Demographics of Finland

Encyclopedia

This article is about the demographic

features of the population

of Finland

, including population density

, ethnicity

, education level, health of the populace, economic status, religious affiliations and other aspects of the population.

Finland

numbers some 5.4 million and has an average population density of 17 inhabitants per square kilometre. This makes it the third most sparsely populated country in Europe

, after Iceland

and Norway

. Population distribution is very uneven: the population is concentrated on the small southwestern coastal plain. About 64% live in towns and cities, with one million living in the Helsinki Metropolitan Area alone. In Arctic Lapland, on the other hand, there are only 2 people to every square kilometre.

The country is ethnically homogeneous, the dominant ethnicity being Finnish people. The official languages are Finnish

and Swedish

, the latter being the native language of about five per cent of the Finnish population. From the 13th to the early 19th century Finland was a part of the Kingdom of Sweden. The Swedish-speakers are known as Swedish-speaking Finns (finlandssvenskar in Swedish, suomenruotsalaiset in Finnish).

With 79 percent of Finns in its congregation, the Lutheran Church is the largest in the country.

The earliest inhabitants of most of the land area that makes up today's Finland and Scandinavia were in all likehood hunter-gatherers whose closest successors in modern terms would probably be the Sami people

(formerly known as the Lapps). There are 4,500 of them living in Finland today and they are recognised as a minority and speak three distinct languages: Northern Sami

, Inari Sami

and Skolt Sami

. They have been living north of the Arctic Circle

for more than 7,000 years now, but today are a 5% minority in their native Lapland Province. During the late 19th and 20th century there was significant emigration

, particularly from rural areas to Sweden

and North America

, while most immigrants into Finland itself come from other European countries.

Total population

Total population

The overwhelming majority of Finns did marry, however. About 90 percent of the women had been married by the age of forty, and spinsterhood was rare. A shortage of women in rural regions, however, meant that some farmers were forced into bachelorhood.

While the number of marriages was declining, divorce became more common, increasing 250 percent between 1950 and 1980. In 1952 there were 3,500 divorces. The 1960s saw a steady increase in this rate, which averaged about 5,000 divorces a year. A high of 10,191 was reached in 1979; afterwards the divorce rate stabilized at about 9,500 per year during the first half of the 1980s.

A number of factors caused the increased frequency of divorce. One was that an increasingly secularized society viewed marriage, more often than before, as an arrangement that could be ended if it did not satisfy its partners. Another reason was that a gradually expanding welfare system could manage an ever greater portion of the family's traditional tasks, and it made couples less dependent on the institution of marriage. Government provisions for parental leave, child allowances, child care programs, and much improved health and pension plans meant that the family was no longer essential for the care of children and aged relatives. A further cause for weakened family and marital ties was seen in the unsettling effects of the Great Migration and in the economic transformation Finland experienced during the 1960s and the 1970s. The rupture of established social patterns brought uncertainty and an increased potential for conflict into personal relationships.

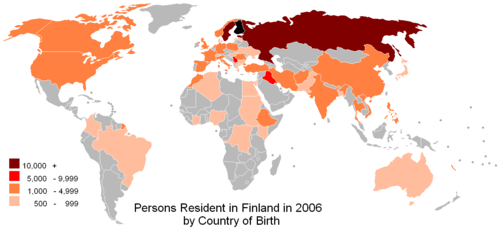

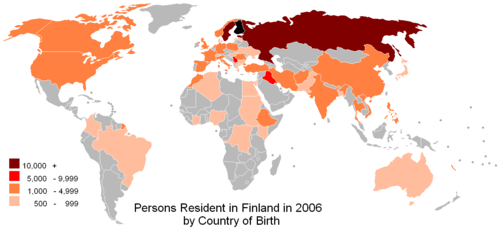

Demographic movement in Finland did not end with the appearance of immigrants from Sweden in the Middle Ages. Finns who left to work in Swedish mines in the sixteenth century began a national tradition, which continued up through the 1970s, of settling in their neighboring country. During the period of tsarist rule, some 100,000 Finns went to Russia, mainly to the St. Petersburg area. Emigration on a large scale began in the second half of the nineteenth century when Finns, along with millions of other Europeans, set out for the United States and Canada. By 1980 Finland had lost an estimated 400,000 of its citizens to these two countries.

Demographic movement in Finland did not end with the appearance of immigrants from Sweden in the Middle Ages. Finns who left to work in Swedish mines in the sixteenth century began a national tradition, which continued up through the 1970s, of settling in their neighboring country. During the period of tsarist rule, some 100,000 Finns went to Russia, mainly to the St. Petersburg area. Emigration on a large scale began in the second half of the nineteenth century when Finns, along with millions of other Europeans, set out for the United States and Canada. By 1980 Finland had lost an estimated 400,000 of its citizens to these two countries.

A great number of Finns emigrated to Sweden after World War II, drawn by that country's prosperity and proximity. Emigration began slowly, but, during the 1960s and the second half of the 1970s, tens of thousands left each year for their western neighbor. The peak emigration year was 1970, when 41,000 Finns settled in Sweden, which caused Finland's population actually to fall that year. Because many of the migrants later returned to Finland, definite figures cannot be calculated, but all told, an estimated 250,000 to 300,000 Finns became permanent residents of Sweden in the postwar period. The overall youthfulness of these emigrants meant that the quality of the work force available to Finnish employers was diminished and that the national birth rate slowed. At one point, every eighth Finnish child was born in Sweden. Finland's Swedish-speaking minority was hard hit by this westward migration; its numbers dropped from 350,000 to about 300,000 between 1950 and 1980. By the 1980s, a strong Finnish economy had brought an end to large-scale migration to Sweden. In fact, the overall population flow was reversed because each year several thousand more Finns returned from Sweden than left for it.

Postwar internal migration began with the resettlement within Finland of virtually all the inhabitants of the parts of Karelia ceded to the Soviet Union. Somewhat more than 400,000 persons, more than 10 percent of the nation's population, found new homes elsewhere in Finland, often in the less settled regions of the east and the north. In these regions, new land, which they cleared for farming, was provided for the refugees; in more populated areas, property was requisitioned. The sudden influx of these settlers was successfully dealt with in just a few years. One of the effects of rural resettlement was an increase in the number of farms during the postwar years, a unique occurrence for industrialized nations of this period.

It was, however, the postwar economic transformation that caused an even larger movement of people within Finland, a movement known to Finns as the Great Migration. It was a massive population shift from rural areas, especially those of eastern and northeastern Finland, to the urban, industrialized south). People left rural regions because the mechanization of agriculture and the forestry industry had eliminated jobs. The displaced work force went to areas where employment in the expanding industrial and service sectors was available. This movement began in the 1950s, but it was most intense during the 1960s and the first half of the 1970s, assuming proportions that in relative terms were unprecedented for a country outside the Third World. The Great Migration left behind rural areas of abandoned farms with reduced and aging populations, and it allowed the creation of a densely populated postindustrial society in the country's south.

The extent of the demographic shift to the south can be shown by the following figures. Between 1951 and 1975, the population registered an increase of 655,000. During this period, the small province of Uusimaa increased its population by 412,000, growing from 670,000 to 1,092,00; three-quarters of this growth was caused by settlers from other provinces. The population increase experienced by four other southern provinces, the Aland Islands, Turku ja Pori, Hame, and Kymi, taken together with that of Uusimaa amounted to 97 percent of the country's total population increase for these years. The population increase of the central and the northern provinces accounted for the remaining 3 percent. Provinces that experienced an actual population loss during these years were in the east and the northeast-Pohjois-Karjala, Mikkeli, and Kuopio.

One way of visualizing the shift to the south would be to draw a line, bowing slightly to the north, between the port cities of Kotka on the Gulf of Finland and Kaskinen on the Gulf of Bothnia. In 1975 the territory to the south of this line would have contained half of Finland's population. Ten years earlier, such a line, drawn farther to the north to mark off perhaps 20 percent more area, would have encompassed half the population. One hundred years earlier, half the population would have been distributed throughout more than twice as much territory. Another indication of the extent to which Finns were located in the south was that by 1980, approximately 90 percent of them lived in the southernmost 41 percent of Finland.

The Finnish and Swedish languages are defined as languages of the state. Additionally, Swedish is an official municipal language in municipalities with significant Swedish-speaking populations. The three Sami languages (North Sami, Inari Sami

, Skolt Sami

) are official in certain municipalities of Lapland.

Finnish people — Finns — speak the Finnish language

, which the dominant language and is spoken almost everywhere in the country. Native Finnish speakers are otherwise recognized as an ethnicity.

Population of mainland Finland (excluding Aland) according to language, 1990-2010 http://pxweb2.stat.fi/Dialog/varval.asp?ma=030_vaerak_tau_102_en&ti=Language+according+to+age+and+gender+by+region+1990+%2D+2010&path=../Database/StatFin/vrm/vaerak/&lang=1&multilang=en

The classification of the Swedish-speakers as an ethnicity is controversial. The government only considers the "working language", Finnish or Swedish, of the person, and "bilinguality" has no official standing. Significant populations of Swedish-speakers are found in coastal areas, from Ostrobothnia to the southern coast, and in the archipelago of Åland. Coastal cities, however, are majority Finnish-speaking, with a few small towns as exceptions. There are very few Swedish-speakers in the inland.

About 90 percent of Finland's 4,400 Sami lived in the municipalities of Enontekiö, Inari, and Utsjoki, and in the reindeer herding-area of Sodankyla. According to Finnish regulations, anyone who spoke the Lapp language, Sami, or who had a relative who was a Lapp, was registered as a Lapp in census records. Finnish Sami spoke three Sami dialects, but by the late 1980s perhaps only a minority actually had Sami as their first language. Lapp children had the right to instruction in Sami, but there were few qualified instructors or textbooks available. One reason for the scarcity of written material in Sami is that the three dialects spoken in Finland made agreement about a common orthography difficult. Perhaps these shortcomings explained why a 1979 study found the educational level of Sami to be considerably lower than that of other Finns.

Few Finnish Sami actually led the traditional nomadic life pictured in school geography texts and in travel brochures. Although many Sami living in rural regions of Lapland earned some of their livelihood from reindeer herding, it was estimated that Sami owned no more than one-third of Finland's 200,000 reindeer. Only 5 percent of Finnish Sami had the herds of 250 to 300 reindeer needed to live entirely from this kind of work. Most Sami worked at more routine activities, including farming, construction, and service industries such as tourism. Often a variety of jobs and sources of income supported Lapp families, which were, on the average, twice the size of a typical Finnish family. Sami also were aided by old-age pensions and by government welfare, which provided a greater share of their income than it did for Finns as a whole.

There have been many efforts over the years by Finnish authorities to safeguard the Sami' culture and way of life and to ease their entry into modern society. Officials created bodies that dealt with the Lapp minority, or formed committees that studied their situation. An early body was the Society for the Promotion of Lapp Culture, formed in 1932. In 1960 the government created the Advisory Commission on Lapp Affairs. The Sami themselves formed the Samii Litto in 1945 and the Johti Sabmelazzat, a more aggressive organization, in 1968. In 1973 the government arranged for elections every four years to a twentymember Sami Parlamenta that was to advise authorities. On the international level, there was the Nordic Sami Council of 1956, and there has been a regularly occurring regional conference since then that represented--in addition to Finland's Sami-- Norway's 20,000 Sami, Sweden's 10,000 Sami, and the 1,000 to 2,000 Sami who remained in the Kola Peninsula in Russia.

Finnish Gypsies, like gypsies elsewhere, chose to live apart from the dominant societal groups. A Gypsy's loyalty was to his or her family and to Gypsies in general. Marriages with non-Gypsies were uncommon, and the Gypsies' own language, spoken as a first language only by a few in the 1980s, was used to keep outsiders away. An individual's place within Gypsy society was largely determined by age and by sex, old males having authority. A highly developed system of values and a code of conduct governed a Gypsy's behavior, and when Gypsy sanctions, violent or not, were imposed, for example via "blood feuds," they had far more meaning than any legal or social sanctions of Finnish society.

Unlike the Lapps, who lived concentrated in a single region, the Gypsies lived throughout Finland. While most Lapps wore ordinary clothing in their everyday life, Gypsies could be identified by their dress; the men generally wore high boots and the women almost always dressed in very full, long velvet skirts. Like most Lapps, however, Gypsies also had largely abandoned a nomadic way of life and had permanent residences. Gypsy men had for centuries worked as horse traders, but they had adapted themselves to postwar Finland by being active as horse breeders and as dealers in cars and scrap metal. Women continued their traditional trades of fortune telling and handicrafts.

Since the 1960s, Finnish authorities have undertaken measures to improve the Gypsies' standard of life. Generous state financial arrangements have improved their housing. Their low educational level (an estimated 20 percent of adult Gypsies could not read) was raised, in part, through more vocational training. A permanent Advisory Commission on Gypsy Affairs was set up in 1968, and in 1970 racial discrimination was outlawed through an addition to the penal code. The law punished blatant acts such as barring Gypsies from restaurants or shops or subjecting them to unusual surveillance by shopkeepers or the police.

in Finland, 800 of whom live in Helsinki and most of the remainder live in Turku. During the period of Swedish rule, Jews had been forbidden to live in Finland. Once the country became part of the Russian Empire, however, Jewish veterans of the tsarist army had the right to settle anywhere they wished within the empire. Although constrained by law to follow certain occupations, mainly those connected with the sale of clothes, the Jewish community in Finland was able to prosper, and 1890 it numbered about 1,000. Finnish independence brought complete civil rights, and during the interwar period there were some 2,000 Jews in Finland, most of them living in urban areas in the south. During World War II, Finnish authorities refused to deliver Jews to the Nazis, and the country's Jewish community survived the war virtually intact. By the 1980s, assimilation and emigration had significantly reduced the size of the community, and it was only with some difficulty that it maintained synagogues, schools, libraries, and other pertinent institutions.

had come from two major waves. About 5,000 originate from a population that immigrated in the 19th and early 20th centuries, when Finland was a grand duchy

of Imperial Russia. Another consisted of those who immigrated after the dissolution of the Soviet Union

. A significant catalyst was the right of return, based on President Koivisto

's initiative that people of Ingrian

ancestry would be allowed to immigrate to Finland.

community in Finland is historically smaller than the Jewish community; it numbered only about 900, most of whom were found in Helsinki. Lately immigration has increased the number of Muslims. The Muslims first came to Finland from Turkey in the mid-nineteenth century and have remained there ever since, active in commerce. Like their Jewish counterparts, Finnish Muslims have had difficulty maintaining all the institutions needed by a social group because of their small number. There is now (2011) about 50.000 muslims in Finland.

Demographics

Demographics are the most recent statistical characteristics of a population. These types of data are used widely in sociology , public policy, and marketing. Commonly examined demographics include gender, race, age, disabilities, mobility, home ownership, employment status, and even location...

features of the population

Population

A population is all the organisms that both belong to the same group or species and live in the same geographical area. The area that is used to define a sexual population is such that inter-breeding is possible between any pair within the area and more probable than cross-breeding with individuals...

of Finland

Finland

Finland , officially the Republic of Finland, is a Nordic country situated in the Fennoscandian region of Northern Europe. It is bordered by Sweden in the west, Norway in the north and Russia in the east, while Estonia lies to its south across the Gulf of Finland.Around 5.4 million people reside...

, including population density

Population density

Population density is a measurement of population per unit area or unit volume. It is frequently applied to living organisms, and particularly to humans...

, ethnicity

Ethnic group

An ethnic group is a group of people whose members identify with each other, through a common heritage, often consisting of a common language, a common culture and/or an ideology that stresses common ancestry or endogamy...

, education level, health of the populace, economic status, religious affiliations and other aspects of the population.

Finland

Finland

Finland , officially the Republic of Finland, is a Nordic country situated in the Fennoscandian region of Northern Europe. It is bordered by Sweden in the west, Norway in the north and Russia in the east, while Estonia lies to its south across the Gulf of Finland.Around 5.4 million people reside...

numbers some 5.4 million and has an average population density of 17 inhabitants per square kilometre. This makes it the third most sparsely populated country in Europe

Europe

Europe is, by convention, one of the world's seven continents. Comprising the westernmost peninsula of Eurasia, Europe is generally 'divided' from Asia to its east by the watershed divides of the Ural and Caucasus Mountains, the Ural River, the Caspian and Black Seas, and the waterways connecting...

, after Iceland

Iceland

Iceland , described as the Republic of Iceland, is a Nordic and European island country in the North Atlantic Ocean, on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Iceland also refers to the main island of the country, which contains almost all the population and almost all the land area. The country has a population...

and Norway

Norway

Norway , officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic unitary constitutional monarchy whose territory comprises the western portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula, Jan Mayen, and the Arctic archipelago of Svalbard and Bouvet Island. Norway has a total area of and a population of about 4.9 million...

. Population distribution is very uneven: the population is concentrated on the small southwestern coastal plain. About 64% live in towns and cities, with one million living in the Helsinki Metropolitan Area alone. In Arctic Lapland, on the other hand, there are only 2 people to every square kilometre.

The country is ethnically homogeneous, the dominant ethnicity being Finnish people. The official languages are Finnish

Finnish language

Finnish is the language spoken by the majority of the population in Finland Primarily for use by restaurant menus and by ethnic Finns outside Finland. It is one of the two official languages of Finland and an official minority language in Sweden. In Sweden, both standard Finnish and Meänkieli, a...

and Swedish

Swedish language

Swedish is a North Germanic language, spoken by approximately 10 million people, predominantly in Sweden and parts of Finland, especially along its coast and on the Åland islands. It is largely mutually intelligible with Norwegian and Danish...

, the latter being the native language of about five per cent of the Finnish population. From the 13th to the early 19th century Finland was a part of the Kingdom of Sweden. The Swedish-speakers are known as Swedish-speaking Finns (finlandssvenskar in Swedish, suomenruotsalaiset in Finnish).

With 79 percent of Finns in its congregation, the Lutheran Church is the largest in the country.

The earliest inhabitants of most of the land area that makes up today's Finland and Scandinavia were in all likehood hunter-gatherers whose closest successors in modern terms would probably be the Sami people

Sami people

The Sami people, also spelled Sámi, or Saami, are the arctic indigenous people inhabiting Sápmi, which today encompasses parts of far northern Sweden, Norway, Finland, the Kola Peninsula of Russia, and the border area between south and middle Sweden and Norway. The Sámi are Europe’s northernmost...

(formerly known as the Lapps). There are 4,500 of them living in Finland today and they are recognised as a minority and speak three distinct languages: Northern Sami

Northern Sami

Northern or North Sami is the most widely spoken of all Sami languages. The speaking area of Northern Sami covers the northern parts of Norway, Sweden and Finland...

, Inari Sami

Inari Sami

Inari Sámi is a Uralic, Sami language spoken by the Inari Sami of Finland. It has approximately 300 speakers, the majority of whom are middle-aged or older and live in the municipality of Inari. According to the Sami Parliament of Finland 269 persons used Inari Sami as their first language. It is...

and Skolt Sami

Skolt Sami

Skolt Sami is a Uralic, Sami language spoken by approximately 400 speakers in Finland, mainly in Sevettijärvi, and approximately 20–30 speakers of the Njuõˊttjäuˊrr dialect in an area surrounding Lake Lovozero in Russia. Skolt Sami used to also be spoken on the Neiden area of Norway,...

. They have been living north of the Arctic Circle

Arctic Circle

The Arctic Circle is one of the five major circles of latitude that mark maps of the Earth. For Epoch 2011, it is the parallel of latitude that runs north of the Equator....

for more than 7,000 years now, but today are a 5% minority in their native Lapland Province. During the late 19th and 20th century there was significant emigration

Emigration

Emigration is the act of leaving one's country or region to settle in another. It is the same as immigration but from the perspective of the country of origin. Human movement before the establishment of political boundaries or within one state is termed migration. There are many reasons why people...

, particularly from rural areas to Sweden

Sweden

Sweden , officially the Kingdom of Sweden , is a Nordic country on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. Sweden borders with Norway and Finland and is connected to Denmark by a bridge-tunnel across the Öresund....

and North America

North America

North America is a continent wholly within the Northern Hemisphere and almost wholly within the Western Hemisphere. It is also considered a northern subcontinent of the Americas...

, while most immigrants into Finland itself come from other European countries.

Population

- At the end of 2008: 5,304,840

- At the end of 2009: 5,351,427

- At the end of 2010: 5,375,276

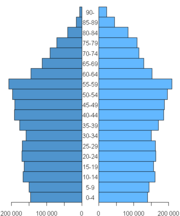

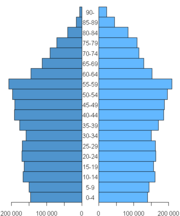

Age structure

At the end of 2009.- 0-14 years: 16.6% (male 459,950; female 441,220)

- 15-64 years: 66.4% (male 1,772,600; female 1,734,450)

- 65 years and over: 17.0% (male 351,180; female 517,530)

Families

The profound demographic and economic changes that occurred in Finland after World War II affected the Finnish family. Families became smaller, dropping from an average of 3.6 persons in 1950 to an average of 2.7 by 1975. Family composition did not change much in that quarter of a century, however, and in 1975 the percentage of families that consisted of a man and a woman was 24.4; of a couple and children, 61.9; of a woman with offspring, 11.8; of a man and offspring, 1.9. These percentages are not markedly different from those of 1950. Change was seen in the number of children per family, which fell from an average of 2.24 in 1950 to an average of 1.7 in the mid-1980s, and large families were rare. Only 2 percent of families had four or more children, while 51 percent had one child; 38 percent, two children; and 9 percent, three children. The number of Finns under the age of 18 dropped from 1.5 million in 1960 to 1.2 million in 1980.Vital statistics

Births and deaths

| Average population (x 1000) | Live births | Deaths | Natural change | Crude birth rate (per 1000) | Crude death rate (per 1000) | Natural change (per 1000) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1900 | 2 646 | 86 339 | 57 915 | 28 424 | 32.6 | 21.9 | 10.7 |

| 1901 | 2 667 | 88 637 | 56 225 | 32 412 | 33.2 | 21.1 | 12.2 |

| 1902 | 2 686 | 87 082 | 50 999 | 36 083 | 32.4 | 19.0 | 13.4 |

| 1903 | 2 706 | 85 120 | 49 992 | 35 128 | 31.5 | 18.5 | 13.0 |

| 1904 | 2 735 | 90 253 | 50 227 | 40 026 | 33.0 | 18.4 | 14.7 |

| 1905 | 2 762 | 87 841 | 52 773 | 35 068 | 31.8 | 19.1 | 12.7 |

| 1906 | 2 788 | 91 401 | 50 857 | 40 544 | 32.8 | 18.2 | 14.5 |

| 1907 | 2 821 | 92 457 | 53 028 | 39 429 | 32.8 | 18.8 | 14.0 |

| 1908 | 2 861 | 92 146 | 55 305 | 36 841 | 32.2 | 19.3 | 12.9 |

| 1909 | 2 899 | 95 005 | 50 577 | 44 428 | 32.8 | 17.4 | 15.3 |

| 1910 | 2 929 | 92 984 | 51 007 | 41 977 | 31.7 | 17.4 | 14.3 |

| 1911 | 2 962 | 91 238 | 51 648 | 39 590 | 30.8 | 17.4 | 13.4 |

| 1912 | 2 998 | 92 275 | 51 645 | 40 630 | 30.8 | 17.2 | 13.5 |

| 1913 | 3 026 | 87 250 | 51 876 | 35 374 | 28.8 | 17.1 | 11.7 |

| 1914 | 3 053 | 87 577 | 50 690 | 36 887 | 28.7 | 16.6 | 12.1 |

| 1915 | 3 083 | 83 306 | 52 205 | 31 101 | 27.0 | 16.9 | 10.1 |

| 1916 | 3 105 | 79 653 | 54 577 | 25 076 | 25.7 | 17.6 | 8.1 |

| 1917 | 3 124 | 81 046 | 58 863 | 22 183 | 25.9 | 18.8 | 7.1 |

| 1918 | 3 125 | 79 494 | 95 102 | -15 608 | 25.4 | 30.4 | -5.0 |

| 1919 | 3 117 | 63 896 | 62 932 | 964 | 20.5 | 20.2 | 0.3 |

| 1920 | 3 133 | 84 714 | 53 304 | 31 410 | 27.0 | 17.0 | 10.0 |

| 1921 | 3 170 | 82 165 | 47 361 | 34 804 | 25.9 | 14.9 | 11.0 |

| 1922 | 3 211 | 80 140 | 49 180 | 30 960 | 25.0 | 15.3 | 9.6 |

| 1923 | 3 243 | 81 961 | 47 556 | 34 405 | 25.3 | 14.7 | 10.6 |

| 1924 | 3 272 | 78 057 | 53 442 | 24 615 | 23.9 | 16.3 | 7.5 |

| 1925 | 3 304 | 78 260 | 47 493 | 30 767 | 23.7 | 14.4 | 9.3 |

| 1926 | 3 339 | 76 875 | 47 526 | 29 349 | 23.0 | 14.2 | 8.8 |

| 1927 | 3 368 | 75 611 | 51 727 | 23 884 | 22.5 | 15.4 | 7.1 |

| 1928 | 3 396 | 77 523 | 48 713 | 28 810 | 22.8 | 14.3 | 8.5 |

| 1929 | 3 424 | 76 011 | 54 489 | 21 522 | 22.2 | 15.9 | 6.3 |

| 1930 | 3 449 | 75 236 | 48 240 | 26 996 | 21.8 | 14.0 | 7.8 |

| 1931 | 3 476 | 71 866 | 48 968 | 22 898 | 20.7 | 14.1 | 6.6 |

| 1932 | 3 503 | 69 352 | 46 700 | 22 652 | 19.8 | 13.3 | 6.5 |

| 1933 | 3 526 | 65 047 | 47 960 | 17 087 | 18.4 | 13.6 | 4.8 |

| 1934 | 3 549 | 67 713 | 46 318 | 21 395 | 19.1 | 13.1 | 6.0 |

| 1935 | 3 576 | 69 942 | 45 370 | 24 572 | 19.6 | 12.7 | 6.9 |

| 1936 | 3 601 | 68 895 | 49 124 | 19 771 | 19.1 | 13.6 | 5.5 |

| 1937 | 3 626 | 72 319 | 46 466 | 25 853 | 19.9 | 12.8 | 7.1 |

| 1938 | 3 656 | 76 695 | 46 930 | 29 765 | 21.0 | 12.8 | 8.1 |

| 1939 | 3 686 | 78 164 | 52 614 | 25 550 | 21.2 | 14.3 | 6.9 |

| 1940 | 3 698 | 65 849 | 71 846 | -5 997 | 17.8 | 19.4 | -1.6 |

| 1941 | 3 702 | 89 565 | 73 334 | 16 231 | 24.2 | 19.8 | 4.4 |

| 1942 | 3 708 | 61 672 | 56 141 | 5 531 | 16.6 | 15.1 | 1.5 |

| 1943 | 3 721 | 76 112 | 49 634 | 26 478 | 20.5 | 13.3 | 7.1 |

| 1944 | 3 735 | 79 446 | 70 570 | 8 876 | 21.3 | 18.9 | 2.4 |

| 1945 | 3 758 | 95 758 | 49 046 | 46 712 | 25.5 | 13.1 | 12.4 |

| 1946 | 3 806 | 106 075 | 44 748 | 61 327 | 27.9 | 11.8 | 16.1 |

| 1947 | 3 859 | 108 168 | 46 053 | 62 115 | 28.0 | 11.9 | 16.1 |

| 1948 | 3 912 | 107 759 | 43 668 | 64 091 | 27.5 | 11.2 | 16.4 |

| 1949 | 3 963 | 103 515 | 44 501 | 59 014 | 26.1 | 11.2 | 14.9 |

| 1950 | 4 009 | 98 065 | 40 681 | 57 384 | 24.5 | 10.1 | 14.3 |

| 1951 | 4 047 | 93 063 | 40 386 | 52 677 | 23.0 | 10.0 | 13.0 |

| 1952 | 4 090 | 94 314 | 39 024 | 55 290 | 23.1 | 9.5 | 13.5 |

| 1953 | 4 139 | 90 866 | 39 925 | 50 941 | 22.0 | 9.6 | 12.3 |

| 1954 | 4 187 | 89 845 | 37 988 | 51 857 | 21.5 | 9.1 | 12.4 |

| 1955 | 4 235 | 89 740 | 39 573 | 50 167 | 21.2 | 9.3 | 11.8 |

| 1956 | 4 282 | 88 896 | 38 713 | 50 183 | 20.8 | 9.0 | 11.7 |

| 1957 | 4 324 | 86 985 | 40 741 | 46 244 | 20.1 | 9.4 | 10.7 |

| 1958 | 4 360 | 81 148 | 38 833 | 42 315 | 18.6 | 8.9 | 9.7 |

| 1959 | 4 395 | 83 253 | 38 827 | 44 426 | 18.9 | 8.8 | 10.1 |

| 1960 | 4 430 | 82 129 | 39 797 | 42 332 | 18.5 | 9.0 | 9.6 |

| 1961 | 4 461 | 81 996 | 40 616 | 41 380 | 18.4 | 9.1 | 9.3 |

| 1962 | 4 491 | 81 454 | 42 889 | 38 565 | 18.1 | 9.5 | 8.6 |

| 1963 | 4 523 | 82 251 | 42 010 | 40 241 | 18.2 | 9.3 | 8.9 |

| 1964 | 4 549 | 80 428 | 42 512 | 37 916 | 17.7 | 9.3 | 8.3 |

| 1965 | 4 564 | 77 885 | 44 473 | 33 412 | 17.1 | 9.7 | 7.3 |

| 1966 | 4 581 | 77 697 | 43 548 | 34 149 | 17.0 | 9.5 | 7.5 |

| 1967 | 4 606 | 77 289 | 43 790 | 33 499 | 16.8 | 9.5 | 7.3 |

| 1968 | 4 626 | 73 654 | 45 013 | 28 641 | 15.9 | 9.7 | 6.2 |

| 1969 | 4 624 | 67 450 | 45 966 | 21 484 | 14.6 | 9.9 | 4.6 |

| 1970 | 4 606 | 64 559 | 44 119 | 20 440 | 14.0 | 9.6 | 4.4 |

| 1971 | 4 612 | 61 067 | 45 876 | 15 191 | 13.2 | 9.9 | 3.3 |

| 1972 | 4 640 | 58 864 | 43 958 | 14 906 | 12.7 | 9.5 | 3.2 |

| 1973 | 4 666 | 56 787 | 43 410 | 13 377 | 12.2 | 9.3 | 2.9 |

| 1974 | 4 691 | 62 472 | 44 676 | 17 796 | 13.3 | 9.5 | 3.8 |

| 1975 | 4 711 | 65 719 | 43 828 | 21 891 | 14.0 | 9.3 | 4.6 |

| 1976 | 4 726 | 66 846 | 44 786 | 22 060 | 14.1 | 9.5 | 4.7 |

| 1977 | 4 739 | 65 659 | 44 065 | 21 594 | 13.9 | 9.3 | 4.6 |

| 1978 | 4 753 | 63 983 | 43 692 | 20 291 | 13.5 | 9.2 | 4.3 |

| 1979 | 4 765 | 63 428 | 43 738 | 19 690 | 13.3 | 9.2 | 4.1 |

| 1980 | 4 780 | 63 064 | 44 398 | 18 666 | 13.2 | 9.3 | 3.9 |

| 1981 | 4 800 | 63 469 | 44 404 | 19 065 | 13.2 | 9.3 | 4.0 |

| 1982 | 4 827 | 66 106 | 43 408 | 22 698 | 13.7 | 9.0 | 4.7 |

| 1983 | 4 856 | 66 892 | 45 388 | 21 504 | 13.8 | 9.3 | 4.4 |

| 1984 | 4 882 | 65 076 | 45 098 | 19 978 | 13.3 | 9.2 | 4.1 |

| 1985 | 4 902 | 62 796 | 48 198 | 14 598 | 12.8 | 9.8 | 3.0 |

| 1986 | 4 918 | 60 632 | 47 135 | 13 497 | 12.3 | 9.6 | 2.7 |

| 1987 | 4 932 | 59 827 | 47 949 | 11 878 | 12.1 | 9.7 | 2.4 |

| 1988 | 4 946 | 63 316 | 49 063 | 14 253 | 12.8 | 9.9 | 2.9 |

| 1989 | 4 964 | 63 348 | 49 110 | 14 238 | 12.8 | 9.9 | 2.9 |

| 1990 | 4 986 | 65 549 | 50 028 | 15 521 | 13.1 | 10.0 | 3.1 |

| 1991 | 5 014 | 65 680 | 49 271 | 16 409 | 13.1 | 9.8 | 3.3 |

| 1992 | 5 042 | 66 877 | 49 523 | 17 354 | 13.3 | 9.8 | 3.4 |

| 1993 | 5 066 | 64 826 | 50 988 | 13 838 | 12.8 | 10.1 | 2.7 |

| 1994 | 5 088 | 65 231 | 48 000 | 17 231 | 12.8 | 9.4 | 3.4 |

| 1995 | 5 108 | 63 067 | 49 280 | 13 787 | 12.3 | 9.6 | 2.7 |

| 1996 | 5 125 | 60 723 | 49 167 | 11 556 | 11.8 | 9.6 | 2.3 |

| 1997 | 5 140 | 59 329 | 49 108 | 10 221 | 11.5 | 9.6 | 2.0 |

| 1998 | 5 153 | 57 108 | 49 283 | 7 825 | 11.1 | 9.6 | 1.5 |

| 1999 | 5 165 | 57 574 | 49 345 | 8 229 | 11.1 | 9.6 | 1.6 |

| 2000 | 5 176 | 56 742 | 49 339 | 7 403 | 11.0 | 9.5 | 1.4 |

| 2001 | 5 188 | 56 189 | 48 550 | 7 639 | 10.8 | 9.4 | 1.5 |

| 2002 | 5 201 | 55 555 | 49 418 | 6 137 | 10.7 | 9.5 | 1.2 |

| 2003 | 5 213 | 56 630 | 48 996 | 7 634 | 10.9 | 9.4 | 1.5 |

| 2004 | 5 228 | 57 758 | 47 600 | 10 158 | 11.0 | 9.1 | 1.9 |

| 2005 | 5 246 | 57 745 | 47 928 | 9 817 | 11.0 | 9.1 | 1.9 |

| 2006 | 5 266 | 58 840 | 48 065 | 10 775 | 11.2 | 9.1 | 2.0 |

| 2007 | 5 289 | 58 729 | 49 077 | 9 652 | 11.1 | 9.3 | 1.8 |

| 2008 | 5 313 | 59 350 | 49 094 | 10 256 | 11.2 | 9.2 | 1.9 |

| 2009 | 5 339 | 60 430 | 49 883 | 10 547 | 11.3 | 9.3 | 2.0 |

| 2010 | 5 374 | 60 980 | 50 887 | 10 103 | 11.4 | 9.5 | 1.9 |

Life expectancy at birth

| Year | Males | Females | Both sexes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1986 | 70.5 | 78.7 | 74.7 |

| 1996 | 73.0 | 80.5 | 76.8 |

| 2006 | 75.8 | 82.8 | 79.4 |

| 2008 | 76.3 | 83.0 | 79.7 |

| 2009 | 76.5 | 83.1 | 79.8 |

Marriage

Attitudes toward marriage have changed substantially since World War II. Most obvious was the declining marriage rate, which dropped from 8.5 marriages per 1,000 Finns in 1950 to 5.8, in 1984, a decline great enough to mean a drop also in absolute numbers. In 1950 there were 34,000 marriages, while in 1984 only 28,500 were registered, despite a growth in population of 800,000. An explanation for the decline was that there was an unprecedented number of unmarried couples. Since the late 1960s, the practice of cohabitation had become increasingly common, so much so that by the late 1970s most marriages in urban areas grew out of what Finns called "open unions." In the 1980s, it was estimated that about 8 percent of couples who lived together, approximately 200,000 people, did so without benefit of marriage. Partners of such unions usually married because of the arrival of offspring or the acquisition of property. A result of the frequency of cohabitation was that marriages were postponed, and the average age for marriage, which had been falling, began to rise in the 1970s. By 1982 the average marriage age was 24.8 years for women and 26.8 years for men, several years higher for both sexes than had been true a decade earlier.The overwhelming majority of Finns did marry, however. About 90 percent of the women had been married by the age of forty, and spinsterhood was rare. A shortage of women in rural regions, however, meant that some farmers were forced into bachelorhood.

While the number of marriages was declining, divorce became more common, increasing 250 percent between 1950 and 1980. In 1952 there were 3,500 divorces. The 1960s saw a steady increase in this rate, which averaged about 5,000 divorces a year. A high of 10,191 was reached in 1979; afterwards the divorce rate stabilized at about 9,500 per year during the first half of the 1980s.

A number of factors caused the increased frequency of divorce. One was that an increasingly secularized society viewed marriage, more often than before, as an arrangement that could be ended if it did not satisfy its partners. Another reason was that a gradually expanding welfare system could manage an ever greater portion of the family's traditional tasks, and it made couples less dependent on the institution of marriage. Government provisions for parental leave, child allowances, child care programs, and much improved health and pension plans meant that the family was no longer essential for the care of children and aged relatives. A further cause for weakened family and marital ties was seen in the unsettling effects of the Great Migration and in the economic transformation Finland experienced during the 1960s and the 1970s. The rupture of established social patterns brought uncertainty and an increased potential for conflict into personal relationships.

External Migration

A great number of Finns emigrated to Sweden after World War II, drawn by that country's prosperity and proximity. Emigration began slowly, but, during the 1960s and the second half of the 1970s, tens of thousands left each year for their western neighbor. The peak emigration year was 1970, when 41,000 Finns settled in Sweden, which caused Finland's population actually to fall that year. Because many of the migrants later returned to Finland, definite figures cannot be calculated, but all told, an estimated 250,000 to 300,000 Finns became permanent residents of Sweden in the postwar period. The overall youthfulness of these emigrants meant that the quality of the work force available to Finnish employers was diminished and that the national birth rate slowed. At one point, every eighth Finnish child was born in Sweden. Finland's Swedish-speaking minority was hard hit by this westward migration; its numbers dropped from 350,000 to about 300,000 between 1950 and 1980. By the 1980s, a strong Finnish economy had brought an end to large-scale migration to Sweden. In fact, the overall population flow was reversed because each year several thousand more Finns returned from Sweden than left for it.

Internal Migration

However significant the long-term effects of external migration on Finnish society may have been, migration within the country had a greater impact--especially the migration which took place between the end of World War II and the mid-1970s, when half the population moved from one part of the country to another. Before World War II, internal migration had first been a centuries-long process of forming settlements ever farther to the north. Later, however, beginning in the second half of the nineteenth century with the coming of Finland's tardy industrialization, there was a slow movement from rural regions toward areas in the south where employment could be found.Postwar internal migration began with the resettlement within Finland of virtually all the inhabitants of the parts of Karelia ceded to the Soviet Union. Somewhat more than 400,000 persons, more than 10 percent of the nation's population, found new homes elsewhere in Finland, often in the less settled regions of the east and the north. In these regions, new land, which they cleared for farming, was provided for the refugees; in more populated areas, property was requisitioned. The sudden influx of these settlers was successfully dealt with in just a few years. One of the effects of rural resettlement was an increase in the number of farms during the postwar years, a unique occurrence for industrialized nations of this period.

It was, however, the postwar economic transformation that caused an even larger movement of people within Finland, a movement known to Finns as the Great Migration. It was a massive population shift from rural areas, especially those of eastern and northeastern Finland, to the urban, industrialized south). People left rural regions because the mechanization of agriculture and the forestry industry had eliminated jobs. The displaced work force went to areas where employment in the expanding industrial and service sectors was available. This movement began in the 1950s, but it was most intense during the 1960s and the first half of the 1970s, assuming proportions that in relative terms were unprecedented for a country outside the Third World. The Great Migration left behind rural areas of abandoned farms with reduced and aging populations, and it allowed the creation of a densely populated postindustrial society in the country's south.

The extent of the demographic shift to the south can be shown by the following figures. Between 1951 and 1975, the population registered an increase of 655,000. During this period, the small province of Uusimaa increased its population by 412,000, growing from 670,000 to 1,092,00; three-quarters of this growth was caused by settlers from other provinces. The population increase experienced by four other southern provinces, the Aland Islands, Turku ja Pori, Hame, and Kymi, taken together with that of Uusimaa amounted to 97 percent of the country's total population increase for these years. The population increase of the central and the northern provinces accounted for the remaining 3 percent. Provinces that experienced an actual population loss during these years were in the east and the northeast-Pohjois-Karjala, Mikkeli, and Kuopio.

One way of visualizing the shift to the south would be to draw a line, bowing slightly to the north, between the port cities of Kotka on the Gulf of Finland and Kaskinen on the Gulf of Bothnia. In 1975 the territory to the south of this line would have contained half of Finland's population. Ten years earlier, such a line, drawn farther to the north to mark off perhaps 20 percent more area, would have encompassed half the population. One hundred years earlier, half the population would have been distributed throughout more than twice as much territory. Another indication of the extent to which Finns were located in the south was that by 1980, approximately 90 percent of them lived in the southernmost 41 percent of Finland.

Ethnic minorities & languages

No official statistics are kept on ethnicities. However, statistics of the Finnish population according to language and citizinship are available.The Finnish and Swedish languages are defined as languages of the state. Additionally, Swedish is an official municipal language in municipalities with significant Swedish-speaking populations. The three Sami languages (North Sami, Inari Sami

Inari Sami

Inari Sámi is a Uralic, Sami language spoken by the Inari Sami of Finland. It has approximately 300 speakers, the majority of whom are middle-aged or older and live in the municipality of Inari. According to the Sami Parliament of Finland 269 persons used Inari Sami as their first language. It is...

, Skolt Sami

Skolt Sami

Skolt Sami is a Uralic, Sami language spoken by approximately 400 speakers in Finland, mainly in Sevettijärvi, and approximately 20–30 speakers of the Njuõˊttjäuˊrr dialect in an area surrounding Lake Lovozero in Russia. Skolt Sami used to also be spoken on the Neiden area of Norway,...

) are official in certain municipalities of Lapland.

Finnish people — Finns — speak the Finnish language

Finnish language

Finnish is the language spoken by the majority of the population in Finland Primarily for use by restaurant menus and by ethnic Finns outside Finland. It is one of the two official languages of Finland and an official minority language in Sweden. In Sweden, both standard Finnish and Meänkieli, a...

, which the dominant language and is spoken almost everywhere in the country. Native Finnish speakers are otherwise recognized as an ethnicity.

Population of mainland Finland (excluding Aland) according to language, 1990-2010 http://pxweb2.stat.fi/Dialog/varval.asp?ma=030_vaerak_tau_102_en&ti=Language+according+to+age+and+gender+by+region+1990+%2D+2010&path=../Database/StatFin/vrm/vaerak/&lang=1&multilang=en

| Language | 1990 | 2000 | 2010 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Finnish | 4,674,095 | 4,787,259 | 4,856,529 |

| Swedish | 273,495 | 267,488 | 265,982 |

| Sami Sami languages Sami or Saami is a general name for a group of Uralic languages spoken by the Sami people in parts of northern Finland, Norway, Sweden and extreme northwestern Russia, in Northern Europe. Sami is frequently and erroneously believed to be a single language. Several names are used for the Sami... |

1,734 | 1,734 | 1,832 |

| Foreign languages: | 24,550 | 98,858 | 222,926 |

| Russian | 3,884 | 28,179 | 54,546 |

| Estonian | 1,394 | 10,153 | 28,355 |

| Somali | 0 | 6,454 | 12,985 |

| English | 3,518 | 6,850 | 12,758 |

| Arabic | 1,133 | 4,875 | 10,379 |

The classification of the Swedish-speakers as an ethnicity is controversial. The government only considers the "working language", Finnish or Swedish, of the person, and "bilinguality" has no official standing. Significant populations of Swedish-speakers are found in coastal areas, from Ostrobothnia to the southern coast, and in the archipelago of Åland. Coastal cities, however, are majority Finnish-speaking, with a few small towns as exceptions. There are very few Swedish-speakers in the inland.

Sami

The oldest known inhabitants of Finland are the Sami, who were already settled there when the Finns arrived in the southern part of the country about 2,000 years ago. The Sami were distantly related to the Finns, and both spoke a non-Indo- European language belonging to the Finno-Ugric family of languages. Once present throughout the country, the Sami gradually moved northward under the pressure of the advancing Finns. As they were a nomadic people in a sparsely settled land, the Sami were always able to find new and open territory in which to follow their traditional activities of hunting, fishing, and slash-and-burn agriculture. By the sixteenth century, most Sami lived in the northern half of the country, and it was during this period that they converted to Christianity. By the nineteenth century, most of them lived in the parts of Lapland that were still their home in the 1980s. The last major shift in Sami settlement was the migration westward of 600 Skolt Sami from the Petsamo region after it was ceded to the Soviet Union in 1944. A reminder of their eastern origin was their Orthodox faith; the remaining 85 percent of Finland's Sami were Lutheran.About 90 percent of Finland's 4,400 Sami lived in the municipalities of Enontekiö, Inari, and Utsjoki, and in the reindeer herding-area of Sodankyla. According to Finnish regulations, anyone who spoke the Lapp language, Sami, or who had a relative who was a Lapp, was registered as a Lapp in census records. Finnish Sami spoke three Sami dialects, but by the late 1980s perhaps only a minority actually had Sami as their first language. Lapp children had the right to instruction in Sami, but there were few qualified instructors or textbooks available. One reason for the scarcity of written material in Sami is that the three dialects spoken in Finland made agreement about a common orthography difficult. Perhaps these shortcomings explained why a 1979 study found the educational level of Sami to be considerably lower than that of other Finns.

Few Finnish Sami actually led the traditional nomadic life pictured in school geography texts and in travel brochures. Although many Sami living in rural regions of Lapland earned some of their livelihood from reindeer herding, it was estimated that Sami owned no more than one-third of Finland's 200,000 reindeer. Only 5 percent of Finnish Sami had the herds of 250 to 300 reindeer needed to live entirely from this kind of work. Most Sami worked at more routine activities, including farming, construction, and service industries such as tourism. Often a variety of jobs and sources of income supported Lapp families, which were, on the average, twice the size of a typical Finnish family. Sami also were aided by old-age pensions and by government welfare, which provided a greater share of their income than it did for Finns as a whole.

There have been many efforts over the years by Finnish authorities to safeguard the Sami' culture and way of life and to ease their entry into modern society. Officials created bodies that dealt with the Lapp minority, or formed committees that studied their situation. An early body was the Society for the Promotion of Lapp Culture, formed in 1932. In 1960 the government created the Advisory Commission on Lapp Affairs. The Sami themselves formed the Samii Litto in 1945 and the Johti Sabmelazzat, a more aggressive organization, in 1968. In 1973 the government arranged for elections every four years to a twentymember Sami Parlamenta that was to advise authorities. On the international level, there was the Nordic Sami Council of 1956, and there has been a regularly occurring regional conference since then that represented--in addition to Finland's Sami-- Norway's 20,000 Sami, Sweden's 10,000 Sami, and the 1,000 to 2,000 Sami who remained in the Kola Peninsula in Russia.

Gypsies

Gypsies, also called Kale and Roma, have been present in Finland since the second half of the sixteenth century. With their unusual dress, unique customs, and specialized trades for earning their livelihood, Gypsies have stood out, and their stay in the country has not been an easy one. They have suffered periodic harassment from the hands of both private citizens and public officials, and the last of the special laws directed against them was repealed only in 1883. Even in the second half of the 1980s, Finland's 5,000 to 6,000 Gypsies remained a distinct group, separated from the general population both by their own choice and by the fears and the prejudices many Finns felt toward them.Finnish Gypsies, like gypsies elsewhere, chose to live apart from the dominant societal groups. A Gypsy's loyalty was to his or her family and to Gypsies in general. Marriages with non-Gypsies were uncommon, and the Gypsies' own language, spoken as a first language only by a few in the 1980s, was used to keep outsiders away. An individual's place within Gypsy society was largely determined by age and by sex, old males having authority. A highly developed system of values and a code of conduct governed a Gypsy's behavior, and when Gypsy sanctions, violent or not, were imposed, for example via "blood feuds," they had far more meaning than any legal or social sanctions of Finnish society.

Unlike the Lapps, who lived concentrated in a single region, the Gypsies lived throughout Finland. While most Lapps wore ordinary clothing in their everyday life, Gypsies could be identified by their dress; the men generally wore high boots and the women almost always dressed in very full, long velvet skirts. Like most Lapps, however, Gypsies also had largely abandoned a nomadic way of life and had permanent residences. Gypsy men had for centuries worked as horse traders, but they had adapted themselves to postwar Finland by being active as horse breeders and as dealers in cars and scrap metal. Women continued their traditional trades of fortune telling and handicrafts.

Since the 1960s, Finnish authorities have undertaken measures to improve the Gypsies' standard of life. Generous state financial arrangements have improved their housing. Their low educational level (an estimated 20 percent of adult Gypsies could not read) was raised, in part, through more vocational training. A permanent Advisory Commission on Gypsy Affairs was set up in 1968, and in 1970 racial discrimination was outlawed through an addition to the penal code. The law punished blatant acts such as barring Gypsies from restaurants or shops or subjecting them to unusual surveillance by shopkeepers or the police.

Jews

There are about 1,300 JewsJews

The Jews , also known as the Jewish people, are a nation and ethnoreligious group originating in the Israelites or Hebrews of the Ancient Near East. The Jewish ethnicity, nationality, and religion are strongly interrelated, as Judaism is the traditional faith of the Jewish nation...

in Finland, 800 of whom live in Helsinki and most of the remainder live in Turku. During the period of Swedish rule, Jews had been forbidden to live in Finland. Once the country became part of the Russian Empire, however, Jewish veterans of the tsarist army had the right to settle anywhere they wished within the empire. Although constrained by law to follow certain occupations, mainly those connected with the sale of clothes, the Jewish community in Finland was able to prosper, and 1890 it numbered about 1,000. Finnish independence brought complete civil rights, and during the interwar period there were some 2,000 Jews in Finland, most of them living in urban areas in the south. During World War II, Finnish authorities refused to deliver Jews to the Nazis, and the country's Jewish community survived the war virtually intact. By the 1980s, assimilation and emigration had significantly reduced the size of the community, and it was only with some difficulty that it maintained synagogues, schools, libraries, and other pertinent institutions.

Russians

Russians in FinlandRussians in Finland

Russians in Finland constitute a linguistic and ethnic minority in Finland. About 27,000 people have a citizenship of Russian Federation and Russian is the mother language of about 48,000 people in Finland, which represents about 0.8% of the population.Russians citizens who moved before the Second...

had come from two major waves. About 5,000 originate from a population that immigrated in the 19th and early 20th centuries, when Finland was a grand duchy

Grand duchy

A grand duchy, sometimes referred to as a grand dukedom, is a territory whose head of state is a monarch, either a grand duke or grand duchess.Today Luxembourg is the only remaining grand duchy...

of Imperial Russia. Another consisted of those who immigrated after the dissolution of the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

. A significant catalyst was the right of return, based on President Koivisto

Mauno Koivisto

Mauno Henrik Koivisto is a Finnish politician who served as the ninth President of Finland from 1982 to 1994. He also served as Prime Minister 1968–1970 and 1979–1982...

's initiative that people of Ingrian

Ingrian Finns

The Ingrian Finns are the Finnish population of Ingria descending from Lutheran Finnish immigrants introduced to the area in the 17th century, when Finland and Ingria were both part of the Swedish Empire...

ancestry would be allowed to immigrate to Finland.

Muslims

The MuslimMuslim

A Muslim, also spelled Moslem, is an adherent of Islam, a monotheistic, Abrahamic religion based on the Quran, which Muslims consider the verbatim word of God as revealed to prophet Muhammad. "Muslim" is the Arabic term for "submitter" .Muslims believe that God is one and incomparable...

community in Finland is historically smaller than the Jewish community; it numbered only about 900, most of whom were found in Helsinki. Lately immigration has increased the number of Muslims. The Muslims first came to Finland from Turkey in the mid-nineteenth century and have remained there ever since, active in commerce. Like their Jewish counterparts, Finnish Muslims have had difficulty maintaining all the institutions needed by a social group because of their small number. There is now (2011) about 50.000 muslims in Finland.

Religion

At the end of 2009.- Evangelical Lutheran 79.9 % (Evangelical Lutheran Church of FinlandEvangelical Lutheran Church of FinlandThe Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland is the national church of Finland. The church professes the Lutheran branch of Christianity, and is a member of the Porvoo Communion....

, state churchState churchState churches are organizational bodies within a Christian denomination which are given official status or operated by a state.State churches are not necessarily national churches in the ethnic sense of the term, but the two concepts may overlap in the case of a nation state where the state...

) - Christian OrthodoxEastern Orthodox ChurchThe Orthodox Church, officially called the Orthodox Catholic Church and commonly referred to as the Eastern Orthodox Church, is the second largest Christian denomination in the world, with an estimated 300 million adherents mainly in the countries of Belarus, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Georgia, Greece,...

1.1 % (Finnish Orthodox ChurchFinnish Orthodox ChurchThe Finnish Orthodox Church is an autonomous Orthodox archdiocese of the Patriarchate of Constantinople. The Church has a legal position as a national church in the country, along with the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland....

, second state church) - other ca. 1.3 %

- none ca. 17.7%