Copernican heliocentrism

Encyclopedia

Copernican heliocentrism is the name given to the astronomical model developed by Nicolaus Copernicus

and published in 1543. It positioned the Sun

near the center of the Universe

, motionless, with Earth and the other planets rotating around it in circular paths modified by epicycles and at uniform speeds. The Copernican model departed from the Ptolemaic

system that prevailed in Western culture

for centuries, placing Earth at the center of the Universe, and is often regarded as the launching point to modern astronomy

and the Scientific Revolution

.

As a university-trained Catholic priest dedicated to astronomy, Copernicus was acquainted with the Sun-centered cosmos of the ancient Greek Aristarchus

. Although he circulated an outline of the heliocentric theory to colleagues decades earlier, the idea was largely forgotten until late in his life he was urged by a pupil to complete and publish a mathematically detailed account of his model. Copernicus's challenge was to present a practical alternative to the Ptolemaic model by more elegantly and accurately determining the length of a solar year while preserving the metaphysical

implications of a mathematically ordered cosmos. Thus his heliocentric model retained several of the Ptolemaic elements causing the inaccuracies, such as the planets' circular orbits, epicycles, and uniform speeds, while at the same time re-introducing such innovations as:

(4th century BC) was also one of the first to hypothesize movement of the Earth, probably inspired by Pythagoras

' theories about a spherical globe. Aristarchus of Samos

in the 3rd century BC had developed some theories of Heraclides Ponticus

(speaking of a revolution by Earth on its axis) to propose what was, so far as is known, the first serious model of a heliocentric solar system. His work about a heliocentric system has not survived, so one may only speculate about what led him to his conclusions. It is notable that, according to Plutarch, a contemporary of Aristarchus accused him of impiety for "putting the Earth in motion."

Several Muslim astronomers, such as Ibn al-Haytham, Abu-Rayhan Biruni, Abu Said Sinjari, Najm al-Dīn al-Qazwīnī al-Kātibī

, and Qutb al-Din al-Shirazi

also discussed the possibility of heliocentrism.

Copernicus cited Aristarchus and Philolaus in an early manuscript of his book which survives, stating: "Philolaus believed in the mobility of the earth, and some even say that Aristarchus of Samos was of that opinion." For reasons unknown (although possibly out of reluctance to quote pre-Christian sources), he did not include this passage in the publication of his book. Inspiration came to Copernicus not from observation of the planets, but from reading two authors. In Cicero

he found an account of the theory of Hicetas

. Plutarch

provided an account of the Pythagoreans Heraclides Ponticus

, Philolaus

, and Ecphantes. These authors had proposed a moving Earth, which did not, however, revolve around a central sun. When Copernicus' book was published, it contained an unauthorized preface by the Lutheran theologian Andreas Osiander

. This cleric stated that Copernicus wrote his heliocentric account of the Earth's movement as a mere mathematical hypothesis, not as an account that contained truth or even probability. Since Copernicus' hypothesis was believed to contradict the Old Testament

account of the Sun's movement around the Earth (Joshua

10:12-13), this was apparently written to soften any religious backlash against the book. However, there is no evidence that Copernicus himself considered the heliocentric model as merely mathematically convenient, separate from reality.

, Mo'ayyeduddin Urdi

, Nasir al-Din al-Tusi

, and Ibn al-Shatir

for geocentric models of planetary motions closely resemble some of those used later by Copernicus in his heliocentric models. This has led some scholars to argue that Copernicus must have had access to some yet to be identified work on the ideas of those earlier astronomers. However, no likely candidate for this conjectured work has yet come to light, and other scholars have argued that Copernicus could well have developed these ideas independently of the Islamic tradition. Copernicus also discusses the theories of Al-Battani

and Averroes

in his major work.

, dating from about 150 A.D. Throughout the Middle Ages

it was spoken of as the authoritative text on astronomy, although its author remained a little understood figure frequently mistaken as one of the Ptolemaic rulers

of Egypt. The Ptolemaic system drew on many previous theories that viewed Earth as a stationary center of the universe. Stars were embedded in a large outer sphere which rotated relatively rapidly, while the planets dwelt in smaller spheres between—a separate one for each planet. To account for apparent anomalies in this view, such as the apparent retrograde motion of the planets, a system of deferents and epicycles

was used. The planet was said to revolve in a small circle (the epicycle) about a center, which itself revolved in a larger circle (the deferent) about a center on or near the Earth.

A complementary theory to Ptolemy's employed homocentric spheres: the spheres within which the planets rotated, could themselves rotate somewhat. This theory predated Ptolemy (it was first devised by Eudoxus of Cnidus

; by the time of Copernicus it was associated with Averroes

). Also popular with astronomers were variations such as eccentrics

—by which the rotational axis was offset and not completely at the center.

Ptolemy's unique contribution to this theory was the equant

—a point about which the center of a planet's epicycle moved with uniform angular velocity, but which was offset from the center of its deferent. This violated one of the fundamental principles of Aristotelian cosmology—namely, that the motions of the planets should be explained in terms of uniform circular motion, and was considered a serious defect by many medieval astronomers. In Copernicus's day, the most up-to-date version of the Ptolemaic system was that of Peurbach (1423–1461) and Regiomontanus

(1436–1476).

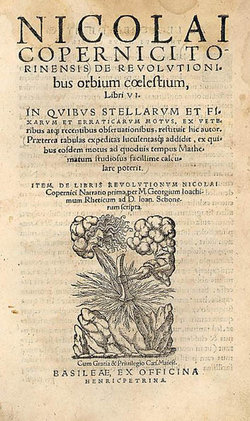

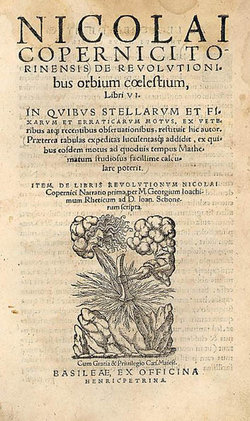

Copernicus' major work, De revolutionibus orbium coelestium

Copernicus' major work, De revolutionibus orbium coelestium

- On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres (first edition 1543 in Nuremberg, second edition 1566 in Basel

), was published during the year of his death, though he had arrived at his theory several decades earlier. The book marks the beginning of the shift away from a geocentric (and anthropocentric

) universe with the Earth at its center. Copernicus held that the Earth is another planet

revolving around the fixed sun once a year, and turning on its axis once a day. But while Copernicus put the Sun at the center of the celestial spheres, he did not put it at the exact center of the universe, but near it. Copernicus' system used only uniform circular motions, correcting what was seen by many as the chief inelegance in Ptolemy's system.

The Copernican model replaced Ptolemy

's equant

circles with more epicycles. This is the main reason that Copernicus' system had even more epicycles than Ptolemy's. The Copernican system can be summarized in several propositions, as Copernicus himself did in his early Commentariolus

that he handed only to friends probably in the 1510s. The "little commentary" was never printed. Its existence was only known indirectly until a copy was discovered in Stockholm around 1880, and another in Vienna

a few years later.

The major features of Copernican theory are:

, a theologian friend of Copernicus, who urged that the theory, which was considered a tool that allows simpler and more accurate calculations, did not necessarily have implications outside the limited realm of astronomy.

Copernicus' actual book began with a letter from his (by then deceased) friend Nikolaus von Schönberg, Cardinal Archbishop of Capua

, urging Copernicus to publish his theory. Then, in a lengthy introduction, Copernicus dedicated the book to Pope Paul III

, explaining his ostensible motive in writing the book as relating to the inability of earlier astronomers to agree on an adequate theory of the planets, and noting that if his system increased the accuracy of astronomical predictions it would allow the Church to develop a more accurate calendar. At that time, a reform of the Julian Calendar was considered necessary and was one of the major reasons for the Church's interest in astronomy.

The work itself was then divided into six books:

used Copernicus' parameters to produce the Prutenic Tables

. However, these tables translated Copernicus' mathematical methods back into a geocentric system, rejecting heliocentric

cosmology

on physical and theological grounds. The Prutenic tables came to be preferred by Prussian and German astronomers. The degree of improved accuracy of these tables remains an open question, but their usage of Copernican ideas led to more serious consideration of a heliocentric model. However, even forty-five years after the publication of De Revolutionibus, the astronomer Tycho Brahe

went so far as to construct a cosmology precisely equivalent to that of Copernicus, but with the Earth held fixed in the center of the celestial sphere instead of the Sun. It was another generation before a community of practicing astronomers appeared who accepted heliocentric cosmology.

From a modern point of view, the Copernican model has a number of advantages. It accurately predicts the relative distances of the planets from the Sun, although this meant abandoning the cherished Aristotelian idea that there is no empty space between the planetary spheres. Copernicus also gave a clear account of the cause of the seasons: that the Earth's axis is not perpendicular to the plane of its orbit. In addition, Copernicus's theory provided a strikingly simple explanation for the apparent retrograde motions of the planets—namely as parallactic

displacements resulting from the Earth's motion around the Sun—an important consideration in Johannes Kepler

's conviction that the theory was substantially correct.

However, for his contemporaries, the ideas presented by Copernicus were not markedly easier to use than the geocentric theory and did not produce more accurate predictions of planetary positions. Copernicus was aware of this and could not present any observational "proof", relying instead on arguments about what would be a more complete and elegant system. The Copernican model appeared to be contrary to common sense and to contradict the Bible. Tycho Brahe's arguments against Copernicus are illustrative of the physical, theological, and even astronomical grounds on which heliocentric cosmology was rejected. Tycho, arguably the most accomplished astronomer of his time, appreciated the elegance of the Copernican system, but objected to the idea of a moving Earth on the basis of physics, astronomy, and religion. The Aristotelian physics

of the time (modern Newtonian physics was still a century away) offered no physical explanation for the motion of a massive body like Earth, but could easily explain the motion of heavenly bodies by postulating that they were made of a different sort substance called aether

that moved naturally. So Tycho said that the Copernican system “... expertly and completely circumvents all that is superfluous or discordant in the system of Ptolemy. On no point does it offend the principle of mathematics. Yet it ascribes to the Earth, that hulking, lazy body, unfit for motion, a motion as quick as that of the aethereal torches, and a triple motion at that.” Likewise, Tycho took issue with the vast distances to the stars that Copernicus had assumed in order to explain why the Earth's motion produced no visible changes in the appearance of the fixed stars (known as annual stellar parallax

). Tycho had measured the apparent sizes of stars (now known to be illusory – see stellar magnitude

), and used geometry to calculate that in order to both have those apparent sizes and be as far away as heliocentrism required, stars would have to be huge (the size of Earth's orbit or larger, and thus much larger than the sun). Regarding this Tycho wrote, “Deduce these things geometrically if you like, and you will see how many absurdities (not to mention others) accompany this assumption [of the motion of the earth] by inference.” He said his Tychonic system

, which incorporated Copernican features into a geocentric system, “offended neither the principles of physics nor Holy Scripture”. Thus many astronomers accepted some aspects of Copernicus's theory at the expense of others. His model did have a large influence on later scientists such as Galileo

and Johannes Kepler

, who adopted, championed and (especially in Kepler's case) sought to improve it. However, in the years following publication of de Revolutionibus, for leading astronomers such as Erasmus Reinhold, the key attraction of Copernicus's ideas was that they reinstated the idea of uniform circular motion for the planets.

During the 17th century, several further discoveries eventually led to the complete acceptance of heliocentrism:

In 1725, James Bradley

discovered stellar aberration

, an apparent annual motion of stars around small ellipses, and attributed it to the finite speed of light

and the motion of Earth in its orbit around the Sun.

In 1838, Friedrich Bessel

made the first successful measurements of annual parallax for the star 61 Cygni using a heliometer.

In the 20th century, orbits are explained by general relativity

, which can be formulated using any desired coordinate system, and it is no longer necessary to consider the Sun the center of anything.

argued that Copernicus only transferred "some properties to the Sun's many astronomical functions previously attributed to the earth." Other historians have since argued that Kuhn underestimated what was "revolutionary" about Copernicus' work, and emphasized the difficulty Copernicus would have had in putting forward a new astronomical theory relying alone on simplicity in geometry, given that he had no experimental evidence.

In his book The Sleepwalkers: A History of Man's Changing Vision of the Universe

, Arthur Koestler

puts Copernicus in a different light to what many authors seem to suggest, portraying him as a coward who was reluctant to publish his work due to a crippling fear of ridicule.

Nicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus was a Renaissance astronomer and the first person to formulate a comprehensive heliocentric cosmology which displaced the Earth from the center of the universe....

and published in 1543. It positioned the Sun

Sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is almost perfectly spherical and consists of hot plasma interwoven with magnetic fields...

near the center of the Universe

Universe

The Universe is commonly defined as the totality of everything that exists, including all matter and energy, the planets, stars, galaxies, and the contents of intergalactic space. Definitions and usage vary and similar terms include the cosmos, the world and nature...

, motionless, with Earth and the other planets rotating around it in circular paths modified by epicycles and at uniform speeds. The Copernican model departed from the Ptolemaic

Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy , was a Roman citizen of Egypt who wrote in Greek. He was a mathematician, astronomer, geographer, astrologer, and poet of a single epigram in the Greek Anthology. He lived in Egypt under Roman rule, and is believed to have been born in the town of Ptolemais Hermiou in the...

system that prevailed in Western culture

Western culture

Western culture, sometimes equated with Western civilization or European civilization, refers to cultures of European origin and is used very broadly to refer to a heritage of social norms, ethical values, traditional customs, religious beliefs, political systems, and specific artifacts and...

for centuries, placing Earth at the center of the Universe, and is often regarded as the launching point to modern astronomy

Astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that deals with the study of celestial objects and phenomena that originate outside the atmosphere of Earth...

and the Scientific Revolution

Scientific revolution

The Scientific Revolution is an era associated primarily with the 16th and 17th centuries during which new ideas and knowledge in physics, astronomy, biology, medicine and chemistry transformed medieval and ancient views of nature and laid the foundations for modern science...

.

As a university-trained Catholic priest dedicated to astronomy, Copernicus was acquainted with the Sun-centered cosmos of the ancient Greek Aristarchus

Aristarchus of Samos

Aristarchus, or more correctly Aristarchos , was a Greek astronomer and mathematician, born on the island of Samos, in Greece. He presented the first known heliocentric model of the solar system, placing the Sun, not the Earth, at the center of the known universe...

. Although he circulated an outline of the heliocentric theory to colleagues decades earlier, the idea was largely forgotten until late in his life he was urged by a pupil to complete and publish a mathematically detailed account of his model. Copernicus's challenge was to present a practical alternative to the Ptolemaic model by more elegantly and accurately determining the length of a solar year while preserving the metaphysical

Pythagoreanism

Pythagoreanism was the system of esoteric and metaphysical beliefs held by Pythagoras and his followers, the Pythagoreans, who were considerably influenced by mathematics. Pythagoreanism originated in the 5th century BCE and greatly influenced Platonism...

implications of a mathematically ordered cosmos. Thus his heliocentric model retained several of the Ptolemaic elements causing the inaccuracies, such as the planets' circular orbits, epicycles, and uniform speeds, while at the same time re-introducing such innovations as:

-

-

- Earth is one of seven ordered planets in a solar system circling a stationary Sun

- Earth has three motions: daily rotation, annual revolution, and annual tilting of its axis

- Retrograde motion of the planets is explained by Earth's motion

- Distance from Earth to the Sun is small compared to the distance to the stars

-

Earlier theories with the Earth in motion

PhilolausPhilolaus

Philolaus was a Greek Pythagorean and Presocratic philosopher. He argued that all matter is composed of limiting and limitless things, and that the universe is determined by numbers. He is credited with originating the theory that the earth was not the center of the universe.-Life:Philolaus is...

(4th century BC) was also one of the first to hypothesize movement of the Earth, probably inspired by Pythagoras

Pythagoras

Pythagoras of Samos was an Ionian Greek philosopher, mathematician, and founder of the religious movement called Pythagoreanism. Most of the information about Pythagoras was written down centuries after he lived, so very little reliable information is known about him...

' theories about a spherical globe. Aristarchus of Samos

Aristarchus of Samos

Aristarchus, or more correctly Aristarchos , was a Greek astronomer and mathematician, born on the island of Samos, in Greece. He presented the first known heliocentric model of the solar system, placing the Sun, not the Earth, at the center of the known universe...

in the 3rd century BC had developed some theories of Heraclides Ponticus

Heraclides Ponticus

Heraclides Ponticus , also known as Herakleides and Heraklides of Pontus, was a Greek philosopher and astronomer who lived and died at Heraclea Pontica, now Karadeniz Ereğli, Turkey. He is best remembered for proposing that the earth rotates on its axis, from west to east, once every 24 hours...

(speaking of a revolution by Earth on its axis) to propose what was, so far as is known, the first serious model of a heliocentric solar system. His work about a heliocentric system has not survived, so one may only speculate about what led him to his conclusions. It is notable that, according to Plutarch, a contemporary of Aristarchus accused him of impiety for "putting the Earth in motion."

Several Muslim astronomers, such as Ibn al-Haytham, Abu-Rayhan Biruni, Abu Said Sinjari, Najm al-Dīn al-Qazwīnī al-Kātibī

Najm al-Dīn al-Qazwīnī al-Kātibī

Najm al-Dīn al-Qazwīnī al-Kātibī was a Persian Islamic philosopher and logician of the Shafi`i school. A student of Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, he is the author of two major works, one on logic, Al-Risala al-Shamsiyya, and one on metaphysics and the natural sciences, Hikmat al-'Ain.-Logic:His work on...

, and Qutb al-Din al-Shirazi

Qutb al-Din al-Shirazi

Qotb al-Din Shirazi or Qutb al-Din al-Shirazi was a 13th century Persian Muslim polymath and Persian poet who made contributions astronomy, mathematics, medicine, physics, music theory, philosophy and Sufism.- Biography :...

also discussed the possibility of heliocentrism.

Copernicus cited Aristarchus and Philolaus in an early manuscript of his book which survives, stating: "Philolaus believed in the mobility of the earth, and some even say that Aristarchus of Samos was of that opinion." For reasons unknown (although possibly out of reluctance to quote pre-Christian sources), he did not include this passage in the publication of his book. Inspiration came to Copernicus not from observation of the planets, but from reading two authors. In Cicero

Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero , was a Roman philosopher, statesman, lawyer, political theorist, and Roman constitutionalist. He came from a wealthy municipal family of the equestrian order, and is widely considered one of Rome's greatest orators and prose stylists.He introduced the Romans to the chief...

he found an account of the theory of Hicetas

Hicetas

Hicetas was a Greek philosopher of the Pythagorean School. He was born in Syracuse. Like his fellow Pythagorean Ecphantus and the Academic Heraclides Ponticus, he believed that the daily movement of permanent stars was caused by the rotation of the Earth around its axis....

. Plutarch

Plutarch

Plutarch then named, on his becoming a Roman citizen, Lucius Mestrius Plutarchus , c. 46 – 120 AD, was a Greek historian, biographer, essayist, and Middle Platonist known primarily for his Parallel Lives and Moralia...

provided an account of the Pythagoreans Heraclides Ponticus

Heraclides Ponticus

Heraclides Ponticus , also known as Herakleides and Heraklides of Pontus, was a Greek philosopher and astronomer who lived and died at Heraclea Pontica, now Karadeniz Ereğli, Turkey. He is best remembered for proposing that the earth rotates on its axis, from west to east, once every 24 hours...

, Philolaus

Philolaus

Philolaus was a Greek Pythagorean and Presocratic philosopher. He argued that all matter is composed of limiting and limitless things, and that the universe is determined by numbers. He is credited with originating the theory that the earth was not the center of the universe.-Life:Philolaus is...

, and Ecphantes. These authors had proposed a moving Earth, which did not, however, revolve around a central sun. When Copernicus' book was published, it contained an unauthorized preface by the Lutheran theologian Andreas Osiander

Andreas Osiander

Andreas Osiander was a German Lutheran theologian.- Career :Born at Gunzenhausen in Franconia, Osiander studied at the University of Ingolstadt before being ordained as a priest in 1520. In the same year he began work at an Augustinian convent in Nuremberg as a Hebrew tutor. In 1522, he was...

. This cleric stated that Copernicus wrote his heliocentric account of the Earth's movement as a mere mathematical hypothesis, not as an account that contained truth or even probability. Since Copernicus' hypothesis was believed to contradict the Old Testament

Old Testament

The Old Testament, of which Christians hold different views, is a Christian term for the religious writings of ancient Israel held sacred and inspired by Christians which overlaps with the 24-book canon of the Masoretic Text of Judaism...

account of the Sun's movement around the Earth (Joshua

Book of Joshua

The Book of Joshua is the sixth book in the Hebrew Bible and of the Old Testament. Its 24 chapters tell of the entry of the Israelites into Canaan, their conquest and division of the land under the leadership of Joshua, and of serving God in the land....

10:12-13), this was apparently written to soften any religious backlash against the book. However, there is no evidence that Copernicus himself considered the heliocentric model as merely mathematically convenient, separate from reality.

Anticipations of Copernicus's models for planetary orbits

Mathematical techniques developed in the 13th-14th centuries by the Muslim astronomersIslamic astronomy

Islamic astronomy or Arabic astronomy comprises the astronomical developments made in the Islamic world, particularly during the Islamic Golden Age , and mostly written in the Arabic language. These developments mostly took place in the Middle East, Central Asia, Al-Andalus, and North Africa, and...

, Mo'ayyeduddin Urdi

Mo'ayyeduddin Urdi

Mu’ayyad al-Din al-’Urdi was an Kurdish Muslim astronomer, mathematician, architect and engineer working at the Maragheh observatory...

, Nasir al-Din al-Tusi

Nasir al-Din al-Tusi

Khawaja Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad ibn Ḥasan Ṭūsī , better known as Naṣīr al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī , was a Persian polymath and prolific writer: an astronomer, biologist, chemist, mathematician, philosopher, physician, physicist, scientist, theologian and Marja Taqleed...

, and Ibn al-Shatir

Ibn al-Shatir

Ala Al-Din Abu'l-Hasan Ali Ibn Ibrahim Ibn al-Shatir was an Arab Muslim astronomer, mathematician, engineer and inventor who worked as muwaqqit at the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, Syria.-Astronomy:...

for geocentric models of planetary motions closely resemble some of those used later by Copernicus in his heliocentric models. This has led some scholars to argue that Copernicus must have had access to some yet to be identified work on the ideas of those earlier astronomers. However, no likely candidate for this conjectured work has yet come to light, and other scholars have argued that Copernicus could well have developed these ideas independently of the Islamic tradition. Copernicus also discusses the theories of Al-Battani

Al-Battani

Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad ibn Jābir ibn Sinān al-Raqqī al-Ḥarrānī al-Ṣābiʾ al-Battānī was a Muslim astronomer, astrologer, and mathematician...

and Averroes

Averroes

' , better known just as Ibn Rushd , and in European literature as Averroes , was a Muslim polymath; a master of Aristotelian philosophy, Islamic philosophy, Islamic theology, Maliki law and jurisprudence, logic, psychology, politics, Arabic music theory, and the sciences of medicine, astronomy,...

in his major work.

The Ptolemaic system

The prevailing astronomical model of the cosmos in Europe in the 1,400 years leading up to the 16th century was that created by the Roman citizen Claudius Ptolemy in his AlmagestAlmagest

The Almagest is a 2nd-century mathematical and astronomical treatise on the apparent motions of the stars and planetary paths. Written in Greek by Claudius Ptolemy, a Roman era scholar of Egypt,...

, dating from about 150 A.D. Throughout the Middle Ages

Middle Ages

The Middle Ages is a periodization of European history from the 5th century to the 15th century. The Middle Ages follows the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 and precedes the Early Modern Era. It is the middle period of a three-period division of Western history: Classic, Medieval and Modern...

it was spoken of as the authoritative text on astronomy, although its author remained a little understood figure frequently mistaken as one of the Ptolemaic rulers

Ptolemaic dynasty

The Ptolemaic dynasty, was a Macedonian Greek royal family which ruled the Ptolemaic Empire in Egypt during the Hellenistic period. Their rule lasted for 275 years, from 305 BC to 30 BC...

of Egypt. The Ptolemaic system drew on many previous theories that viewed Earth as a stationary center of the universe. Stars were embedded in a large outer sphere which rotated relatively rapidly, while the planets dwelt in smaller spheres between—a separate one for each planet. To account for apparent anomalies in this view, such as the apparent retrograde motion of the planets, a system of deferents and epicycles

Deferent and epicycle

In the Ptolemaic system of astronomy, the epicycle was a geometric model used to explain the variations in speed and direction of the apparent motion of the Moon, Sun, and planets...

was used. The planet was said to revolve in a small circle (the epicycle) about a center, which itself revolved in a larger circle (the deferent) about a center on or near the Earth.

A complementary theory to Ptolemy's employed homocentric spheres: the spheres within which the planets rotated, could themselves rotate somewhat. This theory predated Ptolemy (it was first devised by Eudoxus of Cnidus

Eudoxus of Cnidus

Eudoxus of Cnidus was a Greek astronomer, mathematician, scholar and student of Plato. Since all his own works are lost, our knowledge of him is obtained from secondary sources, such as Aratus's poem on astronomy...

; by the time of Copernicus it was associated with Averroes

Averroes

' , better known just as Ibn Rushd , and in European literature as Averroes , was a Muslim polymath; a master of Aristotelian philosophy, Islamic philosophy, Islamic theology, Maliki law and jurisprudence, logic, psychology, politics, Arabic music theory, and the sciences of medicine, astronomy,...

). Also popular with astronomers were variations such as eccentrics

Eccentricity (mathematics)

In mathematics, the eccentricity, denoted e or \varepsilon, is a parameter associated with every conic section. It can be thought of as a measure of how much the conic section deviates from being circular.In particular,...

—by which the rotational axis was offset and not completely at the center.

Ptolemy's unique contribution to this theory was the equant

Equant

Equant is a mathematical concept developed by Claudius Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD to account for the observed motion of heavenly bodies....

—a point about which the center of a planet's epicycle moved with uniform angular velocity, but which was offset from the center of its deferent. This violated one of the fundamental principles of Aristotelian cosmology—namely, that the motions of the planets should be explained in terms of uniform circular motion, and was considered a serious defect by many medieval astronomers. In Copernicus's day, the most up-to-date version of the Ptolemaic system was that of Peurbach (1423–1461) and Regiomontanus

Regiomontanus

Johannes Müller von Königsberg , today best known by his Latin toponym Regiomontanus, was a German mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, translator and instrument maker....

(1436–1476).

Copernican theory

De revolutionibus orbium coelestium

De revolutionibus orbium coelestium is the seminal work on the heliocentric theory of the Renaissance astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus...

- On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres (first edition 1543 in Nuremberg, second edition 1566 in Basel

Basel

Basel or Basle In the national languages of Switzerland the city is also known as Bâle , Basilea and Basilea is Switzerland's third most populous city with about 166,000 inhabitants. Located where the Swiss, French and German borders meet, Basel also has suburbs in France and Germany...

), was published during the year of his death, though he had arrived at his theory several decades earlier. The book marks the beginning of the shift away from a geocentric (and anthropocentric

Anthropocentrism

Anthropocentrism describes the tendency for human beings to regard themselves as the central and most significant entities in the universe, or the assessment of reality through an exclusively human perspective....

) universe with the Earth at its center. Copernicus held that the Earth is another planet

Planet

A planet is a celestial body orbiting a star or stellar remnant that is massive enough to be rounded by its own gravity, is not massive enough to cause thermonuclear fusion, and has cleared its neighbouring region of planetesimals.The term planet is ancient, with ties to history, science,...

revolving around the fixed sun once a year, and turning on its axis once a day. But while Copernicus put the Sun at the center of the celestial spheres, he did not put it at the exact center of the universe, but near it. Copernicus' system used only uniform circular motions, correcting what was seen by many as the chief inelegance in Ptolemy's system.

The Copernican model replaced Ptolemy

Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy , was a Roman citizen of Egypt who wrote in Greek. He was a mathematician, astronomer, geographer, astrologer, and poet of a single epigram in the Greek Anthology. He lived in Egypt under Roman rule, and is believed to have been born in the town of Ptolemais Hermiou in the...

's equant

Equant

Equant is a mathematical concept developed by Claudius Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD to account for the observed motion of heavenly bodies....

circles with more epicycles. This is the main reason that Copernicus' system had even more epicycles than Ptolemy's. The Copernican system can be summarized in several propositions, as Copernicus himself did in his early Commentariolus

Commentariolus

The "Commentariolus" is Nicolaus Copernicus's forty-page outline of an early version of his revolutionary heliocentric theory of the universe...

that he handed only to friends probably in the 1510s. The "little commentary" was never printed. Its existence was only known indirectly until a copy was discovered in Stockholm around 1880, and another in Vienna

Vienna

Vienna is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Austria and one of the nine states of Austria. Vienna is Austria's primary city, with a population of about 1.723 million , and is by far the largest city in Austria, as well as its cultural, economic, and political centre...

a few years later.

The major features of Copernican theory are:

- Heavenly motions are uniform, eternal, and circular or compounded of several circles (epicycles).

- The center of the universe is near the Sun.

- Around the Sun, in order, are Mercury, Venus, Earth and Moon, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, and the fixed stars.

- The Earth has three motions: daily rotation, annual revolution, and annual tilting of its axis.

- Retrograde motion of the planets is explained by the Earth's motion.

- The distance from the Earth to the Sun is small compared to the distance to the stars.

De revolutionibus orbium coelestium

It opened with an originally anonymous preface by Andreas OsianderAndreas Osiander

Andreas Osiander was a German Lutheran theologian.- Career :Born at Gunzenhausen in Franconia, Osiander studied at the University of Ingolstadt before being ordained as a priest in 1520. In the same year he began work at an Augustinian convent in Nuremberg as a Hebrew tutor. In 1522, he was...

, a theologian friend of Copernicus, who urged that the theory, which was considered a tool that allows simpler and more accurate calculations, did not necessarily have implications outside the limited realm of astronomy.

Copernicus' actual book began with a letter from his (by then deceased) friend Nikolaus von Schönberg, Cardinal Archbishop of Capua

Capua

Capua is a city and comune in the province of Caserta, Campania, southern Italy, situated 25 km north of Naples, on the northeastern edge of the Campanian plain. Ancient Capua was situated where Santa Maria Capua Vetere is now...

, urging Copernicus to publish his theory. Then, in a lengthy introduction, Copernicus dedicated the book to Pope Paul III

Pope Paul III

Pope Paul III , born Alessandro Farnese, was Pope of the Roman Catholic Church from 1534 to his death in 1549. He came to the papal throne in an era following the sack of Rome in 1527 and rife with uncertainties in the Catholic Church following the Protestant Reformation...

, explaining his ostensible motive in writing the book as relating to the inability of earlier astronomers to agree on an adequate theory of the planets, and noting that if his system increased the accuracy of astronomical predictions it would allow the Church to develop a more accurate calendar. At that time, a reform of the Julian Calendar was considered necessary and was one of the major reasons for the Church's interest in astronomy.

The work itself was then divided into six books:

- General vision of the heliocentric theory, and a summarized exposition of his idea of the World.

- Mainly theoretical, presents the principles of spherical astronomy and a list of stars (as a basis for the arguments developed in the subsequent books).

- Mainly dedicated to the apparent motions of the Sun and to related phenomena.

- Description of the Moon and its orbital motions.

- Concrete exposition of the new system including planetary longitude.

- Further concrete exposition of the new system Including planetary latitude.

Acceptance of Copernican heliocentrism

From publication until about 1700, few astronomers were convinced by the Copernican system, though the book was relatively widely circulated (around 500 copies of the first and second editions have survived, which is a large number by the scientific standards of the time). Few of Copernicus' contemporaries were ready to concede that the Earth actually moved, although Erasmus ReinholdErasmus Reinhold

Erasmus Reinhold was a German astronomer and mathematician, considered to be the most influential astronomical pedagogue of his generation. He was born and died in Saalfeld, Saxony....

used Copernicus' parameters to produce the Prutenic Tables

Prutenic Tables

The Prutenic Tables , were an ephemeris by the astronomer Erasmus Reinhold published in 1551. They are sometimes called the Prussian Tables after Albert I, Duke of Prussia, who supported Reinhold and financed the printing...

. However, these tables translated Copernicus' mathematical methods back into a geocentric system, rejecting heliocentric

Heliocentrism

Heliocentrism, or heliocentricism, is the astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around a stationary Sun at the center of the universe. The word comes from the Greek . Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to geocentrism, which placed the Earth at the center...

cosmology

Cosmology

Cosmology is the discipline that deals with the nature of the Universe as a whole. Cosmologists seek to understand the origin, evolution, structure, and ultimate fate of the Universe at large, as well as the natural laws that keep it in order...

on physical and theological grounds. The Prutenic tables came to be preferred by Prussian and German astronomers. The degree of improved accuracy of these tables remains an open question, but their usage of Copernican ideas led to more serious consideration of a heliocentric model. However, even forty-five years after the publication of De Revolutionibus, the astronomer Tycho Brahe

Tycho Brahe

Tycho Brahe , born Tyge Ottesen Brahe, was a Danish nobleman known for his accurate and comprehensive astronomical and planetary observations...

went so far as to construct a cosmology precisely equivalent to that of Copernicus, but with the Earth held fixed in the center of the celestial sphere instead of the Sun. It was another generation before a community of practicing astronomers appeared who accepted heliocentric cosmology.

From a modern point of view, the Copernican model has a number of advantages. It accurately predicts the relative distances of the planets from the Sun, although this meant abandoning the cherished Aristotelian idea that there is no empty space between the planetary spheres. Copernicus also gave a clear account of the cause of the seasons: that the Earth's axis is not perpendicular to the plane of its orbit. In addition, Copernicus's theory provided a strikingly simple explanation for the apparent retrograde motions of the planets—namely as parallactic

Parallax

Parallax is a displacement or difference in the apparent position of an object viewed along two different lines of sight, and is measured by the angle or semi-angle of inclination between those two lines. The term is derived from the Greek παράλλαξις , meaning "alteration"...

displacements resulting from the Earth's motion around the Sun—an important consideration in Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler was a German mathematician, astronomer and astrologer. A key figure in the 17th century scientific revolution, he is best known for his eponymous laws of planetary motion, codified by later astronomers, based on his works Astronomia nova, Harmonices Mundi, and Epitome of Copernican...

's conviction that the theory was substantially correct.

However, for his contemporaries, the ideas presented by Copernicus were not markedly easier to use than the geocentric theory and did not produce more accurate predictions of planetary positions. Copernicus was aware of this and could not present any observational "proof", relying instead on arguments about what would be a more complete and elegant system. The Copernican model appeared to be contrary to common sense and to contradict the Bible. Tycho Brahe's arguments against Copernicus are illustrative of the physical, theological, and even astronomical grounds on which heliocentric cosmology was rejected. Tycho, arguably the most accomplished astronomer of his time, appreciated the elegance of the Copernican system, but objected to the idea of a moving Earth on the basis of physics, astronomy, and religion. The Aristotelian physics

Aristotelian physics

Aristotelian Physics the natural sciences, are described in the works of the Greek philosopher Aristotle . In the Physics, Aristotle established general principles of change that govern all natural bodies; both living and inanimate, celestial and terrestrial—including all motion, change in respect...

of the time (modern Newtonian physics was still a century away) offered no physical explanation for the motion of a massive body like Earth, but could easily explain the motion of heavenly bodies by postulating that they were made of a different sort substance called aether

Aether (classical element)

According to ancient and medieval science aether , also spelled æther or ether, is the material that fills the region of the universe above the terrestrial sphere.-Mythological origins:...

that moved naturally. So Tycho said that the Copernican system “... expertly and completely circumvents all that is superfluous or discordant in the system of Ptolemy. On no point does it offend the principle of mathematics. Yet it ascribes to the Earth, that hulking, lazy body, unfit for motion, a motion as quick as that of the aethereal torches, and a triple motion at that.” Likewise, Tycho took issue with the vast distances to the stars that Copernicus had assumed in order to explain why the Earth's motion produced no visible changes in the appearance of the fixed stars (known as annual stellar parallax

Stellar parallax

Stellar parallax is the effect of parallax on distant stars in astronomy. It is parallax on an interstellar scale, and it can be used to determine the distance of Earth to another star directly with accurate astrometry...

). Tycho had measured the apparent sizes of stars (now known to be illusory – see stellar magnitude

Magnitude (astronomy)

Magnitude is the logarithmic measure of the brightness of an object, in astronomy, measured in a specific wavelength or passband, usually in optical or near-infrared wavelengths.-Background:...

), and used geometry to calculate that in order to both have those apparent sizes and be as far away as heliocentrism required, stars would have to be huge (the size of Earth's orbit or larger, and thus much larger than the sun). Regarding this Tycho wrote, “Deduce these things geometrically if you like, and you will see how many absurdities (not to mention others) accompany this assumption [of the motion of the earth] by inference.” He said his Tychonic system

Tychonic system

The Tychonic system was a model of the solar system published by Tycho Brahe in the late 16th century which combined what he saw as the mathematical benefits of the Copernican system with the philosophical and "physical" benefits of the Ptolemaic system...

, which incorporated Copernican features into a geocentric system, “offended neither the principles of physics nor Holy Scripture”. Thus many astronomers accepted some aspects of Copernicus's theory at the expense of others. His model did have a large influence on later scientists such as Galileo

Galileo Galilei

Galileo Galilei , was an Italian physicist, mathematician, astronomer, and philosopher who played a major role in the Scientific Revolution. His achievements include improvements to the telescope and consequent astronomical observations and support for Copernicanism...

and Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler was a German mathematician, astronomer and astrologer. A key figure in the 17th century scientific revolution, he is best known for his eponymous laws of planetary motion, codified by later astronomers, based on his works Astronomia nova, Harmonices Mundi, and Epitome of Copernican...

, who adopted, championed and (especially in Kepler's case) sought to improve it. However, in the years following publication of de Revolutionibus, for leading astronomers such as Erasmus Reinhold, the key attraction of Copernicus's ideas was that they reinstated the idea of uniform circular motion for the planets.

During the 17th century, several further discoveries eventually led to the complete acceptance of heliocentrism:

- Using the newly-invented telescopeTelescopeA telescope is an instrument that aids in the observation of remote objects by collecting electromagnetic radiation . The first known practical telescopes were invented in the Netherlands at the beginning of the 1600s , using glass lenses...

, Galileo discovered the four large moons of Jupiter (evidence that the solar system contained bodies that did not orbit Earth), the phases of Venus (the first observational evidence for Copernicus' theory) and the rotation of the Sun about a fixed axis as indicated by the apparent annual variation in the motion of sunspots; - With a telescope, Giovanni Zupi saw the phases of Mercury in 1639;

- Kepler introduced the idea that the orbits of the planets were elliptical rather than circular.

- Isaac NewtonIsaac NewtonSir Isaac Newton PRS was an English physicist, mathematician, astronomer, natural philosopher, alchemist, and theologian, who has been "considered by many to be the greatest and most influential scientist who ever lived."...

proposed universal gravityNewton's law of universal gravitationNewton's law of universal gravitation states that every point mass in the universe attracts every other point mass with a force that is directly proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them...

and the inverse-square lawInverse-square lawIn physics, an inverse-square law is any physical law stating that a specified physical quantity or strength is inversely proportional to the square of the distance from the source of that physical quantity....

of gravitational attraction to explain Kepler's elliptical planetary orbits.

In 1725, James Bradley

James Bradley

James Bradley FRS was an English astronomer and served as Astronomer Royal from 1742, succeeding Edmund Halley. He is best known for two fundamental discoveries in astronomy, the aberration of light , and the nutation of the Earth's axis...

discovered stellar aberration

Aberration of light

The aberration of light is an astronomical phenomenon which produces an apparent motion of celestial objects about their real locations...

, an apparent annual motion of stars around small ellipses, and attributed it to the finite speed of light

Speed of light

The speed of light in vacuum, usually denoted by c, is a physical constant important in many areas of physics. Its value is 299,792,458 metres per second, a figure that is exact since the length of the metre is defined from this constant and the international standard for time...

and the motion of Earth in its orbit around the Sun.

In 1838, Friedrich Bessel

Friedrich Bessel

-References:* John Frederick William Herschel, A brief notice of the life, researches, and discoveries of Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel, London: Barclay, 1847 -External links:...

made the first successful measurements of annual parallax for the star 61 Cygni using a heliometer.

In the 20th century, orbits are explained by general relativity

General relativity

General relativity or the general theory of relativity is the geometric theory of gravitation published by Albert Einstein in 1916. It is the current description of gravitation in modern physics...

, which can be formulated using any desired coordinate system, and it is no longer necessary to consider the Sun the center of anything.

Modern opinion

Whether Copernicus' propositions were "revolutionary" or "conservative" was a topic of debate in the late twentieth century. Thomas KuhnThomas Kuhn

Thomas Samuel Kuhn was an American historian and philosopher of science whose controversial 1962 book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions was deeply influential in both academic and popular circles, introducing the term "paradigm shift," which has since become an English-language staple.Kuhn...

argued that Copernicus only transferred "some properties to the Sun's many astronomical functions previously attributed to the earth." Other historians have since argued that Kuhn underestimated what was "revolutionary" about Copernicus' work, and emphasized the difficulty Copernicus would have had in putting forward a new astronomical theory relying alone on simplicity in geometry, given that he had no experimental evidence.

In his book The Sleepwalkers: A History of Man's Changing Vision of the Universe

The Sleepwalkers

The Sleepwalkers: A History of Man's Changing Vision of the Universe is a 1959 book by Arthur Koestler, and one of the main accounts of the history of cosmology and astronomy in the Western World, beginning in ancient Mesopotamia and ending with Isaac Newton. The book challenges the habitual idea...

, Arthur Koestler

Arthur Koestler

Arthur Koestler CBE was a Hungarian author and journalist. Koestler was born in Budapest and, apart from his early school years, was educated in Austria...

puts Copernicus in a different light to what many authors seem to suggest, portraying him as a coward who was reluctant to publish his work due to a crippling fear of ridicule.

External links

- Elementary analysis of planetary orbits from educational website From Stargazers to Starships