Claud Schuster, 1st Baron Schuster

Encyclopedia

Claud Schuster, 1st Baron Schuster, GCB

, CVO

, KC (22 August 1869 – 28 June 1956) was a British barrister

and civil servant noted for his long tenure as Permanent Secretary to the Lord Chancellor's Office

. Born to a middle-class Mancunian

family, Schuster was educated at St. George's School, Ascot

and Winchester College

before matriculating

at New College, Oxford

in 1888 to study history. After graduation he joined the Inner Temple

with the aim of becoming a barrister, and was called to the Bar

in 1895. Practising in Liverpool, Schuster was not noted as a particularly successful barrister, and he joined Her Majesty's Civil Service in 1899 as secretary to the Chief Commissioner of the Local Government Act Commission.

After serving as secretary to several more commissions, he was made Permanent Secretary to the Lord Chancellor's Office in 1915. Schuster served in this position for 29 years under ten different Lord Chancellors, and with the contacts obtained thanks to his long tenure and his work outside the Office he became "one of the most influential Permanent Secretaries of the 20th century". His influence over decisions within the Lord Chancellor's Office and greater Civil Service led to criticism and suspicions that he was a "power behind the throne", which culminated in a verbal attack by the Lord Chief Justice Lord Hewart

in 1934 during a session of the House of Lords

. Schuster retired in 1944 and was made Baron Schuster, of Cerne, in the County of Dorset. Despite being officially retired he continued to work in government circles, such as with the Allied Commission for Austria and by using his seat in the House of Lords as a way to directly criticise legislation.

Schuster was born on 22 August 1869 to Frederick Schuster, a manager of the Manchester firm of merchants Schuster, Fulder and Company, and his wife Sophia Wood, the daughter of a Lieutenant Colonel in the Indian Army. The family described themselves as "Unitarian

Schuster was born on 22 August 1869 to Frederick Schuster, a manager of the Manchester firm of merchants Schuster, Fulder and Company, and his wife Sophia Wood, the daughter of a Lieutenant Colonel in the Indian Army. The family described themselves as "Unitarian

" but were descended from Jews who had converted to Christianity in the mid-1850s and included other notable people such as Sir Arthur Schuster

, Sir Felix Schuster, and later Sir George Schuster. From the age of seven he was educated at St. George's School, Ascot

, one of the most expensive preparatory schools in the country but one known for harsh treatment; it was standard for the headmaster to flog pupils until they bled and force other students and staff to listen to their screams. During the school holidays he accompanied his father to Switzerland, where he developed a life-long love of mountaineering and skiing. He was president of the Alpine Club

from 1938 to 1940.

When he was fourteen he was sent to Winchester College

, which was known as both the most academic of the main public schools and also for lacking in comfort. Schuster's time at St George's had prepared him for discomfort, however, and he was noted as being very proud of attending the school. While at Winchester Schuster played Winchester College football

and was occasionally involved in debates; he was not, however, noted as a particularly exceptional pupil. He matriculated

at New College, Oxford

in 1888 and graduated with a second-class degree in history in 1892; again he was not noted as a particularly outstanding student, which was attributed to the time he spent enjoying himself rather than studying. Despite his lack of academic brilliance he was invited to present the Romanes Lecture

in 1949, an honour normally only given to the most eminent alumni of Oxford. After graduation he applied to become a Fellow of All Souls College, Oxford

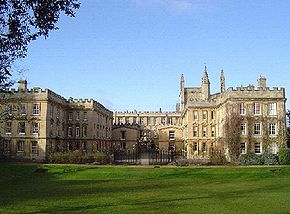

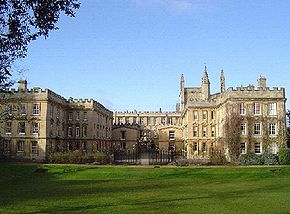

but was rejected.

After his failure to become a Fellow of All Souls, Schuster joined the Inner Temple

After his failure to become a Fellow of All Souls, Schuster joined the Inner Temple

and was called to the bar in 1895. He practised in Liverpool and, though he was not noted as a particularly successful barrister, he became Circuit Junior of the Northern Circuit Bar in late 1895, an important position. By this point Schuster was married and required a steady income to support his family, something which the bar was not providing. With his love of the English language and the knowledge that he was "good with paper" Schuster decided to join Civil Service, with the intention of becoming a Permanent Secretary

.

Schuster entered the Civil Service in 1899 and as a qualified lawyer was exempt from the required examinations, something that marked him as "different" from other civil service employees with whom he worked. His first post was as secretary to the Chief Commissioner of the Local Government Act Commission, which produced a report leading to the creation of the London County Council

. After this he worked as a secretary to the Great Northern Railway

and then for the workers' union at London & Smith's Bank Ltd. After his job at the union he was noticed by Robert Morant

who employed him as a temporary legal assistant to the Board of Education

on the understanding that the job would become permanent, which it did in 1907. In 1911 he was promoted to Principal Assistant Secretary, and after Morant was appointed to the English Commission under the National Insurance Act 1911

Schuster followed him by being appointed Chief Registrar of the Friendly Societies, which granted him a place on the Societies' committee.

In February 1912 he gave up his position as Chief Registrar to become Secretary (and then legal adviser) to the English Insurance Commission, with the newspapers of the time reporting that he had had "three promotions in two months", a consequence of his high standing with Morant. During this period he was also involved in drafting education bills with Arthur Thring. The commission was "a galaxy of future Whitehall stars", and contained many individuals who would later become noted civil servants in their own right, including Morant, Schuster, John Anderson

, Warren Fisher

and John Bradbury. The contacts Schuster made during his time on the committee were instrumental in advancing his career; as a lawyer rather than a dedicated civil servant he was considered an outsider, and the links he made – particularly the friendships he struck up with Fisher and Anderson – helped allay this to some extent.

He was knighted in 1913 for his services on various committees.

, who had served as Permanent Secretary to the Lord Chancellor's Office, was close to retirement. The current Lord Chancellor Lord Haldane

believed that the duties of a Lord Chancellor were too much for one man, and should be divided between a Lord Chancellor and a Minister of Justice. As such he looked for a Permanent Secretary who was a qualified lawyer and who could help him set up a Ministry of Justice after the war, appointing Schuster in early 1915. The two did not work together, however, until Haldane became Lord Chancellor for a second time in 1924; he was forced to resign several months before Schuster started work on 2 July 1915 after being accused of pro-German sympathies.

, who was appointed on 27 May 1915. Although most senior government offices at this time were held by wealthy aristocrats, the office of Lord Chancellor stood out as most of the appointees were lawyers from the middle class. Buckmaster was considered "the most plebeian

of Lord Chancellors", as he was the son of a farmer and schoolteacher who later became a Justice of the Peace

. Schuster became Permanent Secretary in July, a month after Buckmaster took his post, and immediately tried to make an impression on the workings of the office by modernising it; under the previous Permanent Secretary – who abhorred time-saving mechanisms – shorthand had been forbidden, and the office had owned only one typewriter. Buckmaster and Schuster had similar outlooks on World War I

, with both their sons serving on the Western Front

; Schuster almost certainly helped write the 1915 memorandum Buckmaster circulated to the Westminster Cabinet

arguing that forces should be concentrated on the Western Front rather than spread out in an attempt to assault other areas.

H. H. Asquith

resigned as Prime Minister in December 1916, and as a member of Asquith's cabinet Buckmaster followed him. He was replaced by Lord Finlay

who was appointed on 12 December. Aged 74 when he was appointed, Finlay was the oldest person to be made Lord Chancellor other than Lord Campbell

, who was 80 when he was appointed in 1859, and his age showed, with his decisions being slow and cautious. Luckily the job of the Lord Chancellor during the last two years of World War I was limited to maintaining the system rather than instituting any changes, and his tenure was uneventful. During this period Schuster was very influential in judicial appointments, phrasing his reports in such a way that Finlay could only logically accept one candidate. Although Finlay was not a member of the cabinet (it was a War Cabinet

, with limited representation of ministers) which limited his political influence to some extent, he was close friends with Lord Haldane

and through Haldane Schuster made contacts with up and coming politicians such as Sir Alan Sykes

and Jimmy Thomas

; the group was described as "the future Labour Cabinet". During Findlay's tenure as Lord Chancellor the question of a Ministry of Justice again came up; while the Law Society

was in favour of such a department the Bar Council along with Schuster was opposed to any changes in the status quo, and as the person who prepared a report on the matter for the Lord Chancellor Schuster did his best to express his disapproval of any changes. For his continued work in the Civil Service Schuster was made a Commander of the Royal Victorian Order

in 1918. A year later he was made a King's Counsel: an odd honour for a man who no longer worked as a barrister.

was appointed on 14 January 1919, and was a controversial choice; he was only 46 when appointed and was unpopular with large sections of the Bar as a result; George V

himself wrote to the Prime Minister before Birkenhead was appointed and said that "His Majesty does not feel sure that [Birkenhead] has established such a reputation in men's minds as to ensure that the country will welcome him to the second highest position which can be occupied by a subject of the Crown". Birkenhead and Schuster established a strong partnership, and Schuster played a part in instituting Birkenhead's legal reforms, particularly those relating to the law of real property

.

Real property law in the English and Welsh legal system had evolved from feudalism

, and was an immensely complex system understood by only a small number of lawyers. In particular peculiarities meant that land owned by beneficiaries could be sold without the agreement of all the beneficiaries involved, something partially rectified by the Settled Land Act 1882 and the Land Transfer Act 1897. Despite these statutes reform in this area was still needed, and Lord Haldane presented reform bills to parliament in 1913, 1914 and 1915 with no real progress thanks to the opposition of the Law Society. In March 1917 a Reconstruction Subcommittee under Sir Leslie Scott

was created to consider land policy after the First World War, and Schuster (who had devilled for Scott when working as a barrister in Liverpool) was appointed as a member. The subcommittee decided that the law should be changed to merge real

and personal property

law, and that outdated aspects of land law such as copyhold

s and gavelkind

should be eliminated. When Birkenhead became Lord Chancellor in 1919 he inherited the problem of English property law, and immediately instructed Schuster to prepare the department for forcing a bill through Parliament on the matter.

Although there was general agreement that property law should be reformed the process was made more difficult by the various vested interests involved; the Law Society, for example, was opposed to the changes because it would reduce the fees dedicated property solicitors could earn by making it possible for more solicitors to understand that area of law and become involved. After intense negotiation Schuster and the Law Society representative agreed that a "period of probation" lasting three years would be included in the bill, which Charles Brickdale

the Chief Registrar of HM Land Registry

considered "a very good bargain". When the bill finally got to the House of Commons it met additional opposition from Members of Parliament who were also members of the Law Society and Bar Council, as well as Lord Cave

who later became Lord Chancellor. After further negotiations the bill was passed on 8 June 1922, with Birkenhead taking the credit, and it became the Law of Property Act 1922.

Schuster also assisted Birkenhead in his attempts to reform the administration of the court system, particularly in his preparation of the Supreme Court (Consolidation) Act 1925. A committee was also set up to look into the reform of the Supreme Court, the County Court

s and the Probate Services

, divided into a subcommittee for each institution. Schuster served as a member of the committee, with his primary goal being to end the patronage

and nepotism

that filled the judicial system. Although the Supreme Court was resistant the committee did succeed in making some changes, such as introducing mandatory retirement ages for master

s and clerk

s; they were unable, however, to end the patronage. Schuster also attempted to reform the County Courts by increasing their jurisdiction, and a Committee on County Court Procedure (known as the Swift Committee after its chairman Rigby Swift

) was set up in 1920, with Schuster serving as a member. The commission concluded that HM Treasury

had mismanaged the County Courts, and on 1 August 1922 the Lord Chancellor's Office instead became responsible for the courts, with Schuster becoming Accounting Officer. The committee's final report was used as the basis for the County Courts Act 1924, which did much to correct the problems with the County Courts. Schuster was appointed Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath (KCB) in the 1920 New Year War Honours.

, a member of the new Conservative

government who was appointed on 27 October 1922. The Conservative government under Stanley Baldwin

soon ran into trouble due to his desire to introduce protectionist tariffs

to protect British jobs. Baldwin called an early general election in December 1923

to serve as a referendum on the subject, and although the Conservatives remained the largest party they did not have enough Members of Parliament to claim a parliamentary majority. At the opening of the new Parliament in January 1924 the party was defeated in a vote of no confidence, and the king instead invited the Labour Party

under Ramsay MacDonald

to form a government. This caused various constitutional problems; traditionally every member of a cabinet, including the Prime Minister, must be a Privy Councillor. MacDonald was not a Privy Councillor, and therefore could not be made Prime Minister. The king asked Lord Cave for a way around this problem, and as an expert on constitutional issues Schuster helped draft the response. In the end it was determined that MacDonald would be sworn in as a Privy Councillor and then invited to form a government.

As a member of the old Conservative government Cave left office on 23 January 1924. He was replaced by Lord Haldane

, who was serving for a second time and was sworn in on 25 January. Haldane was in favour of the creation of a Ministry of Justice, and although Schuster was privately against it he suggested that he would have accepted the responsibilities of such a Ministry on the condition that it remained under his control as the Lord Chancellor's Office was. Haldane was ill, however, and the Labour government lasted only ten months thanks to the publishing of the Zinoviev Letter

, and no large-scale reforms such as the creation of a Ministry of Justice were ever pushed through.

became Lord Chancellor for a second time on 7 November. Spending four and a half years in office Cave had time to push through some significant reforms, including the Law of Property Act 1925

based on the 1922 act Schuster had been involved in. By 1925 Schuster had spent a decade as Permanent Secretary and was described as a "Whitehall

Mandarin

", his contacts and long service allowing him greater influence over policy decisions than a Permanent Secretary normally had. The expansion of the Lord Chancellor's Office he had overseen also gave him greater opportunities to delegate to his subordinates, allowing him more time to spend on committees and inquiries directly influencing the way the government worked. As a result of his power and influence he grew to dislike being opposed in any way, and this led to conflict between him and other heads of department. As a reward for his continued service with the Lord Chancellor's Office he was made a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath on 1 January 1927 as part of the New Years Honours.

Lord Cave

resigned on 28 March 1928 due to ill health, and died the day after. His replacement was Lord Hailsham

, who was appointed by Stanley Baldwin

on 29 March 1928. Hailsham's first tenure as Lord Chancellor lasted barely a year and highlighted the fact that despite his abilities (many politicians considered that if he had not accepted the offer to become Lord Chancellor he would likely have become Prime Minister) he was not a particularly innovative Lord Chancellor. For a short period in August 1928 he acted as Prime Minister (Baldwin was on holiday in Aix-en-Provence

) with Schuster as his chief adviser, but he rarely went to 10 Downing Street

and nothing eventful happened during his time in charge.

left office in mid 1929 with the fall of the Conservative

government in 1929. His replacement was a member of the newly elected Labour Government, Lord Sankey

, who was appointed on 8 June 1929. Sankey was appointed on Schuster's advice, and served longer with him than any other Lord Chancellor. Sankey was a "reforming" Lord Chancellor, and as part of one of his first reforms Schuster helped him draft and pass the Statute of Westminster

in 1931.

During this period the question of Judge's salaries also arose, and almost caused a constitutional crisis. As Permanent Secretary Schuster was tasked with ensuring that the courts ran correctly, and although the Judges were independent they were paid by the Lord Chancellor's Office. Although a Select Committee in 1878 had recommended that County Court

Judges be paid £2,000 a year this increase had still failed to appear due to the economic hardships caused by the First World War. The increase was eventually implemented in 1937, but in the meantime High Court

Judges had also been lobbying for an increase, as their pay had stayed at the same level since 1832. Schuster and Warren Fisher

had produced a report recommending a pay increase in 1920, but again the economic hardship prevented their plan from being implemented. The 1931 economic crash led to the government passing the National Recovery Act 1931, which reduced the salaries of High Court Judges by 20%. The Judges, who had been expecting a pay raise rather than a pay cut, were shocked, and six High Court Judges threatened to resign, with Henry McCardie

accusing Schuster of having his salary almost doubled in the last twelve years. The Prime Minister and Sankey met to write a letter to the Judges demanding that they give in; as soon as Schuster heard about this he rushed to Whitehall to "stop the madness". The protests from the Judges increased through 1931 and 1932, with several judges including Albert Clauson

and Arthur Luxmoore

threatening to sue the government. After negotiations between Schuster and the judges failed to bring an end to the crisis the section of the act cutting judges' pay was quietly dropped.

Soon after becoming Permanent Secretary Schuster had decided that his aim should be to make sure that the entire court system was under the control of his office, rather than partially under his control and partially under the control of HM Treasury

as it had been when he started. The 1931 Royal Commission on the Civil Service recommended that all Civil Service departments take a more business-like approach to their work, and spurred Schuster into making a further attempt to reorganise and reform the Lord Chancellor's Office. As such he persuaded Sankey to set up a Departmental Committee on the Business of the Courts, with Lord Hanworth

(one of Schuster's friends) chairing the committee and Schuster himself sitting as a member. As he had under Lord Birkenhead

Schuster attempted to reform the County Courts. Hee partially succeeded in doing when his recommendations were included in the Administration of Justice [Appeals] Act 1934 which sent appeals from the county courts straight to the Court of Appeal

rather than the Divisional Court

s. He also attempted to have the number of jury trials in civil cases reduced, something which Hanworth supported but which was blocked by the King's Bench Division.

Schuster also took part in law reform after Lord Sankey decided to set up a Law Revision Committee in January 1934 which consisted of Sankey, Schuster, four judges, five barristers, one solicitor and two academic lawyers. The committee produced 86 reports from 1934 to 1939 on a variety of subjects, and many of their recommendations were made into legislation after negotiations with the Home Office

. Although the Law Revision Committee fell into disuse after this it was re-formed as a permanent Law Commission

in 1965.

In 1934 Schuster was subject to a public attack by Lord Hewart

, the Lord Chief Justice. On 7 December 1934 his clerk found a bill

amongst Hewart's parliamentary papers with a clause that allowed the Lord Chancellor to appoint any Lord Justice of Appeal

as Vice President of the Chancery Appeal Court

, a right traditionally held by the Lord Chief Justice. Hewart immediately made plans to attend the House of Lords, where Lord Sankey was expected to move the Second Reading

of the bill in question. Immediately after second reading Hewart rose and began a speech that was "as violent an attack as has ever been made in the Lords". In it he criticised the officials of the Lord Chancellor's Department (which to listeners clearly meant Schuster specifically) and insinuated that the bill was part of a conspiracy to move power from the judiciary to the politicians (and thus the civil service) and create a Ministry of Justice. The speech provoked uproar in the house; a public quarrel between senior judges and civil servants had not happened in centuries, especially in such a traditionally calm and collected place. Lord Reading

, himself a former Lord Chief Justice, adjourned the debate, and the following Friday Lord Hailsham

, at the time the Leader of the House of Lords

, made a defence of Schuster, saying that "I can show that this is an absolute delusion [and] that there was no such scheme ever hatched". He showed that the proposal of a Ministry of Justice had originated in 1836, long before Schuster became Permanent Secretary, and in addition that the report Schuster had helped prepare for Sankey was clearly biased against the creation of such a Ministry as he himself was opposed to it. He went on to praise Schuster as "the author and instigator of many great reforms", and along with a similar speech by Lord Sankey and an amendment to the offending bill this helped appease Hewart.

returned to power on 7 June 1935 after the election of a new government, and by this point his health was beginning to decline, limiting his effectiveness. The Second Italo-Abyssinian War

alerted the Civil Service and MI5 to the ambitions of Italy and Germany, and the Committee of Imperial Defence

was asked to review the defence legislation that had been used in the First World War and present it to Warren Fisher

. Fisher was horrified at how outdated the laws were, and with the permission of the Cabinet organised a War Legislation Committee under Schuster to draft a new code of defence regulations. Norman Brook

, later head of the Civil Service, served as secretary, and the Committee was described as "a model piece of organisation" thanks to the work of Schuster as chairman. The regulations drafted by the Committee were eventually made into law after the passing of the Emergency Powers (Defence) Act 1939

.

Lord Hailsham

left his position in 1938 due to his failing health, and was replaced by Lord Maugham

, who was appointed on 15 March. His appointment was done on Schuster's advice and was considered quite a surprise as he had no real political experience; even Maugham himself admitted he had not expected to be offered the job. Schuster and Maugham had a difficult relationship, especially after the start of the Second World War in 1939, due to their differing political opinions. Schuster did not play an active part in policy decisions in this period, partially because of his disagreements with Maugham and partially because Maugham preferred to work on legislation and policy changes himself. Schuster later said that he got on with all of his Lord Chancellors except one—Maugham.

resigned on 3 September 1939, giving his failing health as a reason (he was 73 when he left the post), and he was replaced by Lord Caldecote

a day later. Caldecote only held the office for eight months, but during this period spent a large amount of time preparing legislation for the Second World War. Putting the country on a war footing would impact on the ability of people to fulfil their civil obligations if, for example, they were conscripted, and Schuster was made chairman of a Cabinet subcommittee "to consider the problems arising from the inability of persons, owing to war conditions, to fulfil their contractual and other obligations, and in particular to consider the complaints already made to MPs and government departments". The subcommittee made six reports and their recommendations were eventually made into the Liabilities (Wartime Adjustment) Acts of 1941 and 1944. Schuster also led the committee that drafted the USA (Visiting Forces) Bill that provided that any criminal proceedings in relation to the behaviour of US soldiers stationed in Britain would be led by the US military authorities rather than the British government.

Lord Caldecote

was forced to leave his position after only 8 months due to the fall of Neville Chamberlain

's government, of which he was a part. He was replaced by Lord Simon

, who took up his position on 12 May 1940. Simon frequently delegated to Schuster and accepted his advice on judicial appointments, such as that of Arthur Thompson Denning to the High Court

in 1944. Schuster also had influence in committee appointments; when Simon was asked to select a chairman for the Committee on Reconstruction Priorities he delegated to Schuster, who chose Sir Walter Monckton

.

. By the time he retired Schuster had served as Permanent Secretary for 29 years under 10 Lord Chancellors, records that have not yet been broken. He also served as High Sheriff of Dorset

in 1941.. In retirement he undertook work for the Allied Commission for Austria and "tackled the unexpected with the zest of a young man" despite being 75. He returned to Britain in 1946. He served as Treasurer of the Inner Temple

in 1947, and in 1948 and 1949 took his seat in the House of Lords to voice his opinions on legislation, something he had previously been unable to do publicly due to the tradition of Civil Service neutrality. He participated in debates over the Criminal Justice Act 1948

and Criminal Justice Act 1949, and was noted for being polite to the point of obsequiousness. He gave the Romanes Lecture

in 1949 on the subject of "Mountaineering" and continued to play an active part in public life, helping reconstruct the Inner Temple after it was bombed in the Second World War. On 27 June 1956 he fell ill at an old Wykehamist

dinner and was taken to Charing Cross Hospital

, where he died the next morning.

when he was Rector of Lincoln College, Oxford

and the two became friends due to their shared love of mountaneering. Through him he met Merry's daughter, Elizabeth, who he married in 1896. They had two children: a son, Christopher John Claud Schuster, in 1899 and a daughter, Elizabeth Alice Schuster, in 1902, before Elizabeth Merry's death in 1936. Christopher also attended Winchester College and was killed in 1918 on the Western Front

, and Elizabeth later married Theodore Turner, a King's Counsel, before dying in 1983.

Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate mediæval ceremony for creating a knight, which involved bathing as one of its elements. The knights so created were known as Knights of the Bath...

, CVO

Royal Victorian Order

The Royal Victorian Order is a dynastic order of knighthood and a house order of chivalry recognising distinguished personal service to the order's Sovereign, the reigning monarch of the Commonwealth realms, any members of her family, or any of her viceroys...

, KC (22 August 1869 – 28 June 1956) was a British barrister

Barrister

A barrister is a member of one of the two classes of lawyer found in many common law jurisdictions with split legal professions. Barristers specialise in courtroom advocacy, drafting legal pleadings and giving expert legal opinions...

and civil servant noted for his long tenure as Permanent Secretary to the Lord Chancellor's Office

Permanent Secretary to the Lord Chancellor's Office

The Permanent Secretary to the Lord Chancellor's Department was the most senior civil servant in the Lord Chancellor's Department and a senior member of Her Majesty's Civil Service...

. Born to a middle-class Mancunian

Manchester

Manchester is a city and metropolitan borough in Greater Manchester, England. According to the Office for National Statistics, the 2010 mid-year population estimate for Manchester was 498,800. Manchester lies within one of the UK's largest metropolitan areas, the metropolitan county of Greater...

family, Schuster was educated at St. George's School, Ascot

St. George's School, Ascot

St George's School, Ascot is an independent boarding and day school in Ascot, Berkshire, England. It is now a single-sex girls' school , which selects all of its incoming pupils on the basis of examined ability, usually at age 11, with a few entrants at 13 and 16.-History:The school was founded in...

and Winchester College

Winchester College

Winchester College is an independent school for boys in the British public school tradition, situated in Winchester, Hampshire, the former capital of England. It has existed in its present location for over 600 years and claims the longest unbroken history of any school in England...

before matriculating

Matriculation

Matriculation, in the broadest sense, means to be registered or added to a list, from the Latin matricula – little list. In Scottish heraldry, for instance, a matriculation is a registration of armorial bearings...

at New College, Oxford

New College, Oxford

New College is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom.- Overview :The College's official name, College of St Mary, is the same as that of the older Oriel College; hence, it has been referred to as the "New College of St Mary", and is now almost always...

in 1888 to study history. After graduation he joined the Inner Temple

Inner Temple

The Honourable Society of the Inner Temple, commonly known as Inner Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court in London. To be called to the Bar and practise as a barrister in England and Wales, an individual must belong to one of these Inns...

with the aim of becoming a barrister, and was called to the Bar

Call to the bar

The Call to the Bar is a legal term of art in most common law jurisdictions where persons must be qualified to be allowed to argue in court on behalf of another party, and are then said to have been "called to the bar" or to have received a "call to the bar"...

in 1895. Practising in Liverpool, Schuster was not noted as a particularly successful barrister, and he joined Her Majesty's Civil Service in 1899 as secretary to the Chief Commissioner of the Local Government Act Commission.

After serving as secretary to several more commissions, he was made Permanent Secretary to the Lord Chancellor's Office in 1915. Schuster served in this position for 29 years under ten different Lord Chancellors, and with the contacts obtained thanks to his long tenure and his work outside the Office he became "one of the most influential Permanent Secretaries of the 20th century". His influence over decisions within the Lord Chancellor's Office and greater Civil Service led to criticism and suspicions that he was a "power behind the throne", which culminated in a verbal attack by the Lord Chief Justice Lord Hewart

Gordon Hewart, 1st Viscount Hewart

Gordon Hewart, 1st Viscount Hewart, PC was a politician and judge in the United Kingdom.-Background and education:...

in 1934 during a session of the House of Lords

House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster....

. Schuster retired in 1944 and was made Baron Schuster, of Cerne, in the County of Dorset. Despite being officially retired he continued to work in government circles, such as with the Allied Commission for Austria and by using his seat in the House of Lords as a way to directly criticise legislation.

Early life and education

Unitarianism

Unitarianism is a Christian theological movement, named for its understanding of God as one person, in direct contrast to Trinitarianism which defines God as three persons coexisting consubstantially as one in being....

" but were descended from Jews who had converted to Christianity in the mid-1850s and included other notable people such as Sir Arthur Schuster

Arthur Schuster

Sir Franz Arthur Friedrich Schuster FRS was a German-born British physicist known for his work in spectroscopy, electrochemistry, optics, X-radiography and the application of harmonic analysis to physics...

, Sir Felix Schuster, and later Sir George Schuster. From the age of seven he was educated at St. George's School, Ascot

St. George's School, Ascot

St George's School, Ascot is an independent boarding and day school in Ascot, Berkshire, England. It is now a single-sex girls' school , which selects all of its incoming pupils on the basis of examined ability, usually at age 11, with a few entrants at 13 and 16.-History:The school was founded in...

, one of the most expensive preparatory schools in the country but one known for harsh treatment; it was standard for the headmaster to flog pupils until they bled and force other students and staff to listen to their screams. During the school holidays he accompanied his father to Switzerland, where he developed a life-long love of mountaineering and skiing. He was president of the Alpine Club

Alpine Club (UK)

The Alpine Club was founded in London in 1857 and was probably the world's first mountaineering club. It is UK mountaineering's acknowledged 'senior club'.-History:...

from 1938 to 1940.

When he was fourteen he was sent to Winchester College

Winchester College

Winchester College is an independent school for boys in the British public school tradition, situated in Winchester, Hampshire, the former capital of England. It has existed in its present location for over 600 years and claims the longest unbroken history of any school in England...

, which was known as both the most academic of the main public schools and also for lacking in comfort. Schuster's time at St George's had prepared him for discomfort, however, and he was noted as being very proud of attending the school. While at Winchester Schuster played Winchester College football

Winchester College Football

Winchester College Football, also known as Winkies, WinCoFo or simply "Our Game", is a code of football played at Winchester College. It is akin to the Eton Field and Wall Games and the Harrow Game in that it enjoys a large following from Wykehamists and old Wykehamists but is not played outside...

and was occasionally involved in debates; he was not, however, noted as a particularly exceptional pupil. He matriculated

Matriculation

Matriculation, in the broadest sense, means to be registered or added to a list, from the Latin matricula – little list. In Scottish heraldry, for instance, a matriculation is a registration of armorial bearings...

at New College, Oxford

New College, Oxford

New College is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom.- Overview :The College's official name, College of St Mary, is the same as that of the older Oriel College; hence, it has been referred to as the "New College of St Mary", and is now almost always...

in 1888 and graduated with a second-class degree in history in 1892; again he was not noted as a particularly outstanding student, which was attributed to the time he spent enjoying himself rather than studying. Despite his lack of academic brilliance he was invited to present the Romanes Lecture

Romanes Lecture

The Romanes Lecture is a prestigious free public lecture given annually at the Sheldonian Theatre, Oxford, England.The lecture series was founded by, and named after, the biologist George Romanes, and has been running since 1892. Over the years, many notable figures from the Arts and Sciences have...

in 1949, an honour normally only given to the most eminent alumni of Oxford. After graduation he applied to become a Fellow of All Souls College, Oxford

All Souls College, Oxford

The Warden and the College of the Souls of all Faithful People deceased in the University of Oxford or All Souls College is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England....

but was rejected.

Bar work and career change

Inner Temple

The Honourable Society of the Inner Temple, commonly known as Inner Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court in London. To be called to the Bar and practise as a barrister in England and Wales, an individual must belong to one of these Inns...

and was called to the bar in 1895. He practised in Liverpool and, though he was not noted as a particularly successful barrister, he became Circuit Junior of the Northern Circuit Bar in late 1895, an important position. By this point Schuster was married and required a steady income to support his family, something which the bar was not providing. With his love of the English language and the knowledge that he was "good with paper" Schuster decided to join Civil Service, with the intention of becoming a Permanent Secretary

Permanent Secretary

The Permanent secretary, in most departments officially titled the permanent under-secretary of state , is the most senior civil servant of a British Government ministry, charged with running the department on a day-to-day basis...

.

Schuster entered the Civil Service in 1899 and as a qualified lawyer was exempt from the required examinations, something that marked him as "different" from other civil service employees with whom he worked. His first post was as secretary to the Chief Commissioner of the Local Government Act Commission, which produced a report leading to the creation of the London County Council

London County Council

London County Council was the principal local government body for the County of London, throughout its 1889–1965 existence, and the first London-wide general municipal authority to be directly elected. It covered the area today known as Inner London and was replaced by the Greater London Council...

. After this he worked as a secretary to the Great Northern Railway

Great Northern Railway (Great Britain)

The Great Northern Railway was a British railway company established by the Great Northern Railway Act of 1846. On 1 January 1923 the company lost its identity as a constituent of the newly formed London and North Eastern Railway....

and then for the workers' union at London & Smith's Bank Ltd. After his job at the union he was noticed by Robert Morant

Robert Laurie Morant

Sir Robert Laurie Morant was an English administrator and educationalist He was educated at Winchester College and New College, Oxford....

who employed him as a temporary legal assistant to the Board of Education

Board of education

A board of education or a school board or school committee is the title of the board of directors or board of trustees of a school, local school district or higher administrative level....

on the understanding that the job would become permanent, which it did in 1907. In 1911 he was promoted to Principal Assistant Secretary, and after Morant was appointed to the English Commission under the National Insurance Act 1911

National Insurance Act 1911

The National Insurance Act 1911 is an Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom. The Act is often regarded as one of the foundations of modern social welfare in the United Kingdom and forms part of the wider social welfare reforms of the Liberal Government of 1906-1914...

Schuster followed him by being appointed Chief Registrar of the Friendly Societies, which granted him a place on the Societies' committee.

In February 1912 he gave up his position as Chief Registrar to become Secretary (and then legal adviser) to the English Insurance Commission, with the newspapers of the time reporting that he had had "three promotions in two months", a consequence of his high standing with Morant. During this period he was also involved in drafting education bills with Arthur Thring. The commission was "a galaxy of future Whitehall stars", and contained many individuals who would later become noted civil servants in their own right, including Morant, Schuster, John Anderson

John Anderson, 1st Viscount Waverley

John Anderson, 1st Viscount Waverley, GCB, OM, GCSI, GCIE, PC, PC was a British civil servant then politician who served as a minister under Neville Chamberlain and Winston Churchill as Home Secretary, Lord President of the Council and Chancellor of the Exchequer...

, Warren Fisher

Warren Fisher

Sir Warren Fisher was a British civil servant.Fisher was born in Croydon, London on 22 September 1879. He was educated at the Dragon School , Winchester College and Hertford College, Oxford University...

and John Bradbury. The contacts Schuster made during his time on the committee were instrumental in advancing his career; as a lawyer rather than a dedicated civil servant he was considered an outsider, and the links he made – particularly the friendships he struck up with Fisher and Anderson – helped allay this to some extent.

He was knighted in 1913 for his services on various committees.

Permanent Secretary to the Lord Chancellor's Office

In 1915 Sir Kenneth Muir MackenzieKenneth Muir Mackenzie, 1st Baron Muir-Mackenzie

Kenneth Augustus Muir Mackenzie, 1st Baron Muir Mackenzie GCB, PC, QC , was a British barrister, civil servant and Labour politician.-Background and education:...

, who had served as Permanent Secretary to the Lord Chancellor's Office, was close to retirement. The current Lord Chancellor Lord Haldane

Richard Haldane, 1st Viscount Haldane

Richard Burdon Haldane, 1st Viscount Haldane KT, OM, PC, KC, FRS, FBA, FSA , was an influential British Liberal Imperialist and later Labour politician, lawyer and philosopher. He was Secretary of State for War between 1905 and 1912 during which time the "Haldane Reforms" were implemented...

believed that the duties of a Lord Chancellor were too much for one man, and should be divided between a Lord Chancellor and a Minister of Justice. As such he looked for a Permanent Secretary who was a qualified lawyer and who could help him set up a Ministry of Justice after the war, appointing Schuster in early 1915. The two did not work together, however, until Haldane became Lord Chancellor for a second time in 1924; he was forced to resign several months before Schuster started work on 2 July 1915 after being accused of pro-German sympathies.

Lords Buckmaster and Findlay (1915–1916, 1916–1919)

The first Lord Chancellor under whom Schuster served was Lord BuckmasterStanley Buckmaster, 1st Viscount Buckmaster

Stanley Owen Buckmaster, 1st Viscount Buckmaster, GCVO, PC, KC was a British lawyer and Liberal politician. He was Lord Chancellor under H. H...

, who was appointed on 27 May 1915. Although most senior government offices at this time were held by wealthy aristocrats, the office of Lord Chancellor stood out as most of the appointees were lawyers from the middle class. Buckmaster was considered "the most plebeian

Plebs

The plebs was the general body of free land-owning Roman citizens in Ancient Rome. They were distinct from the higher order of the patricians. A member of the plebs was known as a plebeian...

of Lord Chancellors", as he was the son of a farmer and schoolteacher who later became a Justice of the Peace

Justice of the Peace

A justice of the peace is a puisne judicial officer elected or appointed by means of a commission to keep the peace. Depending on the jurisdiction, they might dispense summary justice or merely deal with local administrative applications in common law jurisdictions...

. Schuster became Permanent Secretary in July, a month after Buckmaster took his post, and immediately tried to make an impression on the workings of the office by modernising it; under the previous Permanent Secretary – who abhorred time-saving mechanisms – shorthand had been forbidden, and the office had owned only one typewriter. Buckmaster and Schuster had similar outlooks on World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, with both their sons serving on the Western Front

Western Front (World War I)

Following the outbreak of World War I in 1914, the German Army opened the Western Front by first invading Luxembourg and Belgium, then gaining military control of important industrial regions in France. The tide of the advance was dramatically turned with the Battle of the Marne...

; Schuster almost certainly helped write the 1915 memorandum Buckmaster circulated to the Westminster Cabinet

Cabinet (government)

A Cabinet is a body of high ranking government officials, typically representing the executive branch. It can also sometimes be referred to as the Council of Ministers, an Executive Council, or an Executive Committee.- Overview :...

arguing that forces should be concentrated on the Western Front rather than spread out in an attempt to assault other areas.

H. H. Asquith

H. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith, KG, PC, KC served as the Liberal Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1908 to 1916...

resigned as Prime Minister in December 1916, and as a member of Asquith's cabinet Buckmaster followed him. He was replaced by Lord Finlay

Robert Finlay, 1st Viscount Finlay

Robert Bannatyne Finlay, 1st Viscount Finlay GCMG, PC, QC,MD was a British lawyer, doctor and politician who became Lord Chancellor of Great Britain.-Background and education:...

who was appointed on 12 December. Aged 74 when he was appointed, Finlay was the oldest person to be made Lord Chancellor other than Lord Campbell

John Campbell, 1st Baron Campbell

John Campbell, 1st Baron Campbell PC, KC was a British Liberal politician, lawyer, and man of letters.-Background and education:...

, who was 80 when he was appointed in 1859, and his age showed, with his decisions being slow and cautious. Luckily the job of the Lord Chancellor during the last two years of World War I was limited to maintaining the system rather than instituting any changes, and his tenure was uneventful. During this period Schuster was very influential in judicial appointments, phrasing his reports in such a way that Finlay could only logically accept one candidate. Although Finlay was not a member of the cabinet (it was a War Cabinet

War Cabinet

A War Cabinet is a committee formed by a government in a time of war. It is usually a subset of the full executive cabinet of ministers. It is also quite common for a War Cabinet to have senior military officers and opposition politicians as members....

, with limited representation of ministers) which limited his political influence to some extent, he was close friends with Lord Haldane

Richard Haldane, 1st Viscount Haldane

Richard Burdon Haldane, 1st Viscount Haldane KT, OM, PC, KC, FRS, FBA, FSA , was an influential British Liberal Imperialist and later Labour politician, lawyer and philosopher. He was Secretary of State for War between 1905 and 1912 during which time the "Haldane Reforms" were implemented...

and through Haldane Schuster made contacts with up and coming politicians such as Sir Alan Sykes

Sir Alan Sykes, 1st Baronet

Sir Alan John Sykes, 1st Baronet was an English businessman in the bleaching industry and Conservative politician in Cheshire....

and Jimmy Thomas

James Henry Thomas

James Henry "Jimmy" Thomas was a British trade unionist and Labour politician. He was involved in a political scandal involving budget leaks.-Early career and Trade Union activities:...

; the group was described as "the future Labour Cabinet". During Findlay's tenure as Lord Chancellor the question of a Ministry of Justice again came up; while the Law Society

Law Society of England and Wales

The Law Society is the professional association that represents the solicitors' profession in England and Wales. It provides services and support to practising and training solicitors as well as serving as a sounding board for law reform. Members of the Society are often consulted when important...

was in favour of such a department the Bar Council along with Schuster was opposed to any changes in the status quo, and as the person who prepared a report on the matter for the Lord Chancellor Schuster did his best to express his disapproval of any changes. For his continued work in the Civil Service Schuster was made a Commander of the Royal Victorian Order

Royal Victorian Order

The Royal Victorian Order is a dynastic order of knighthood and a house order of chivalry recognising distinguished personal service to the order's Sovereign, the reigning monarch of the Commonwealth realms, any members of her family, or any of her viceroys...

in 1918. A year later he was made a King's Counsel: an odd honour for a man who no longer worked as a barrister.

Lord Birkenhead (1919–1922)

Finlay had been appointed on the conditions that he would not claim a pension (it was war-time, and there were already four retired Lord Chancellors claiming £5000 per year pensions) and that he would resign when required. Despite this he was surprised when he was dismissed after the 1919 general election, first hearing about it when it was mentioned in the newspapers. His replacement Lord BirkenheadF. E. Smith, 1st Earl of Birkenhead

Frederick Edwin Smith, 1st Earl of Birkenhead GCSI, PC, KC , best known to history as F. E. Smith , was a British Conservative statesman and lawyer of the early 20th century. He was a skilled orator, noted for his staunch opposition to Irish nationalism, his wit, pugnacious views, and hard living...

was appointed on 14 January 1919, and was a controversial choice; he was only 46 when appointed and was unpopular with large sections of the Bar as a result; George V

George V of the United Kingdom

George V was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 through the First World War until his death in 1936....

himself wrote to the Prime Minister before Birkenhead was appointed and said that "His Majesty does not feel sure that [Birkenhead] has established such a reputation in men's minds as to ensure that the country will welcome him to the second highest position which can be occupied by a subject of the Crown". Birkenhead and Schuster established a strong partnership, and Schuster played a part in instituting Birkenhead's legal reforms, particularly those relating to the law of real property

Real property

In English Common Law, real property, real estate, realty, or immovable property is any subset of land that has been legally defined and the improvements to it made by human efforts: any buildings, machinery, wells, dams, ponds, mines, canals, roads, various property rights, and so forth...

.

Real property law in the English and Welsh legal system had evolved from feudalism

Feudalism

Feudalism was a set of legal and military customs in medieval Europe that flourished between the 9th and 15th centuries, which, broadly defined, was a system for ordering society around relationships derived from the holding of land in exchange for service or labour.Although derived from the...

, and was an immensely complex system understood by only a small number of lawyers. In particular peculiarities meant that land owned by beneficiaries could be sold without the agreement of all the beneficiaries involved, something partially rectified by the Settled Land Act 1882 and the Land Transfer Act 1897. Despite these statutes reform in this area was still needed, and Lord Haldane presented reform bills to parliament in 1913, 1914 and 1915 with no real progress thanks to the opposition of the Law Society. In March 1917 a Reconstruction Subcommittee under Sir Leslie Scott

Leslie Scott (UK politician)

Sir Leslie Frederic Scott, KC, PC was a Conservative Party politician in the United Kingdom, and later a senior judge....

was created to consider land policy after the First World War, and Schuster (who had devilled for Scott when working as a barrister in Liverpool) was appointed as a member. The subcommittee decided that the law should be changed to merge real

Real property

In English Common Law, real property, real estate, realty, or immovable property is any subset of land that has been legally defined and the improvements to it made by human efforts: any buildings, machinery, wells, dams, ponds, mines, canals, roads, various property rights, and so forth...

and personal property

Personal property

Personal property, roughly speaking, is private property that is moveable, as opposed to real property or real estate. In the common law systems personal property may also be called chattels or personalty. In the civil law systems personal property is often called movable property or movables - any...

law, and that outdated aspects of land law such as copyhold

Copyhold

At its origin in medieval England, copyhold tenure was tenure of land according to the custom of the manor, the "title deeds" being a copy of the record of the manorial court....

s and gavelkind

Gavelkind

Gavelkind was a system of land tenure associated chiefly with the county of Kent, but found also in other parts of England. Its inheritance pattern bears resemblance to Salic patrimony and as such might testify in favour of a wider, probably ancient Germanic tradition.It was legally abolished in...

should be eliminated. When Birkenhead became Lord Chancellor in 1919 he inherited the problem of English property law, and immediately instructed Schuster to prepare the department for forcing a bill through Parliament on the matter.

Although there was general agreement that property law should be reformed the process was made more difficult by the various vested interests involved; the Law Society, for example, was opposed to the changes because it would reduce the fees dedicated property solicitors could earn by making it possible for more solicitors to understand that area of law and become involved. After intense negotiation Schuster and the Law Society representative agreed that a "period of probation" lasting three years would be included in the bill, which Charles Brickdale

Charles Brickdale

Sir Charles Fortescue Brickdale was a British barrister and civil servant best known for his reform of HM Land Registry as Chief Registrar.-Life:...

the Chief Registrar of HM Land Registry

HM Land Registry

Land Registry is a non-ministerial government department and executive agency of the Government of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1862 to register the ownership of land and property in England and Wales...

considered "a very good bargain". When the bill finally got to the House of Commons it met additional opposition from Members of Parliament who were also members of the Law Society and Bar Council, as well as Lord Cave

George Cave, 1st Viscount Cave

George Cave, 1st Viscount Cave GCMG, KC, PC was a British lawyer and Conservative politician. He was Home Secretary under David Lloyd George from 1916 to 1919 and served as Lord Chancellor of Great Britain from 1922 to 1924 and again from 1924 to 1928.-Background and education:Cave was born in...

who later became Lord Chancellor. After further negotiations the bill was passed on 8 June 1922, with Birkenhead taking the credit, and it became the Law of Property Act 1922.

Schuster also assisted Birkenhead in his attempts to reform the administration of the court system, particularly in his preparation of the Supreme Court (Consolidation) Act 1925. A committee was also set up to look into the reform of the Supreme Court, the County Court

County Court

A county court is a court based in or with a jurisdiction covering one or more counties, which are administrative divisions within a country, not to be confused with the medieval system of county courts held by the High Sheriff of each county.-England and Wales:County Court matters can be lodged...

s and the Probate Services

Probate

Probate is the legal process of administering the estate of a deceased person by resolving all claims and distributing the deceased person's property under the valid will. A probate court decides the validity of a testator's will...

, divided into a subcommittee for each institution. Schuster served as a member of the committee, with his primary goal being to end the patronage

Patronage

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows to another. In the history of art, arts patronage refers to the support that kings or popes have provided to musicians, painters, and sculptors...

and nepotism

Nepotism

Nepotism is favoritism granted to relatives regardless of merit. The word nepotism is from the Latin word nepos, nepotis , from which modern Romanian nepot and Italian nipote, "nephew" or "grandchild" are also descended....

that filled the judicial system. Although the Supreme Court was resistant the committee did succeed in making some changes, such as introducing mandatory retirement ages for master

Master (judiciary)

A Master is judicial officer found in the courts of England and in numerous other jurisdictions based on the common law tradition. A master's jurisdiction is generally confined to civil proceedings and is a subset of that of a judge. Masters are typically involved in hearing motions, case...

s and clerk

Law clerk

A law clerk or a judicial clerk is a person who provides assistance to a judge in researching issues before the court and in writing opinions. Law clerks are not court clerks or courtroom deputies, who are administrative staff for the court. Most law clerks are recent law school graduates who...

s; they were unable, however, to end the patronage. Schuster also attempted to reform the County Courts by increasing their jurisdiction, and a Committee on County Court Procedure (known as the Swift Committee after its chairman Rigby Swift

Rigby Swift

Sir Rigby Philip Watson Swift KC was a British barrister, Member of Parliament and judge. Born into a family of solicitors and barristers, Swift was educated at Parkfield School before taking up a place in his father's chambers and at the same time studying for his LLB at the University of London...

) was set up in 1920, with Schuster serving as a member. The commission concluded that HM Treasury

HM Treasury

HM Treasury, in full Her Majesty's Treasury, informally The Treasury, is the United Kingdom government department responsible for developing and executing the British government's public finance policy and economic policy...

had mismanaged the County Courts, and on 1 August 1922 the Lord Chancellor's Office instead became responsible for the courts, with Schuster becoming Accounting Officer. The committee's final report was used as the basis for the County Courts Act 1924, which did much to correct the problems with the County Courts. Schuster was appointed Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath (KCB) in the 1920 New Year War Honours.

Lords Cave and Haldane (1922–1924, 1924)

By the summer of 1922 the coalition government Birkenhead was a member of began to splinter, and when it finally collapsed Birkenhead was forced to resign on 25 October 1922. His replacement was Lord CaveGeorge Cave, 1st Viscount Cave

George Cave, 1st Viscount Cave GCMG, KC, PC was a British lawyer and Conservative politician. He was Home Secretary under David Lloyd George from 1916 to 1919 and served as Lord Chancellor of Great Britain from 1922 to 1924 and again from 1924 to 1928.-Background and education:Cave was born in...

, a member of the new Conservative

Conservative Party (UK)

The Conservative Party, formally the Conservative and Unionist Party, is a centre-right political party in the United Kingdom that adheres to the philosophies of conservatism and British unionism. It is the largest political party in the UK, and is currently the largest single party in the House...

government who was appointed on 27 October 1922. The Conservative government under Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley, KG, PC was a British Conservative politician, who dominated the government in his country between the two world wars...

soon ran into trouble due to his desire to introduce protectionist tariffs

Protectionism

Protectionism is the economic policy of restraining trade between states through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, restrictive quotas, and a variety of other government regulations designed to allow "fair competition" between imports and goods and services produced domestically.This...

to protect British jobs. Baldwin called an early general election in December 1923

United Kingdom general election, 1923

-Seats summary:-References:*F. W. S. Craig, British Electoral Facts: 1832-1987*-External links:***...

to serve as a referendum on the subject, and although the Conservatives remained the largest party they did not have enough Members of Parliament to claim a parliamentary majority. At the opening of the new Parliament in January 1924 the party was defeated in a vote of no confidence, and the king instead invited the Labour Party

Labour Party (UK)

The Labour Party is a centre-left democratic socialist party in the United Kingdom. It surpassed the Liberal Party in general elections during the early 1920s, forming minority governments under Ramsay MacDonald in 1924 and 1929-1931. The party was in a wartime coalition from 1940 to 1945, after...

under Ramsay MacDonald

Ramsay MacDonald

James Ramsay MacDonald, PC, FRS was a British politician who was the first ever Labour Prime Minister, leading a minority government for two terms....

to form a government. This caused various constitutional problems; traditionally every member of a cabinet, including the Prime Minister, must be a Privy Councillor. MacDonald was not a Privy Councillor, and therefore could not be made Prime Minister. The king asked Lord Cave for a way around this problem, and as an expert on constitutional issues Schuster helped draft the response. In the end it was determined that MacDonald would be sworn in as a Privy Councillor and then invited to form a government.

As a member of the old Conservative government Cave left office on 23 January 1924. He was replaced by Lord Haldane

Richard Haldane, 1st Viscount Haldane

Richard Burdon Haldane, 1st Viscount Haldane KT, OM, PC, KC, FRS, FBA, FSA , was an influential British Liberal Imperialist and later Labour politician, lawyer and philosopher. He was Secretary of State for War between 1905 and 1912 during which time the "Haldane Reforms" were implemented...

, who was serving for a second time and was sworn in on 25 January. Haldane was in favour of the creation of a Ministry of Justice, and although Schuster was privately against it he suggested that he would have accepted the responsibilities of such a Ministry on the condition that it remained under his control as the Lord Chancellor's Office was. Haldane was ill, however, and the Labour government lasted only ten months thanks to the publishing of the Zinoviev Letter

Zinoviev Letter

The "Zinoviev Letter" refers to a controversial document published by the British press in 1924, allegedly sent from the Communist International in Moscow to the Communist Party of Great Britain...

, and no large-scale reforms such as the creation of a Ministry of Justice were ever pushed through.

Lords Cave and Hailsham (1924–1928, 1928–1929)

After the collapse of the Labour government in October 1924 the Conservative Party returned to power, and Lord CaveGeorge Cave, 1st Viscount Cave

George Cave, 1st Viscount Cave GCMG, KC, PC was a British lawyer and Conservative politician. He was Home Secretary under David Lloyd George from 1916 to 1919 and served as Lord Chancellor of Great Britain from 1922 to 1924 and again from 1924 to 1928.-Background and education:Cave was born in...

became Lord Chancellor for a second time on 7 November. Spending four and a half years in office Cave had time to push through some significant reforms, including the Law of Property Act 1925

Law of Property Act 1925

The Law of Property Act 1925 is a statute of the United Kingdom Parliament. It forms part of an interrelated programme of legisation introduced by Lord Chancellor Lord Birkenhead between 1922 and 1925. The programme was intended to modernise the English law of real property...

based on the 1922 act Schuster had been involved in. By 1925 Schuster had spent a decade as Permanent Secretary and was described as a "Whitehall

Whitehall

Whitehall is a road in Westminster, in London, England. It is the main artery running north from Parliament Square, towards Charing Cross at the southern end of Trafalgar Square...

Mandarin

Mandarin (bureaucrat)

A mandarin was a bureaucrat in imperial China, and also in the monarchist days of Vietnam where the system of Imperial examinations and scholar-bureaucrats was adopted under Chinese influence.-History and use of the term:...

", his contacts and long service allowing him greater influence over policy decisions than a Permanent Secretary normally had. The expansion of the Lord Chancellor's Office he had overseen also gave him greater opportunities to delegate to his subordinates, allowing him more time to spend on committees and inquiries directly influencing the way the government worked. As a result of his power and influence he grew to dislike being opposed in any way, and this led to conflict between him and other heads of department. As a reward for his continued service with the Lord Chancellor's Office he was made a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath on 1 January 1927 as part of the New Years Honours.

Lord Cave

George Cave, 1st Viscount Cave

George Cave, 1st Viscount Cave GCMG, KC, PC was a British lawyer and Conservative politician. He was Home Secretary under David Lloyd George from 1916 to 1919 and served as Lord Chancellor of Great Britain from 1922 to 1924 and again from 1924 to 1928.-Background and education:Cave was born in...

resigned on 28 March 1928 due to ill health, and died the day after. His replacement was Lord Hailsham

Douglas Hogg, 1st Viscount Hailsham

Douglas McGarel Hogg, 1st Viscount Hailsham PC was a British lawyer and Conservative politician.-Background:...

, who was appointed by Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley, KG, PC was a British Conservative politician, who dominated the government in his country between the two world wars...

on 29 March 1928. Hailsham's first tenure as Lord Chancellor lasted barely a year and highlighted the fact that despite his abilities (many politicians considered that if he had not accepted the offer to become Lord Chancellor he would likely have become Prime Minister) he was not a particularly innovative Lord Chancellor. For a short period in August 1928 he acted as Prime Minister (Baldwin was on holiday in Aix-en-Provence

Aix-en-Provence

Aix , or Aix-en-Provence to distinguish it from other cities built over hot springs, is a city-commune in southern France, some north of Marseille. It is in the region of Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur, in the département of Bouches-du-Rhône, of which it is a subprefecture. The population of Aix is...

) with Schuster as his chief adviser, but he rarely went to 10 Downing Street

10 Downing Street

10 Downing Street, colloquially known in the United Kingdom as "Number 10", is the headquarters of Her Majesty's Government and the official residence and office of the First Lord of the Treasury, who is now always the Prime Minister....

and nothing eventful happened during his time in charge.

Lord Sankey (1929–1935)

Lord HailshamDouglas Hogg, 1st Viscount Hailsham

Douglas McGarel Hogg, 1st Viscount Hailsham PC was a British lawyer and Conservative politician.-Background:...

left office in mid 1929 with the fall of the Conservative

Conservative Party (UK)

The Conservative Party, formally the Conservative and Unionist Party, is a centre-right political party in the United Kingdom that adheres to the philosophies of conservatism and British unionism. It is the largest political party in the UK, and is currently the largest single party in the House...

government in 1929. His replacement was a member of the newly elected Labour Government, Lord Sankey

John Sankey, 1st Viscount Sankey

John Sankey, 1st Viscount Sankey GBE, KStJ, PC, KC was a prominent British lawyer, judge and Labour politician, famous for many of his judgments in the House of Lords...

, who was appointed on 8 June 1929. Sankey was appointed on Schuster's advice, and served longer with him than any other Lord Chancellor. Sankey was a "reforming" Lord Chancellor, and as part of one of his first reforms Schuster helped him draft and pass the Statute of Westminster

Statute of Westminster 1931

The Statute of Westminster 1931 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Passed on 11 December 1931, the Act established legislative equality for the self-governing dominions of the British Empire with the United Kingdom...

in 1931.

During this period the question of Judge's salaries also arose, and almost caused a constitutional crisis. As Permanent Secretary Schuster was tasked with ensuring that the courts ran correctly, and although the Judges were independent they were paid by the Lord Chancellor's Office. Although a Select Committee in 1878 had recommended that County Court

County Court

A county court is a court based in or with a jurisdiction covering one or more counties, which are administrative divisions within a country, not to be confused with the medieval system of county courts held by the High Sheriff of each county.-England and Wales:County Court matters can be lodged...

Judges be paid £2,000 a year this increase had still failed to appear due to the economic hardships caused by the First World War. The increase was eventually implemented in 1937, but in the meantime High Court

High Court of Justice

The High Court of Justice is, together with the Court of Appeal and the Crown Court, one of the Senior Courts of England and Wales...

Judges had also been lobbying for an increase, as their pay had stayed at the same level since 1832. Schuster and Warren Fisher

Warren Fisher

Sir Warren Fisher was a British civil servant.Fisher was born in Croydon, London on 22 September 1879. He was educated at the Dragon School , Winchester College and Hertford College, Oxford University...

had produced a report recommending a pay increase in 1920, but again the economic hardship prevented their plan from being implemented. The 1931 economic crash led to the government passing the National Recovery Act 1931, which reduced the salaries of High Court Judges by 20%. The Judges, who had been expecting a pay raise rather than a pay cut, were shocked, and six High Court Judges threatened to resign, with Henry McCardie

Henry McCardie

Sir Henry Alfred McCardie was a controversial British judge. Educated at King Edward's School, Birmingham he left school at 16 and spent several years working for an auctioneer before qualifying as a barrister and being called to the Bar in 1894...

accusing Schuster of having his salary almost doubled in the last twelve years. The Prime Minister and Sankey met to write a letter to the Judges demanding that they give in; as soon as Schuster heard about this he rushed to Whitehall to "stop the madness". The protests from the Judges increased through 1931 and 1932, with several judges including Albert Clauson

Albert Clauson, 1st Baron Clauson

Albert Charles Clauson, 1st Baron Clauson CBE KC PC was a British barrister and judge who sat as a Lord Justice of Appeal.-Background and education:...

and Arthur Luxmoore

Arthur Luxmoore

Sir Arthur Fairfax Charles Coryndon Luxmoore KC PC was a British barrister and judge who sat as a Lord Justice of Appeal-Life:...

threatening to sue the government. After negotiations between Schuster and the judges failed to bring an end to the crisis the section of the act cutting judges' pay was quietly dropped.

Soon after becoming Permanent Secretary Schuster had decided that his aim should be to make sure that the entire court system was under the control of his office, rather than partially under his control and partially under the control of HM Treasury

HM Treasury

HM Treasury, in full Her Majesty's Treasury, informally The Treasury, is the United Kingdom government department responsible for developing and executing the British government's public finance policy and economic policy...

as it had been when he started. The 1931 Royal Commission on the Civil Service recommended that all Civil Service departments take a more business-like approach to their work, and spurred Schuster into making a further attempt to reorganise and reform the Lord Chancellor's Office. As such he persuaded Sankey to set up a Departmental Committee on the Business of the Courts, with Lord Hanworth

Ernest Pollock, 1st Viscount Hanworth

Ernest Murray Pollock, 1st Viscount Hanworth KBE PC KC was a British Conservative Member of Parliament and Master of the Rolls.He was the MP for Warwick and Leamington from 1910 to 1923...

(one of Schuster's friends) chairing the committee and Schuster himself sitting as a member. As he had under Lord Birkenhead

F. E. Smith, 1st Earl of Birkenhead

Frederick Edwin Smith, 1st Earl of Birkenhead GCSI, PC, KC , best known to history as F. E. Smith , was a British Conservative statesman and lawyer of the early 20th century. He was a skilled orator, noted for his staunch opposition to Irish nationalism, his wit, pugnacious views, and hard living...

Schuster attempted to reform the County Courts. Hee partially succeeded in doing when his recommendations were included in the Administration of Justice [Appeals] Act 1934 which sent appeals from the county courts straight to the Court of Appeal

Court of Appeal of England and Wales

The Court of Appeal of England and Wales is the second most senior court in the English legal system, with only the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom above it...

rather than the Divisional Court

Divisional Court

A Divisional Court, in relation to the High Court of Justice of England and Wales, means a court sitting with at least two judges. Matters heard by a Divisional Court include some criminal cases in the High Court as well as certain judicial review cases...

s. He also attempted to have the number of jury trials in civil cases reduced, something which Hanworth supported but which was blocked by the King's Bench Division.

Schuster also took part in law reform after Lord Sankey decided to set up a Law Revision Committee in January 1934 which consisted of Sankey, Schuster, four judges, five barristers, one solicitor and two academic lawyers. The committee produced 86 reports from 1934 to 1939 on a variety of subjects, and many of their recommendations were made into legislation after negotiations with the Home Office

Home Office