Communism

Encyclopedia

Communism is a social

, political and economic

ideology that aims at the establishment of a classless

, moneyless, revolutionary

and stateless

socialist society

structured

upon common ownership

of the means of production

. This movement, in its Marxist-Leninist interpretations, significantly influenced the history of the 20th century, which saw intense rivalry between the "socialist world" (socialist state

s ruled by Communist parties

) and the "western world" (countries with market economies

and Liberal democratic government), culminating in the Cold War

between the Eastern bloc

and the "Free World

".

In Marxist theory

, communism is a specific stage of historical development that inevitably emerges from the development of the productive forces

that leads to a superabundance of material wealth, allowing for distribution based on need

and social relations based on freely associated individuals

. The exact definition of communism varies, and it is often mistakenly, in general political discourse, used interchangeably with socialism

; however, Marxist theory contends that socialism is just a transitional stage on the road to communism. Leninists

revised this theory by introducing the notion of a vanguard party

to lead the proletarian revolution and to hold all political power after the revolution, "in the name of the workers" and with worker participation

, in a transitional stage between capitalism

and socialism.

Communists such as council communists and non-Marxist libertarian communists and anarcho-communist oppose the idea of a vanguard party and a transition stage, and advocate for the construction of full communism to begin immediately upon the abolition of capitalism. There is a very wide range of theories amongst those particular communists in regards to how to build the types of institutions that would replace the various economic engines (such as food distribution, education, and hospitals) as they exist under capitalist systems—or even whether to do so at all. Some of these communists have specific plans for the types of administrative bodies that would replace the current ones, while always qualifying that these bodies would be decentralised

and worker-owned, just as they currently are within the activist movements themselves. Others have no concrete set of post-revolutionary blueprints at all, claiming instead that they simply trust that the world's workers and poor will figure out proper modes of distribution and wide-scale production, and also coordination, entirely on their own, without the need for any structured "replacements" for capitalist state-based

control.

In the modern lexicon of what many sociologists and political commentators refer to as the "political mainstream", communism is often used to refer to the policies of states run by communist parties

, regardless of the practical content of the actual economic system

they may preside over. Examples of this include the policies of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam where the economic system incorporates "doi moi", the People's Republic of China

(PRC, or simply "China") where the economic system incorporates "socialist market economy

", and the economic system of the Soviet Union which was described as "state capitalist" by non-Leninist socialists and later by communists who increasingly opposed the post-Stalin era Soviet model as it progressed over the course of the 20th century (e.g. Maoists, Trotskyists and libertarian communists)—and even at one point by Vladimir Lenin

himself.

In the schema of historical materialism

, communism is the idea of a free society with no division or alienation, where mankind is free from oppression and scarcity. A communist society would have no governments, countries, or class divisions. In Marxist theory

, the dictatorship of the proletariat

is the intermediate system between capitalism

and communism, when the government is in the process of changing the means of ownership from privatism

to collective ownership. In political science

, the term "communism" is sometimes used to refer to communist state

s, a form of government

in which the state

operates under a one-party system

and declares allegiance to Marxism-Leninism

or a derivative thereof.

In modern usage, the word "communism" is still often used to refer to the policies of self-declared socialist governments comprising one-party states which were single legal political party systems operating under centrally planned economies

and a state ownership of the means of production

, with the state, in turn, claiming that it represented the interests of the working class

es. A significant sector of the modern communist movement alleges that these states never made an attempt to transition to a communist society, while others even argue that they never achieved a legitimate socialism. Most of these governments based their ideology on Marxism-Leninism

, but they did not call the system they had set up "communism", nor did they even necessarily claim at all times that the ideology was the sole driving force behind their policies: Mao Zedong

, for example, pursued New Democracy

, and Lenin in the early 1920s enacted war communism

; later, the Vietnamese enacted doi moi, and the Chinese switched to socialism with Chinese characteristics. The governments labeled by other governments as "communist" generally claimed that they had set up a transitional socialist system. This system is sometimes referred to as state socialism

or by other similar names.

"Pure communism" is a term sometimes used to refer to the stage in history after socialism, although just as many communists use simply the term "communism" to refer to that stage. The classless, stateless society that is meant to characterise this communism is one where decisions on what to produce and what policies to pursue are made in the best interests of the whole of society—a sort of 'of, by, and for the working class', rather than a rich class controlling the wealth and everyone else working for them on a wage

basis. In this communism the interests of every member of society is given equal weight to the next, in the practical decision-making process

in both the political and economic spheres of life. Karl Marx, as well as some other communist philosophers, deliberately never provided a detailed description as to how communism would function as a social system, nor the precise ways in which the working class could or should rise up, nor any other material specifics of exactly how to get to communism from capitalism. In the Communist Manifesto, Marx does lay out a 10-point plan advising the redistribution of land and production to begin the transition to communism, but he ensured that even this was very general and all-encompassing. It has always been presumed that Marx intended these theories to read this way specifically so that later theorists in specific situations could adapt communism to their own localities and conditions.

and marginalised by the bourgeoisie

(wealthy class), to overthrow the capitalist system in a wide-ranging social revolution

. The revolution, in the theory of most individuals and groups espousing communist revolution

, usually involves an armed

rebellion

. The revolution espoused can be explained by theorists in many different ways, and usually depends on the environment in which the particular communism theory originates. For example, the Chinese Revolution

involved military combat between the Chinese Red and the Chinese Nationalist Armies

, while the Vietnamese Revolution

was characterised by guerilla warfare between the heavily-backed Vietnam People's Army

and various Western armies, culminating in the Vietnam War

which ended in 1975. Meanwhile, the Cuban Revolution

was essentially a coup

that did not involve intensive wide-scale military conflict between Fulgencio Batista

's soldiers and those of Fidel Castro

and Che Guevara

. In fact, Castro initially did not believe that a vanguard party

was necessary in Cuba's case, a view boosted by Batista's unpopularity at the time of the actual armed conflict between the two sides. Regardless of the specific form a communist revolution takes, its aim is for the working class to replace the exploiter class as the ruling class to establish a society without class divisions, called socialism, as a prelude to attempting to achieve the final stage of communism.

as the original, hunter-gatherer

state of humankind from which it arose. For Marx, only after humanity was capable of producing surplus

, did private property develop. The idea of a classless society first emerged in Ancient Greece

. Plato

in his The Republic described it as a state where people shared all their property, wives, and children: "The private and individual is altogether banished from life and things which are by nature private, such as eyes and ears and hands, have become common, and in some way see and hear and act in common, and all men express praise and fell joy and sorrow on the same occasions."

In the history of Western thought, certain elements of the idea of a society based on common ownership of property can be traced back to ancient times

. Examples include the Spartacus

slave revolt

in Rome. The 5th century Mazdak

movement in what is now Iran

has been described as "communistic" for challenging the enormous privileges of the noble classes and the clergy, criticizing the institution of private property and for striving for an egalitarian society.

At one time or another, various small communist communities existed, generally under the inspiration of Scripture. In the medieval

Christian church

, for example, some monastic

communities and religious order

s shared their land and other property (see Religious

and Christian communism

). These groups often believed that concern with private property

was a distraction from religious service to God and neighbour.

Communist thought has also been traced back to the work of 16th century English writer Thomas More

. In his treatise Utopia

(1516), More portrayed a society based on common ownership

of property, whose rulers administered it through the application of reason. In the 17th century, communist thought surfaced again in England. In England, a Puritan

religious group

known as the "Diggers" advocated the abolition of private ownership of land. Eduard Bernstein

, in his 1895 Cromwell and Communism argued that several groupings in the English Civil War

, especially the Diggers espoused clear communistic, agrarian ideals, and that Oliver Cromwell

's attitude to these groups was at best ambivalent and often hostile. Criticism of the idea of private property continued into the Age of Enlightenment

of the 18th century, through such thinkers as Jean Jacques Rousseau in France. Later, following the upheaval of the French Revolution

, communism emerged as a political doctrine. François Noël Babeuf

, in particular, espoused the goals of common ownership of land and total economic and political equality among citizens.

Various social reformers in the early 19th century founded communities based on common ownership. But unlike many previous communist communities, they replaced the religious emphasis with a rational and philanthropic basis. Notable among them were Robert Owen

, who founded New Harmony

in Indiana (1825), and Charles Fourier

, whose followers organized other settlements in the United States such as Brook Farm

(1841–47). Later in the 19th century, Karl Marx described these social reformers as "utopian socialists

" to contrast them with his program of "scientific socialism

" (a term coined by Friedrich Engels

). Other writers described by Marx as "utopian socialists" included Saint-Simon

.

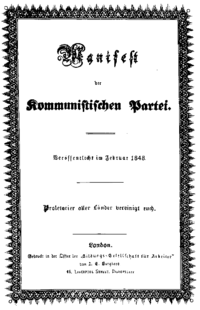

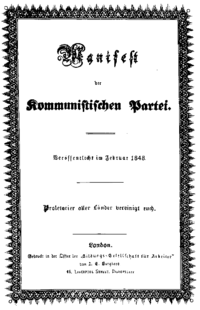

In its modern form, communism grew out of the socialist movement of 19th century Europe. As the Industrial Revolution

advanced, socialist critics blamed capitalism for the misery of the proletariat

—a new class of urban factory workers who laboured under often-hazardous conditions. Foremost among these critics were Marx and his associate Friedrich Engels. In 1848, Marx and Engels offered a new definition of communism and popularized the term in their famous pamphlet The Communist Manifesto

. Engels, who lived in Manchester

, observed the organization of the Chartist

movement (see History of British socialism), while Marx departed from his university comrades to meet the proletariat in France and Germany.

.jpg) In the late 19th century, Russian Marxism developed a distinct character. The first major figure of Russian Marxism was Georgi Plekhanov

In the late 19th century, Russian Marxism developed a distinct character. The first major figure of Russian Marxism was Georgi Plekhanov

. Underlying the work of Plekhanov was the assumption that Russia, less urbanized and industrialized than Western Europe, had many years to go before society would be ready for proletarian revolution to occur, and a transitional period of a bourgeois democratic regime would be required to replace Tsar

ism with a socialist and later communist society. (EB)

In Russia, the 1917 October Revolution

was the first time any party with an avowedly Marxist orientation, in this case the Bolshevik Party

, seized state power

. The assumption of state power by the Bolsheviks generated a great deal of practical and theoretical debate within the Marxist movement. Marx predicted that socialism and communism would be built upon foundations laid by the most advanced capitalist development. Russia, however, was one of the poorest countries in Europe with an enormous, largely illiterate peasantry and a minority of industrial workers. Marx had explicitly stated that Russia might be able to skip the stage of bourgeoisie capitalism. Other socialists also believed that a Russian revolution

could be the precursor of workers' revolutions in the West.

The moderate Menshevik

s opposed Lenin's Bolshevik plan for socialist revolution

before capitalism was more fully developed. The Bolsheviks' successful rise to power was based upon the slogans such as "Peace, bread, and land" which tapped the massive public desire for an end to Russian involvement in the First World War

, the peasants' demand for land reform

, and popular support for the Soviets

.

The usage of the terms "communism" and "socialism" shifted after 1917, when the Bolsheviks changed their name to Communist Party and installed a single party regime devoted to the implementation of socialist policies under Leninism

. The Second International

had dissolved in 1916 over national divisions, as the separate national parties that composed it did not maintain a unified front against the war

, instead generally supporting their respective nation's role. Lenin thus created the Third International (Comintern) in 1919 and sent the Twenty-one Conditions

, which included democratic centralism

, to all European socialist parties

willing to adhere. In France, for example, the majority of the French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO) party split in 1921 to form the French Section of the Communist International

(SFIC). Henceforth, the term "Communism" was applied to the objective of the parties founded under the umbrella of the Comintern. Their program called for the uniting of workers of the world for revolution, which would be followed by the establishment of a dictatorship of the proletariat

as well as the development of a socialist economy

. Ultimately, if their program held, there would develop a harmonious classless society, with the withering away of the state

.

During the Russian Civil War

During the Russian Civil War

(1918–1922), the Bolsheviks nationalized

all productive property and imposed a policy of war communism

, which put factories and railroads under strict government control, collected and rationed food, and introduced some bourgeois management of industry. After three years of war and the 1921 Kronstadt rebellion

, Lenin declared the New Economic Policy

(NEP) in 1921, which was to give a "limited place for a limited time to capitalism." The NEP lasted until 1928, when Joseph Stalin

achieved party leadership, and the introduction of the first Five Year Plan spelled the end of it. Following the Russian Civil War, the Bolsheviks, in 1922, formed the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), or Soviet Union, from the former Russian Empire

.

Following Lenin's democratic centralism, the communist parties were organized on a hierarchical basis, with active cells of members as the broad base; they were made up only of elite cadres approved by higher members of the party as being reliable and completely subject to party discipline

.

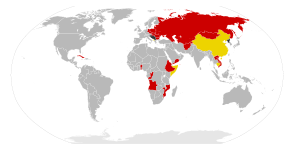

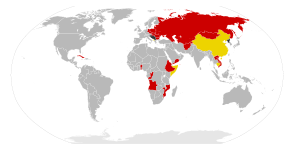

Following World War II

, Communists consolidated power in Central

and Eastern Europe

, and in 1949, the Communist Party of China

(CPC), led by Mao Zedong

, established the People's Republic of China

, which would follow its own ideological path of Communist development following the Sino-Soviet split

. Cuba

, North Korea

, Vietnam

, Laos

, Cambodia

, Angola

, and Mozambique

were among the other countries in the Third World

that adopted or imposed a Communist government at some point. By the early 1980s almost one-third of the world's population lived in Communist state

s, including the former Soviet Union and PRC.

Communist states such as the Soviet Union and PRC succeeded in becoming industrial and technological powers, challenging the capitalists' powers in the arms race

and space race

.

By virtue of the Soviet Union's victory in the Second World War

By virtue of the Soviet Union's victory in the Second World War

in 1945, the Red Army

occupied nations not only in Central

and Eastern Europe

, but also in East Asia

; consequently, communism as a movement spread to many new countries. This expansion of communism both in Europe and Asia gave rise to a few different branches of its own, such as Maoism

.

Communism had been vastly strengthened by the winning of many new nations into the sphere of Soviet influence

and strength in Central and Eastern Europe. Governments modelled on Soviet Communism took power with Soviet assistance in Bulgaria

, Czechoslovakia

, East Germany, Poland

, Hungary

and Romania

. A Communist government was also created under Marshal Tito in Yugoslavia

, but Tito's independent policies led to the expulsion of Yugoslavia

from the Cominform

, which had replaced the Comintern

. Titoism

, a new branch in the world Communist movement, was labelled "deviationist

". Albania

also became an independent Communist nation after World War II.

By 1950, the Chinese Communists

held all of Mainland China

, thus controlling the most populous nation in the world. Other areas where rising Communist strength provoked dissension and in some cases led to actual fighting through conventional and guerrilla warfare

include the Korean War

, Laos

, many nations of the Middle East

and Africa

, and notably succeeded in the case of the Vietnam War

against the military power

of the United States and its allies. With varying degrees of success, Communists attempted to unite with nationalist

and socialist

forces against what they saw as Western

imperialism

in these poor countries.

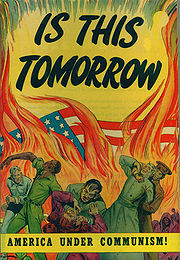

With the exception of the contribution in World War II

by the Soviet Union, China, and the Italian resistance movement

, communism was seen as a rival, and a threat to western democracies and capitalism for most of the 20th century. This rivalry peaked during the Cold War

, as the world's two remaining superpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union, polarized most of the world into two camps of nations. This was characterized in the West as The Free World vs. Behind the Iron Curtain. It supported the spread of their respective economic and political systems (capitalism and communism) and strengthened their military powers. As a result, the camps developed new weapon systems, stockpiled nuclear weapon

s, and competed in space exploration.

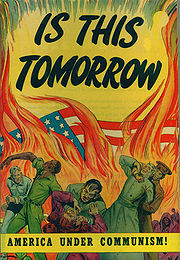

Near the beginning of the Cold War, on February 9, 1950, Senator Joseph McCarthy

from Wisconsin

accused 205 Americans working in the State Department

of being "card-carrying communists". The fear of communism in the U.S. spurred McCarthyism

, aggressive investigations and the red-baiting

, blacklist

ing, jailing and deportation of persons suspected of following communist or other left-wing ideologies. Many famous actors and writers were placed on a blacklist from 1950 to 1954, which meant they would not be hired and would be subject to public disdain.

became leader of the Soviet Union and relaxed central control, in accordance with reform policies of glasnost

(openness) and perestroika

(restructuring). The Soviet Union did not intervene as Poland

, East Germany, Czechoslovakia

, Bulgaria

, Romania

, and Hungary

all abandoned Communist rule by 1990. In 1991, the Soviet Union dissolved

.

By the beginning of the 21st century, states controlled by communist parties under a single-party system include the People's Republic of China

, Cuba

, Laos

, Vietnam

, and informally North Korea

. Communist parties, or their descendant parties, remain politically important in many countries. President Dimitris Christofias

of Cyprus

is a member of the Progressive Party of Working People

, but the country is not run under single-party rule. In South Africa

, the Communist Party is a partner in the ANC

-led government. In India

, communists lead the governments of three states

, with a combined population of more than 115 million. In Nepal

, communists hold a majority in the parliament

. In Brazil, the PCdoB

is a part of the parliamentary coalition led by the ruling democratic socialist Workers' Party and is represented in the executive cabinet

of Dilma Rousseff

.

The People's Republic of China has reassessed many aspects of the Maoist legacy; it, along with Laos, Vietnam, and, to a lesser degree Cuba, has reduced state control of the economy in order to stimulate growth. Chinese economic reform

s started in 1978 under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping

; since then, China has managed to bring down the poverty rate from 53% in the Mao era to just 6% in 2001. The People's Republic of China runs Special Economic Zone

s dedicated to market-oriented enterprise, free from central government

control. Several other communist states have also attempted to implement market-based reforms, including Vietnam.

Theories within Marxism as to why communism in Central and Eastern Europe was not achieved after socialist revolutions pointed to such elements as the pressure of external capitalist states, the relative backwardness of the societies in which the revolutions occurred, and the emergence of a bureaucratic stratum or class that arrested or diverted the transition press in its own interests. (Scott and Marshall, 2005) Marxist critics of the Soviet Union, most notably Trotsky, referred to the Soviet system

Theories within Marxism as to why communism in Central and Eastern Europe was not achieved after socialist revolutions pointed to such elements as the pressure of external capitalist states, the relative backwardness of the societies in which the revolutions occurred, and the emergence of a bureaucratic stratum or class that arrested or diverted the transition press in its own interests. (Scott and Marshall, 2005) Marxist critics of the Soviet Union, most notably Trotsky, referred to the Soviet system

, along with other Communist states, as "degenerated

" or "deformed workers' state

s", arguing that the Soviet system fell far short of Marx's communist ideal and he claimed the working class

was politically dispossessed. The ruling stratum of the Soviet Union was held to be a bureaucratic caste

, but not a new ruling class

, despite their political control. Anarchists who adhere to Participatory economics

claim that the Soviet Union became dominated by powerful intellectual elites who in a capitalist system crown the proletariat's labour on behalf of the bourgeoisie.

Non-Marxists, in contrast, have often applied the term to any society ruled by a communist party and to any party aspiring to create a society similar to such existing nation-states. In the social sciences

, societies ruled by communist parties are distinct for their single party control and their socialist economic bases. While some social and political scientists applied the concept of "totalitarianism

" to these societies, others identified possibilities for independent political activity within them, and stressed their continued evolution up to the point of the dissolution of the Soviet Union and its allies in Central Europe

during the late 1980s and early 1990s.

, the collective philosophies of the German philosophers Karl Marx

. Marxism-Leninism

is the synthesis of Vladimir Lenin

's contributions to Marxism, such as how a revolutionary party should be organised; Trotskyism

is Leon Trotsky

's conception of Marxism, influenced by Lenin, and meanwhile, Maoism

is Mao Zedong

's interpretation of Marxism to suit the conditions of China at that time, and is fairly heavy on the need for agrarian worker support as the engine for the revolution, rather than workers in the urban areas, which were still very small at that point.

Self-identified communists hold a variety of views, including Marxism-Leninism

, Trotskyism

, council communism

, Luxemburgism

, anarchist communism

, Christian communism

, and various currents of left communism

. However, the offshoots of the Marxist-Leninist interpretations of Marxism

are the best-known of these and had been a driving force in international relations

during the last quarter of the 19th century and most of the 20th century up to around 1989 and what historians refer to as "the collapse of communism." However, other forms of communism worldwide continue to exist in the ideologies of various individual labor movement trade union

s worldwide, particularly in Europe

and the Third World

, and also in communist parties

that continue to espouse the ultimate need for communist revolution

.

Most communists today tend to agree that the remaining communist state

s, such as China, Vietnam and especially North Korea

(which has replaced Marxism-Leninism

with Juche

as its official ideology), have nothing to do with communism, whether as practised currently within leftist resistance movements and parties, or in terms of the ideologies and programmes held by those movements.

A diverse range of theories persist amongst prominent globally known people such as Slavoj Zizek

, Michael Parenti

, Alain Badiou

and other radical left

thinkers who proclaim themselves communists; they and others like them are examples of present-day well-known figures in the modern communist movement.

Like other socialists, Marx and Engels

sought an end to capitalism and the systems which they perceived to be responsible for the exploitation of workers. Whereas earlier socialists often favored longer-term social reform

, Marx and Engels believed that popular revolution was all but inevitable, and the only path to socialism and communism.

According to the Marxist argument for communism, the main characteristic of human life in class society

is alienation

; and communism is desirable because it entails the full realization of human freedom. Marx here follows Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel

in conceiving freedom not merely as an absence of restraints but as action with content. According to Marx, communism's outlook on freedom was based on an agent, obstacle, and goal. The agent is the common/working people; the obstacles are class divisions, economic inequalities, unequal life-chances

, and false consciousness; and the goal is the fulfilment of human needs including satisfying work, and fair share of the product.

They believed that communism allowed people to do what they want, but also put humans in such conditions and such relations with one another that they would not wish to exploit, or have any need to. Whereas for Hegel the unfolding of this ethical life in history is mainly driven by the realm of ideas, for Marx, communism emerged from material forces, particularly the development of the means of production

.

Marxism holds that a process of class conflict

and revolutionary struggle will result in victory for the proletariat

and the establishment of a communist society

in which private property and ownership

is abolished over time and the means of production and subsistence belong to the community. (Private property and ownership, in this context, means ownerships of the means of production

, not private possessions). Marx himself wrote little about life under communism, giving only the most general indication as to what constituted a communist society. It is clear that it entails abundance in which there is little limit to the projects that humans may undertake. In the popular slogan that was adopted by the communist movement

, communism was a world in which each gave according to their abilities, and received according to their needs. The German Ideology

(1845) was one of Marx's few writings to elaborate on the communist future:

Marx's lasting vision was to add this vision to a theory of how society was moving in a law-governed way towards communism, and, with some tension, a political theory that explained why revolutionary activity was required to bring it about.

In the late 19th century, the terms "socialism" and "communism" were often used interchangeably. However, Marx and Engels argued that communism would not emerge from capitalism in a fully developed state

, but would pass through a "first phase" in which most productive property was owned in common, but with some class differences remaining. The "first phase" would eventually evolve into a "higher phase" in which class differences were eliminated, and a state was no longer needed. Lenin frequently used the term "socialism" to refer to Marx and Engels' supposed "first phase" of communism and used the term "communism" interchangeably with Marx and Engels' "higher phase" of communism.

These later aspects, particularly as developed by Vladimir Lenin

, provided the underpinning for the mobilizing features of 20th century communist parties.

is the political movement developed by Vladimir Lenin, which has become the foundation for the organizational structure of most major communist parties. Leninists advocate the creation of a vanguard party led by professional revolutionaries in order to lead the working class revolution. Leninists believe that socialism will not arise spontaneously through the natural decay of capitalism and that workers are unable to organize and develop socialist consciousness without the guidance of the Vanguard party. After taking power, Vanguard parties seek to create a socialist state dominated by the Vanguard party in order to direct social development and defend against counterrevolutionary insurrection. The mode of industrial organization championed by Leninism and Marxism-Leninism is the capitalist model of scientific management pioneered by Fredrick Taylor.

Marxism-Leninism

is a version of Leninism merged with classical Marxism

adopted by the Soviet Union and most communist parties across the world today. It shaped the Soviet Union and influenced communist parties worldwide. It was heralded as a possibility of building communism via a massive program of industrialization and collectivisation. Despite the fall of the Soviet Union and the 'Eastern Bloc' (meaning communist countries of Eastern and Central Europe), many communist parties of the world today still lay claim to uphold the Marxist-Leninist banner. Marxism-Leninism expands on Marxists thoughts by bringing the theories to what Lenin and other Communists considered, the age of capitalist imperialism, and a renewed focus on party building, the development of a socialist state

, and democratic centralism as an organizational principle.

Lenin adapted Marx's urban revolution to Russia's agricultural conditions, sparking the "revolutionary nationalism of the poor". The pamphlet What is to be Done? (1902), proposed that the (urban) proletariat

can successfully achieve revolutionary consciousness only under the leadership of a vanguard party

of professional revolutionaries

—who can achieve aims only with internal democratic centralism

in the party; tactical and ideological policy decisions are agreed via democracy, and every member must support and promote the agreed party policy.

To wit, capitalism

can be overthrown only with revolution

—because attempts to reform capitalism from within (Fabianism) and from without (democratic socialism

) will fail because of its inherent contradictions. The purpose of a Leninist revolutionary vanguard party

is the forceful deposition

of the incumbent government; assume power (as agent of the proletariat) and establish a dictatorship of the proletariat

government. Moreover, as the government, the vanguard party must educate

the proletariat—to dispel the societal false consciousness of religion

and nationalism

that are culturally instilled by the bourgeoisie

in facilitating exploitation

. The dictatorship of the proletariat is governed with a de-centralized direct democracy

practised via soviets

(councils) where the workers exercise political power (cf. soviet democracy

); the fifth chapter of State & Revolution, describes it:

The Bolshevik

government was hostile to nationalism, especially to Russian nationalism

, the "Great Russian chauvinism", as an obstacle to establishing the proletarian dictatorship. The revolutionary elements of Leninism—the disciplined vanguard party, a dictatorship of the proletariat, and class war.

was the political system

of the Soviet Union and the countries within the Soviet sphere of influence during the leadership of Joseph Stalin

. The term usually defines the style of a government rather than an ideology. The ideology was officially Marxism-Leninism theory, reflecting that Stalin himself was not a theoretician, in contrast to Marx and Lenin, and prided himself on maintaining the legacy of Lenin as a founding father for the Soviet Union and the future Socialist world. Stalinism is an interpretation of their ideas, and a certain political regime claiming to apply those ideas in ways fitting the changing needs of Soviet society, as with the transition from "socialism at a snail's pace" in the mid-twenties to the rapid industrialization of the Five-Year Plans.

The main contributions of Stalin to communist theory were:

Trotskyism is the branch of Marxism that was developed by Leon Trotsky

Trotskyism is the branch of Marxism that was developed by Leon Trotsky

. It supports the theory of permanent revolution

and world revolution

instead of the two stage theory

and socialism in one country

. It supported proletarian internationalism

and another Communist revolution in the Soviet Union, which, under the leadership of Stalin, Trotsky claimed had become a degenerated worker's state, rather than the dictatorship of the proletariat

.

Trotsky and his supporters organized into the Left Opposition

and their platform became known as Trotskyism

. Stalin eventually succeeded in gaining control of the Soviet regime and Trotskyist attempts to remove Stalin from power resulted in Trotsky's exile from the Soviet Union in 1929. During Trotsky's exile, world communism fractured into two distinct branches: Marxism-Leninism

and Trotskyism

. Trotsky later founded the Fourth International

, a Trotskyist rival to the Comintern

, in 1938.

Trotskyist ideas have continually found a modest echo among political movement

s in some countries in Latin America

and Asia

, especially in Argentina

, Brazil

, Bolivia

and Sri Lanka

. Many Trotskyist organizations are also active in more stable, developed countries in North America

and Western Europe

. Trotsky's politics differed sharply from those of Stalin and Mao, most importantly in declaring the need for an international proletarian revolution (rather than socialism in one country) and unwavering support for a true dictatorship of the proletariat based on democratic principles.

However, as a whole, Trotsky's theories and attitudes were never accepted in worldwide mainstream Communist circles after Trotsky's expulsion, either within or outside of the Soviet bloc

. This remained the case even after the Secret Speech and subsequent events critics claim exposed the fallibility of Stalin.

is the Marxist-Leninist trend of Communism associated with Mao Zedong

and was mostly practiced within China. Khrushchev's reforms heightened ideological differences between China and the Soviet Union, which became increasingly apparent in the 1960s. Parties and groups that supported the Communist Party of China

(CPC) in their criticism against the new Soviet leadership proclaimed themselves as 'anti-revisionist' and denounced the CPSU

and the parties aligned with it as revisionist

"capitalist-roaders." The Sino-Soviet Split resulted in divisions amongst communist parties around the world. Notably, the Party of Labour of Albania sided with the People's Republic of China

. Effectively, the CPC

under Mao's leadership became the rallying forces of a parallel international Communist tendency.

Definitions of Maoism vary. Within the Chinese context, Maoism can refer to Mao's belief in the mobilization of the masses, particularly in large-scale political movements; it can also refer to the egalitarianism

that was seen during Mao's era as opposed to the free-market ideology of Deng Xiaoping

; some scholars additionally define personality cults and political sloganeering as "Maoist" practices. Contemporary Maoists in China criticize the social inequalities created by a capitalist and 'revisionist' Communist party.

Prachanda Path

Prachanda Path

Prachanda Path refers to the ideological line of the Unified Communist Party of Nepal. This thought is an extension of Marxism

, Leninism

and Maoism

, totally based on home-ground politics of Nepal

. The doctrine came into existence after it was realized that the ideology of Marxism, Leninism and Maoism could not be practiced completely as it was done in the past. And an ideology suitable, based on the ground reality of Nepalese politics was adopted by the party.

Hoxhaism

Another variant of anti-revisionist

Marxism-Leninism

appeared after the ideological row

between the Communist Party of China

and the Party of Labour of Albania in 1978. The Albanians rallied a new separate international tendency, which would demarcate itself by a strict defence of the legacy of Joseph Stalin and fierce criticism of virtually all other Communist groupings as revisionism

. Critical of the United States

, the Soviet Union, and China, Enver Hoxha

declared the latter two to be social-imperialist and condemned the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia by withdrawing from the Warsaw Pact

in response. Hoxha declared Albania to be the world's only Marxist-Leninist state after 1978. The Albanians were able to win over a large share of the Maoists, mainly in Latin America

such as the Popular Liberation Army, but also had a significant international following in general. This tendency has occasionally been labelled as 'Hoxhaism' after him.

After the fall of the Communist government in Albania, the pro-Albanian parties are grouped around an international conference

and the publication 'Unity and Struggle'.

Titoism

Elements of Titoism are characterized by policies and practices based on the principle that in each country, the means of attaining ultimate communist goals must be dictated by the conditions of that particular country, rather than by a pattern set in another country. During Tito's era, this specifically meant that the communist goal should be pursued independently of (and often in opposition to) the policies of the Soviet Union. The term was originally meant as a pejorative

, and was labelled by Moscow as a heresy during the period of tensions between the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia known as the Informbiro

period from 1948 to 1955.

Unlike the rest of Central and Eastern Europe, which fell under Stalin's influence post–World War II, Yugoslavia, due to the strong leadership of Marshal Tito

and the fact that the Yugoslav Partisans liberated Yugoslavia with only limited help from the Red Army

, remained independent from Moscow. It became the only country in the Balkans

to resist pressure from Moscow to join the Warsaw Pact

and remained "socialist, but independent" until the collapse of Soviet socialism in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Throughout his time in office, Tito prided himself on Yugoslavia's independence from Russia, with Yugoslavia never accepting full membership of the Comecon

and Tito's open rejection of many aspects of Stalinism as the most obvious manifestations of this.

an communist parties to develop a theory and practice of social transformation that was more relevant in a Western European democracy and less aligned to the influence or control of the Soviet Union. Parties such as the Italian Communist Party

(PCI), the French Communist Party

(PCF), and the Communist Party of Spain (PCE), were politically active and electorally significant in their respective countries).

The main theoretical foundation of Eurocommunism was Antonio Gramsci

's writing about Marxist theory which questioned the sectarianism of the Left and encouraged communist parties to develop social alliances to win hegemonic

support for social reforms. Eurocommunist parties expressed their fidelity to democratic

institutions more clearly than before and attempted to widen their appeal by embracing public sector

middle-class workers, new social movements

such as feminism

and gay liberation

and more publicly questioning the Soviet Union. Early inspirations can also be found in the Austromarxism

and its seeking of a "third" democratic "way" to socialism.

aspects of Marxism

. Early currents of libertarian Marxism, known as left communism

, emerged in opposition to Marxism–Leninism and its derivatives, such as Stalinism

, Maoism

, and Trotskyism

. Libertarian Marxism is also critical of reformist positions, such as those held by social democrats. Libertarian Marxist currents often draw from Marx and Engels' later works, specifically the Grundrisse

and The Civil War in France

; emphasizing the Marxist belief in the ability of the working class

to forge its own destiny without the need for a revolutionary party or state

to mediate or aid its liberation. Along with anarchism

, Libertarian Marxism is one of the main currents of libertarian socialism

.

Libertarian Marxism includes such currents as Luxemburgism

, council communism

, left communism

, Socialisme ou Barbarie

, the Johnson-Forest tendency

, world socialism, Lettrism

/Situationism and operaismo/autonomism

, and New Left

. Libertarian Marxism has often had a strong influence on both post-left and social anarchists

. Notable theorists of libertarian Marxism have included Anton Pannekoek, Raya Dunayevskaya

, CLR James, Antonio Negri

, Cornelius Castoriadis

, Maurice Brinton

, Guy Debord

, Daniel Guérin

, Ernesto Screpanti

and Raoul Vaneigem

.

and the Netherlands

in the 1920s. Its primary organization was the Communist Workers Party of Germany

(KAPD). Council communism continues today as a theoretical and activist position within both left-wing Marxism

and libertarian socialism

.

The central argument of council communism, in contrast to those of social democracy

and Leninist

Communism, is that democratic workers' councils arising in the factories and municipalities are the natural form of working class organisation and governmental power. This view is opposed to both the reformist and the Leninist ideologies

, with their stress on, respectively, parliament

s and institutional

government (i.e., by applying social reforms), on the one hand, and vanguard parties

and participative democratic centralism

on the other).

The core principle of council communism is that the government

and the economy

should be managed by workers' councils composed of delegate

s elected at workplaces and recallable

at any moment. As such, council communists oppose state-run

authoritarian

"State socialism

"/"State capitalism

". They also oppose the idea of a "revolutionary party", since council communists believe that a revolution led by a party will necessarily produce a party dictatorship. Council communists support a worker's democracy, which they want to produce through a federation of workers' councils.

s at certain periods, from a position that is asserted to be more authentically Marxist

and proletarian

than the views of Leninism

held by the Communist International

after its first and during its second congress.

Left Communists see themselves to the left of Leninists (whom they tend to see as 'left of capital', not socialist

s), anarchist communists

(some of whom they consider internationalist socialists) as well as some other revolutionary socialist tendencies (for example De Leonists

, who they tend to see as being internationalist socialists only in limited instances).

Although she died before left communism became a distinct tendency, Rosa Luxemburg

has heavily influenced most left communists, both politically and theoretically. Proponents of left communism have included Amadeo Bordiga

, Herman Gorter

, Anton Pannekoek

, Otto Rühle

, Karl Korsch

, Sylvia Pankhurst

and Paul Mattick

.

Prominent left communist groups existing today include the International Communist Party

, the International Communist Current

and the Internationalist Communist Tendency.

wildcat strikes of May 1968 in France.

With their ideas rooted in Marxism

and the 20th century European artistic avant-garde

s, they advocated experiences of life being alternative to those admitted by the capitalist order

, for the fulfillment of human primitive desires and the pursuing of a superior passional quality. For this purpose they suggested and experimented with the construction of situations, namely the setting up of environments favorable for the fulfillment of such desires. Using methods drawn from the arts, they developed a series of experimental fields of study for the construction of such situations, like unitary urbanism

and psychogeography

.

They fought against the main obstacle on the fulfillment of such superior passional living, identified by them in advanced capitalism

. Their theoretical work peaked on the highly influential book The Society of the Spectacle

by Guy Debord

. Debord argued in 1967 that spectacular features like mass media

and advertising

have a central role in an advanced capitalist society, which is to show a fake reality in order to mask the real capitalist degradation of human life. To overthrow such a system, the Situationist International supported the May '68 revolts, and asked the workers to occupy the factories

and to run them with direct democracy

, through workers' councils composed by instantly revocable delegates.

After publishing in the last issue of the magazine an analysis of the May 1968 revolts, and the strategies that will need to be adopted in future revolutions, the SI was dissolved in 1972.

. As an identifiable theoretical system it first emerged in Italy in the 1960s

from workerist (operaismo) communism. Later, post-Marxist

and anarchist tendencies became significant after influence from the Situationists, the failure of Italian far-left movements in the 1970s, and the emergence of a number of important theorists including Antonio Negri

, who had contributed to the 1969 founding of Potere Operaio

, Mario Tronti, Paolo Virno

, etc.

Through translations made available by Danilo Montaldi and others, the Italian autonomists drew upon previous activist research in the United States by the Johnson-Forest Tendency

and in France by the group Socialisme ou Barbarie

.

It influenced the German and Dutch Autonomen, the worldwide Social Centre movement, and today is influential in Italy, France, and to a lesser extent the English-speaking countries. Those who describe themselves as autonomists now vary from Marxists to post-structuralists

and anarchists. The Autonomist Marxist and Autonomen movements provided inspiration to some on the revolutionary left in English speaking countries, particularly among anarchists, many of whom have adopted autonomist tactics. Some English-speaking anarchists even describe themselves as Autonomists. The Italian operaismo movement also influenced Marxist academics such as Harry Cleaver

, John Holloway

, Steve Wright, and Nick Dyer-Witheford.

, but non-Marxist versions of communism (such as Christian communism

and anarchist communism

) also exist.

Anarchist communism (also known as libertarian communism) is a theory of anarchism

Anarchist communism (also known as libertarian communism) is a theory of anarchism

which advocates the abolition of the state

, private property

, and capitalism

in favour of common ownership

of the means of production

, direct democracy

and a horizontal network of voluntary association

s and workers' council

s with production and consumption based on the guiding principle: "from each according to his ability, to each according to his need

".

Anarcho-communism differs from marxism rejecting its view about the need for a State Socialism phase before building communism. The main anarcho-communist theorist Peter Kropotkin

argued "that a revolutionary society should “transform itself immediately into a communist society,”, that is, should go immediately into what Marx had regarded as the “more advanced,” completed, phase of communism." In this way it tries to avoid the reappearence of "class divisions and the need for a state to oversee everything".

Some forms of anarchist communism such as insurrectionary anarchism

are egoist

and strongly influenced by radical individualism

, believing that anarchist communism does not require a communitarian nature at all. Most anarcho-communists view anarcho-communism as a way of reconciling the opposition between the individual and society

To date in human history, the best known examples of an anarchist communist society, established around the ideas as they exist today, that received worldwide attention and knowledge in the historical canon, are the anarchist territories during the Spanish Revolution

and the Free Territory during the Russian Revolution. Through the efforts and influence of the Spanish Anarchists during the Spanish Revolution

within the Spanish Civil War

, starting in 1936 anarchist communism existed in most of Aragon, parts of the Levante and Andalusia, as well as in the stronghold of Anarchist Catalonia

before being brutally crushed by the combined forces of the authoritarian regime that won the war, Hitler, Mussolini, Spanish Communist Party repression (backed by the USSR) as well as economic and armaments blockades from the capitalist countries and the Spanish Republic itself. During the Russian Revolution, anarchists such as Nestor Makhno

worked to create and defend—through the Revolutionary Insurrectionary Army of Ukraine

—anarchist communism in the Free Territory of the Ukraine from 1919 before being conquered by the Bolsheviks in 1921.

is a form of religious communism centred on Christianity. It is a theological and political theory based upon the view that the teachings of Jesus Christ

urge Christians to support communism as the ideal social system

. Christian communists trace the origins of their practice to teachings in the New Testament

, such as this one from Acts of the Apostles

at chapter 2 and verses 42, 44, and 45:

Christian communism can be seen as a radical form of Christian socialism

. Also, because many Christian communists have formed independent stateless communes in the past, there is also a link between Christian communism and Christian anarchism

. Christian communists may not agree with various parts of Marxism

, but they share some of the political goals of Marxists, for example replacing capitalism with socialism

, which should in turn be followed by communism at a later point in the future. However, Christian communists sometimes disagree with Marxists (and particularly with Leninists

) on the way a socialist or communist society should be organized.

, slow or stagnant technological advance, reduced incentives, reduced prosperity, feasibility, and its social and political effects.

Part of this criticism extends to the policies adopted by one-party states ruled by communist parties (known as "communist state

s"). Some scholars are specially focused on their human rights

records which are claimed to be responsible for famines, purges and warfare resulting in deaths far in excess of previous empires, capitalist or other regimes. The Council of Europe

in Resolution 1481

and international declarations such as the Prague Declaration on European Conscience and Communism

and the Declaration on Crimes of Communism

have condemned some of the actions that resulted in these deaths as crimes.

Stéphane Courtois

argues that Communism and National Socialism are slightly different totalitarian systems, and that communism is responsible for the murder of almost 100 million people in the 20th century, but two of the main Black Books contributors, Nicolas Werth and Jean-Louis Margolin, disagreed and publicly disassociated themselves from Courtois's statements.

Social

The term social refers to a characteristic of living organisms...

, political and economic

Economy

An economy consists of the economic system of a country or other area; the labor, capital and land resources; and the manufacturing, trade, distribution, and consumption of goods and services of that area...

ideology that aims at the establishment of a classless

Classless society

Classless society refers to a society in which no one is born into a social class. Such distinctions of wealth, income, education, culture, or social network might arise and would only be determined by individual experience and achievement in such a society.Since these distinctions are difficult to...

, moneyless, revolutionary

Revolutionary

A revolutionary is a person who either actively participates in, or advocates revolution. Also, when used as an adjective, the term revolutionary refers to something that has a major, sudden impact on society or on some aspect of human endeavor.-Definition:...

and stateless

Stateless society

A stateless society is a society that is not governed by a state. In stateless societies, there is little concentration of authority; most positions of authority that do exist are very limited in power and are generally not permanently held positions; and social bodies that resolve disputes through...

socialist society

Socialist society

Socialist society may refer to one of the following.*A society based on socialism; inclusive collaborative decision-making*The societies of the Communist states*Socialist Society; a periodical*Socialist society...

structured

Base and superstructure

In Marxist theory, human society consists of two parts: the base and superstructure; the base comprehends the forces and relations of production — employer-employee work conditions, the technical division of labour, and property relations — into which people enter to produce the necessities and...

upon common ownership

Common ownership

Common ownership is a principle according to which the assets of an enterprise or other organization are held indivisibly rather than in the names of the individual members or by a public institution such as a governmental body. It is therefore in contrast to public ownership...

of the means of production

Means of production

Means of production refers to physical, non-human inputs used in production—the factories, machines, and tools used to produce wealth — along with both infrastructural capital and natural capital. This includes the classical factors of production minus financial capital and minus human capital...

. This movement, in its Marxist-Leninist interpretations, significantly influenced the history of the 20th century, which saw intense rivalry between the "socialist world" (socialist state

Socialist state

A socialist state generally refers to any state constitutionally dedicated to the construction of a socialist society. It is closely related to the political strategy of "state socialism", a set of ideologies and policies that believe a socialist economy can be established through government...

s ruled by Communist parties

Communist party

A political party described as a Communist party includes those that advocate the application of the social principles of communism through a communist form of government...

) and the "western world" (countries with market economies

Market economy

A market economy is an economy in which the prices of goods and services are determined in a free price system. This is often contrasted with a state-directed or planned economy. Market economies can range from hypothetically pure laissez-faire variants to an assortment of real-world mixed...

and Liberal democratic government), culminating in the Cold War

Cold War

The Cold War was the continuing state from roughly 1946 to 1991 of political conflict, military tension, proxy wars, and economic competition between the Communist World—primarily the Soviet Union and its satellite states and allies—and the powers of the Western world, primarily the United States...

between the Eastern bloc

Eastern bloc

The term Eastern Bloc or Communist Bloc refers to the former communist states of Eastern and Central Europe, generally the Soviet Union and the countries of the Warsaw Pact...

and the "Free World

Free World

The Free World is a Cold War-era term often used to describe states not under the rule of the Soviet Union, its Eastern European allies, China, Vietnam, Cuba, and other communist nations. The term often referred to states such as the United States, Canada, and Western European states such as the...

".

In Marxist theory

Marxism

Marxism is an economic and sociopolitical worldview and method of socioeconomic inquiry that centers upon a materialist interpretation of history, a dialectical view of social change, and an analysis and critique of the development of capitalism. Marxism was pioneered in the early to mid 19th...

, communism is a specific stage of historical development that inevitably emerges from the development of the productive forces

Productive forces

Productive forces, "productive powers" or "forces of production" [in German, Produktivkräfte] is a central idea in Marxism and historical materialism....

that leads to a superabundance of material wealth, allowing for distribution based on need

From each according to his ability, to each according to his need

From each according to his ability, to each according to his need is a slogan popularised by Karl Marx in his 1875 Critique of the Gotha Program. In German, "Jeder nach seinen Fähigkeiten, jedem nach seinen Bedürfnissen!"...

and social relations based on freely associated individuals

Free association (communism and anarchism)

In the anarchist, Marxist and socialist sense, free association is a kind of relation between individuals where there is no state, social class or authority, in a society that had abolished the private property of means of production...

. The exact definition of communism varies, and it is often mistakenly, in general political discourse, used interchangeably with socialism

Socialism

Socialism is an economic system characterized by social ownership of the means of production and cooperative management of the economy; or a political philosophy advocating such a system. "Social ownership" may refer to any one of, or a combination of, the following: cooperative enterprises,...

; however, Marxist theory contends that socialism is just a transitional stage on the road to communism. Leninists

Leninism

In Marxist philosophy, Leninism is the body of political theory for the democratic organisation of a revolutionary vanguard party, and the achievement of a direct-democracy dictatorship of the proletariat, as political prelude to the establishment of socialism...

revised this theory by introducing the notion of a vanguard party

Vanguard party

A vanguard party is a political party at the forefront of a mass action, movement, or revolution. The idea of a vanguard party has its origins in the Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels...

to lead the proletarian revolution and to hold all political power after the revolution, "in the name of the workers" and with worker participation

Participatory democracy

Participatory Democracy, also known as Deliberative Democracy, Direct Democracy and Real Democracy , is a process where political decisions are made directly by regular people...

, in a transitional stage between capitalism

Capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system that became dominant in the Western world following the demise of feudalism. There is no consensus on the precise definition nor on how the term should be used as a historical category...

and socialism.

Communists such as council communists and non-Marxist libertarian communists and anarcho-communist oppose the idea of a vanguard party and a transition stage, and advocate for the construction of full communism to begin immediately upon the abolition of capitalism. There is a very wide range of theories amongst those particular communists in regards to how to build the types of institutions that would replace the various economic engines (such as food distribution, education, and hospitals) as they exist under capitalist systems—or even whether to do so at all. Some of these communists have specific plans for the types of administrative bodies that would replace the current ones, while always qualifying that these bodies would be decentralised

Décentralisation

Décentralisation is a french word for both a policy concept in French politics from 1968-1990, and a term employed to describe the results of observations of the evolution of spatial economic and institutional organization of France....

and worker-owned, just as they currently are within the activist movements themselves. Others have no concrete set of post-revolutionary blueprints at all, claiming instead that they simply trust that the world's workers and poor will figure out proper modes of distribution and wide-scale production, and also coordination, entirely on their own, without the need for any structured "replacements" for capitalist state-based

Nation-state

The nation state is a state that self-identifies as deriving its political legitimacy from serving as a sovereign entity for a nation as a sovereign territorial unit. The state is a political and geopolitical entity; the nation is a cultural and/or ethnic entity...

control.

In the modern lexicon of what many sociologists and political commentators refer to as the "political mainstream", communism is often used to refer to the policies of states run by communist parties

Communist party

A political party described as a Communist party includes those that advocate the application of the social principles of communism through a communist form of government...

, regardless of the practical content of the actual economic system

Economic system

An economic system is the combination of the various agencies, entities that provide the economic structure that defines the social community. These agencies are joined by lines of trade and exchange along which goods, money etc. are continuously flowing. An example of such a system for a closed...

they may preside over. Examples of this include the policies of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam where the economic system incorporates "doi moi", the People's Republic of China

People's Republic of China

China , officially the People's Republic of China , is the most populous country in the world, with over 1.3 billion citizens. Located in East Asia, the country covers approximately 9.6 million square kilometres...

(PRC, or simply "China") where the economic system incorporates "socialist market economy

Socialist market economy

The socialist market economy or socialist market economy with Chinese characteristics is the official term used to refer to the economic system of the People's Republic of China after the reforms of Deng Xiaoping. It is also referred to as socialism with Chinese characteristics...

", and the economic system of the Soviet Union which was described as "state capitalist" by non-Leninist socialists and later by communists who increasingly opposed the post-Stalin era Soviet model as it progressed over the course of the 20th century (e.g. Maoists, Trotskyists and libertarian communists)—and even at one point by Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Lenin was a Russian Marxist revolutionary and communist politician who led the October Revolution of 1917. As leader of the Bolsheviks, he headed the Soviet state during its initial years , as it fought to establish control of Russia in the Russian Civil War and worked to create a...

himself.

Etymology and terminology

Communism comes from the Latin word communis, which means "shared" or "belong to all".In the schema of historical materialism

Historical materialism

Historical materialism is a methodological approach to the study of society, economics, and history, first articulated by Karl Marx as "the materialist conception of history". Historical materialism looks for the causes of developments and changes in human society in the means by which humans...

, communism is the idea of a free society with no division or alienation, where mankind is free from oppression and scarcity. A communist society would have no governments, countries, or class divisions. In Marxist theory

Marxist philosophy

Marxist philosophy or Marxist theory are terms that cover work in philosophy that is strongly influenced by Karl Marx's materialist approach to theory or that is written by Marxists...

, the dictatorship of the proletariat

Dictatorship of the proletariat

In Marxist socio-political thought, the dictatorship of the proletariat refers to a socialist state in which the proletariat, or the working class, have control of political power. The term, coined by Joseph Weydemeyer, was adopted by the founders of Marxism, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, in the...

is the intermediate system between capitalism

Capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system that became dominant in the Western world following the demise of feudalism. There is no consensus on the precise definition nor on how the term should be used as a historical category...

and communism, when the government is in the process of changing the means of ownership from privatism

Privatism

Privatism is a generic term describing any belief that people have a right to the private ownership of certain things. There are many degrees of privatism, from the advocacy of limited private property over specific kinds of items to the advocacy of unrestricted private property over everything;...

to collective ownership. In political science

Political science

Political Science is a social science discipline concerned with the study of the state, government and politics. Aristotle defined it as the study of the state. It deals extensively with the theory and practice of politics, and the analysis of political systems and political behavior...

, the term "communism" is sometimes used to refer to communist state

Communist state

A communist state is a state with a form of government characterized by single-party rule or dominant-party rule of a communist party and a professed allegiance to a Leninist or Marxist-Leninist communist ideology as the guiding principle of the state...

s, a form of government

Form of government

A form of government, or form of state governance, refers to the set of political institutions by which a government of a state is organized. Synonyms include "regime type" and "system of government".-Empirical and conceptual problems:...

in which the state

State (polity)

A state is an organized political community, living under a government. States may be sovereign and may enjoy a monopoly on the legal initiation of force and are not dependent on, or subject to any other power or state. Many states are federated states which participate in a federal union...

operates under a one-party system

Single-party state

A single-party state, one-party system or single-party system is a type of party system government in which a single political party forms the government and no other parties are permitted to run candidates for election...

and declares allegiance to Marxism-Leninism

Marxism-Leninism

Marxism–Leninism is a communist ideology, officially based upon the theories of Marxism and Vladimir Lenin, that promotes the development and creation of a international communist society through the leadership of a vanguard party over a revolutionary socialist state that represents a dictatorship...

or a derivative thereof.

In modern usage, the word "communism" is still often used to refer to the policies of self-declared socialist governments comprising one-party states which were single legal political party systems operating under centrally planned economies

Planned economy

A planned economy is an economic system in which decisions regarding production and investment are embodied in a plan formulated by a central authority, usually by a government agency...

and a state ownership of the means of production

Means of production

Means of production refers to physical, non-human inputs used in production—the factories, machines, and tools used to produce wealth — along with both infrastructural capital and natural capital. This includes the classical factors of production minus financial capital and minus human capital...

, with the state, in turn, claiming that it represented the interests of the working class

Working class

Working class is a term used in the social sciences and in ordinary conversation to describe those employed in lower tier jobs , often extending to those in unemployment or otherwise possessing below-average incomes...

es. A significant sector of the modern communist movement alleges that these states never made an attempt to transition to a communist society, while others even argue that they never achieved a legitimate socialism. Most of these governments based their ideology on Marxism-Leninism

Marxism-Leninism

Marxism–Leninism is a communist ideology, officially based upon the theories of Marxism and Vladimir Lenin, that promotes the development and creation of a international communist society through the leadership of a vanguard party over a revolutionary socialist state that represents a dictatorship...

, but they did not call the system they had set up "communism", nor did they even necessarily claim at all times that the ideology was the sole driving force behind their policies: Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong, also transliterated as Mao Tse-tung , and commonly referred to as Chairman Mao , was a Chinese Communist revolutionary, guerrilla warfare strategist, Marxist political philosopher, and leader of the Chinese Revolution...

, for example, pursued New Democracy

New Democracy

New Democracy or the New Democratic Revolution is a Maoist concept based on Mao Zedong's "Bloc of Four Social Classes" theory during post-revolutionary China which argues that democracy in China will take a decisively distinct path from either the liberal capitalist and/or parliamentary democratic...

, and Lenin in the early 1920s enacted war communism

War communism

War communism or military communism was the economic and political system that existed in Soviet Russia during the Russian Civil War, from 1918 to 1921...

; later, the Vietnamese enacted doi moi, and the Chinese switched to socialism with Chinese characteristics. The governments labeled by other governments as "communist" generally claimed that they had set up a transitional socialist system. This system is sometimes referred to as state socialism

State socialism

State socialism is an economic system with limited socialist characteristics, such as public ownership of major industries, remedial measures to benefit the working class, and a gradual process of developing socialism through government policy...

or by other similar names.

"Pure communism" is a term sometimes used to refer to the stage in history after socialism, although just as many communists use simply the term "communism" to refer to that stage. The classless, stateless society that is meant to characterise this communism is one where decisions on what to produce and what policies to pursue are made in the best interests of the whole of society—a sort of 'of, by, and for the working class', rather than a rich class controlling the wealth and everyone else working for them on a wage

Wage

A wage is a compensation, usually financial, received by workers in exchange for their labor.Compensation in terms of wages is given to workers and compensation in terms of salary is given to employees...

basis. In this communism the interests of every member of society is given equal weight to the next, in the practical decision-making process

Decision making

Decision making can be regarded as the mental processes resulting in the selection of a course of action among several alternative scenarios. Every decision making process produces a final choice. The output can be an action or an opinion of choice.- Overview :Human performance in decision terms...

in both the political and economic spheres of life. Karl Marx, as well as some other communist philosophers, deliberately never provided a detailed description as to how communism would function as a social system, nor the precise ways in which the working class could or should rise up, nor any other material specifics of exactly how to get to communism from capitalism. In the Communist Manifesto, Marx does lay out a 10-point plan advising the redistribution of land and production to begin the transition to communism, but he ensured that even this was very general and all-encompassing. It has always been presumed that Marx intended these theories to read this way specifically so that later theorists in specific situations could adapt communism to their own localities and conditions.

Theory

According to communist theory, the only way to abolish capitalist inequalities is to have the proletariat (working class), who collectively constitute the main producer of wealth in society, and who are perpetually exploitedExploitation

This article discusses the term exploitation in the meaning of using something in an unjust or cruel manner.- As unjust benefit :In political economy, economics, and sociology, exploitation involves a persistent social relationship in which certain persons are being mistreated or unfairly used for...

and marginalised by the bourgeoisie

Bourgeoisie

In sociology and political science, bourgeoisie describes a range of groups across history. In the Western world, between the late 18th century and the present day, the bourgeoisie is a social class "characterized by their ownership of capital and their related culture." A member of the...

(wealthy class), to overthrow the capitalist system in a wide-ranging social revolution

Social revolution

The term social revolution may have different connotations depending on the speaker.In the Trotskyist movement, the term "social revolution" refers to an upheaval in which existing property relations are smashed...

. The revolution, in the theory of most individuals and groups espousing communist revolution