Space Race

Encyclopedia

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

(USSR) and the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

(US) for supremacy in space exploration. Between 1957 and 1975, Cold War

Cold War

The Cold War was the continuing state from roughly 1946 to 1991 of political conflict, military tension, proxy wars, and economic competition between the Communist World—primarily the Soviet Union and its satellite states and allies—and the powers of the Western world, primarily the United States...

rivalry between the two nations focused on attaining firsts in space exploration, which were seen as necessary for national security and symbolic of technological and ideological superiority. The Space Race involved pioneering efforts to launch artificial satellites

Satellite

In the context of spaceflight, a satellite is an object which has been placed into orbit by human endeavour. Such objects are sometimes called artificial satellites to distinguish them from natural satellites such as the Moon....

, sub-orbital and orbital human spaceflight

Human spaceflight

Human spaceflight is spaceflight with humans on the spacecraft. When a spacecraft is manned, it can be piloted directly, as opposed to machine or robotic space probes and remotely-controlled satellites....

around the Earth, and piloted voyages to the Moon

Moon

The Moon is Earth's only known natural satellite,There are a number of near-Earth asteroids including 3753 Cruithne that are co-orbital with Earth: their orbits bring them close to Earth for periods of time but then alter in the long term . These are quasi-satellites and not true moons. For more...

. It effectively began with the Soviet launch of the Sputnik 1 artificial satellite on 4 October 1957, and concluded with the co-operative Apollo-Soyuz Test Project

Apollo-Soyuz Test Project

-Backup crew:-Crew notes:Jack Swigert had originally been assigned as the command module pilot for the ASTP prime crew, but prior to the official announcement he was removed as punishment for his involvement in the Apollo 15 postage stamp scandal.-Soyuz crew:...

human spaceflight mission in July 1975. The Apollo-Soyuz Test Project came to symbolize détente

Détente

Détente is the easing of strained relations, especially in a political situation. The term is often used in reference to the general easing of relations between the Soviet Union and the United States in the 1970s, a thawing at a period roughly in the middle of the Cold War...

, a partial easing of strained relations between the USSR and the US.

The Space Race had its origins in the missile-based arms race that occurred just after the end of the World War II, when both the Soviet Union and the United States captured advanced German rocket technology and personnel.

The Space Race sparked unprecedented increases in spending on education and pure research, which accelerated scientific advancements and led to beneficial spin-off technologies

Government spin-off

Government spin-off is civilian goods which are the result of military or governmental research. One prominent example of a type of government spin-off is technology that has been commercialized through NASA funding, research, licensing, facilities, or assistance. NASA spin-off technologies have...

. An unforeseen effect was that the Space Race contributed to the birth of the environmental movement

Environmental movement

The environmental movement, a term that includes the conservation and green politics, is a diverse scientific, social, and political movement for addressing environmental issues....

; the first color pictures of Earth taken from deep space were used as icons by the movement to show the planet as a fragile "blue marble" surrounded by the blackness of space.

Some famous probes and missions include Sputnik 1, Explorer 1, Vostok 1, Mariner 2, Ranger 7, Luna 9, Apollo 8, and Apollo 11.

World War II

The Space Race can trace its origins to Nazi GermanyNazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

, beginning in the 1930s and continuing during World War II when Germany researched and built operational ballistic missiles. Starting in the early 1930s, German

Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic is the name given by historians to the parliamentary republic established in 1919 in Germany to replace the imperial form of government...

aerospace engineers experimented with liquid-fueled rocket

Rocket

A rocket is a missile, spacecraft, aircraft or other vehicle which obtains thrust from a rocket engine. In all rockets, the exhaust is formed entirely from propellants carried within the rocket before use. Rocket engines work by action and reaction...

s, with the goal that one day they would be capable of reaching high altitudes and traversing long distances. The head of the German Army's Ballistics and Munitions Branch, Lieutenant Colonel Karl Emil Becker, gathered a small team of engineers that included Walter Dornberger

Walter Dornberger

Major-General Dr Walter Robert Dornberger was a German Army artillery officer whose career spanned World Wars I and II. He was a leader of Germany's V-2 rocket program and other projects at the Peenemünde Army Research Center....

and Leo Zanssen, to figure out how to use rockets as long-range artillery

Artillery

Originally applied to any group of infantry primarily armed with projectile weapons, artillery has over time become limited in meaning to refer only to those engines of war that operate by projection of munitions far beyond the range of effect of personal weapons...

in order to get around the Treaty of Versailles

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was one of the peace treaties at the end of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1919, exactly five years after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The other Central Powers on the German side of...

' ban on research and development of long-range cannon

Cannon

A cannon is any piece of artillery that uses gunpowder or other usually explosive-based propellents to launch a projectile. Cannon vary in caliber, range, mobility, rate of fire, angle of fire, and firepower; different forms of cannon combine and balance these attributes in varying degrees,...

s. Wernher von Braun

Wernher von Braun

Wernher Magnus Maximilian, Freiherr von Braun was a German rocket scientist, aerospace engineer, space architect, and one of the leading figures in the development of rocket technology in Nazi Germany during World War II and in the United States after that.A former member of the Nazi party,...

, a young engineering prodigy, was recruited by Becker and Dornberger to join their secret army program at Kummersdorf-West

Kummersdorf

Kummersdorf is the name of an estate near Luckenwalde at , around 25km south of Berlin, in the Brandenburg region of Germany. Until 1945 Kummersdorf hosted the weapon office of the German Army which ran a development centre for future weapons as well as an artillery range.In 1929 the Army Weapons...

in 1932. Von Braun had romantic dreams about conquering outer space with rockets, and did not initially see the military value in missile technology.

During the Second World War, General Dornberger was the military head of the army's rocket program, Zanssen became the commandant of the Peenemünde

Peenemünde

The Peenemünde Army Research Center was founded in 1937 as one of five military proving grounds under the Army Weapons Office ....

army rocket centre, and von Braun was the technical director of the ballistic missile

Ballistic missile

A ballistic missile is a missile that follows a sub-orbital ballistic flightpath with the objective of delivering one or more warheads to a predetermined target. The missile is only guided during the relatively brief initial powered phase of flight and its course is subsequently governed by the...

program. They would lead the team that built the Aggregate-4 (A-4) rocket, which became the first vehicle to reach outer space

Outer space

Outer space is the void that exists between celestial bodies, including the Earth. It is not completely empty, but consists of a hard vacuum containing a low density of particles: predominantly a plasma of hydrogen and helium, as well as electromagnetic radiation, magnetic fields, and neutrinos....

during its test flight program in 1942 and 1943. By 1943, Germany began mass producing the A-4 as the Vergeltungswaffe 2

V-2 rocket

The V-2 rocket , technical name Aggregat-4 , was a ballistic missile that was developed at the beginning of the Second World War in Germany, specifically targeted at London and later Antwerp. The liquid-propellant rocket was the world's first long-range combat-ballistic missile and first known...

(“Vengeance Weapon” 2, or more commonly, V2), a ballistic missile with a 320 kilometres (198.8 mi) range carrying a 1130 kilograms (2,491.2 lb) warhead

Warhead

The term warhead refers to the explosive material and detonator that is delivered by a missile, rocket, or torpedo.- Etymology :During the early development of naval torpedoes, they could be equipped with an inert payload that was intended for use during training, test firing and exercises. This...

at 4000 kilometre per hour. Its supersonic speed meant there was no defense against it, and radar

Radar

Radar is an object-detection system which uses radio waves to determine the range, altitude, direction, or speed of objects. It can be used to detect aircraft, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor vehicles, weather formations, and terrain. The radar dish or antenna transmits pulses of radio...

detection provided little warning. Germany used the weapon to bombard southern England and parts of Allied-liberated western Europe from 1944 until 1945. After the war, the V-2 became the basis of early American and Soviet rocket designs.

At war’s end, American, British, and Soviet scientific intelligence teams competed to capture Germany's rocket engineers

Aerospace engineering

Aerospace engineering is the primary branch of engineering concerned with the design, construction and science of aircraft and spacecraft. It is divided into two major and overlapping branches: aeronautical engineering and astronautical engineering...

along with the German rockets themselves and the designs they were based on. Each of the Allies captured a share of the available members of the German rocket team, but the United States benefited the most with Operation Paperclip

Operation Paperclip

Operation Paperclip was the Office of Strategic Services program used to recruit the scientists of Nazi Germany for employment by the United States in the aftermath of World War II...

, recruiting von Braun and most of his engineering team, who later helped develop the American missile and space exploration programs. The United States also acquired a large number of complete V2 rockets.

Rocket teams assembled

The German rocket center at Peenemünde was located in the eastern part of Germany, which became the Soviet zone of occupation. On Stalin's orders, the Soviet Union sent its best rocket engineers to this region to see what they could salvage for future weapons systems. The Soviet rocket engineers were led by Sergei Korolev. He had been involved in space clubs and early Soviet rocket design in the 1930s, but was arrested in 1938 during Joseph Stalin'sJoseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

Great Purge

Great Purge

The Great Purge was a series of campaigns of political repression and persecution in the Soviet Union orchestrated by Joseph Stalin from 1936 to 1938...

and imprisoned for six years in Siberia. After the war, he became the USSR's chief rocket and spacecraft engineer, essentially the Soviets' counterpart to Von Braun. His identity was kept a state secret throughout the Cold War, and he was identified publicly only as "the Chief Designer." In the West, his name was only officially revealed when he died in 1966.

After almost a year in the area around Peenemünde, Soviet officials moved most of the captured German rocket specialists to Gorodomlya Island

Gorodomlya Island

Gorodomlya Island is located on the Seliger Lake in the Tver Oblast of Russia. It is 200 miles northwest of Moscow.The Soviet government established a biological research center at Gorodomlya Island in 1928...

on Lake Seliger

Lake Seliger

Seliger is a lake in Tver Oblast and, in the extreme northern part, Novgorod Oblast of Russia, in the northwest of the Valdai Hills, a part of the Volga basin. Absolute height: 205 m, area 212 km², average depth 5.8 m....

, about 240 kilometres (149.1 mi) northwest of Moscow. They were not allowed to participate in Soviet missile design, but were used as problem-solving consultants to the Soviet engineers. They helped in the following areas: the creation of a Soviet version of the A-4; work on "organizational schemes"; research in improving the A-4 main engine; development of a 100-ton engine; assistance in the "layout" of plant production rooms; and preparation of rocket assembly using German components. With their help, particularly Helmut Groettrup's group, Korolev reverse-engineered

Reverse engineering

Reverse engineering is the process of discovering the technological principles of a device, object, or system through analysis of its structure, function, and operation...

the A-4 and built his own version of the rocket, the R-1

R-1 (missile)

The R-1 rocket was a copy of the German V-2 rocket manufactured by the Soviet Union. Even though it was a copy, it was manufactured using Soviet industrial plants and gave the Soviets valuable experience which later enabled the USSR to construct its own much more capable rockets.In 1945 the...

, in 1948. Later, he developed his own distinct designs, though many of these designs were influenced by the Groettrup Group's G4-R10 design from 1949. The Germans were eventually repatriated in 1951–53.

In America, Von Braun and his team were sent to the United States Army's White Sands Proving Ground

White Sands Missile Range

White Sands Missile Range is a rocket range of almost in parts of five counties in southern New Mexico. The largest military installation in the United States, WSMR includes the and the WSMR Otera Mesa bombing range...

, located in New Mexico

New Mexico

New Mexico is a state located in the southwest and western regions of the United States. New Mexico is also usually considered one of the Mountain States. With a population density of 16 per square mile, New Mexico is the sixth-most sparsely inhabited U.S...

, in 1945. They set about assembling the captured V2s and began a program of launching them and instructing American engineers in their operation. These tests led to the first rocket to take photos from outer space, and the first two-stage rocket, the WAC Corporal

Wac Corporal

The WAC or WAC Corporal was the first sounding rocket developed in the United States. Begun as a spinoff of the Corporal program, the WAC was a "little sister" to the larger Corporal. It was designed and built jointly by the Douglas Aircraft Company and the Guggenheim Aeronautical Laboratory.The...

-V2 combination, in 1949. The German rocket team was moved from Fort Bliss

Fort Bliss

Fort Bliss is a United States Army post in the U.S. states of New Mexico and Texas. With an area of about , it is the Army's second-largest installation behind the adjacent White Sands Missile Range. It is FORSCOM's largest installation, and has the Army's largest Maneuver Area behind the...

to the Army's new Redstone Arsenal

Redstone Arsenal

Redstone Arsenal is a United States Army base and a census-designated place adjacent to Huntsville in Madison County, Alabama, United States and is part of the Huntsville-Decatur Combined Statistical Area...

, located in Huntsville, Alabama

Huntsville, Alabama

Huntsville is a city located primarily in Madison County in the central part of the far northern region of the U.S. state of Alabama. Huntsville is the county seat of Madison County. The city extends west into neighboring Limestone County. Huntsville's population was 180,105 as of the 2010 Census....

, in 1950. From here, Von Braun and his team would develop the Army's first operational medium-range ballistic missile, the Redstone rocket, that would, in slightly modified versions, launch both America's first satellite, and the first piloted Mercury space missions. It became the basis for both the Jupiter

Jupiter-C

The Jupiter-C was an American sounding rocket used for three sub-orbital spaceflights in 1956 and 1957 to test re-entry nosecones that were later to be deployed on the more advanced PGM-19 Jupiter mobile missile....

and Saturn family of rockets

Saturn (rocket family)

The Saturn family of American rocket boosters was developed by a team of mostly German rocket scientists led by Wernher von Braun to launch heavy payloads to Earth orbit and beyond. Originally proposed as a military satellite launcher, they were adopted as the launch vehicles for the Apollo moon...

.

Cold War arms race

The Cold WarCold War

The Cold War was the continuing state from roughly 1946 to 1991 of political conflict, military tension, proxy wars, and economic competition between the Communist World—primarily the Soviet Union and its satellite states and allies—and the powers of the Western world, primarily the United States...

(1947–1991) developed between two former allies, the Soviet Union and the United States, soon after the end of the Second World War. It involved a continuing state of political conflict, military tension, proxy wars, and economic competition, primarily between the Soviet Union and its satellite states, and the powers of the Western world, particularly the United States. Although the primary participants' military forces never clashed directly, they expressed this conflict through military coalitions, strategic conventional force deployments, extensive aid to states deemed vulnerable, proxy wars, espionage, propaganda, a nuclear arms race, and economic and technological competitions, such as the Space Race.

In simple terms, the Cold War can be viewed as an expression of the ideological struggle between communism

Communism

Communism is a social, political and economic ideology that aims at the establishment of a classless, moneyless, revolutionary and stateless socialist society structured upon common ownership of the means of production...

and capitalism

Capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system that became dominant in the Western world following the demise of feudalism. There is no consensus on the precise definition nor on how the term should be used as a historical category...

. The United States faced a new uncertainty beginning in September 1949, when it lost its monopoly on the atomic bomb

Nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission or a combination of fission and fusion. Both reactions release vast quantities of energy from relatively small amounts of matter. The first fission bomb test released the same amount...

. American intelligence agencies discovered that the Soviet Union had exploded its first atomic bomb, with the consequence that the United States potentially could face a future nuclear war that, for the first time, might devastate its cities. Given this new danger, the United States participated in an arms race with the Soviet Union that included development of the hydrogen bomb, as well as intercontinental strategic bomber

Strategic bomber

A strategic bomber is a heavy bomber aircraft designed to drop large amounts of ordnance onto a distant target for the purposes of debilitating an enemy's capacity to wage war. Unlike tactical bombers, which are used in the battle zone to attack troops and military equipment, strategic bombers are...

s and intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) capable of delivering nuclear weapons. A new fear of communism and its sympathizers swept the United States during the 1950s, which devolved into paranoid McCarthyism

McCarthyism

McCarthyism is the practice of making accusations of disloyalty, subversion, or treason without proper regard for evidence. The term has its origins in the period in the United States known as the Second Red Scare, lasting roughly from the late 1940s to the late 1950s and characterized by...

. With communism spreading in China, Korea, and Eastern Europe, Americans came to feel so threatened that popular and political culture condoned extensive "witch-hunt

Witch-hunt

A witch-hunt is a search for witches or evidence of witchcraft, often involving moral panic, mass hysteria and lynching, but in historical instances also legally sanctioned and involving official witchcraft trials...

s" to expose communist spies. Part of the American reaction to the Soviet atomic and hydrogen bomb tests included maintaining a large Air Force

United States Air Force

The United States Air Force is the aerial warfare service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the American uniformed services. Initially part of the United States Army, the USAF was formed as a separate branch of the military on September 18, 1947 under the National Security Act of...

, under the control of the Strategic Air Command

Strategic Air Command

The Strategic Air Command was both a Major Command of the United States Air Force and a "specified command" of the United States Department of Defense. SAC was the operational establishment in charge of America's land-based strategic bomber aircraft and land-based intercontinental ballistic...

(SAC). SAC employed intercontinental strategic bombers, as well as medium-bombers based close to Soviet airspace (in western Europe and in Turkey

Turkey

Turkey , known officially as the Republic of Turkey , is a Eurasian country located in Western Asia and in East Thrace in Southeastern Europe...

) that were capable of delivering nuclear payloads.

For its part, the Soviet Union harbored fears of invasion. Having suffered at least 27 million casualties during World War II after being invaded by Nazi Germany in 1941, the Soviet Union was wary of its former ally, the United States, which until late 1949 was the sole possessor of atomic weapons. The United States had used these weapons operationally during World War II, and it could use them again against the Soviet Union, laying waste its cities and military centers. Since the Americans had a much larger air force than the Soviet Union, and the United States maintained advance air bases near Soviet territory, in 1947 Stalin ordered the development of intercontinental ballistic missile

Intercontinental ballistic missile

An intercontinental ballistic missile is a ballistic missile with a long range typically designed for nuclear weapons delivery...

s (ICBMs) in order to counter the perceived American threat.

In 1953, Korolev was given the go-ahead to develop the R-7 Semyorka

R-7 Semyorka

The R-7 was a Soviet missile developed during the Cold War, and the world's first intercontinental ballistic missile. The R-7 made 28 launches between 1957 and 1961, but was never deployed operationally. A derivative, the R-7A, was deployed from 1960 to 1968...

rocket, which represented a major advance from the German design. Although some of its components (notably boosters) still resembled the German G-4, the new rocket incorporated staged design, a completely new control system, and a new fuel. It was successfully tested on 21 August 1957 and became the world's first fully operational ICBM the following month. It would later be used to launch the first satellite into space, and derivatives would launch all piloted Soviet spacecraft.

The United States had multiple rocket programs divided among the different branches of the American armed services, which meant that each force developed its own ICBM program. The Air Force initiated ICBM research in 1945 with the MX-774. However, its funding was cancelled and only three partially successful launches were conducted in 1947. In 1951, the Air Force began a new ICBM program called MX-1593, and by 1955 this program was receiving top-priority funding. The MX-1593 program evolved to become the Atlas-A, with its maiden launch occurring on 11 June 1957, becoming the first successful American ICBM. Its upgraded version, the Atlas-D rocket, would later serve as an operational nuclear ICBM and be used as the orbital launch vehicle for Project Mercury

Project Mercury

In January 1960 NASA awarded Western Electric Company a contract for the Mercury tracking network. The value of the contract was over $33 million. Also in January, McDonnell delivered the first production-type Mercury spacecraft, less than a year after award of the formal contract. On February 12,...

and the remote-controlled Agena Target Vehicle

Agena Target Vehicle

The Agena Target Vehicle was an unmanned spacecraft used by NASA during its Gemini program to develop and practice orbital space rendezvous and docking techniques and to perform large orbital changes, in preparation for the Apollo program lunar missions.-Operations:Each ATV consisted of an Agena-D...

used in Project Gemini

Project Gemini

Project Gemini was the second human spaceflight program of NASA, the civilian space agency of the United States government. Project Gemini was conducted between projects Mercury and Apollo, with ten manned flights occurring in 1965 and 1966....

.

With the Cold War as an engine for change in the ideological competition between the United States and the Soviet Union, a coherent space policy began to take shape in the United States during the late 1950s. Korolev would take much inspiration from the competition as well, achieving many firsts to counter the possibility that the United States might prevail.

Beginnings

In 1955, with both the United States and the Soviet Union building ballistic missiles that could be utilized to launch objects into space, the "starting line" was drawn for the Space Race. In separate announcements, just four days apart, both nations publicly announced that they would launch artificial Earth satellites by 1957 or 1958. On 29 July 1955, James C. HagertyJames C. Hagerty

James Campbell Hagerty served as the only White House Press Secretary from 1953 to 1961 during the administration of Dwight D. Eisenhower.Hagerty attended Evander Childs High School in the Bronx, and was a graduate of Blair Academy, which he attended for his last two years in high school...

, president Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower was the 34th President of the United States, from 1953 until 1961. He was a five-star general in the United States Army...

's press secretary, announced that the United States intended to launch "small Earth circling satellites" between 1 July 1957 and 31 December 1958 as part of their contribution to the International Geophysical Year

International Geophysical Year

The International Geophysical Year was an international scientific project that lasted from July 1, 1957, to December 31, 1958. It marked the end of a long period during the Cold War when scientific interchange between East and West was seriously interrupted...

(IGY). Four days later, at the Sixth Congress of International Astronautical Federation

International Astronautical Federation

International Astronautical Federation , the world's foremost space advocacy organisation, is based in Paris. It was founded in 1951 as a non-governmental organization. It has 206 members from 58 countries across the world. They are drawn from space agencies, industry, professional associations,...

in Copenhagen

Copenhagen

Copenhagen is the capital and largest city of Denmark, with an urban population of 1,199,224 and a metropolitan population of 1,930,260 . With the completion of the transnational Øresund Bridge in 2000, Copenhagen has become the centre of the increasingly integrating Øresund Region...

, scientist Leonid I. Sedov

Leonid I. Sedov

Leonid Ivanovitch Sedov was a leading physicist of the Soviet Union.During WW2 he devised the so-called Sedov Similarity Solution for a blast wave. He was also the first chairman of the USSR Space Exploration program and broke first news of its existence in 1955...

spoke to international reporters at the Soviet embassy, and announced his country's intention to launch a satellite as well, in the "near future". On 30 August 1955, Korolev managed to get the Soviet Academy of Sciences to create a commission whose purpose was to beat the Americans into Earth orbit: this was the defacto start date for the Space Race.

Initially, President Eisenhower was worried that a satellite passing above a nation at over 100 kilometres (62.1 mi), might be construed as violating that nation's sovereign airspace. He was concerned that the Soviet Union would accuse the Americans of an illegal overflight, thereby scoring a propaganda victory at his expense. Eisenhower and his advisors believed that a nation's airspace sovereignty did not extend into outer space, acknowledged as the Kármán line

Karman line

The Kármán line lies at an altitude of above the Earth's sea level, and is commonly used to define the boundary between the Earth's atmosphere and outer space...

, and he used the 1957–58 International Geophysical Year launches to establish this principle in international law. Eisenhower also feared that he might cause an international incident and be called a "Warmonger

Warmonger

A warmonger is a pejorative term that is used to describe someone who is eager to encourage a people or nation to go to war.The term may also refer to:* Warmonger, a 2002 novel based on the Doctor Who television series...

" if he were to use military missiles as launchers. Therefore he selected the untried Naval Research Laboratory's Vanguard rocket

Vanguard rocket

The Vanguard rocket was intended to be the first launch vehicle the United States would use to place a satellite into orbit. Instead, the Sputnik crisis caused by the surprise launch of Sputnik 1 led the U.S., after the failure of Vanguard TV3, to quickly orbit the Explorer 1 satellite using a Juno...

, which was a research-only booster. This meant that von Braun's team was not allowed to put a satellite into orbit with their Jupiter-C rocket, because of its intended use as a future military vehicle. On 20 September 1956, von Braun and his team did launch a Jupiter-C that was capable of putting a satellite into orbit, however the launch was used only as a suborbital test of nose cone reentry technology. Had von Braun's team been allowed to orbit a satellite in 1956, the Space Race might have been over before it gained sufficient momentum to yield real benefits.

First artificial satellites

Korolev received word about von Braun's 1956 Jupiter-C test, but thinking it was a satellite mission that failed, he expedited plans to get his own satellite in orbit. Since his R-7 was substantially more powerful than any of the American boosters, he made sure to take full advantage of this capability by designing Object D

Sputnik 3

Sputnik 3 was a Soviet satellite launched on May 15, 1958 from Baikonur cosmodrome by a modified R-7/SS-6 ICBM. It was a research satellite to explore the upper atmosphere and the near space, and carried a large array of instruments for geophysical research....

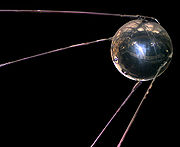

as his primary satellite. It was given the designation 'D', to distinguish it from other R-7 payload designations 'A', 'B', 'G', and 'V' which were nuclear weapon payloads. Object D would dwarf the proposed American satellites, by having a weight of 1400 kilograms (3,086.5 lb), of which 300 kilograms (661.4 lb) would be composed of scientific instruments that would photograph the Earth, take readings on radiation levels, and check on the planet's magnetic field. However, things were not going along well with the design and manufacturing of the satellite, so in February 1957, Korolev sought and received permission from the USSR Council of Ministers to create a prosteishy sputnik (PS-1), or simple satellite. The Council also decreed that Object D be postponed until April 1958. The new sputnik was a shiny spherical ball that would be a much lighter craft, weighing 83.8 kilograms (184.7 lb) and having a 58 centimetres (22.8 in) diameter.

The satellite would not contain the complex instrumentation that Object D had, but it did have two radio transmitters operating on different short wave radio frequencies, the ability to detect if a meteoroid were to penetrate its pressure hull, and the ability to detect the density of the Earth's thermosphere

Thermosphere

The thermosphere is the biggest of all the layers of the Earth's atmosphere directly above the mesosphere and directly below the exosphere. Within this layer, ultraviolet radiation causes ionization. The International Space Station has a stable orbit within the middle of the thermosphere, between...

.

Korolev was buoyed by the first successful launches of his R-7 rocket in August and September, paving the way for him to launch his sputnik. Word came that the Americans were planning to announce a major breakthrough at an International Geophysical Year conference at the National Academy of Sciences

United States National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences is a corporation in the United States whose members serve pro bono as "advisers to the nation on science, engineering, and medicine." As a national academy, new members of the organization are elected annually by current members, based on their distinguished and...

in Washington D.C., with a paper entitled "Satellite Over the Planet", on 6 October 1957. Korolev's fear was that von Braun might launch a Jupiter-C with a satellite payload, on, or around, the fourth or fifth of October, in conjunction with the paper. The fear of being beaten made him hasten the launch, moving it to the fourth of October. The launch vehicle for PS-1, was a modified R-7 – vehicle 8K71PS number M1-PS– without much of the test equipment and radio gear that was present in the previous launches. It arrived at the Soviet missile base Tyura-Tam

Baikonur Cosmodrome

The Baikonur Cosmodrome , also called Tyuratam, is the world's first and largest operational space launch facility. It is located in the desert steppe of Kazakhstan, about east of the Aral Sea, north of the Syr Darya river, near Tyuratam railway station, at 90 meters above sea level...

in September and was prepared for its mission at launch site number one

Gagarin's Start

Gagarin's Start is a launch site at Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan, used for the Soviet space program and now managed by the Russian Federal Space Agency....

. On Friday, 4 October 1957, at exactly 10:28:34 p.m. Moscow time, the R-7, with the now named Sputnik 1

Sputnik 1

Sputnik 1 ) was the first artificial satellite to be put into Earth's orbit. It was launched into an elliptical low Earth orbit by the Soviet Union on 4 October 1957. The unanticipated announcement of Sputnik 1s success precipitated the Sputnik crisis in the United States and ignited the Space...

satellite, lifted off the launch pad, and placed this artificial "moon" into an orbit a few minutes later. But the celebrations were muted at the launch control centre until the down-range far east tracking station at Kamchatka

Yelizovo

Yelizovo is a town in Kamchatka Krai, Russia, located on the Avacha River northwest of Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky. Population: Founded in 1848 as the village of Stary Ostrog , it was renamed Zavoyko in 1897, after the Russian admiral Vasily Zavoyko who led the defense of Petropavlovsk in 1854....

received the first distinctive beep...beep...beep sounds from Sputnik 1's radio transmitters, indicating that it was on its way to completing its first orbit. About 95 minutes after launch, the satellite flew over its launch site, and its radio signals were picked up by the engineers and military personnel at Tyura-Tam: that's when Korolev and his team celebrated the first successful artificial satellite placed into Earth-orbit.

Vanguard TV3

Vanguard TV3 was the first attempt of the United States to launch a satellite into orbit around the Earth. It was a small satellite designed to test the launch capabilities of the three-stage Vanguard rocket and study the effects of the environment on a satellite and its systems in Earth orbit...

occurred at Cape Canaveral

Cape Canaveral

Cape Canaveral, from the Spanish Cabo Cañaveral, is a headland in Brevard County, Florida, United States, near the center of the state's Atlantic coast. Known as Cape Kennedy from 1963 to 1973, it lies east of Merritt Island, separated from it by the Banana River.It is part of a region known as the...

in front of a live broadcast television audience in the United States. Only in the wake of this very public failure did von Braun's Redstone team get the go-ahead to launch their Jupiter-C rocket as soon as they could. Nearly four months after the launch of Sputnik 1, von Braun and the United States successfully launched its first satellite, on a modified Redstone booster, under the "civilian" name Juno 1 to differentiate it from the army's Redstone missile. The Juno 1 carried the Explorer 1 satellite, and the Explorer 1's flight data confirmed the existence of an Earth-encompassing radiation belt

Van Allen radiation belt

The Van Allen radiation belt is a torus of energetic charged particles around Earth, which is held in place by Earth's magnetic field. It is believed that most of the particles that form the belts come from solar wind, and other particles by cosmic rays. It is named after its discoverer, James...

, previously theorized by James Van Allen

James Van Allen

James Alfred Van Allen was an American space scientist at the University of Iowa.The Van Allen radiation belts were named after him, following the 1958 satellite missions in which Van Allen had argued that a Geiger counter should be used to detect charged particles.- Life and career :* September...

. Confirmation of the Van Allen radiation belt was considered one of the outstanding discoveries of the International Geophysical Year.

First humans in space

On 12 April 1961, the Soviet Union won the race with the United States to get a human into space, when Yuri GagarinYuri Gagarin

Yuri Alekseyevich Gagarin was a Soviet pilot and cosmonaut. He was the first human to journey into outer space, when his Vostok spacecraft completed an orbit of the Earth on April 12, 1961....

was launched into orbit around the Earth on Vostok 1

Vostok 1

Vostok 1 was the first spaceflight in the Vostok program and the first human spaceflight in history. The Vostok 3KA spacecraft was launched on April 12, 1961. The flight took Yuri Gagarin, a cosmonaut from the Soviet Union, into space. The flight marked the first time that a human entered outer...

. They dubbed Gagarin the first cosmonaut, roughly translated from Russian and Greek as "sailor of the universe". Although he had the ability to take over manual control of his spacecraft in an emergency, it was flown in an automatic mode as a precaution; medical science at that time did not know what would happen to a human in the weightlessness of space. Vostok 1 orbited the Earth for 108 minutes and made its reentry over the Soviet Union, with Gagarin ejecting from the spacecraft at 7000 metres (22,965.9 ft), and landing by parachute. Under Fédération Aéronautique Internationale

Fédération Aéronautique Internationale

The Fédération Aéronautique Internationale is the world governing body for air sports and aeronautics and astronautics world records. Its head office is in Lausanne, Switzerland. This includes man-carrying aerospace vehicles from balloons to spacecraft, and unmanned aerial vehicles...

(International Federation of Aeronautics) FAI qualifying rules for aeronautical records, pilots must both take off and land with their craft, so the Soviets kept the landing procedures secret until 1978, when they finally admitted that Gagarin did not land with his spacecraft. When the flight was publicly announced, it was celebrated around the world as a great triumph, not just for the Soviet Union, but for the world itself, though it once again shocked and embarrassed the United States.

The United States called their space travelers astronaut

Astronaut

An astronaut or cosmonaut is a person trained by a human spaceflight program to command, pilot, or serve as a crew member of a spacecraft....

s ("star sailors" from the Greek), and it was 3 weeks later, on 5 May 1961, when Alan Shepard

Alan Shepard

Alan Bartlett Shepard, Jr. was an American naval aviator, test pilot, flag officer, and NASA astronaut who in 1961 became the second person, and the first American, in space. This Mercury flight was designed to enter space, but not to achieve orbit...

became the first one in space, launched on a suborbital mission Mercury-Redstone 3

Mercury-Redstone 3

Mercury-Redstone 3 was the first manned space mission of the United States. Astronaut Alan Shepard piloted a 15-minute Project Mercury suborbital flight in the Freedom 7 spacecraft on May 5, 1961 to become the first American in space, three weeks after the Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin had carried...

, in a spacecraft named Freedom 7. Though he did not achieve orbit, unlike Gagarin he was the first person to exercise manual control over his spacecraft's attitude and retro-rocket firing. The first Soviet cosmonaut to exercise manual control was Gherman Titov

Gherman Titov

Gherman Stepanovich Titov was a Soviet cosmonaut who, on August 6, 1961, became the second human to orbit the Earth aboard Vostok 2, preceded by Yuri Gagarin on Vostok 1...

in Vostok 2

Vostok 2

Vostok 2 was a Soviet space mission which carried cosmonaut Gherman Titov into orbit for a full day in order to study the effects of a more prolonged period of weightlessness on the human body...

on 6 August 1961.

Almost a year after the Soviets put a human into orbit, astronaut John Glenn

John Glenn

John Herschel Glenn, Jr. is a former United States Marine Corps pilot, astronaut, and United States senator who was the first American to orbit the Earth and the third American in space. Glenn was a Marine Corps fighter pilot before joining NASA's Mercury program as a member of NASA's original...

became the first American to orbit the Earth, on 20 February 1962. His Mercury-Atlas 6

Mercury-Atlas 6

Mercury-Atlas 6 was a human spaceflight mission conducted by NASA, the space agency of the United States. As part of Project Mercury, MA-6 was the successful first attempt by NASA to place an astronaut into orbit. The MA-6 mission was launched February 20, 1962. It made three orbits of the Earth,...

mission completed three orbits in the Friendship 7 spacecraft, and splashed-down safely in the Atlantic Ocean, after a tense reentry, due to what falsely appeared from the telemetry data to be a loose heat-shield.

Kennedy launches the Moon race

On 20 April 1961, about one week after Gagarin's flight, American President John F. Kennedy sent a memo to Vice President Lyndon B. JohnsonLyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson , often referred to as LBJ, was the 36th President of the United States after his service as the 37th Vice President of the United States...

, asking him to look into the state of America's space program, and into programs that could offer NASA the opportunity to catch up. Johnson responded about one week later, concluding that the United States needed to do much more to reach a position of leadership. Johnson recommended that a piloted moon landing was far enough in the future that it was likely that the United States could achieve it first.

On 25 May, Kennedy announced his support for the Apollo program and redefined the ultimate goal of the Space Race in an address to a special joint session of Congress:"I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth."

His justification for the Moon Race, was that it was both vital to national security and it would focus the nation's energies in other scientific and social fields. He expressed his reasoning in the famous "We choose the Moon speech," on 12 September 1962, before a large crowd at Rice University

Rice University

William Marsh Rice University, commonly referred to as Rice University or Rice, is a private research university located on a heavily wooded campus in Houston, Texas, United States...

Stadium, in Houston, Texas, near the site of the future Johnson Space Center

Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center

The Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center is the National Aeronautics and Space Administration's center for human spaceflight training, research and flight control. The center consists of a complex of 100 buildings constructed on 1,620 acres in Houston, Texas, USA...

.

Proposed Joint U.S.-U.S.S.R. Moon Program

On 20 September 1963, in a speech before the United Nations General Assembly, President Kennedy proposed that the United States and the Soviet Union join forces in their efforts to reach the moon. Soviet Premier Nikita KhrushchevNikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev led the Soviet Union during part of the Cold War. He served as First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964, and as Chairman of the Council of Ministers, or Premier, from 1958 to 1964...

initially rejected Kennedy's proposal, however during the next few weeks he concluded that both nations might realize cost benefits and technological gains from a joint venture. Khrushchev was poised to accept Kennedy's proposal at the time of Kennedy's assassination in November 1963.

Khrushchev and Kennedy had developed a measure of rapport during their years as leaders of the world's two superpowers, especially during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis

Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis was a confrontation among the Soviet Union, Cuba and the United States in October 1962, during the Cold War...

. That trust was lacking with Vice President Johnson; when Johnson assumed the Presidency after Kennedy's assassination, Khrushchev dropped the idea of a joint U.S.-U.S.S.R. moon program.

Vostoks and Voskhods

Vostok 3

Vostok 3 was a spaceflight of the Soviet space program intended to determine the ability of the human body to function in conditions of weightlessness and test the endurance of the Vostok 3KA spacecraft over longer flights...

and Vostok 4

Vostok 4

Vostok 4 was a mission in the Soviet space program. It was launched a day after Vostok 3 with cosmonaut Pavel Popovich on board—the first time that more than one manned spacecraft were in orbit at the same time. The two Vostok capsules came within of one another and ship-to-ship radio contact was...

on 11–15 August 1962. The two spacecraft came within approximately 6.5 kilometres (4 mi) of one another, close enough for radio communication. The launching of two spacecraft from the same pad during a very short period of time represented a significant technical accomplishment, however there was no capability for the spacecraft to maneuver closer to each other, and over the course of the mission they continued to drift as far as 2850 kilometres (1,770.9 mi) apart.

The Soviet Union achieved yet another first when it launched not only the first woman, but also the first civilian, in space-- Valentina Tereshkova

Valentina Tereshkova

Valentina Vladimirovna Tereshkova is a retired Soviet cosmonaut, and was the first woman in space. She was selected out of more than four hundred applicants, and then out of five finalists, to pilot Vostok 6 on the 16 June, 1963, becoming both the first woman and the first civilian to fly in...

, on 16 June 1963, in Vostok 6

Vostok 6

-Backup crew:-Reserve crew:Vostok VI-Mission parameters:*Mass: *Apogee: *Perigee: *Inclination: 64.9°*Period: 87.8 minutes9090...

. Launching a woman was reportedly Korolev's idea, and it was accomplished purely for propaganda value. Tereshkova was one of a small corps of female cosmonauts who were amateur parachutists, but Tereshkova was the only one to fly. The USSR didn't again open its cosmonaut corps to women until 1980, two years after the United States opened its astronaut corps to women.

Korolev had planned further, long-term missions for the Vostok spacecraft, and had four Vostoks in various stages of fabrication in late 1963 at his OKB-1

S.P. Korolev Rocket and Space Corporation Energia

OAO S.P. Korolev Rocket and Space Corporation Energia , also known as RKK Energiya, is a Russian manufacturer of spacecraft and space station components...

facilities. At that time, the Americans announced their ambitious plans for the Project Gemini flight schedule. These plans included major advancements in spacecraft capabilities, including a two-person spacecraft, the ability to change orbits, the capacity to perform an extravehicular activity (EVA), and the goal of docking with another spacecraft. These represented major advances over the previous Mercury or Vostok spaceships, and Korolev felt the need to try to beat the Americans to many of these innovations. Korolev already had begun designing the Vostok's replacement, the next-generation Soyuz spacecraft, a multi-cosmonaut spacecraft that had at least the same capabilities as the Gemini spacecraft. However, Soyuz would not be available for at least three years, and it could not be called upon to deal with this new American challenge in 1964 or 1965. Political pressure in early 1964–which some sources claim was from Khrushchev while other sources claim was from other Communist Party officials—pushed him to modify his four remaining Vostoks to beat the Americans to new space firsts in the size of flight crews, and the duration of missions.

On 12 October 1964, the Chief Designer delivered another Soviet space-first when Voskhod 1

Voskhod 1

Voskhod 1 was the seventh manned Soviet space flight. It achieved a number of "firsts" in the history of manned spaceflight, being the first space flight to carry more than one crewman into orbit, the first flight without the use of spacesuits, and the first to carry either an engineer or a...

launched the first multi-person spacecraft, with three cosmonauts in a modified Vostok spacecraft. The USSR touted another technological achievement during this mission: it was the first space flight during which cosmonauts performed in a shirt-sleeve-environment. However, flying without spacesuits was not due to safety improvements in the Soviet spacecraft's environmental systems; rather this innovation was accomplished because the craft's limited cabin space did not allow for spacesuits. Flying without spacesuits exposed the cosmonauts to significant risk in the event of potentially fatal cabin depressurization. This feat would not be repeated until the US Apollo Command Module flew in 1968; this later mission was designed from the outset to safely transport three astronauts in a shirt-sleeve environment

Shirt-sleeve environment

Shirt-sleeve environment is a term used in aircraft design to describe the interior of an aircraft in which no special clothing need be worn. Early aircraft had no internal pressurization, so the crews of those that reached the stratosphere had to be garbed to withstand the low temperature and...

while in space.

Between 14–16 October 1964, Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev – 10 November 1982) was the General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union , presiding over the country from 1964 until his death in 1982. His eighteen-year term as General Secretary was second only to that of Joseph Stalin in...

and a small cadre of high-ranking Communist Party officials, deposed Premier Khrushchev as Soviet government leader a day after Voskhod 1 landed, in what was called the "Wednesday conspiracy".

The new political leaders, along with Korolev, ended the technologically troublesome Voskhod program, cancelling Voskhod 3 and 4, which were in the planning stages, and started concentrating on the race to the moon. Voskhod 2 would end up being Korolev's final achievement before his death, as it would become the last of the many space firsts that demonstrated the USSR's domination in spacecraft technology during the early 1960s. According to historian Asif Siddiqi, Korolev's accomplishments marked "the absolute zenith of the Soviet space program, one never, ever attained since." There would be a two-year pause in Soviet piloted space flights while Voskhod's replacement, the Soyuz spacecraft, was designed and developed.

On 18 March 1965, about a week before the first American piloted Project Gemini space flight, the USSR accelerated the Space Race competition, by launching the two-cosmonaut Voskhod 2

Voskhod 2

Voskhod 2 was a Soviet manned space mission in March 1965. Vostok-based Voskhod 3KD spacecraft with two crew members on board, Pavel Belyaev and Alexei Leonov, was equipped with an inflatable airlock...

mission with Pavel Belyayev

Pavel Belyayev

Pavel Ivanovich Belyayev , , was a Soviet fighter pilot with extensive experience in piloting different types of aircraft...

and Alexey Leonov. Voskhod 2's design modifications included the first airlock to allow for extravehicular activity (EVA), also known as a spacewalk. Leonov performed the first-ever EVA as part of the mission. A fatality was narrowly avoided when Leonov's spacesuit expanded in the vacuum of space, preventing him from re-entering the spacecraft. He had to improvise, and perform the potentially fatal partial depressurization of his spacesuit in order to re-enter the airlock. He succeeded in safely re-entering the ship, but he and Belyayev faced further challenges when the spacecraft's atmospheric controls flooded the cabin with 45% pure oxygen, which had to be lowered to acceptable levels before re-entry. The reentry involved two more challenges: an improperly timed retrorocket firing caused the Voskhod 2 to land 386 kilometres (239.8 mi) off its designated target area, the town of Perm

Perm

Perm is a city and the administrative center of Perm Krai, Russia, located on the banks of the Kama River, in the European part of Russia near the Ural Mountains. From 1940 to 1957 it was named Molotov ....

; and the instrument compartment's failure to detach from the descent apparatus caused the spacecraft to become unstable during reentry.

Project Gemini

Focused by the commitment to a moon landing, in January 1962 the US introduced Project GeminiProject Gemini

Project Gemini was the second human spaceflight program of NASA, the civilian space agency of the United States government. Project Gemini was conducted between projects Mercury and Apollo, with ten manned flights occurring in 1965 and 1966....

, a two-crew-member spacecraft that would support Apollo by developing the key spaceflight technologies of space rendezvous

Space rendezvous

A space rendezvous is an orbital maneuver during which two spacecraft, one of which is often a space station, arrive at the same orbit and approach to a very close distance . Rendezvous requires a precise match of the orbital velocities of the two spacecraft, allowing them to remain at a constant...

and docking of two craft, flight durations of sufficient length to simulate going to the Moon and back, Extra-vehicular Activity for extended periods, and accomplishing useful work rather than just "walking in space." Although Gemini took a year longer than planned to accomplish its first flight, Gemini took advantage of the USSR's two-year hiatus after Voskhod, which enabled the US to catch up and surpass the previous Soviet lead in piloted spaceflight. Gemini achieved several significant firsts during the course of ten piloted missions:

- On Gemini 3Gemini 3Gemini 3 was the first manned mission in NASA's Gemini program, the second American manned space program. On March 23, 1965, the spacecraft, nicknamed The Molly Brown, performed the seventh manned US spaceflight, and the 17th manned spaceflight overall...

(March 1965), astronauts Virgil "Gus" Grissom and John W. Young became the first to demonstrate their ability to change their craft's orbit. - On Gemini 5Gemini 5Gemini 5 was a 1965 manned spaceflight in NASA's Gemini program. It was the third manned Gemini flight, the 11th manned American flight and the 19th spaceflight of all time...

(August 1965), astronauts L. Gordon CooperGordon CooperLeroy Gordon Cooper, Jr. , also known as Gordon Cooper, was an American aeronautical engineer, test pilot and NASA astronaut. Cooper was one of the seven original astronauts in Project Mercury, the first manned space effort by the United States...

and Charles "Pete" ConradPete ConradCharles "Pete" Conrad, Jr. was an American naval officer, astronaut and engineer, and the third person to walk on the Moon during the Apollo 12 mission. He set an eight-day space endurance record along with command pilot Gordon Cooper on the Gemini 5 mission, and commanded the Gemini 11 mission...

set a record of almost eight days in space, long enough for a piloted lunar mission. - On Gemini 6AGemini 6A-Backup crew:-Mission parameters:* Mass: * Perigee: * Apogee: * Inclination: 28.97°* Period: 88.7 min-Stationkeeping with GT-7:* Start: December 15, 1965 19:33 UTC* End: December 16, 1965 00:52 UTC-Objectives:...

(December 1965), Command Pilot Wally SchirraWally SchirraWalter Marty Schirra, Jr. was an American test pilot, United States Navy officer, and one of the original Mercury 7 astronauts chosen for the Project Mercury, America's effort to put humans in space. He is the only person to fly in all of America's first three space programs...

achieved the first space rendezvousSpace rendezvousA space rendezvous is an orbital maneuver during which two spacecraft, one of which is often a space station, arrive at the same orbit and approach to a very close distance . Rendezvous requires a precise match of the orbital velocities of the two spacecraft, allowing them to remain at a constant...

with Gemini 7Gemini 7Gemini 7 was a 1965 manned spaceflight in NASA's Gemini program. It was the 4th manned Gemini flight, the 12th manned American flight and the 20th spaceflight of all time . The crew of Frank F. Borman, II and James A...

, accurately matching his orbit to that of the other craft, station-keeping at distances as close as1 foot (0.3048 m), and keeping station for three consecutive orbits. - Gemini 7 also set a human spaceflight endurance record of fourteen days for Frank BormanFrank BormanFrank Frederick Borman, II is a retired NASA astronaut and engineer, best remembered as the Commander of Apollo 8, the first mission to fly around the Moon, making him, along with fellow crew mates Jim Lovell and Bill Anders, the first of only 24 humans to do so...

and James A. LovellJim LovellJames "Jim" Arthur Lovell, Jr., is a former NASA astronaut and a retired captain in the United States Navy, most famous as the commander of the Apollo 13 mission, which suffered a critical failure en route to the Moon but was brought back safely to Earth by the efforts of the crew and mission...

, which stood until both nations started launching space laboratories in the early 1970s. - On Gemini 8Gemini 8-Backup crew:-Mission parameters:* Mass: * Perigee: * Apogee: * Inclination: 28.91°* Period: 88.83 min-Objectives:Gemini VIII had two major objectives, of which it achieved one...

(March 1966), Command Pilot Neil ArmstrongNeil ArmstrongNeil Alden Armstrong is an American former astronaut, test pilot, aerospace engineer, university professor, United States Naval Aviator, and the first person to set foot upon the Moon....

achieved the first docking between two spacecraft, his Gemini craft and an Agena target vehicleAgena Target VehicleThe Agena Target Vehicle was an unmanned spacecraft used by NASA during its Gemini program to develop and practice orbital space rendezvous and docking techniques and to perform large orbital changes, in preparation for the Apollo program lunar missions.-Operations:Each ATV consisted of an Agena-D...

. - Gemini 11Gemini 11Gemini 11 was the ninth manned spaceflight mission of NASA's Project Gemini, which flew from September 12 to 15, 1966. It was the 17th manned American flight and the 25th spaceflight to that time . Astronauts Charles "Pete" Conrad, Jr. and Richard F. Gordon, Jr...

(September 1966), commanded by Conrad, achieved the first direct-ascent rendezvous with its Agena target on the first orbit, and used the Agena's rocket to achieve an apogee of 742 nautical miles (1,374.2 km), an earth orbit record never broken as of . - On Gemini 12Gemini 12-Backup crew:-Mission parameters:*Mass: *Perigee: *Apogee: *Inclination: 28.87°*Period: 88.87 min-Docking:*Docked: November 12, 1966 - 01:06:00 UTC*Undocked: November 13, 1966 - 20:18:00 UTC-Space walk:...

(November 1966), Edwin E. "Buzz" Aldrin spent over five hours working comfortably during three (EVA) sessions, finally proving that humans could perform productive tasks outside their spacecraft. (This proved to be the most difficult goal to achieve.)

Most of the novice pilots on the early missions would command the later missions. In this way, Project Gemini built up spaceflight experience for the pool of astronauts who would be chosen to fly the Apollo lunar missions.

Soviet Moon program

The circumlunar missions were to be launched by a UR-500 rocket, later known as the Proton. The cosmonauts would be flown to the Moon in the Soyuz 7K-L1

Soyuz 7K-L1

The Soyuz 7K-L1 spacecraft was designed to launch men from the Earth to circle the Moon without going into lunar orbit in the context of the Soviet manned moon-flyby program in Moon race. It was based on the Soyuz 7K-OK with several components stripped out to reduce the vehicle weight...

(Zond), which made four unsuccessful unmanned flights from 1967–1970. One flight of the Zond was, however, successful and returned its non-human passengers (tortoises) to earth; had it been used for a manned circumlunar mission, the flight would have carried two cosmonauts.

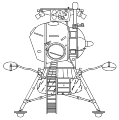

The Soviet lunar landing missions would use spacecraft derived from the Soyuz 7K-L1. The orbital module (Soyuz 7K-L3), the "Lunniy Orbitalny Korabl" (LOK), had a crew of two. The LOK and a separate lunar lander, the "Lunniy Korabl

LK Lander

The LK was a Soviet lunar lander and counterpart of the American Lunar Module . The LK was to have landed up to two cosmonauts on the Moon...

" (LK), had 40% of the mass of the Apollo CSM/LM due to the launch vehicle's capabilities.

The launch vehicle would have been the N1 rocket, which was roughly the same height and takeoff mass as the American Saturn V

Saturn V

The Saturn V was an American human-rated expendable rocket used by NASA's Apollo and Skylab programs from 1967 until 1973. A multistage liquid-fueled launch vehicle, NASA launched 13 Saturn Vs from the Kennedy Space Center, Florida with no loss of crew or payload...

, exceeded its takeoff thrust by 28%, yet had roughly half the TLI

Trans Lunar Injection

A Trans Lunar Injection is a propulsive maneuver used to set a spacecraft on a trajectory which will arrive at the Moon.Typical lunar transfer trajectories approximate Hohmann transfers, although low energy transfers have also been used in some cases, as with the Hiten probe...

payload capability. The N1 was unsuccessfully tested four times, exploding each time due to problems with the first stage's thirty engines.

The Soviet leadership cancelled the program in 1970 after the first two successful American Moon landings.

Fatalities and disasters of the 1960s

Likely the worst disaster during the Space Race was the Soviet Union's Nedelin catastropheNedelin catastrophe

The Nedelin catastrophe or Nedelin disaster was a launch pad accident that occurred on 24 October 1960, at Baikonur Cosmodrome during the development of the Soviet R-16 ICBM...

in 1960. It happened on 24 October 1960, when Chief Marshal Mitrofan Nedelin

Mitrofan Ivanovich Nedelin

Mitrofan Ivanovich Nedelin was a Soviet military commander who served as Chief Marshal of Artillery, a position he held from May 8, 1959 until his untimely death...

gave orders to use improper shutdown and control procedures on an experimental R-16 rocket. The hasty on-pad repairs caused the missile's second stage engine to fire straight onto the full propellant tanks of the still-attached first stage. The resulting explosion, toxic-fuel spill and fire, killed anywhere from 92 to 150 top Soviet military and technical personnel. Marshal Nedelin was vaporized, and his only identifiable remains were his war medals, especially the Gold Star of the Soviet Union

Hero of the Soviet Union

The title Hero of the Soviet Union was the highest distinction in the Soviet Union, awarded personally or collectively for heroic feats in service to the Soviet state and society.-Overview:...

. His death was officially explained as an airplane crash. It was also a huge set-back for the rocket's chief designer, Mikhail Yangel

Mikhail Yangel

Mikhail Kuzmich Yangel , was a leading missile designer in the Soviet Union....

, who was trying to unseat Korolev as the person responsible for the Soviet human spaceflight program. Yangel survived only because he went for a cigarette break in a bunker that was removed from the launch pad, but he would not rival Korolev during the rest of this period. The Nedelin catastrophe would remain an official secret until 1989, and the survivors of the incident were not allowed to discuss it until 1990, thirty-one years after it occurred.

In 1986, in a series of newspaper articles in Izvestia

Izvestia

Izvestia is a long-running high-circulation daily newspaper in Russia. The word "izvestiya" in Russian means "delivered messages", derived from the verb izveshchat . In the context of newspapers it is usually translated as "news" or "reports".-Origin:The newspaper began as the News of the...

, it was disclosed for the first time that the USSR had officially covered up the 23 March 1961 death of Soviet cosmonaut Valentin Bondarenko

Valentin Bondarenko

Valentin Vasiliyevich Bondarenko was a Soviet fighter pilot and cosmonaut. He died during a training accident in Moscow, USSR, in 1961. A crater on the Moon's far side is named for him.-Education and military training:...

from massive third-degree burns from a fire in a high-oxygen isolation test chamber. This revelation subsequently caused some speculation as to whether the Apollo 1

Apollo 1

Apollo 1 was scheduled to be the first manned mission of the Apollo manned lunar landing program, with a target launch date of February 21, 1967. A cabin fire during a launch pad test on January 27 at Launch Pad 34 at Cape Canaveral killed all three crew members: Command Pilot Virgil "Gus"...

disaster might have been averted had NASA been aware of the incident. Bondarenko, at age 24, was the youngest of the early Vostok cosmonauts. The Soviet government literally erased all traces of Bondarenko's existence in the cosmonaut corps upon his death.

In 1967, both nations faced serious challenges that brought their programs to a halt. Both nations had been rushing at full-speed on the Apollo and Soyuz programs, without paying due diligence to growing design and manufacturing problems. The results proved fatal to both pioneering crews.

In the United States, the first Apollo mission crew, Command Pilot "Gus" Grissom

Gus Grissom

Virgil Ivan Grissom , , better known as Gus Grissom, was one of the original NASA Project Mercury astronauts and a United States Air Force pilot...

, Senior Pilot Ed White

Edward Higgins White

Edward Higgins White, II was an engineer, United States Air Force officer and NASA astronaut. On June 3, 1965, he became the first American to "walk" in space. White died along with fellow astronauts Gus Grissom and Roger Chaffee during a pre-launch test for the first manned Apollo mission at...

, and Pilot Roger Chaffee, were killed by suffocation in a cabin fire that swept through their Apollo 1

Apollo 1

Apollo 1 was scheduled to be the first manned mission of the Apollo manned lunar landing program, with a target launch date of February 21, 1967. A cabin fire during a launch pad test on January 27 at Launch Pad 34 at Cape Canaveral killed all three crew members: Command Pilot Virgil "Gus"...

spacecraft during a ground test on 27 January 1967. The fire was probably caused by an electrical spark, and it grew out-of-control, fed by the spacecraft's pure oxygen atmosphere maintained at greater-than-normal atmospheric pressure. An investigative board detailed design and construction flaws in the spacecraft, and procedural failings including failure to appreciate the hazard of the pure-oxygen atmosphere as well as inadequate safety procedures. All these flaws had to be corrected over the next twenty-two months until the first piloted flight could be made.

Mercury and Gemini veteran Gus Grissom had been a favored choice of Deke Slayton

Deke Slayton

Donald Kent Slayton , better known as Deke Slayton, was an American World War II pilot and later, one of the original NASA Mercury Seven astronauts....

, the grounded Mercury astronaut who became NASA's Director of Flight Crew Operations, to make the first piloted landing.

Meanwhile, the Soviet Union was having its own problems with Soyuz development. Engineers reported 200 design faults to party leaders, but their concerns "were overruled by political pressures for a series of space feats to mark the anniversary of Lenin's birthday."

On April 24, 1967, the USSR suffered the death of its first cosmonaut, Colonel Vladimir Komarov, the single pilot of Soyuz 1

Soyuz 1

Soyuz 1 was a manned spaceflight of the Soviet space program. Launched into orbit on April 23, 1967 carrying cosmonaut Colonel Vladimir Komarov, Soyuz 1 was the first flight of the Soyuz spacecraft...

. This was planned to be a three-day mission to include the first Soviet docking with an unpiloted Soyuz 2

Soyuz 2

Soyuz 2 was an unpiloted spacecraft in the Soyuz family intended to perform a docking maneuver with Soyuz 3. Although the two craft approached closely, the docking did not take place.-Other uses of name:...

, but his mission was plagued with problems. Early on his craft lacked sufficient electrical power because only one of two solar panels had deployed. Then the automatic attitude control system began malfunctioning and eventually failed completely, resulting in the craft spinning wildly. Komarov was able to stop the spin with the manual system, which was only partially effective. The flight controllers aborted his mission after only one day, and he made an emergency re-entry.

During re-entry a fault in the landing parachute system caused the primary chutes to fail, and the reserve chutes tangled together; Komarov was killed on impact.

Fixing these, and other, spacecraft faults caused an eighteen-month delay before piloted Soyuz flights could resume, similar to the US experience with Apollo. This, combined with Korolev's death, led to the quick unraveling of the Soviet Moon-landing program.

Other astronauts died while training for space flight, including four Americans (Ted Freeman, Elliot See, Charlie Bassett

Charles Bassett

Charles Arthur "Art" Bassett, II was an American engineer and United States Air Force officer. He was selected as a NASA astronaut in 1963 and assigned to Gemini 9 but died in an airplane crash during training for his first spaceflight.-Early life and education:Bassett was born in Dayton, Ohio,...

, Clifton Williams

Clifton Williams

This article is about the American astronaut. For the composer, see Clifton Williams .Clifton Curtis 'C.C.' Williams was a NASA astronaut, a Naval Aviator, and a Major in the United States Marine Corps who was killed in a plane crash; he had never been to space...

), who all died in crashes of T-38

T-38 Talon

The Northrop T-38 Talon is a twin-engine supersonic jet trainer. It was the world's first supersonic trainer and is also the most produced. The T-38 remains in service as of 2011 in air forces throughout the world....

aircraft. Yuri Gagarin, the first man in space, met a similar fate in 1968, when he crashed in a MiG-15

Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-15

The Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-15 was a jet fighter developed for the USSR by Artem Mikoyan and Mikhail Gurevich. The MiG-15 was one of the first successful swept-wing jet fighters, and it achieved fame in the skies over Korea, where early in the war, it outclassed all straight-winged enemy fighters in...

jet while training for a Soyuz mission. During the Apollo 15 mission in August 1971, the astronauts left behind a memorial

Fallen Astronaut

Fallen Astronaut is an 8.5 cm aluminium sculpture of an astronaut in a spacesuit which commemorates astronauts and cosmonauts who died in the advancement of space exploration...

in honor of all the people, both from the Soviet Union and the United States, who had perished during efforts to reach the moon. This included the Apollo 1 and Soyuz 1 crews, as well as astronauts and cosmonauts killed while in training.

In 1971, Soyuz 11 cosmonauts Georgi Dobrovolski, Viktor Patsayev

Viktor Patsayev

Viktor Ivanovich Patsayev was a Soviet cosmonaut who flew on the Soyuz 11 mission and had the unfortunate distinction of being part of the second crew to die during a space flight...

, and Vladislav Volkov

Vladislav Volkov

Vladislav Nikolayevich Volkov was a Soviet cosmonaut who flew on the Soyuz 7 and Soyuz 11 missions. The second mission terminated fatally.-Biography:...

asphyxiated during reentry. Since 1971, the Soviet/Russian space program has suffered no additional losses.

To the Moon

The United States recovered from the Apollo 1 fire, fixing the fatal flaws in an improved version of the Block II command module. The US proceeded with automated test launches of the Saturn VSaturn V

The Saturn V was an American human-rated expendable rocket used by NASA's Apollo and Skylab programs from 1967 until 1973. A multistage liquid-fueled launch vehicle, NASA launched 13 Saturn Vs from the Kennedy Space Center, Florida with no loss of crew or payload...

launch vehicle and Lunar Module lander during the latter-half of 1967 and early 1968. Apollo 1's mission was to have been to check out the first piloted Apollo spacecraft in Earth orbit. This mission was completed by Grissom's backup crew, commanded by Walter Schirra

Wally Schirra

Walter Marty Schirra, Jr. was an American test pilot, United States Navy officer, and one of the original Mercury 7 astronauts chosen for the Project Mercury, America's effort to put humans in space. He is the only person to fly in all of America's first three space programs...

on Apollo 7

Apollo 7

Apollo 7 was the first manned mission in the American Apollo space program, and the first manned US space flight after a cabin fire killed the crew of what was to have been the first manned mission, AS-204 , during a launch pad test in 1967...

, launched on 11 October 1968. The eleven-day mission was a total success, as the spacecraft performed a virtually flawless mission, paving the way for the United States to continue with its lunar mission schedule.

The Soviet Union also fixed the parachute and control problems with Soyuz, and the next piloted mission Soyuz 3

Soyuz 3

Soyuz 3 was a spaceflight mission launched by the Soviet Union on October 26, 1968. For four consecutive days, Commander Georgy Beregovoy piloted the Soyuz 7K-OK spacecraft through eighty-one orbits of Earth.-Crew:-Backup crew:...

was launched on 26 October 1968. The goal was to complete Komarov's rendezvous and docking mission with the un-piloted Soyuz 2. Ground controllers brought the two craft to within 200 metres (656.2 ft) of each other, then cosmonaut Georgy Beregovoy took control. He got within 40 metres (131.2 ft) of his target, but was unable to dock before expending 90 percent of his maneuvering fuel, due to a piloting error that put his spacecraft into the wrong orientation and forced Soyuz 2 to automatically turn away from his approaching craft.

The Soviet Zond spacecraft was almost ready for piloted circumlunar missions in 1968, although testing was not yet complete. At the time, the Soyuz 7K-L1/Zond spacecraft

Soyuz 7K-L1

The Soyuz 7K-L1 spacecraft was designed to launch men from the Earth to circle the Moon without going into lunar orbit in the context of the Soviet manned moon-flyby program in Moon race. It was based on the Soyuz 7K-OK with several components stripped out to reduce the vehicle weight...