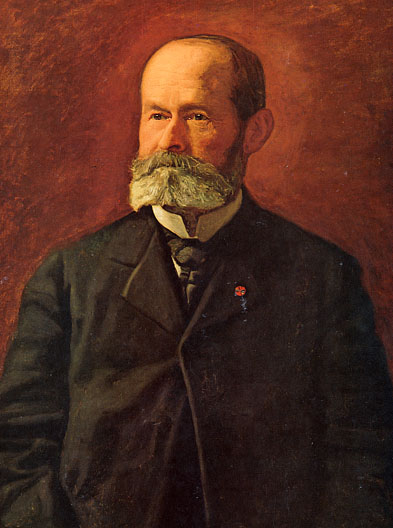

Daniel Garrison Brinton

Encyclopedia

Biography

Brinton was born in Thornbury Township, Chester County, PennsylvaniaThornbury Township, Chester County, Pennsylvania

Thornbury Township is a township in Chester County, Pennsylvania, United States. The population was 3,017 at the 2010 census. It is adjacent to, and was once joined with Thornbury Township, Delaware County, Pennsylvania.-History:...

. After graduating from Yale University

Yale University

Yale University is a private, Ivy League university located in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701 in the Colony of Connecticut, the university is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States...

in 1858, Brinton studied at Jefferson Medical College for two years and spent the next travelling in Europe. He continued his studies at Paris

Paris

Paris is the capital and largest city in France, situated on the river Seine, in northern France, at the heart of the Île-de-France region...

and Heidelberg

Heidelberg

-Early history:Between 600,000 and 200,000 years ago, "Heidelberg Man" died at nearby Mauer. His jaw bone was discovered in 1907; with scientific dating, his remains were determined to be the earliest evidence of human life in Europe. In the 5th century BC, a Celtic fortress of refuge and place of...

. From 1862 to 1865, during the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

, he was a surgeon in the Union army, acting during 1864-1865 as surgeon-in-charge of the U.S. Army general hospital at Quincy, Illinois

Quincy, Illinois

Quincy, known as Illinois' "Gem City," is a river city along the Mississippi River and the county seat of Adams County. As of the 2010 census the city held a population of 40,633. The city anchors its own micropolitan area and is the economic and regional hub of West-central Illinois, catering a...

. Brinton was sun-stroked

Hyperthermia

Hyperthermia is an elevated body temperature due to failed thermoregulation. Hyperthermia occurs when the body produces or absorbs more heat than it can dissipate...

at Missionary Ridge

Missionary Ridge

Missionary Ridge is a geographic feature in Chattanooga, Tennessee, site of the Battle of Missionary Ridge, a battle in the American Civil War, fought on November 25, 1863. Union forces under Maj. Gens. Ulysses S. Grant, William T. Sherman, and George H...

(Third Battle of Chattanooga) and was never again able to travel in very hot weathers. This handicap affected his career as an ethnologist.

After the war, Brinton practiced medicine in West Chester, Pennsylvania

West Chester, Pennsylvania

The Borough of West Chester is the county seat of Chester County, Pennsylvania, United States. The population was 18,461 at the 2010 census.Valley Forge, the Brandywine Battlefield, Longwood Gardens, Marsh Creek State Park, and other historical attractions are near West Chester...

for several years; was the editor of a weekly periodical, the Medical and Surgical Reporter, in Philadelphia from 1874 to 1887; became professor of ethnology and archaeology in the Academy of Natural Sciences

Academy of Natural Sciences

The Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, formerly Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, is the oldest natural science research institution and museum in the New World...

in Philadelphia in 1884; and was professor of American linguistics

Linguistics

Linguistics is the scientific study of human language. Linguistics can be broadly broken into three categories or subfields of study: language form, language meaning, and language in context....

and archaeology in the University of Pennsylvania

University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania is a private, Ivy League university located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States. Penn is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States,Penn is the fourth-oldest using the founding dates claimed by each institution...

from 1886 until his death.

He was a member of numerous learned societies in the United States and in Europe and was president at different times of the Numismatic and Antiquarian

Antiquarian

An antiquarian or antiquary is an aficionado or student of antiquities or things of the past. More specifically, the term is used for those who study history with particular attention to ancient objects of art or science, archaeological and historic sites, or historic archives and manuscripts...

Society of Philadelphia, of the American Folklore Society

American Folklore Society

The American Folklore Society is the US-based professional association for folklorists, with members from the US, Canada, and around the world. It was founded in 1888 by William Wells Newell, who stood at the center of a diverse group of university-based scholars, museum anthropologists, and men...

, the American Philosophical Society

American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society, founded in 1743, and located in Philadelphia, Pa., is an eminent scholarly organization of international reputation, that promotes useful knowledge in the sciences and humanities through excellence in scholarly research, professional meetings, publications,...

, and of the American Association for the Advancement of Science

American Association for the Advancement of Science

The American Association for the Advancement of Science is an international non-profit organization with the stated goals of promoting cooperation among scientists, defending scientific freedom, encouraging scientific responsibility, and supporting scientific education and science outreach for the...

.

At his presidential address to the American Association for the Advancement of Science in August 1895, Brinton advocated theories of scientific racism

Scientific racism

Scientific racism is the use of scientific techniques and hypotheses to sanction the belief in racial superiority or racism.This is not the same as using scientific findings and the scientific method to investigate differences among the humans and argue that there are races...

that were pervasive at that time. As Charles A. Lofgren notes in his book, The Plessy Case

Plessy v. Ferguson

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 , is a landmark United States Supreme Court decision in the jurisprudence of the United States, upholding the constitutionality of state laws requiring racial segregation in private businesses , under the doctrine of "separate but equal".The decision was handed...

, although Brinton "accepted the 'psychical unity' throughout the human species," he claimed "all races were 'not equally endowed,' which disqualified [some of] them from the atmosphere of modern enlightenment." He asserted some have "...an inborn tendency, constitutionally recreant to the codes of civilization, and therefore technically criminal." Further, he said the characteristics of "races, nations, tribes...supply the only sure foundations for legislation, not a priori notions of the rights of man."

Brinton was an anarchist

Anarchism

Anarchism is generally defined as the political philosophy which holds the state to be undesirable, unnecessary, and harmful, or alternatively as opposing authority in the conduct of human relations...

during his last several years of life. In April 1896, he addressed the Ethical Fellowship of Philadelphia with a lecture on "What the Anarchists Want," to a friendly audience. In October 1897, Brinton had dinner with Peter Kropotkin

Peter Kropotkin

Prince Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin was a Russian zoologist, evolutionary theorist, philosopher, economist, geographer, author and one of the world's foremost anarcho-communists. Kropotkin advocated a communist society free from central government and based on voluntary associations between...

after the famous anarchist's only speaking engagement at Philadelphia. Kropotkin had refused invitations from all of the city's elites.

On the occasion of his memorial meeting on October 6, 1900, the keynote speaker Albert H. Smyth stated: "In Europe and America, he sought the society of anarchists and mingled sometimes with the malcontents of the world that he might appreciate their grievances, and weigh their propositions for reform and change."

Works

From 1868 to 1899, Brinton wrote many books, and a large number of pamphlets, brochures, addresses and magazine articles.His works include:

- A study in the native religions of the western continent.

- Library of Aboriginal American Literature. No. VIII

- american authors and their productions

- Nagualism, A Study in Native American Folk-lore and History (1894)

- Ancient nahuatl poetry

- The Myths of the New World (1868), an attempt to analyse and correlate, scientifically, the mythology of the American Indians

- The Religious Sentiment: its Sources and Aim: A Contribution to the Science and Philosophy of Religion (1876)

- American Hero Myths (1882)

- The Annals of the Cakchiquels (1885)

- The Lenâpé and their Legends: With the Complete Text and Symbols of the Walam Olum (1885)

- Essays of an Americanist (1890)

- Races and Peoples: lectures on the science of ethnography (1890);

- The American Race (1891)

- The Pursuit of Happiness (1893)

- Religions of Primitive People (1897)

In addition, he edited and published a Library of American Aboriginal Literature (8 vols. 1882-1890), a valuable contribution to the science of anthropology

Anthropology

Anthropology is the study of humanity. It has origins in the humanities, the natural sciences, and the social sciences. The term "anthropology" is from the Greek anthrōpos , "man", understood to mean mankind or humanity, and -logia , "discourse" or "study", and was first used in 1501 by German...

in America. Of the eight volumes; six were edited by Brinton himself, one by Horatio Hale

Horatio Hale

Horatio Emmons Hale was an American-Canadian ethnologist, philologist and businessman who studied language as a key for classifying ancient peoples and being able to trace their migrations...

and one by Albert Samuel Gatschet

Albert Samuel Gatschet

Albert Samuel Gatschet was a Swiss-American ethnologist who trained as a linguist in Europe but worked most of his career in the United States, where he studied Native American languages and cultures.-Early life and education:Albert Samuel Gatschet was born in Beatenberg, Switzerland...

. His 1885 work is notable for its role in the Walam Olum

Walam Olum

The Walam Olum or Walum Olum, usually translated as "Red Record" or "Red Score," is purportedly a historical narrative of the Lenape Native American tribe. The document has provoked controversy as to its authenticity since its publication in the 1830s by botanist and antiquarian Constantine Samuel...

controversy.