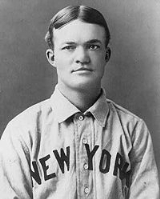

Dummy Taylor

Encyclopedia

Luther Haden "Dummy" Taylor (February 21, 1875 – August 22, 1958) was a deaf-mute

American right-handed pitcher

in Major League Baseball

from 1900 to 1908. He played for the New York Giants

and Cleveland Bronchos

and was one of the key pitchers on the Giants' National League

championship teams of 1904 and 1905.

In 1901, his first full season in the major leagues, Taylor led the National League

by pitching

in 45 games and ranked second in the league with 37 complete game

s. In 1904, he won 21 games for the Giants, and in 1906 his 2.20 ERA was the lowest on a pitching staff that also included Baseball Hall of Famers

Christy Mathewson

(2.97 ERA), and "Iron Man" Joe McGinnity (2.25 ERA).

Taylor was the first and only successful deaf pitcher in Major League Baseball and was regarded, along with Dummy Hoy

, as a role model and hero in the American deaf community in the early 20th century. In the 1900s, Taylor was reported to be the highest paid deaf person in the United States. He was also known as the comedian of the Giants teams, waving a lit lantern when an umpire refused to call a game due to darkness and coaching at third base in rubber boots when an umpire refused to call a game due to rain.

In 2000, author Darryl Brock wrote the historical novel Havana Heat

about Taylor's experience in professional baseball. The book won the Dave Moore Award

in 2000 as the "most important baseball book" published that year.

in 1875. He was the son of Arnold B. Taylor, a farmer, and his wife, Emaline (Chatman) Taylor. At the time of the 1880 United States Census, Taylor was living in rural Jefferson County, Kansas

with his parents, two older brothers, and two older sisters. Some accounts indicate that Taylor was born deaf. However, at age four, Taylor was not listed as being "deaf and dumb" or otherwise handicapped in the family's U.S. Census record. By age 10, Taylor was living at the Kansas School For the Deaf

in Olathe, Kansas

. He was listed in the 1885 Kansas State Census as a pupil at the Deaf and Dumb Institute.

Taylor continued to live at the Kansas School for the Deaf through his high school years. He was a pitcher for the school baseball team and also participated in boxing. Interviewed in 1942, Taylor recalled that he had dreams as a boy of becoming a great boxer, but his parents objected. At the time of the 1895 Kansas State Census, Taylor was living in Olathe.

. He then played at Lincoln, Illinois

, and with minor league teams in Wabash

, Crawfordsville

, Danville

and Terre Haute, Indiana

. In 1897, he played for a minor league team in Mattoon, Illinois

. He played for the Shreveport Tigers of the Southern League

in 1898 and 1899.

In 1900, Taylor began the season playing for Albany, New York

. At the time of the U.S. Census in June 1900, Taylor was residing at a boarding house in Albany; his occupation was listed as a printer.

. He made his major league debut on August 27, 1900. In his first game for the Giants, five Boston players tried to take advantage of Taylor's deafness by trying to steal third base. Interviewed in 1942, Taylor recalled with pride, "I nailed each one. I walked over to (Herman) Long, the last man caught, and let him know by signs I could hear him stealing." Appearing in 11 games for the 1900 Giants, Taylor compiled a 4–3 record with a 2.45 earned run average

(ERA).

In his second season in the major leagues, Taylor was a workhorse for the 1901 Giants

. He led the National League

with 43 games started and by appearing in a total of 45 games. He also ranked second in the league with 37 complete games, 353⅓ innings pitched, and 1,518 batters faced. Despite maintaining a respectable 3.18 ERA, Taylor played for a weak-hitting Giants team that finished 7th out of 8 teams in hits and runs produced. With the absence of run support, Taylor finished the season with a win-loss record of 18–27. His 27 losses in 1901 is tied for the second most given up by any pitcher in Major League Baseball during the 20th century (trailing Vic Willis

's 29 losses in 1905).

. He recalled that American League teams were "waving big money at us" in the winter before the 1902 season. Taylor appeared in four games for the Bronchos, all as a starter. Despite a 1.59 ERA, Taylor again suffered from a lack of run support and compiled a record of 1–3 in Cleveland.

to persuade Taylor to return to the Giants. Bowerman sat in the stands while Taylor was pitching and negotiated the terms of Taylor's return to the Giants by signing. Taylor recalled:

Taylor appeared in 26 games for the 1902 Giants and had 22 complete games. Taylor's 7–15 record for the 1902 Giants was again the result of playing for a remarkably weak-hitting team, as the 1902 Giants finished in last place in runs, hits and batting average. Even Christy Mathewson

, who was Taylor's teammate on the 1902 Giants, registered a losing record in 1902 with an ERA (2.12) only marginally better than Taylor.

In 1903, John McGraw

took over as the manager of the Giants. McGraw quickly turned the Giants into one of the best teams in the National League, with Taylor, Mathewson, and Iron Man Joe McGinnity as his pitching stars. Taylor had his most successful season in 1904. With strong support from a Giants team that finished first in the National League in runs and hits, Taylor compiled a 21–15 record in 1904. He was among the National League leaders that year with 21 wins (4th), five shutouts (3rd), 1.033 WHIP

(5th), 136 strikeouts (6th), and a .991 fielding percentage (2nd).

In 1905, Taylor helped lead the Giants to their second consecutive National League pennant. Taylor appeared in 32 games and compiled a record of 16–9 with a 2.66 ERA. Taylor was scheduled to pitch in the third game of the 1905 World Series

, but the game was cancelled because of rain, and Christy Mathewson was able to pitch with an extra day of rest when the Series resumed. (Mathewson pitched three complete-game shutouts in the 1905 World Series.)

Although the Giants fell short of a third consecutive pennant in 1906, Taylor had another strong year, compiling a 17–9 record and a 2.20 ERA. His 1906 ERA was the lowest on a pitching staff that also included Hall of Fame

rs Christy Mathewson (2.97 ERA) and Iron Man Joe McGinnity (2.25 ERA). Taylor also ranked 6th in the National League with a .654 winning percentage in 1906.

In 1907, Taylor went 11–7 with a 2.42 ERA and a 1.117 WHIP. He pitched his final major league season in 1908, compiling an 8–5 record with a 2.33 ERA.

in the Eastern League. He won 32 games for Buffalo in 1909 and 1910 and played in the minor leagues from 1909 to 1915. In his final season of organized baseball, he compiled an 18–11 record for the Utica Utes in the New York State League

.

. He is credited with helping to expand and make universal the use of sign language throughout the modern baseball infield, including but not limited to the use of pitching signs. According to Sean Lahman in his biography of Taylor, "The Giants didn't just add Taylor to their roster; they embraced him as a member of the family. Player-manager George Davis

learned sign language and encouraged his players to do the same. John McGraw did likewise when he took over as Giants manager in July 1902." In Lawrence Ritter

's The Glory of Their Times

, Taylor's teammate, Fred Snodgrass

, recalled:

During his eight seasons in Major League Baseball, Taylor's success won acclaim in the deaf press, including The Silent Worker, and he became a role model and hero for the deaf community. An article in The Saturday Evening Post

noted that "wherever Taylor goes he will always be visited by scores of the silent fraternity among whom he is regarded as a prodigy."

On May 16, 1902, Taylor pitched against Dummy Hoy

in Cincinnati, Ohio. The occasion was reported to be "the first and only time two deaf professional athletes competed against one another." When Hoy came to bat for the first time, he signed to Taylor, "I'm glad to see you." Hoy collected two hits off Taylor, but Taylor got the win as the Giants beat the Reds

5–3.

Taylor's nickname, "Dummy," was commonly applied to "deaf and dumb" baseball players in the late 19th and early 20th century. Dummy Dundon

and Dummy Hoy were the first professional baseball players to receive the appellation. Others include Dummy Deegan

, Dummy Leitner

, Dummy Lynch

, Dummy Murphy

and Dummy Stephenson

. Although he accepted the nickname in his playing days, Taylor noted in a 1945 interview that he and Dummy Hoy did not care for the nickname: "In the old days Hoy and I were called Dummy. It didn't hurt us. It made us fight harder." Taylor's popularity led to an outcry in the deaf press against the use of the nickname. Alexander Pach wrote an editorial in The Silent Worker in which he protested: "The highest salaried deaf man in the United States is the much heralded Dummy Taylor—I say Dummy only to serve to show how contemptible the epithet looks."

Taylor was inducted into the American Athletic Association of the Deaf Hall of Fame in 1953. He was also inducted into the Kansas Sports Hall of Fame in 2006.

, adding:

On one occasion, Taylor disagreed with the decision by umpire Bill Klem

not to call the game as darkness fell. Taylor returned to the clubhouse and came back onto the field wearing a fireman's oilskin and holding a lit lantern above his head. Klem yelled at Taylor to get off the field, but Taylor could not hear and continued with his antics until Klem finally called the game.

Honus Wagner

later wrote about a game in which the Giants were complaining about the umpire's refusal to suspend a game due to rain. Wagner wrote, "So Dummy Taylor, one of the Giant pitchers, went out to the third base coaching lines in his hip boots and a raincoat. Then the umpire did get mad. He chased Taylor out of the park, and it was funny to see Dummy trying to explain to him that he shouldn't be ejected." Taylor later recalled that the umpire, Johnston, "not only chased me, but declared the game forfeited to the other club."

Giants' manager McGraw kept Taylor in the dugout when he wasn't pitching to distract the opposing pitcher. Taylor was able to emit a "rattling shriek" just as the opposing pitcher was about to release a pitch. Teammate Mike Donlin

compared the noise to the "crazed shrieking of a jackass." Taylor biographer Sean Lahman wrote: "Umpire Charlie Zimmer once got so irritated with the shrill sound that he ejected Taylor, perhaps the only instance of a deaf player being tossed for being too noisy."

Taylor was also ejected from a baseball game by an umpire "for cursing him out in sign language." According to some accounts, the umpire was Hank O'Day

, who knew sign language. After Taylor's tirade, O'Day reportedly stepped in front of the plate and signed the following comments back at Taylor: "Listen, smart guy ... I've spent all my spare time this past week learning your language. You can't call me a blind bat any more. Now, go take a shower ... you're out of the game."

Aside from sign language, Taylor would let it be known that he disagreed with an umpire's call by holding his nose and spinning the second finger of his other hand near his temple, demonstrating his belief that the ump was screwy. In June 1905, umpire Hank O'Day

ejected Taylor for hand gestures that he interpreted to be an accusation that "I had wheels in my head." A press account described the scene:

John McGraw recalled an occasion when he, too, was cursed out by Taylor: "In sign language, Dummy consigned me to the hottest place he could think of—and he didn't mean St. Louis." Taylor was also an accomplished juggler and would often put on "a grand juggling act" in front of the Giants' dugout to amuse the fans.

. As of January 1914, he was the physical director at the Kansas School for the Deaf. At the time of the 1915 Kansas State Census, he was living in Olathe with his wife, Della M. (Ramsey) Taylor. At the time of the 1920 United States Census, Taylor was living at the Kansas School for the Deaf where he was employed as the physical instructor.

Taylor subsequently moved to Iowa where he worked as a coach at the Iowa School for the Deaf. At the time of the 1925 Iowa State Census, Taylor was living at the Iowa School for the Deaf in Lewis Township, Pottawattamie County, Iowa

.

In 1927, several newspapers reported that Taylor had died. Taylor issued a statement from his home in Iowa, emphatically denying that he was dead. Taylor's statement resulted in headlines in papers across North America such as, "'Dummy' Taylor Denies being Dead." It turned out that Taylor had been confused with another deaf baseball pitcher, Lyman "Dummy" Taylor.

At the time of the 1930 United States Census, Taylor was still living at the Iowa School for the Deaf. His occupation was listed as a coach, and he was listed as living with his wife, Della M. Taylor, who was a teacher at the school.

Taylor later became employed at the Illinois School for the Deaf in Jacksonville, Illinois

. When he was interviewed in 1942 for a feature story in The Sporting News

, Taylor was employed as a coach and "house father" at the Illinois School for the Deaf. One of Taylor's pupils, Dick Sipek

, went on to play baseball for the Cincinnati Reds

.

Having outlived his first wife, Della, who died in 1931, and second wife Lenora Borjquest, Taylor married for the third time to Lina Belle Davis from Little Rock, Arkansas

in August 1941.

Taylor also continued to be involved with professional baseball into the 1950s, umpiring local baseball games and doing scouting work for the Giants.

In August 1958, Taylor died at Our Savior's Hospital in Jacksonville, Illinois. He was buried with his first wife, Della, at Prairie City

Cemetery in Baldwin City, Kansas

.

.

Deaf-mute

For "deafness", see hearing impairment. For "Deaf" as a cultural term, see Deaf culture. For "inability to speak", see muteness.Deaf-mute is a term which was used historically to identify a person who was both deaf and could not speak...

American right-handed pitcher

Pitcher

In baseball, the pitcher is the player who throwsthe baseball from the pitcher's mound toward the catcher to begin each play, with the goal of retiring a batter, who attempts to either make contact with the pitched ball or draw a walk. In the numbering system used to record defensive plays, the...

in Major League Baseball

Major League Baseball

Major League Baseball is the highest level of professional baseball in the United States and Canada, consisting of teams that play in the National League and the American League...

from 1900 to 1908. He played for the New York Giants

History of the New York Giants (NL)

The history of the New York Giants, before the franchise moved to San Francisco, lasted from 1883 to 1957. It featured five of the franchise's six World Series wins and 17 of its 21 National League pennants...

and Cleveland Bronchos

Cleveland Indians

The Cleveland Indians are a professional baseball team based in Cleveland, Ohio. They are in the Central Division of Major League Baseball's American League. Since , they have played in Progressive Field. The team's spring training facility is in Goodyear, Arizona...

and was one of the key pitchers on the Giants' National League

National League

The National League of Professional Baseball Clubs, known simply as the National League , is the older of two leagues constituting Major League Baseball, and the world's oldest extant professional team sports league. Founded on February 2, 1876, to replace the National Association of Professional...

championship teams of 1904 and 1905.

In 1901, his first full season in the major leagues, Taylor led the National League

National League

The National League of Professional Baseball Clubs, known simply as the National League , is the older of two leagues constituting Major League Baseball, and the world's oldest extant professional team sports league. Founded on February 2, 1876, to replace the National Association of Professional...

by pitching

Pitcher

In baseball, the pitcher is the player who throwsthe baseball from the pitcher's mound toward the catcher to begin each play, with the goal of retiring a batter, who attempts to either make contact with the pitched ball or draw a walk. In the numbering system used to record defensive plays, the...

in 45 games and ranked second in the league with 37 complete game

Complete game

In baseball, a complete game is the act of a pitcher pitching an entire game without the benefit of a relief pitcher.As demonstrated by the charts below, in the early 20th century, it was common for most good Major League Baseball pitchers to pitch a complete game almost every start. Pitchers were...

s. In 1904, he won 21 games for the Giants, and in 1906 his 2.20 ERA was the lowest on a pitching staff that also included Baseball Hall of Famers

National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum is an American history museum and hall of fame, located at 25 Main Street in Cooperstown, New York, operated by private interests serving as the central point for the study of the history of baseball in the United States and beyond, the display of...

Christy Mathewson

Christy Mathewson

Christopher "Christy" Mathewson , nicknamed "Big Six", "The Christian Gentleman", or "Matty", was an American Major League Baseball right-handed pitcher. He played his entire career in what is known as the dead-ball era...

(2.97 ERA), and "Iron Man" Joe McGinnity (2.25 ERA).

Taylor was the first and only successful deaf pitcher in Major League Baseball and was regarded, along with Dummy Hoy

Dummy Hoy

William Ellsworth Hoy , nicknamed "Dummy," was an American center fielder in Major League Baseball who played for several teams from 1888 to 1902, most notably the Cincinnati Reds and two Washington, D.C...

, as a role model and hero in the American deaf community in the early 20th century. In the 1900s, Taylor was reported to be the highest paid deaf person in the United States. He was also known as the comedian of the Giants teams, waving a lit lantern when an umpire refused to call a game due to darkness and coaching at third base in rubber boots when an umpire refused to call a game due to rain.

In 2000, author Darryl Brock wrote the historical novel Havana Heat

Havana Heat

Havana Heat is a novel published in 2000 by Darryl Brock. It is a fictionalized story about a real historical figure, Dummy Taylor, a deaf baseball player who played professional baseball in the years 1900-1908.- Plot summary :...

about Taylor's experience in professional baseball. The book won the Dave Moore Award

Dave Moore Award

The baseball journal Elysian Fields Quarterly began awarding the Dave Moore Award in 1999. The honor is given to the “most important” baseball book of the year...

in 2000 as the "most important baseball book" published that year.

Early years

Taylor was born in Oskaloosa, KansasOskaloosa, Kansas

Oskaloosa is a city in and the county seat of Jefferson County, Kansas, United States. As of the 2010 census, the city population was 1,113. Oskaloosa is part of the Topeka, Kansas Metropolitan Statistical Area.-Geography:...

in 1875. He was the son of Arnold B. Taylor, a farmer, and his wife, Emaline (Chatman) Taylor. At the time of the 1880 United States Census, Taylor was living in rural Jefferson County, Kansas

Jefferson County, Kansas

Jefferson County is a county located in Northeast Kansas, in the Central United States. As of the 2010 census, the county population was 19,126. Its county seat is Oskaloosa, and its most populous city is Valley Falls...

with his parents, two older brothers, and two older sisters. Some accounts indicate that Taylor was born deaf. However, at age four, Taylor was not listed as being "deaf and dumb" or otherwise handicapped in the family's U.S. Census record. By age 10, Taylor was living at the Kansas School For the Deaf

Kansas State School For the Deaf

The Kansas School For the Deaf, is a K-12 school, located in downtown Olathe, Kansas. In 1866, it became the first school for the deaf established in the state of Kansas, and today it remains the largest. Originally named the "Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb", the name has been changed several times...

in Olathe, Kansas

Olathe, Kansas

Olathe is a city in and the county seat of Johnson County, Kansas, United States. Located in northeastern Kansas, it is also the fifth most populous city in the state, with a population of 125,872 at the 2010 census. As a suburb of Kansas City, Missouri, Olathe is the fourth-largest city in the...

. He was listed in the 1885 Kansas State Census as a pupil at the Deaf and Dumb Institute.

Taylor continued to live at the Kansas School for the Deaf through his high school years. He was a pitcher for the school baseball team and also participated in boxing. Interviewed in 1942, Taylor recalled that he had dreams as a boy of becoming a great boxer, but his parents objected. At the time of the 1895 Kansas State Census, Taylor was living in Olathe.

Semi-pro and minor league baseball

After leaving the Kansas School for the Deaf, Taylor began playing semi-pro baseball with a team in Nevada, MissouriNevada, Missouri

Nevada is a city in Vernon County, Missouri, United States. The population was 8,327 at the 2011 census. It is the county seat of Vernon County. Nevada is the home of Cottey College, a junior college for women operated by the P.E.O. Sisterhood....

. He then played at Lincoln, Illinois

Lincoln, Illinois

Lincoln is a city in Logan County, Illinois, United States. It is the only town in the United States that was named for Abraham Lincoln before he became president; he practiced law there from 1847 to 1859. First settled in the 1830s, Lincoln is home to three colleges and two prisons. The three...

, and with minor league teams in Wabash

Wabash, Indiana

Wabash is a city in Noble Township, Wabash County, Indiana, United States. The population was 10,666 at the 2010 census. The city is the county seat of Wabash County....

, Crawfordsville

Crawfordsville, Indiana

Crawfordsville is a city in Union Township, Montgomery County, Indiana, United States. As of the 2010 census, the city had a population of 15,915. The city is the county seat of Montgomery County...

, Danville

Danville, Indiana

Danville is a town in Center Township, Hendricks County, Indiana, United States. The population was 9,001at the 2010 census. The town is the county seat of Hendricks County. -History:...

and Terre Haute, Indiana

Terre Haute, Indiana

Terre Haute is a city and the county seat of Vigo County, Indiana, United States, near the state's western border with Illinois. As of the 2010 census, the city had a total population of 60,785 and its metropolitan area had a population of 170,943. The city is the county seat of Vigo County and...

. In 1897, he played for a minor league team in Mattoon, Illinois

Mattoon, Illinois

Mattoon is a city in Coles County, Illinois, United States. The population was 18,555 as of the 2010 census. It is a principal city of the Charleston–Mattoon Micropolitan Statistical Area.Mattoon was the site of the "Mad Gasser" attacks of the 1940s....

. He played for the Shreveport Tigers of the Southern League

Southern League (baseball)

The Southern League is a minor league baseball league which operates in the Southern United States. It is classified a Double-A league. The original league was formed in , and shut down in . A new league, the Southern Association, was formed in , consisting of twelve teams...

in 1898 and 1899.

In 1900, Taylor began the season playing for Albany, New York

Albany, New York

Albany is the capital city of the U.S. state of New York, the seat of Albany County, and the central city of New York's Capital District. Roughly north of New York City, Albany sits on the west bank of the Hudson River, about south of its confluence with the Mohawk River...

. At the time of the U.S. Census in June 1900, Taylor was residing at a boarding house in Albany; his occupation was listed as a printer.

First stint with Giants

In August 1900, Taylor was called up to the major leagues to play for the New York GiantsHistory of the New York Giants (NL)

The history of the New York Giants, before the franchise moved to San Francisco, lasted from 1883 to 1957. It featured five of the franchise's six World Series wins and 17 of its 21 National League pennants...

. He made his major league debut on August 27, 1900. In his first game for the Giants, five Boston players tried to take advantage of Taylor's deafness by trying to steal third base. Interviewed in 1942, Taylor recalled with pride, "I nailed each one. I walked over to (Herman) Long, the last man caught, and let him know by signs I could hear him stealing." Appearing in 11 games for the 1900 Giants, Taylor compiled a 4–3 record with a 2.45 earned run average

Earned run average

In baseball statistics, earned run average is the mean of earned runs given up by a pitcher per nine innings pitched. It is determined by dividing the number of earned runs allowed by the number of innings pitched and multiplying by nine...

(ERA).

In his second season in the major leagues, Taylor was a workhorse for the 1901 Giants

1901 New York Giants season

- Roster :- Starters by position :Note: Pos = Position; G = Games played; AB = At bats; H = Hits; Avg. = Batting average; HR = Home runs; RBI = Runs batted in- Other batters :Note: G = Games played; AB = At bats; H = Hits; Avg...

. He led the National League

National League

The National League of Professional Baseball Clubs, known simply as the National League , is the older of two leagues constituting Major League Baseball, and the world's oldest extant professional team sports league. Founded on February 2, 1876, to replace the National Association of Professional...

with 43 games started and by appearing in a total of 45 games. He also ranked second in the league with 37 complete games, 353⅓ innings pitched, and 1,518 batters faced. Despite maintaining a respectable 3.18 ERA, Taylor played for a weak-hitting Giants team that finished 7th out of 8 teams in hits and runs produced. With the absence of run support, Taylor finished the season with a win-loss record of 18–27. His 27 losses in 1901 is tied for the second most given up by any pitcher in Major League Baseball during the 20th century (trailing Vic Willis

Vic Willis

Victor Gazaway Willis was a Major League Baseball player nicknamed "The Delaware Peach." He was a starting pitcher...

's 29 losses in 1905).

Cleveland Bronchos

In March 1902, Taylor signed for more money with the Cleveland Bronchos of the American LeagueAmerican League

The American League of Professional Baseball Clubs, or simply the American League , is one of two leagues that make up Major League Baseball in the United States and Canada. It developed from the Western League, a minor league based in the Great Lakes states, which eventually aspired to major...

. He recalled that American League teams were "waving big money at us" in the winter before the 1902 season. Taylor appeared in four games for the Bronchos, all as a starter. Despite a 1.59 ERA, Taylor again suffered from a lack of run support and compiled a record of 1–3 in Cleveland.

Second stint with Giants

In May 1902, the Giants sent catcher Frank BowermanFrank Bowerman

Frank Eugene Bowerman was a catcher in Major League Baseball with the Baltimore Orioles, the Pittsburgh Pirates, the New York Giants, and the Boston Doves, as well as a player-manager for the Doves in his last season in professional baseball...

to persuade Taylor to return to the Giants. Bowerman sat in the stands while Taylor was pitching and negotiated the terms of Taylor's return to the Giants by signing. Taylor recalled:

Frank sat in the grandstand and every time I walked out to the pitching mound he kept talking to me with his fingers. I kept shaking my head "No," and Frank kept boosting the money. Soon, I nodded my head "Yes," and that night I was on my way back to New York with Frank.

Taylor appeared in 26 games for the 1902 Giants and had 22 complete games. Taylor's 7–15 record for the 1902 Giants was again the result of playing for a remarkably weak-hitting team, as the 1902 Giants finished in last place in runs, hits and batting average. Even Christy Mathewson

Christy Mathewson

Christopher "Christy" Mathewson , nicknamed "Big Six", "The Christian Gentleman", or "Matty", was an American Major League Baseball right-handed pitcher. He played his entire career in what is known as the dead-ball era...

, who was Taylor's teammate on the 1902 Giants, registered a losing record in 1902 with an ERA (2.12) only marginally better than Taylor.

In 1903, John McGraw

John McGraw

John McGraw may refer to:* John McGraw , , New York lumber tycoon, and one of the founding trustees of Cornell University* John McGraw , , Governor of Washington state from 1893–1897...

took over as the manager of the Giants. McGraw quickly turned the Giants into one of the best teams in the National League, with Taylor, Mathewson, and Iron Man Joe McGinnity as his pitching stars. Taylor had his most successful season in 1904. With strong support from a Giants team that finished first in the National League in runs and hits, Taylor compiled a 21–15 record in 1904. He was among the National League leaders that year with 21 wins (4th), five shutouts (3rd), 1.033 WHIP

Walks plus hits per inning pitched

In baseball statistics, walks plus hits per inning pitched is a sabermetric measurement of the number of baserunners a pitcher has allowed per inning pitched. It is a measure of a pitcher's ability to prevent batters from reaching base...

(5th), 136 strikeouts (6th), and a .991 fielding percentage (2nd).

In 1905, Taylor helped lead the Giants to their second consecutive National League pennant. Taylor appeared in 32 games and compiled a record of 16–9 with a 2.66 ERA. Taylor was scheduled to pitch in the third game of the 1905 World Series

1905 World Series

- Game 1 :Monday, October 9, 1905 at Columbia Park in Philadelphia, PennsylvaniaA pitchers' duel took place between Christy Mathewson and Eddie Plank. Both pitchers got out of jams and were able to shut the offense down. In the Giants top of the fifth, Mathewson singled, but was forced by Roger...

, but the game was cancelled because of rain, and Christy Mathewson was able to pitch with an extra day of rest when the Series resumed. (Mathewson pitched three complete-game shutouts in the 1905 World Series.)

Although the Giants fell short of a third consecutive pennant in 1906, Taylor had another strong year, compiling a 17–9 record and a 2.20 ERA. His 1906 ERA was the lowest on a pitching staff that also included Hall of Fame

National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum is an American history museum and hall of fame, located at 25 Main Street in Cooperstown, New York, operated by private interests serving as the central point for the study of the history of baseball in the United States and beyond, the display of...

rs Christy Mathewson (2.97 ERA) and Iron Man Joe McGinnity (2.25 ERA). Taylor also ranked 6th in the National League with a .654 winning percentage in 1906.

In 1907, Taylor went 11–7 with a 2.42 ERA and a 1.117 WHIP. He pitched his final major league season in 1908, compiling an 8–5 record with a 2.33 ERA.

Minor leagues

In February 1909, Taylor was sold to the Buffalo BisonsBuffalo Bisons

The Buffalo Bisons are a minor league baseball team based in Buffalo, New York. They currently play in the International League and are the Triple-A affiliate of the New York Mets...

in the Eastern League. He won 32 games for Buffalo in 1909 and 1910 and played in the minor leagues from 1909 to 1915. In his final season of organized baseball, he compiled an 18–11 record for the Utica Utes in the New York State League

New York State League

This article refers to the modern New York State League. For the original incarnations of the New York State League see New York State League ...

.

Overall record

In nine seasons in the major leagues, Taylor compiled an overall win-loss record of 116–106 and 767 strikeouts. He threw 237 complete games and 21 shutouts. He had a career ERA of 2.75 and a career WHIP of 1.267.Hearing impairment

Taylor was profoundly deaf and communicated on-field with his teammates in sign languageSign language

A sign language is a language which, instead of acoustically conveyed sound patterns, uses visually transmitted sign patterns to convey meaning—simultaneously combining hand shapes, orientation and movement of the hands, arms or body, and facial expressions to fluidly express a speaker's...

. He is credited with helping to expand and make universal the use of sign language throughout the modern baseball infield, including but not limited to the use of pitching signs. According to Sean Lahman in his biography of Taylor, "The Giants didn't just add Taylor to their roster; they embraced him as a member of the family. Player-manager George Davis

George Davis

George Davis may refer to:*George Davis , Dutch-born American actor*George Davis , American environmental policy analyst*George Davis , British armed robber...

learned sign language and encouraged his players to do the same. John McGraw did likewise when he took over as Giants manager in July 1902." In Lawrence Ritter

Lawrence Ritter

Lawrence S. Ritter was an American writer whose specialties were economics and baseball.Ritter was a professor of economics and finance, and chairman of the Department of Finance at the Graduate School of Business Administration of New York University. He also edited the academic periodical...

's The Glory of Their Times

The Glory of Their Times

The Glory of Their Times: The Story Of The Early Days Of Baseball Told By The Men Who Played It is a book, edited by Lawrence Ritter, telling the stories of early 20th century baseball...

, Taylor's teammate, Fred Snodgrass

Fred Snodgrass

Frederick Carlisle "Snow" Snodgrass was an American center fielder in Major League baseball from 1908 to 1916 for the New York Giants and the Boston Braves. He played under manager John McGraw and with some of the game's early greats, including Christy Mathewson...

, recalled:

We could all read and speak the deaf-and-dumb sign language, because Dummy Taylor took it as an affront if you didn't learn to converse with him. He wanted to be one of us, to be a full-fledged member of the team. If we went to the vaudeville show, he wanted to know what the joke was, and somebody had to tell him. So we all learned. We practiced all the time.

During his eight seasons in Major League Baseball, Taylor's success won acclaim in the deaf press, including The Silent Worker, and he became a role model and hero for the deaf community. An article in The Saturday Evening Post

The Saturday Evening Post

The Saturday Evening Post is a bimonthly American magazine. It was published weekly under this title from 1897 until 1969, and quarterly and then bimonthly from 1971.-History:...

noted that "wherever Taylor goes he will always be visited by scores of the silent fraternity among whom he is regarded as a prodigy."

On May 16, 1902, Taylor pitched against Dummy Hoy

Dummy Hoy

William Ellsworth Hoy , nicknamed "Dummy," was an American center fielder in Major League Baseball who played for several teams from 1888 to 1902, most notably the Cincinnati Reds and two Washington, D.C...

in Cincinnati, Ohio. The occasion was reported to be "the first and only time two deaf professional athletes competed against one another." When Hoy came to bat for the first time, he signed to Taylor, "I'm glad to see you." Hoy collected two hits off Taylor, but Taylor got the win as the Giants beat the Reds

Cincinnati Reds

The Cincinnati Reds are a Major League Baseball team based in Cincinnati, Ohio. They are members of the National League Central Division. The club was established in 1882 as a charter member of the American Association and joined the National League in 1890....

5–3.

Taylor's nickname, "Dummy," was commonly applied to "deaf and dumb" baseball players in the late 19th and early 20th century. Dummy Dundon

Ed Dundon

Edward Joseph Dundon was an American Association pitcher who is credited with being the first deaf player in Major League Baseball history. He pitched for the Columbus Buckeyes of the American Association in 1883 and 1884, with a career record of 9-20 and a 4.25 ERA...

and Dummy Hoy were the first professional baseball players to receive the appellation. Others include Dummy Deegan

Dummy Deegan

William Joseph Deegan was a pitcher in Major League Baseball. He pitched in two games for the 1901 New York Giants.Deegan, nicknamed "Dummy" for being a deaf-mute, was one of three pitchers on the Giants staff with that nickname.-External links:...

, Dummy Leitner

Dummy Leitner

George Michael "Dummy" Leitner was a pitcher in Major League Baseball for two seasons. He played for the Philadelphia Athletics and New York Giants in 1901 and the Cleveland Bronchos and Chicago White Sox in 1902....

, Dummy Lynch

Dummy Lynch

Matthew Daniel "Dummy" Lynch was an American Major League Baseball player. A native of Dallas, Texas, Lynch was a paratrooper in the 82nd Airborne Division during World War II. After the war, he attended Southern Methodist University, where he played both baseball and basketball. He played one...

, Dummy Murphy

Dummy Murphy

Herbert Courtland "Dummy" Murphy was a shortstop in Major League Baseball. He played for the Philadelphia Phillies in 1914.-Career:...

and Dummy Stephenson

Dummy Stephenson

Reuben Crandol "Dummy" Stephenson was an outfielder in Major League Baseball. He played for the Philadelphia Phillies in 1892.-External links:...

. Although he accepted the nickname in his playing days, Taylor noted in a 1945 interview that he and Dummy Hoy did not care for the nickname: "In the old days Hoy and I were called Dummy. It didn't hurt us. It made us fight harder." Taylor's popularity led to an outcry in the deaf press against the use of the nickname. Alexander Pach wrote an editorial in The Silent Worker in which he protested: "The highest salaried deaf man in the United States is the much heralded Dummy Taylor—I say Dummy only to serve to show how contemptible the epithet looks."

Taylor was inducted into the American Athletic Association of the Deaf Hall of Fame in 1953. He was also inducted into the Kansas Sports Hall of Fame in 2006.

Reputation for clowning

Taylor also developed a reputation as the clown on the Giants' team of the 1900s. In April 1905, The New York Times wrote about Taylor's efforts to maintain a light atmosphere in the Giants' locker room. The Times described Taylor's post-shower wrestling matches with Frank Bowerman and his displays of the Japanese martial art, jiu-jitsuJujutsu

Jujutsu , also known as jujitsu, ju-jitsu, or Japanese jiu-jitsu, is a Japanese martial art and a method of close combat for defeating an armed and armored opponent in which one uses no weapon, or only a short weapon....

, adding:

The "Dummy" is always smiling. No matter whether in the dressing room or on the practice field he is the clown of the crowd. If a joke is told he makes Bowerman repeat it to him with his fingers. Then he emits a cacophonous cackle that passes for a laugh. "It is a good thing Taylor can't tell stories," remarked McGraw one morning, "or I never should be able to get any work out of you fellows."

On one occasion, Taylor disagreed with the decision by umpire Bill Klem

Bill Klem

William Joseph Klem, born William Joseph Klimm , known as the "father of baseball umpires", was a National League umpire in Major League Baseball from 1905 to 1941...

not to call the game as darkness fell. Taylor returned to the clubhouse and came back onto the field wearing a fireman's oilskin and holding a lit lantern above his head. Klem yelled at Taylor to get off the field, but Taylor could not hear and continued with his antics until Klem finally called the game.

Honus Wagner

Honus Wagner

-Louisville Colonels:Recognizing his talent, Barrow recommended Wagner to the Louisville Colonels. After some hesitation about his awkward figure, Wagner was signed by the Colonels, where he hit .338 in 61 games....

later wrote about a game in which the Giants were complaining about the umpire's refusal to suspend a game due to rain. Wagner wrote, "So Dummy Taylor, one of the Giant pitchers, went out to the third base coaching lines in his hip boots and a raincoat. Then the umpire did get mad. He chased Taylor out of the park, and it was funny to see Dummy trying to explain to him that he shouldn't be ejected." Taylor later recalled that the umpire, Johnston, "not only chased me, but declared the game forfeited to the other club."

Giants' manager McGraw kept Taylor in the dugout when he wasn't pitching to distract the opposing pitcher. Taylor was able to emit a "rattling shriek" just as the opposing pitcher was about to release a pitch. Teammate Mike Donlin

Mike Donlin

Michael Joseph Donlin was an American outfielder in Major League Baseball who played for the St. Louis Perfectos/Cardinals , Baltimore Orioles , Cincinnati Reds , New York Giants , Boston Rustlers , and Pittsburgh Pirates...

compared the noise to the "crazed shrieking of a jackass." Taylor biographer Sean Lahman wrote: "Umpire Charlie Zimmer once got so irritated with the shrill sound that he ejected Taylor, perhaps the only instance of a deaf player being tossed for being too noisy."

Taylor was also ejected from a baseball game by an umpire "for cursing him out in sign language." According to some accounts, the umpire was Hank O'Day

Hank O'Day

Henry Francis O'Day was an American right-handed pitcher, umpire and manager in Major League Baseball who worked as a National League umpire for 30 years between 1895 and 1927, and was the only person in major league history to appear as a player, manager and umpire. His 3,986 total games as an...

, who knew sign language. After Taylor's tirade, O'Day reportedly stepped in front of the plate and signed the following comments back at Taylor: "Listen, smart guy ... I've spent all my spare time this past week learning your language. You can't call me a blind bat any more. Now, go take a shower ... you're out of the game."

Aside from sign language, Taylor would let it be known that he disagreed with an umpire's call by holding his nose and spinning the second finger of his other hand near his temple, demonstrating his belief that the ump was screwy. In June 1905, umpire Hank O'Day

Hank O'Day

Henry Francis O'Day was an American right-handed pitcher, umpire and manager in Major League Baseball who worked as a National League umpire for 30 years between 1895 and 1927, and was the only person in major league history to appear as a player, manager and umpire. His 3,986 total games as an...

ejected Taylor for hand gestures that he interpreted to be an accusation that "I had wheels in my head." A press account described the scene:

He strode angrily toward O'Day, and the grandstand observed a lightning movement of the hands. Mystic symbol followed mystic symbol, and the crowd kept guessing, what it meant. Suddenly O'Day, too, strode forward and majestically waved Mr. Taylor from the field. Still frantically making rotary movements around his temples, "Dummy" dawdled away."

John McGraw recalled an occasion when he, too, was cursed out by Taylor: "In sign language, Dummy consigned me to the hottest place he could think of—and he didn't mean St. Louis." Taylor was also an accomplished juggler and would often put on "a grand juggling act" in front of the Giants' dugout to amuse the fans.

Later years

After his retirement from baseball, Taylor returned to Olathe and the Kansas State School For the Deaf, where he worked as a teacher and coach. He also served as an umpire from 1915 to 1920, working games for the House of David and Union GiantsGilkerson's Union Giants

-Notable players:*Ted "Double Duty Radcliffe"*John Donaldson-Sources:*...

. As of January 1914, he was the physical director at the Kansas School for the Deaf. At the time of the 1915 Kansas State Census, he was living in Olathe with his wife, Della M. (Ramsey) Taylor. At the time of the 1920 United States Census, Taylor was living at the Kansas School for the Deaf where he was employed as the physical instructor.

Taylor subsequently moved to Iowa where he worked as a coach at the Iowa School for the Deaf. At the time of the 1925 Iowa State Census, Taylor was living at the Iowa School for the Deaf in Lewis Township, Pottawattamie County, Iowa

Pottawattamie County, Iowa

Pottawattamie County is a county located in the U.S. state of Iowa. The population was 93,158 in the 2010 census, an increase from 87,704 in the 2000 census and is the second largest county by area in Iowa. The Pottawattamie county seat is located at Council Bluffs. It is one of three Iowa...

.

In 1927, several newspapers reported that Taylor had died. Taylor issued a statement from his home in Iowa, emphatically denying that he was dead. Taylor's statement resulted in headlines in papers across North America such as, "'Dummy' Taylor Denies being Dead." It turned out that Taylor had been confused with another deaf baseball pitcher, Lyman "Dummy" Taylor.

At the time of the 1930 United States Census, Taylor was still living at the Iowa School for the Deaf. His occupation was listed as a coach, and he was listed as living with his wife, Della M. Taylor, who was a teacher at the school.

Taylor later became employed at the Illinois School for the Deaf in Jacksonville, Illinois

Jacksonville, Illinois

Jacksonville is a city in Morgan County, Illinois, United States. The population was 18,940 at the 2000 census. It is the county seat of Morgan County....

. When he was interviewed in 1942 for a feature story in The Sporting News

The Sporting News

Sporting News is an American-based sports magazine. It was established in 1886, and it became the dominant American publication covering baseball — so much so that it acquired the nickname "The Bible of Baseball"...

, Taylor was employed as a coach and "house father" at the Illinois School for the Deaf. One of Taylor's pupils, Dick Sipek

Dick Sipek

Richard Francis Sipek was a Major League Baseball outfielder, and the only deaf person to play in the majors between Dummy Murphy in and Curtis Pride in . He played in 82 games for the Cincinnati Reds in . He was also the first deaf ballplayer not to carry the nickname "Dummy".-Sources:...

, went on to play baseball for the Cincinnati Reds

Cincinnati Reds

The Cincinnati Reds are a Major League Baseball team based in Cincinnati, Ohio. They are members of the National League Central Division. The club was established in 1882 as a charter member of the American Association and joined the National League in 1890....

.

Having outlived his first wife, Della, who died in 1931, and second wife Lenora Borjquest, Taylor married for the third time to Lina Belle Davis from Little Rock, Arkansas

Little Rock, Arkansas

Little Rock is the capital and the largest city of the U.S. state of Arkansas. The Metropolitan Statistical Area had a population of 699,757 people in the 2010 census...

in August 1941.

Taylor also continued to be involved with professional baseball into the 1950s, umpiring local baseball games and doing scouting work for the Giants.

In August 1958, Taylor died at Our Savior's Hospital in Jacksonville, Illinois. He was buried with his first wife, Della, at Prairie City

Prairie City, Kansas

Prairie City was a town site in southeast Douglas County, Kansas near present-day Baldwin City.-History:Prairie City was founded in 1855 by James Lane, Dr. William Graham, I.F. Greene and Salmon S. Prouty after a dispute between Graham and Henry Barricklow of nearby Palmyra. A post office opened...

Cemetery in Baldwin City, Kansas

Baldwin City, Kansas

Baldwin City is a city in Douglas County, Kansas, United States about south of Lawrence and west of Gardner. As of the 2010 census, the city population was 4,515. It is part of the Lawrence, Kansas Metropolitan Statistical Area...

.

Cultural references

Luther Taylor is used as the narrator and hero of Darryl Brock's fictional account of his later life, Havana HeatHavana Heat

Havana Heat is a novel published in 2000 by Darryl Brock. It is a fictionalized story about a real historical figure, Dummy Taylor, a deaf baseball player who played professional baseball in the years 1900-1908.- Plot summary :...

.