Polish-Soviet War

Encyclopedia

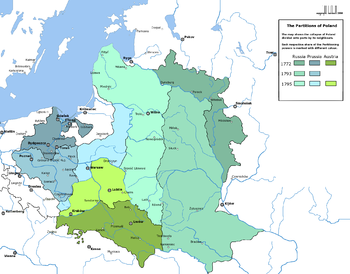

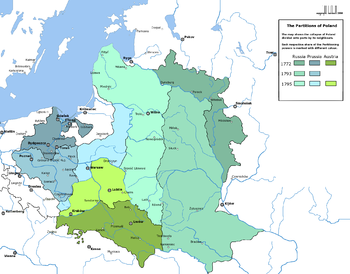

The Polish–Soviet War (February 1919 – March 1921) was an armed conflict between Soviet Russia and Soviet Ukraine and the Second Polish Republic

and the Ukrainian People's Republic

—four states in post–World War I Europe. Poland, whose statehood had just been re-established by the Treaty of Versailles

following the Partitions of Poland

in the late 18th century, sought to secure territories it had lost at the time of partitions; the Soviet states aimed to control those same territories, which had been part of the Russian Empire

until the turbulent events of World War I. On the Soviet part, the ideological factor was also important, as the newly created communist state sought to spread its revolution to Central

, and later Western Europe

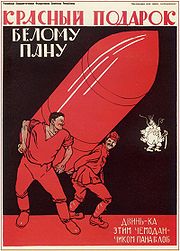

. This is evident by Marshal Tukhachevsky's daily order to his troops: "Over the corpse of Poland leads the road to the world's fire. Towards Wilno, Minsk, Warsaw go!" Despite the final retreat of Russian forces and annihilation of their three field armies, historians don't universally agree on the question of victory.Russian and Polish historians tend to assign victory to their respective countries. Outside assessments vary, mostly between calling the result a Polish victory and inconclusive. Lenin, in his secret report to the 9th Conference of the Bolshevik Party on , called the outcome of the war, "In a word, a gigantic, unheard-of defeat." (See ) The Poles claimed a successful defense of their state, while the Soviets claimed a repulse of the Polish eastward invasion of Ukraine and Belarus, which they viewed as a part of the foreign intervention in the Russian Civil War

.

The Treaty of Versailles

had only vaguely defined the frontiers between Poland and Bolshevik Russia, and post-war events created turmoil—the Russian Revolution of 1917

, the crumbling of the Russian

, German

and Austrian

empires, the Russian Civil War

, the Central Powers

' withdrawal from the eastern front

, and the attempts of Ukraine

and Belarus

to establish independence. Poland's Chief of State, Józef Piłsudski, felt the time was right to expand Polish borders as far east as feasible, to be followed by a Polish-led Intermarum

federation of East-Central-European states as a bulwark against the re-emergence of German and Russian imperialism

s. Lenin

, meanwhile, saw Poland as the bridge the Red Army

had to cross to assist other communist movements

and bring about other European revolutions.

By 1919, Polish forces had taken control of much of Western Ukraine

, emerging victorious from the Polish–Ukrainian War. The West Ukrainian People's Republic, led by Yevhen Petrushevych

, had tried unsuccessfully to create a Ukrainian state on territories to which both Poles and Ukrainians laid claim. At the same time in the Russian part of Ukraine Symon Petliura tried to defend and strengthen the Ukrainian People's Republic

, but as the Bolsheviks began to gain the upper hand in the Russian Civil War, they started to advance westward towards the disputed Ukrainian territories causing Petliura's forces to retreat to Podolia

. By the end of 1919 a clear front had formed as Petliura decided to ally with Piłsudski. Border skirmishes escalated into open warfare following Piłsudski's major incursion further east into Ukraine in April 1920. The Polish offensive was met by an initially successful Red Army counterattack

. The Soviet operation threw the Polish forces back westward all the way to the Polish capital, Warsaw

, while the Directorate of Ukraine

fled to Western Europe. Meanwhile, Western fears of Soviet troops arriving at the German frontiers increased the interest of Western powers

in the war. In midsummer, the fall of Warsaw seemed certain but in mid-August the tide had turned again as the Polish forces achieved an unexpected and decisive victory at the Battle of Warsaw

. In the wake of the Polish advance eastward, the Soviets sued for peace and the war ended with a ceasefire

in October 1920. A formal peace treaty

, the Peace of Riga

, was signed on 18 March 1921, dividing the disputed territories between Poland and Soviet Russia. The war largely determined the Soviet–Polish border for the period between the World Wars. Much of the territory ceded to Poland in the Treaty of Riga became part of the Soviet Union after World War II, when Poland's eastern borders were redefined by the Allies

in close accordance with the British-drawn Curzon Line

of 1920.

”) did not officially exist until . Alternative names include “Russo–Polish War [or Polish–Russian War] of 1919–1921”See for instance Russo-Polish War in Encyclopædia Britannica

“The conflict began when the Polish head of state Józef Piłsudski formed an alliance with the Ukrainian nationalist leader Symon Petlyura and their combined forces began to overrun Ukraine, occupying Kiev on 7 May.” (to distinguish it from earlier Polish–Russian wars) and “Polish–Bolshevik War”. This second term (or just “Bolshevik War” ) is most common in Polish sources. In some Polish sources it is also referred as the "War of 1920" (Polish: Wojna 1920 roku).For example: 1) Sąsiedzi wobec wojny 1920 roku. Wybór dokumentów.

2) Wojna 1920 roku na Mazowszu i Podlasiu

3) Nad Wisłą i Wkrą. Studium do polsko–radzieckiej wojny 1920 roku

Other points of contention are the starting and ending dates of the war. For example, Encyclopædia Britannica

begins its article with the date (1919–1920), but then states "Although there had been hostilities between the two countries during 1919, the conflict began when the Polish head of state Józef Pilsudski formed an alliance with the Ukrainian nationalist leader Symon Petlyura (21 April 1920) and their combined forces began to overrun Ukraine, occupying Kiev on 7 May." while the Polish Internetowa encyklopedia PWN as well as some Western historians—like Norman Davies

—consider 1919 as the starting year of the war. The ending date is given as either 1920 or 1921; this confusion stems from the fact that while the ceasefire

was put in force in the autumn of 1920, the official treaty ending the war was signed months later, in March 1921.

While the events of 1919 can be described as a border conflict—and only in early 1920 did both sides realize they were engaged in all-out war—the conflicts that took place in 1920 were an inevitable escalation of fighting that began in earnest a year earlier. In the end, the events of 1920 were a logical, though unforeseen, consequence of the 1919 prelude.

The war's main area of contention is in present-day Ukraine and Belarus and was, until the middle of the 14th century, part of the medieval state of Kievan Rus'

The war's main area of contention is in present-day Ukraine and Belarus and was, until the middle of the 14th century, part of the medieval state of Kievan Rus'

. After a period of internecine wars and the Mongolian invasion of 1240, they became objects of expansion for Poland and Lithuania. In the first half of the 14th century, Kiev and land between the Dnieper, Pripyat

, and Dvina rivers became part of Lithuania, and in 1352 the Galicia-Volyn principality was split between Poland and Lithuania. In 1569, according to the Union of Lublin

between Poland and Lithuania, some of the Ukrainian lands passed to the Polish crown. Between 1772–1795, much of the Eastern Slavic territories became part of Russia. After the Congress of Vienna

in 1814–1815, much of the territory of the Duchy of Warsaw

(Poland) was transferred to Russian control.

In the aftermath of World War I

, the map of Central

and Eastern Europe

had drastically changed. Germany's defeat rendered its plans for the creation of Eastern European puppet state

s (Mitteleuropa

) obsolete, and the Russian Empire collapsed, resulting in a revolution

and a civil war

. Many small nations of the region saw a chance for real independence and seized the opportunity to gain it; Russia viewed these territories as rebellious provinces, vital for its security, but was unable to react swiftly. While the Paris Peace Conference

had not made a definitive ruling in regard to the Poland's eastern border, it issued a provisional boundary in December 1919 – the Curzon line

– as an attempt to define the territories that had an "indisputably Polish ethnic majority"; the participants did not feel competent to make a certain judgement on the competing claims.

With the success of the Greater Poland Uprising in 1918

, Poland had re-established its statehood

for the first time since the 1795 partition. Formed as the Second Polish Republic

, it proceeded to carve out its borders from the territories of its former partitioners. These territories had long been the object of conflict between Russia and Poland.

Poland was not alone in its newfound opportunities and troubles. With the collapse of Russian and German occupying authorities

Poland was not alone in its newfound opportunities and troubles. With the collapse of Russian and German occupying authorities

, virtually all of the newly independent neighbours began fighting over borders: Romania

fought with Hungary over Transylvania

, Yugoslavia

with Italy over Rijeka

, Poland with Czechoslovakia

over Cieszyn Silesia

, with Germany over Poznań

and with Ukrainians over Eastern Galicia. Ukrainians

, Belarusians, Lithuanians, Estonians and Latvians fought against each other and against the Russians, who were just as divided. Spreading Communist influences resulted in Communist revolutions in Munich

, Berlin, Budapest

and Prešov

. Winston Churchill

commented: "The war of giants has ended, the wars of the pygmies began." All of these engagements–with the sole exception of the Polish–Soviet war–would be short-lived.

The Polish–Soviet war likely happened more by accident than design, as it is unlikely that anyone in Soviet Russia or in the new Second Republic of Poland would have deliberately planned a major foreign war. Poland, its territory a major frontline of the First World War, was unstable politically; it had just won the difficult conflict with the West Ukrainian National Republic and was already engaged in new conflicts with Germany (the Silesian Uprisings

) and with Czechoslovakia

. The attention of revolutionary Russia, meanwhile, was predominantly directed at thwarting counter-revolution and intervention by the Western powers

. While the first clashes between Polish and Soviet forces occurred in February 1919, it would be almost a year before both sides realised that they were engaged in a full war.

The Soviet Government denied charges of trying to invade Europe.

The Soviet Government denied charges of trying to invade Europe.

Polish leader Pilsudski said:

Some authors believe that as early as late 1919 the leader of Russia's new Communist government, Vladimir Lenin

, was inspired by the Red Army's civil-war victories over White Russian

anti-communist forces and their Western allies, and began to see the future of the revolution with greater optimism. The Bolsheviks proclaimed the need for the dictatorship of the proletariat

, and agitated for a worldwide Communist community. Their avowed intent was to link the revolution in Russia with an expected revolution in Germany

and to assist other Communist movements in Western Europe

; Poland was the geographical bridge that the Red Army

would have to cross to do so. Lenin aimed to regain control of the territories ceded by Russia in the Brest-Litovsk Treaty, to infiltrate the borderlands, set up Soviet governments there as well as in Poland, and reach Germany where he expected a Socialist revolution to break out. He believed that Soviet Russia could not survive without the support of a socialist Germany. By the end of summer 1919 the Soviets managed to take over most of Ukraine, driving the Ukrainian Directorate

from Kiev. In early 1919, they also set up a Lithuanian-Belorussian Republic (Litbel). This government was very unpopular due to terror and the collection of food and goods for the army.

As the war progressed, particularly around the time the Polish Kiev Offensive of 1920 had been repelled, the Soviet leaders, including Lenin, increasingly saw the war as the real opportunity to spread the revolution westwards. Historian Richard Pipes

noted that before the Kiev Offensive, Soviets had been preparing their own strike against Poland.

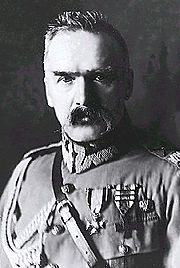

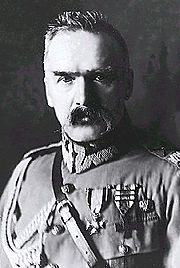

Before the start of the Polish–Soviet War, Polish politics were strongly influenced by Chief of State (naczelnik państwa

Before the start of the Polish–Soviet War, Polish politics were strongly influenced by Chief of State (naczelnik państwa

) Józef Piłsudski. Piłsudski wanted to break up the Russian Empire

and create a Polish-led "Międzymorze

Federation" of independent states: Poland, Lithuania

, Ukraine

, and other Central and East European countries emerging out of crumbling empires after the First World War. This new union became a counterweight to any potential imperialist

intentions on the part of Russia or Germany. Piłsudski argued that "There can be no independent Poland without an independent Ukraine", but he may have been more interested in Ukraine being split from Russia than in Ukrainians' welfare. He did not hesitate to use military force to expand the Polish borders to Galicia and Volhynia

, crushing a Ukrainian attempt at self-determination in the disputed territories east of the Southern Bug

River, which contained a significant Polish minority, forming majority in cities like Lwów, but a Ukrainian majority in the countryside. Speaking of Poland's future frontiers, Piłsudski said: "All that we can gain in the west depends on the Entente

—on the extent to which it may wish to squeeze Germany," while in the east, "There are doors that open and close, and it depends on who forces them open and how far." In the chaos to the east the Polish forces set out to expand there as much as it was feasible. On the other hand, Poland had no intention of joining the Western intervention in the Russian Civil War or of conquering Russia itself.

Before the Polish–Soviet war, Jan Kowalewski

, a polyglot

and amateur cryptologist, managed to break the codes and ciphers of the army of the West Ukrainian People's Republic and General Anton Denikin's White Russian

forces during his service in the Polish–Ukrainian War. As a result, in July 1919 he was transferred to Warsaw

, where he became chief of the Polish General Staff

's radio-intelligence department. By early September he had gathered a group of mathematicians from Warsaw University and Lwów University (most notably, founders of the Polish School of Mathematics

—Stanisław Leśniewski, Stefan Mazurkiewicz

and Wacław Sierpiński), who were also able to break Russian ciphers. Decoded information presented to Pilsudski showed that Soviet peace proposals with Poland in 1919 were false and in reality they had prepared for a new offensive against Poland and concentrated military forces in Barysaw near the Polish border. Pilsudski decided to ignore Soviet proposals, sign an alliance with Symon Petliura and prepared the Kiev Offensive. During the war, decryption of Red Army radio messages made it possible to use small Polish military forces efficiently against the Russians and win many individual battles, the most important being the 1920 Battle of Warsaw

.

of the war took place around 14 February – 16 February, near the towns of Maniewicze and Biaroza

in Belarus. By late February the Soviet westward advance had come to a halt. Both Polish and Soviet forces had also been engaging the Ukrainian forces, and active fighting was going on in the territories of the Baltic countries (cf. Estonian War of Independence, Latvian War of Independence, Lithuanian Wars of Independence).

In early March 1919, Polish units started an offensive, crossing the Neman River

In early March 1919, Polish units started an offensive, crossing the Neman River

, taking Pinsk

, and reaching the outskirts of Lida

. Both the Soviet and Polish advances began around the same time in April (Polish forces started a major offensive on 16 April), resulting in increasing numbers of troops arriving in the area. That month the Red Army

had captured Grodno, but was soon pushed out by a Polish counter-offensive. Unable to accomplish its objectives and facing strengthening offensives from the White forces, the Red Army withdrew from its positions and reorganized. Soon the Polish–Soviet War would begin in earnest.

Polish forces continued a steady eastern advance. They took Lida

on 17 April and Nowogródek on 18 April, and recaptured Vilnius

on 19 April, driving the Litbel government from their proclaimed capital. On 8 August, Polish forces took Minsk

and on the 28th of that month they deployed tank

s for the first time. After heavy fighting, the town of Babruysk

near the Berezina River

was captured. By 2 October, Polish forces reached the Daugava river and secured the region from Desna to Daugavpils

(Dyneburg).

Polish success continued until early 1920. Sporadic battles erupted between Polish forces and the Red Army, but the latter was preoccupied with the White counter-revolutionary forces

Polish success continued until early 1920. Sporadic battles erupted between Polish forces and the Red Army, but the latter was preoccupied with the White counter-revolutionary forces

and was steadily retreating on the entire western frontline, from Latvia

in the north to Ukraine in the south. In early summer 1919, the White movement had gained the initiative, and its forces under the command of Anton Denikin were marching on Moscow. Piłsudski was aware that the Soviets were not friends of independent Poland, and considered war with Soviet Russia inevitable. He viewed their westward advance as a major issue, but also thought that he could get a better deal for Poland from the Bolshevik

s than their Russian civil war contenders, as the White Russians

– representatives of the old Russian Empire

, partitioner of Poland

– were willing to accept only limited independence of Poland, likely in the borders similar to that of Congress Poland

, and clearly objected to Ukrainian independence, crucial for Piłsudski's Międzymorze

, while the Bolsheviks did proclaim the partitions null and void. Piłsudski thus speculated that Poland would be better off with the Bolsheviks, alienated from the Western powers, than with the restored Russian Empire. By his refusal to join the attack on Lenin's struggling government, ignoring the strong pressure from the Entente

, Piłsudski had possibly saved the Bolshevik government in summer–fall 1919, although a full scale attack by the Poles in support of Denikin was practically not possible. He later wrote that in case of a White victory, in the east Poland could only gain the "ethnic border" at best (the Curzon line

). At the same time, Lenin offered Poles the territories of Minsk

, Zhytomyr

, Khmelnytskyi

, in what was described as mini "Brest

"; Polish military leader Kazimierz Sosnkowski

wrote that the territorial proposals of the Bolsheviks were much better than what the Poles had wanted to achieve.

In 1919, several unsuccessful attempts at peace negotiations were made by various Polish and Russian factions. In the meantime, Polish–Lithuanian relations worsened as Polish politicians found it hard to accept the Lithuanians' demands for certain territories, especially the city of Vilnius

In 1919, several unsuccessful attempts at peace negotiations were made by various Polish and Russian factions. In the meantime, Polish–Lithuanian relations worsened as Polish politicians found it hard to accept the Lithuanians' demands for certain territories, especially the city of Vilnius

which had a Polish ethnic majority but was regarded by Lithuanians as their historical capital. Polish negotiators made better progress with the Latvia

n Provisional Government, and in late 1919 and early 1920 Polish and Latvian forces were conducting joint operations including the Battle of Daugavpils

, against Soviet Russia.

The Warsaw Treaty

, an agreement with the exiled Ukrainian nationalist leader Symon Petlura

signed on 21 April 1920, was the main Polish diplomatic success. Petlura, who formally represented the government of the Ukrainian People's Republic

(by then de facto defeated by Bolsheviks), along with some Ukrainian forces, fled to Poland, where he found asylum. His control extended only to a sliver of land near the Polish border. In such conditions, there was little difficulty convincing Petlura to join an alliance with Poland, despite recent conflict between the two nations that had been settled in favour of Poland. By concluding an agreement with Piłsudski, Petlura accepted the Polish territorial gains in Western Ukraine and the future Polish–Ukrainian border along the Zbruch River

. In exchange, he was promised independence for Ukraine and Polish military assistance in reinstalling his government in Kiev.

For Piłsudski, this alliance gave his campaign for the Międzymorze federation the legitimacy of joint international effort, secured part of the Polish eastward border, and laid a foundation for a Polish-dominated Ukrainian state between Russia and Poland. For Petlura, this was the final chance to preserve the statehood and, at least, the theoretical independence of the Ukrainian heartlands, even while accepting the loss of West Ukrainian lands to Poland. Yet both of them were opposed at home. Piłsudski faced stiff opposition from Dmowski's National Democrats who opposed Ukrainian independence. Petlura, in turn, was criticized by many Ukrainian politicians for entering a pact with the Poles and giving up on Western Ukraine.

The alliance with Petlura did result in 15,000 pro-Polish allied Ukrainian troops at the beginning of the campaign, increasing to 35,000 through recruitment and desertion from the Soviet side during the war. This would, in the end, provide insufficient support for the alliance's aspirations.

Norman Davies

Norman Davies

notes that estimating strength of the opposing sides is difficult – even generals often had incomplete reports of their own forces.

By early 1920, the Red Army had been very successful against the White armies

. They defeated Denikin and signed peace treaties with Latvia and Estonia. The Polish front became their most important war theater and a plurality of Soviet resources and forces were diverted to it. In January 1920, the Red Army began concentrating a 700,000-strong force near the Berezina River

and on Belarus.

By the time Poles launched their Kiev offensive, the Red Southwestern Front had about 82,847 soldiers including 28,568 front-line troops. The Poles had some numerical superiority, estimated from 12,000 to 52,000 personnel. By the time of the Soviet counter-offensive in mid 1920 the situation had been reversed: the Soviets numbered about 790,000 – at least 50,000 more than the Poles; Tukhachevsky

estimated that he had 160,000 "combat ready" soldiers; Piłsudski estimated his enemy's forces at 200,000–220,000.

In the course of 1920, almost 800,000 Red Army personnel were sent to fight in the Polish war, of whom 402,000 went to the Western front and 355,000 to the armies of the South-West front in Galicia. Grigoriy Krivosheev

gives similar numbers, with 382,000 personnel for the Western Front and 283,000 personnel for the Southwestern Front.

Norman Davies

shows the growth of Red Army forces on the Polish front in early 1920:

Among the commanders leading the Red Army in the coming offensive were Leon Trotsky

, Tukhachevsky (new commander of the Western Front), Alexander Yegorov (new commander of the Southwestern Front), the future Soviet ruler Joseph Stalin

, and the founder of the Cheka

(secret police), Felix Dzerzhinsky

.

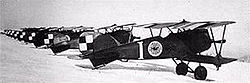

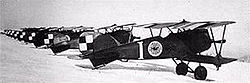

The Polish Army was made up of soldiers who had formerly served in the various partitioning empires, supported by some international volunteers, such as the Kościuszko Squadron. Boris Savinkov

was at the head of an army of 20,000 to 30,000 largely Russian POWs, and was accompanied by Dmitry Merezhkovsky

and Zinaida Gippius

. The Polish forces grew from approximately 100,000 in 1918 to over 500,000 in early 1920. In August, 1920, the Polish army had reached a total strength of 737,767 people; half of that was on the frontline. Given Soviet losses, there was rough numerical parity between the two armies; and by the time of the battle of Warsaw

Poles might have even had a slight advantage in numbers and logistics.

Logistics

, nonetheless, were very bad for both armies, supported by whatever equipment was left over from World War I or could be captured. The Polish Army, for example, employed guns made in five countries, and rifle

s manufactured in six, each using different ammunition. The Soviets had many military depots at their disposal, left by withdrawing German armies in 1918–19, and modern French armaments captured in great numbers from the White Russians and the Allied expeditionary forces in the Russian Civil War. Still, they suffered a shortage of arms; both the Red Army and the Polish forces were grossly underequipped by Western standards.

The Soviet High Command planned a new offensive in late April/May. Since March 1919, Polish intelligence was aware that the Soviets had prepared for a new offensive and the Polish High Command decided to launch their own offensive before their opponents. The plan for Operation Kiev was to beat the Red Army on Poland's southern flank and install a Polish-friendly Petlura government in Ukraine.

Until April, the Polish forces had been slowly but steadily advancing eastward. The new Latvia

Until April, the Polish forces had been slowly but steadily advancing eastward. The new Latvia

n government requested and obtained Polish help in capturing Daugavpils

. The city fell after heavy fighting at the Battle of Daugavpils

in January and was handed over to the Latvians. By March, Polish forces had driven a wedge between Soviet forces to the north (Belorussia) and south (Ukraine).

On 24 April, Poland began its main offensive, Operation Kiev. Its stated goal was the creation of an independent Ukraine that would become part of Piłsudski's project of a "Międzymorze

" Federation. Poland's forces were assisted by 15,000 Ukrainian soldiers under Symon Petlura

, representing the Ukrainian People's Republic

.

On 26 April, in his "Call to the People of Ukraine", Piłsudski told his audience that "the Polish army would only stay as long as necessary until a legal Ukrainian government took control over its own territory". Despite this, many Ukrainians were just as anti-Polish as anti-Bolshevik, and resented the Polish advance.

The Polish 3rd Army easily won border clashes with the Red Army in Ukraine but the Reds withdrew with minimal losses. Subsequently, the combined Polish–Ukrainian forces entered an abandoned Kiev

on 7 May, encountering only token resistance.

This Polish military thrust was met with Red Army

counterattack

s on 29 May. Polish forces in the area, preparing for an offensive towards Zhlobin

, managed to hold their ground, but were unable to start their own planned offensive. In the north, Polish forces had fared much worse. The Polish 1st Army was defeated and forced to retreat, pursued by the Russian 15th Army, which recaptured territories between the Western Dvina and Berezina rivers. Polish forces attempted to take advantage of the exposed flanks of the attackers but the enveloping forces failed to stop the Soviet advance. At the end of May, the front had stabilised near the small river Auta, and Soviet forces began preparing for the next push.

On 24 May 1920, the Polish forces in the south were engaged for the first time by Semyon Budyonny's famous 1st Cavalry Army

(Konarmia). Repeated attacks by Budyonny's Cossack

cavalry broke the Polish–Ukrainian front on 5 June. The Soviets then deployed mobile cavalry units to disrupt the Polish rearguard, targeting communications and logistics. By 10 June, Polish armies were in retreat along the entire front. On 13 June, the Polish army, along with the Petlura's Ukrainian troops, abandoned Kiev to the Red Army.

On 30 May 1920 General Aleksei Brusilov

On 30 May 1920 General Aleksei Brusilov

published in Pravda

an appeal entitled “To All Former Officers, Wherever They Might Be”, encouraging them to forgive past grievances and to join the Red Army

. Brusilov considered it as a patriotic duty of all Russian officers to join hands with the Bolshevik government, that in his opinion was defending Russia against foreign invaders. Lenin also spotted the use of Russian patriotism. Thus, the Central Committee appealed to the „respected citizens of Russia“ to defend the Soviet republic against a Polish usurpation. The historians recalled the Polish invasions of the early 17th century.

Russia's counter-offensive was indeed boosted by Brusilov's engagement; 14,000 officers and over 100,000 deserters enlisted in or returned to the Red Army, and thousands of civilian volunteers contributed to the effort. The commander of the Polish 3rd Army in Ukraine, General Edward Rydz-Śmigły, decided to break through the Soviet line toward the northwest. Polish forces in Ukraine managed to withdraw relatively unscathed, but were unable to support the northern front and reinforce the defenses at the Auta River for the decisive battle that was soon to take place there.

Due to insufficient forces, Poland's 200-mile-long front was manned by a thin line of 120,000 troops backed by some 460 artillery pieces with no strategic reserves. This approach to holding ground harked back to the World War I practice of "establishing a fortified line of defense". It had shown some merit on the Western Front saturated with troops, machine guns, and artillery. Poland's eastern front, however, was weakly manned, supported with inadequate artillery, and had almost no fortifications.

Against the Polish line the Red Army gathered its Northwest Front led by the young General Mikhail Tukhachevsky

. Their numbers exceeded 108,000 infantry and 11,000 cavalry, supported by 722 artillery pieces and 2,913 machine guns. The Soviets at some crucial places outnumbered the Poles four-to-one.

Tukhachevsky launched his offensive on 4 July, along the Smolensk

–Brest-Litovsk axis, crossing the Auta and Berezina rivers. The northern 3rd Cavalry Corps, led by Gayk Bzhishkyan

(Gay Dmitrievich Gay, Gaj-Chan), were to envelop Polish forces from the north, moving near the Lithuanian and Prussian border (both of these belonging to nations hostile to Poland). The 4th, 15th, and 3rd Armies were to push west, supported from the south by the 16th Army

and Mozyr Group. For three days the outcome of the battle hung in the balance, but the Soviet' numerical superiority proved decisive and by 7 July Polish forces were in full retreat along the entire front. However, due to the stubborn defense by Polish units, Tukhachevsky's plan to break through the front and push the defenders southwest into the Pinsk Marshes

failed.

Polish resistance was offered again on a line of "German trenches", a line of heavy World War I field fortifications that presented an opportunity to stem the Red Army offensive. However, the Polish troops were insufficient in number. Soviet forces found a weakly defended part of the front and broke through. Gej-Chan and Lithuanian forces captured Vilnius on 14 July, forcing the Poles into retreat again. In Galicia to the south, General Semyon Budyonny

's cavalry advanced far into the Polish rear, capturing Brodno

and approaching Lwów

and Zamość

. In early July, it became clear to the Poles that the Soviets' objectives were not limited to pushing their borders westwards. Poland's very independence was at stake.

Soviet forces moved forward at the remarkable rate of 20 miles (32.2 km) a day. Grodno in Belarus fell on 19 July; Brest-Litovsk fell on 1 August. The Polish attempted to defend the Bug River

line with 4th Army and Grupa Poleska units, but were able to delay the Red Army advance for only one week. After crossing the Narew River on 2 August, the Soviet Northwest Front was only 60 miles (96.6 km) from Warsaw. The Brest-Litovsk fortress, which became the headquarters of the planned Polish counteroffensive, fell to the 16th Army in the first attack. The Soviet Southwest Front pushed the Polish forces out of Ukraine. Stalin had then disobeyed his orders and ordered his forces to close on Zamość, as well as Lwów – the largest city in southeastern Poland and an important industrial center, garrisoned by the Polish 6th Army. The city was soon besieged

. This created a hole in the lines of the Red Army, but at the same time opened the way to the Polish capital. Five Soviet armies approached Warsaw.

Polish forces in Galicia near Lwów launched a successful counteroffensive to slow down the Red Army advance. This stopped the retreat of Polish forces on the southern front. However, the worsening situation near the Polish capital of Warsaw prevented the Poles from continuing that southern counteroffensive and pushing east. Forces were mustered to take part in the coming battle for Warsaw

.

's, rose. Piłsudski did manage to regain his influence, especially over the military, almost at the last moment—as the Soviet forces were approaching Warsaw. The Polish political scene had begun to unravel in panic, with the government of Leopold Skulski

resigning in early June.

Meanwhile, the Soviet leadership's confidence soared. In a telegram, Lenin exclaimed: "We must direct all our attention to preparing and strengthening the Western Front. A new slogan must be announced: 'Prepare for war against Poland'." Soviet communist theorist Nikolay Bukharin, writer for the newspaper Pravda

, wished for the resources to carry the campaign beyond Warsaw "right up to London and Paris". General Tukhachevsky's order of the day, 2 July 1920 read: "To the West! Over the corpse of White Poland lies the road to worldwide conflagration. March on Vilno

, Minsk

, Warsaw

!" and "onward to Berlin

over the corpse of Poland!" The increasing hope of certain victory, however, gave rise to political intrigues between Soviet commanders.

By order of the Soviet Communist Party, a Polish puppet government, the Provisional Polish Revolutionary Committee

(Polish: Tymczasowy Komitet Rewolucyjny Polski, TKRP), had been formed on 28 July in Białystok to organise administration of the Polish territories captured by the Red Army. The TKRP had very little support from the ethnic Polish population and recruited its supporters mostly from the ranks of minorities, primarily Jews

. At the height of the Polish–Soviet conflict, Jews had been subject to anti-semitic violence by Polish forces, who considered Jews a potential threat, and who often accused Jews as being the masterminds of Russian Bolshevism; during the Battle of Warsaw, the Polish government interned all Jewish volunteers and sent Jewish volunteer officers to an internment camp.

Britain's Prime Minister, David Lloyd George

Britain's Prime Minister, David Lloyd George

, who wanted to negotiate a favourable trade agreement with the Bolsheviks pressed Poland to make peace on Soviet terms and refused any assistance to Poland that would alienate the Whites in the Russian Civil War. In July 1920, Britain announced it would send huge quantities of World War I surplus military supplies to Poland, but a threatened general strike by the Trades Union Congress

, who objected to British support of "White Poland", ensured that none of the weapons destined for Poland left British ports. David Lloyd George had never been enthusiastic about supporting the Poles, and had been pressured by his more right-wing Cabinet members such as Lord Curzon and Winston Churchill

into offering the supplies.

In early July 1920, Prime Minister Władysław Grabski travelled to the Spa Conference

in Belgium to request assistance. The Allied representatives were largely unsympathetic. Grabski signed an agreement containing several terms: that Polish forces withdraw to the Curzon Line

, which the Allies had published in December 1919, delineating Poland's ethnographic frontier; that it participate in a subsequent peace conference; and that the questions of sovereignty over Vilnius, Eastern Galicia, Cieszyn Silesia

, and Danzig be remanded to the Allies. Ambiguous promises of Allied support were made in exchange.

On 11 July 1920, the government of Great Britain sent a telegram to the Soviets, signed by Curzon, which has been described as a de facto ultimatum

. It requested that the Soviets halt their offensive at the Curzon line and accept it as a temporary border with Poland, until a permanent border could be established in negotiations. In case of Soviet refusal, the British threatened to assist Poland with all the means available, which, in reality, were limited by the internal political situation in the United Kingdom. On the 17 July, the Bolsheviks refused and made a counter-offer to negotiate a peace treaty directly with Poland. The British responded by threatening to cut off the on-going trade negotiations if the Soviets conducted further offensives against Poland. These threats were ignored.

On 6 August 1920, the British Labour Party

published a pamphlet stating that British workers would never take part in the war as Poland's allies, and labour unions blocked supplies to the British expeditionary force assisting Russian Whites in Arkhangelsk

. French Socialists, in their newspaper L'Humanité

, declared: "Not a man, not a sou

, not a shell for reactionary and capitalist Poland. Long live the Russian Revolution! Long live the Workmen's International!" Poland also suffered setbacks due to sabotage and delays in deliveries of war supplies, when workers in Czechoslovakia and Germany refused to transit such materials to Poland. On 6 August the Polish government issued an "Appeal to the World", disputing charges of imperialism

, stressing Poland's determination for self-determination

and the dangers of Bolshevik "invasion of Europe".

Poland's neighbor Lithuania

had been engaged in serious disputes with Poland over the city of Vilnius

and the borderlands surrounding Sejny

and Suwałki. A 1919 Polish attempt to take control over the entire nation by a coup had additionally disrupted their relationship. The Soviet and Lithuanian governments signed the Soviet-Lithuanian Treaty of 1920 on 12 July; this treaty recognized Vilnius as part of Lithuania. The treaty contained a secret clause allowing Soviet forces unrestricted movement within Soviet-recognized Lithuanian territory during any Soviet war with Poland; this clause would lead to questions regarding the issue of Lithuanian neutrality

in the ongoing Polish–Soviet War. The Lithuanians also provided the Soviets with logistical support. Despite Lithuanian support, the Soviets did not transfer Vilnius to the Lithuanians till just before the city was recaptured by the Polish forces (in late August), instead up till that time the Soviets encouraged their own, pro-communist Lithuanian government, Litbel, and were planning a pro-communist coup in Lithuania. The simmering conflict between Poland and Lithuania culminated in the Polish–Lithuanian War

in August 1920.

Polish allies were few. France, continuing its policy of countering Bolshevism now that the Whites in Russia proper had been almost completely defeated, sent a 400-strong advisory group to Poland's aid

in 1919. It consisted mostly of French officers, although it also included a few British advisers

led by Lieutenant General Sir Adrian Carton De Wiart

. The French officers included a future President of France, Charles de Gaulle

; during the war he won Poland's highest military decoration, the Virtuti Militari

. In addition to the Allied advisors, France also facilitated the transit to Poland from France of the "Blue Army" in 1919: troops mostly of Polish origin, plus some international volunteers, formerly under French command in World War I. The army was commanded by the Polish general, Józef Haller. Hungary offered to send a 30,000 cavalry corps to Poland's aid, but the Czechoslovakian government refused to allow them through, as there was a demilitarized zone on the borders after the Czech-Hungarian war that had ended only a few months before. Some trains with weapon supplies from Hungary did, however, arrive in Poland.

In mid-1920, the Allied Mission was expanded by some advisers (becoming the Interallied Mission to Poland

). They included: French diplomat, Jean Jules Jusserand

; Maxime Weygand

, chief of staff to Marshal Ferdinand Foch

, Supreme Commander of the victorious Entente; and British diplomat, Lord Edgar Vincent D'Abernon. The newest members of the mission achieved little; indeed, the crucial Battle of Warsaw was fought and won by the Poles before the mission could return and make its report. Nonetheless for many years, a myth persisted that it was the timely arrival of Allied forces that had saved Poland, a myth in which Weygand occupied the central role. Nonetheless Polish-French cooperation would continue. Eventually, on 21 February 1921, France and Poland entered into a formal military alliance

, which became an important factor during the subsequent Soviet–Polish negotiations.

units under the command of Gayk Bzhishkyan

crossed the Vistula

river, planning to take Warsaw from the west while the main attack came from the east. On 13 August, an initial Soviet attack was repulsed. The Polish 1st Army resisted a direct assault on Warsaw

as well as stopping the assault at Radzymin

.

The Soviet Western Front commander, Mikhail Tukhachevsky

, felt certain that all was going according to his plan. However, Polish military intelligence

had decrypted the Red Army's radio messages, and Tukhachevsky was actually falling into a trap set by Piłsudski and his Chief of Staff, Tadeusz Rozwadowski. The Soviet advance across the Vistula River in the north was moving into an operational vacuum, as there were no sizable Polish forces in the area. On the other hand, south of Warsaw, where the fate of the war was about to be decided, Tukhachevsky had left only token forces to guard the vital link between the Soviet northwest and southwest fronts. Another factor that influenced the outcome of the war was the effective neutralization of Budyonny's 1st Cavalry Army

, much feared by Piłsudski and other Polish commanders, in the battles around Lwów

. At Tukhachevsky's insistence the Soviet High Command had ordered the 1st Cavalry Army to march north toward Warsaw and Lublin

. However, Budyonny disobeyed the order due to a grudge between Tukhachevsky and Yegorov, commander of the southwest front.

Joseph Stalin

, then chief political commissar

of the Southwest Front, was engaged at Lwow, about 200 miles from Warsaw. The absence of his forces at the battle has been the subject of dispute. A perception arose that his absence was due to his desire to achieve 'military glory' at Lwow. Telegrams concerning the transfer of forces were exchanged. Leon Trotsky

interpreted Stalin's actions as insubordination; Richard Pipes

asserts that Stalin '...almost certainly acted on Lenin's orders' in not moving the forces to Warsaw. That the overall commander Sergey Kamenov allowed such insubordination, issued conflicting and confusing orders and did not act with the decisiveness of a commander in chief contributed greatly to the problems and defeat the Red forces suffered at this critical junction of the war.

The Polish 5th Army under General Władysław Sikorski counterattacked on 14 August from the area of the Modlin fortress

The Polish 5th Army under General Władysław Sikorski counterattacked on 14 August from the area of the Modlin fortress

, crossing the Wkra

River. It faced the combined forces of the numerically and materially superior Soviet 3rd and 15th Armies. In one day the Soviet advance toward Warsaw and Modlin had been halted and soon turned into retreat. Sikorski's 5th Army pushed the exhausted Soviet formations away from Warsaw in a lightning operation. Polish forces advanced at a speed of thirty kilometers a day, soon destroying any Soviet hopes for completing their enveloping manoeuvre in the north. By 16 August, the Polish counteroffensive had been fully joined by Marshal Piłsudski's "Reserve Army." Precisely executing his plan, the Polish force, advancing from the south, found a huge gap between the Soviet fronts and exploited the weakness of the Soviet "Mozyr Group" that was supposed to protect the weak link between the Soviet fronts. The Poles continued their northward offensive with two armies following and destroying the surprised enemy. They reached the rear of Tukhachevsky's forces, the majority of which were encircled by 18 August. Only that same day did Tukhachevsky, at his Minsk

headquarters 300 miles (482.8 km) east of Warsaw, become fully aware of the proportions of the Soviet defeat and ordered the remnants of his forces to retreat and regroup. He hoped to straighten his front line, halt the Polish attack, and regain the initiative, but the orders either arrived too late or failed to arrive at all.

Soviet armies in the center of the front fell into chaos. Tukhachevsky ordered a general retreat toward the Bug River

, but by then he had lost contact with most of his forces near Warsaw, and all the Bolshevik plans had been thrown into disarray by communication failures.

Bolshevik armies retreated in a disorganised fashion; entire divisions panicking and disintegrating. The Red Army's defeat was so great and unexpected that, at the instigation of Piłsudski's detractors, the Battle of Warsaw

is often referred to in Poland as the "Miracle at the Vistula". Previously unknown documents from Polish Central Military Archive found in 2004 proved that the successful breaking of Red Army radio communications cipher

s by Polish cryptographers played a great role in the victory.

Budyonny's

1st Cavalry Army's advance toward Lwów

was halted, first at the battle of Brody (29 July – 2 August), and then on 17 August at the Battle of Zadwórze

, where a small Polish force sacrificed itself to prevent Soviet cavalry from seizing Lwów and stopping vital Polish reinforcements from moving toward Warsaw. Moving through weakly defended areas, Budyonny's cavalry reached the city of Zamość

on 29 August and attempted to take it in the Battle of Zamość; however, he soon faced an increasing number of Polish units diverted from the successful Warsaw counteroffensive. On 31 August, Budyonny's cavalry finally broke off its siege of Lwów and attempted to come to the aid of Soviet forces retreating from Warsaw. The Soviet forces were intercepted and defeated by Polish cavalry

at the Battle of Komarów

near Zamość, the largest cavalry battle since 1813 and one of the last cavalry battles in history. Although Budyonny's army managed to avoid encirclement, it suffered heavy losses and its morale plummeted. The remains of Budyonny's 1st Cavalry Army retreated towards Volodymyr-Volynskyi

on 6 September and was defeated shortly thereafter at the Battle of Hrubieszów.

Tukhachevsky managed to reorganize the eastward-retreating forces and in September established a new defensive line running from the Polish–Lithuanian border to the north to the area of Polesie, with the central point in the city of Grodno in Belarus. The Polish Army broke this line in the Battle of the Niemen River

. Polish forces crossed the Niemen River and outflanked the Bolshevik forces, which were forced to retreat again. Polish forces continued to advance east on all fronts, repeating their successes from the previous year. After the early October Battle of the Szczara River, the Polish Army had reached the Ternopil

–Dubno

–Minsk

–Drisa line.

In the south, Petliura's Ukrainian forces defeated the Bolshevik 14th Army and on 18 September took control of the left bank of the Zbruch river. During the next month they moved east to the line Yaruha on the Dniester

-Sharharod-Bar

-Lityn.

, and with its army controlling the majority of the disputed territories, were willing to negotiate. The Soviets made two offers: one on 21 September and the other on 28 September. The Polish delegation made a counteroffer on 2 October. On the 5th, the Soviets offered amendments to the Polish offer, which Poland accepted. The Preliminary Treaty of Peace and Armistice

Conditions between Poland on one side and Soviet Ukraine and Soviet Russia on the other was signed on 12 October, and the armistice went into effect on 18 October. Ratifications were exchanged at Liepāja

on 2 November. Long negotiations of the final peace treaty ensued.

Meanwhile, Petliura's Ukrainian forces, which now numbered 23,000 soldiers and controlled territories immediately to the east of Poland, planned an offensive in Ukraine for 11 November but were attacked by the Bolsheviks on 10 November. By 21 November, after several battles, they were driven into Polish-controlled territory.

After the peace negotiations Poland did not maintain all the territories it had controlled at the end of hostilities. Due to their losses in and after the Battle of Warsaw, the Soviets offered the Polish peace delegation substantial territorial concessions in the contested borderland areas, closely resembling the border between the Russian Empire

After the peace negotiations Poland did not maintain all the territories it had controlled at the end of hostilities. Due to their losses in and after the Battle of Warsaw, the Soviets offered the Polish peace delegation substantial territorial concessions in the contested borderland areas, closely resembling the border between the Russian Empire

and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth before the first partition

of 1772. Polish resources were exhausted, however, and Polish public opinion was opposed to a prolongation of the war. The Polish government was also pressured by the League of Nations

, and the negotiations were controlled by Dmowski's National Democrats

. Piłsudski might have controlled the military, but parliament (Sejm

) was controlled by Dmowski: Piłsudski's support lay in the territories in the East, which were controlled by the Bolsheviks at the time of the elections, while the National Democrats' electoral support lay in central and western Poland. The peace negotiations were of a political nature. National Democrats, like Stanisław Grabski, who earlier had resigned his post to protest the Polish–Ukrainian alliance and now wielded much influence over the Polish negotiators, cared little for Piłsudski's vision of reviving Międzymorze

, the multicultural Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. This post-war situation proved a death blow to the Międzymorze project. More than one million Poles

, living mostly in the disputed territories, remained in the SU, systematically persecuted by Soviet authorities because of political, economical and religious reasons (see the Polish operation of the NKVD

).

The National Democrats in charge of the state also had few concerns about the fate of their Ukrainian ally, Petlura, and cared little that their political opponent, Piłsudski, felt honor-bound by his treaty obligations; his opponents did not hesitate to scrap the treaty. The National Democrats wanted only the territory that they viewed as 'ethnically or historically Polish' or possible to polonize. Despite the Red Army's crushing defeat at Warsaw and the willingness of Soviet chief negotiator Adolf Joffe to concede almost all disputed territory, the National Democrats' ideology allowed the Soviets to regain certain territories. The Peace of Riga

was signed on 18 March 1921, splitting the disputed territories in Belarus and Ukraine between Poland and Russia. The treaty, which Piłsudski called an "act of cowardice", and for which he apologized to the Ukrainians, actually violated the terms of Poland's military alliance with the Directorate of Ukraine

, which had explicitly prohibited a separate peace. Ukrainian allies of Poland found themselves interned by the Polish authorities. The internment worsened relations between Poland and its Ukrainian minority: those who supported Petliura were angered by the betrayal of their Polish ally, anger that grew stronger because of the assimilationist policies of nationalist inter-war Poland towards its minorities. To a large degree, this inspired the growing tensions and eventual violence

against Poles in the 1930s and 1940s.

The war and its aftermath also resulted in other controversies, such as the situation of prisoners of war

of both sides

, treatment of the civilian population and behaviour of some commanders like Stanisław Bułak-Bałachowicz or Vadim Yakovlev

. The Polish military successes in the autumn of 1920

allowed Poland to capture the Vilnius region

, where a Polish-dominated Governance Committee of Central Lithuania

(Komisja Rządząca Litwy Środkowej) was formed. A plebiscite was conducted, and the Vilnius Sejm

voted on 20 February 1922, for incorporation into Poland. This worsened Polish–Lithuanian relations for decades to come. However the loss of Vilnius might have safeguarded the very existence of the Lithuanian state in the interwar period. Despite an alliance with Soviets (Soviet-Lithuanian Treaty of 1920) and the war with Poland, Lithuania was very close to being invaded by the Soviets in summer 1920 and forcibly converted into a socialist republic. It was only the Polish victory against the Soviets in the Polish–Soviet War (and the fact that the Poles did not object to some form of Lithuanian independence) that derailed the Soviet plans and gave Lithuania an experience of interwar independence. Another controversy concerned the pogrom

s of Jews

, which have caused the United States to send a commission led by Henry Morgenthau, Sr.

to investigate the matter.

Military strategy in the Polish–Soviet War influenced Charles de Gaulle

Military strategy in the Polish–Soviet War influenced Charles de Gaulle

, then an instructor with the Polish Army who fought in several of the battles. He and Władysław Sikorski were the only military officers who, based on their experiences of this war, correctly predicted how the next one would be fought. Although they failed in the interbellum to convince their respective militaries to heed those lessons, early in World War II they rose to command of their armed forces in exile. The Polish–Soviet War also influenced Polish military doctrine, which for the next 20 years would place emphasis on the mobility of elite cavalry units.

In 1943, during the course of World War II, the subject of Poland's eastern borders was re-opened, and they were discussed at the Tehran Conference

. Winston Churchill

argued in favor of the 1920 Curzon Line

rather than the Treaty of Riga's borders, and an agreement among the Allies to that effect was reached at the Yalta Conference

in 1945. The Western Allies, despite having alliance treaties with Poland and despite Polish contribution

, also left Poland within the Soviet sphere of influence

. This became known in Poland as the Western Betrayal

.

Until 1989, while Communists held power in the People's Republic of Poland

, the Polish–Soviet War was omitted or minimized in Polish and other Soviet bloc countries' history books, or was presented as a foreign intervention during the Russian Civil War

to fit in with Communist ideology.

Lieutenant Józef Kowalski

, of Poland, is the last known living veteran from this war. He was awarded the Order of Polonia Restituta on his 110th birthday by the president of Poland.

the "Export of Revolution": The Russo-Polish War

Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, Second Commonwealth of Poland or interwar Poland refers to Poland between the two world wars; a period in Polish history in which Poland was restored as an independent state. Officially known as the Republic of Poland or the Commonwealth of Poland , the Polish state was...

and the Ukrainian People's Republic

Ukrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic or Ukrainian National Republic was a republic that was declared in part of the territory of modern Ukraine after the Russian Revolution, eventually headed by Symon Petliura.-Revolutionary Wave:...

—four states in post–World War I Europe. Poland, whose statehood had just been re-established by the Treaty of Versailles

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was one of the peace treaties at the end of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1919, exactly five years after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The other Central Powers on the German side of...

following the Partitions of Poland

Partitions of Poland

The Partitions of Poland or Partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth took place in the second half of the 18th century and ended the existence of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, resulting in the elimination of sovereign Poland for 123 years...

in the late 18th century, sought to secure territories it had lost at the time of partitions; the Soviet states aimed to control those same territories, which had been part of the Russian Empire

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

until the turbulent events of World War I. On the Soviet part, the ideological factor was also important, as the newly created communist state sought to spread its revolution to Central

Central Europe

Central Europe or alternatively Middle Europe is a region of the European continent lying between the variously defined areas of Eastern and Western Europe...

, and later Western Europe

Western Europe

Western Europe is a loose term for the collection of countries in the western most region of the European continents, though this definition is context-dependent and carries cultural and political connotations. One definition describes Western Europe as a geographic entity—the region lying in the...

. This is evident by Marshal Tukhachevsky's daily order to his troops: "Over the corpse of Poland leads the road to the world's fire. Towards Wilno, Minsk, Warsaw go!" Despite the final retreat of Russian forces and annihilation of their three field armies, historians don't universally agree on the question of victory.Russian and Polish historians tend to assign victory to their respective countries. Outside assessments vary, mostly between calling the result a Polish victory and inconclusive. Lenin, in his secret report to the 9th Conference of the Bolshevik Party on , called the outcome of the war, "In a word, a gigantic, unheard-of defeat." (See ) The Poles claimed a successful defense of their state, while the Soviets claimed a repulse of the Polish eastward invasion of Ukraine and Belarus, which they viewed as a part of the foreign intervention in the Russian Civil War

Allied Intervention in the Russian Civil War

The Allied intervention was a multi-national military expedition launched in 1918 during World War I which continued into the Russian Civil War. Its operations included forces from 14 nations and were conducted over a vast territory...

.

The Treaty of Versailles

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was one of the peace treaties at the end of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1919, exactly five years after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The other Central Powers on the German side of...

had only vaguely defined the frontiers between Poland and Bolshevik Russia, and post-war events created turmoil—the Russian Revolution of 1917

Russian Revolution of 1917

The Russian Revolution is the collective term for a series of revolutions in Russia in 1917, which destroyed the Tsarist autocracy and led to the creation of the Soviet Union. The Tsar was deposed and replaced by a provisional government in the first revolution of February 1917...

, the crumbling of the Russian

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

, German

German Empire

The German Empire refers to Germany during the "Second Reich" period from the unification of Germany and proclamation of Wilhelm I as German Emperor on 18 January 1871, to 1918, when it became a federal republic after defeat in World War I and the abdication of the Emperor, Wilhelm II.The German...

and Austrian

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary , more formally known as the Kingdoms and Lands Represented in the Imperial Council and the Lands of the Holy Hungarian Crown of Saint Stephen, was a constitutional monarchic union between the crowns of the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary in...

empires, the Russian Civil War

Russian Civil War

The Russian Civil War was a multi-party war that occurred within the former Russian Empire after the Russian provisional government collapsed to the Soviets, under the domination of the Bolshevik party. Soviet forces first assumed power in Petrograd The Russian Civil War (1917–1923) was a...

, the Central Powers

Central Powers

The Central Powers were one of the two warring factions in World War I , composed of the German Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulgaria...

' withdrawal from the eastern front

Eastern Front (World War I)

The Eastern Front was a theatre of war during World War I in Central and, primarily, Eastern Europe. The term is in contrast to the Western Front. Despite the geographical separation, the events in the two theatres strongly influenced each other...

, and the attempts of Ukraine

Ukrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic or Ukrainian National Republic was a republic that was declared in part of the territory of modern Ukraine after the Russian Revolution, eventually headed by Symon Petliura.-Revolutionary Wave:...

and Belarus

Belarusian National Republic

The Belarusian People's Republic was a self-declared independent Belarusian state, which declared independence in 1918. It is also called the Belarusian Democratic Republic or the Belarusian National Republic, in order to distinguish it from Communist People's Republics...

to establish independence. Poland's Chief of State, Józef Piłsudski, felt the time was right to expand Polish borders as far east as feasible, to be followed by a Polish-led Intermarum

Miedzymorze

Międzymorze was a plan, pursued after World War I by Polish leader Józef Piłsudski, for a federation, under Poland's aegis, of Central and Eastern European countries...

federation of East-Central-European states as a bulwark against the re-emergence of German and Russian imperialism

Imperialism

Imperialism, as defined by Dictionary of Human Geography, is "the creation and/or maintenance of an unequal economic, cultural, and territorial relationships, usually between states and often in the form of an empire, based on domination and subordination." The imperialism of the last 500 years,...

s. Lenin

Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Lenin was a Russian Marxist revolutionary and communist politician who led the October Revolution of 1917. As leader of the Bolsheviks, he headed the Soviet state during its initial years , as it fought to establish control of Russia in the Russian Civil War and worked to create a...

, meanwhile, saw Poland as the bridge the Red Army

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army started out as the Soviet Union's revolutionary communist combat groups during the Russian Civil War of 1918-1922. It grew into the national army of the Soviet Union. By the 1930s the Red Army was among the largest armies in history.The "Red Army" name refers to...

had to cross to assist other communist movements

Communist Party of Germany

The Communist Party of Germany was a major political party in Germany between 1918 and 1933, and a minor party in West Germany in the postwar period until it was banned in 1956...

and bring about other European revolutions.

By 1919, Polish forces had taken control of much of Western Ukraine

Western Ukraine

Western Ukraine may refer to:* Generally, the territories in the West of Ukraine* Eastern Galicia* West Ukrainian National Republic...

, emerging victorious from the Polish–Ukrainian War. The West Ukrainian People's Republic, led by Yevhen Petrushevych

Yevhen Petrushevych

Yevhen Petrushevych was a Ukrainian lawyer, politician, and president of the Western Ukrainian National Republic formed after the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian empire in 1918.-Biography:He was born on June 3, 1863, in the town of Busk, of Galicia in the clerical...

, had tried unsuccessfully to create a Ukrainian state on territories to which both Poles and Ukrainians laid claim. At the same time in the Russian part of Ukraine Symon Petliura tried to defend and strengthen the Ukrainian People's Republic

Ukrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic or Ukrainian National Republic was a republic that was declared in part of the territory of modern Ukraine after the Russian Revolution, eventually headed by Symon Petliura.-Revolutionary Wave:...

, but as the Bolsheviks began to gain the upper hand in the Russian Civil War, they started to advance westward towards the disputed Ukrainian territories causing Petliura's forces to retreat to Podolia

Podolia

The region of Podolia is an historical region in the west-central and south-west portions of present-day Ukraine, corresponding to Khmelnytskyi Oblast and Vinnytsia Oblast. Northern Transnistria, in Moldova, is also a part of Podolia...

. By the end of 1919 a clear front had formed as Petliura decided to ally with Piłsudski. Border skirmishes escalated into open warfare following Piłsudski's major incursion further east into Ukraine in April 1920. The Polish offensive was met by an initially successful Red Army counterattack

Counterattack

A counterattack is a tactic used in response against an attack. The term originates in military strategy. The general objective is to negate or thwart the advantage gained by the enemy in attack and the specific objectives are usually to regain lost ground or to destroy attacking enemy units.It is...

. The Soviet operation threw the Polish forces back westward all the way to the Polish capital, Warsaw

Warsaw

Warsaw is the capital and largest city of Poland. It is located on the Vistula River, roughly from the Baltic Sea and from the Carpathian Mountains. Its population in 2010 was estimated at 1,716,855 residents with a greater metropolitan area of 2,631,902 residents, making Warsaw the 10th most...

, while the Directorate of Ukraine

Directorate of Ukraine

The Directorate, or Directory was a provisional revolutionary state committee of the Ukrainian National Republic, formed in 1918 by the Ukrainian National Union in rebellion against Skoropadsky's regime....

fled to Western Europe. Meanwhile, Western fears of Soviet troops arriving at the German frontiers increased the interest of Western powers

Interallied Mission to Poland

Interallied Mission to Poland was a diplomatic mission launched by David Lloyd George on July 21, 1920, at the height of the Polish-Soviet War, weeks before the decisive Battle of Warsaw...

in the war. In midsummer, the fall of Warsaw seemed certain but in mid-August the tide had turned again as the Polish forces achieved an unexpected and decisive victory at the Battle of Warsaw

Battle of Warsaw (1920)

The Battle of Warsaw sometimes referred to as the Miracle at the Vistula, was the decisive battle of the Polish–Soviet War. That war began soon after the end of World War I in 1918 and lasted until the Treaty of Riga resulted in the end of the hostilities between Poland and Russia in 1921.The...

. In the wake of the Polish advance eastward, the Soviets sued for peace and the war ended with a ceasefire

Ceasefire

A ceasefire is a temporary stoppage of a war in which each side agrees with the other to suspend aggressive actions. Ceasefires may be declared as part of a formal treaty, but they have also been called as part of an informal understanding between opposing forces...

in October 1920. A formal peace treaty

Peace treaty

A peace treaty is an agreement between two or more hostile parties, usually countries or governments, that formally ends a state of war between the parties...

, the Peace of Riga

Peace of Riga

The Peace of Riga, also known as the Treaty of Riga; was signed in Riga on 18 March 1921, between Poland, Soviet Russia and Soviet Ukraine. The treaty ended the Polish-Soviet War....

, was signed on 18 March 1921, dividing the disputed territories between Poland and Soviet Russia. The war largely determined the Soviet–Polish border for the period between the World Wars. Much of the territory ceded to Poland in the Treaty of Riga became part of the Soviet Union after World War II, when Poland's eastern borders were redefined by the Allies

Allies of World War II

The Allies of World War II were the countries that opposed the Axis powers during the Second World War . Former Axis states contributing to the Allied victory are not considered Allied states...

in close accordance with the British-drawn Curzon Line

Curzon Line

The Curzon Line was put forward by the Allied Supreme Council after World War I as a demarcation line between the Second Polish Republic and Bolshevik Russia and was supposed to serve as the basis for a future border. In the wake of World War I, which catalysed the Russian Revolution of 1917, the...

of 1920.

Names and dates

The war is called by several names. “Polish–Soviet War” may be the most common, but is potentially confusing since “Soviet” usually refers to the Soviet Union, which (by contrast with “Soviet RussiaRussian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic , commonly referred to as Soviet Russia, Bolshevik Russia, or simply Russia, was the largest, most populous and economically developed republic in the former Soviet Union....

”) did not officially exist until . Alternative names include “Russo–Polish War [or Polish–Russian War] of 1919–1921”See for instance Russo-Polish War in Encyclopædia Britannica

Encyclopædia Britannica

The Encyclopædia Britannica , published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., is a general knowledge English-language encyclopaedia that is available in print, as a DVD, and on the Internet. It is written and continuously updated by about 100 full-time editors and more than 4,000 expert...

“The conflict began when the Polish head of state Józef Piłsudski formed an alliance with the Ukrainian nationalist leader Symon Petlyura and their combined forces began to overrun Ukraine, occupying Kiev on 7 May.” (to distinguish it from earlier Polish–Russian wars) and “Polish–Bolshevik War”. This second term (or just “Bolshevik War” ) is most common in Polish sources. In some Polish sources it is also referred as the "War of 1920" (Polish: Wojna 1920 roku).For example: 1) Sąsiedzi wobec wojny 1920 roku. Wybór dokumentów.

2) Wojna 1920 roku na Mazowszu i Podlasiu

3) Nad Wisłą i Wkrą. Studium do polsko–radzieckiej wojny 1920 roku

Other points of contention are the starting and ending dates of the war. For example, Encyclopædia Britannica

Encyclopædia Britannica

The Encyclopædia Britannica , published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., is a general knowledge English-language encyclopaedia that is available in print, as a DVD, and on the Internet. It is written and continuously updated by about 100 full-time editors and more than 4,000 expert...

begins its article with the date (1919–1920), but then states "Although there had been hostilities between the two countries during 1919, the conflict began when the Polish head of state Józef Pilsudski formed an alliance with the Ukrainian nationalist leader Symon Petlyura (21 April 1920) and their combined forces began to overrun Ukraine, occupying Kiev on 7 May." while the Polish Internetowa encyklopedia PWN as well as some Western historians—like Norman Davies

Norman Davies

Professor Ivor Norman Richard Davies FBA, FRHistS is a leading English historian of Welsh descent, noted for his publications on the history of Europe, Poland, and the United Kingdom.- Academic career :...

—consider 1919 as the starting year of the war. The ending date is given as either 1920 or 1921; this confusion stems from the fact that while the ceasefire

Ceasefire

A ceasefire is a temporary stoppage of a war in which each side agrees with the other to suspend aggressive actions. Ceasefires may be declared as part of a formal treaty, but they have also been called as part of an informal understanding between opposing forces...

was put in force in the autumn of 1920, the official treaty ending the war was signed months later, in March 1921.

While the events of 1919 can be described as a border conflict—and only in early 1920 did both sides realize they were engaged in all-out war—the conflicts that took place in 1920 were an inevitable escalation of fighting that began in earnest a year earlier. In the end, the events of 1920 were a logical, though unforeseen, consequence of the 1919 prelude.

Prelude

Kievan Rus'

Kievan Rus was a medieval polity in Eastern Europe, from the late 9th to the mid 13th century, when it disintegrated under the pressure of the Mongol invasion of 1237–1240....

. After a period of internecine wars and the Mongolian invasion of 1240, they became objects of expansion for Poland and Lithuania. In the first half of the 14th century, Kiev and land between the Dnieper, Pripyat

Pripyat River

The Pripyat River or Prypiat River is a river in Eastern Europe, approximately long. It flows east through Ukraine, Belarus, and Ukraine again, draining into the Dnieper....

, and Dvina rivers became part of Lithuania, and in 1352 the Galicia-Volyn principality was split between Poland and Lithuania. In 1569, according to the Union of Lublin

Union of Lublin

The Union of Lublin replaced the personal union of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania with a real union and an elective monarchy, since Sigismund II Augustus, the last of the Jagiellons, remained childless after three marriages. In addition, the autonomy of Royal Prussia was...

between Poland and Lithuania, some of the Ukrainian lands passed to the Polish crown. Between 1772–1795, much of the Eastern Slavic territories became part of Russia. After the Congress of Vienna

Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna was a conference of ambassadors of European states chaired by Klemens Wenzel von Metternich, and held in Vienna from September, 1814 to June, 1815. The objective of the Congress was to settle the many issues arising from the French Revolutionary Wars, the Napoleonic Wars,...

in 1814–1815, much of the territory of the Duchy of Warsaw

Duchy of Warsaw

The Duchy of Warsaw was a Polish state established by Napoleon I in 1807 from the Polish lands ceded by the Kingdom of Prussia under the terms of the Treaties of Tilsit. The duchy was held in personal union by one of Napoleon's allies, King Frederick Augustus I of Saxony...

(Poland) was transferred to Russian control.

In the aftermath of World War I

Aftermath of World War I

The fighting in World War I ended in western Europe when the Armistice took effect at 11:00 am GMT on November 11, 1918, and in eastern Europe by the early 1920s. During and in the aftermath of the war the political, cultural, and social order was drastically changed in Europe, Asia and Africa,...

, the map of Central

Central Europe

Central Europe or alternatively Middle Europe is a region of the European continent lying between the variously defined areas of Eastern and Western Europe...

and Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is the eastern part of Europe. The term has widely disparate geopolitical, geographical, cultural and socioeconomic readings, which makes it highly context-dependent and even volatile, and there are "almost as many definitions of Eastern Europe as there are scholars of the region"...

had drastically changed. Germany's defeat rendered its plans for the creation of Eastern European puppet state

Puppet state

A puppet state is a nominal sovereign of a state who is de facto controlled by a foreign power. The term refers to a government controlled by the government of another country like a puppeteer controls the strings of a marionette...

s (Mitteleuropa

Mitteleuropa

Mitteleuropa is the German term equal to Central Europe. The word has political, geographic and cultural meaning. While it describes a geographical location, it also is the word denoting a political concept of a German-dominated and exploited Central European union that was put into motion during...

) obsolete, and the Russian Empire collapsed, resulting in a revolution

Russian Revolution of 1917