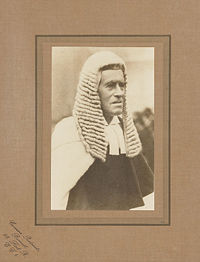

Frank Douglas MacKinnon

Encyclopedia

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

lawyer

Lawyer

A lawyer, according to Black's Law Dictionary, is "a person learned in the law; as an attorney, counsel or solicitor; a person who is practicing law." Law is the system of rules of conduct established by the sovereign government of a society to correct wrongs, maintain the stability of political...

, judge

Judge

A judge is a person who presides over court proceedings, either alone or as part of a panel of judges. The powers, functions, method of appointment, discipline, and training of judges vary widely across different jurisdictions. The judge is supposed to conduct the trial impartially and in an open...

and writer

Writer

A writer is a person who produces literature, such as novels, short stories, plays, screenplays, poetry, or other literary art. Skilled writers are able to use language to portray ideas and images....

, the only High Court judge

High Court judge

A High Court judge is a judge of the High Court of Justice, and represents the third highest level of judge in the courts of England and Wales. High Court judges are referred to as puisne judges...

to be appointed during the First Labour Government.

Early life and legal practice

Born in HighgateHighgate

Highgate is an area of North London on the north-eastern corner of Hampstead Heath.Highgate is one of the most expensive London suburbs in which to live. It has an active conservation body, the Highgate Society, to protect its character....

, London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

, the eldest son of 7 children of Benjamin Thomas, a Lloyd's

Lloyd's of London

Lloyd's, also known as Lloyd's of London, is a British insurance and reinsurance market. It serves as a partially mutualised marketplace where multiple financial backers, underwriters, or members, whether individuals or corporations, come together to pool and spread risk...

underwriter and Katherine née Edwards, he attended Highgate School

Highgate School

-Notable members of staff and governing body:* John Ireton, brother of Henry Ireton, Cromwellian General* 1st Earl of Mansfield, Lord Chief Justice, owner of Kenwood, noted for judgment finding contracts for slavery unenforceable in English law* T. S...

and Trinity College, Oxford

Trinity College, Oxford

The College of the Holy and Undivided Trinity in the University of Oxford, of the foundation of Sir Thomas Pope , or Trinity College for short, is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England. It stands on Broad Street, next door to Balliol College and Blackwells bookshop,...

, graduating in classics

Classics

Classics is the branch of the Humanities comprising the languages, literature, philosophy, history, art, archaeology and other culture of the ancient Mediterranean world ; especially Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome during Classical Antiquity Classics (sometimes encompassing Classical Studies or...

(1892) and literae humaniores

Literae Humaniores

Literae Humaniores is the name given to an undergraduate course focused on Classics at Oxford and some other universities.The Latin name means literally "more humane letters", but is perhaps better rendered as "Advanced Studies", since humaniores has the sense of "more refined" or "more learned",...

(1894). MacKinnon was called to the bar by the Inner Temple

Inner Temple

The Honourable Society of the Inner Temple, commonly known as Inner Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court in London. To be called to the Bar and practise as a barrister in England and Wales, an individual must belong to one of these Inns...

in 1897 and became a pupil

Pupillage

A pupillage, in England and Wales, Northern Ireland and Ireland, is the barrister's equivalent of the training contract that a solicitor undertakes...

of Thomas Edward Scrutton

Thomas Edward Scrutton

Sir Thomas Edward Scrutton was an English legal text-writer and judge.-Biography:Thomas Edward Scrutton was born in London, UK. He studied as a scholar at Trinity College, Cambridge, then at University College London...

where he was a contemporary of James Richard Atkin, later to become Lord Atkin. When Scrutton became a QC

Queen's Counsel

Queen's Counsel , known as King's Counsel during the reign of a male sovereign, are lawyers appointed by letters patent to be one of Her [or His] Majesty's Counsel learned in the law...

in 1901, MacKinnon benefited from Scrutton's former junior practice in commercial law

Commercial law

Commercial law is the body of law that governs business and commercial transactions...

. MacKinnon's brother, Sir Percy Graham MacKinnon

Percy Graham MacKinnon

Sir Percy Graham MacKinnon was born in Highgate, London, the second son of 7 children of Benjamin Thomas, a Lloyd's underwriter and Katherine née Edwards. He followed his father into Lloyd's, and became chairman no less than 5 times...

(1872–1956) was, from time to time, chairman of Lloyd's and his family connections helped build his practice.

MacKinnon married Frances Massey in 1906 and the couple had two children. He became a KC in 1914 and found the circumstances of World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

led him to an extensive practice in prize law

Prize (law)

Prize is a term used in admiralty law to refer to equipment, vehicles, vessels, and cargo captured during armed conflict. The most common use of prize in this sense is the capture of an enemy ship and its cargo as a prize of war. In the past, it was common that the capturing force would be allotted...

. The war also generated many complex contract

Contract

A contract is an agreement entered into by two parties or more with the intention of creating a legal obligation, which may have elements in writing. Contracts can be made orally. The remedy for breach of contract can be "damages" or compensation of money. In equity, the remedy can be specific...

ual disputes and MacKinnon developed a reputation for handling such cases with skill. Many issues such as frustration of contract attracted his attention and his pen.

He began to establish a reputation as a jurist

Jurist

A jurist or jurisconsult is a professional who studies, develops, applies, or otherwise deals with the law. The term is widely used in American English, but in the United Kingdom and many Commonwealth countries it has only historical and specialist usage...

and to advise the government on mercantile law, especially its international dimension.

High Court judge

In October 1924, the minority Labour government was suffering the repercussions of the Campbell caseCampbell Case

The Campbell Case of 1924 involved charges against a British Communist newspaper editor for alleged "incitement to mutiny" caused by his publication of a provocative open letter to members of the military...

and was not expected to survive. When Sir Clement Bailhache

Clement Bailhache

Sir Clement Meacher Bailhache was an English commercial lawyer and judge.Born Leeds, the eldest son of parents of Huguenot descent, his father, Rev Clement Bailache was a Baptist minister, secretary of the Baptist Missionary Society, his mother, Emma né Meacher...

died, Lord Chancellor

Lord Chancellor

The Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, or Lord Chancellor, is a senior and important functionary in the government of the United Kingdom. He is the second highest ranking of the Great Officers of State, ranking only after the Lord High Steward. The Lord Chancellor is appointed by the Sovereign...

Richard Haldane, 1st Viscount Haldane

Richard Haldane, 1st Viscount Haldane

Richard Burdon Haldane, 1st Viscount Haldane KT, OM, PC, KC, FRS, FBA, FSA , was an influential British Liberal Imperialist and later Labour politician, lawyer and philosopher. He was Secretary of State for War between 1905 and 1912 during which time the "Haldane Reforms" were implemented...

was anxious that the appointment of a High Court judge

High Court judge

A High Court judge is a judge of the High Court of Justice, and represents the third highest level of judge in the courts of England and Wales. High Court judges are referred to as puisne judges...

was not made "in the last agony of the government's existence". The appointment was made in some haste.

MacKinnon sat in the Commercial Court but also went on circuit with the assizes

Assizes

Assize or Assizes may refer to:Assize or Assizes may refer to:Assize or Assizes may refer to::;in common law countries :::*assizes , an obsolete judicial inquest...

. Criminal law

Criminal law

Criminal law, is the body of law that relates to crime. It might be defined as the body of rules that defines conduct that is not allowed because it is held to threaten, harm or endanger the safety and welfare of people, and that sets out the punishment to be imposed on people who do not obey...

and juries had never formed a material part of his practice but he adapted well though his reputation as a judge never matched his standing as a lawyer.

In 1926, he chaired a committee to review the law on arbitration

Arbitration

Arbitration, a form of alternative dispute resolution , is a legal technique for the resolution of disputes outside the courts, where the parties to a dispute refer it to one or more persons , by whose decision they agree to be bound...

. The committee concluded that the Arbitration Act 1889 had been effective and recommended only some miscellaneous amendments. The recommendations were only parted impemented in the Arbitration Acts of 1928 and 1934.

Lord Justice of Appeal

In 1937, MacKinnon was elevated to the Court of AppealCourt of Appeal of England and Wales

The Court of Appeal of England and Wales is the second most senior court in the English legal system, with only the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom above it...

and sworn in to the Privy Council. A pragmatist, he may have had a greater impact had he not felt so impatient as to never reserve judgment. He was considered for the House of Lords

Lord of Appeal in Ordinary

Lords of Appeal in Ordinary, commonly known as Law Lords, were appointed under the Appellate Jurisdiction Act 1876 to the House of Lords of the United Kingdom in order to exercise its judicial functions, which included acting as the highest court of appeal for most domestic matters...

in 1938 but Samuel Porter, Baron Porter

Samuel Porter, Baron Porter

Samuel Lowry Porter, Baron Porter was a British judge.On 28 March 1938, he was appointed Lord of Appeal in Ordinary and created a life peer with the title Baron Porter, of Longfield in County Tyrone. A month later, he was invested to the Privy Council. Porter resigned as Lord of Appeal in...

was preferred.

He was one of those judges who, on occasion, causes amusement through their unfamiliarity with popular culture

Popular culture

Popular culture is the totality of ideas, perspectives, attitudes, memes, images and other phenomena that are deemed preferred per an informal consensus within the mainstream of a given culture, especially Western culture of the early to mid 20th century and the emerging global mainstream of the...

. In a notorious libel trial in 1943, the court was viewing a photograph from the magazine Lilliput

Lilliput (magazine)

Lilliput was a small-format British monthly magazine of humour, short stories, photographs and the arts, founded in 1937 by the photojournalist Stefan Lorant. The first issue came out in July and it was sold shortly after to Edward Hulton, when editorship was taken over by Tom Hopkinson in 1940....

showing a well-known male fashion designer juxtaposed next to a pansy

Pansy

The Pansy is a large group of hybrid plants cultivated as garden flowers. Pansies are derived from Viola species Viola tricolor hybridized with other viola species, these hybrids are referred to as Viola × wittrockiana or less commonly Viola tricolor hortensis...

. MacKinnon had to ask Rayner Goddard, Baron Goddard

Rayner Goddard, Baron Goddard

Rayner Goddard, Baron Goddard was Lord Chief Justice of England from 1946 to 1958 and known for his strict sentencing and conservative views. He was nicknamed the 'Tiger' and "Justice-in-a-jiffy" for his no-nonsense manner...

to explain the innuendo

Innuendo

An innuendo is a baseless invention of thoughts or ideas. It can also be a remark or question, typically disparaging , that works obliquely by allusion...

. Towards the end of his life he confessed to neither owning nor intending to own a "wiresless set

Radio

Radio is the transmission of signals through free space by modulation of electromagnetic waves with frequencies below those of visible light. Electromagnetic radiation travels by means of oscillating electromagnetic fields that pass through the air and the vacuum of space...

".

He also gained some notoriety for doubting the grounds of the leading negligence

Negligence

Negligence is a failure to exercise the care that a reasonably prudent person would exercise in like circumstances. The area of tort law known as negligence involves harm caused by carelessness, not intentional harm.According to Jay M...

case of Donoghue v. Stevenson

Donoghue v. Stevenson

Donoghue v Stevenson [1932] UKHL 100 was a decision of the House of Lords that established the modern concept of negligence in Scots law and English law, by setting out general principles whereby one person would owe another person a duty of care...

. About the case, which involved a snail

Snail

Snail is a common name applied to most of the members of the molluscan class Gastropoda that have coiled shells in the adult stage. When the word is used in its most general sense, it includes sea snails, land snails and freshwater snails. The word snail without any qualifier is however more often...

in a bottle of mineral water

Mineral water

Mineral water is water containing minerals or other dissolved substances that alter its taste or give it therapeutic value, generally obtained from a naturally occurring mineral spring or source. Dissolved substances in the water may include various salts and sulfur compounds...

, MacKinninon said, in his 1942 Holdsworth lecture:

Lord Normand

Wilfrid Normand, Baron Normand

Wilfrid Guild Normand, Baron Normand, KC, PC , was a Scottish politician and judge.Educated at Fettes College, Edinburgh, Oriel College, Oxford, Paris University and Edinburgh University, he was admitted as an advocate in 1910. He served in the Royal Engineers from 1915 to 1918...

, the defendant's advocate

Faculty of Advocates

The Faculty of Advocates is an independent body of lawyers who have been admitted to practise as advocates before the courts of Scotland, especially the Court of Session and the High Court of Justiciary...

, always insisted that MacKinnon's allegation was untrue.

Trials as judge

- Shirlaw v. Southern Foundries (1926) Ltd [1939] 2 KB 206 - in which he defined the "officious bystander test" for implied contractual termContractual termA contractual term is "Any provision forming part of a contract" Each term gives rise to a contractual obligation, breach of which can give rise to litigation. Not all terms are stated expressly and some terms carry less legal gravity as they are peripheral to the objectives of the...

s. - Salisbury (Marquess) v. Gilmore [1942] - in which Tom Denning KC attempted to argue that the doctrine of estoppelEstoppelEstoppel in its broadest sense is a legal term referring to a series of legal and equitable doctrines that preclude "a person from denying or asserting anything to the contrary of that which has, in contemplation of law, been established as the truth, either by the acts of judicial or legislative...

should be extended to promises rather than solely statements of fact. MacKinnon rejected the argument but Denning had his way once he himself was a High Court judge in Central London Property Trust Ltd v. High Trees House LtdCentral London Property Trust Ltd v. High Trees House LtdCentral London Property Trust Ltd v High Trees House Ltd [1947] KB 130 is an English contract law decision in the High Court. It reaffirmed the doctrine of promissory estoppel in contract law in England and Wales...

(1947). - R v. Home Secretary, ex parte Greene [1942] 1 KB 87 - sitting with Lords Justice of Appeal ScottLeslie Scott (UK politician)Sir Leslie Frederic Scott, KC, PC was a Conservative Party politician in the United Kingdom, and later a senior judge....

and GoddardRayner Goddard, Baron GoddardRayner Goddard, Baron Goddard was Lord Chief Justice of England from 1946 to 1958 and known for his strict sentencing and conservative views. He was nicknamed the 'Tiger' and "Justice-in-a-jiffy" for his no-nonsense manner...

, the court rejected Ben GreeneBen GreeneBen Greene was a British Labour Party politician and pacifist. He was interned during World War II because of his fascist associations and appealed his detention to the House of Lords. In the leading case of Liversidge v...

's application for a writWritIn common law, a writ is a formal written order issued by a body with administrative or judicial jurisdiction; in modern usage, this body is generally a court...

of habeas corpusHabeas corpusis a writ, or legal action, through which a prisoner can be released from unlawful detention. The remedy can be sought by the prisoner or by another person coming to his aid. Habeas corpus originated in the English legal system, but it is now available in many nations...

to review his detention under Defence Regulation 18BDefence Regulation 18BDefence Regulation 18B, often referred to as simply 18B, was the most famous of the Defence Regulations used by the British Government during World War II. The complete technical reference name for this rule was: Regulation 18B of the Defence Regulations 1939. It allowed for the internment of...

. The court ruled that is could not question the discretion of the Home Secretary, honestly exercised. Greene appealed to the House of LordsHouse of LordsThe House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster....

who, in Liversidge v. AndersonLiversidge v. AndersonLiversidge v Anderson [1942] AC 206 is an important and landmark case in English law which concerned the relationship between the courts and the state, and in particular the assistance that the judiciary should give to the executive in times of national emergency. It concerns civil liberties and...

, confirmed the Court of Appeal's decision

Other interests

MacKinnon was an enthusiast for the writing and culture of the eighteenth century and, in particular, the work of Doctor Johnson. He wrote extensively on the period. He also considered Victorian architectureVictorian architecture

The term Victorian architecture refers collectively to several architectural styles employed predominantly during the middle and late 19th century. The period that it indicates may slightly overlap the actual reign, 20 June 1837 – 22 January 1901, of Queen Victoria. This represents the British and...

to have ruined much of what came before. When the Temple Church

Temple Church

The Temple Church is a late-12th-century church in London located between Fleet Street and the River Thames, built for and by the Knights Templar as their English headquarters. In modern times, two Inns of Court both use the church. It is famous for its effigy tombs and for being a round church...

was bombed during The Blitz

The Blitz

The Blitz was the sustained strategic bombing of Britain by Nazi Germany between 7 September 1940 and 10 May 1941, during the Second World War. The city of London was bombed by the Luftwaffe for 76 consecutive nights and many towns and cities across the country followed...

, he welcomed it with mixed feelings:

Never interested in party politics, MacKinnon was president of the Average Adjusters' Association (1935), of the Johnson Society of Lichfield (1933), and of the Buckinghamshire Archaeological Society, chairman of Buckinghamshire

Buckinghamshire

Buckinghamshire is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan home county in South East England. The county town is Aylesbury, the largest town in the ceremonial county is Milton Keynes and largest town in the non-metropolitan county is High Wycombe....

quarter sessions

Quarter Sessions

The Courts of Quarter Sessions or Quarter Sessions were local courts traditionally held at four set times each year in the United Kingdom and other countries in the former British Empire...

, and member of the Historical Manuscripts Commission.

MacKinnon was a keen walker, climbing Snowdon

Snowdon

Snowdon is the highest mountain in Wales, at an altitude of above sea level, and the highest point in the British Isles outside Scotland. It is located in Snowdonia National Park in Gwynedd, and has been described as "probably the busiest mountain in Britain"...

on two consecutive days in February 1931 when aged almost 60.

Personal

"In appearance MacKinnon possessed bushy eyebrows, penetrating eyes, a pronounced angular nose, and firm mouth." His daughter, son-in-law and young grandchild were lost aboard the Almeda Star, torpedoTorpedo

The modern torpedo is a self-propelled missile weapon with an explosive warhead, launched above or below the water surface, propelled underwater towards a target, and designed to detonate either on contact with it or in proximity to it.The term torpedo was originally employed for...

ed in 1941. His son became bursar

Bursar

A bursar is a senior professional financial administrator in a school or university.Billing of student tuition accounts are the responsibility of the Office of the Bursar. This involves sending bills and making payment plans with the ultimate goal of getting the student accounts paid off...

of Eton College

Eton College

Eton College, often referred to simply as Eton, is a British independent school for boys aged 13 to 18. It was founded in 1440 by King Henry VI as "The King's College of Our Lady of Eton besides Wyndsor"....

. Following a sudden heart attack, he died in Charing Cross Hospital

Charing Cross Hospital

Charing Cross Hospital is a general, acute hospital located in London, United Kingdom and established in 1818. It is located several miles to the west of the city centre in the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham....

.

Honours

- Inner TempleInner TempleThe Honourable Society of the Inner Temple, commonly known as Inner Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court in London. To be called to the Bar and practise as a barrister in England and Wales, an individual must belong to one of these Inns...

:- BencherBencherA bencher or Master of the Bench is a senior member of an Inn of Court in England and Wales. Benchers hold office for life once elected. A bencher can be elected while still a barrister , in recognition of the contribution that the barrister has made to the life of the Inn or to the law...

(1923); - Treasurer (1945);

- Bencher

- KnightKnightA knight was a member of a class of lower nobility in the High Middle Ages.By the Late Middle Ages, the rank had become associated with the ideals of chivalry, a code of conduct for the perfect courtly Christian warrior....

ed (1924); - Honorary fellow of Trinity College, Oxford (1931)

- Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries

By MacKinnon

- MacKinnon, F. D. (1917) Effect of War on Contract

- — (1926) "Some aspects of commercial law"

- — (ed.) (1930) Burney, F.Fanny BurneyFrances Burney , also known as Fanny Burney and, after her marriage, as Madame d’Arblay, was an English novelist, diarist and playwright. She was born in Lynn Regis, now King’s Lynn, England, on 13 June 1752, to musical historian Dr Charles Burney and Mrs Esther Sleepe Burney...

Evelina - — (1933) "The law and the lawyers" in Turberville, A. S. (ed.) Johnson's England: An Account of the Life and Manners of his Age, Oxford: Clarendon Press

- — (1935) The Murder in the Temple and Other Holiday Tasks, London: Sweet & Maxwell

- — (1936) "The origins of commercial law", Law Quarterly Review, 52 30

- — (1937) Grand Larceny

- — (1940) On Circuit: 1924–1937, Camridge: Cambridge University Press

- — (1945a) The Ravages of the War in the Inner Temple

- — (1945b) "An unfortunate preference", Law Quarterly Review, 61 237–8

- — (1948) Inner Temple Papers, London: Stevens & Co.

- — (ed.) [various editions] Scrutton on Charterparties and Bills of Lading

Obituaries

- A. L. GArthur Lehman GoodhartArthur Lehman Goodhart, KBE, KC was an American-born British academic jurist and lawyer; he was professor of jurisprudence, University of Oxford, 1931–51, when he was also a Fellow of University College, Oxford...

(1946) "F. D. M., 1871–1946", Law Quarterly Review, 62 139–40 - The TimesThe TimesThe Times is a British daily national newspaper, first published in London in 1785 under the title The Daily Universal Register . The Times and its sister paper The Sunday Times are published by Times Newspapers Limited, a subsidiary since 1981 of News International...

, 24 Jan 1946

About MacKinnon

- Birkett, N. (1949) "Review of Inner Temple papers, Law Quarterly Review, 65 380–84

- Rubin, G. R. (2004) "MacKinnon, Sir Frank Douglas (1871–1946)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, accessed 2 August 2007