Russian Civil War

Encyclopedia

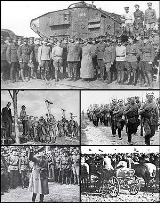

The Russian Civil War (1917–1923) was a multi-party war that occurred within the former Russian Empire

after the Russian provisional government

collapsed to the Soviets

, under the domination of the Bolshevik

party. Soviet forces first assumed power in Petrograd (St. Petersburg) and subsequently gained control throughout Russia

.

Principally, the Bolshevik Red Army

, often in temporary alliance with other leftist pro-revolutionary groups, fought against the White Army

, the loosely-allied anti-Bolshevik forces. Many foreign armies warred against the Red Army, notably the Allied Forces

, and many volunteer foreigners fought on both sides of the Russian Civil War. The Polish–Soviet War is often viewed as a theatre

of the conflict. Other nationalist and regional political groups also participated in the war, including the Ukrainian nationalist Green Army, the Ukrainian anarchist Black Army

and Black Guards

, and warlords such as Ungern von Sternberg.

The most intense fighting took place from 1918–20. Major military operations ended on 25 October 1922 when the Red Army occupied Vladivostok

, previously held by the Provisional Priamur Government. The last enclave of the White Forces was the Ayano-Maysky District

on the Pacific coast, where General Anatoly Pepelyayev

did not capitulate until 17 June 1923.

In Soviet historiography

the period of the Civil War has traditionally been defined as 1918–21, but the war's skirmishes actually stretched from 1917–23.

, the Russian Provisional Government

was established during the February Revolution

of 1917. In the following October Revolution

, the Red Guard

, armed groups of workers and deserting soldiers directed by the Bolshevik Party, seized control of Saint Petersburg

(then known as Petrograd) and began an immediate armed takeover of cities and villages throughout the former Russian Empire

. In January 1918, the Bolsheviks had the Russian Constituent Assembly

dissolved, proclaiming the Soviet

s as the new government of Russia.

The Bolsheviks decided to make peace immediately with the German Empire

and the Central Powers

, as they had promised the Russian people prior to the Revolution. Vladimir Lenin

's political enemies attributed this decision to his sponsorship by the foreign office of Wilhelm II, German Emperor, offered by the latter in hopes that with a revolution, Russia would withdraw from World War I

. This suspicion was bolstered by the German Foreign Ministry's sponsorship of Lenin's return to Petrograd

,but after the fiasco of the Kerensky's Provisional Government summer (June 1917) offensive the promise of peace had become an all powerful one for Lenin That last offensive of the Provisional Government left the Army's structure completely devastated. Even before the summer offensive the Russian population was highly sceptical about the continuation of the war. Western socialists had arrived promptly from France and UK to convince the Russians to continue the fight but couldn't change the new pacifist mood.

conceded huge portions of the former Russian Empire to the German Empire

and the Ottoman Empire

, greatly upsetting nationalists and conservative

s. Leon Trotsky

, representing the Bolsheviks, refused at first to sign the treaty while continuing to observe a unilateral cease fire, following the policy of "No war, no peace".

In view of this, on 18 February 1918, the Germans began an all-out advance on the Eastern Front, encountering virtually no resistance in a campaign that lasted 11 days. Signing a formal peace treaty was the only option in the eyes of the Bolsheviks, because the Russian army was demobilized and the newly-formed Red Guard were incapable of stopping the advance. They also understood that the impending counterrevolutionary resistance was more dangerous than the concessions of the treaty, which Lenin viewed as temporary in the light of aspirations for a world revolution

.

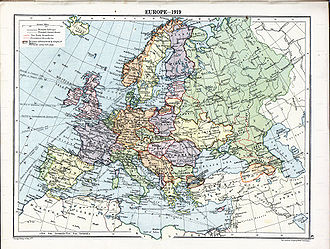

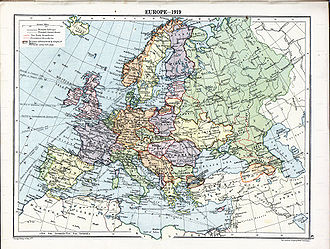

The Soviets acceded to a peace treaty and the formal agreement, the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

, was ratified on 6 March. The Soviets viewed the treaty as merely a necessary and expedient means to end the war. Therefore, they ceded large amounts of territory to the German Empire, which created several short-lived satellite

buffer state

s within its sphere of influence in Finland

(the "Kingdom of Finland

"), Estonia

and Latvia

("United Baltic Duchy

"), Courland

(the "Duchy of Courland and Semigallia

"), Lithuania

(the "Kingdom of Lithuania

"), Poland

(the "Kingdom of Poland

"), Belarus

(the "Belarusian People’s Republic"), Ukraine

(the "Hetmanate"), and Georgia

, Armenia

, and Azerbaijan

(the "Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic

"). Following the defeat of Germany in World War I, the Soviets eventually recovered the territories they gave up, with the exception of Finland, the Baltic States

, and Poland, which remained independent until the onset of World War II

.

In the wake of the October Revolution

, the old Russian Imperial Army had been demobilized; the volunteer-based Red Guard was the Bolsheviks' main military force, augmented by an armed military component of the Cheka

, the Bolshevik state security apparatus. In January, after significant reverses in combat, War Commissar Leon Trotsky headed the reorganization of the Red Guard into a Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, in order to create a more professional fighting force. Political commissars were appointed to each unit of the army to maintain morale and ensure loyalty.

In June 1918, when it became apparent that a revolutionary army composed solely of workers would be far too small, Trotsky instituted mandatory conscription of the rural peasantry into the Red Army. Opposition of rural Russians to Red Army conscription units was overcome by taking hostages and shooting them when necessary in order to force compliance, exactly the same practices used by the White Army officers too. Former Tsarist officers were utilized as "military specialists" (voenspetsy), sometimes taking their families hostage in order to ensure loyalty. At the start of the war, ¾ of the Red Army officer corps was composed of former Tsarist officers. By its end, 83% of all Red Army divisional and corps commanders were ex-Tsarist soldiers.

In the elections to the Constituent Assembly, the Bolsheviks constituted a minority of the vote and dissolved it. In general, they had support primarily in the Petrograd

and Moscow

Soviets and some other industrial regions.

While resistance to the Red Guard began on the very next day after the Bolshevik uprising, the Brest-Litovsk treaty and the political ban became a catalyst for the formation of anti-Bolshevik groups both inside and outside Russia, pushing them into action against the new regime.

A loose confederation of anti-Bolshevik forces aligned against the Communist government, including land-owners, republicans

, conservatives, middle-class citizens, reactionaries

, pro-monarchists, liberals, army generals, non-Bolshevik socialists who still had grievances and democratic reformists, voluntarily united only in their opposition to Bolshevik rule. Their military forces, bolstered by forced conscriptions and terror and by foreign influence and led by General Yudenich, Admiral Kolchak and General Denikin, became known as the White movement

(sometimes referred to as the "White Army"), and they controlled significant parts of the former Russian empire for most of the war.

A Ukrainian

nationalist movement known as the Green Army was active in Ukraine in the early part of the war. More significant was the emergence of an anarchist political and military movement known as the Revolutionary Insurrectionary Army of Ukraine

or the Anarchist Black Army

led by Nestor Makhno

. The Black Army, which counted numerous Jews and Ukrainian peasants in its ranks, played a key part in halting General Denikin's White Army offensive towards Moscow during 1919, later ejecting Cossack forces from the Crimea.

The Western Allies

also expressed their dismay at the Bolsheviks, (1) upset at the withdrawal of Russia from the war effort, (2) worried about a possible Russo-German alliance, and perhaps most importantly (3) galvanised by the prospect of the Bolsheviks making good their threats to assume no responsibility for, and so default on, Imperial Russia's massive foreign loans

; the legal notion of odious debt

had not yet been formulated. In addition, there was a concern, shared by many Central Powers

as well, that the socialist revolutionary ideas would spread to the West. Hence, many of these countries expressed their support for the Whites, including the provision of troops and supplies. Winston Churchill

declared that Bolshevism must be "strangled in its cradle".

The majority of the fighting ended in 1920 with the defeat of General Pyotr Wrangel in the Crimea

, but a notable resistance in certain areas continued until 1923 (e.g. Kronstadt Uprising, Tambov Rebellion

, Basmachi Revolt

, and the final resistance of the White movement in the Far East

).

The first period lasted from the Revolution until the Armistice. Already on the date of the Revolution, Cossack

General Kaledin refused to recognize it and assumed full governmental authority in the Don region, where the Volunteer Army

began amassing support. The signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

also resulted in direct Allied intervention in Russia and the arming of military forces opposed to the Bolshevik government. There were also many German commanders who offered support against the Bolsheviks, fearing a confrontation with them was impending as well.

During this first period, the Bolsheviks took control of Central Asia

out of the hands of the Provisional Government and White Army, setting up a base for the Communist Party in the Steppe and Turkestan, where nearly two million Russian settlers were located.

Most of the fighting in this first period was sporadic, involving only small groups amid a fluid and rapidly shifting strategic scene. Among the antagonists were the Czechoslovaks, known as the Czechoslovak Legion or "White Czechs", the Poles of the Polish 5th Rifle Division

and the pro-Bolshevik Red Latvian riflemen

.

The second period of the war lasted from January to November 1919. At first the White armies' advances from the south (under General Denikin), the east (under Admiral Kolchak) and the northwest (under General Yudenich

) were successful, forcing the Red Army and its leftist allies back on all three fronts. In July 1919, the Red Army suffered another reverse after a mass defection of Red Army units in the Crimea to the anarchist Black Army under Nestor Makhno

, enabling anarchist forces to consolidate power in Ukraine.

Leon Trotsky soon reformed the Red Army, concluding the first of two military alliances with the anarchists. In June, the Red Army first checked Kolchak's advance. After a series of engagements, assisted by a Black Army offensive against White supply lines, the Red Army defeated Denikin's and Yudenich's armies in October and November.

The third period of the war was the extended siege of the last White forces in the Crimea

. Wrangel

had gathered the remnants of the Denikin's armies, occupying much of the Crimea. An attempted invasion of southern Ukraine was rebuffed by the anarchist Black Army under the command of Nestor Makhno. Pursued into the Crimea by Makhno's troops, Wrangel went over to the defensive in the Crimea. After an abortive move north against the Red Army, Wrangel's troops were forced south by Red Army and Black Army forces; Wrangel and the remains of his army were evacuated to Constantinople

in November 1920.

The last period of 1921–1923 was characterized by three main events. The first was the defeat and liquidation of Nestor Makhno's anarchist Black Army, together with various other allied dissident leftist movements in Russia. The second was the escalation of peasant uprisings, which had commenced in 1918, but were fueled by the disbandment of local self-government in Ukraine and the demobilization of the Red Army. The last was the continued resistance of White Army, Islamic (Basmachi

), and autonomous nationalist forces against Bolshevik rule in Eastern Siberia (Transbaikalia, Yakutia), Central Asia

, and the Russian Far East

. In Soviet historiography the end of the Civil War is dated by the fall of Vladivostok

on 25 October 1922, though armed hostilities in the far provinces against Bolshevist rule continued into 1923.

in October 1917. It was supported by the Junker mutiny

in Petrograd, but quickly put down by the Red Guards, notably the Latvian rifle Division under I.I. Vatsetis.

The initial groups that fought against the Communists were local Cossack

armies that had declared their loyalty to the Provisional Government. Prominent among them were Kaledin

of the Don Cossacks

and Semenov of the Siberia

n Cossacks. The leading Tsarist officers of the old regime also started to resist. In November, General Alekseev, the Tsar's Chief-of-Staff during the First world war, began to organize a Volunteer Army

in Novocherkassk

. Volunteers of this small army were mostly officers of the old Russian army, military cadets and students. In December 1917, Alekseev was joined by Kornilov, Denikin and other Tsarist officers who had escaped from the jail where they had been imprisoned following the abortive Kornilov affair

just before the Revolution. At the beginning of December 1917, groups of volunteers and Cossacks captured Rostov

.

”, that any nation under imperial Russian rule should be immediately given the power of self-determination, the Bolsheviks had begun to usurp the power of the Provisional Government in the territories of Central Asia soon after the establishment of the Turkestan Committee in Tashkent. In April 1917, the Provisional Government set up this committee, which was mostly made up of former tsarist officials. The Bolsheviks attempted to take control of the Committee in Tashkent on September 12, 1917, but their mission was unsuccessful and many Bolshevik leaders were arrested. However, because the Committee lacked representation of the native population and poor Russian settlers, they had to release the Bolshevik prisoners almost immediately due to public outcry and a successful takeover of this government body took place two months later in November. The success of the Bolshevik party over the Provisional Government during 1917 was mostly due to the support they received from the working class of Central Asia. The Leagues of Mohammedam Working People, which Russian setters and natives who had been sent to work behind the lines for the Tsarist government in 1916 formed in March 1917, had led numerous strikes in the industrial centers throughout September 1917.

However, after the Bolshevik destruction of the Provisional Government in Tashkent, Muslim elites formed an autonomous government in Turkestan, commonly called the ‘Kokand autonomy’ (or simply Kokand). The White Russians supported this government body, which lasted several months because of Bolshevik troop isolation from Moscow.

, where the Central Rada of the Ukrainian People's Republic

held power. With the help of a revolt by workers in the Arsenal plant within Kiev

, the city was captured by the Bolsheviks on 26 January. As Civil War became a reality, the Bolshevik government decided to replace the provisional Red Guard

with a permanent Communist army: the Red Army

. The Council of People's Commissars formed the new army by decree

on 28 January 1918, initially basing its organization on that of the Red Guard.

Rostov was recaptured by the Soviets from the Don Cossacks on 23 February 1918. The day before, the Volunteer Army embarked on the epic Ice March

to the Kuban

, where they joined with the Kuban Cossacks

to mount an abortive assault on Ekaterinodar. General Kornilov was killed in the fighting on 13 April. Following Kornilov's death, General Denikin took over the command. Fighting off its pursuers without respite, the army succeeded in breaking its way through back towards the Don, where the Cossack uprising against Bolsheviks had started.

On 18 February, as peace negotiations between the Bolshevik government and the Germans broke down, the Germans began an all out advance into the interior of Russia, encountering virtually no resistance in a campaign which lasted 11 days. Despite mass recruitment of new conscripts, the newly-formed Red Army proved incapable of stopping the advance and the Soviets acceded to a punitive peace treaty. The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

(3 March 1918) which pulled Russia out of the war and gave Germany control over vast stretches of western Russia; this came as a shock to the Allies.

The massive uprising of the Don Cossacks

against the Bolsheviks took place in the beginning of April 1918. Their military council elected general Pyotr Krasnov

as their Ataman. Don Army

was formed.

The British and the French had supported Russia on a massive scale with war materials. After the treaty, it looked like much of that material would fall into the hands of the Germans. Under this pretext began allied intervention in the Russian Civil War

with the United Kingdom

and France

sending troops into Russian ports. There were violent confrontations with troops loyal to the Bolsheviks.

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with the Germans formally ended the war on the Eastern Front. This permitted the redeployment of German soldiers to the Western Front. Then in mid-April, the Cheka

made mass arrests of anarchists in a night raid in Petrograd. This was followed up with simultaneous raids against anarchists in Petrograd and Moscow at the end of April.

The Baku Commune was established on 13 April and lasted until 25 July 1918. The Baku Red Army successfully resisted the Ottoman Army of Islam, and was obliged to retreat to Baku. However, the Dashanak

s, Right SRs and Menshevik

s started negotiations with General Dunsterville, the commander of the British

troops in Persia. The Bolsheviks and their Left SR allies were opposed to it but, on 25 July the majority of the Soviet voted to call in the British and the Bolsheviks resigned. The Baku Commune ended its existence and was replaced by the Central Caspian Dictatorship.

In June 1918, "white" Volunteer army

, numbering some 9000 men, started its second Kuban campaign. Ekaterinodar was encircled on 1 August and fell on the 3rd. In September–October, heavy fighting took place at Armavir and Stavropol

. On 13 October, General Kazanovich's division took Armavir and on November 1, general Pyotr Wrangel secured Stavropol. This time red forces had no escape and by the beginning of 1919, the whole Northern Caucasus was free from bolsheviks.

In October, General Alekseev, the leader for the White armies in Southern Russia, died of a heart attack and was replaced by General Denikin.

On 26 December 1918, agreement was reached between A.I. Denikin, head of the Volunteer Army, And P.N. Krasnov, Ataman of the Don Cossacks, which united their forces under the sole command of Denikin. The Armed Forces of South Russia

were created, uniting Volunteer Army and Cossack forces.

At the end of May, a marked escalation of the conflict was signalled by the unexpected intervention of the Czechoslovak Legion

. The Czech Legion had been part of the Russian army and numbered around 30,000 troops by October 1917. An agreement with the new Bolshevik government to pass by sea through Vladivostok

(so they could unite with the Czechoslovak legions

in France) collapsed over an attempt to disarm the Corps. Instead, their soldiers disarmed the Bolshevik forces in June 1918 at Cheliabinsk. At the same time as the Czechs moved in, Russian officers' organizations overthrew the Bolsheviks in Petropavl

ovsk and Omsk

. Within a month the Whites controlled most of the Trans-Siberian Railroad from Lake Baikal

to the Ural Mountains

regions. During the summer, the Bolshevik power in Siberia was totally wiped out. Provisional Siberian Government

was formed in Omsk

.

By the end of July, Whites had extended their gains, capturing Ekaterinburg on 26 July 1918. Shortly before the fall of Ekaterinburg (on 17 July 1918), the former Tsar and his family were executed by the Ural Soviet, ostensibly to prevent them falling into the hands of the Whites.

The Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries supported peasant

fighting against Soviet control of food supplies. In May 1918, with the support of the Czechoslovak Legion, they took Samara

and Saratov

, establishing the Committee of Members of the Constituent Assembly. By July, the authority of Komuch extended over much of the area controlled by the Czechoslovak Legion. The Komuch pursued an ambivalent social policy, combining democratic and even socialist measures, such as the institution of an eight-hour working day, with "restorative" actions, such as returning both factories and land to their former owners.

In July, two left Socialist-Revolutionaries and Cheka employees, Blyumkin

and Andreyev, assassinated the German ambassador, Count Mirbach

. In Moscow Left SR uprising was put down by Bolsheviks, using military detachments from the Cheka. Lenin personally apologised to the Germans for the assassination. Mass arrests of Socialist-Revolutionaries followed.

After a series of reverses at the front, War Commissar Trotsky instituted increasingly harsh measures in order to prevent unauthorized withdrawals, desertions, or mutinies in the Red Army. In the field, the dreaded Cheka special investigations forces, termed the Special Punitive Department of the All-Russian Extraordinary Commission for Combat of Counter-Revolution and Sabotage, or Special Punitive Brigades followed the Red Army, conducting field tribunals and summary executions of soldiers and officers who either deserted, retreated from their positions, or who failed to display sufficient offensive zeal. The use of the death penalty was extended by Trotsky to the occasional political commissar whose detachment retreated or broke in the face of the enemy. In August, frustrated at continued reports of Red Army troops breaking under fire, Trotsky authorized the formation of anti-retreat detachments

stationed behind unreliable Red Army units, with orders to shoot anyone withdrawing from the battle line without authorization.

In September 1918, Komuch, Siberian Provisional Government and other local anti-Soviet governments met in Ufa

and agreed to form a new Provisional All-Russian Government

in Omsk, headed by a Directory of five: three Socialist-Revolutionaries (Nikolai Avksentiev

, Boldyrev and Vladimir Zenzinov

) and two Kadets

, (V. A. Vinogradov and P. V. Vologodskii).

By the fall of 1918, Anti-Bolshevik White Forces in the East included the People's Army (Komuch), the Siberian Army (of the Siberian Provisional Government) and insurgent Cossack units of Orenburg, Ural, Siberia, Semirechye, Baikal, Amur and Ussuri Cossacks, nominally under the orders of general V.G. Boldyrev, Commander-in-Chief, appointed by the Ufa Directorate.

On the Volga, Kazan

was captured by the colonel Kappel

detachement on 7 August, but was recaptured by the Reds on September 8, following the Red counter-offensive. On the 11th, Simbirsk fell; and on 8 October, Samara

. The Whites fell back to Ufa and Orenburg.

In Omsk, the Russian Provisional Government quickly came under the influence of the new War Minister, Rear-Admiral Kolchak. On 18 November, a coup d'état

established Kolchak as dictator. The members of the Directory were arrested and Kolchak proclaimed the "Supreme Ruler of Russia".

By mid-December 1918, White armies in the East had to leave Ufa

but this failure was balanced by the successful drive towards Perm

. Perm was taken on 24 December.

, leading the Malleson Mission

, assisted the Mensheviks in Ashkhabad (now the capital of Turkmenistan) with a small Anglo-Indian force. However, he failed to gain control of Tashkent, Bukhara, and Khiva. The third was Major-General Dunsterville

, who the Bolsheviks drove out of Central Asia only a month after his arrival in August 1918. Despite setbacks due to British invasions during 1918, the Bolsheviks continued to make progress in bringing the Central Asian population under the influence of their party. The first regional congress of the Russian Communist Party convened in the city of Tashkent in June 1918 in order to build support for a local Bolshevik Party.

The stage was now set for the key year of the Civil War. The Bolshevik government was firmly in control of the core of Russia, from Petrograd through Moscow and south to Tsaritsyn

The stage was now set for the key year of the Civil War. The Bolshevik government was firmly in control of the core of Russia, from Petrograd through Moscow and south to Tsaritsyn

(now Volgograd). Against this government in the east, Admiral Kolchak had a small army and had some control over the Trans-Siberian Railroad. In the south, the White Armies controlled much of the Don and Ukraine. In the Caucasus, General Denikin had established a new White army.

The British occupied Murmansk

and the British and the American

s occupied Arkhangelsk

. Newly established Estonia cleared its territory from the Soviets by January 1919. French forces landed in Odessa

, but after having done almost no fighting, withdrew their troops on 8 April 1919. The Japan

ese occupied Vladivostok

.

-Chistopol

-Bugulma

-Buguruslan

-Sharlyk line. Reds started their counter-offensive against Kolchak's forces at the end of April. Red army, led by the capable commander Tukhachevsky, captured Elabuga on 26 May, Sarapul

on 2 June, and Izevsk on the 7th, and continued to push forward. Both sides had victories and losses, but by the middle of summer the Red army was larger than the White army and had managed to recapture territory previously lost.

Following the abortive offensive at Chelyabinsk

, the White armies withdrew beyond Tobol. In September 1919, White offensive was launched against Tobol, the last attempt to change the course of events. But on 14 October, the Reds counterattacked and then began the uninterrupted retreat of the Whites to the East

.

On 14 November 1919, the Red Army captured Omsk

. Admiral Kolchak lost control of his government shortly after this defeat; White Army forces in Siberia essentially ceased to exist by December. Retreat of the Eastern front White armies lasted three months, until mid-February 1920, when the survivors, after crossing the Baikal

, reached the Chita

area and joined Ataman Semenov forces.

With the retreat of Kolchak's White Army, Great Britain and the U.S. pulled their troops out of Murmansk

and Arkhangelsk

before the onset of winter trapped their forces in port.

counter-offensive began in January 1919 under the Bolshevik leader Antonov-Ovseenko

, the Cossack forces rapidly fell apart. The Red Army captured Kiev on 3 February 1919.

Denikin's military strength continued to grow in the spring of 1919. During the several months in winter and spring of 1919, hard fighting with doubtful outcomes took place in the Donets basin

Denikin's military strength continued to grow in the spring of 1919. During the several months in winter and spring of 1919, hard fighting with doubtful outcomes took place in the Donets basin

where the attacking Bolsheviks met White forces. At the same time, Denikin's Armed Forces of South Russia

(AFSR) completed the elimination of red forces in the Northern Caucasus and advanced towards Tsaritsyn. At the end of April and beginning of May, the AFSR attacked on all fronts from the Dnepr to the Volga and at the beginning of the summer they had won numerous battles. By mid-June the Reds were chased from the Crimea and from the Odessa area. Denikin's troops took the cities of Kharkov and Belgorod

. At the same time White troops under command of General Wrangel took Tsaritsyn on 17 June 1919. On 20 June, Denikin issued his famous "Moscow directive", ordering all AFSR units to get ready for a decisive offensive to take Moscow.

Although Great Britain had withdrawn its own troops from the theater, it continued to give significant military aid (money, weapons, food, ammunition, and some military advisors) to the White armies during 1919, especially to General Yudenich. Despite large quantities of aid given to White commanders by Allied nations, many White commanders expressed dissatisfaction with the amount of aid given. Yudenich in particular complained that he was receiving insufficient support.

After capture of Tsaritsyn, Wrangel pushed towards Saratov

, but Trotsky, seeing the danger of the union with Kolchak

, against whom the Red command was concentrating large masses of troops, repulsed his attempts with heavy losses. When the Kolchak's army in the East began to retreat in June and July, the bulk of the Red army, free now from any serious danger from Siberia, was directed against Denikin.

Denikin's forces constituted a real threat, and for a time threatened to reach Moscow. The Red Army, stretched thin by fighting on all fronts, was forced out of Kiev on 30 August. Kursk

and Orel

were taken. The Cossack Don Army

under the command of General Mamontov continued north towards Voronezh

, but there Tukhachevsky's army defeated them on 24 October. Tukhachevsky's army then turned toward yet another threat, the rebuilt Volunteer Army

of General Denikin.

The high tide of the White movement against the Soviets had been reached in September 1919. By this time Denikin's forces were dangerously overextended. The White front had no depth or stability: it had become a series of patrols with occasional columns of slowly advancing troops without reserves. Lacking ammunition, artillery, and fresh reinforcements, Denikin's army was decisively defeated in a series of battles in October and November 1919. The Red Army recaptured Kiev on 17 December and the defeated Cossacks fled back towards the Black Sea

.

While the White Armies were being routed in the center and the east, they had succeeded in driving Nestor Makhno

's anarchist Black Army (formally known as the Revolutionary Insurrectionary Army of Ukraine

) out of part of southern Ukraine and the Crimea. Despite this setback, Moscow was loath to aid Makhno and the Black Army, and refused to provide arms to anarchist forces in Ukraine.

The main body of White forces, the Volunteers and the Don Army pulled back towards the Don, to Rostov. The smaller body (Kiev and Odessa troops) withdrew to Odessa and the Crimea, which it had managed to protect from the Bolsheviks during the winter of 1919-1920.

In the meantime, the Red Army turned to deal with a new threat. This one came from White Army General Yudenich, who had spent the spring and summer organizing a small army in Estonia

In the meantime, the Red Army turned to deal with a new threat. This one came from White Army General Yudenich, who had spent the spring and summer organizing a small army in Estonia

, with Estonian and British support. In October 1919, he tried to capture Petrograd in a sudden assault with a force of around 20,000 men. The attack was well-executed, using night attacks and lightning cavalry maneuvers to turn the flanks of the defending Red army. Yudenich also had six British tanks that caused panic whenever they appeared.

By 19 October, Yudenich's troops had reached the outskirts of Petrograd. Some members of the Bolshevik central committee in Moscow were willing to give up Petrograd, but Trotsky refused to accept the loss of the city and personally organized its defenses. Trotsky declared, "It is impossible for a little army of 15,000 ex-officers to master a working class capital of 700,000 inhabitants." He settled on a strategy of urban defense, proclaiming that the city would "defend itself on its own ground" that the White Army would be lost in a labyrinth of fortified streets and there "meet its grave".

Trotsky armed all available workers, men and women, ordering the transfer of military forces from Moscow. Within a few weeks the Red army defending Petrograd had tripled in size and outnumbered Yudenich three to one. At this point Yudenich, short of supplies, decided to call off the siege of the city, withdrawing his army across the border to Estonia. Upon his return, his army was disarmed by order of the Estonian government, fearful of reprisals by Moscow and its Red Army War Commissar, which turned out to be well-founded. However, the Bolshevik forces pursuing Yudenich's forces (Yudenich based himself in Helsinki) were beaten back by the Estonian army. Following the Treaty of Tartu

most of Yudenich's soldiers went into exile.

The Finnish general Mannerheim planned a Finnish intervention to help the whites in Russia capture Petrograd. In Finland the whites had recently won their own civil war

against the reds. He did not, however, gain the necessary support for the endeavor. Had the Finns intervened, the effects could have been decisive. Lenin considered it "completely certain, that the slightest aid from Finland would have determined the fate of Petrograd". Trotsky anticipated the events leading to the Winter War

by saying "We cannot live, year after year, under the persisting threat that general Mannerheim, or someone else decides to take Petrograd from us."

Communication difficulties with the Red Army forces in Siberia and European Russia ceased to be a problem by mid-November 1919. Due to Red Army success north of Central Asia, communication with Moscow was re-established and the Bolsheviks were able to claim victory over the White Army in Turkestan.

as the new leader of the White Army in Siberia. Not long after this, Kolchak was arrested by the disaffected Czechoslovak Corps as he traveled towards Irkutsk

without the protection of the army and turned over to the socialist Political Centre

in Irkutsk. Six days later, this regime was replaced by a Bolshevik dominated Military-Revolutionary Committee. On 6–7 February, Kolchak and his prime minister Victor Pepelyaev were shot and their bodies thrown through the ice of a frozen river, just before the arrival of the White Army in the area.

Remnants of Kolchak's army reached Transbaikalia and joined Grigory Semyonov

's troops, forming Far Eastern army. With the support of the Japanese Army, it was able hold Chita

, but after withdrawal of Japanese soldiers from Transbaikalia, Semenov's position become untenable and in November 1920 he was repulsed by the Red Army from Transbaikalia and took refuge in China.

was rapidly retreating towards the Don, to Rostov. Denikin hoped to hold the crossings of the Don, rest and reform his troops. But the White Army was not able to hold the Don area, and at the end of February 1920 started a retreat across Kuban towards Novorossiysk

. Slipshod evacuation of Novorossiysk proved to be a dark event for the White Army. About 40,000 men were evacuated by Russian and Allied ships from Novorossiysk to Crimea

, without horses or any heavy equipment, while about 20,000 men were left behind and either dispersed or captured by the Red Army.

Following the disastrous Novorossiysk evacuation, General Denikin stepped down, and General Pyotr Wrangel was elected new Commander-in-Chief of the White Army by military council. He was able to restore order with dispirited troops and reshape the army which could again fight as a regular force. His army remained an organized force in the Crimea throughout 1920.

After Moscow's Bolshevik government signed a military and political alliance with Nestor Makhno and the Ukrainian anarchists, the Black Army attacked and defeated several regiments of Wrangel's troops in southern Ukraine, forcing Wrangel

to retreat before he could capture that year's grain harvest.

Stymied in his efforts to consolidate his hold in Ukraine, General Wrangel then attacked north in an attempt to take advantage of recent Red Army defeats at the close of the Polish-Soviet War

of 1919-1920. This offensive was eventually halted by the Red Army, and Wrangel and his troops were forced to retreat to Crimea in November 1920, pursued by both Red and Black cavalry and infantry. Wrangel

and the remains of his army were evacuated from Crimea to Constantinople on 14 November 1920. Thus ended the struggle of Reds and Whites in Southern Russia.

and attacked the anarchist Black Army

; the campaign to liquidate Makhno and the Ukrainian anarchists began with an attempted assassination of Makhno by agents of the Cheka

. Red Army attacks on anarchist forces and their sympathizers increased in ferocity throughout 1921. As War Commissar of Red Army forces, Leon Trotsky

instituted mass executions of peasants in Ukraine and other areas sympathetic to Makhno and the anarchists. Angered by continued repression by the Bolshevik Communist government and its liberal use of the Cheka

to put down peasant and anarchist elements, a naval mutiny erupted at Kronstadt

, followed by peasant revolts in Ukraine, Tambov, and Siberia.

The Japanese, who had plans to annex the Amur Krai of Eastern Siberia, finally pulled their troops out as the Bolshevik forces gradually asserted control over all of Siberia

. On 25 October 1922, Vladivostok

fell to the Red Army and the Provisional Priamur Government was extinguished. General Anatoly Pepelyayev

continued armed resistance

in the Ayano-Maysky District

until June 1923. In central Asia, Red Army troops continued to face resistance into 1923, where basmachi

(armed bands of Islamic guerrillas) had formed to fight the Bolshevik takeover. The regions of Kamchatka and Northern Sakhalin

remained under Japanese occupation until their treaty with Soviet Union in 1925, when their forces were finally withdrawn. The Soviets engaged non-Russian peoples in Central Asia like Magaza Masanchi

, commander of the Dungan Cavalry Regiment to fight against the Basmachis.

During the Red Terror

, the Cheka

carried out an estimated 250,000 summary executions of "enemies of the people".

Some 300,000–500,000 Cossacks were killed or deported during Decossackization

, out of a population of around three million. An estimated 100,000 Jews were killed in Ukraine, mostly by the White Army. Punitive organs of the All Great Don Cossack Host

sentenced 25,000 people to death between May 1918 and January 1919. Kolchak's government shot 25,000 people in Ekaterinburg province alone.

At the end of the Civil War, the Russian SFSR was exhausted and near ruin. The droughts of 1920 and 1921, as well as the 1921 famine

, worsened the disaster still further. Disease had reached pandemic proportions, with 3,000,000 dying of typhus

alone in 1920. Millions more were also killed by widespread starvation, wholesale massacres by both sides, and pogroms against Jews in Ukraine and southern Russia. By 1922, there were at least 7,000,000 street children

in Russia as a result of nearly 10 years of devastation from the Great War

and the civil war.

Another one to two million people, known as the White émigrés, fled Russia—many with General Wrangel, some through the Far East, others west into the newly independent Baltic countries. These émigrés included a large part of the educated and skilled population of Russia.

Another one to two million people, known as the White émigrés, fled Russia—many with General Wrangel, some through the Far East, others west into the newly independent Baltic countries. These émigrés included a large part of the educated and skilled population of Russia.

The Russian economy was devastated by the war, with factories and bridges destroyed, cattle and raw materials pillaged, mines flooded, and machines damaged. The industrial production value descended to one seventh of the value of 1913, and agriculture to one third. According to Pravda

, "The workers of the towns and some of the villages choke in the throes of hunger. The railways barely crawl. The houses are crumbling. The towns are full of refuse. Epidemics spread and death strikes—industry is ruined."

It is estimated that the total output of mines and factories in 1921 had fallen to 20% of the pre–World War level, and many crucial items experienced an even more drastic decline. For example, cotton production fell to 5%, and iron to 2% of pre-war levels.

War Communism

saved the Soviet government during the Civil War, but much of the Russian economy had ground to a standstill. The peasants responded to requisitions

by refusing to till the land. By 1921, cultivated land had shrunk to 62% of the pre-war area, and the harvest yield was only about 37% of normal. The number of horses declined from 35 million in 1916 to 24 million in 1920, and cattle from 58 to 37 million. The exchange rate with the U.S. dollar declined from two rubles

in 1914 to 1,200 in 1920.

With the end of the war, the Communist Party no longer faced an acute military threat to its existence and power. However, the perceived threat of another intervention, combined with the failure of socialist revolutions in other countries, most notably the German Revolution

, contributed to the continued militarization of Soviet society. Although Russia experienced extremely rapid economic growth in the 1930s, the combined effect of World War I and the Civil War left a lasting scar in Russian society, and had permanent effects on the development of the Soviet Union

.

As the British historian Orlando Figes put it, at the root of the Whites' defeat was a failure of politics, more precisely their own dismal failure to break with the ugly past of the oppressive Tsarist régime.

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

after the Russian provisional government

Russian Provisional Government

The Russian Provisional Government was the short-lived administrative body which sought to govern Russia immediately following the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II . On September 14, the State Duma of the Russian Empire was officially dissolved by the newly created Directorate, and the country was...

collapsed to the Soviets

Soviet republic (system of government)

A Soviet Republic is a system of government in which the whole state power belongs to the Soviets . Although the term is usually associated with communist states, it was not initially intended to represent only one political force, but merely a form of democracy and representation.In the classic...

, under the domination of the Bolshevik

Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, originally also Bolshevists , derived from bol'shinstvo, "majority") were a faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party which split apart from the Menshevik faction at the Second Party Congress in 1903....

party. Soviet forces first assumed power in Petrograd (St. Petersburg) and subsequently gained control throughout Russia

Russia

Russia or , officially known as both Russia and the Russian Federation , is a country in northern Eurasia. It is a federal semi-presidential republic, comprising 83 federal subjects...

.

Principally, the Bolshevik Red Army

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army started out as the Soviet Union's revolutionary communist combat groups during the Russian Civil War of 1918-1922. It grew into the national army of the Soviet Union. By the 1930s the Red Army was among the largest armies in history.The "Red Army" name refers to...

, often in temporary alliance with other leftist pro-revolutionary groups, fought against the White Army

White movement

The White movement and its military arm the White Army - known as the White Guard or the Whites - was a loose confederation of Anti-Communist forces.The movement comprised one of the politico-military Russian forces who fought...

, the loosely-allied anti-Bolshevik forces. Many foreign armies warred against the Red Army, notably the Allied Forces

Allied Intervention in the Russian Civil War

The Allied intervention was a multi-national military expedition launched in 1918 during World War I which continued into the Russian Civil War. Its operations included forces from 14 nations and were conducted over a vast territory...

, and many volunteer foreigners fought on both sides of the Russian Civil War. The Polish–Soviet War is often viewed as a theatre

Theater (warfare)

In warfare, a theater, is defined as an area or place within which important military events occur or are progressing. The entirety of the air, land, and sea area that is or that may potentially become involved in war operations....

of the conflict. Other nationalist and regional political groups also participated in the war, including the Ukrainian nationalist Green Army, the Ukrainian anarchist Black Army

Revolutionary Insurrectionary Army of Ukraine

The Revolutionary Insurrectionary Army of Ukraine , popularly called Makhnovshchina, less correctly Makhnovchina, and also known as the Black Army, was an anarchist army formed largely of Ukrainian and Crimean peasants and workers under the command of the famous anarchist Nestor Makhno during the...

and Black Guards

Black Guards

Black Guards were armed groups of workers formed after the Russian Revolution and before the Third Russian Revolution. They were the main strike force of the anarchists...

, and warlords such as Ungern von Sternberg.

The most intense fighting took place from 1918–20. Major military operations ended on 25 October 1922 when the Red Army occupied Vladivostok

Vladivostok

The city is located in the southern extremity of Muravyov-Amursky Peninsula, which is about 30 km long and approximately 12 km wide.The highest point is Mount Kholodilnik, the height of which is 257 m...

, previously held by the Provisional Priamur Government. The last enclave of the White Forces was the Ayano-Maysky District

Ayano-Maysky District

Ayano-Maysky District is an administrative and municipal district , one of the seventeen in Khabarovsk Krai, Russia. Its administrative center is the rural locality of Ayan. District's population: Population of Ayan accounts for 40.5% of the district's population.-Geography:The district has...

on the Pacific coast, where General Anatoly Pepelyayev

Anatoly Pepelyayev

Anatoly Nikolayevich Pepelyayev was a White Russian general who led the Siberian armies of Admiral Kolchak during the Russian Civil War. His elder brother Viktor Pepelyayev served as Prime Minister in Kolchak's government.-Trans-Siberian march:...

did not capitulate until 17 June 1923.

In Soviet historiography

Soviet historiography

Soviet historiography is the methodology of history studies by historians in the Soviet Union . In the USSR, the study of history was marked by alternating periods of freedom allowed and restrictions imposed by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union , and also by the struggle of historians to...

the period of the Civil War has traditionally been defined as 1918–21, but the war's skirmishes actually stretched from 1917–23.

Context

After the abdication of Nicholas II of RussiaNicholas II of Russia

Nicholas II was the last Emperor of Russia, Grand Prince of Finland, and titular King of Poland. His official short title was Nicholas II, Emperor and Autocrat of All the Russias and he is known as Saint Nicholas the Passion-Bearer by the Russian Orthodox Church.Nicholas II ruled from 1894 until...

, the Russian Provisional Government

Russian Provisional Government

The Russian Provisional Government was the short-lived administrative body which sought to govern Russia immediately following the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II . On September 14, the State Duma of the Russian Empire was officially dissolved by the newly created Directorate, and the country was...

was established during the February Revolution

February Revolution

The February Revolution of 1917 was the first of two revolutions in Russia in 1917. Centered around the then capital Petrograd in March . Its immediate result was the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II, the end of the Romanov dynasty, and the end of the Russian Empire...

of 1917. In the following October Revolution

October Revolution

The October Revolution , also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution , Red October, the October Uprising or the Bolshevik Revolution, was a political revolution and a part of the Russian Revolution of 1917...

, the Red Guard

Red Guards (Russia)

In the context of the history of Russia and Soviet Union, Red Guards were paramilitary formations consisting of workers and partially of soldiers and sailors formed in the time frame of the Russian Revolution of 1917...

, armed groups of workers and deserting soldiers directed by the Bolshevik Party, seized control of Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg is a city and a federal subject of Russia located on the Neva River at the head of the Gulf of Finland on the Baltic Sea...

(then known as Petrograd) and began an immediate armed takeover of cities and villages throughout the former Russian Empire

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

. In January 1918, the Bolsheviks had the Russian Constituent Assembly

Russian Constituent Assembly

The All Russian Constituent Assembly was a constitutional body convened in Russia after the October Revolution of 1917. It is generally reckoned as the first democratically elected legislative body of any kind in Russian history. It met for 13 hours, from 4 p.m...

dissolved, proclaiming the Soviet

Soviet (council)

Soviet was a name used for several Russian political organizations. Examples include the Czar's Council of Ministers, which was called the “Soviet of Ministers”; a workers' local council in late Imperial Russia; and the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union....

s as the new government of Russia.

The Bolsheviks decided to make peace immediately with the German Empire

German Empire

The German Empire refers to Germany during the "Second Reich" period from the unification of Germany and proclamation of Wilhelm I as German Emperor on 18 January 1871, to 1918, when it became a federal republic after defeat in World War I and the abdication of the Emperor, Wilhelm II.The German...

and the Central Powers

Central Powers

The Central Powers were one of the two warring factions in World War I , composed of the German Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulgaria...

, as they had promised the Russian people prior to the Revolution. Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Lenin was a Russian Marxist revolutionary and communist politician who led the October Revolution of 1917. As leader of the Bolsheviks, he headed the Soviet state during its initial years , as it fought to establish control of Russia in the Russian Civil War and worked to create a...

's political enemies attributed this decision to his sponsorship by the foreign office of Wilhelm II, German Emperor, offered by the latter in hopes that with a revolution, Russia would withdraw from World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

. This suspicion was bolstered by the German Foreign Ministry's sponsorship of Lenin's return to Petrograd

Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg is a city and a federal subject of Russia located on the Neva River at the head of the Gulf of Finland on the Baltic Sea...

,but after the fiasco of the Kerensky's Provisional Government summer (June 1917) offensive the promise of peace had become an all powerful one for Lenin That last offensive of the Provisional Government left the Army's structure completely devastated. Even before the summer offensive the Russian population was highly sceptical about the continuation of the war. Western socialists had arrived promptly from France and UK to convince the Russians to continue the fight but couldn't change the new pacifist mood.

Beginning

On 16 December 1917, an armistice was signed between Russia and the Central Powers at Brest-Litovsk and peace talks began. As a condition for peace, the proposed treaty by the Central PowersCentral Powers

The Central Powers were one of the two warring factions in World War I , composed of the German Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulgaria...

conceded huge portions of the former Russian Empire to the German Empire

German Empire

The German Empire refers to Germany during the "Second Reich" period from the unification of Germany and proclamation of Wilhelm I as German Emperor on 18 January 1871, to 1918, when it became a federal republic after defeat in World War I and the abdication of the Emperor, Wilhelm II.The German...

and the Ottoman Empire

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

, greatly upsetting nationalists and conservative

Conservatism

Conservatism is a political and social philosophy that promotes the maintenance of traditional institutions and supports, at the most, minimal and gradual change in society. Some conservatives seek to preserve things as they are, emphasizing stability and continuity, while others oppose modernism...

s. Leon Trotsky

Leon Trotsky

Leon Trotsky , born Lev Davidovich Bronshtein, was a Russian Marxist revolutionary and theorist, Soviet politician, and the founder and first leader of the Red Army....

, representing the Bolsheviks, refused at first to sign the treaty while continuing to observe a unilateral cease fire, following the policy of "No war, no peace".

In view of this, on 18 February 1918, the Germans began an all-out advance on the Eastern Front, encountering virtually no resistance in a campaign that lasted 11 days. Signing a formal peace treaty was the only option in the eyes of the Bolsheviks, because the Russian army was demobilized and the newly-formed Red Guard were incapable of stopping the advance. They also understood that the impending counterrevolutionary resistance was more dangerous than the concessions of the treaty, which Lenin viewed as temporary in the light of aspirations for a world revolution

World revolution

World revolution is the Marxist concept of overthrowing capitalism in all countries through the conscious revolutionary action of the organized working class...

.

The Soviets acceded to a peace treaty and the formal agreement, the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was a peace treaty signed on March 3, 1918, mediated by South African Andrik Fuller, at Brest-Litovsk between Russia and the Central Powers, headed by Germany, marking Russia's exit from World War I.While the treaty was practically obsolete before the end of the year,...

, was ratified on 6 March. The Soviets viewed the treaty as merely a necessary and expedient means to end the war. Therefore, they ceded large amounts of territory to the German Empire, which created several short-lived satellite

Satellite state

A satellite state is a political term that refers to a country that is formally independent, but under heavy political and economic influence or control by another country...

buffer state

Buffer state

A buffer state is a country lying between two rival or potentially hostile greater powers, which by its sheer existence is thought to prevent conflict between them. Buffer states, when authentically independent, typically pursue a neutralist foreign policy, which distinguishes them from satellite...

s within its sphere of influence in Finland

Finland

Finland , officially the Republic of Finland, is a Nordic country situated in the Fennoscandian region of Northern Europe. It is bordered by Sweden in the west, Norway in the north and Russia in the east, while Estonia lies to its south across the Gulf of Finland.Around 5.4 million people reside...

(the "Kingdom of Finland

Kingdom of Finland (1918)

The Kingdom of Finland was an abortive attempt to establish a monarchy in Finland, following Finland's independence from Russia. Had the German Empire endured, Prince Frederick Charles of Hesse would have been installed as King of Finland.-History:...

"), Estonia

Estonia

Estonia , officially the Republic of Estonia , is a state in the Baltic region of Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland, to the west by the Baltic Sea, to the south by Latvia , and to the east by Lake Peipsi and the Russian Federation . Across the Baltic Sea lies...

and Latvia

Latvia

Latvia , officially the Republic of Latvia , is a country in the Baltic region of Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by Estonia , to the south by Lithuania , to the east by the Russian Federation , to the southeast by Belarus and shares maritime borders to the west with Sweden...

("United Baltic Duchy

United Baltic Duchy

The proposed United Baltic Duchy also known as the Grand Duchy of Livonia was a state proposed by the Baltic German nobility and exiled Russian nobility after the Russian revolution and German occupation of the Courland, Livonian and Estonian governorates of the Russian Empire.The idea comprised...

"), Courland

Courland

Courland is one of the historical and cultural regions of Latvia. The regions of Semigallia and Selonia are sometimes considered as part of Courland.- Geography and climate :...

(the "Duchy of Courland and Semigallia

Duchy of Courland and Semigallia (1918)

The Duchy of Courland and Semigallia was a proposed Client state of the German Empire. It was proclaimed on March 8, 1918, in German-occupied Courland Governorate by a Landesrat composed of Baltic Germans, who offered the crown of the Duchy to Kaiser Wilhelm II, despite the existence of a former...

"), Lithuania

Lithuania

Lithuania , officially the Republic of Lithuania is a country in Northern Europe, the biggest of the three Baltic states. It is situated along the southeastern shore of the Baltic Sea, whereby to the west lie Sweden and Denmark...

(the "Kingdom of Lithuania

Kingdom of Lithuania (1918)

The Kingdom of Lithuania was a short-lived constitutional monarchy created towards the end of World War I when Lithuania was under occupation by the German Empire. The Council of Lithuania declared Lithuania's independence on February 16, 1918, but the Council was unable to form a government,...

"), Poland

Poland

Poland , officially the Republic of Poland , is a country in Central Europe bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania to the east; and the Baltic Sea and Kaliningrad Oblast, a Russian exclave, to the north...

(the "Kingdom of Poland

Kingdom of Poland (1916–1918)

The Kingdom of Poland, also informally called the Regency Kingdom of Poland , was a proposed puppet state during World War I by Germany and Austria-Hungary in 1916 after their conquest of the former Congress Poland from Russia...

"), Belarus

Belarus

Belarus , officially the Republic of Belarus, is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe, bordered clockwise by Russia to the northeast, Ukraine to the south, Poland to the west, and Lithuania and Latvia to the northwest. Its capital is Minsk; other major cities include Brest, Grodno , Gomel ,...

(the "Belarusian People’s Republic"), Ukraine

Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It has an area of 603,628 km², making it the second largest contiguous country on the European continent, after Russia...

(the "Hetmanate"), and Georgia

Georgia (country)

Georgia is a sovereign state in the Caucasus region of Eurasia. Located at the crossroads of Western Asia and Eastern Europe, it is bounded to the west by the Black Sea, to the north by Russia, to the southwest by Turkey, to the south by Armenia, and to the southeast by Azerbaijan. The capital of...

, Armenia

Armenia

Armenia , officially the Republic of Armenia , is a landlocked mountainous country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia...

, and Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan , officially the Republic of Azerbaijan is the largest country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia. Located at the crossroads of Western Asia and Eastern Europe, it is bounded by the Caspian Sea to the east, Russia to the north, Georgia to the northwest, Armenia to the west, and Iran to...

(the "Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic

Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic

The Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic , was a short-lived state composed of the modern-day countries of Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia in the South Caucasus.-...

"). Following the defeat of Germany in World War I, the Soviets eventually recovered the territories they gave up, with the exception of Finland, the Baltic States

Baltic states

The term Baltic states refers to the Baltic territories which gained independence from the Russian Empire in the wake of World War I: primarily the contiguous trio of Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania ; Finland also fell within the scope of the term after initially gaining independence in the 1920s.The...

, and Poland, which remained independent until the onset of World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

.

In the wake of the October Revolution

October Revolution

The October Revolution , also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution , Red October, the October Uprising or the Bolshevik Revolution, was a political revolution and a part of the Russian Revolution of 1917...

, the old Russian Imperial Army had been demobilized; the volunteer-based Red Guard was the Bolsheviks' main military force, augmented by an armed military component of the Cheka

Cheka

Cheka was the first of a succession of Soviet state security organizations. It was created by a decree issued on December 20, 1917, by Vladimir Lenin and subsequently led by aristocrat-turned-communist Felix Dzerzhinsky...

, the Bolshevik state security apparatus. In January, after significant reverses in combat, War Commissar Leon Trotsky headed the reorganization of the Red Guard into a Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, in order to create a more professional fighting force. Political commissars were appointed to each unit of the army to maintain morale and ensure loyalty.

In June 1918, when it became apparent that a revolutionary army composed solely of workers would be far too small, Trotsky instituted mandatory conscription of the rural peasantry into the Red Army. Opposition of rural Russians to Red Army conscription units was overcome by taking hostages and shooting them when necessary in order to force compliance, exactly the same practices used by the White Army officers too. Former Tsarist officers were utilized as "military specialists" (voenspetsy), sometimes taking their families hostage in order to ensure loyalty. At the start of the war, ¾ of the Red Army officer corps was composed of former Tsarist officers. By its end, 83% of all Red Army divisional and corps commanders were ex-Tsarist soldiers.

In the elections to the Constituent Assembly, the Bolsheviks constituted a minority of the vote and dissolved it. In general, they had support primarily in the Petrograd

Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg is a city and a federal subject of Russia located on the Neva River at the head of the Gulf of Finland on the Baltic Sea...

and Moscow

Moscow

Moscow is the capital, the most populous city, and the most populous federal subject of Russia. The city is a major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation centre of Russia and the continent...

Soviets and some other industrial regions.

While resistance to the Red Guard began on the very next day after the Bolshevik uprising, the Brest-Litovsk treaty and the political ban became a catalyst for the formation of anti-Bolshevik groups both inside and outside Russia, pushing them into action against the new regime.

A loose confederation of anti-Bolshevik forces aligned against the Communist government, including land-owners, republicans

Republicanism

Republicanism is the ideology of governing a nation as a republic, where the head of state is appointed by means other than heredity, often elections. The exact meaning of republicanism varies depending on the cultural and historical context...

, conservatives, middle-class citizens, reactionaries

Reactionary

The term reactionary refers to viewpoints that seek to return to a previous state in a society. The term is meant to describe one end of a political spectrum whose opposite pole is "radical". While it has not been generally considered a term of praise it has been adopted as a self-description by...

, pro-monarchists, liberals, army generals, non-Bolshevik socialists who still had grievances and democratic reformists, voluntarily united only in their opposition to Bolshevik rule. Their military forces, bolstered by forced conscriptions and terror and by foreign influence and led by General Yudenich, Admiral Kolchak and General Denikin, became known as the White movement

White movement

The White movement and its military arm the White Army - known as the White Guard or the Whites - was a loose confederation of Anti-Communist forces.The movement comprised one of the politico-military Russian forces who fought...

(sometimes referred to as the "White Army"), and they controlled significant parts of the former Russian empire for most of the war.

A Ukrainian

Ukrainians

Ukrainians are an East Slavic ethnic group native to Ukraine, which is the sixth-largest nation in Europe. The Constitution of Ukraine applies the term 'Ukrainians' to all its citizens...

nationalist movement known as the Green Army was active in Ukraine in the early part of the war. More significant was the emergence of an anarchist political and military movement known as the Revolutionary Insurrectionary Army of Ukraine

Revolutionary Insurrectionary Army of Ukraine

The Revolutionary Insurrectionary Army of Ukraine , popularly called Makhnovshchina, less correctly Makhnovchina, and also known as the Black Army, was an anarchist army formed largely of Ukrainian and Crimean peasants and workers under the command of the famous anarchist Nestor Makhno during the...

or the Anarchist Black Army

Revolutionary Insurrectionary Army of Ukraine

The Revolutionary Insurrectionary Army of Ukraine , popularly called Makhnovshchina, less correctly Makhnovchina, and also known as the Black Army, was an anarchist army formed largely of Ukrainian and Crimean peasants and workers under the command of the famous anarchist Nestor Makhno during the...

led by Nestor Makhno

Nestor Makhno

Nestor Ivanovych Makhno or simply Daddy Makhno was a Ukrainian anarcho-communist guerrilla leader turned army commander who led an independent anarchist army in Ukraine during the Russian Civil War....

. The Black Army, which counted numerous Jews and Ukrainian peasants in its ranks, played a key part in halting General Denikin's White Army offensive towards Moscow during 1919, later ejecting Cossack forces from the Crimea.

The Western Allies

Triple Entente

The Triple Entente was the name given to the alliance among Britain, France and Russia after the signing of the Anglo-Russian Entente in 1907....

also expressed their dismay at the Bolsheviks, (1) upset at the withdrawal of Russia from the war effort, (2) worried about a possible Russo-German alliance, and perhaps most importantly (3) galvanised by the prospect of the Bolsheviks making good their threats to assume no responsibility for, and so default on, Imperial Russia's massive foreign loans

External debt

External debt is that part of the total debt in a country that is owed to creditors outside the country. The debtors can be the government, corporations or private households. The debt includes money owed to private commercial banks, other governments, or international financial institutions such...

; the legal notion of odious debt

Odious debt

In international law, odious debt is a legal theory that holds that the national debt incurred by a regime for purposes that do not serve the best interests of the nation, should not be enforceable. Such debts are, thus, considered by this doctrine to be personal debts of the regime that incurred...

had not yet been formulated. In addition, there was a concern, shared by many Central Powers

Central Powers

The Central Powers were one of the two warring factions in World War I , composed of the German Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulgaria...

as well, that the socialist revolutionary ideas would spread to the West. Hence, many of these countries expressed their support for the Whites, including the provision of troops and supplies. Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, was a predominantly Conservative British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest wartime leaders of the century and served as Prime Minister twice...

declared that Bolshevism must be "strangled in its cradle".

The majority of the fighting ended in 1920 with the defeat of General Pyotr Wrangel in the Crimea

Crimea

Crimea , or the Autonomous Republic of Crimea , is a sub-national unit, an autonomous republic, of Ukraine. It is located on the northern coast of the Black Sea, occupying a peninsula of the same name...

, but a notable resistance in certain areas continued until 1923 (e.g. Kronstadt Uprising, Tambov Rebellion

Tambov Rebellion

The Tambov Rebellion which occurred between 1920 and 1921 was one of the largest and best-organized peasant rebellions challenging the Bolshevik regime during the Russian Civil War. The uprising took place in the territories of the modern Tambov Oblast and part of the Voronezh Oblast, less than...

, Basmachi Revolt

Basmachi Revolt

The Basmachi movement or Basmachi Revolt was an uprising against Russian Imperial and Soviet rule by the Muslim, largely Turkic peoples of Central Asia....

, and the final resistance of the White movement in the Far East

Russian Far East

Russian Far East is a term that refers to the Russian part of the Far East, i.e., extreme east parts of Russia, between Lake Baikal in Eastern Siberia and the Pacific Ocean...

).

Geography and chronology

In the European part of Russia, the war was fought across three main fronts: the eastern; the southern and the north-western. It can also be roughly split into the following periods.The first period lasted from the Revolution until the Armistice. Already on the date of the Revolution, Cossack

Cossack

Cossacks are a group of predominantly East Slavic people who originally were members of democratic, semi-military communities in what is today Ukraine and Southern Russia inhabiting sparsely populated areas and islands in the lower Dnieper and Don basins and who played an important role in the...

General Kaledin refused to recognize it and assumed full governmental authority in the Don region, where the Volunteer Army

Volunteer Army

The Volunteer Army was an anti-Bolshevik army in South Russia during the Russian Civil War of 1918-1920....

began amassing support. The signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was a peace treaty signed on March 3, 1918, mediated by South African Andrik Fuller, at Brest-Litovsk between Russia and the Central Powers, headed by Germany, marking Russia's exit from World War I.While the treaty was practically obsolete before the end of the year,...

also resulted in direct Allied intervention in Russia and the arming of military forces opposed to the Bolshevik government. There were also many German commanders who offered support against the Bolsheviks, fearing a confrontation with them was impending as well.

During this first period, the Bolsheviks took control of Central Asia

Central Asia

Central Asia is a core region of the Asian continent from the Caspian Sea in the west, China in the east, Afghanistan in the south, and Russia in the north...

out of the hands of the Provisional Government and White Army, setting up a base for the Communist Party in the Steppe and Turkestan, where nearly two million Russian settlers were located.

Most of the fighting in this first period was sporadic, involving only small groups amid a fluid and rapidly shifting strategic scene. Among the antagonists were the Czechoslovaks, known as the Czechoslovak Legion or "White Czechs", the Poles of the Polish 5th Rifle Division

Polish 5th Rifle Division

Polish 5th Siberian Rifle Division was a Polish military unit formed in 1919 in Russia during World War I. The division fought during the Polish-Bolshevik War, but as it was attached to the White Russian formations, it is considered to have fought more in the Russian Civil War...

and the pro-Bolshevik Red Latvian riflemen

Latvian Riflemen

This article is about Latvian military formations in World War I and Russian Civil War. For Red Army military formations in World War II see Latvian Riflemen Soviet Divisions....

.

The second period of the war lasted from January to November 1919. At first the White armies' advances from the south (under General Denikin), the east (under Admiral Kolchak) and the northwest (under General Yudenich

Nikolai Nikolaevich Yudenich

Nikolai Nikolaevich Yudenich , was a commander of the Russian Imperial Army during World War I. He was a leader of the anti-communist White movement in Northwestern Russia during the Civil War.-Early life:...

) were successful, forcing the Red Army and its leftist allies back on all three fronts. In July 1919, the Red Army suffered another reverse after a mass defection of Red Army units in the Crimea to the anarchist Black Army under Nestor Makhno

Nestor Makhno

Nestor Ivanovych Makhno or simply Daddy Makhno was a Ukrainian anarcho-communist guerrilla leader turned army commander who led an independent anarchist army in Ukraine during the Russian Civil War....

, enabling anarchist forces to consolidate power in Ukraine.

Leon Trotsky soon reformed the Red Army, concluding the first of two military alliances with the anarchists. In June, the Red Army first checked Kolchak's advance. After a series of engagements, assisted by a Black Army offensive against White supply lines, the Red Army defeated Denikin's and Yudenich's armies in October and November.

The third period of the war was the extended siege of the last White forces in the Crimea

Crimea

Crimea , or the Autonomous Republic of Crimea , is a sub-national unit, an autonomous republic, of Ukraine. It is located on the northern coast of the Black Sea, occupying a peninsula of the same name...

. Wrangel

Pyotr Nikolayevich Wrangel

Baron Pyotr Nikolayevich Wrangel or Vrangel was an officer in the Imperial Russian army and later commanding general of the anti-Bolshevik White Army in Southern Russia in the later stages of the Russian Civil War.-Life:Wrangel was born in Mukuliai, Kovno Governorate in the Russian Empire...

had gathered the remnants of the Denikin's armies, occupying much of the Crimea. An attempted invasion of southern Ukraine was rebuffed by the anarchist Black Army under the command of Nestor Makhno. Pursued into the Crimea by Makhno's troops, Wrangel went over to the defensive in the Crimea. After an abortive move north against the Red Army, Wrangel's troops were forced south by Red Army and Black Army forces; Wrangel and the remains of his army were evacuated to Constantinople

Constantinople

Constantinople was the capital of the Roman, Eastern Roman, Byzantine, Latin, and Ottoman Empires. Throughout most of the Middle Ages, Constantinople was Europe's largest and wealthiest city.-Names:...

in November 1920.