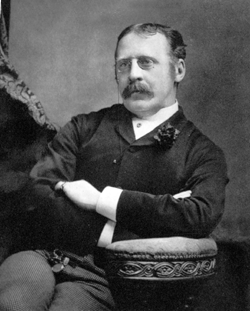

Clement Scott

Encyclopedia

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

theatre critic for the Daily Telegraph, and a playwright and travel writer, in the final decades of the 19th century. His style of criticism - acerbic, flowery, and (perhaps most importantly) carried out on the first night of productions, set the standard for theatre reviewers through to today.

Life and career

Born the son of William Scott, the vicar of HoxtonHoxton

Hoxton is an area in the London Borough of Hackney, immediately north of the financial district of the City of London. The area of Hoxton is bordered by Regent's Canal on the north side, Wharf Road and City Road on the west, Old Street on the south, and Kingsland Road on the east.Hoxton is also a...

in north London, Clement William Scott converted to Roman Catholicism before his 21st birthday. Educated at Marlborough College

Marlborough College

Marlborough College is a British co-educational independent school for day and boarding pupils, located in Marlborough, Wiltshire.Founded in 1843 for the education of the sons of Church of England clergy, the school now accepts both boys and girls of all beliefs. Currently there are just over 800...

, he became a civil servant, working in the War Office

War Office

The War Office was a department of the British Government, responsible for the administration of the British Army between the 17th century and 1964, when its functions were transferred to the Ministry of Defence...

beginning in 1860.

Early career

Encouraged to write by the humorist Tom HoodTom Hood

Tom Hood , was an English humorist and playwright, son of the poet and author Thomas Hood. A prolific author, he was appointed, in 1865, editor of the magazine Fun. He also founded Tom Hood's Comic Annual in 1867....

the younger, who also was a clerk in the War Office, Scott contributed to Era, Weekly Dispatch, and to Hood's own paper, Fun

Fun (magazine)

Fun was a Victorian weekly magazine, first published on 21 September 1861. The magazine was founded by the actor and playwright H. J. Byron in competition with Punch magazine.-Description:...

, where Scott and W. S. Gilbert

W. S. Gilbert

Sir William Schwenck Gilbert was an English dramatist, librettist, poet and illustrator best known for his fourteen comic operas produced in collaboration with the composer Sir Arthur Sullivan, of which the most famous include H.M.S...

were colleagues. Scott's interest in writing and the theatre led him to brief dalliance with the failed Victoria Review.

He became the dramatic writer for The Sunday Times

The Sunday Times (UK)

The Sunday Times is a Sunday broadsheet newspaper, distributed in the United Kingdom. The Sunday Times is published by Times Newspapers Ltd, a subsidiary of News International, which is in turn owned by News Corporation. Times Newspapers also owns The Times, but the two papers were founded...

in 1863 but held the position for only two years because of the intemperance of his published opinions and his unpopular praise of the French theatre. In 1871, Scott began his nearly thirty years as a theatre critic with The Daily Telegraph

The Daily Telegraph

The Daily Telegraph is a daily morning broadsheet newspaper distributed throughout the United Kingdom and internationally. The newspaper was founded by Arthur B...

. He also contributed regularly to Theatre magazine and wrote sentimental poetry and song lyrics (including "Oh Promise Me

Oh Promise Me

Oh Promise Me is a song with music by Reginald De Koven and lyrics by Clement Scott. The song was written in 1887 and first published in 1889 as an art song. De Koven may have based the melody partly on an aria by Stanislao Gastaldon, "Musica Proibita". In 1890, De Koven wrote his most...

"), which were often published in the magazine Punch by his friend, the editor, F. C. Burnand. Scott continued to work at the War Office until 1879, when he finally decided to earn his living entirely by writing.

As well as criticism, Scott wrote plays, including The Vicarage, The Cape Mail, Anne Mié, Odette, and The Great Divorce Case. He wrote several English adaptations of Victorien Sardou

Victorien Sardou

Victorien Sardou was a French dramatist. He is best remembered today for his development, along with Eugène Scribe, of the well-made play...

's plays, some of which were written in collaboration with B. C. Stephenson

B. C. Stephenson

Benjamin Charles Stephenson or B. C. Stephenson was an English dramatist, lyricist and librettist. After beginning a career in the civil service, he started to write for the theatre, using the pen name "Bolton Rowe". He was author or co-author of several long-running shows of the Victorian theatre...

, such as Nos intimes (as Peril) and Dora (1878, as Diplomacy). The latter was described by the theatrical paper The Era

The Era (newspaper)

The Era was a British weekly paper, published from 1838 to 1939. Originally a general newspaper, it became noted for its sports coverage, and later for its theatrical content.-History:...

as "the great dramatic hit of the season". It also played with success at Wallack's Theatre

Wallack's Theatre

Wallack’s Theatre , located on 254 West 42nd Street in New York, United States, was opened on December 5, 1904 by Oscar Hammerstein I. Wallack’s was Hammerstein’s 8th production theatre and was originally known as the "Lew Fields'", a name that Hammerstein gave it in recognition of his favourite...

in New York. Scott and Stephenson also wrote an English version of Halévy

Ludovic Halévy

Ludovic Halévy was a French author and playwright. He was half Jewish : his Jewish father had converted to Christianity prior to his birth, to marry his mother, née Alexandrine Lebas.-Biography:Ludovic Halévy was born in Paris...

and Meilhac

Henri Meilhac

Henri Meilhac , was a French dramatist and opera librettist.-Biography:Meilhac was born in Paris in 1831. As a young man, he began writing fanciful articles for Parisian newspapers and vaudevilles, in a vivacious boulevardier spirit which brought him to the forefront...

's libretto for Lecocq's operetta Le Petit Duc (1878). Their adaptation so pleased the composer that he volunteered to write some new music for the English production. For all of these, Scott adopted the pen name "Saville Rowe" (after Savile Row

Savile Row

Savile Row is a shopping street in Mayfair, central London, famous for its traditional men's bespoke tailoring. The term "bespoke" is understood to have originated in Savile Row when cloth for a suit was said to "be spoken for" by individual customers...

) to match Stephenson's pseudonym, "Bolton Rowe", another Mayfair street. The pieces with Stephenson were produced by the Bancrofts

Squire Bancroft

Sir Squire Bancroft , born Squire White Butterfield, was an English actor-manager. He and his wife Effie Bancroft are considered to have instigated a new form of drama known as 'drawing-room comedy' or 'cup and saucer drama', owing to the realism of their stage sets.-Early life and career:Bancroft...

, the producers of T. W. Robertson

Thomas William Robertson

Thomas William Robertson , usually known professionally as T. W. Robertson, was an Anglo-Irish dramatist and innovative stage director best known for a series of realistic or naturalistic plays produced in London in the 1860s that broke new ground and inspired playwrights such as W.S...

's plays, which Scott admired. He also wrote accounts of holiday tours around the British Isles

British Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands off the northwest coast of continental Europe that include the islands of Great Britain and Ireland and over six thousand smaller isles. There are two sovereign states located on the islands: the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and...

and abroad, becoming known for his florid style. Scott's travels also inspired his creative writing. After a tour of New Zealand

New Zealand

New Zealand is an island country in the south-western Pacific Ocean comprising two main landmasses and numerous smaller islands. The country is situated some east of Australia across the Tasman Sea, and roughly south of the Pacific island nations of New Caledonia, Fiji, and Tonga...

, he wrote "Now Is the Hour

Now Is the Hour

"Now Is the Hour" is a popular song, though often described as a traditional Māori song. It is usually credited to Clement Scott, Maewa Kaihau & Dorothy Stewart....

" (Haere Ra) known as the Māori farewell song, based on a traditional New Zealand melody, which is also used as the tune for the hymn "Search Me, O God" with lyrics by J. Edwin Orr

J. Edwin Orr

James Edwin Orr was a Baptist minister, lecturer and author.At the time of his death, J. Edwin Orr was professor emeritus of the history of awakenings at Fuller Theological Seminary's School of World Missions. He had been born in the North of Ireland of American-British parentage. He had a Ph....

.

Poppyland and later life

In 1883, the Daily Telegraph printed an article which Scott had written about a visit to the north Norfolk coast. He became enamoured of the district and gave it the name Poppyland. His writing was responsible for members of the London theatre set visiting and investing in homes in the area. It is there that he is perhaps best remembered, but ironically, he was unhappy at the result of his popularization of this previously pristine area.Scott married Isobel du Maurier, and the couple had four children. Du Maurier died in 1890, and he remarried Margarite Brandon, a journalist, in San Francisco. Scott's long-time wish to be elected a member of the famous literary gentlemen's club, the Garrick Club

Garrick Club

The Garrick Club is a gentlemen's club in London.-History:The Garrick Club was founded at a meeting in the Committee Room at Theatre Royal, Drury Lane on Wednesday 17 August 1831...

(to which Henry Irving

Henry Irving

Sir Henry Irving , born John Henry Brodribb, was an English stage actor in the Victorian era, known as an actor-manager because he took complete responsibility for season after season at the Lyceum Theatre, establishing himself and his company as...

, Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan

Arthur Sullivan

Sir Arthur Seymour Sullivan MVO was an English composer of Irish and Italian ancestry. He is best known for his series of 14 operatic collaborations with the dramatist W. S. Gilbert, including such enduring works as H.M.S. Pinafore, The Pirates of Penzance and The Mikado...

, among many other notable men belonged), was finally realized in 1892. Scott worked for a couple of years at the end of the century for the New York Herald

New York Herald

The New York Herald was a large distribution newspaper based in New York City that existed between May 6, 1835, and 1924.-History:The first issue of the paper was published by James Gordon Bennett, Sr., on May 6, 1835. By 1845 it was the most popular and profitable daily newspaper in the UnitedStates...

, later returning to London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

. In 1900, he founded The Free Lance, a Popular Society and Critical Journal, for writers who worked by the job, which he edited.

Scott died in Norfolk at the age of 62.

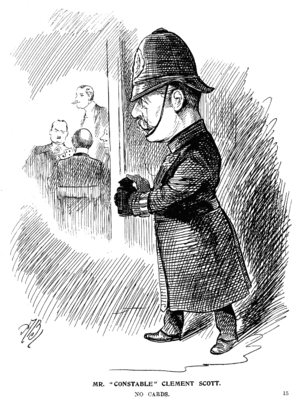

Style, controversies and influence

William Archer (critic)

William Archer , Scottish critic, was born in Perth, and was educated at the University of Edinburgh, where he received the degree of M.A. in 1876. He was the son of Thomas Archer....

, the chief English supporter of Ibsen

Henrik Ibsen

Henrik Ibsen was a major 19th-century Norwegian playwright, theatre director, and poet. He is often referred to as "the father of prose drama" and is one of the founders of Modernism in the theatre...

, combined to involve him in frequent and prolonged controversy.

Scott especially became embroiled in legal claims through his outspoken criticism of various actors and actresses. Early in his career, he wrote approvingly of the "cup and saucer" realism movement, led by T. W. Robertson, whose plays were notable for treating contemporary British subjects in realistic settings. Later, he favoured the grand and spectacular type of London theatrical production which had developed with new types of theatre building, electric lighting and technologies allowed more and more adventurous staging. As time went on, he became strongly conservative and opposed to the new drama of Ibsen and Shaw

George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw was an Irish playwright and a co-founder of the London School of Economics. Although his first profitable writing was music and literary criticism, in which capacity he wrote many highly articulate pieces of journalism, his main talent was for drama, and he wrote more than 60...

, arguing that domestic intrigue, sexual situations and wordy philosophising were inappropriate for an evening at the theatre, and even harmful to society, especially young women. The verdict of history has been that Scott was wrong.

Scott played an important part in encouraging a more attentive attitude by theatre audiences. In his early days, it was not uncommon for audiences to be very boisterous and noisy, frequently booing and talking during productions, especially through the overture. He also insisted on first night reviews. It had been common for reviewers to wait a few days before writing about a production. Scott insisted that the paying audience on the first night should expect to see a fully fledged production, and not one where the leading characters did not know all their lines. He also supported actor-managers of his time by providing them with translations of popular French plays and with his own plays.

His papers are located in the library of Rochester University, New York State. Film maker John Madden

John Madden (director)

John Philip Madden is an English director of theatre, film, television, and radio.- Biography :Madden was educated at Clifton College. He was in the same house as friend and fellow director Roger Michell. He began his career in British independent films, and graduated from the University of...

(Shakespeare in Love

Shakespeare in Love

Shakespeare in Love is a 1998 British-American comedy film directed by John Madden and written by Marc Norman and playwright Tom Stoppard....

, Mrs. Brown, Captain Corelli's Mandolin

Captain Corelli's Mandolin

Captain Corelli's Mandolin, released simultaneously as Corelli's Mandolin. in the United States, is a 1994 novel written by Louis de Bernières which takes place on the island of Cephallonia during the Italian and German occupation of World War II. The main characters are Antonio Corelli, an...

) made his first feature film for the BBC around the story of Scott's visit to Poppyland.