Sino-Soviet split

Encyclopedia

In political science

, the term Sino–Soviet split (1960–1989) denotes the worsening of political and ideologic

relations between the People's Republic of China

(PRC) and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

(USSR) during the Cold War

(1945–1991). The doctrinal

divergence derived from Chinese and Russian national interest

s, and from the régimes' respective interpretations

of Marxism

: Maoism

and Marxism–Leninism. In the 1950s and the 1960s, ideological debate between the Communist parties of Russia and China also concerned the possibility of peaceful coexistence

with the capitalist

West

. Yet, to the Chinese public, Mao Zedong

proposed a belligerent attitude towards capitalist

countries, an initial rejection of peaceful coexistence, which he perceived as Marxist revisionism from the Russian Soviet Union. Moreover, since 1956, the PRC and the USSR had (secretly) diverged about Marxist ideology, and, by 1961, when the doctrinal differences proved intractable, the Communist Party of China

formally denounced the Soviet variety of Communism

as a product of “The Revisionist Traitor Group of Soviet Leadership”, the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

, headed by Nikita Krushchev.

(CCP), led by Mao Zedong

, fought the Second Sino-Japanese War

(1939–45) against the Empire of Japan

, whilst simultaneously fighting the Chinese Civil War

against the Nationalist Kuomintang

, led by Chiang Kai-shek

. In fighting the over-lapping wars, Mao ignored much of the politico-military advice and direction from Joseph Stalin

and the Comintern

, because of the practical difficulty in applying traditional Leninist

revolutionary theory to China, because there were only peasants, and no urban working class

, as in Russia.

During the Second World War

(1939–45) Stalin had urged Mao into a joint, anti-Japanese coalition with Chiang. After the war, Stalin advised Mao against seizing power, and to negotiate with Chiang, because Stalin had signed a Treaty of Friendship and Alliance with the Nationalists in mid-1945; Mao followed Stalin's lead, calling him “the only leader of our party”. Unwisely, Chiang Kai-Shek opposed USSR’s accession of Tannu Uriankhai

, a former Qing Empire province; Stalin broke the treaty requiring Soviet withdrawal from Manchuria three months after Japan’s surrender, and gave Manchuria to Mao. Soon afterwards, a two-month Moscow

visit by Mao culminated in the Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship and Alliance (1950), which comprised a $300 million low-interest loan and a 30-year military alliance.

Simultaneously, Beijing had begun trying to displace Moscow as the ideological leader of the world Communist movement. Mao (and his supporters) had advocated the idea that Asian and world communist movements should emulate China’s model of peasant revolution, not Soviets model of urban revolution. In 1947, Mao gave US journalist Anna Louise Strong

Simultaneously, Beijing had begun trying to displace Moscow as the ideological leader of the world Communist movement. Mao (and his supporters) had advocated the idea that Asian and world communist movements should emulate China’s model of peasant revolution, not Soviets model of urban revolution. In 1947, Mao gave US journalist Anna Louise Strong

documents, directing her to “show them to Party leaders in the United States and Europe”, but he did not think it was “necessary to take them to Moscow”. Earlier, she had written the article “The Thought of Mao Tse-Tung” and the book Dawn Out of China, reporting that his intellectual accomplishment was “to change Marxism from a European to an Asiatic form... in ways of which neither Marx

nor Lenin

could dream”, which the Soviet government banned in the USSR. Years later, at the first international Communist conclave in Beijing, Mao advocate Liu Shaoqi

praised the “Mao Tse-tung road” as the correct road to communist revolution, warning it was incorrect to follow any other road; moreover, he praised neither Stalin nor the Soviet communist model, as had been the practice among Communists. Yet, with political and military tensions at crisis in the Korean Peninsula, and a fear of US military intervention there, geopolitical circumstances disallowed the USSR and China any ideological split, hence their alliance continued.

During the 1950s, Soviet-guided China followed the Soviet model of centralized economic development, emphasising heavy industry

, and delegating consumer goods to secondary priority; however, by the late 1950s, Mao had developed different ideas for how China could directly advance to the communist stage of Socialism (per the Marxist denotation), through the mobilization of China’s workers. These ideas progressed to the Great Leap Forward

(1958–61).

After Joseph Stalin’s death in 1953 there was a temporary revival of Sino-Soviet friendship; thus, in 1954, the Soviets calmed Mao with an official visit by Premier Nikita Khrushchev

that featured the formal hand-over of the Lüshun (Port Arthur) naval base to China. The Soviets provided technical aid in 156 industries in China’s first five-year plan, and 520 million rubles in loans; thus at the Geneva Conference of 1954, the PRC and the USSR jointly persuaded the Democratic Republic of Vietnam

, led by Ho Chi Minh

, to temporarily accept the West’s division of Vietnam

at the 17th parallel north

.

Premier Khrushchev’s post-Stalin policies began to irritate Mao; disagreeing when Khruschev denounced Stalin with On the Personality Cult and its Consequences

speech to the Twentieth Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

in 1956; and when he restored relations with Yugoslavia

, led by Josip Broz Tito

, whom Stalin had denounced

in 1948. These occurrences shocked Mao, who had supported Stalin ideologically and politically, because Khrushchev was dismantling Mao’s support of the USSR with public rejections of most of Stalin’s leadership and actions — such as announcing the end of the Cominform

, and (most troubling to Mao), de-emphasising the core Marxist-Leninist thesis of inevitable war between capitalism

and socialism

. Resultantly, contradicting Stalin, Khrushchev was advocating the idea of “Peaceful Coexistence

”, between communist and capitalist nations — which directly challenged Mao’s “lean-to-one-side” foreign policy, adopted after the Chinese Civil War, when he feared direct Japanese or US military intervention, the circumstances that pragmatically required a PRC–Soviet alliance. In de-Stalinizing the USSR, Khrushchev was dissolving the condition that had made the Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship (1950) attractive to China. Mao thought that the Soviets were retreating ideologically and militarily — from Marxism-Leninism and the global struggle to achieve global communism

, and by apparently no longer guaranteeing support to China in a Sino-American war; therefore, the roots of the Sino-Soviet ideological split were established by 1959.

In 1959, Premier Khrushchev met with US President Dwight Eisenhower (1953–61) to decrease Soviet–American tensions and with the Western world

In 1959, Premier Khrushchev met with US President Dwight Eisenhower (1953–61) to decrease Soviet–American tensions and with the Western world

in the Cold War. Moreover, the USSR was astonished by the Great Leap Forward

, had renounced aiding Chinese nuclear weapon

s development, and refused to side with them in the Sino-Indian War

(1962), by maintaining a moderate relation with India

— actions deemed offensive by Mao as Chinese Leader. Hence, he perceived Khrushchev as too-appeasing with the West, despite Soviet caution in international politics that threatened nuclear warfare

(i.e., the US, UK and USSR were nuclear powers by the late 1950s), wherein the USSR managed superpower confrontations such as the status of post-war Berlin

.

At first, the Sino-Soviet split manifested itself indirectly; arguments between the CPSU and the CPC criticized the client states of the other; China denounced Yugoslavia and Tito, the USSR denounced Enver Hoxha

and the People's Socialist Republic of Albania

; but, in 1960, they criticized each other in the Romanian Communist Party

congress, when Khrushchev and Peng Zhen

openly argued. Premier Khrushchev insulted Chairman Mao Zedong as “a nationalist, an adventurist, and a deviationist”. In turn, Mao insulted Khrushchev as a Marxist revisionist, criticizing him as “patriarchal, arbitrary and tyrannical”. In follow-up, Khrushchev denounced China with an eighty-page letter to the conference.

Khrushchev also withdrew nearly all Soviet technical experts from China, leaving some major projects in an unfinished state. Many blueprints and specifications were also withdrawn.

In November 1960, at a congress of 81 Communist parties in Moscow, the Chinese argued with the Soviets and with most other Communist party delegations — yet compromised to avoid a formal ideologic splitting; nonetheless, in October 1961, at the 22nd Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union they again argued openly. In December, the USSR severed diplomatic relations with the People’s Socialist Republic of Albania, graduating the Soviet–Chinese ideological dispute from between political parties to between nation-states.

In 1962, the PRC and the USSR broke relations because of their international actions; Chairman Mao criticized Premier Khrushchev for withdrawing from fighting the US in the Cuban missile crisis

(1962) — “Khrushchev has moved from adventurism to capitulationism”; Khrushchev replied that Mao’s confrontational policies would provoke a nuclear war

. Simultaneously, the USSR sided with India against China in the Sino-Indian War

(1962). Each régime followed these actions with formal ideological statements; in June 1963, the PRC published The Chinese Communist Party’s Proposal Concerning the General Line of the International Communist Movement http://www.etext.org/Politics/MIM/classics/mao/polemics/index.html, and the USSR replied with an Open Letter of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union; http://web.archive.org/web/20071225024740/www.etext.org/Politics/MIM/classics/mao/polemics/sevenlet.html these were the final, formal communications between the two Communist parties. Furthermore, by 1964, Chairman Mao asserted that a counter-revolution in the USSR had re-established capitalism

there; consequently, the Chinese and Soviet Communist parties broke relations, and the Warsaw Pact

Communist parties followed Soviet suit.

After Leonid Brezhnev

deposed Premier Khrushchev in October 1964, the Chinese Prime Minister Zhou Enlai

travelled to Moscow, in November, to speak with the new leaders of the USSR, Brezhnev and Alexei Kosygin, but returned disappointed to China, reporting to Mao that the Soviets remained firm; undeterred, Chairman Mao denounced “Khrushchevism without Khrushchev”, continuing the polemical.

and Socialist

countries, the Sino–Soviet split imbalanced the 1945 bipolar configuration of the Cold War

as an ideologic competition exclusively between the U.S. and the USSR; the inter-communist rivalry transformed the Cold War into a tripolar geopolitical

contest.

(1966–76) to rid himself of internal enemies and re-establish his sole leadership of party and country; and to prevent the development of Russian-style bureaucratic communism of the USSR. He closed the schools and universities and organized the students in the Red Guard, a thought police

politically commissioned to discover, denounce, and persecute teachers, intellectuals

, and government officials who might be counter-revolutionaries and secret bourgeois, all of which enforced the cult of personality

of Chairman Mao. In purging the enemies of the state from Chinese society, the Red Guard divided into factions, and their subsequent violence provoked civil war in some parts of China; Mao had the Army suppress the Red Guard factions; and when factionalism occurred in the Army, Mao dispersed the Red Guard, and then began to rebuild the Chinese Communist Party.

The political house-cleaning that was the Cultural Revolution stressed, strained, and broke China’s political relations with the USSR, and relations with the West

. Nevertheless, despite the “Maoism vs. Marxism–Leninism” differences interpreting Marxism

, Russia and China aided North Vietnam

, headed by Ho Chi Minh

, in fighting the Vietnam War

(1945–75), which Maoism

defined as a peasant revolution against foreign imperialism

. The Chinese allowed Soviet matériel across China for the North, to prosecute the war against the Republic of Vietnam

, a U.S. client state. In that time, besides the Socialist People's Republic of Albania, only the Communist Party of Indonesia

advocated the Maoist

policy of peasant revolution.

split, between Communist political parties, had escalated to small-scale warfare between Russia and China; thereby, in January 1967, Red Guards

attacked the Soviet embassy in Beijing. Earlier, in 1966, the Chinese had revived the matter of the Russo-Chinese border that was demarcated in the 19th-century, and imposed upon the Qing Dynasty

(1644–1912) monarchy by means of unequal treaties that virtually annexed Chinese territory to Tsarist Russia. Despite not asking the return of territory, the Chinese did ask the USSR to formally (publicly) acknowledge that said border, established with the Treaty of Aigun

(1858) and the Convention of Peking

(1860), was an historic Russian injustice against China; the Soviet government ignored the matter. Then, in 1968, the Red Guard purge

s meant to restore doctrinal orthodoxy

to China had provoked civil war in parts of the country, which Mao resolved with the People's Liberation Army

suppressing the pertinent cohorts of the Red Guard; the excesses of the Red Guard and of the Cultural Revolution declined. Mao required internal political equilibrium in order to protect China from the strategic and military vulnerabilities that resulted from its political isolation from the community of nations.

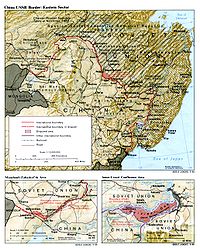

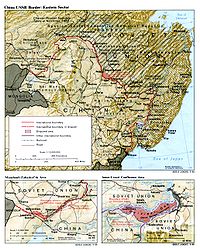

had amassed along the 4,380 km (2,738 mi.) border with China — especially at the Xinjiang

frontier, in north-west China, where the Soviets might readily induce Turkic

separatists to insurrection. Militarily, in 1961, the USSR had 12 divisions and 200 aeroplanes at that border; in 1968, there were 25 divisions, 1,200 aeroplanes, and 120 medium-range missiles. Moreover, although China had exploded its first nuclear weapon

(the 596 Test), in October 1964, at Lop Nur

basin, the People's Liberation Army

was militarily inferior to the Soviet Army. By March 1969, Sino–Russian border politics became the Sino-Soviet border conflict

at the Ussuri River

and on Damansky–Zhenbao Island; more small-scale warfare occurred at Tielieketi

in August. In The Coming War Between Russia and China (1969), US journalist Harrison Salisbury

reported that Soviet sources implied a possible first strike

against the Lop Nur

basin nuclear weapons testing site. The U.S. warned the USSR that a nuclear attack against China would precipitate a world-wide war; the USSR relented. Aware of that possibility, China built large-scale underground shelters, such as Beijing’s Underground City

, and military shelters such as the Underground Project 131

command center, in Hubei

, and the "816 Project" nuclear research center in Fuling

, Chongqing

.

, the Communist combatants withdrew. In September, Soviet Minister Alexei Kosygin secretly visited Beijing to speak with Premier Zhou Enlai

, and in October, the PRC and the USSR began discussing border-demarcation. Although they did not resolve the border demarcation matters, the meetings restored diplomatic communications; by 1970, Mao understood that the PRC could not simultaneously fight the USSR and the USA, whilst suppressing internal disorder. Moreover, as the Vietnam War

continued, and Chinese anti-American rhetoric continued, Mao perceived the USSR as the greater threat, and thus pragmatically sought rapprochement with the US, in confronting the USSR. In July 1971, U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger

secretly visited Beijing to prepare the February 1972 head-of-state visit to China by U.S. President Richard Nixon

. Moreover, the diplomatically offended Soviet Union also convoked a summit meeting with President Nixon, thus establishing the Washington–Beijing–Moscow diplomatic relationship, which emphasized the tripolar nature of the Cold War, occasioned by the ideological Sino–Soviet split begun in 1956.

Concerning the 4,380 km (2,738 mi.) Sino–Soviet border, Soviet counter-propaganda advertised against the PRC’s drawing attention to the unequal Treaty of Aigun

(1858) and the Convention of Peking

(1860). Moreover, between 1972 and 1973, the USSR deleted the Chinese and Manchu place-names — Iman (伊曼, Yiman), Tetyukhe (from 野猪河, yĕzhūhé), and Suchan — from the Soviet Far East map, and replaced them with the Russian place-names Dalnerechensk

, Dalnegorsk

, and Partizansk

. In the Stalinist

tradition, the pre–1860 Chinese presence in lands Tsarist Russia acquired with, the Treaty of Aigun and the Convention of Peking, became a politically incorrect

subject in the Soviet press, “inconvenient” museum exhibits were removed from public view, and the Jurchen-script

text about the Jin Dynasty stele

, supported by a stone tortoise

in the Khabarovsk

Museum, was covered with cement.

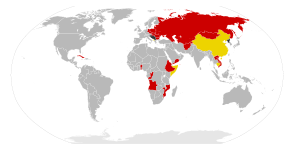

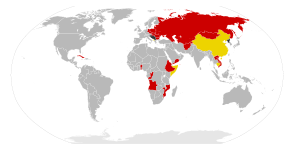

and the Middle East

, where the Soviet Union and Red China funded and supported opposed political parties, militias, and states, notably the Ogaden War

(1977–1978) between Ethiopia and Somalia, the Rhodesian Bush War

(1964–1979), the Zimbabwean Gukurahundi

(1980–1987), the Angolan Civil War

(1975–2002), the Mozambican Civil War

(1977–1992), and factions of the Palestinian people

.

, Mao’s executive officer, concluded the radical phase of the Cultural Revolution

(1966–76); afterwards, China resumed political normality, until Mao’s death in September 1976, and the emergence of the politically radical Gang of Four. The re-establishment of Chinese domestic tranquility ended armed confrontation with the USSR, but did not improve diplomatic relations, because, in 1973, the Soviet Army garrisons at the Russo–Chinese border were twice as large as the 1969 garrisons. That continued military threat prompted the Chinese to denounce “Soviet social-imperialism

”, and to accuse the USSR of being an enemy of world revolution

— despite the PRC having discontinued sponsoring world revolution since 1972, when it pursued a negotiated end to the Vietnam War

(1945–75).

, and appointed him head of the internal modernization programs in 1977. Whilst reversing Mao’s policies (without attacking him), the politically moderate Deng’s political and economic reforms began China’s transition from a planned economy

to a semi–capitalist

mixed economy

, which he furthered with strengthened commercial and diplomatic relations with the West. In 1979, on the 30th anniversary of the foundation of the PRC, the government of Deng Xiaoping denounced the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution as a national failure; and, in the 1980s, pursued pragmatic

policies such as “seeking truth from facts” and the “Chinese road to socialism”, which withdrew the PRC from the high-level abstractions of ideology

, polemic

, and Russian Marxist revisionism

; the Sino–Soviet split had lost some political importance.

wherein the Russian and Chinese hegemonies

conflicted in the pursuit of national interests

. The initial Russo–Chinese proxy war

occurred in Indochina

, in 1975, where the Communist victory of the National Liberation Front (Viet Cong) and of North Vietnam

in the thirty-year Vietnam War

had produced a post–colonial

Indochina that featured pro-Soviet, nationalist régimes in Vietnam (Socialist Republic of Vietnam) and Laos (Lao People's Democratic Republic

), and a pro-Chinese nationalist régime in Cambodia (Democratic Kampuchea

). At first, Vietnam ignored the Khmer Rouge

domestic reorganization of Cambodia, by the Pol Pot

régime (1975–79), as an internal matter, until the Khmer Rouge attacked the ethnic Vietnamese populace of Cambodia, and the border with Vietnam; the counter-attack precipitated the Cambodian–Vietnamese War (1975–79) that deposed Pol Pot in 1978. In response, the PRC denounced the Vietnamese deposition of their Maoist

client-leader, and retaliated by invading northern Vietnam, in the Sino-Vietnamese War

(1979); in turn, the USSR denounced the PRC’s invasion of Vietnam.

In December 1979, the USSR invaded the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan

to sustain the Afghan Communist government. The PRC viewed the Soviet invasion as a local feint, within Russia’s greater geopolitical

encirclement of China. In response, the PRC entered a tri-partite alliance with the U.S. and Pakistan

, to sponsor Islamist Afghan armed resistance to the Soviet Occupation

(1979–89). (cf. Operation Storm-333

) Meanwhile, the Sino–Soviet split became manifest when Deng Xiaoping

, the Paramount Leader

of China, required the removal of “three obstacles” so that Sino-Soviet relations might improve:

Moreover, from 1981 to 1982, Deng Xiaoping distanced the PRC from the United States because of its weapons sales to the Nationalist Republic of China

in Taiwan island, and because the PRC was the junior partner in the current Sino–American relations. Hence, in September 1982, the 12th Chinese Communist Party Congress declared that the PRC would pursue an “independent foreign policy”. Meanwhile, in March 1982 in Tashkent

, USSR Secretary Leonid Brezhnev

gave a speech conciliatory towards the PRC, and Deng Xiaoping took advantage of Brezhnev’s proffered conciliation; in autumn of 1982, Sino-Soviet relations resumed (semi-annually), at the vice-ministerial level. Three years later, in 1985, when Mikhail Gorbachev

became President of the USSR, he worked to restore political relations with China; he reduced the Soviet Army garrisons at the Sino–Soviet border, in Mongolia, and resumed trade, and dropped the 1969 border-demarcation matter. Nonetheless, the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan remained unresolved, and Sino-Soviet diplomacy

remained cool, which circumstance allowed the Reagan government to sell American weapons to Communist China and so geopolitically counter the USSR in the Russo–American aspect of the three-fold Cold War.

and glasnost

. Since the PRC did not officially recognise the USSR as a socialist state, there was no official opinion about Gorbachev’s reformation of Soviet socialism

; yet privately, the Chinese Communists thought the USSR unprepared for such political and social reforms without first reforming the economy of the USSR. The Chinese perspective derived from how the Paramount Leader

, Deng Xiaoping, effected economic reform with a semi-capitalist mixed economy

, while the political power remained with the Chinese Communist Party. Ultimately, Gorbachev's reformation of Russian society ended Soviet-Communist government, and provoked the dissolution of the Soviet Union

in 1991.

Political science

Political Science is a social science discipline concerned with the study of the state, government and politics. Aristotle defined it as the study of the state. It deals extensively with the theory and practice of politics, and the analysis of political systems and political behavior...

, the term Sino–Soviet split (1960–1989) denotes the worsening of political and ideologic

Ideology

An ideology is a set of ideas that constitutes one's goals, expectations, and actions. An ideology can be thought of as a comprehensive vision, as a way of looking at things , as in common sense and several philosophical tendencies , or a set of ideas proposed by the dominant class of a society to...

relations between the People's Republic of China

China

Chinese civilization may refer to:* China for more general discussion of the country.* Chinese culture* Greater China, the transnational community of ethnic Chinese.* History of China* Sinosphere, the area historically affected by Chinese culture...

(PRC) and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

(USSR) during the Cold War

Cold War

The Cold War was the continuing state from roughly 1946 to 1991 of political conflict, military tension, proxy wars, and economic competition between the Communist World—primarily the Soviet Union and its satellite states and allies—and the powers of the Western world, primarily the United States...

(1945–1991). The doctrinal

Doctrine

Doctrine is a codification of beliefs or a body of teachings or instructions, taught principles or positions, as the body of teachings in a branch of knowledge or belief system...

divergence derived from Chinese and Russian national interest

National interest

The national interest, often referred to by the French expression raison d'État , is a country's goals and ambitions whether economic, military, or cultural. The concept is an important one in international relations where pursuit of the national interest is the foundation of the realist...

s, and from the régimes' respective interpretations

Interpretation (logic)

An interpretation is an assignment of meaning to the symbols of a formal language. Many formal languages used in mathematics, logic, and theoretical computer science are defined in solely syntactic terms, and as such do not have any meaning until they are given some interpretation...

of Marxism

Marxism

Marxism is an economic and sociopolitical worldview and method of socioeconomic inquiry that centers upon a materialist interpretation of history, a dialectical view of social change, and an analysis and critique of the development of capitalism. Marxism was pioneered in the early to mid 19th...

: Maoism

Maoism

Maoism, also known as the Mao Zedong Thought , is claimed by Maoists as an anti-Revisionist form of Marxist communist theory, derived from the teachings of the Chinese political leader Mao Zedong . Developed during the 1950s and 1960s, it was widely applied as the political and military guiding...

and Marxism–Leninism. In the 1950s and the 1960s, ideological debate between the Communist parties of Russia and China also concerned the possibility of peaceful coexistence

Peaceful coexistence

Peaceful coexistence was a theory developed and applied by the Soviet Union at various points during the Cold War in the context of its ostensibly Marxist–Leninist foreign policy and was adopted by Soviet-influenced "Communist states" that they could peacefully coexist with the capitalist bloc...

with the capitalist

Capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system that became dominant in the Western world following the demise of feudalism. There is no consensus on the precise definition nor on how the term should be used as a historical category...

West

Western culture

Western culture, sometimes equated with Western civilization or European civilization, refers to cultures of European origin and is used very broadly to refer to a heritage of social norms, ethical values, traditional customs, religious beliefs, political systems, and specific artifacts and...

. Yet, to the Chinese public, Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong, also transliterated as Mao Tse-tung , and commonly referred to as Chairman Mao , was a Chinese Communist revolutionary, guerrilla warfare strategist, Marxist political philosopher, and leader of the Chinese Revolution...

proposed a belligerent attitude towards capitalist

Capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system that became dominant in the Western world following the demise of feudalism. There is no consensus on the precise definition nor on how the term should be used as a historical category...

countries, an initial rejection of peaceful coexistence, which he perceived as Marxist revisionism from the Russian Soviet Union. Moreover, since 1956, the PRC and the USSR had (secretly) diverged about Marxist ideology, and, by 1961, when the doctrinal differences proved intractable, the Communist Party of China

Communist Party of China

The Communist Party of China , also known as the Chinese Communist Party , is the founding and ruling political party of the People's Republic of China...

formally denounced the Soviet variety of Communism

Communism

Communism is a social, political and economic ideology that aims at the establishment of a classless, moneyless, revolutionary and stateless socialist society structured upon common ownership of the means of production...

as a product of “The Revisionist Traitor Group of Soviet Leadership”, the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union was the only legal, ruling political party in the Soviet Union and one of the largest communist organizations in the world...

, headed by Nikita Krushchev.

Origins

The ideological roots of the Sino-Soviet split originated in the 1940s, when the Communist Party of ChinaCommunist Party of China

The Communist Party of China , also known as the Chinese Communist Party , is the founding and ruling political party of the People's Republic of China...

(CCP), led by Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong, also transliterated as Mao Tse-tung , and commonly referred to as Chairman Mao , was a Chinese Communist revolutionary, guerrilla warfare strategist, Marxist political philosopher, and leader of the Chinese Revolution...

, fought the Second Sino-Japanese War

Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War was a military conflict fought primarily between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. From 1937 to 1941, China fought Japan with some economic help from Germany , the Soviet Union and the United States...

(1939–45) against the Empire of Japan

Empire of Japan

The Empire of Japan is the name of the state of Japan that existed from the Meiji Restoration on 3 January 1868 to the enactment of the post-World War II Constitution of...

, whilst simultaneously fighting the Chinese Civil War

Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was a civil war fought between the Kuomintang , the governing party of the Republic of China, and the Communist Party of China , for the control of China which eventually led to China's division into two Chinas, Republic of China and People's Republic of...

against the Nationalist Kuomintang

Kuomintang

The Kuomintang of China , sometimes romanized as Guomindang via the Pinyin transcription system or GMD for short, and translated as the Chinese Nationalist Party is a founding and ruling political party of the Republic of China . Its guiding ideology is the Three Principles of the People, espoused...

, led by Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek was a political and military leader of 20th century China. He is known as Jiǎng Jièshí or Jiǎng Zhōngzhèng in Mandarin....

. In fighting the over-lapping wars, Mao ignored much of the politico-military advice and direction from Joseph Stalin

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

and the Comintern

Comintern

The Communist International, abbreviated as Comintern, also known as the Third International, was an international communist organization initiated in Moscow during March 1919...

, because of the practical difficulty in applying traditional Leninist

Leninism

In Marxist philosophy, Leninism is the body of political theory for the democratic organisation of a revolutionary vanguard party, and the achievement of a direct-democracy dictatorship of the proletariat, as political prelude to the establishment of socialism...

revolutionary theory to China, because there were only peasants, and no urban working class

Working class

Working class is a term used in the social sciences and in ordinary conversation to describe those employed in lower tier jobs , often extending to those in unemployment or otherwise possessing below-average incomes...

, as in Russia.

During the Second World War

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

(1939–45) Stalin had urged Mao into a joint, anti-Japanese coalition with Chiang. After the war, Stalin advised Mao against seizing power, and to negotiate with Chiang, because Stalin had signed a Treaty of Friendship and Alliance with the Nationalists in mid-1945; Mao followed Stalin's lead, calling him “the only leader of our party”. Unwisely, Chiang Kai-Shek opposed USSR’s accession of Tannu Uriankhai

Tannu Uriankhai

Tannu Uriankhai is a historic region of the Mongol Empire and, later, the Qing Dynasty. The realms of Tannu Uriankhai largely correspond to the Tuva Republic of the Russian Federation, neighboring areas in Russia, and a part of the modern state of Mongolia....

, a former Qing Empire province; Stalin broke the treaty requiring Soviet withdrawal from Manchuria three months after Japan’s surrender, and gave Manchuria to Mao. Soon afterwards, a two-month Moscow

Moscow

Moscow is the capital, the most populous city, and the most populous federal subject of Russia. The city is a major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation centre of Russia and the continent...

visit by Mao culminated in the Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship and Alliance (1950), which comprised a $300 million low-interest loan and a 30-year military alliance.

Anna Louise Strong

Anna Louise Strong was a twentieth-century American journalist and activist, best known for her reporting on and support for communist movements in the Soviet Union and the People's Republic of China.-Early years:...

documents, directing her to “show them to Party leaders in the United States and Europe”, but he did not think it was “necessary to take them to Moscow”. Earlier, she had written the article “The Thought of Mao Tse-Tung” and the book Dawn Out of China, reporting that his intellectual accomplishment was “to change Marxism from a European to an Asiatic form... in ways of which neither Marx

Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx was a German philosopher, economist, sociologist, historian, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. His ideas played a significant role in the development of social science and the socialist political movement...

nor Lenin

Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Lenin was a Russian Marxist revolutionary and communist politician who led the October Revolution of 1917. As leader of the Bolsheviks, he headed the Soviet state during its initial years , as it fought to establish control of Russia in the Russian Civil War and worked to create a...

could dream”, which the Soviet government banned in the USSR. Years later, at the first international Communist conclave in Beijing, Mao advocate Liu Shaoqi

Liu Shaoqi

Liu Shaoqi was a Chinese revolutionary, statesman, and theorist. He was Chairman of the People's Republic of China, China's head of state, from 27 April 1959 to 31 October 1968, during which he implemented policies of economic reconstruction in China...

praised the “Mao Tse-tung road” as the correct road to communist revolution, warning it was incorrect to follow any other road; moreover, he praised neither Stalin nor the Soviet communist model, as had been the practice among Communists. Yet, with political and military tensions at crisis in the Korean Peninsula, and a fear of US military intervention there, geopolitical circumstances disallowed the USSR and China any ideological split, hence their alliance continued.

During the 1950s, Soviet-guided China followed the Soviet model of centralized economic development, emphasising heavy industry

Heavy industry

Heavy industry does not have a single fixed meaning as compared to light industry. It can mean production of products which are either heavy in weight or in the processes leading to their production. In general, it is a popular term used within the name of many Japanese and Korean firms, meaning...

, and delegating consumer goods to secondary priority; however, by the late 1950s, Mao had developed different ideas for how China could directly advance to the communist stage of Socialism (per the Marxist denotation), through the mobilization of China’s workers. These ideas progressed to the Great Leap Forward

Great Leap Forward

The Great Leap Forward of the People's Republic of China was an economic and social campaign of the Communist Party of China , reflected in planning decisions from 1958 to 1961, which aimed to use China's vast population to rapidly transform the country from an agrarian economy into a modern...

(1958–61).

After Joseph Stalin’s death in 1953 there was a temporary revival of Sino-Soviet friendship; thus, in 1954, the Soviets calmed Mao with an official visit by Premier Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev led the Soviet Union during part of the Cold War. He served as First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964, and as Chairman of the Council of Ministers, or Premier, from 1958 to 1964...

that featured the formal hand-over of the Lüshun (Port Arthur) naval base to China. The Soviets provided technical aid in 156 industries in China’s first five-year plan, and 520 million rubles in loans; thus at the Geneva Conference of 1954, the PRC and the USSR jointly persuaded the Democratic Republic of Vietnam

North Vietnam

The Democratic Republic of Vietnam , was a communist state that ruled the northern half of Vietnam from 1954 until 1976 following the Geneva Conference and laid claim to all of Vietnam from 1945 to 1954 during the First Indochina War, during which they controlled pockets of territory throughout...

, led by Ho Chi Minh

Ho Chi Minh

Hồ Chí Minh , born Nguyễn Sinh Cung and also known as Nguyễn Ái Quốc, was a Vietnamese Marxist-Leninist revolutionary leader who was prime minister and president of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam...

, to temporarily accept the West’s division of Vietnam

Vietnam

Vietnam – sometimes spelled Viet Nam , officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam – is the easternmost country on the Indochina Peninsula in Southeast Asia. It is bordered by China to the north, Laos to the northwest, Cambodia to the southwest, and the South China Sea –...

at the 17th parallel north

17th parallel north

The 17th parallel north is a circle of latitude that is 17 degrees north of the Earth's equatorial plane. It crosses Africa, Asia, the Indian Ocean, the Pacific Ocean, Central America, the Caribbean and the Atlantic Ocean....

.

Premier Khrushchev’s post-Stalin policies began to irritate Mao; disagreeing when Khruschev denounced Stalin with On the Personality Cult and its Consequences

On the Personality Cult and its Consequences

On the Personality Cult and its Consequences was a report, critical of Joseph Stalin, made to the Twentieth Party Congress on February 25, 1956 by Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev. It is more commonly known as the Secret Speech or the Khrushchev Report...

speech to the Twentieth Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union was the only legal, ruling political party in the Soviet Union and one of the largest communist organizations in the world...

in 1956; and when he restored relations with Yugoslavia

Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia

The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia was the Yugoslav state that existed from the abolition of the Yugoslav monarchy until it was dissolved in 1992 amid the Yugoslav Wars. It was a socialist state and a federation made up of six socialist republics: Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia,...

, led by Josip Broz Tito

Josip Broz Tito

Marshal Josip Broz Tito – 4 May 1980) was a Yugoslav revolutionary and statesman. While his presidency has been criticized as authoritarian, Tito was a popular public figure both in Yugoslavia and abroad, viewed as a unifying symbol for the nations of the Yugoslav federation...

, whom Stalin had denounced

Tito-Stalin Split

The Tito–Stalin Split was a conflict between the leaders of Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, which resulted in Yugoslavia's expulsion from the Communist Information Bureau in 1948...

in 1948. These occurrences shocked Mao, who had supported Stalin ideologically and politically, because Khrushchev was dismantling Mao’s support of the USSR with public rejections of most of Stalin’s leadership and actions — such as announcing the end of the Cominform

Cominform

Founded in 1947, Cominform is the common name for what was officially referred to as the Information Bureau of the Communist and Workers' Parties...

, and (most troubling to Mao), de-emphasising the core Marxist-Leninist thesis of inevitable war between capitalism

Capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system that became dominant in the Western world following the demise of feudalism. There is no consensus on the precise definition nor on how the term should be used as a historical category...

and socialism

Socialism

Socialism is an economic system characterized by social ownership of the means of production and cooperative management of the economy; or a political philosophy advocating such a system. "Social ownership" may refer to any one of, or a combination of, the following: cooperative enterprises,...

. Resultantly, contradicting Stalin, Khrushchev was advocating the idea of “Peaceful Coexistence

Peaceful coexistence

Peaceful coexistence was a theory developed and applied by the Soviet Union at various points during the Cold War in the context of its ostensibly Marxist–Leninist foreign policy and was adopted by Soviet-influenced "Communist states" that they could peacefully coexist with the capitalist bloc...

”, between communist and capitalist nations — which directly challenged Mao’s “lean-to-one-side” foreign policy, adopted after the Chinese Civil War, when he feared direct Japanese or US military intervention, the circumstances that pragmatically required a PRC–Soviet alliance. In de-Stalinizing the USSR, Khrushchev was dissolving the condition that had made the Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship (1950) attractive to China. Mao thought that the Soviets were retreating ideologically and militarily — from Marxism-Leninism and the global struggle to achieve global communism

Communism

Communism is a social, political and economic ideology that aims at the establishment of a classless, moneyless, revolutionary and stateless socialist society structured upon common ownership of the means of production...

, and by apparently no longer guaranteeing support to China in a Sino-American war; therefore, the roots of the Sino-Soviet ideological split were established by 1959.

Onset

Western world

The Western world, also known as the West and the Occident , is a term referring to the countries of Western Europe , the countries of the Americas, as well all countries of Northern and Central Europe, Australia and New Zealand...

in the Cold War. Moreover, the USSR was astonished by the Great Leap Forward

Great Leap Forward

The Great Leap Forward of the People's Republic of China was an economic and social campaign of the Communist Party of China , reflected in planning decisions from 1958 to 1961, which aimed to use China's vast population to rapidly transform the country from an agrarian economy into a modern...

, had renounced aiding Chinese nuclear weapon

Nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission or a combination of fission and fusion. Both reactions release vast quantities of energy from relatively small amounts of matter. The first fission bomb test released the same amount...

s development, and refused to side with them in the Sino-Indian War

Sino-Indian War

The Sino-Indian War , also known as the Sino-Indian Border Conflict , was a war between China and India that occurred in 1962. A disputed Himalayan border was the main pretext for war, but other issues played a role. There had been a series of violent border incidents after the 1959 Tibetan...

(1962), by maintaining a moderate relation with India

India

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

— actions deemed offensive by Mao as Chinese Leader. Hence, he perceived Khrushchev as too-appeasing with the West, despite Soviet caution in international politics that threatened nuclear warfare

Nuclear warfare

Nuclear warfare, or atomic warfare, is a military conflict or political strategy in which nuclear weaponry is detonated on an opponent. Compared to conventional warfare, nuclear warfare can be vastly more destructive in range and extent of damage...

(i.e., the US, UK and USSR were nuclear powers by the late 1950s), wherein the USSR managed superpower confrontations such as the status of post-war Berlin

Berlin

Berlin is the capital city of Germany and is one of the 16 states of Germany. With a population of 3.45 million people, Berlin is Germany's largest city. It is the second most populous city proper and the seventh most populous urban area in the European Union...

.

At first, the Sino-Soviet split manifested itself indirectly; arguments between the CPSU and the CPC criticized the client states of the other; China denounced Yugoslavia and Tito, the USSR denounced Enver Hoxha

Enver Hoxha

Enver Halil Hoxha was a Marxist–Leninist revolutionary andthe leader of Albania from the end of World War II until his death in 1985, as the First Secretary of the Party of Labour of Albania...

and the People's Socialist Republic of Albania

People's Socialist Republic of Albania

The People's Republic of Albania was the official name of Albania during the communist rule between 1946 and 1976. The 1976 Constitution changed the name into People's Socialist Republic of Albania , which was the official name of the country from 1976 until 1991.-Consolidation of power and...

; but, in 1960, they criticized each other in the Romanian Communist Party

Romanian Communist Party

The Romanian Communist Party was a communist political party in Romania. Successor to the Bolshevik wing of the Socialist Party of Romania, it gave ideological endorsement to communist revolution and the disestablishment of Greater Romania. The PCR was a minor and illegal grouping for much of the...

congress, when Khrushchev and Peng Zhen

Peng Zhen

Peng Zhen was a leading member of the Communist Party of China.-Biography:Born in Houma , Peng was originally named Fu Maogong....

openly argued. Premier Khrushchev insulted Chairman Mao Zedong as “a nationalist, an adventurist, and a deviationist”. In turn, Mao insulted Khrushchev as a Marxist revisionist, criticizing him as “patriarchal, arbitrary and tyrannical”. In follow-up, Khrushchev denounced China with an eighty-page letter to the conference.

Khrushchev also withdrew nearly all Soviet technical experts from China, leaving some major projects in an unfinished state. Many blueprints and specifications were also withdrawn.

In November 1960, at a congress of 81 Communist parties in Moscow, the Chinese argued with the Soviets and with most other Communist party delegations — yet compromised to avoid a formal ideologic splitting; nonetheless, in October 1961, at the 22nd Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union they again argued openly. In December, the USSR severed diplomatic relations with the People’s Socialist Republic of Albania, graduating the Soviet–Chinese ideological dispute from between political parties to between nation-states.

In 1962, the PRC and the USSR broke relations because of their international actions; Chairman Mao criticized Premier Khrushchev for withdrawing from fighting the US in the Cuban missile crisis

Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis was a confrontation among the Soviet Union, Cuba and the United States in October 1962, during the Cold War...

(1962) — “Khrushchev has moved from adventurism to capitulationism”; Khrushchev replied that Mao’s confrontational policies would provoke a nuclear war

Nuclear warfare

Nuclear warfare, or atomic warfare, is a military conflict or political strategy in which nuclear weaponry is detonated on an opponent. Compared to conventional warfare, nuclear warfare can be vastly more destructive in range and extent of damage...

. Simultaneously, the USSR sided with India against China in the Sino-Indian War

Sino-Indian War

The Sino-Indian War , also known as the Sino-Indian Border Conflict , was a war between China and India that occurred in 1962. A disputed Himalayan border was the main pretext for war, but other issues played a role. There had been a series of violent border incidents after the 1959 Tibetan...

(1962). Each régime followed these actions with formal ideological statements; in June 1963, the PRC published The Chinese Communist Party’s Proposal Concerning the General Line of the International Communist Movement http://www.etext.org/Politics/MIM/classics/mao/polemics/index.html, and the USSR replied with an Open Letter of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union; http://web.archive.org/web/20071225024740/www.etext.org/Politics/MIM/classics/mao/polemics/sevenlet.html these were the final, formal communications between the two Communist parties. Furthermore, by 1964, Chairman Mao asserted that a counter-revolution in the USSR had re-established capitalism

Capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system that became dominant in the Western world following the demise of feudalism. There is no consensus on the precise definition nor on how the term should be used as a historical category...

there; consequently, the Chinese and Soviet Communist parties broke relations, and the Warsaw Pact

Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Treaty Organization of Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance , or more commonly referred to as the Warsaw Pact, was a mutual defense treaty subscribed to by eight communist states in Eastern Europe...

Communist parties followed Soviet suit.

After Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev – 10 November 1982) was the General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union , presiding over the country from 1964 until his death in 1982. His eighteen-year term as General Secretary was second only to that of Joseph Stalin in...

deposed Premier Khrushchev in October 1964, the Chinese Prime Minister Zhou Enlai

Zhou Enlai

Zhou Enlai was the first Premier of the People's Republic of China, serving from October 1949 until his death in January 1976...

travelled to Moscow, in November, to speak with the new leaders of the USSR, Brezhnev and Alexei Kosygin, but returned disappointed to China, reporting to Mao that the Soviets remained firm; undeterred, Chairman Mao denounced “Khrushchevism without Khrushchev”, continuing the polemical.

From words to war

The tripolar Cold War

In the mid–1960s, when the People’s Republic of China openly competed against the USSR to be the international leader of the CommunistCommunism

Communism is a social, political and economic ideology that aims at the establishment of a classless, moneyless, revolutionary and stateless socialist society structured upon common ownership of the means of production...

and Socialist

Socialism

Socialism is an economic system characterized by social ownership of the means of production and cooperative management of the economy; or a political philosophy advocating such a system. "Social ownership" may refer to any one of, or a combination of, the following: cooperative enterprises,...

countries, the Sino–Soviet split imbalanced the 1945 bipolar configuration of the Cold War

Cold War

The Cold War was the continuing state from roughly 1946 to 1991 of political conflict, military tension, proxy wars, and economic competition between the Communist World—primarily the Soviet Union and its satellite states and allies—and the powers of the Western world, primarily the United States...

as an ideologic competition exclusively between the U.S. and the USSR; the inter-communist rivalry transformed the Cold War into a tripolar geopolitical

Geopolitics

Geopolitics, from Greek Γη and Πολιτική in broad terms, is a theory that describes the relation between politics and territory whether on local or international scale....

contest.

The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution

Meanwhile, in China, Mao Zedong launched the Cultural RevolutionCultural Revolution

The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, commonly known as the Cultural Revolution , was a socio-political movement that took place in the People's Republic of China from 1966 through 1976...

(1966–76) to rid himself of internal enemies and re-establish his sole leadership of party and country; and to prevent the development of Russian-style bureaucratic communism of the USSR. He closed the schools and universities and organized the students in the Red Guard, a thought police

Thought Police

The Thought Police is the secret police of Oceania in George Orwell's dystopian novel Nineteen Eighty-Four.It is the job of the Thought Police to uncover and punish thoughtcrime and thought-criminals, using psychology and omnipresent surveillance from telescreens to monitor, search, find and kill...

politically commissioned to discover, denounce, and persecute teachers, intellectuals

Intellectualism

Intellectualism denotes the use and development of the intellect, the practice of being an intellectual, and of holding intellectual pursuits in great regard. Moreover, in philosophy, “intellectualism” occasionally is synonymous with “rationalism”, i.e. knowledge derived mostly from reason and...

, and government officials who might be counter-revolutionaries and secret bourgeois, all of which enforced the cult of personality

Cult of personality

A cult of personality arises when an individual uses mass media, propaganda, or other methods, to create an idealized and heroic public image, often through unquestioning flattery and praise. Cults of personality are usually associated with dictatorships...

of Chairman Mao. In purging the enemies of the state from Chinese society, the Red Guard divided into factions, and their subsequent violence provoked civil war in some parts of China; Mao had the Army suppress the Red Guard factions; and when factionalism occurred in the Army, Mao dispersed the Red Guard, and then began to rebuild the Chinese Communist Party.

The political house-cleaning that was the Cultural Revolution stressed, strained, and broke China’s political relations with the USSR, and relations with the West

Western world

The Western world, also known as the West and the Occident , is a term referring to the countries of Western Europe , the countries of the Americas, as well all countries of Northern and Central Europe, Australia and New Zealand...

. Nevertheless, despite the “Maoism vs. Marxism–Leninism” differences interpreting Marxism

Marxism

Marxism is an economic and sociopolitical worldview and method of socioeconomic inquiry that centers upon a materialist interpretation of history, a dialectical view of social change, and an analysis and critique of the development of capitalism. Marxism was pioneered in the early to mid 19th...

, Russia and China aided North Vietnam

North Vietnam

The Democratic Republic of Vietnam , was a communist state that ruled the northern half of Vietnam from 1954 until 1976 following the Geneva Conference and laid claim to all of Vietnam from 1945 to 1954 during the First Indochina War, during which they controlled pockets of territory throughout...

, headed by Ho Chi Minh

Ho Chi Minh

Hồ Chí Minh , born Nguyễn Sinh Cung and also known as Nguyễn Ái Quốc, was a Vietnamese Marxist-Leninist revolutionary leader who was prime minister and president of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam...

, in fighting the Vietnam War

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War was a Cold War-era military conflict that occurred in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. This war followed the First Indochina War and was fought between North Vietnam, supported by its communist allies, and the government of...

(1945–75), which Maoism

Maoism

Maoism, also known as the Mao Zedong Thought , is claimed by Maoists as an anti-Revisionist form of Marxist communist theory, derived from the teachings of the Chinese political leader Mao Zedong . Developed during the 1950s and 1960s, it was widely applied as the political and military guiding...

defined as a peasant revolution against foreign imperialism

Imperialism

Imperialism, as defined by Dictionary of Human Geography, is "the creation and/or maintenance of an unequal economic, cultural, and territorial relationships, usually between states and often in the form of an empire, based on domination and subordination." The imperialism of the last 500 years,...

. The Chinese allowed Soviet matériel across China for the North, to prosecute the war against the Republic of Vietnam

South Vietnam

South Vietnam was a state which governed southern Vietnam until 1975. It received international recognition in 1950 as the "State of Vietnam" and later as the "Republic of Vietnam" . Its capital was Saigon...

, a U.S. client state. In that time, besides the Socialist People's Republic of Albania, only the Communist Party of Indonesia

Communist Party of Indonesia

The Communist Party of Indonesia was the largest non-ruling communist party in the world prior to being crushed in 1965 and banned the following year.-Forerunners:...

advocated the Maoist

Maoism

Maoism, also known as the Mao Zedong Thought , is claimed by Maoists as an anti-Revisionist form of Marxist communist theory, derived from the teachings of the Chinese political leader Mao Zedong . Developed during the 1950s and 1960s, it was widely applied as the political and military guiding...

policy of peasant revolution.

National interests conflict

Since 1956, the Sino–Soviet ideologicalIdeology

An ideology is a set of ideas that constitutes one's goals, expectations, and actions. An ideology can be thought of as a comprehensive vision, as a way of looking at things , as in common sense and several philosophical tendencies , or a set of ideas proposed by the dominant class of a society to...

split, between Communist political parties, had escalated to small-scale warfare between Russia and China; thereby, in January 1967, Red Guards

Red Guards (China)

Red Guards were a mass movement of civilians, mostly students and other young people in the People's Republic of China , who were mobilized by Mao Zedong in 1966 and 1967, during the Cultural Revolution.-Origins:...

attacked the Soviet embassy in Beijing. Earlier, in 1966, the Chinese had revived the matter of the Russo-Chinese border that was demarcated in the 19th-century, and imposed upon the Qing Dynasty

Qing Dynasty

The Qing Dynasty was the last dynasty of China, ruling from 1644 to 1912 with a brief, abortive restoration in 1917. It was preceded by the Ming Dynasty and followed by the Republic of China....

(1644–1912) monarchy by means of unequal treaties that virtually annexed Chinese territory to Tsarist Russia. Despite not asking the return of territory, the Chinese did ask the USSR to formally (publicly) acknowledge that said border, established with the Treaty of Aigun

Treaty of Aigun

The Treaty of Aigun was a 1858 treaty between the Russian Empire, and the empire of the Qing Dynasty, the sinicized-Manchu rulers of China, that established much of the modern border between the Russian Far East and Manchuria , which is now known as Northeast China...

(1858) and the Convention of Peking

Convention of Peking

The Convention of Peking or the First Convention of Peking is the name used for three different unequal treaties, which were concluded between Qing China and the United Kingdom, France, and Russia.-Background:...

(1860), was an historic Russian injustice against China; the Soviet government ignored the matter. Then, in 1968, the Red Guard purge

Purge

In history, religion, and political science, a purge is the removal of people who are considered undesirable by those in power from a government, from another organization, or from society as a whole. Purges can be peaceful or violent; many will end with the imprisonment or exile of those purged,...

s meant to restore doctrinal orthodoxy

Orthodoxy

The word orthodox, from Greek orthos + doxa , is generally used to mean the adherence to accepted norms, more specifically to creeds, especially in religion...

to China had provoked civil war in parts of the country, which Mao resolved with the People's Liberation Army

People's Liberation Army

The People's Liberation Army is the unified military organization of all land, sea, strategic missile and air forces of the People's Republic of China. The PLA was established on August 1, 1927 — celebrated annually as "PLA Day" — as the military arm of the Communist Party of China...

suppressing the pertinent cohorts of the Red Guard; the excesses of the Red Guard and of the Cultural Revolution declined. Mao required internal political equilibrium in order to protect China from the strategic and military vulnerabilities that resulted from its political isolation from the community of nations.

Border war

Meanwhile, during 1968, the Soviet ArmySoviet Army

The Soviet Army is the name given to the main part of the Armed Forces of the Soviet Union between 1946 and 1992. Previously, it had been known as the Red Army. Informally, Армия referred to all the MOD armed forces, except, in some cases, the Soviet Navy.This article covers the Soviet Ground...

had amassed along the 4,380 km (2,738 mi.) border with China — especially at the Xinjiang

Xinjiang

Xinjiang is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China. It is the largest Chinese administrative division and spans over 1.6 million km2...

frontier, in north-west China, where the Soviets might readily induce Turkic

Turkic peoples

The Turkic peoples are peoples residing in northern, central and western Asia, southern Siberia and northwestern China and parts of eastern Europe. They speak languages belonging to the Turkic language family. They share, to varying degrees, certain cultural traits and historical backgrounds...

separatists to insurrection. Militarily, in 1961, the USSR had 12 divisions and 200 aeroplanes at that border; in 1968, there were 25 divisions, 1,200 aeroplanes, and 120 medium-range missiles. Moreover, although China had exploded its first nuclear weapon

596 (nuclear test)

596 is the codename of the People's Republic of China's first nuclear weapons test, detonated on October 16, 1964 at the Lop Nur test site. It was a uranium-235 implosion fission device and had a yield of 22 kilotons...

(the 596 Test), in October 1964, at Lop Nur

Lop Nur

Lop Lake or Lop Nur is a group of small, now seasonal salt lake sand marshes between the Taklamakan and Kuruktag deserts in the Bayingolin Mongol Autonomous Prefecture, southeastern portion of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region in the People's Republic of China.The lake system into which the Tarim...

basin, the People's Liberation Army

People's Liberation Army

The People's Liberation Army is the unified military organization of all land, sea, strategic missile and air forces of the People's Republic of China. The PLA was established on August 1, 1927 — celebrated annually as "PLA Day" — as the military arm of the Communist Party of China...

was militarily inferior to the Soviet Army. By March 1969, Sino–Russian border politics became the Sino-Soviet border conflict

Sino-Soviet border conflict

The Sino–Soviet border conflict was a seven-month military conflict between the Soviet Union and China at the height of the Sino–Soviet split in 1969. The most serious of these border clashes occurred in March 1969 in the vicinity of Zhenbao Island on the Ussuri River, also known as Damanskii...

at the Ussuri River

Sino-Soviet border conflict

The Sino–Soviet border conflict was a seven-month military conflict between the Soviet Union and China at the height of the Sino–Soviet split in 1969. The most serious of these border clashes occurred in March 1969 in the vicinity of Zhenbao Island on the Ussuri River, also known as Damanskii...

and on Damansky–Zhenbao Island; more small-scale warfare occurred at Tielieketi

Tielieketi

Tielieketi is a part of Yumin County in Xinjiang, the People's Republic of China, adjacent to the border with Kazakhstan.-Tielieketi Incident:...

in August. In The Coming War Between Russia and China (1969), US journalist Harrison Salisbury

Harrison Salisbury

Harrison Evans Salisbury , an American Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist , was the first regular New York Times correspondent in Moscow after World War II. He was born in Minneapolis, Minnesota...

reported that Soviet sources implied a possible first strike

First strike

In nuclear strategy, a first strike is a preemptive surprise attack employing overwhelming force. First strike capability is a country's ability to defeat another nuclear power by destroying its arsenal to the point where the attacking country can survive the weakened retaliation while the opposing...

against the Lop Nur

Lop Nur

Lop Lake or Lop Nur is a group of small, now seasonal salt lake sand marshes between the Taklamakan and Kuruktag deserts in the Bayingolin Mongol Autonomous Prefecture, southeastern portion of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region in the People's Republic of China.The lake system into which the Tarim...

basin nuclear weapons testing site. The U.S. warned the USSR that a nuclear attack against China would precipitate a world-wide war; the USSR relented. Aware of that possibility, China built large-scale underground shelters, such as Beijing’s Underground City

Underground City (Beijing)

The Underground City , also known as Dixia Cheng, is a bomb shelter comprising a network of tunnels located beneath Beijing, China, which has since been transformed into a tourist attraction. It has been called the Underground Great Wall because it was built for the purpose of military defense...

, and military shelters such as the Underground Project 131

Underground Project 131

Underground Project 131 is a system of tunnels in China's Hubei province constructed in the late 1960s and the early 1970s to accommodate the Chinese military command headquarters in case of a nuclear war...

command center, in Hubei

Hubei

' Hupeh) is a province in Central China. The name of the province means "north of the lake", referring to its position north of Lake Dongting...

, and the "816 Project" nuclear research center in Fuling

Fuling District

Fuling District is a district in the middle of Chongqing Municipality, People's Republic of China. Its name means "Fu Cemetery" because some rulers of the State of Ba were originally buried there....

, Chongqing

Chongqing

Chongqing is a major city in Southwest China and one of the five national central cities of China. Administratively, it is one of the PRC's four direct-controlled municipalities , and the only such municipality in inland China.The municipality was created on 14 March 1997, succeeding the...

.

Geopolitical pragmatism

In 1969, after the Sino-Soviet border conflictSino-Soviet border conflict

The Sino–Soviet border conflict was a seven-month military conflict between the Soviet Union and China at the height of the Sino–Soviet split in 1969. The most serious of these border clashes occurred in March 1969 in the vicinity of Zhenbao Island on the Ussuri River, also known as Damanskii...

, the Communist combatants withdrew. In September, Soviet Minister Alexei Kosygin secretly visited Beijing to speak with Premier Zhou Enlai

Zhou Enlai

Zhou Enlai was the first Premier of the People's Republic of China, serving from October 1949 until his death in January 1976...

, and in October, the PRC and the USSR began discussing border-demarcation. Although they did not resolve the border demarcation matters, the meetings restored diplomatic communications; by 1970, Mao understood that the PRC could not simultaneously fight the USSR and the USA, whilst suppressing internal disorder. Moreover, as the Vietnam War

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War was a Cold War-era military conflict that occurred in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. This war followed the First Indochina War and was fought between North Vietnam, supported by its communist allies, and the government of...

continued, and Chinese anti-American rhetoric continued, Mao perceived the USSR as the greater threat, and thus pragmatically sought rapprochement with the US, in confronting the USSR. In July 1971, U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger

Henry Kissinger

Heinz Alfred "Henry" Kissinger is a German-born American academic, political scientist, diplomat, and businessman. He is a recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize. He served as National Security Advisor and later concurrently as Secretary of State in the administrations of Presidents Richard Nixon and...

secretly visited Beijing to prepare the February 1972 head-of-state visit to China by U.S. President Richard Nixon

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon was the 37th President of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. The only president to resign the office, Nixon had previously served as a US representative and senator from California and as the 36th Vice President of the United States from 1953 to 1961 under...

. Moreover, the diplomatically offended Soviet Union also convoked a summit meeting with President Nixon, thus establishing the Washington–Beijing–Moscow diplomatic relationship, which emphasized the tripolar nature of the Cold War, occasioned by the ideological Sino–Soviet split begun in 1956.

Concerning the 4,380 km (2,738 mi.) Sino–Soviet border, Soviet counter-propaganda advertised against the PRC’s drawing attention to the unequal Treaty of Aigun

Treaty of Aigun

The Treaty of Aigun was a 1858 treaty between the Russian Empire, and the empire of the Qing Dynasty, the sinicized-Manchu rulers of China, that established much of the modern border between the Russian Far East and Manchuria , which is now known as Northeast China...

(1858) and the Convention of Peking

Convention of Peking

The Convention of Peking or the First Convention of Peking is the name used for three different unequal treaties, which were concluded between Qing China and the United Kingdom, France, and Russia.-Background:...

(1860). Moreover, between 1972 and 1973, the USSR deleted the Chinese and Manchu place-names — Iman (伊曼, Yiman), Tetyukhe (from 野猪河, yĕzhūhé), and Suchan — from the Soviet Far East map, and replaced them with the Russian place-names Dalnerechensk

Dalnerechensk

Dalnerechensk is a town in Primorsky Krai, Russia. Population: It was originally known as Iman , but its Russian name was changed to Dalnerechensk in 1972, as part of a general campaign of asserting Soviet sovereignty in the region...

, Dalnegorsk

Dalnegorsk

Dalnegorsk is a town in Primorsky Krai, Russia. Population: It was formerly known from its founding in 1899 as Tetyukhe , until it was renamed in 1972 as part of a campaign to change any Chinese-derived placenames in the Primorsky Krai.-History:...

, and Partizansk

Partizansk

Partizansk is a town in Primorsky Krai, Russia, located on a spur of the Sikhote-Alin mountains, about east of Vladivostok. Population: The town was formerly known as Suchan and Gamarnik.-Geography:...

. In the Stalinist

Stalinism

Stalinism refers to the ideology that Joseph Stalin conceived and implemented in the Soviet Union, and is generally considered a branch of Marxist–Leninist ideology but considered by some historians to be a significant deviation from this philosophy...

tradition, the pre–1860 Chinese presence in lands Tsarist Russia acquired with, the Treaty of Aigun and the Convention of Peking, became a politically incorrect

Political correctness

Political correctness is a term which denotes language, ideas, policies, and behavior seen as seeking to minimize social and institutional offense in occupational, gender, racial, cultural, sexual orientation, certain other religions, beliefs or ideologies, disability, and age-related contexts,...

subject in the Soviet press, “inconvenient” museum exhibits were removed from public view, and the Jurchen-script

Jurchen script

Jurchen script was the writing system used to write Jurchen language, the language of the Jurchen people who created the Jin Empire in the northeastern China of the 12th–13th centuries. It was derived from the Khitan script, which in turn was derived from Chinese...

text about the Jin Dynasty stele

Stele

A stele , also stela , is a stone or wooden slab, generally taller than it is wide, erected for funerals or commemorative purposes, most usually decorated with the names and titles of the deceased or living — inscribed, carved in relief , or painted onto the slab...

, supported by a stone tortoise

Bixi (tortoise)

Bixi , also called guifu or baxia , is a stone tortoise, used as a pedestal for a stele or tablet. Tortoise-mounted stelae have been traditionally used in the funerary complexes of Chinese emperors and other dignitaries. Later, they have also been used to commemorate an important event, such as...

in the Khabarovsk

Khabarovsk

Khabarovsk is the largest city and the administrative center of Khabarovsk Krai, Russia. It is located some from the Chinese border. It is the second largest city in the Russian Far East, after Vladivostok. The city became the administrative center of the Far Eastern Federal District of Russia...

Museum, was covered with cement.

International Communist rivalry

In the 1970s, Sino–Soviet ideological rivalry extended to AfricaAfrica

Africa is the world's second largest and second most populous continent, after Asia. At about 30.2 million km² including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of the Earth's total surface area and 20.4% of the total land area...

and the Middle East

Middle East

The Middle East is a region that encompasses Western Asia and Northern Africa. It is often used as a synonym for Near East, in opposition to Far East...

, where the Soviet Union and Red China funded and supported opposed political parties, militias, and states, notably the Ogaden War

Ogaden War

The Ogaden War was a conventional conflict between Somalia and Ethiopia in 1977 and 1978 over the Ogaden region of Ethiopia. In a notable illustration of the nature of Cold War alliances, the Soviet Union switched from supplying aid to Somalia to supporting Ethiopia, which had previously been...

(1977–1978) between Ethiopia and Somalia, the Rhodesian Bush War

Rhodesian Bush War

The Rhodesian Bush War – also known as the Second Chimurenga or the Zimbabwe War of Liberation – was a civil war which took place between July 1964 and December 1979 in the unrecognised country of Rhodesia...

(1964–1979), the Zimbabwean Gukurahundi

Gukurahundi

The Gukurahundi refers to the suppression by Zimbabwe's 5th Brigade in the predominantly Ndebele regions of Zimbabwe most of whom were supporters of Joshua Nkomo. A few hundred disgruntled former ZIPRA combatants waged armed banditry against the civilians in Matabeleland, and destroyed government...

(1980–1987), the Angolan Civil War

Angolan Civil War

The Angolan Civil War was a major civil conflict in the Southern African state of Angola, beginning in 1975 and continuing, with some interludes, until 2002. The war began immediately after Angola became independent from Portugal in November 1975. Prior to this, a decolonisation conflict had taken...

(1975–2002), the Mozambican Civil War

Mozambican Civil War