Euthyphro

Encyclopedia

Euthyphro is one of Plato

's early dialogues, dated to after 399 BC. Taking place during the weeks leading up to Socrates

' trial, the dialogue features Socrates and Euthyphro, a man known for claiming to be a religious expert. They attempt to pinpoint a definition for piety

.

's court, where the two men encounter each other. They are both there for preliminary hearings before possible trials (2a).

Euthyphro has come to lay manslaughter charges against his father, as his father had allowed one of his workers to die exposed to the elements without proper care and attention (3e–4d). This worker had killed a slave belonging to the family estate on the island of Naxos; while Euthyphro's father waited to hear from the expounders of religious law (exegetes cf. Laws 759d) about how to proceed, the worker died bound and gagged in a ditch. Socrates expresses his astonishment at the confidence of a man able to take his own father to court on such a serious charge, even when Athenian Law allows only relatives of the deceased to sue for murder (Dem. 43 § 57). Euthyphro misses the astonishment, and merely confirms his overconfidence in his own judgment of religious/ethical matters. In an example of "Socratic irony," Socrates states that Euthyphro obviously has a clear understanding of what is pious (τὸ ὅσιον to hosion) and impious (τὸ ἀνόσιον to anosion). Since Socrates himself is facing a charge of impiety, he expresses the hope to learn from Euthyphro, all the better to defend himself in his own trial.

Euthyphro claims that what lies behind the charge brought against Socrates by Meletus

and the other accusers is Socrates' claim that he is subjected to a daimon

or divine sign which warns him of various courses of action (3b). Even more suspicious from the viewpoint of many Athenians, Socrates expresses skeptical views on the main stories about the Greek gods, which the two men briefly discuss before plunging into the main argument. Socrates expresses reservations about such accounts which show up the gods' cruelty and inconsistency. He mentions the castration of the early sky god, Uranus

, by his son Cronus

, saying he finds such stories very difficult to accept (6a–6c).

Yet after claiming to be able to tell even more amazing such stories, Euthyphro spends little time or effort defending the conventional view of the gods. Instead, he is led straight to the real task at hand, as Socrates forces him to confront his ignorance, ever pressing him for a definition of 'piety'. Yet with every definition Euthyphro proposes, Socrates very quickly finds a fatal flaw (6d ff.).

At the end of the dialogue, Euthyphro is forced to admit that each definition has been a failure, but rather than correct it, he makes the excuse that it is time for him to go, and Socrates ends the dialogue with a classic example of Socratic irony: since Euthyphro has been unable to come up with a definition that will stand on its own two feet, Euthyphro has failed to teach Socrates anything at all about piety, and so he has received no aid for his own defense at his own trial (15c ff.).

The argument of this dialog is based largely on "definition by division". Socrates goads Euthyphro to offer one definition after another for the word 'piety'. The hope is to use a clear definition as the basis for Euthyphro to teach Socrates the answer to the question, "What is piety?", ostensibly so that Socrates can use this to defend himself against the charge of impiety.

The argument of this dialog is based largely on "definition by division". Socrates goads Euthyphro to offer one definition after another for the word 'piety'. The hope is to use a clear definition as the basis for Euthyphro to teach Socrates the answer to the question, "What is piety?", ostensibly so that Socrates can use this to defend himself against the charge of impiety.

It is clear that Socrates wants a definition of piety that will be universally true (i.e., a ‘universal’), against which all actions can be measured to determine whether or not they are pious. It is equally clear that to be a universal, the definition must express what is essential about the thing defined, and be in terms of genus, species, and its differentiae (this terminology is somewhat later than Socrates, made more famous with Aristotle).

Hence this dialogue is important not just for theology

, ethics

, and epistemology, but even for metaphysics. Indeed: Plato's approach here has been accused of being too overtly anachronistic, since it is highly unlikely that Socrates himself was such a "master metaphysician". But the more expository treatment of metaphysics we find in Aristotle has its roots in the Platonic dialogues, especially in the Euthyphro.

The stages of the argument can be summarised as follows:

characteristic which makes pious things pious.

should be punished, but Socrates argues that disputes would still arise — over just how much justification there actually was, and hence the same action could still be both pious and impious. So yet again, Euthyphro's 'definition' cannot possibly be a definition.

" by asking the crucial question: "Is the pious loved by the gods because it is pious? Or is it pious because it is loved by the gods (10a)?" This is where he sets up his typical dialectic

. This Socratic technique, essentially an analogy

or comparison in this instance, is used to make his question clearer. He gets Euthyphro to agree that we call a carried thing "carried" simply because it is carried, not because it possesses some inherent characteristic

or property that we could call "carried". That is, being carried is not an essential characteristic of the thing carried; being carried is a state. Likewise with piety, if defined as "what is liked by the gods"; it is liked for some reason, not just because it is liked, so that one likes it, by itself, does not make an action pious. The liking must follow from recognition that an action is pious, not the other way around. Thus the piety comes before the liking both temporally and logically, yet in Euthyphro's definition it is exactly the other way around. Therefore Euthyphro's third definition is severely flawed.

To the modern reader, this part of the argument (10a-11a) sounds painfully convoluted. But it had to be written this way, because there was no standard term at that time for such grammatical entities as "passive voice". Socrates cannot simplify his explanation by using the term "passive voice". Nor can he refer to Aristotle's Categories, which also goes into great detail on this distinction (treating it as between simple expressions of state and secondary substances). So he explains with detailed examples ('carried', 'loved', 'seen') instead.

Without yet realizing that it makes his definition circular, Euthyphro at this point agrees that the gods like an action because it is pious. Socrates argues that the unanimous approval of the gods is merely an attribute of piety; it is not part of its defining characteristics. It does not define the essence of piety, what piety is in itself; it does not give the idea of piety, so it cannot be a universal definition of 'piety.'

However, as he then points out a little later, this is still not enough for a definition, since piety belongs to those actions we call just

or morally good. However, there are more than simply pious actions that we call just or morally good (12d); for example, bravery, concern for others and so on. What is it, asks Socrates, that makes piety different from all those other actions that we call just? We cannot say something is simply because we believe it to be so. We must find proof.

, which gods frowned upon (13c). Euthyphro claims that caring for involves service. When questioned by Socrates as to exactly what is the end product of piety, Euthyphro can only fall back on his earlier claim: piety is what is loved by all the gods (14b).

, esteem and favor

" (15a). In other words, as he admits, piety is intimately bound up with what the gods like. The discussion has come full circle. Euthyphro rushes off to another engagement, and Socrates faces a preliminary hearing on the charge of impiety.

Plato

Plato , was a Classical Greek philosopher, mathematician, student of Socrates, writer of philosophical dialogues, and founder of the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. Along with his mentor, Socrates, and his student, Aristotle, Plato helped to lay the...

's early dialogues, dated to after 399 BC. Taking place during the weeks leading up to Socrates

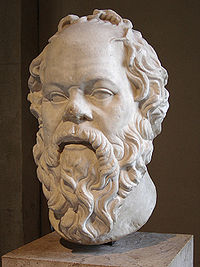

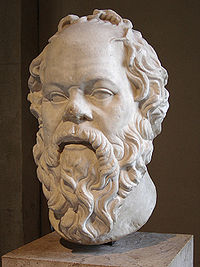

Socrates

Socrates was a classical Greek Athenian philosopher. Credited as one of the founders of Western philosophy, he is an enigmatic figure known chiefly through the accounts of later classical writers, especially the writings of his students Plato and Xenophon, and the plays of his contemporary ...

' trial, the dialogue features Socrates and Euthyphro, a man known for claiming to be a religious expert. They attempt to pinpoint a definition for piety

Piety

In spiritual terminology, piety is a virtue that can mean religious devotion, spirituality, or a combination of both. A common element in most conceptions of piety is humility.- Etymology :...

.

Background

The dialogue is set near the king-archonArchon basileus

Archon Basileus was a Greek title, meaning 'king magistrate': the term is derived the words archon "magistrate" and basileus "king" or "sovereign"....

's court, where the two men encounter each other. They are both there for preliminary hearings before possible trials (2a).

Euthyphro has come to lay manslaughter charges against his father, as his father had allowed one of his workers to die exposed to the elements without proper care and attention (3e–4d). This worker had killed a slave belonging to the family estate on the island of Naxos; while Euthyphro's father waited to hear from the expounders of religious law (exegetes cf. Laws 759d) about how to proceed, the worker died bound and gagged in a ditch. Socrates expresses his astonishment at the confidence of a man able to take his own father to court on such a serious charge, even when Athenian Law allows only relatives of the deceased to sue for murder (Dem. 43 § 57). Euthyphro misses the astonishment, and merely confirms his overconfidence in his own judgment of religious/ethical matters. In an example of "Socratic irony," Socrates states that Euthyphro obviously has a clear understanding of what is pious (τὸ ὅσιον to hosion) and impious (τὸ ἀνόσιον to anosion). Since Socrates himself is facing a charge of impiety, he expresses the hope to learn from Euthyphro, all the better to defend himself in his own trial.

Euthyphro claims that what lies behind the charge brought against Socrates by Meletus

Meletus

The Apology of Socrates by Plato names Meletus as the chief accuser of Socrates. He is also mentioned in the Euthyphro. Given his awkwardness as an orator, and his likely age at the time of Socrates' death, many hold that he was not the real leader of the movement against the early philosopher,...

and the other accusers is Socrates' claim that he is subjected to a daimon

Daimon

Daimon is an Ancient Greek word referring to lesser supernatural beings, including minor gods and the spirits of dead heroes.It may also refer to:- People :* Daimon Shelton , professional American football player...

or divine sign which warns him of various courses of action (3b). Even more suspicious from the viewpoint of many Athenians, Socrates expresses skeptical views on the main stories about the Greek gods, which the two men briefly discuss before plunging into the main argument. Socrates expresses reservations about such accounts which show up the gods' cruelty and inconsistency. He mentions the castration of the early sky god, Uranus

Uranus (mythology)

Uranus , was the primal Greek god personifying the sky. His equivalent in Roman mythology was Caelus. In Ancient Greek literature, according to Hesiod in his Theogony, Uranus or Father Sky was the son and husband of Gaia, Mother Earth...

, by his son Cronus

Cronus

In Greek mythology, Cronus or Kronos was the leader and the youngest of the first generation of Titans, divine descendants of Gaia, the earth, and Uranus, the sky...

, saying he finds such stories very difficult to accept (6a–6c).

Yet after claiming to be able to tell even more amazing such stories, Euthyphro spends little time or effort defending the conventional view of the gods. Instead, he is led straight to the real task at hand, as Socrates forces him to confront his ignorance, ever pressing him for a definition of 'piety'. Yet with every definition Euthyphro proposes, Socrates very quickly finds a fatal flaw (6d ff.).

At the end of the dialogue, Euthyphro is forced to admit that each definition has been a failure, but rather than correct it, he makes the excuse that it is time for him to go, and Socrates ends the dialogue with a classic example of Socratic irony: since Euthyphro has been unable to come up with a definition that will stand on its own two feet, Euthyphro has failed to teach Socrates anything at all about piety, and so he has received no aid for his own defense at his own trial (15c ff.).

The argument

It is clear that Socrates wants a definition of piety that will be universally true (i.e., a ‘universal’), against which all actions can be measured to determine whether or not they are pious. It is equally clear that to be a universal, the definition must express what is essential about the thing defined, and be in terms of genus, species, and its differentiae (this terminology is somewhat later than Socrates, made more famous with Aristotle).

Hence this dialogue is important not just for theology

Theology

Theology is the systematic and rational study of religion and its influences and of the nature of religious truths, or the learned profession acquired by completing specialized training in religious studies, usually at a university or school of divinity or seminary.-Definition:Augustine of Hippo...

, ethics

Ethics

Ethics, also known as moral philosophy, is a branch of philosophy that addresses questions about morality—that is, concepts such as good and evil, right and wrong, virtue and vice, justice and crime, etc.Major branches of ethics include:...

, and epistemology, but even for metaphysics. Indeed: Plato's approach here has been accused of being too overtly anachronistic, since it is highly unlikely that Socrates himself was such a "master metaphysician". But the more expository treatment of metaphysics we find in Aristotle has its roots in the Platonic dialogues, especially in the Euthyphro.

The stages of the argument can be summarised as follows:

First definition

Euthyphro offers as his first definition of piety what he is doing now, that is, prosecuting his father for manslaughter (5d). Socrates rejects this because it is not a definition; it is only an example or instance of piety. It does not provide the fundamentalFundamental

Fundamental may refer to:* Foundation of reality* Fundamental frequency, as in music or phonetics, often referred to as simply a "fundamental"...

characteristic which makes pious things pious.

Second definition

Euthyphro's second definition: piety is what is pleasing to the gods (6e-7a). Socrates applauds this definition because it is expressed in a general form, but criticizes it on the grounds that the gods disagree among themselves as to what is 'pleasing'. This would mean that a particular action, disputed by the gods, would be both pious and impious at the same time — a logically impossible situation. Euthyphro tries to argue against Socrates' criticism by pointing out that not even the gods would disagree amongst themselves that someone who kills without justificationJustification (jurisprudence)

Justification in jurisprudence is an exception to the prohibition of committing certain offenses. Justification can be a defense in a prosecution for a criminal offense. When an act is justified, a person is not criminally liable even though his act would otherwise constitute an offense. For...

should be punished, but Socrates argues that disputes would still arise — over just how much justification there actually was, and hence the same action could still be both pious and impious. So yet again, Euthyphro's 'definition' cannot possibly be a definition.

Third definition

Euthyphro attempts to overcome Socrates' objection by slightly amending his second definition (9e). Thus the third definition reads: What all the gods love is pious, and what they all hate is impious. At this point Socrates introduces the "Euthyphro dilemmaEuthyphro dilemma

The Euthyphro dilemma is found in Plato's dialogue Euthyphro, in which Socrates asks Euthyphro: "Is the pious loved by the gods because it is pious, or is it pious because it is loved by the gods?"...

" by asking the crucial question: "Is the pious loved by the gods because it is pious? Or is it pious because it is loved by the gods (10a)?" This is where he sets up his typical dialectic

Dialectic

Dialectic is a method of argument for resolving disagreement that has been central to Indic and European philosophy since antiquity. The word dialectic originated in Ancient Greece, and was made popular by Plato in the Socratic dialogues...

. This Socratic technique, essentially an analogy

Analogy

Analogy is a cognitive process of transferring information or meaning from a particular subject to another particular subject , and a linguistic expression corresponding to such a process...

or comparison in this instance, is used to make his question clearer. He gets Euthyphro to agree that we call a carried thing "carried" simply because it is carried, not because it possesses some inherent characteristic

Characteristic

Characteristic may refer to:In physics and engineering, any characteristic curve that shows the relationship between certain input and output parameters, for example:...

or property that we could call "carried". That is, being carried is not an essential characteristic of the thing carried; being carried is a state. Likewise with piety, if defined as "what is liked by the gods"; it is liked for some reason, not just because it is liked, so that one likes it, by itself, does not make an action pious. The liking must follow from recognition that an action is pious, not the other way around. Thus the piety comes before the liking both temporally and logically, yet in Euthyphro's definition it is exactly the other way around. Therefore Euthyphro's third definition is severely flawed.

To the modern reader, this part of the argument (10a-11a) sounds painfully convoluted. But it had to be written this way, because there was no standard term at that time for such grammatical entities as "passive voice". Socrates cannot simplify his explanation by using the term "passive voice". Nor can he refer to Aristotle's Categories, which also goes into great detail on this distinction (treating it as between simple expressions of state and secondary substances). So he explains with detailed examples ('carried', 'loved', 'seen') instead.

Without yet realizing that it makes his definition circular, Euthyphro at this point agrees that the gods like an action because it is pious. Socrates argues that the unanimous approval of the gods is merely an attribute of piety; it is not part of its defining characteristics. It does not define the essence of piety, what piety is in itself; it does not give the idea of piety, so it cannot be a universal definition of 'piety.'

Fourth definition

In the second half of the discussion Socrates himself suggests a definition of piety (12d), namely that "piety is a species of the genus 'justice'". But he leads up to this with both observations and questions concerning the difference between species and genus, starting with:...are you not compelled to think that all that is pious is just?

However, as he then points out a little later, this is still not enough for a definition, since piety belongs to those actions we call just

Justice

Justice is a concept of moral rightness based on ethics, rationality, law, natural law, religion, or equity, along with the punishment of the breach of said ethics; justice is the act of being just and/or fair.-Concept of justice:...

or morally good. However, there are more than simply pious actions that we call just or morally good (12d); for example, bravery, concern for others and so on. What is it, asks Socrates, that makes piety different from all those other actions that we call just? We cannot say something is simply because we believe it to be so. We must find proof.

Euthyphro's response

Euthyphro then suggests that piety is concerned with looking after the gods (13b), but Socrates immediately raises the objection that "looking after", if used in its ordinary sense, which Euthyphro agrees that it is, would imply that when you perform an act of piety you make one of the gods better — a dangerous example of hubrisHubris

Hubris , also hybris, means extreme haughtiness, pride or arrogance. Hubris often indicates a loss of contact with reality and an overestimation of one's own competence or capabilities, especially when the person exhibiting it is in a position of power....

, which gods frowned upon (13c). Euthyphro claims that caring for involves service. When questioned by Socrates as to exactly what is the end product of piety, Euthyphro can only fall back on his earlier claim: piety is what is loved by all the gods (14b).

Final definition

Euthyphro then proposes yet again another definition: Piety, he says, is an art of sacrifice and prayer. He puts forward the notion of piety as a form of knowledge of how to do exchange: giving the gods gifts, and asking favours of them in turn (14e). Socrates presses Euthyphro to state what benefit the gods get from the gifts humans give to them, warning that this "knowledge of exchange" is a species of commerce (14e). Euthyphro objects that the gifts are not that sort of gift at all, but rather "honourHonour

Honour or honor is an abstract concept entailing a perceived quality of worthiness and respectability that affects both the social standing and the self-evaluation of an individual or corporate body such as a family, school, regiment or nation...

, esteem and favor

Favor

Favor, Favour, or Favors, may refer to:* Favor , a deed in which help is voluntarily provided* Party favor, a small gift given to the guests at a party...

" (15a). In other words, as he admits, piety is intimately bound up with what the gods like. The discussion has come full circle. Euthyphro rushes off to another engagement, and Socrates faces a preliminary hearing on the charge of impiety.

Literature

- R.E. Allen: Plato's "Euthyphro" and the Earlier Theory of Forms. London 1970, ISBN 0710067283.

See also

- Divine command theoryDivine command theoryDivine command theory is the meta-ethical view about the semantics or meaning of ethical sentences, which claims that ethical sentences express propositions, some of which are true, about the attitudes of God...

- Euthyphro dilemmaEuthyphro dilemmaThe Euthyphro dilemma is found in Plato's dialogue Euthyphro, in which Socrates asks Euthyphro: "Is the pious loved by the gods because it is pious, or is it pious because it is loved by the gods?"...

- DialecticDialecticDialectic is a method of argument for resolving disagreement that has been central to Indic and European philosophy since antiquity. The word dialectic originated in Ancient Greece, and was made popular by Plato in the Socratic dialogues...

- Socratic dialogues