent most of the Second World War on staff appointments, and married Victoire Marion Williams-Freeman in 1942. Promoted to lieutenant colonel, he took command of the 1st Battalion, Manchester Regiment, in March 1944. The unit was poorly trained and virtually unfit for duty, but Harington quickly brought it to full combat readiness. The battalion fought well in Normandy

after D-Day

, and Harington was awarded the DSO.

in Camberley

for two years, before joining the British Military Mission in Greece during the Greek Civil War

. He commanded the 1st Battalion, Parachute Regiment from 1949 to 1951. He then served as military assistant to two Chief of the Imperial General Staff, Field Marshal Viscount Slim

and General Sir John Harding, before spending time at Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe

in France.

Promoted to Brigadier

, he commanded the 49th Infantry Brigade in Kenya

in 1955 and 1956, during the Mau Mau Uprising

. He was appointed CBE in 1957, and was commandant of the School of Infantry

in Warminster

in 1958. He was promoted to Major General

, and took command of the 3rd Division in 1959. He then became commandant of the Staff College, Camberley

in 1961. He succeeded Major General Tom Brodie as Colonel of the Cheshire Regiment

in January 1962, remaining the regiment's Colonel until 1968.

in May 1963, with responsibility for an area extending from the Persian Gulf

to East Africa

. In January 1964, he had to deal with mutinous

battalions in newly-independent Kenya

, Tanganyika

and Uganda

, formerly part of the King's African Rifles

. He was knighted in 1964.

He then had to deal with insurgency

of Haushabi and Radfan

tribes in the Western Aden Protectorate on the road between Aden and Dhala. The deployment of British forces bolstered support for the Front for the Liberation of South Yemen, triggering a campaign of violence in Aden itself.

Sir Arthur Charles

, the Speaker of the nascent National Council, was murdered outside his house in Crater

in September 1965. Direct British rule

was reimposed when the President of the Council, Abdull al-Qawi Mecca-wi, refused to condemn the killing. The subsequent counterinsurgency operations failed: the Aden Police were infiltrated, and officers in the local Special Branch

were killed. In 1966, the British government, led by Harold Wilson

, decided to withdraw British forces from Aden and the Protectorates by 1968, by which time Harington had returned to the UK.

General to the Queen from 1969 to 1971. He retired from the Army in 1971.

In retirement, he was president of the Combined Cadet Force Association from 1971 to 1980, and chairman of the Governors of the Royal Star and Garter Home in Richmond for disabled ex-servicemen from 1972 to 1980. He was a vice-president of Battersea Dogs' Home, and president of the Milocarian (Tri-Service) Athletic Club from 1966 to 1999. He also enjoyed sailing, and was president of the Hurlingham Club

for over 25 years.

His wife died in 2000. He was survived by their son and two daughters, and he has six grandchildren.

General

A general officer is an officer of high military rank, usually in the army, and in some nations, the air force. The term is widely used by many nations of the world, and when a country uses a different term, there is an equivalent title given....

Sir Charles Henry Pepys Harington GCB

Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate mediæval ceremony for creating a knight, which involved bathing as one of its elements. The knights so created were known as Knights of the Bath...

, CBE

Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is an order of chivalry established on 4 June 1917 by George V of the United Kingdom. The Order comprises five classes in civil and military divisions...

, DSO

Distinguished Service Order

The Distinguished Service Order is a military decoration of the United Kingdom, and formerly of other parts of the British Commonwealth and Empire, awarded for meritorious or distinguished service by officers of the armed forces during wartime, typically in actual combat.Instituted on 6 September...

, MC

Military Cross

The Military Cross is the third-level military decoration awarded to officers and other ranks of the British Armed Forces; and formerly also to officers of other Commonwealth countries....

(1910 – 13 February 2007) was an officer in the British Army

British Army

The British Army is the land warfare branch of Her Majesty's Armed Forces in the United Kingdom. It came into being with the unification of the Kingdom of England and Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707. The new British Army incorporated Regiments that had already existed in England...

. He served in the British Expeditionary Force

British Expeditionary Force (World War II)

The British Expeditionary Force was the British force in Europe from 1939–1940 during the Second World War. Commanded by General Lord Gort, the BEF constituted one-tenth of the defending Allied force....

and in Normandy

Normandy

Normandy is a geographical region corresponding to the former Duchy of Normandy. It is in France.The continental territory covers 30,627 km² and forms the preponderant part of Normandy and roughly 5% of the territory of France. It is divided for administrative purposes into two régions:...

in the Second World War. He was later Commander-in-Chief of the three-service Middle East Command

Middle East Command

The Middle East Command was a British Army Command established prior to the Second World War in Egypt. Its primary role was to command British land forces and co-ordinate with the relevant naval and air commands to defend British interests in the Middle East and eastern Mediterranean region.The...

from 1963 to 1965, based at Aden

Aden

Aden is a seaport city in Yemen, located by the eastern approach to the Red Sea , some 170 kilometres east of Bab-el-Mandeb. Its population is approximately 800,000. Aden's ancient, natural harbour lies in the crater of an extinct volcano which now forms a peninsula, joined to the mainland by a...

. He ended his Army career as Chief of Personnel and Logistics at the UK Ministry of Defence from 1968 to 1971.

Early life and career

Harington was born in Tunbridge WellsRoyal Tunbridge Wells

Royal Tunbridge Wells is a town in west Kent, England, about south-east of central London by road, by rail. The town is close to the border of the county of East Sussex...

, into a military family. He was related to General Sir Charles Harington Harington

Charles Harington Harington

General Sir Charles Harington Harington GCB, GBE, DSO, DCL , was a British Army officer most noted for his service during the First World War and Chanak crisis...

, the commander in Constantinople

Constantinople

Constantinople was the capital of the Roman, Eastern Roman, Byzantine, Latin, and Ottoman Empires. Throughout most of the Middle Ages, Constantinople was Europe's largest and wealthiest city.-Names:...

in 1922 during the Chanak crisis

Chanak Crisis

The Chanak Crisis, also called Chanak Affair in September 1922 was the threatened attack by Turkish troops on British and French troops stationed near Çanakkale to guard the Dardanelles neutral zone. The Turkish troops had recently defeated Greek forces and recaptured İzmir...

. His father, Lieutenant-Colonel Herbert Hastings Harington, an officer in the Indian Army

Indian Army

The Indian Army is the land based branch and the largest component of the Indian Armed Forces. With about 1,100,000 soldiers in active service and about 1,150,000 reserve troops, the Indian Army is the world's largest standing volunteer army...

, was killed in Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a toponym for the area of the Tigris–Euphrates river system, largely corresponding to modern-day Iraq, northeastern Syria, southeastern Turkey and southwestern Iran.Widely considered to be the cradle of civilization, Bronze Age Mesopotamia included Sumer and the...

in 1916, and Harington and his two sisters were raised by their widowed mother.

He was educated at Malvern College

Malvern College

Malvern College is a coeducational independent school located on a 250 acre campus near the town centre of Malvern, Worcestershire in England. Founded on 25 January 1865, until 1992, the College was a secondary school for boys aged 13 to 18...

and Sandhurst

Royal Military Academy Sandhurst

The Royal Military Academy Sandhurst , commonly known simply as Sandhurst, is a British Army officer initial training centre located in Sandhurst, Berkshire, England...

. He was commissioned into the 22nd (Cheshire) Regiment in 1930. He excelled at athletics, holding the Army record for the 440 yard hurdles and competing for the Army against the other services. He was captain of the 2nd Battalion's athletics team, winning the Army Inter-Unit Team Athletic Championship in 1937, 1938 and 1939. He was the adjutant of the 2nd Battalion from 1936 to 1939.

Second World War

He joined the British Expeditionary ForceBritish Expeditionary Force (World War II)

The British Expeditionary Force was the British force in Europe from 1939–1940 during the Second World War. Commanded by General Lord Gort, the BEF constituted one-tenth of the defending Allied force....

in France and Belgium in 1939 and 1940, commanding a machinegun company of the 2nd Battalion of the Cheshire Regiment in the 1st Infantry Division. During the retreat from the River Dyle in the face of the German blitzkrieg

Blitzkrieg

For other uses of the word, see: Blitzkrieg Blitzkrieg is an anglicized word describing all-motorised force concentration of tanks, infantry, artillery, combat engineers and air power, concentrating overwhelming force at high speed to break through enemy lines, and, once the lines are broken,...

in May 1940, his company formed part of the division's rearguard, supporting the 13th/18th Royal Hussars and 21st Anti-Tank Regiment of the Royal Artillery

Royal Artillery

The Royal Regiment of Artillery, commonly referred to as the Royal Artillery , is the artillery arm of the British Army. Despite its name, it comprises a number of regiments.-History:...

. He was awarded the Military Cross

Military Cross

The Military Cross is the third-level military decoration awarded to officers and other ranks of the British Armed Forces; and formerly also to officers of other Commonwealth countries....

for his actions, and was evacuated from Dunkirk.

He spent most of the Second World War on staff appointments, and married Victoire Marion Williams-Freeman in 1942. Promoted to lieutenant colonel, he took command of the 1st Battalion, Manchester Regiment, in March 1944. The unit was poorly trained and virtually unfit for duty, but Harington quickly brought it to full combat readiness. The battalion fought well in Normandy

Normandy

Normandy is a geographical region corresponding to the former Duchy of Normandy. It is in France.The continental territory covers 30,627 km² and forms the preponderant part of Normandy and roughly 5% of the territory of France. It is divided for administrative purposes into two régions:...

after D-Day

D-Day

D-Day is a term often used in military parlance to denote the day on which a combat attack or operation is to be initiated. "D-Day" often represents a variable, designating the day upon which some significant event will occur or has occurred; see Military designation of days and hours for similar...

, and Harington was awarded the DSO.

Post-war service

Harington was rapidly promoted after the war. He was General Staff Officer Grade 1 at the headquarters of the 53rd (Welsh) Division, then served as an instructor at the Staff CollegeStaff college

Staff colleges train military officers in the administrative, staff and policy aspects of their profession. It is usual for such training to occur at several levels in a career...

in Camberley

Camberley

Camberley is a town in Surrey, England, situated 31 miles southwest of central London, in the corridor between the M3 and M4 motorways. The town lies close to the borders of both Hampshire and Berkshire; the boundaries intersect on the western edge of the town where all three counties...

for two years, before joining the British Military Mission in Greece during the Greek Civil War

Greek Civil War

The Greek Civil War was fought from 1946 to 1949 between the Greek governmental army, backed by the United Kingdom and United States, and the Democratic Army of Greece , the military branch of the Greek Communist Party , backed by Bulgaria, Yugoslavia and Albania...

. He commanded the 1st Battalion, Parachute Regiment from 1949 to 1951. He then served as military assistant to two Chief of the Imperial General Staff, Field Marshal Viscount Slim

William Slim, 1st Viscount Slim

Field Marshal William Joseph "Bill"'Slim, 1st Viscount Slim, KG, GCB, GCMG, GCVO, GBE, DSO, MC, KStJ was a British military commander and the 13th Governor-General of Australia....

and General Sir John Harding, before spending time at Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe

Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe

Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe is the central command of NATO military forces. It is located at Casteau, north of the Belgian city of Mons...

in France.

Promoted to Brigadier

Brigadier (United Kingdom)

Brigadier is a senior rank in the British Army and the Royal Marines.Brigadier is the superior rank to Colonel, but subordinate to Major-General....

, he commanded the 49th Infantry Brigade in Kenya

Kenya

Kenya , officially known as the Republic of Kenya, is a country in East Africa that lies on the equator, with the Indian Ocean to its south-east...

in 1955 and 1956, during the Mau Mau Uprising

Mau Mau Uprising

The Mau Mau Uprising was a military conflict that took place in Kenya between 1952 and 1960...

. He was appointed CBE in 1957, and was commandant of the School of Infantry

School of Infantry

A School of Infantry provides training in weapons and infantry tactics to infantrymen of a nation's military forces.Schools of infantry include: Australia*Australian Army - School of Infantry, Lone Pine Barracks at Singleton, NSW. France...

in Warminster

Warminster

Warminster is a town in western Wiltshire, England, by-passed by the A36, and near Frome and Westbury. It has a population of about 17,000. The River Were runs through the town and can be seen running through the middle of the town park. The Minster Church of St Denys sits on the River Were...

in 1958. He was promoted to Major General

Major General

Major general or major-general is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. A major general is a high-ranking officer, normally subordinate to the rank of lieutenant general and senior to the ranks of brigadier and brigadier general...

, and took command of the 3rd Division in 1959. He then became commandant of the Staff College, Camberley

Staff College, Camberley

Staff College, Camberley, Surrey, was a staff college for the British Army from 1802 to 1997, with periods of closure during major wars. In 1997 it was merged into the new Joint Services Command and Staff College.-Origins:...

in 1961. He succeeded Major General Tom Brodie as Colonel of the Cheshire Regiment

Cheshire Regiment

The Cheshire Regiment was an infantry regiment of the British Army, part of the Prince of Wales' Division.The regiment was created in 1881 as part of the Childers reforms by the linking of the 22nd Regiment of Foot and the militia and rifle volunteers of Cheshire...

in January 1962, remaining the regiment's Colonel until 1968.

Aden

Promoted to lieutenant general, he was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the three-service Middle East CommandMiddle East Command

The Middle East Command was a British Army Command established prior to the Second World War in Egypt. Its primary role was to command British land forces and co-ordinate with the relevant naval and air commands to defend British interests in the Middle East and eastern Mediterranean region.The...

in May 1963, with responsibility for an area extending from the Persian Gulf

Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf, in Southwest Asia, is an extension of the Indian Ocean located between Iran and the Arabian Peninsula.The Persian Gulf was the focus of the 1980–1988 Iran-Iraq War, in which each side attacked the other's oil tankers...

to East Africa

East Africa

East Africa or Eastern Africa is the easterly region of the African continent, variably defined by geography or geopolitics. In the UN scheme of geographic regions, 19 territories constitute Eastern Africa:...

. In January 1964, he had to deal with mutinous

Mutiny

Mutiny is a conspiracy among members of a group of similarly situated individuals to openly oppose, change or overthrow an authority to which they are subject...

battalions in newly-independent Kenya

Kenya

Kenya , officially known as the Republic of Kenya, is a country in East Africa that lies on the equator, with the Indian Ocean to its south-east...

, Tanganyika

Tanganyika

Tanganyika , later formally the Republic of Tanganyika, was a sovereign state in East Africa from 1961 to 1964. It was situated between the Indian Ocean and the African Great Lakes of Lake Victoria, Lake Malawi and Lake Tanganyika...

and Uganda

Uganda

Uganda , officially the Republic of Uganda, is a landlocked country in East Africa. Uganda is also known as the "Pearl of Africa". It is bordered on the east by Kenya, on the north by South Sudan, on the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, on the southwest by Rwanda, and on the south by...

, formerly part of the King's African Rifles

King's African Rifles

The King's African Rifles was a multi-battalion British colonial regiment raised from the various British possessions in East Africa from 1902 until independence in the 1960s. It performed both military and internal security functions within the East African colonies as well as external service as...

. He was knighted in 1964.

He then had to deal with insurgency

Insurgency

An insurgency is an armed rebellion against a constituted authority when those taking part in the rebellion are not recognized as belligerents...

of Haushabi and Radfan

Radfan

Radfan or the Radfan Hills is a region of the Republic of Yemen. In the 1960s, the area was part of a British protectorate of Dhala and was the site of intense fighting during the Aden Emergency...

tribes in the Western Aden Protectorate on the road between Aden and Dhala. The deployment of British forces bolstered support for the Front for the Liberation of South Yemen, triggering a campaign of violence in Aden itself.

Sir Arthur Charles

Arthur Charles

Arthur Charles received his religious training at the Christ the King Seminary and was ordained a priest of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Karachi.From 2005 to 2009 he served as assistant parish priest at St. Jude's Parish, Karachi....

, the Speaker of the nascent National Council, was murdered outside his house in Crater

Crater (Yemen)

Crater, also Kraytar, is one of the unofficial names of the oldest districts of the port city of Aden. Its official name is Seera . It is situated in a crater of an ancient volcano which forms the Shamsan Mountains...

in September 1965. Direct British rule

Direct Rule

Direct rule was the term given, during the late 20th and early 21st centuries, to the administration of Northern Ireland directly from Westminster, seat of United Kingdom government...

was reimposed when the President of the Council, Abdull al-Qawi Mecca-wi, refused to condemn the killing. The subsequent counterinsurgency operations failed: the Aden Police were infiltrated, and officers in the local Special Branch

Special Branch

Special Branch is a label customarily used to identify units responsible for matters of national security in British and Commonwealth police forces, as well as in the Royal Thai Police...

were killed. In 1966, the British government, led by Harold Wilson

Harold Wilson

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx, KG, OBE, FRS, FSS, PC was a British Labour Member of Parliament, Leader of the Labour Party. He was twice Prime Minister of the United Kingdom during the 1960s and 1970s, winning four general elections, including a minority government after the...

, decided to withdraw British forces from Aden and the Protectorates by 1968, by which time Harington had returned to the UK.

Late career

Harington returned from Aden in 1966 to take up the position of Deputy Chief of the Imperial General Staff. He was promoted to general in 1968, and became Chief of Personnel and Logistics at the UK Ministry of Defence. He was appointed GCB in 1969, and was an Aide-de-campAide-de-camp

An aide-de-camp is a personal assistant, secretary, or adjutant to a person of high rank, usually a senior military officer or a head of state...

General to the Queen from 1969 to 1971. He retired from the Army in 1971.

In retirement, he was president of the Combined Cadet Force Association from 1971 to 1980, and chairman of the Governors of the Royal Star and Garter Home in Richmond for disabled ex-servicemen from 1972 to 1980. He was a vice-president of Battersea Dogs' Home, and president of the Milocarian (Tri-Service) Athletic Club from 1966 to 1999. He also enjoyed sailing, and was president of the Hurlingham Club

Hurlingham Club

The Hurlingham Club is an exclusive sports club in Fulham in southwest London, England. The club, founded in 1869, is situated by the River Thames in Fulham, West London, and has a Georgian clubhouse set in of grounds...

for over 25 years.

His wife died in 2000. He was survived by their son and two daughters, and he has six grandchildren.