Chinese written language

Encyclopedia

Written Chinese comprises Chinese characters (漢字/汉字 hànzì) used to represent the Chinese language

, and the rules about how they are arranged and punctuated. Chinese characters do not constitute an alphabet or a compact syllabary

. Rather, the writing system is roughly logosyllabic; that is, a character generally represents one syllable

of spoken Chinese and may be a word on its own or a part of a polysyllabic word. The characters themselves are often composed of parts that may represent physical objects, abstract notions, or pronunciation.

Various current Chinese characters have been traced back to the late 商 Shāng Dynasty

about 1200–1050 BCE, but the process of creating characters is thought to have begun some centuries earlier. After a period of variation and evolution, Chinese characters were standardized under the 秦 Qín dynasty

(221–206 BCE). Over the millennia, these characters have evolved into well-developed styles of Chinese calligraphy.

Some Chinese characters have been adopted as part of the writing systems of other East Asian languages, such as Japanese

and Korean

. Literacy requires the memorization of a great many characters: Educated Chinese know about 4,000; educated Japanese know about half that many. The large number of Chinese characters has in part led to the adoption of Western alphabets as an auxiliary means of representing Chinese.

The common belief that all Chinese varieties are mutually comprehensible when written is false. Although Chinese speakers in disparate dialect groups are able to communicate through writing, this is largely due to the fact non-Mandarin speakers write in Mandarin or in a heavily Mandarin-influenced form, rather than in a form that faithfully represents their spoken language. , and its written form

is quite different from written Mandarin. Characters are chosen to represent Cantonese words based on etymology, and may differ greatly in their meaning as compared to modern Mandarin. In addition, many Cantonese characters are archaic in a Mandarin context, and hundreds (perhaps thousands) of new characters have been created specifically to represent Cantonese-only words (e.g. borrowed words and grammatical particles).

Written Chinese is not based on an alphabet or a compact syllabary. Instead, Chinese characters are glyphs whose components may depict objects or represent abstract notions. Occasionally a character consists of only one component; more commonly two or more components are combined to form more complex characters, using a variety of different principles. The best known exposition of Chinese character composition is the 說文解字/说文解字 Shuōwén Jiězì

, compiled by 許慎/许慎 Xǔ Shèn

around 120 CE. Since Xu Shen did not have access to Chinese characters in their earliest forms, his analysis cannot always be taken as authoritative. Nonetheless, no later work has supplanted the Shuowen Jiezi in terms of breadth, and it is still relevant to etymological research today.

According to the Shuowen Jiezi, Chinese characters are developed on six basic principles. (These principles, though popularized by the Shuowen Jiezi, were developed earlier; the oldest known mention of them is in the 周禮/周礼 Zhōulǐ—literally, Rites of Zhou—a text from about 150 BCE.) The first two principles produce simple characters, known as 文 wén:

The remaining four principles produce complex characters historically called 字 zì (although this term is now generally used to refer to all characters, whether simple or complex). Of these four, two construct characters from simpler parts:

In contrast to the popular conception of Chinese as a primarily pictographic or ideographic language, the vast majority of Chinese characters (about 95 percent of the characters in the Shuowen Jiezi) are constructed as either logical aggregates or, more often, phonetic complexes. In fact, some phonetic complexes were originally simple pictographs that were later augmented by the addition of a semantic root. An example is 炷 zhù "candle" (now archaic, meaning "lampwick"), which was originally a pictograph 主, a character that is now pronounced zhǔ and means "host". The character 火 huǒ "fire" was added to indicate that the meaning is fire-related.

The last two principles do not produce new written forms; instead, they transfer new meanings to existing forms:

Chinese characters are written to fit into a square, even when composed of two simpler forms written side-by-side or top-to-bottom. In such cases, each form is compressed to fit the entire character into a square.

There are eight basic rules of stroke order in writing a Chinese character:

These rules do not strictly apply to every situation and are occasionally violated.

Chinese characters conform to a roughly square frame and are not usually linked to one another, so they can be written in any direction in a square grid. Traditionally, Chinese is written in vertical columns from top to bottom; the first column is on the right side of the page, and the text runs toward the left. Text written in Classical Chinese also uses little or no punctuation. In such cases, sentence and phrase breaks are determined by context and rhythm.

Chinese characters conform to a roughly square frame and are not usually linked to one another, so they can be written in any direction in a square grid. Traditionally, Chinese is written in vertical columns from top to bottom; the first column is on the right side of the page, and the text runs toward the left. Text written in Classical Chinese also uses little or no punctuation. In such cases, sentence and phrase breaks are determined by context and rhythm.

In modern times, the familiar Western layout of horizontal rows from left to right, read from the top of the page to the bottom, has become more popular, especially in the People's Republic of China

(mainland China), where the government mandated left-to-right writing in 1955. The Republic of China

(Taiwan

) followed suit in 2004. The use of punctuation has also become more common, whether the text is written in columns or rows. The punctuation marks are clearly influenced by their Western counterparts, although some marks are particular to Asian languages: for example, the double and single quotation marks (『 』 and 「 」); the hollow period (。), which is otherwise used just like an ordinary period; and a special kind of comma called an enumeration comma (、), which is used to separate items in a list, as opposed to clauses in a sentence.

Signs

are a particularly challenging aspect of written Chinese layout, since they can be written either left to right or right to left (the latter can be thought of as the traditional layout with each "column" being one character high), as well as from top to bottom. It is not uncommon to encounter all three orientations on signs on neighboring stores.

, an archaeological site in the 河南 Hénán

province of China, for an early form of Chinese writing. Some symbols were found that bear striking resemblance to certain modern characters, such as 目 mù "eye". Since the Jiahu site dates from about 6600 BCE, it predates the earliest confirmed Chinese writing by about 4,000 years. The nature of this finding—whether it represents true writing (that is, a general mechanism for expression) or simply proto-writing (which comprises a limited set of symbols)—is still controversial. Critics contend that if the Jiahu finding really represented a direct ancestor of modern Chinese writing, it would indicate that Chinese writing remained relatively static for three millennia, at a time when China was sparsely populated.

The first indisputable examples of Chinese writing, dating back to the Shāng Dynasty

The first indisputable examples of Chinese writing, dating back to the Shāng Dynasty

in the latter half of the second millennium BCE, were found on oracle bones, primarily ox scapulae and turtle shells, originally used for divination. Characters were inscribed on the bones in order to frame a question; the bones were then heated over a fire and the resulting cracks were interpreted to determine the answer. Such characters are called 甲骨文 jiǎgǔwén "shell-bone script" or oracle bone script

.

After the Shāng Dynasty, Chinese writing evolved into the form found on bronzeware made during the Western 周 Zhōu Dynasty

After the Shāng Dynasty, Chinese writing evolved into the form found on bronzeware made during the Western 周 Zhōu Dynasty

(c 1066–770 BCE) and the Spring and Autumn Period (770–476 BCE), a kind of writing called 金文 jīnwén "metal script". Jinwen characters are less angular and angularized than the oracle bone script. Later, in the Warring States Period

(475–221 BCE), the script became still more regular, and settled on a form, called 六國文字/六国文字 liùguó wénzì "script of the six states", that Xu Shen used as source material in the Shuowen Jiezi. These characters were later embellished and stylized to yield the 篆書/篆书 zhuànshū seal script

, which represents the oldest form of Chinese characters still in modern use. They are used principally for signature seals, or chops

, which are often used in place of a signature for Chinese documents and artwork. 李斯 Lǐ Sī

promulgated the seal script as the standard throughout the empire during the Qin dynasty

, then newly unified.

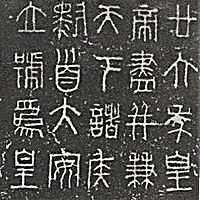

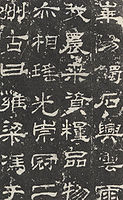

Seal script in turn evolved into the other surviving writing styles; the first writing style to follow was the clerical script. The development of such a style can be attributed to those of the Qin Dynasty who were seeking to create a convenient form of written characters for daily usage. In general, clerical script characters are "flat" in appearance, being wider than the seal script, which tends to be taller than it is wide. Compared with the seal script, clerical script characters are strikingly rectilinear. In running script (行書/行书 xíngshū), a semi-cursive form, the character elements begin to run into each other, although the characters themselves generally remain separate.

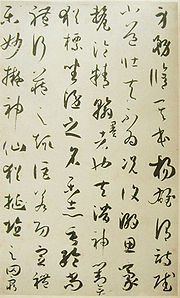

Running script eventually evolved into grass script (草書/草书 cǎoshū), a fully cursive form, in which the characters are often entirely unrecognizable by their canonical forms. Grass script gives the impression of anarchy in its appearance, and there is indeed considerable freedom on the part of the calligrapher, but this freedom is circumscribed by conventional "abbreviations" in the forms of the characters. Regular script

(楷書/楷书 kǎishū), a non-cursive form, is the most widely recognized script. In regular script, each stroke of each character is clearly drawn out from the others. Even though both the running and grass scripts appear to be derived as semi-cursive and cursive variants of regular script, it is in fact the regular script that was the last to develop.

Regular script is considered the archetype for Chinese writing, and forms the basis for most printed forms. In addition, regular script imposes a stroke order, which must be followed in order for the characters to be written correctly. (Strictly speaking, this stroke order applies to the clerical, running, and grass scripts as well, but especially in the running and grass scripts, this order is occasionally deviated from.) Thus, for instance, the character 木 mù "wood" must be written starting with the horizontal stroke, drawn from left to right; next, the vertical stroke, from top to bottom, with a small hook toward the upper left at the end; next, the left diagonal stroke, from top to bottom; and lastly the right diagonal stroke, from top to bottom.

The simplified forms have also been criticized for being inconsistent. For instance, traditional 讓 ràng "allow" is simplified to 让, in which the phonetic on the right side is reduced from 17 strokes to just three. (The speech radical on the left has also been simplified.) However, the same phonetic is used in its full form, even in simplified Chinese, in such characters as 壤 rǎng "soil" and 齉 nàng "snuffle"; these forms remained uncontracted because they were relatively uncommon and would therefore represent a negligible stroke reduction. On the other hand, some simplified forms are simply calligraphic abbreviations of long standing, as for example 万 wàn "ten thousand

", for which the traditional Chinese form is 萬.

Simplified Chinese is standard in the People's Republic of China, Singapore

, and Malaysia. Traditional Chinese is retained in Hong Kong

, Taiwan, Macau

and overseas Chinese

communities (except Singapore

and Malaysia). Throughout this article, Chinese text is given in both simplified and traditional forms when they differ, with the traditional forms being given first.

At the inception of written Chinese, spoken Chinese was monosyllabic; that is, Chinese words expressing independent concepts (objects, actions, relations, etc.) were usually one syllable. Each written character corresponded to one monosyllabic word. The spoken language has since become polysyllabic, but because modern polysyllabic words are usually composed of older monosyllabic words, Chinese characters have always been used to represent individual Chinese syllables.

At the inception of written Chinese, spoken Chinese was monosyllabic; that is, Chinese words expressing independent concepts (objects, actions, relations, etc.) were usually one syllable. Each written character corresponded to one monosyllabic word. The spoken language has since become polysyllabic, but because modern polysyllabic words are usually composed of older monosyllabic words, Chinese characters have always been used to represent individual Chinese syllables.

For over two thousand years, the prevailing written standard was a vocabulary and syntax rooted in Chinese as spoken around the time of Confucius

(about 500 BCE), called Classical Chinese

, or 文言文 wényánwén. Over the centuries, Classical Chinese gradually acquired some of its grammar and character senses from the various dialects. This accretion was generally slow and minor; however, by the 20th century, Classical Chinese was distinctly different from any contemporary dialect, and had to be learned separately. Once learned, it was a common medium for communication between people speaking different dialects, many of which were mutually unintelligible by the end of the first millennium CE. A Mandarin speaker might say yī, a Cantonese

jat1, and a Hokkienese tsit, but all three will understand the character 一 "one".

Chinese dialects vary not only by pronunciation, but also, to a lesser extent, vocabulary and grammar. Modern written Chinese, which replaced Classical Chinese as the written standard as an indirect result of the May Fourth Movement

of 1919, is not technically bound to any single dialect; however, it most nearly represents the vocabulary and syntax of Mandarin, by far the most widespread Chinese dialect in terms of both geographical area and number of speakers. This version of written Chinese is called Vernacular Chinese

, or 白話/白话 báihuà (literally, "plain speech"). Despite its ties to the dominant Mandarin dialect, Vernacular Chinese also permits some communication between people of different dialects, limited by the fact that Vernacular Chinese expressions are often ungrammatical or unidiomatic in non-Mandarin dialects. This role may not differ substantially from the role of other lingue franche

, such as Latin

: For those trained in written Chinese, it serves as a common medium; for those untrained in it, the graphic nature of the characters is in general no aid to common understanding (characters such as "one" notwithstanding). In this regard, Chinese characters may be considered a large and inefficient phonetic script. However, Ghil'ad Zuckermann’s exploration of phono-semantic matching

in Standard Chinese

concludes that the Chinese writing system is multifunctional, conveying both semantic and phonetic content.

The variation in vocabulary among dialects has also led to the informal use of "dialectal characters", as well as standard characters that are nevertheless considered archaic by today's standards. Cantonese is unique among non-Mandarin regional languages in having a written colloquial standard, used in Hong Kong and overseas, with a large number of unofficial characters for words particular to this dialect. Written colloquial Cantonese

has become quite popular in online chat rooms and instant messaging, although for formal written communications Cantonese speakers still normally use Vernacular Chinese. To a lesser degree Hokkien

is used in a similar way in Taiwan and elsewhere, although it lacks the level of standardization seen in Cantonese. However, the Ministry of Education of the Republic of China is currently releasing a standard character set for Hokkien, which is to be taught in schools and promoted amongst the general population.

and katakana

.

Chinese characters are called hànzì in Mandarin, after the 漢/汉 Hàn Dynasty

of China; in Japanese, this was pronounced kanji

. In modern written Japanese, kanji are used for nouns, verb stems, and adjective stems, while hiragana are used for prefixes and suffixes; katakana are used exclusively for sound symbols, and for loans from other languages. The Jōyō kanji

, a list of kanji for common use standardized by the Japanese government, contains 2,136 characters—about half the number of characters commanded by literate Chinese.

The role of Chinese characters in Korean and Vietnamese

is much more limited. At one time, many Chinese characters (called hanja

) were introduced into Korean for their meaning, just as in Japanese. Today, written Korean relies almost exclusively on the phonetic hangul

script, in which each syllable is written with two or three phonetic symbols that combine to form a single character. Similarly, the use of Chinese and Chinese-styled characters in the Vietnamese chữ nôm script has been almost entirely superseded by the quốc ngữ alphabet.

Chinese characters are also used within China to write non-Han languages. The largest non-Han people group in China, the Zhuang, have for over 1300 years used Chinese characters. Despite both the introduction of an official alphabetical script in 1957 and the absence of standardization, more Zhuang people can read the Zhuang logograms than the alphabetical script.

, in the introduction to his Advanced Chinese Reader, estimates that a typical Chinese college graduate recognizes 4,000 to 5,000 characters, and 40,000 to 60,000 words. Jerry Norman, in Chinese, places the number of characters somewhat lower, at 3,000 to 4,000. These counts are complicated by the tangled development of Chinese characters. In many cases, a single character came to be written in multiple ways

, in much the same way that English words are sometimes spelled differently in different regions (e.g., "color/colour"). This development was stemmed to an extent by the standardization of the seal script during the Qin dynasty, but soon started again. Although the Shuowen Jiezi lists 10,516 characters—9,353 of them unique (some of which may already have been out of use by the time it was compiled) plus 1,163 graphic variants—the 集韻/集韵 Jíyùn

of the Northern 宋 Sòng Dynasty

, compiled less than a thousand years later in 1039, contains 53,525 characters, most of them graphic variants.

A traditional mechanism is the method of radicals, which uses a set of character roots. These roots, or radicals, generally but imperfectly align with the parts used to compose characters by means of logical aggregation and phonetic complex. A canonical set of 214 radicals was developed during the rule of the 康熙 Kāngxī emperor

(around the year 1700); these are sometimes called the Kangxi radicals. The radicals are ordered first by stroke count (that is, the number of strokes required to write the radical); within a given stroke count, the radicals also have a prescribed order.

Every Chinese character falls under the heading of exactly one of these 214 radicals. In many cases, the radicals are themselves characters, which naturally come first under their own heading. All other characters under a given radical are ordered by the stroke count of the character. Usually, however, there are still many characters with a given stroke count under a given radical. At this point, characters are not given in any recognizable order; the user must locate the character by going through all the characters with that stroke count, typically listed for convenience at the top of the page on which they occur.

Because the method of radicals is applied only to the written character, one need not know how to pronounce a character before looking it up; the entry, once located, usually gives the pronunciation. However, it is not always easy to identify which of the various roots of a character is the proper radical. Accordingly, dictionaries often include a list of hard to locate characters, indexed by total stroke count, near the beginning of the dictionary. Some dictionaries include almost one-seventh of all characters in this list.

Other methods of organization exist, often in an attempt to address the shortcomings of the radical method, but are less common. For instance, it is common for a dictionary ordered principally by the Kangxi radicals to have an auxiliary index by pronunciation, expressed typically in either 漢語拼音/汉语拼音 hànyǔ pīnyīn

or 注音符號/注音符号 zhùyīn fúhào. This index points to the page in the main dictionary where the desired character can be found. Other methods use only the structure of the characters, such as the four-corner method, in which characters are indexed according to the kinds of strokes located nearest the four corners (hence the name of the method), or the 倉頡/仓颉 Cāngjié method

, in which characters are broken down into a set of 24 basic components. Neither the four-corner method nor the Cangjie method requires the user to identify the proper radical, although many strokes or components have alternate forms, which must be memorized in order to use these methods effectively.

The availability of computerized Chinese dictionaries now makes it possible to look characters up directly, without searching, thereby sidestepping the need to index characters for this purpose.

By 1958, however, priority was given officially to simplified Chinese; a phonetic script, hanyu pinyin, had been developed, but its deployment to the exclusion of simplified characters was pushed off to some distant future date. The association between pinyin and Mandarin, as opposed to other dialects, may have contributed to this deferment. It seems unlikely that pinyin will supplant Chinese characters anytime soon as the sole means of representing Chinese.

Pinyin uses the Latin alphabet, along with a few diacritical marks, to represent the sounds of Mandarin in standard pronunciation. For the most part, pinyin uses vowel and consonant letters as they are used in Romance languages (and also in IPA). However, although 'b' and 'p', for instance, represent the voice/unvoiced distinction in some languages, such as French

, they represent the unaspirated/aspirated

distinction in Mandarin; Mandarin has few voiced consonants. Also, the pinyin spellings for a few consonant sounds are markedly different from their spellings in other languages that use the Latin alphabet; for instance, pinyin 'q' and 'x' sound similar to English 'ch' and 'sh', respectively. Pinyin is not the sole transliteration scheme for Mandarin—there are also, for instance, the zhuyin fuhao, Wade-Giles

, and Gwoyeu Romatzyh

systems—but it is dominant in the Chinese-speaking world. All transliterations in this article use the pinyin system.

Chinese language

The Chinese language is a language or language family consisting of varieties which are mutually intelligible to varying degrees. Originally the indigenous languages spoken by the Han Chinese in China, it forms one of the branches of Sino-Tibetan family of languages...

, and the rules about how they are arranged and punctuated. Chinese characters do not constitute an alphabet or a compact syllabary

Syllabary

A syllabary is a set of written symbols that represent syllables, which make up words. In a syllabary, there is no systematic similarity between the symbols which represent syllables with the same consonant or vowel...

. Rather, the writing system is roughly logosyllabic; that is, a character generally represents one syllable

Syllable

A syllable is a unit of organization for a sequence of speech sounds. For example, the word water is composed of two syllables: wa and ter. A syllable is typically made up of a syllable nucleus with optional initial and final margins .Syllables are often considered the phonological "building...

of spoken Chinese and may be a word on its own or a part of a polysyllabic word. The characters themselves are often composed of parts that may represent physical objects, abstract notions, or pronunciation.

Various current Chinese characters have been traced back to the late 商 Shāng Dynasty

Shang Dynasty

The Shang Dynasty or Yin Dynasty was, according to traditional sources, the second Chinese dynasty, after the Xia. They ruled in the northeastern regions of the area known as "China proper" in the Yellow River valley...

about 1200–1050 BCE, but the process of creating characters is thought to have begun some centuries earlier. After a period of variation and evolution, Chinese characters were standardized under the 秦 Qín dynasty

Qin Dynasty

The Qin Dynasty was the first imperial dynasty of China, lasting from 221 to 207 BC. The Qin state derived its name from its heartland of Qin, in modern-day Shaanxi. The strength of the Qin state was greatly increased by the legalist reforms of Shang Yang in the 4th century BC, during the Warring...

(221–206 BCE). Over the millennia, these characters have evolved into well-developed styles of Chinese calligraphy.

Some Chinese characters have been adopted as part of the writing systems of other East Asian languages, such as Japanese

Japanese language

is a language spoken by over 130 million people in Japan and in Japanese emigrant communities. It is a member of the Japonic language family, which has a number of proposed relationships with other languages, none of which has gained wide acceptance among historical linguists .Japanese is an...

and Korean

Korean language

Korean is the official language of the country Korea, in both South and North. It is also one of the two official languages in the Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture in People's Republic of China. There are about 78 million Korean speakers worldwide. In the 15th century, a national writing...

. Literacy requires the memorization of a great many characters: Educated Chinese know about 4,000; educated Japanese know about half that many. The large number of Chinese characters has in part led to the adoption of Western alphabets as an auxiliary means of representing Chinese.

The common belief that all Chinese varieties are mutually comprehensible when written is false. Although Chinese speakers in disparate dialect groups are able to communicate through writing, this is largely due to the fact non-Mandarin speakers write in Mandarin or in a heavily Mandarin-influenced form, rather than in a form that faithfully represents their spoken language. , and its written form

Written Cantonese

Cantonese has the most well-developed written form of all Chinese varieties apart from the standard varieties of Mandarin and Classical Chinese. Standard written Chinese is based on Mandarin, but when spoken word for word as Cantonese, it sounds unnatural because its expressions are ungrammatical...

is quite different from written Mandarin. Characters are chosen to represent Cantonese words based on etymology, and may differ greatly in their meaning as compared to modern Mandarin. In addition, many Cantonese characters are archaic in a Mandarin context, and hundreds (perhaps thousands) of new characters have been created specifically to represent Cantonese-only words (e.g. borrowed words and grammatical particles).

Structure

Written Chinese is not based on an alphabet or a compact syllabary. Instead, Chinese characters are glyphs whose components may depict objects or represent abstract notions. Occasionally a character consists of only one component; more commonly two or more components are combined to form more complex characters, using a variety of different principles. The best known exposition of Chinese character composition is the 說文解字/说文解字 Shuōwén Jiězì

Shuowen Jiezi

The Shuōwén Jiězì was an early 2nd century CE Chinese dictionary from the Han Dynasty. Although not the first comprehensive Chinese character dictionary , it was still the first to analyze the structure of the characters and to give the rationale behind them , as well as the first to use the...

, compiled by 許慎/许慎 Xǔ Shèn

Xu Shen

Xǔ Shèn was a Chinese philologist of the Han Dynasty. He was the author of Shuowen Jiezi, the first Chinese dictionary with character analysis, as well as the first to organize the characters by shared components. It contains over 9,000 character entries under 540 radicals, explaining the origins...

around 120 CE. Since Xu Shen did not have access to Chinese characters in their earliest forms, his analysis cannot always be taken as authoritative. Nonetheless, no later work has supplanted the Shuowen Jiezi in terms of breadth, and it is still relevant to etymological research today.

According to the Shuowen Jiezi, Chinese characters are developed on six basic principles. (These principles, though popularized by the Shuowen Jiezi, were developed earlier; the oldest known mention of them is in the 周禮/周礼 Zhōulǐ—literally, Rites of Zhou—a text from about 150 BCE.) The first two principles produce simple characters, known as 文 wén:

- 象形 xiàngxíng: Pictographs, in which the character is a graphical depiction of the object it denotes. Examples: 人 rén "person", 日 rì "sun", 木 mù "tree/wood".

- 指事 zhǐshì: Indicatives, or ideographs, in which the character represents an abstract notion. Examples: 上 shàng "up", 下 xià "down", 三 sān "three".

The remaining four principles produce complex characters historically called 字 zì (although this term is now generally used to refer to all characters, whether simple or complex). Of these four, two construct characters from simpler parts:

- 會意/会意 huìyì: Logical aggregates, in which two or more parts are used for their meaning. This yields a composite meaning, which is then applied to the new character. Example: 東/东 dōng "east", which represents a sun rising in the trees.

- 形聲/形声 xíngshēng: Phonetic complexes, in which one part—often called the radicalRadical (Chinese character)A Chinese radical is a component of a Chinese character. The term may variously refer to the original semantic element of a character, or to any semantic element, or, loosely, to any element whatever its origin or purpose...

—indicates the general semantic category of the character (such as water-related or eye-related), and the other part is another character, used for its phonetic value. Example: 晴 qíng "clear/fair (weather)", which is composed of 日 rì "sun", and 青 qīng "blue/green", which is used for its pronunciation.

In contrast to the popular conception of Chinese as a primarily pictographic or ideographic language, the vast majority of Chinese characters (about 95 percent of the characters in the Shuowen Jiezi) are constructed as either logical aggregates or, more often, phonetic complexes. In fact, some phonetic complexes were originally simple pictographs that were later augmented by the addition of a semantic root. An example is 炷 zhù "candle" (now archaic, meaning "lampwick"), which was originally a pictograph 主, a character that is now pronounced zhǔ and means "host". The character 火 huǒ "fire" was added to indicate that the meaning is fire-related.

The last two principles do not produce new written forms; instead, they transfer new meanings to existing forms:

- 轉注/转注 zhuǎnzhù: Transference, in which a character, often with a simple, concrete meaning takes on an extended, more abstract meaning. Example: 網/网 wǎng "net", which was originally a pictograph depicting a fishing net. Over time, it has taken on an extended meaning, covering any kind of lattice; for instance, it can be used to refer to a computer network.

- 假借 jiǎjiè: Borrowing, in which a character is used, either intentionally or accidentally, for some entirely different purpose. Example: 哥 gē "older brother", which is written with a character originally meaning "song/sing", now written 歌 gē. Once, there was no character for "older brother", so an otherwise unrelated character with the right pronunciation was borrowed for that meaning.

Chinese characters are written to fit into a square, even when composed of two simpler forms written side-by-side or top-to-bottom. In such cases, each form is compressed to fit the entire character into a square.

Strokes

Character components can be further subdivided into strokes. The strokes of Chinese characters fall into eight main categories: horizontal (一), vertical (丨), left-falling (丿), right-falling (丶), rising, dot (、), hook (亅), and turning (乛, 乚, 乙, etc.).There are eight basic rules of stroke order in writing a Chinese character:

- Horizontal strokes are written before vertical ones.

- Left-falling strokes are written before right-falling ones.

- Characters are written from top to bottom.

- Characters are written from left to right.

- If a character is framed from above, the frame is written first.

- If a character is framed from below, the frame is written last.

- Frames are closed last.

- In a symmetrical character, the middle is drawn first, then the sides.

These rules do not strictly apply to every situation and are occasionally violated.

Layout

In modern times, the familiar Western layout of horizontal rows from left to right, read from the top of the page to the bottom, has become more popular, especially in the People's Republic of China

People's Republic of China

China , officially the People's Republic of China , is the most populous country in the world, with over 1.3 billion citizens. Located in East Asia, the country covers approximately 9.6 million square kilometres...

(mainland China), where the government mandated left-to-right writing in 1955. The Republic of China

Republic of China

The Republic of China , commonly known as Taiwan , is a unitary sovereign state located in East Asia. Originally based in mainland China, the Republic of China currently governs the island of Taiwan , which forms over 99% of its current territory, as well as Penghu, Kinmen, Matsu and other minor...

(Taiwan

Taiwan

Taiwan , also known, especially in the past, as Formosa , is the largest island of the same-named island group of East Asia in the western Pacific Ocean and located off the southeastern coast of mainland China. The island forms over 99% of the current territory of the Republic of China following...

) followed suit in 2004. The use of punctuation has also become more common, whether the text is written in columns or rows. The punctuation marks are clearly influenced by their Western counterparts, although some marks are particular to Asian languages: for example, the double and single quotation marks (『 』 and 「 」); the hollow period (。), which is otherwise used just like an ordinary period; and a special kind of comma called an enumeration comma (、), which is used to separate items in a list, as opposed to clauses in a sentence.

Signs

Signage

Signage is any kind of visual graphics created to display information to a particular audience. This is typically manifested in the form of wayfinding information in places such as streets or inside/outside of buildings.-History:...

are a particularly challenging aspect of written Chinese layout, since they can be written either left to right or right to left (the latter can be thought of as the traditional layout with each "column" being one character high), as well as from top to bottom. It is not uncommon to encounter all three orientations on signs on neighboring stores.

Evolution

Chinese is one of the oldest continually used writing systems still in use. In 2003, tentative evidence was found at 賈湖/贾湖 JiǎhúJiahu

Jiahu was the site of a Neolithic Yellow River settlement based in the central plains of ancient China, modern Wuyang, Henan Province. Archaeologists consider the site to be one of the earliest examples of the Peiligang culture. Settled from 7000 to 5800 BC, the site was later flooded and abandoned...

, an archaeological site in the 河南 Hénán

Henan

Henan , is a province of the People's Republic of China, located in the central part of the country. Its one-character abbreviation is "豫" , named after Yuzhou , a Han Dynasty state that included parts of Henan...

province of China, for an early form of Chinese writing. Some symbols were found that bear striking resemblance to certain modern characters, such as 目 mù "eye". Since the Jiahu site dates from about 6600 BCE, it predates the earliest confirmed Chinese writing by about 4,000 years. The nature of this finding—whether it represents true writing (that is, a general mechanism for expression) or simply proto-writing (which comprises a limited set of symbols)—is still controversial. Critics contend that if the Jiahu finding really represented a direct ancestor of modern Chinese writing, it would indicate that Chinese writing remained relatively static for three millennia, at a time when China was sparsely populated.

Shang Dynasty

The Shang Dynasty or Yin Dynasty was, according to traditional sources, the second Chinese dynasty, after the Xia. They ruled in the northeastern regions of the area known as "China proper" in the Yellow River valley...

in the latter half of the second millennium BCE, were found on oracle bones, primarily ox scapulae and turtle shells, originally used for divination. Characters were inscribed on the bones in order to frame a question; the bones were then heated over a fire and the resulting cracks were interpreted to determine the answer. Such characters are called 甲骨文 jiǎgǔwén "shell-bone script" or oracle bone script

Oracle bone script

Oracle bone script refers to incised ancient Chinese characters found on oracle bones, which are animal bones or turtle shells used in divination in Bronze Age China...

.

Zhou Dynasty

The Zhou Dynasty was a Chinese dynasty that followed the Shang Dynasty and preceded the Qin Dynasty. Although the Zhou Dynasty lasted longer than any other dynasty in Chinese history, the actual political and military control of China by the Ji family lasted only until 771 BC, a period known as...

(c 1066–770 BCE) and the Spring and Autumn Period (770–476 BCE), a kind of writing called 金文 jīnwén "metal script". Jinwen characters are less angular and angularized than the oracle bone script. Later, in the Warring States Period

Warring States Period

The Warring States Period , also known as the Era of Warring States, or the Warring Kingdoms period, covers the Iron Age period from about 475 BC to the reunification of China under the Qin Dynasty in 221 BC...

(475–221 BCE), the script became still more regular, and settled on a form, called 六國文字/六国文字 liùguó wénzì "script of the six states", that Xu Shen used as source material in the Shuowen Jiezi. These characters were later embellished and stylized to yield the 篆書/篆书 zhuànshū seal script

Seal script

Seal script is an ancient style of Chinese calligraphy. It evolved organically out of the Zhōu dynasty script , arising in the Warring State of Qin...

, which represents the oldest form of Chinese characters still in modern use. They are used principally for signature seals, or chops

Seal (Chinese)

A seal, in an East Asian context, is a general name for printing stamps and impressions thereof that are used in lieu of signatures in personal documents, office paperwork, contracts, art, or any item requiring acknowledgment or authorship...

, which are often used in place of a signature for Chinese documents and artwork. 李斯 Lǐ Sī

Li Si

Li Si was the influential Prime Minister of the feudal state and later of the dynasty of Qin, between 246 BC and 208 BC. A famous Legalist, he was also a notable calligrapher. Li Si served under two rulers: Qin Shi Huang, king of Qin and later First Emperor of China—and his son, Qin Er Shi...

promulgated the seal script as the standard throughout the empire during the Qin dynasty

Qin Dynasty

The Qin Dynasty was the first imperial dynasty of China, lasting from 221 to 207 BC. The Qin state derived its name from its heartland of Qin, in modern-day Shaanxi. The strength of the Qin state was greatly increased by the legalist reforms of Shang Yang in the 4th century BC, during the Warring...

, then newly unified.

Seal script in turn evolved into the other surviving writing styles; the first writing style to follow was the clerical script. The development of such a style can be attributed to those of the Qin Dynasty who were seeking to create a convenient form of written characters for daily usage. In general, clerical script characters are "flat" in appearance, being wider than the seal script, which tends to be taller than it is wide. Compared with the seal script, clerical script characters are strikingly rectilinear. In running script (行書/行书 xíngshū), a semi-cursive form, the character elements begin to run into each other, although the characters themselves generally remain separate.

Running script eventually evolved into grass script (草書/草书 cǎoshū), a fully cursive form, in which the characters are often entirely unrecognizable by their canonical forms. Grass script gives the impression of anarchy in its appearance, and there is indeed considerable freedom on the part of the calligrapher, but this freedom is circumscribed by conventional "abbreviations" in the forms of the characters. Regular script

Regular script

Regular script , also called 正楷 , 真書 , 楷体 and 正書 , is the newest of the Chinese script styles Regular script , also called 正楷 , 真書 (zhēnshū), 楷体 (kǎitǐ) and 正書 (zhèngshū), is the newest of the Chinese script styles Regular script , also called 正楷 , 真書 (zhēnshū), 楷体 (kǎitǐ) and 正書 (zhèngshū), is...

(楷書/楷书 kǎishū), a non-cursive form, is the most widely recognized script. In regular script, each stroke of each character is clearly drawn out from the others. Even though both the running and grass scripts appear to be derived as semi-cursive and cursive variants of regular script, it is in fact the regular script that was the last to develop.

|

|

|

|

|

Regular script is considered the archetype for Chinese writing, and forms the basis for most printed forms. In addition, regular script imposes a stroke order, which must be followed in order for the characters to be written correctly. (Strictly speaking, this stroke order applies to the clerical, running, and grass scripts as well, but especially in the running and grass scripts, this order is occasionally deviated from.) Thus, for instance, the character 木 mù "wood" must be written starting with the horizontal stroke, drawn from left to right; next, the vertical stroke, from top to bottom, with a small hook toward the upper left at the end; next, the left diagonal stroke, from top to bottom; and lastly the right diagonal stroke, from top to bottom.

Simplified and traditional Chinese

In the 20th century, written Chinese divided into two canonical forms, called 簡體字/简体字 jiǎntǐzì (simplified Chinese) and 繁體字/繁体字 fántǐzì (traditional Chinese). Simplified Chinese was developed in mainland China in order to make the characters faster to write (especially as some characters had as many as a few dozen strokes) and easier to memorize. The People's Republic of China claims that both goals have been achieved, but some external observers disagree. Little systematic study has been conducted on how simplified Chinese has affected the way Chinese people become literate; the only studies conducted before it was standardized in mainland China seem to have been statistical ones regarding how many strokes were saved on average in samples of running text.The simplified forms have also been criticized for being inconsistent. For instance, traditional 讓 ràng "allow" is simplified to 让, in which the phonetic on the right side is reduced from 17 strokes to just three. (The speech radical on the left has also been simplified.) However, the same phonetic is used in its full form, even in simplified Chinese, in such characters as 壤 rǎng "soil" and 齉 nàng "snuffle"; these forms remained uncontracted because they were relatively uncommon and would therefore represent a negligible stroke reduction. On the other hand, some simplified forms are simply calligraphic abbreviations of long standing, as for example 万 wàn "ten thousand

Myriad

Myriad , "numberlesscountless, infinite", is a classical Greek word for the number 10,000. In modern English, the word refers to an unspecified large quantity.-History and usage:...

", for which the traditional Chinese form is 萬.

Simplified Chinese is standard in the People's Republic of China, Singapore

Singapore

Singapore , officially the Republic of Singapore, is a Southeast Asian city-state off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, north of the equator. An island country made up of 63 islands, it is separated from Malaysia by the Straits of Johor to its north and from Indonesia's Riau Islands by the...

, and Malaysia. Traditional Chinese is retained in Hong Kong

Hong Kong

Hong Kong is one of two Special Administrative Regions of the People's Republic of China , the other being Macau. A city-state situated on China's south coast and enclosed by the Pearl River Delta and South China Sea, it is renowned for its expansive skyline and deep natural harbour...

, Taiwan, Macau

Macau

Macau , also spelled Macao , is, along with Hong Kong, one of the two special administrative regions of the People's Republic of China...

and overseas Chinese

Overseas Chinese

Overseas Chinese are people of Chinese birth or descent who live outside the Greater China Area . People of partial Chinese ancestry living outside the Greater China Area may also consider themselves Overseas Chinese....

communities (except Singapore

Singapore

Singapore , officially the Republic of Singapore, is a Southeast Asian city-state off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, north of the equator. An island country made up of 63 islands, it is separated from Malaysia by the Straits of Johor to its north and from Indonesia's Riau Islands by the...

and Malaysia). Throughout this article, Chinese text is given in both simplified and traditional forms when they differ, with the traditional forms being given first.

Function

For over two thousand years, the prevailing written standard was a vocabulary and syntax rooted in Chinese as spoken around the time of Confucius

Confucius

Confucius , literally "Master Kong", was a Chinese thinker and social philosopher of the Spring and Autumn Period....

(about 500 BCE), called Classical Chinese

Classical Chinese

Classical Chinese or Literary Chinese is a traditional style of written Chinese based on the grammar and vocabulary of ancient Chinese, making it different from any modern spoken form of Chinese...

, or 文言文 wényánwén. Over the centuries, Classical Chinese gradually acquired some of its grammar and character senses from the various dialects. This accretion was generally slow and minor; however, by the 20th century, Classical Chinese was distinctly different from any contemporary dialect, and had to be learned separately. Once learned, it was a common medium for communication between people speaking different dialects, many of which were mutually unintelligible by the end of the first millennium CE. A Mandarin speaker might say yī, a Cantonese

Standard Cantonese

Cantonese, or Standard Cantonese, is a language that originated in the vicinity of Canton in southern China, and is often regarded as the prestige dialect of Yue Chinese....

jat1, and a Hokkienese tsit, but all three will understand the character 一 "one".

Chinese dialects vary not only by pronunciation, but also, to a lesser extent, vocabulary and grammar. Modern written Chinese, which replaced Classical Chinese as the written standard as an indirect result of the May Fourth Movement

May Fourth Movement

The May Fourth Movement was an anti-imperialist, cultural, and political movement growing out of student demonstrations in Beijing on May 4, 1919, protesting the Chinese government's weak response to the Treaty of Versailles, especially the Shandong Problem...

of 1919, is not technically bound to any single dialect; however, it most nearly represents the vocabulary and syntax of Mandarin, by far the most widespread Chinese dialect in terms of both geographical area and number of speakers. This version of written Chinese is called Vernacular Chinese

Vernacular Chinese

Written Vernacular Chinese refers to forms of written Chinese based on the vernacular language, in contrast to Classical Chinese, the written standard used from the Spring and Autumn Period to the early twentieth century...

, or 白話/白话 báihuà (literally, "plain speech"). Despite its ties to the dominant Mandarin dialect, Vernacular Chinese also permits some communication between people of different dialects, limited by the fact that Vernacular Chinese expressions are often ungrammatical or unidiomatic in non-Mandarin dialects. This role may not differ substantially from the role of other lingue franche

Lingua franca

A lingua franca is a language systematically used to make communication possible between people not sharing a mother tongue, in particular when it is a third language, distinct from both mother tongues.-Characteristics:"Lingua franca" is a functionally defined term, independent of the linguistic...

, such as Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

: For those trained in written Chinese, it serves as a common medium; for those untrained in it, the graphic nature of the characters is in general no aid to common understanding (characters such as "one" notwithstanding). In this regard, Chinese characters may be considered a large and inefficient phonetic script. However, Ghil'ad Zuckermann’s exploration of phono-semantic matching

Phono-semantic matching

Phono-semantic matching is a linguistic term referring to camouflaged borrowing in which a foreign word is matched with a phonetically and semantically similar pre-existent native word/root....

in Standard Chinese

Standard Chinese

Standard Chinese, or Modern Standard Chinese, also known as Mandarin or Putonghua, is the official language of the People's Republic of China and Republic of China , and is one of the four official languages of Singapore....

concludes that the Chinese writing system is multifunctional, conveying both semantic and phonetic content.

The variation in vocabulary among dialects has also led to the informal use of "dialectal characters", as well as standard characters that are nevertheless considered archaic by today's standards. Cantonese is unique among non-Mandarin regional languages in having a written colloquial standard, used in Hong Kong and overseas, with a large number of unofficial characters for words particular to this dialect. Written colloquial Cantonese

Written Cantonese

Cantonese has the most well-developed written form of all Chinese varieties apart from the standard varieties of Mandarin and Classical Chinese. Standard written Chinese is based on Mandarin, but when spoken word for word as Cantonese, it sounds unnatural because its expressions are ungrammatical...

has become quite popular in online chat rooms and instant messaging, although for formal written communications Cantonese speakers still normally use Vernacular Chinese. To a lesser degree Hokkien

Hokkien

Hokkien is a Hokkien word corresponding to Standard Chinese "Fujian". It may refer to:* Hokkien dialect, a dialect of Min Nan Chinese spoken in Southern Fujian , Taiwan, South-east Asia, and elsewhere....

is used in a similar way in Taiwan and elsewhere, although it lacks the level of standardization seen in Cantonese. However, the Ministry of Education of the Republic of China is currently releasing a standard character set for Hokkien, which is to be taught in schools and promoted amongst the general population.

Other languages

Chinese characters were first introduced into Japanese sometime in the first half of the first millennium CE, probably from Chinese products imported into Japan through Korea. At the time, Japanese had no native written system, and Chinese characters were used for the most part to represent Japanese words with the corresponding meanings, rather than similar pronunciations. A notable exception to this rule was the system of man'yōgana, which used a small set of Chinese characters to help indicate pronunciation. The man'yōgana later developed into the phonetic syllabaries, hiraganaHiragana

is a Japanese syllabary, one basic component of the Japanese writing system, along with katakana, kanji, and the Latin alphabet . Hiragana and katakana are both kana systems, in which each character represents one mora...

and katakana

Katakana

is a Japanese syllabary, one component of the Japanese writing system along with hiragana, kanji, and in some cases the Latin alphabet . The word katakana means "fragmentary kana", as the katakana scripts are derived from components of more complex kanji. Each kana represents one mora...

.

Chinese characters are called hànzì in Mandarin, after the 漢/汉 Hàn Dynasty

Han Dynasty

The Han Dynasty was the second imperial dynasty of China, preceded by the Qin Dynasty and succeeded by the Three Kingdoms . It was founded by the rebel leader Liu Bang, known posthumously as Emperor Gaozu of Han. It was briefly interrupted by the Xin Dynasty of the former regent Wang Mang...

of China; in Japanese, this was pronounced kanji

Kanji

Kanji are the adopted logographic Chinese characters hanzi that are used in the modern Japanese writing system along with hiragana , katakana , Indo Arabic numerals, and the occasional use of the Latin alphabet...

. In modern written Japanese, kanji are used for nouns, verb stems, and adjective stems, while hiragana are used for prefixes and suffixes; katakana are used exclusively for sound symbols, and for loans from other languages. The Jōyō kanji

Joyo kanji

The is the guide to kanji characters announced officially by the Japanese Ministry of Education. Current jōyō kanji are those on a list of 2,136 characters issued in 2010...

, a list of kanji for common use standardized by the Japanese government, contains 2,136 characters—about half the number of characters commanded by literate Chinese.

The role of Chinese characters in Korean and Vietnamese

Vietnamese language

Vietnamese is the national and official language of Vietnam. It is the mother tongue of 86% of Vietnam's population, and of about three million overseas Vietnamese. It is also spoken as a second language by many ethnic minorities of Vietnam...

is much more limited. At one time, many Chinese characters (called hanja

Hanja

Hanja is the Korean name for the Chinese characters hanzi. More specifically, it refers to those Chinese characters borrowed from Chinese and incorporated into the Korean language with Korean pronunciation...

) were introduced into Korean for their meaning, just as in Japanese. Today, written Korean relies almost exclusively on the phonetic hangul

Hangul

Hangul,Pronounced or ; Korean: 한글 Hangeul/Han'gŭl or 조선글 Chosŏn'gŭl/Joseongeul the Korean alphabet, is the native alphabet of the Korean language. It is a separate script from Hanja, the logographic Chinese characters which are also sometimes used to write Korean...

script, in which each syllable is written with two or three phonetic symbols that combine to form a single character. Similarly, the use of Chinese and Chinese-styled characters in the Vietnamese chữ nôm script has been almost entirely superseded by the quốc ngữ alphabet.

Chinese characters are also used within China to write non-Han languages. The largest non-Han people group in China, the Zhuang, have for over 1300 years used Chinese characters. Despite both the introduction of an official alphabetical script in 1957 and the absence of standardization, more Zhuang people can read the Zhuang logograms than the alphabetical script.

Literacy

Because the majority of modern Chinese words contain more than one character, there are at least two measuring sticks for Chinese literacy: the number of characters known, and the number of words known. John DeFrancisJohn DeFrancis

John DeFrancis was an American linguist, sinologist, author of Chinese language textbooks, lexicographer of Chinese dictionaries, and Professor Emeritus of Chinese Studies at the University of Hawaii at Mānoa....

, in the introduction to his Advanced Chinese Reader, estimates that a typical Chinese college graduate recognizes 4,000 to 5,000 characters, and 40,000 to 60,000 words. Jerry Norman, in Chinese, places the number of characters somewhat lower, at 3,000 to 4,000. These counts are complicated by the tangled development of Chinese characters. In many cases, a single character came to be written in multiple ways

Variant Chinese character

Variant Chinese characters are Chinese characters that are homophones and synonyms. Almost all variants are allographs in most circumstances, such as casual handwriting...

, in much the same way that English words are sometimes spelled differently in different regions (e.g., "color/colour"). This development was stemmed to an extent by the standardization of the seal script during the Qin dynasty, but soon started again. Although the Shuowen Jiezi lists 10,516 characters—9,353 of them unique (some of which may already have been out of use by the time it was compiled) plus 1,163 graphic variants—the 集韻/集韵 Jíyùn

Jiyun

The Jiyun is a Chinese rime dictionary published in 1037 during the Song Dynasty. The chief editor Ding Du and others expanded and revised the Guangyun. It is possible, according to Teng and Biggerstaff , that Sima Guang completed the text in 1067...

of the Northern 宋 Sòng Dynasty

Song Dynasty

The Song Dynasty was a ruling dynasty in China between 960 and 1279; it succeeded the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms Period, and was followed by the Yuan Dynasty. It was the first government in world history to issue banknotes or paper money, and the first Chinese government to establish a...

, compiled less than a thousand years later in 1039, contains 53,525 characters, most of them graphic variants.

Dictionaries

Chinese is not based on an alphabet or syllabary, so Chinese dictionaries, as well as dictionaries that define Chinese characters in other languages, cannot easily be alphabetized or otherwise lexically ordered, as English dictionaries are. The need to arrange Chinese characters in order to permit efficient lookup has given rise to a considerable variety of ways to organize and index the characters.A traditional mechanism is the method of radicals, which uses a set of character roots. These roots, or radicals, generally but imperfectly align with the parts used to compose characters by means of logical aggregation and phonetic complex. A canonical set of 214 radicals was developed during the rule of the 康熙 Kāngxī emperor

Kangxi Emperor

The Kangxi Emperor ; Manchu: elhe taifin hūwangdi ; Mongolian: Энх-Амгалан хаан, 4 May 1654 –20 December 1722) was the fourth emperor of the Qing Dynasty, the first to be born on Chinese soil south of the Pass and the second Qing emperor to rule over China proper, from 1661 to 1722.Kangxi's...

(around the year 1700); these are sometimes called the Kangxi radicals. The radicals are ordered first by stroke count (that is, the number of strokes required to write the radical); within a given stroke count, the radicals also have a prescribed order.

Every Chinese character falls under the heading of exactly one of these 214 radicals. In many cases, the radicals are themselves characters, which naturally come first under their own heading. All other characters under a given radical are ordered by the stroke count of the character. Usually, however, there are still many characters with a given stroke count under a given radical. At this point, characters are not given in any recognizable order; the user must locate the character by going through all the characters with that stroke count, typically listed for convenience at the top of the page on which they occur.

Because the method of radicals is applied only to the written character, one need not know how to pronounce a character before looking it up; the entry, once located, usually gives the pronunciation. However, it is not always easy to identify which of the various roots of a character is the proper radical. Accordingly, dictionaries often include a list of hard to locate characters, indexed by total stroke count, near the beginning of the dictionary. Some dictionaries include almost one-seventh of all characters in this list.

Other methods of organization exist, often in an attempt to address the shortcomings of the radical method, but are less common. For instance, it is common for a dictionary ordered principally by the Kangxi radicals to have an auxiliary index by pronunciation, expressed typically in either 漢語拼音/汉语拼音 hànyǔ pīnyīn

Pinyin

Pinyin is the official system to transcribe Chinese characters into the Roman alphabet in China, Malaysia, Singapore and Taiwan. It is also often used to teach Mandarin Chinese and spell Chinese names in foreign publications and used as an input method to enter Chinese characters into...

or 注音符號/注音符号 zhùyīn fúhào. This index points to the page in the main dictionary where the desired character can be found. Other methods use only the structure of the characters, such as the four-corner method, in which characters are indexed according to the kinds of strokes located nearest the four corners (hence the name of the method), or the 倉頡/仓颉 Cāngjié method

Cangjie method

The Cangjie input method is a system by which Chinese characters may be entered into a computer by means of a standard keyboard...

, in which characters are broken down into a set of 24 basic components. Neither the four-corner method nor the Cangjie method requires the user to identify the proper radical, although many strokes or components have alternate forms, which must be memorized in order to use these methods effectively.

The availability of computerized Chinese dictionaries now makes it possible to look characters up directly, without searching, thereby sidestepping the need to index characters for this purpose.

Transliteration and romanization

Chinese characters do not reliably indicate their pronunciation, even for any single dialect. It is therefore useful to be able to transliterate a dialect of Chinese into the Latin alphabet, and Xiao'erjing for those who cannot read Chinese characters. However, transliteration was not always considered merely a way to record the sounds of any particular dialect of Chinese; it was once also considered a potential replacement for the Chinese characters. This was first prominently proposed during the May Fourth Movement, and it gained further support with the victory of the Communists in 1949. Immediately afterward, the mainland government began two parallel programs relating to written Chinese. One was the development of an alphabetic script for Mandarin, which was spoken by about two-thirds of the Chinese population; the other was the simplification of the traditional characters—a process that would eventually lead to simplified Chinese. The latter was not viewed as an impediment to the former; rather, it would ease the transition toward the exclusive use of an alphabetic (or at least phonetic) script.By 1958, however, priority was given officially to simplified Chinese; a phonetic script, hanyu pinyin, had been developed, but its deployment to the exclusion of simplified characters was pushed off to some distant future date. The association between pinyin and Mandarin, as opposed to other dialects, may have contributed to this deferment. It seems unlikely that pinyin will supplant Chinese characters anytime soon as the sole means of representing Chinese.

Pinyin uses the Latin alphabet, along with a few diacritical marks, to represent the sounds of Mandarin in standard pronunciation. For the most part, pinyin uses vowel and consonant letters as they are used in Romance languages (and also in IPA). However, although 'b' and 'p', for instance, represent the voice/unvoiced distinction in some languages, such as French

French language

French is a Romance language spoken as a first language in France, the Romandy region in Switzerland, Wallonia and Brussels in Belgium, Monaco, the regions of Quebec and Acadia in Canada, and by various communities elsewhere. Second-language speakers of French are distributed throughout many parts...

, they represent the unaspirated/aspirated

Aspiration (phonetics)

In phonetics, aspiration is the strong burst of air that accompanies either the release or, in the case of preaspiration, the closure of some obstruents. To feel or see the difference between aspirated and unaspirated sounds, one can put a hand or a lit candle in front of one's mouth, and say pin ...

distinction in Mandarin; Mandarin has few voiced consonants. Also, the pinyin spellings for a few consonant sounds are markedly different from their spellings in other languages that use the Latin alphabet; for instance, pinyin 'q' and 'x' sound similar to English 'ch' and 'sh', respectively. Pinyin is not the sole transliteration scheme for Mandarin—there are also, for instance, the zhuyin fuhao, Wade-Giles

Wade-Giles

Wade–Giles , sometimes abbreviated Wade, is a romanization system for the Mandarin Chinese language. It developed from a system produced by Thomas Wade during the mid-19th century , and was given completed form with Herbert Giles' Chinese–English dictionary of 1892.Wade–Giles was the most...

, and Gwoyeu Romatzyh

Gwoyeu Romatzyh

Gwoyeu Romatzyh , abbreviated GR, is a system for writing Mandarin Chinese in the Latin alphabet. The system was conceived by Y.R. Chao and developed by a group of linguists including Chao and Lin Yutang from 1925 to 1926. Chao himself later published influential works in linguistics using GR...

systems—but it is dominant in the Chinese-speaking world. All transliterations in this article use the pinyin system.

External links

- Yue E Li and Christopher Upward. "Review of the process of reform in the simplification of Chinese Characters". (Journal of Simplified Spelling Society, 1992/2 pp. 14–16, later designated J13)

- WrittenChinese.Com Free Online Chinese-English Dictionary Dictionary includes written Chinese character stroke orders and animations.