Condemnations (University of Paris)

Encyclopedia

University of Paris

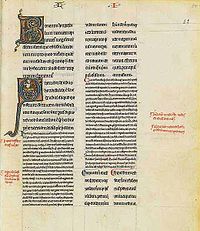

The University of Paris was a university located in Paris, France and one of the earliest to be established in Europe. It was founded in the mid 12th century, and officially recognized as a university probably between 1160 and 1250...

were enacted to restrict certain teachings as being heretical. These included a number of medieval theological teachings, but most importantly the physical treatises of Aristotle

Aristotelian physics

Aristotelian Physics the natural sciences, are described in the works of the Greek philosopher Aristotle . In the Physics, Aristotle established general principles of change that govern all natural bodies; both living and inanimate, celestial and terrestrial—including all motion, change in respect...

. The investigations of these teachings were conducted by the Bishops of Paris. The Condemnations of 1277 are traditionally linked to an investigation requested by Pope John XXI

Pope John XXI

Pope John XXI, , born Pedro Julião Pope John XXI, , born Pedro Julião Pope John XXI, , born Pedro Julião (Latin, Petrus Iulianus (c. 1215 – May 20, 1277), a Portuguese also called Pedro Hispano (Latin, Petrus Hispanus; English, Peter of Spain), was Pope from 1276 until his death about eight...

, although whether he actually supported drawing up a list of condemnations is unclear.

Approximately sixteen lists of censured theses were issued by the University of Paris during the 13th and 14th centuries. Most of these lists of propositions were put together into systematic collections of prohibited articles. Of these, the Condemnations of 1277 are considered particularly important by historians as they allowed scholars to break from the restrictions of Aristotelian science. This had positive effects on the development of science, with some historians going so far as to claim that they represented the beginnings of modern science.

Condemnation of 1210

The Condemnation of 1210 was issued by the provincial synod of SensSens

Sens is a commune in the Yonne department in Burgundy in north-central France.Sens is a sub-prefecture of the department. It is crossed by the Yonne and the Vanne, which empties into the Yonne here.-History:...

, which included the Bishop of Paris as a member (at the time Peter of Nemours). The writings of a number of medieval scholars were condemned, apparently for pantheism

Pantheism

Pantheism is the view that the Universe and God are identical. Pantheists thus do not believe in a personal, anthropomorphic or creator god. The word derives from the Greek meaning "all" and the Greek meaning "God". As such, Pantheism denotes the idea that "God" is best seen as a process of...

, and it was further stated that: "Neither the books of Aristotle

Aristotle

Aristotle was a Greek philosopher and polymath, a student of Plato and teacher of Alexander the Great. His writings cover many subjects, including physics, metaphysics, poetry, theater, music, logic, rhetoric, linguistics, politics, government, ethics, biology, and zoology...

on natural philosophy or their commentaries are to be read at Paris in public or secret, and this we forbid under penalty of excommunication

Excommunication

Excommunication is a religious censure used to deprive, suspend or limit membership in a religious community. The word means putting [someone] out of communion. In some religions, excommunication includes spiritual condemnation of the member or group...

." However, this had only local force, and its application was further restricted to the Arts faculty at the University of Paris

University of Paris

The University of Paris was a university located in Paris, France and one of the earliest to be established in Europe. It was founded in the mid 12th century, and officially recognized as a university probably between 1160 and 1250...

. Theologians

Theology

Theology is the systematic and rational study of religion and its influences and of the nature of religious truths, or the learned profession acquired by completing specialized training in religious studies, usually at a university or school of divinity or seminary.-Definition:Augustine of Hippo...

were therefore left free to read the prohibited works, the titles of which were not even specified. Alexander of Aphrodisias

Alexander of Aphrodisias

Alexander of Aphrodisias was a Peripatetic philosopher and the most celebrated of the Ancient Greek commentators on the writings of Aristotle. He was a native of Aphrodisias in Caria, and lived and taught in Athens at the beginning of the 3rd century, where he held a position as head of the...

was probably among the Aristotelian commentators whose influence was targeted.

The University of Toulouse

University of Toulouse

The Université de Toulouse is a consortium of French universities, grandes écoles and other institutions of higher education and research, named after one of the earliest universities established in Europe in 1229, and including the successor universities to that earlier university...

(founded in 1229) tried to capitalise on the situation by advertising itself to students: "Those who wish to scrutinize the bosom of nature to the inmost can hear the books of Aristotle which were forbidden at Paris." However, whether the prohibition had actually had an effect on the study of the physical texts in Paris is unclear. English scholars, including Robert Grosseteste

Robert Grosseteste

Robert Grosseteste or Grossetete was an English statesman, scholastic philosopher, theologian and Bishop of Lincoln. He was born of humble parents at Stradbroke in Suffolk. A.C...

and Roger Bacon

Roger Bacon

Roger Bacon, O.F.M. , also known as Doctor Mirabilis , was an English philosopher and Franciscan friar who placed considerable emphasis on the study of nature through empirical methods...

, studied at Paris, when they could have chosen to study at the University of Oxford

University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a university located in Oxford, United Kingdom. It is the second-oldest surviving university in the world and the oldest in the English-speaking world. Although its exact date of foundation is unclear, there is evidence of teaching as far back as 1096...

, where the works could still be discussed in public. It is assumed that at the least they continued to be read in Paris in private, and there are also signs that their discussion had become public by 1240.

Condemnation of 1270

By 1270, the ban on Aristotle's natural philosophy was a dead letter. Nevertheless the Bishop of Paris, Étienne TempierÉtienne Tempier

Étienne Tempier was a French bishop of Paris during the 13th century...

, convened a meeting of conservative theologians and in December 1270 banned the teaching of certain Aristotelian and Averroist doctrines at Paris. Thirteen propositions were listed as false and heretical, some relating to Averroes' doctrine of the soul

Soul

A soul in certain spiritual, philosophical, and psychological traditions is the incorporeal essence of a person or living thing or object. Many philosophical and spiritual systems teach that humans have souls, and others teach that all living things and even inanimate objects have souls. The...

and the doctrine of monopsychism

Monopsychism

Monopsychism is the belief that all humans share one and the same eternal consciousness, soul, mind or intellect. It is a recurring theme in many mystical traditions....

, and others directed against Aristotle's theory of God as a passive Unmoved Mover

Unmoved mover

The unmoved mover is a philosophical concept described by Aristotle as a primary cause or "mover" of all the motion in the universe. As is implicit in the name, the "unmoved mover" is not moved by any prior action...

. The banned propositions included:

- "That there is numerically one and the same intellect for all humans".

- "That the soul separated [from the body] by death cannot suffer from bodily fire".

- "That God cannot grant immortality and incorruption to a mortal and corruptible thing".

- "That God does not know singulars".

- "That God does not know things other than Himself".

- "That human acts are not ruled by the providence of GodDivine ProvidenceIn Christian theology, divine providence, or simply providence, is God's activity in the world. " Providence" is also used as a title of God exercising His providence, and then the word are usually capitalized...

". - "That the world is eternal".

- "That there was never a first human".

Those who "knowingly" taught or asserted them as true would suffer automatic excommunication, with the implied threat of the medieval Inquisition

Medieval Inquisition

The Medieval Inquisition is a series of Inquisitions from around 1184, including the Episcopal Inquisition and later the Papal Inquisition...

if they persisted. It is not known which of these statements were "taught knowingly" or "asserted" by teachers at Paris, although Siger of Brabant

Siger of Brabant

Siger of Brabant was a 13th century philosopher from the southern Low Countries who was an important proponent of Averroism...

and his radical Averroist colleagues at the Faculty of Arts were targets. Evidently, the radical masters had taught that Aristotle put forward controversial propositions — which according to the Averroists could have been true at least in philosophy — and questions such as free will

Free will

"To make my own decisions whether I am successful or not due to uncontrollable forces" -Troy MorrisonA pragmatic definition of free willFree will is the ability of agents to make choices free from certain kinds of constraints. The existence of free will and its exact nature and definition have long...

and the immortality of the soul were doubtless subject to scholarly debate between masters and students. However, it seems "inconceivable" that any teacher would deny God's Providence or present the Aristotelian "Unmoved Mover" as the true God.

Condemnation of 1277

Catholic Encyclopedia

The Catholic Encyclopedia, also referred to as the Old Catholic Encyclopedia and the Original Catholic Encyclopedia, is an English-language encyclopedia published in the United States. The first volume appeared in March 1907 and the last three volumes appeared in 1912, followed by a master index...

records that the theologians of the University of Paris had been very uneasy due to the antagonism that existed between Christian dogmas

Dogma

Dogma is the established belief or doctrine held by a religion, or a particular group or organization. It is authoritative and not to be disputed, doubted, or diverged from, by the practitioners or believers...

and certain Peripatetic doctrines. According to the historian Edward Grant

Edward Grant

Edward Grant is an American historian. He was named a Distinguished Professor in 1983. Other honors include the 1992 George Sarton Medal, for "a lifetime scholarly achievement" as an historian of science.-Biography:...

, the theologians desired to condemn Aristotle's teachings on the eternity of the world

Eternity of the world

The question of the eternity of the world was a concern of the philosophers of the classical period and particularly the medieval theologians and philosophers of the 13th century. The problem is whether the world has a beginning in time, or whether it has existed from eternity...

and the unicity of the intellect.

On 18 January 1277, Pope John XXI

Pope John XXI

Pope John XXI, , born Pedro Julião Pope John XXI, , born Pedro Julião Pope John XXI, , born Pedro Julião (Latin, Petrus Iulianus (c. 1215 – May 20, 1277), a Portuguese also called Pedro Hispano (Latin, Petrus Hispanus; English, Peter of Spain), was Pope from 1276 until his death about eight...

instructed Bishop Tempier to investigate the complaints of the theologians. "Not only did Tempier investigate but in only three weeks, on his own authority, he issued a condemnation of 219 propositions drawn from many sources, including, apparently, the works of Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, O.P. , also Thomas of Aquin or Aquino, was an Italian Dominican priest of the Catholic Church, and an immensely influential philosopher and theologian in the tradition of scholasticism, known as Doctor Angelicus, Doctor Communis, or Doctor Universalis...

, some of whose ideas found their way onto the list." The list published on 7 March condemned a great number of "errors", some of which emanated from the astrology

Astrology

Astrology consists of a number of belief systems which hold that there is a relationship between astronomical phenomena and events in the human world...

, and others from the philosophy of the Peripatetics. These included:

- 9. "That there was no first man, nor will there be a last; on the contrary, there always was and always will be generation of man from man."

- 49. "That God could not move the heavens with rectilinear motion; and the reason is that a vacuum would remain."

- 87. "That the world is eternal as to all the species contained in it; and that time is eternal, as are motion, matter, agent, and recipient; and because the world is from the infinite power of God, it is impossible that there be novelty in an effect without novelty in the cause."

The penalty for anyone teaching or listening to the listed errors was excommunication, "unless they turned themselves in to the bishop or the chancellor within seven days, in which case the bishop would inflict proportionate penalties." The condemnation sought to stop the Master of Arts

Master of Arts (postgraduate)

A Master of Arts from the Latin Magister Artium, is a type of Master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The M.A. is usually contrasted with the M.S. or M.Sc. degrees...

teachers from interpreting the works of Aristotle in ways that were contrary to the beliefs of the Church. In addition to the 219 errors, the condemnation also covered Andreas Capellanus

Andreas Capellanus

Andreas Capellanus was the 12th-century author of a treatise commonly known as De amore , and often known in English, somewhat misleadingly, as The Art of Courtly Love, though its realistic, somewhat cynical tone suggests that it is in some measure an antidote to courtly love...

's De amore

De amore (Andreas Capellanus)

Andreas Capellanus was the twelfth century author of a treatise commonly titled De amore , also known as De arte honeste amandi, for which a possible English translation is The Art of Courtly Love...

, and unnamed or unidentified treatises on geomancy

Geomancy

Geomancy is a method of divination that interprets markings on the ground or the patterns formed by tossed handfuls of soil, rocks, or sand...

, necromancy

Necromancy

Necromancy is a claimed form of magic that involves communication with the deceased, either by summoning their spirit in the form of an apparition or raising them bodily, for the purpose of divination, imparting the ability to foretell future events or discover hidden knowledge...

, witchcraft

Witchcraft

Witchcraft, in historical, anthropological, religious, and mythological contexts, is the alleged use of supernatural or magical powers. A witch is a practitioner of witchcraft...

, or fortunetelling.

The condemnation of 1277 was later annulled because of its complications with the teachings of Thomas Aquinas.

Assessment

Pierre Mandonnet

Pierre Mandonnet was a Belgian Dominican historian, important in the neo-Thomist trend of historiography and the recovery of medieval philosophy. He made his reputation with a study of Siger of Brabant....

, numbering and distinguishing the 179 philosophical theses from the 40 theological ones. The list was summarised into groupings and further explained by John F. Wippel. It has also been emphasised by the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy is a freely-accessible online encyclopedia of philosophy maintained by Stanford University. Each entry is written and maintained by an expert in the field, including professors from over 65 academic institutions worldwide...

that "Tempier's theses express positions that cannot be maintained in light of revealed truth, and for this reason are each followed by the qualification 'error'."

Another problem was that Tempier did not identify the targets of his condemnation, merely indicating that it was directed against unspecified members of the Arts Faculty in Paris. Siger of Brabant

Siger of Brabant

Siger of Brabant was a 13th century philosopher from the southern Low Countries who was an important proponent of Averroism...

and Boethius of Dacia have been singled out as the most prominent targets of the 1277 censure, even though their names are not found in the document itself, appearing instead in the rubrics of only two of the many manuscripts that preserve the condemnation. These two scholars were important proponents of the Averroist movement

Averroism

Averroism is the term applied to either of two philosophical trends among scholastics in the late 13th century: the Arab philosopher Averroës or Ibn Rushd's interpretations of Aristotle and his reconciliation of Aristotelianism with Islamic faith; and the application of these ideas in the Latin...

. The ground-breaking study by the historian Roland Hissette has shown that many of the censured propositions appear have come from Aristotle, from Arab philosophers, or from "the philosophers" (i.e. other Greek philosophers).

The role that Pope John XXI played in the lead up to the condemnations is a more recent point of discussion. Because the papal letter preceded Tempier's condemnation by only about six weeks, the traditional assumption was that Tempier had acted on papal initiative, and in an overzealous and hasty way. However, more than forty days after Tempier produced his list, another papal letter gives no indication that the Pope was as yet aware of Tempier's action, and seems to suggest otherwise. It is therefore possible that Tempier had already been preparing his condemnations prior to receiving the Pope's first letter. The Pope himself had not played any direct role in the condemnations, having merely requested an investigation, and one scholar has argued that there was "less than enthusiastic papal approval of the bishop of Paris' actions."

Effects

Pierre Duhem

Pierre Maurice Marie Duhem was a French physicist, mathematician and philosopher of science, best known for his writings on the indeterminacy of experimental criteria and on scientific development in the Middle Ages...

considered that these condemnations "destroyed certain essential foundations of Peripatetic physics". Although the Aristotelian system viewed propositions such as the existence of a vacuum to be ridiculously untenable, belief in Divine Omnipotence

Omnipotence

Omnipotence is unlimited power. Monotheistic religions generally attribute omnipotence to only the deity of whichever faith is being addressed...

sanctioned them as possible, whilst waiting for science to confirm them as true. From at least 1280 onward, many masters at Paris and Oxford admitted that the laws of nature are certainly opposed to the production of empty space, but that the realisation of such a space is not, in itself, contrary to reason. These arguments gave rise to the branch of mechanical science

Classical mechanics

In physics, classical mechanics is one of the two major sub-fields of mechanics, which is concerned with the set of physical laws describing the motion of bodies under the action of a system of forces...

known as dynamics.

Pierre Duhem

Pierre Duhem

Pierre Maurice Marie Duhem was a French physicist, mathematician and philosopher of science, best known for his writings on the indeterminacy of experimental criteria and on scientific development in the Middle Ages...

and Edward Grant state this caused a break from Aristotle’s work and forced the teachers of the time to believe Aristotle’s work imperfect. According to Duhem, "if we must assign a date for the birth of modern science, we would, without doubt, choose the year 1277 when the bishop of Paris solemnly proclaimed that several worlds could exist, and that the whole of heavens could, without contradiction, be moved with a rectilinear motion."

Duhem's view has been extremely influential in the historiography

Historiography

Historiography refers either to the study of the history and methodology of history as a discipline, or to a body of historical work on a specialized topic...

of medieval science, and opened it up as a serious academic discipline. "Duhem believed that Tempier, with his insistence of God's absolute power, had liberated Christian thought from the dogmatic acceptance of Aristotelianism

Aristotelianism

Aristotelianism is a tradition of philosophy that takes its defining inspiration from the work of Aristotle. The works of Aristotle were initially defended by the members of the Peripatetic school, and, later on, by the Neoplatonists, who produced many commentaries on Aristotle's writings...

, and in this way marked the birth of modern science." The condemnations certainly had a positive effect on science, but scholars disagree over their relative influence. Historians in the field no longer fully endorse his view that modern science started in 1277. Edward Grant is probably the contemporary historian of science who comes closest to Duhem's vision. What historians do agree is that the condemnations allowed science "to consider possibilities that the great philosopher never envisioned." According to the historian of science Richard Dales, they "seem definitely to have promoted a freer and more imaginative way of doing science."

Others point out that in philosophy, a critical and skeptical reaction followed on from the Condemnations 1277. Since the theologians had shown that Aristotle had erred in theology, and pointed out the disastrous consequences of uncritical acceptance of his ideas, scholastic philosophers such as Duns Scotus

Duns Scotus

Blessed John Duns Scotus, O.F.M. was one of the more important theologians and philosophers of the High Middle Ages. He was nicknamed Doctor Subtilis for his penetrating and subtle manner of thought....

and William of Ockham

William of Ockham

William of Ockham was an English Franciscan friar and scholastic philosopher, who is believed to have been born in Ockham, a small village in Surrey. He is considered to be one of the major figures of medieval thought and was at the centre of the major intellectual and political controversies of...

(both Franciscan

Franciscan

Most Franciscans are members of Roman Catholic religious orders founded by Saint Francis of Assisi. Besides Roman Catholic communities, there are also Old Catholic, Anglican, Lutheran, ecumenical and Non-denominational Franciscan communities....

friars) believed he might also be mistaken in matters of philosophy. The Scotist and Ockhamist movements set Scholasticism

Scholasticism

Scholasticism is a method of critical thought which dominated teaching by the academics of medieval universities in Europe from about 1100–1500, and a program of employing that method in articulating and defending orthodoxy in an increasingly pluralistic context...

on a different path from that of Albert the Great and Aquinas, and the theological motivation of their philosophical arguments can be traced right back to 1277. They stressed the traditional Franciscan themes of Divine Omnipotence and Divine Freedom, which formed part of Ockham's first thesis.

Ockham's second thesis was the principle of parsimony: also known as Ockham's razor

Occam's razor

Occam's razor, also known as Ockham's razor, and sometimes expressed in Latin as lex parsimoniae , is a principle that generally recommends from among competing hypotheses selecting the one that makes the fewest new assumptions.-Overview:The principle is often summarized as "simpler explanations...

. This developed a new form of logic, based on an empiricist theory of knowledge. "While Scholastic in setting," as David Lindberg writes, it was "thoroughly modern in orientation. Referred to as the via moderna, in opposition to the via antiqua of the earlier scholastics, it has been seen as a forerunner of a modern age of analysis." Other, even more skeptical thinkers in the mid-14th century included John of Mirecourt

John of Mirecourt

John of Mirecourt was a Cistercian scholastic philosopher of the fourteenth century, from Lorraine. He was a follower of William of Ockham; he was censured by Pope Clement VI.-References:...

and Nicholas of Autrecourt

Nicholas of Autrecourt

Nicholas of Autrecourt was a French medieval philosopher and Scholastic theologian....

. The new philosophy of nature, that emerged from the rise of Skepticism

Skepticism

Skepticism has many definitions, but generally refers to any questioning attitude towards knowledge, facts, or opinions/beliefs stated as facts, or doubt regarding claims that are taken for granted elsewhere...

following the Condemnations, contained "the seeds from which modern science could arise in the early seventeenth century."

See also

- History of science in the Middle Ages

- Medieval universityMedieval universityMedieval university is an institution of higher learning which was established during High Middle Ages period and is a corporation.The first institutions generally considered to be universities were established in Italy, France, and England in the late 11th and the 12th centuries for the study of...

- Renaissance of the 12th centuryRenaissance of the 12th centuryThe Renaissance of the 12th century was a period of many changes at the outset of the High Middle Ages. It included social, political and economic transformations, and an intellectual revitalization of Western Europe with strong philosophical and scientific roots...

External links

- Duhem, Pierre, "History of Physics", from the Catholic EncyclopediaCatholic EncyclopediaThe Catholic Encyclopedia, also referred to as the Old Catholic Encyclopedia and the Original Catholic Encyclopedia, is an English-language encyclopedia published in the United States. The first volume appeared in March 1907 and the last three volumes appeared in 1912, followed by a master index...

- "Right, for the wrong reason" from The EconomistThe EconomistThe Economist is an English-language weekly news and international affairs publication owned by The Economist Newspaper Ltd. and edited in offices in the City of Westminster, London, England. Continuous publication began under founder James Wilson in September 1843...

. - Thijssen, Hans, "Condemnation of 1277" from the Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyStanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyThe Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy is a freely-accessible online encyclopedia of philosophy maintained by Stanford University. Each entry is written and maintained by an expert in the field, including professors from over 65 academic institutions worldwide...

.