Eric A. Havelock

Encyclopedia

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

classicist

Classics

Classics is the branch of the Humanities comprising the languages, literature, philosophy, history, art, archaeology and other culture of the ancient Mediterranean world ; especially Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome during Classical Antiquity Classics (sometimes encompassing Classical Studies or...

who spent most of his life in Canada and the United States. He was a professor at the University of Toronto

University of Toronto

The University of Toronto is a public research university in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, situated on the grounds that surround Queen's Park. It was founded by royal charter in 1827 as King's College, the first institution of higher learning in Upper Canada...

and was active in the Canadian socialist

Socialism

Socialism is an economic system characterized by social ownership of the means of production and cooperative management of the economy; or a political philosophy advocating such a system. "Social ownership" may refer to any one of, or a combination of, the following: cooperative enterprises,...

movement during the 1930s. In the 1960s and 1970s, he served as chair of the classics departments at both Harvard

Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League university located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States, established in 1636 by the Massachusetts legislature. Harvard is the oldest institution of higher learning in the United States and the first corporation chartered in the country...

and Yale

Yale University

Yale University is a private, Ivy League university located in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701 in the Colony of Connecticut, the university is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States...

. Although he was trained in the turn-of-the-20th-century Oxbridge

Oxbridge

Oxbridge is a portmanteau of the University of Oxford and the University of Cambridge in England, and the term is now used to refer to them collectively, often with implications of perceived superior social status...

tradition of classical studies, which saw Greek intellectual history

Greek philosophy

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BCE and continued through the Hellenistic period, at which point Ancient Greece was incorporated in the Roman Empire...

as an unbroken chain of related ideas, Havelock broke radically with his own teachers and proposed an entirely new model for understanding the classical world, based on a sharp division between literature of the 6th and 5th centuries BC on the one hand, and that of the 4th on the other.

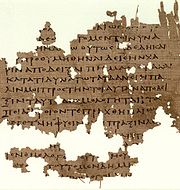

Much of Havelock's work was devoted to addressing a single thesis

Thesis

A dissertation or thesis is a document submitted in support of candidature for an academic degree or professional qualification presenting the author's research and findings...

: that all of Western thought

Western philosophy

Western philosophy is the philosophical thought and work of the Western or Occidental world, as distinct from Eastern or Oriental philosophies and the varieties of indigenous philosophies....

is informed by a profound shift in the kinds of ideas available to the human mind at the point that Greek philosophy

Greek philosophy

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BCE and continued through the Hellenistic period, at which point Ancient Greece was incorporated in the Roman Empire...

converted from an oral

Oral tradition

Oral tradition and oral lore is cultural material and traditions transmitted orally from one generation to another. The messages or testimony are verbally transmitted in speech or song and may take the form, for example, of folktales, sayings, ballads, songs, or chants...

to a literate

Literacy

Literacy has traditionally been described as the ability to read for knowledge, write coherently and think critically about printed material.Literacy represents the lifelong, intellectual process of gaining meaning from print...

form. The idea has been very controversial in classical studies, and has been rejected outright both by many of Havelock's contemporaries and modern classicists. Havelock and his ideas have nonetheless had far-reaching influence, both in classical studies and other academic areas. He and Walter J. Ong

Walter J. Ong

Father Walter Jackson Ong, Ph.D. , was an American Jesuit priest, professor of English literature, cultural and religious historian and philosopher. His major interest was in exploring how the transition from orality to literacy influenced culture and changed human consciousness...

(who was himself strongly influenced by Havelock) essentially founded the amorphous field that studies transitions from orality

Orality

Orality is thought and verbal expression in societies where the technologies of literacy are unfamiliar to most of the population. The study of orality is closely allied to the study of oral tradition...

to literacy, and Havelock has been one of the most frequently cited theorists in that field; as an account of communication, his work profoundly affected the media theories of Harold Innis

Harold Innis

Harold Adams Innis was a Canadian professor of political economy at the University of Toronto and the author of seminal works on media, communication theory and Canadian economic history. The affiliated Innis College at the University of Toronto is named for him...

and Marshall McLuhan

Marshall McLuhan

Herbert Marshall McLuhan, CC was a Canadian educator, philosopher, and scholar—a professor of English literature, a literary critic, a rhetorician, and a communication theorist...

. Havelock's influence has spread beyond the study of the classical world to that of analogous transitions in other times and places.

Education and early academic career

Born in LondonLondon

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

, Havelock grew up in Scotland and enrolled at The Leys School

The Leys School

The Leys School is a co-educational Independent school, located in Cambridge, England, and is a day and boarding school for about 550 pupils aged between 11 and 18 years...

in Cambridge

Cambridge

The city of Cambridge is a university town and the administrative centre of the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It lies in East Anglia about north of London. Cambridge is at the heart of the high-technology centre known as Silicon Fen – a play on Silicon Valley and the fens surrounding the...

at the age of 14. He studied there with W. H. Balgarnie

William Henry Balgarnie

William Henry Balgarnie was a schoolmaster at Elmfield College and The Leys School, and is believed to have been the inspiration for the character Mr Chips in the book Goodbye, Mr...

, a classicist to whom Havelock gives considerable credit. In 1922, Havelock started at Emmanuel College

Emmanuel College, Cambridge

Emmanuel College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge.The college was founded in 1584 by Sir Walter Mildmay on the site of a Dominican friary...

, Cambridge University.

F. M. Cornford

Francis Macdonald Cornford was an English classical scholar and poet.He was educated at St Paul's School and Trinity College, Cambridge, where he was a Fellow from 1899 and held a university teaching post from 1902...

at Cambridge, Havelock began to question the received wisdom about the nature of pre-Socratic philosophy

Pre-Socratic philosophy

Pre-Socratic philosophy is Greek philosophy before Socrates . In Classical antiquity, the Presocratic philosophers were called physiologoi...

and, in particular, about its relationship with Socratic thought

Socrates

Socrates was a classical Greek Athenian philosopher. Credited as one of the founders of Western philosophy, he is an enigmatic figure known chiefly through the accounts of later classical writers, especially the writings of his students Plato and Xenophon, and the plays of his contemporary ...

. In The Literate Revolution in Greece, his penultimate book, Havelock recalls being struck by a discrepancy between the language used by the philosophers he was studying and the heavily Plato

Plato

Plato , was a Classical Greek philosopher, mathematician, student of Socrates, writer of philosophical dialogues, and founder of the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. Along with his mentor, Socrates, and his student, Aristotle, Plato helped to lay the...

nic idiom with which it was interpreted in the standard texts. It was well-known that some of these philosophical texts (Parmenides, Empedocles) were written not only in verse but in the meter of Homer

Homer

In the Western classical tradition Homer , is the author of the Iliad and the Odyssey, and is revered as the greatest ancient Greek epic poet. These epics lie at the beginning of the Western canon of literature, and have had an enormous influence on the history of literature.When he lived is...

, who had recently been identified (still controversially at the time) by Milman Parry

Milman Parry

Milman Parry was a scholar of epic poetry and the founder of the discipline of oral tradition.-Biography:He was born in 1902 and studied at the University of California, Berkeley and at the Sorbonne . A student of the linguist Antoine Meillet at the Sorbonne, Parry revolutionized Homeric studies...

as an oral poet

Oral poetry

Oral poetry can be defined in various ways. A strict definition would include only poetry that is composed and transmitted without any aid of writing. However, the complex relationships between written and spoken literature in some societies can make this definition hard to maintain, and oral...

, but Cornford and other scholars of these early philosophers saw the practice as a fairly insignificant convention leftover from Hesiod

Hesiod

Hesiod was a Greek oral poet generally thought by scholars to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer. His is the first European poetry in which the poet regards himself as a topic, an individual with a distinctive role to play. Ancient authors credited him and...

. Havelock eventually came to the conclusion that the poetic aspects of early philosophy "were matters not of style but of substance," and that such thinkers as Heraclitus

Heraclitus

Heraclitus of Ephesus was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher, a native of the Greek city Ephesus, Ionia, on the coast of Asia Minor. He was of distinguished parentage. Little is known about his early life and education, but he regarded himself as self-taught and a pioneer of wisdom...

and Empedocles

Empedocles

Empedocles was a Greek pre-Socratic philosopher and a citizen of Agrigentum, a Greek city in Sicily. Empedocles' philosophy is best known for being the originator of the cosmogenic theory of the four Classical elements...

actually have more in common even on an intellectual level with Homer than they do with Plato and Aristotle

Aristotle

Aristotle was a Greek philosopher and polymath, a student of Plato and teacher of Alexander the Great. His writings cover many subjects, including physics, metaphysics, poetry, theater, music, logic, rhetoric, linguistics, politics, government, ethics, biology, and zoology...

. However, he did not publicly break from Cornford until many years later.

In 1926 Havelock took his first academic job at Acadia University

Acadia University

Acadia University is a predominantly undergraduate university located in Wolfville, Nova Scotia, Canada with some graduate programs at the master's level and one at the doctoral level...

in Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia is one of Canada's three Maritime provinces and is the most populous province in Atlantic Canada. The name of the province is Latin for "New Scotland," but "Nova Scotia" is the recognized, English-language name of the province. The provincial capital is Halifax. Nova Scotia is the...

, Canada. He married Ellen Parkinson in 1927, and moved on to Victoria College

Victoria University in the University of Toronto

Victoria University is a constituent college of the University of Toronto, founded in 1836 and named for Queen Victoria. It is commonly called Victoria College, informally Vic, after the original academic component that now forms its undergraduate division...

at the University of Toronto

University of Toronto

The University of Toronto is a public research university in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, situated on the grounds that surround Queen's Park. It was founded by royal charter in 1827 as King's College, the first institution of higher learning in Upper Canada...

in 1929. Havelock's scholarly work during this period focused on Latin poetry

Latin poetry

The history of Latin poetry can be understood as the adaptation of Greek models. The verse comedies of Plautus are the earliest Latin literature that has survived, composed around 205-184 BC, yet the start of Latin literature is conventionally dated to the first performance of a play in verse by a...

, particularly Catullus

Catullus

Gaius Valerius Catullus was a Latin poet of the Republican period. His surviving works are still read widely, and continue to influence poetry and other forms of art.-Biography:...

, far from the early Greek philosophy he had worked on at Cambridge. While in Canada Havelock became increasingly involved in politics

Politics of Canada

The politics of Canada function within a framework of parliamentary democracy and a federal system of parliamentary government with strong democratic traditions. Canada is a constitutional monarchy, in which the Monarch is head of state...

. With his fellow academics Frank Underhill

Frank Underhill

Frank Hawkins Underhill, was a Canadian historian, social critic and political thinker.Frank Underhill, born in Stouffville, Ontario, was educated at the University of Toronto and the University of Oxford where he was a member of the Fabian Society...

and Eugene Forsey

Eugene Forsey

Eugene Alfred Forsey, served in the Canadian Senate from 1970 to 1979. He was considered to be one of Canada's foremost constitutional experts.- Biography :...

, Havelock was a cofounder of the League for Social Reconstruction

League for Social Reconstruction

The League for Social Reconstruction was a circle of Canadian socialist intellectuals officially formed in 1932, though it had its beginnings during a camping retreat in 1931. These academics were advocating radical social and economic reforms and political education. Industrialization,...

, an organization of politically active socialist

Socialism

Socialism is an economic system characterized by social ownership of the means of production and cooperative management of the economy; or a political philosophy advocating such a system. "Social ownership" may refer to any one of, or a combination of, the following: cooperative enterprises,...

intellectuals. He and Underhill were also the most outspoken of a group of dissident faculty members at the University.

Havelock's political engagement deepened rapidly. In 1931, after Toronto

Toronto

Toronto is the provincial capital of Ontario and the largest city in Canada. It is located in Southern Ontario on the northwestern shore of Lake Ontario. A relatively modern city, Toronto's history dates back to the late-18th century, when its land was first purchased by the British monarchy from...

police had blocked a public meeting by an organization the police claimed was associated with communists

Communism

Communism is a social, political and economic ideology that aims at the establishment of a classless, moneyless, revolutionary and stateless socialist society structured upon common ownership of the means of production...

, he and Underhill wrote a public letter of protest, calling the action "short-sighted, inexpedient, and intolerable." The letter led to considerable tension between the leadership of the university and the activist professors led by Havelock and Underhill, as well as a sharply critical public reaction. All of the major newspapers in Toronto, along with a number of prominent business leaders, denounced the professors as radical leftists and their behavior as unbecoming of academics.

Though the League for Social Reconstruction began as more of a discussion group than a political party, it became a force in Canadian politics by the mid-1930s. After Havelock joined the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation

Co-operative Commonwealth Federation

The Co-operative Commonwealth Federation was a Canadian political party founded in 1932 in Calgary, Alberta, by a number of socialist, farm, co-operative and labour groups, and the League for Social Reconstruction...

, along with several other members of the League, he was pressured by his superiors at the University to curtail his political activity. He did not, continuing to act as an ally and occasional spokesman for Underhill and other leftist professors. He found himself in trouble again in 1937 after criticizing both the government's and industry's handling of an automotive workers' strike. Despite calls from Ontario

Ontario

Ontario is a province of Canada, located in east-central Canada. It is Canada's most populous province and second largest in total area. It is home to the nation's most populous city, Toronto, and the nation's capital, Ottawa....

officials for his ouster, he was able to remain at Victoria College, but his public reputation was badly damaged.

While at Toronto, Havelock began formulating his theory of orality and literacy, establishing the context of a later movement at the University interested in the critical study of communication, which Donald F. Theall has called the "Toronto School of Communications." Havelock's work was complemented by that of Harold Innis

Harold Innis

Harold Adams Innis was a Canadian professor of political economy at the University of Toronto and the author of seminal works on media, communication theory and Canadian economic history. The affiliated Innis College at the University of Toronto is named for him...

, who was working on the history of media

Media studies

Media studies is an academic discipline and field of study that deals with the content, history and effects of various media; in particular, the 'mass media'. Media studies may draw on traditions from both the social sciences and the humanities, but mostly from its core disciplines of mass...

. The work Havelock and Innis began in the 1930s was the preliminary basis for the influential theories of communication developed by Marshall McLuhan

Marshall McLuhan

Herbert Marshall McLuhan, CC was a Canadian educator, philosopher, and scholar—a professor of English literature, a literary critic, a rhetorician, and a communication theorist...

and Edmund Snow Carpenter

Edmund Snow Carpenter

Edmund "Ted" Snow Carpenter was an anthropologist best known for his work on tribal art and visual media.-Early life:...

in the 1950s.

During World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, Havelock moved away from the socialist organizations he had been associated with, and in 1944 was elected founding president of the Ontario Classical Association

Ontario Classical Association

The Ontario Classical Association was founded in 1944 with Eric A. Havelock as its first president. The association promotes the study of classics through lobbying, scholarships, and colloquia for members. Its membership consists primarily of university and secondary school classics teachers, as...

. One of the association's first activities was organizing a relief effort for Greece

Greece

Greece , officially the Hellenic Republic , and historically Hellas or the Republic of Greece in English, is a country in southeastern Europe....

, which had just been liberated from Nazi control. Havelock continued to write about politics, however, and his political and academic work came together in his ideas about education; he argued for the necessity of an understanding of rhetoric

Rhetoric

Rhetoric is the art of discourse, an art that aims to improve the facility of speakers or writers who attempt to inform, persuade, or motivate particular audiences in specific situations. As a subject of formal study and a productive civic practice, rhetoric has played a central role in the Western...

for the resistance to corporate persuasiveness.

Toward a new theory of Greek intellectual history

Socrates

Socrates was a classical Greek Athenian philosopher. Credited as one of the founders of Western philosophy, he is an enigmatic figure known chiefly through the accounts of later classical writers, especially the writings of his students Plato and Xenophon, and the plays of his contemporary ...

, which was a long-debated issue. Havelock's position, drawn from analyses of Xenophon

Xenophon

Xenophon , son of Gryllus, of the deme Erchia of Athens, also known as Xenophon of Athens, was a Greek historian, soldier, mercenary, philosopher and a contemporary and admirer of Socrates...

and Aristophanes

Aristophanes

Aristophanes , son of Philippus, of the deme Cydathenaus, was a comic playwright of ancient Athens. Eleven of his forty plays survive virtually complete...

as well as Plato

Plato

Plato , was a Classical Greek philosopher, mathematician, student of Socrates, writer of philosophical dialogues, and founder of the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. Along with his mentor, Socrates, and his student, Aristotle, Plato helped to lay the...

himself, was that Plato's presentation of his teacher was largely a fiction, and intended to be a transparent one, whose purpose was to represent indirectly Plato's own ideas. He argued vociferously against the idea associated with John Burnet

John Burnet (classicist)

John Burnet was a Scottish classicist.-Education, Life and Work:Burnet was educated at the Royal High School, Edinburgh, the University of Edinburgh, and Balliol College, Oxford, receiving his M.A. degree in 1887...

, which still had currency at the time, that the basic model for the theory of forms

Theory of Forms

Plato's theory of Forms or theory of Ideas asserts that non-material abstract forms , and not the material world of change known to us through sensation, possess the highest and most fundamental kind of reality. When used in this sense, the word form is often capitalized...

originated with Socrates. Havelock's argument centered around evidence for a historical change in Greek philosophy; Plato, he argued, was fundamentally writing about the ideas of his present, not of the past. Most earlier work in the field had assumed that, since Plato uses Socrates as his mouthpiece, his own philosophical concerns must have been similar to those debated in the Athens

Athens

Athens , is the capital and largest city of Greece. Athens dominates the Attica region and is one of the world's oldest cities, as its recorded history spans around 3,400 years. Classical Athens was a powerful city-state...

of his youth, when Socrates was his teacher. Havelock's contention that Socrates and Plato belonged to different philosophical eras was the first instance of one that would become central to his work: that a basic shift in the kinds of ideas being discussed by intellectuals, and the methods of discussing them, happened at some point between the end of the fifth century BC and the middle of the fourth.

In 1947, Havelock moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts

Cambridge, Massachusetts

Cambridge is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States, in the Greater Boston area. It was named in honor of the University of Cambridge in England, an important center of the Puritan theology embraced by the town's founders. Cambridge is home to two of the world's most prominent...

, to take a position at Harvard University

Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League university located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States, established in 1636 by the Massachusetts legislature. Harvard is the oldest institution of higher learning in the United States and the first corporation chartered in the country...

, where he remained until 1963. He was active in a number of aspects of the University and of the department, of which he became chair; he undertook a translation of and commentary on Aeschylus

Aeschylus

Aeschylus was the first of the three ancient Greek tragedians whose work has survived, the others being Sophocles and Euripides, and is often described as the father of tragedy. His name derives from the Greek word aiskhos , meaning "shame"...

' Prometheus Bound

Prometheus Bound

Prometheus Bound is an Ancient Greek tragedy. In Antiquity, this drama was attributed to Aeschylus, but is now considered by some scholars to be the work of another hand, perhaps one as late as ca. 415 BC. Despite these doubts of authorship, the play's designation as Aeschylean has remained...

for the benefit of his students. He published this translation, with an extended commentary on Prometheus

Prometheus

In Greek mythology, Prometheus is a Titan, the son of Iapetus and Themis, and brother to Atlas, Epimetheus and Menoetius. He was a champion of mankind, known for his wily intelligence, who stole fire from Zeus and gave it to mortals...

and the myth's implications for history, under the title The Crucifixion of Intellectual Man (and then changed it back to Prometheus when the book was republished in the 1960s, saying that the earlier title had "come to seem a bit pretentious"). During this time he began his first major attempt to argue for a division between Platonic or Aristotelian philosophy and what came before. His focus was on political philosophy

Political philosophy

Political philosophy is the study of such topics as liberty, justice, property, rights, law, and the enforcement of a legal code by authority: what they are, why they are needed, what, if anything, makes a government legitimate, what rights and freedoms it should protect and why, what form it...

and, in particular, the beginnings of Greek liberalism

Liberalism

Liberalism is the belief in the importance of liberty and equal rights. Liberals espouse a wide array of views depending on their understanding of these principles, but generally, liberals support ideas such as constitutionalism, liberal democracy, free and fair elections, human rights,...

as introduced by Democritus

Democritus

Democritus was an Ancient Greek philosopher born in Abdera, Thrace, Greece. He was an influential pre-Socratic philosopher and pupil of Leucippus, who formulated an atomic theory for the cosmos....

. In his book The Liberal Temper in Greek Politics, he argued that for Democritus and the liberals, political theory was based on an understanding of "the behaviour of man in a cosmic and historical setting": that is, humanity defined as the poets would define it—measured through its individual actions. Plato and Aristotle were interested in the nature of humanity and, in particular, the idea that human actions might be rooted in inherent qualities rather than consisting of individual choices.

In arguing for a basic heuristic

Heuristic

Heuristic refers to experience-based techniques for problem solving, learning, and discovery. Heuristic methods are used to speed up the process of finding a satisfactory solution, where an exhaustive search is impractical...

split between Plato and the contemporaries of Democritus, Havelock was directly contradicting a very long tradition in philosophy that had painstakingly assembled innumerable connections between Plato and the pre-Socratics, in order to reinforce the position that Plato, as his own dialogues imply, was primarily informed by his teacher Socrates, and that Socrates in turn was a willing participant in a philosophical conversation already several hundred years old (again, with a seeming endorsement from Plato, who shows a young Socrates conversing with and learning from the pre-Socratics Parmenides

Parmenides

Parmenides of Elea was an ancient Greek philosopher born in Elea, a Greek city on the southern coast of Italy. He was the founder of the Eleatic school of philosophy. The single known work of Parmenides is a poem, On Nature, which has survived only in fragmentary form. In this poem, Parmenides...

and Zeno

Zeno of Elea

Zeno of Elea was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher of southern Italy and a member of the Eleatic School founded by Parmenides. Aristotle called him the inventor of the dialectic. He is best known for his paradoxes, which Bertrand Russell has described as "immeasurably subtle and profound".- Life...

in his dialogue the Parmenides—a historical impossibility that might represent figuratively an intellectual rather than direct conversation). The book was intriguing to some philosophers but was poorly received among classicists, with one reviewer calling Havelock's argument for basic difference between Plato and the pre-Socratics "a failure" and his analysis of Plato and Aristotle "distortion."

Preface to Plato

The Liberal Temper makes the argument for the division between Plato and early Greek philosophy without a fully realized account of Havelock's theory of Greek literacy, which he was still developing throughout this period. Rather than attempting once again to explain his distinction between 5th- and 4th-century BC thought in terms of a dissection of the earlier school, Havelock turned, in his 1963 Preface to Plato, to 4th-century BC philosophy itself. He was interested principally in Plato's much debated rejection of poetry in the Republic, in which his fictionalized Socrates argues that poetic mimesisMimesis

Mimesis , from μιμεῖσθαι , "to imitate," from μῖμος , "imitator, actor") is a critical and philosophical term that carries a wide range of meanings, which include imitation, representation, mimicry, imitatio, receptivity, nonsensuous similarity, the act of resembling, the act of expression, and the...

—the representation of life in art—is bad for the soul. Havelock's claim was that the Republic can be used to understand the position of poetry in the "history of the Greek mind." The book is divided into two parts, the first an exploration of oral culture

Orality

Orality is thought and verbal expression in societies where the technologies of literacy are unfamiliar to most of the population. The study of orality is closely allied to the study of oral tradition...

(and what Havelock thinks of as oral thought), and the second an argument for what Havelock calls "The Necessity of Platonism" (the title of Part 2): the intimate relationship between Platonic thought and the development of literacy. Instead of concentrating on the philosophical definitions of key terms, as he had in his book on Democritus, Havelock turned to the Greek language itself, arguing that the meaning of words changed after the full development of written literature to admit a self-reflective subject; even pronoun

Pronoun

In linguistics and grammar, a pronoun is a pro-form that substitutes for a noun , such as, in English, the words it and he...

s, he said, had different functions. The result was a universal shift in what the Greek mind could imagine:

We confront here a change in the Greek language and in the syntax of linguistic usage and in the overtones of certain key words which is part of a larger intellectual revolution, which affected the whole range of the Greek cultural experience . . . Our present business is to connect this discovery with that crisis in Greek culture which saw the replacement of an orally memorised tradition by a quite different system of instruction and education, and which therefore saw the Homeric state of mind give way to the Platonic.

For Havelock, Plato's rejection of poetry was merely the realization of a cultural shift in which he was a participant.

Two distinct phenomena are covered by the shift he observed in Greek culture at the end of the 5th century: the content of thought (in particular the concept of man or of the soul), and the organization of thought. In Homer, Havelock argues, the order of ideas is associative and temporal. The epic's "units of meaning ... are linked associatively to form an episode, but the parts of the episode are greater than the whole." For Plato, on the other hand, the purpose of thought is to arrive at the significance of the whole, to move from the specific to the general. Havelock points out that Plato's syntax

Syntax

In linguistics, syntax is the study of the principles and rules for constructing phrases and sentences in natural languages....

, which he shares with other 4th-century writers, reflects that organization, making smaller ideas subordinate to bigger ideas. Thus, the Platonic theory of forms

Theory of Forms

Plato's theory of Forms or theory of Ideas asserts that non-material abstract forms , and not the material world of change known to us through sensation, possess the highest and most fundamental kind of reality. When used in this sense, the word form is often capitalized...

in itself, Havelock claims, derives from a shift in the organization of the Greek language, and ultimately comes down to a different function for and conception of the noun

Noun

In linguistics, a noun is a member of a large, open lexical category whose members can occur as the main word in the subject of a clause, the object of a verb, or the object of a preposition .Lexical categories are defined in terms of how their members combine with other kinds of...

.

Preface to Plato had a profound impact almost immediately after publication, but an impact that was complex and inconsistent. The book's claims refer to the ideas of a number of different fields: the study (then fairly new) of oral literature as well as Greek philosophy and Greek philology

Philology

Philology is the study of language in written historical sources; it is a combination of literary studies, history and linguistics.Classical philology is the philology of Greek and Classical Latin...

; the book also acknowledges the influence of literary theory

Literary theory

Literary theory in a strict sense is the systematic study of the nature of literature and of the methods for analyzing literature. However, literary scholarship since the 19th century often includes—in addition to, or even instead of literary theory in the strict sense—considerations of...

, particularly structuralism

Structuralism

Structuralism originated in the structural linguistics of Ferdinand de Saussure and the subsequent Prague and Moscow schools of linguistics. Just as structural linguistics was facing serious challenges from the likes of Noam Chomsky and thus fading in importance in linguistics, structuralism...

. The 1960s were a period in which those fields were growing further apart, and the reaction to Preface from each of them was starkly different. Among classicists the response ranged from indifference to derision, with the majority simply questioning the details of Havelock's history of literacy, pointing both to earlier instances of writing than Havelock thinks possible or to later instances of oral influence. Philosophy, particularly Platonic scholarship, was moving in a different direction at the time, and Havelock neither engages nor was cited by the principal movers in that field. However, the book was embraced by literary theorists, students of the transition to literacy, and others in fields as diverse as psychology

Psychology

Psychology is the study of the mind and behavior. Its immediate goal is to understand individuals and groups by both establishing general principles and researching specific cases. For many, the ultimate goal of psychology is to benefit society...

and anthropology

Anthropology

Anthropology is the study of humanity. It has origins in the humanities, the natural sciences, and the social sciences. The term "anthropology" is from the Greek anthrōpos , "man", understood to mean mankind or humanity, and -logia , "discourse" or "study", and was first used in 1501 by German...

.

Ultimately, the book's utility as textual scholarship is limited by Havelock's methods. His account of orality is based almost entirely on Homer, but the history of the Homeric text is not known, which forces Havelock to make claims based on assumptions that cannot fully be tested. Later classicists argue that the poetic nature of Homer's language works against the very arguments Havelock makes about the intellectual nature of oral poetry. What he asserts as a definitive use of language can never be conclusively demonstrated not to be an accident of "metrical convenience." Homerists, like Platonists, found the book to be less than useful for the precise work of their own discipline; many classicists rejected outright Havelock's essential thesis that oral culture predominated through the 5th century. At the same time, though, Havelock's influence, particularly in literary theory, was growing enormously. He is the most cited writer in Walter J. Ong's influential Orality and Literacy other than Ong himself. His work has been cited in studies of orality and literacy in African culture and the implications of modern literacy theory for library science

Library science

Library science is an interdisciplinary or multidisciplinary field that applies the practices, perspectives, and tools of management, information technology, education, and other areas to libraries; the collection, organization, preservation, and dissemination of information resources; and the...

. Preface to Plato has remained continuously in print since its initial publication.

Later years

Shortly after publication of Preface to Plato, Havelock accepted a position as chair of the Classics Department at Yale UniversityYale University

Yale University is a private, Ivy League university located in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701 in the Colony of Connecticut, the university is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States...

. He remained in New Haven for eight years, and then taught briefly as Raymond Distinguished Professor of Classics at the State University of New York at Buffalo

University at Buffalo, The State University of New York

University at Buffalo, The State University of New York, also commonly known as the University at Buffalo or UB, is a public research university and a "University Center" in the State University of New York system. The university was founded by Millard Fillmore in 1846. UB has multiple campuses...

. He retired in 1973 and moved to Poughkeepsie, New York

Poughkeepsie (city), New York

Poughkeepsie is a city in the state of New York, United States, which serves as the county seat of Dutchess County. Poughkeepsie is located in the Hudson River Valley midway between New York City and Albany...

, where his wife Christine Mitchell, whom he had married in 1962, taught at Vassar College

Vassar College

Vassar College is a private, coeducational liberal arts college in the town of Poughkeepsie, New York, in the United States. The Vassar campus comprises over and more than 100 buildings, including four National Historic Landmarks, ranging in style from Collegiate Gothic to International,...

. He was a productive scholar after his retirement, writing three books as well as numerous essays and talks expanding the arguments of Preface to Plato to a generalized argument about the effect of literacy on Greek thought, literature, culture, society, and law.

Increasingly central to Havelock's account of Greek culture in general was his conception of the Greek alphabet

Greek alphabet

The Greek alphabet is the script that has been used to write the Greek language since at least 730 BC . The alphabet in its classical and modern form consists of 24 letters ordered in sequence from alpha to omega...

as a unique entity. He wrote in 1977:

The invention of the Greek alphabet, as opposed to all previous systems, including the PhoenicianPhoenician alphabetThe Phoenician alphabet, called by convention the Proto-Canaanite alphabet for inscriptions older than around 1050 BC, was a non-pictographic consonantal alphabet, or abjad. It was used for the writing of Phoenician, a Northern Semitic language, used by the civilization of Phoenicia...

, constituted an event in the history of human culture, the importance of which has not as yet been fully grasped. Its appearance divides all pre-Greek civilizations from those that are post-Greek.

But his philological concerns now were only a small part of a much larger project to make sense of the nature of the Greek culture itself. His work in this period shows a theoretical

Literary theory

Literary theory in a strict sense is the systematic study of the nature of literature and of the methods for analyzing literature. However, literary scholarship since the 19th century often includes—in addition to, or even instead of literary theory in the strict sense—considerations of...

sophistication far beyond his earlier efforts, extending his theory of literacy toward a theory of culture itself. He said of the Dipylon inscription

Dipylon inscription

The Dipylon inscription is a short text written on an ancient Greek pottery vessel dated to ca. 740 BC. It is famous for being the oldest known samples of the use of the Greek alphabet...

, a poetic line scratched into a vase and the earliest Greek writing known at the time, "Here in this casual act by an unknown hand there is announced a revolution which was destined to change the nature of human culture." It is this larger point about the differences between oral and literate culture that represents Havelock's most influential contribution. Walter J. Ong

Walter J. Ong

Father Walter Jackson Ong, Ph.D. , was an American Jesuit priest, professor of English literature, cultural and religious historian and philosopher. His major interest was in exploring how the transition from orality to literacy influenced culture and changed human consciousness...

, for example, in assessing the significance of non-oral communication in an oral culture, cites Havelock's observation that scientific categories, which are necessary not only for the natural sciences but also for historical and philosophical analysis, depend on writing. These ideas were sketched out in Preface to Plato but became central to Havelock's work from Prologue to Greek Literacy (1971) onward.

In the latter part of his career, Havelock's relentless pursuit of his unvarying thesis led to a lack of interest in addressing opposing viewpoints. In a review of Havelock's The Greek Concept of Justice, a book that attempts to ascribe the most significant ideas in Greek philosophy to his linguistic research, the philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre

Alasdair MacIntyre

Alasdair Chalmers MacIntyre is a British philosopher primarily known for his contribution to moral and political philosophy but known also for his work in history of philosophy and theology...

accuses Havelock of a "brusque refusal to recognize the substance of the case he has to defeat." As a result of this refusal, Havelock seems to have been caught in a conflict of mere contradiction with his opponents, in which without attempt at refutation, he simply asserts repeatedly that philosophy is fundamentally literate in nature, and is countered only with a reminder that, as MacIntyre says, "Socrates wrote no books."

In his last public lecture, which was published posthumously, Havelock addressed the political implications of his own scholarly work. Delivered at Harvard on March 16, 1988, less than three weeks before his death, the lecture is framed principally in opposition to the University of Chicago

University of Chicago

The University of Chicago is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois, USA. It was founded by the American Baptist Education Society with a donation from oil magnate and philanthropist John D. Rockefeller and incorporated in 1890...

philosopher Leo Strauss

Leo Strauss

Leo Strauss was a political philosopher and classicist who specialized in classical political philosophy. He was born in Germany to Jewish parents and later emigrated to the United States...

. Strauss had published a detailed and extensive critique of Havelock's The Liberal Temper in Greek Politics in March, 1959, as "The Liberalism of Classical Political Philosophy" in the journal Review of Metaphysics. (Strauss died 14 years later in 1973, the same year in which Havelock retired.) Havelock's 1988 lecture claims to contain a systematic account of Plato's politics; Havelock argues that Plato's idealism applies a mathematical strictness to politics, countering his old teacher Cornford's assertion that Platonic arguments that morality must be analyzable in arithmetical terms cannot be serious. This way of thinking about politics, Havelock concluded, could not be used as a model for understanding or shaping inherently nonmathematical interactions: "The stuff of human politics is conflict and compromise."

Major works

- The Lyric Genius of Catullus. Oxford: Blackwell, 1939.

- The Crucifixion of Intellectual Man, Incorporating a Fresh Translation into English Verse of the Prometheus Bound of Aeschylus. Boston: Beacon Press, 1950. Reprinted as Prometheus. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1968.

- The Liberal Temper in Greek Politics. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1957.

- Preface to Plato. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1963.

- Prologue to Greek Literacy. Cincinnati: University of Cincinnati Press, 1971.

- The Greek Concept of Justice: From its Shadow in Homer to its Substance in Plato. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1978.

- The Literate Revolution in Greece and its Cultural Consequences. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1981.

- The Muse Learns to Write: Reflections on Orality and Literacy from Antiquity to the Present. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986.

External links

- Chapter-by-chapter redaction of Preface to Plato by Anthony J. Mioni

- Official page for Preface to Plato from the Harvard University PressHarvard University PressHarvard University Press is a publishing house established on January 13, 1913, as a division of Harvard University, and focused on academic publishing. In 2005, it published 220 new titles. It is a member of the Association of American University Presses. Its current director is William P...

. - Guide to the Eric Alfred Havelock Papers at the Yale UniversityYale UniversityYale University is a private, Ivy League university located in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701 in the Colony of Connecticut, the university is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States...

Archives, compiled by Carol King; contains a biography. - "Eric Havelock: Plato and the Transition From Orality to Literacy," part of a series from the Marshall McLuhan Program in Culture and Technology at the University of TorontoUniversity of TorontoThe University of Toronto is a public research university in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, situated on the grounds that surround Queen's Park. It was founded by royal charter in 1827 as King's College, the first institution of higher learning in Upper Canada...

.