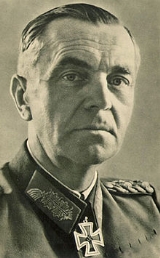

Friedrich Paulus

Encyclopedia

Friedrich Wilhelm Ernst Paulus (23 September 1890 – 1 February 1957) was an officer

in the German

military

from 1910 to 1945. He attained the rank

of Generalfeldmarschall

(field marshal

) during World War II

, and is best known for having commanded the Sixth Army's assault on Stalingrad

during Operation Blue

in 1942. The battle ended in disaster for Nazi Germany

when approximately 270,000 soldiers of the Wehrmacht

, Axis allies and Hilfswillige were encircled and defeated in a massive Soviet

counterattack in November 1942, with casualties reaching as high as 740,000.

Paulus surrendered to Soviet forces in Stalingrad on 31 January 1943, a day after he was promoted to the rank of Generalfeldmarschall by Adolf Hitler

. Hitler expected Paulus to commit suicide, citing the fact that there was no record of a German field marshal ever surrendering to enemy forces. While in Soviet captivity during the war Paulus became a vocal critic of the Nazi regime and joined the Russian-sponsored National Committee for a Free Germany

. He was not released until 1953.

, Hesse-Nassau, the son of a school teacher.

He tried, unsuccessfully, to secure a cadetship in the Kaiserliche Marine

and briefly studied law at Marburg University.

When World War I

began, Paulus's regiment was part of the thrust into France

, and he saw action in the Vosges

and around Arras

in the autumn of 1914. After a leave of absence due to illness, he joined the Alpenkorps

as a staff officer, serving in Macedonia

, France and Serbia

. By the end of the war, he was a captain.

After the Armistice, Paulus fought with the Freikorps

in the east as a brigade adjutant. He remained in the scaled-down Reichswehr

that came into being after the Treaty of Versailles

and was assigned to the 13th Infantry Regiment at Stuttgart

as a company commander. He served in various staff positions for over a decade (1921–1933) and then briefly commanded a motorized battalion (1934–1935) before being named chief of staff for the Panzer

headquarters in October 1935, a new formation under Lutz

that directed the training and development of the army's three panzer divisions.

In February 1938 Paulus was appointed Chef des Generalstabes to Guderian

's new XVI Armeekorps (Motorisiert), which replaced Lutz's command. Guderian described him as ‘brilliantly clever, conscientious, hard working, original and talented’ but already had doubts about his decisiveness, toughness and lack of command experience. He remained in that post until May 1939, when he was promoted to Major General

and became Chief of Staff for the German Tenth Army

, with which he saw service in Poland

, the Netherlands

and Belgium

(by the latter two campaigns, the army had been renumbered as the Sixth Army

).

Paulus was promoted to Lieutenant General

in August 1940 and the following month he was named deputy chief of the German General Staff

(OQu I). In that role he helped draft the plans for the invasion of the Soviet Union

.

Paulus was promoted to General of the Armoured Troops

Paulus was promoted to General of the Armoured Troops

and became commander of the German Sixth Army in January 1942 and led the drive on Stalingrad during that summer. Paulus' troops fought the defending Soviet troops holding Stalingrad over three months in increasingly brutal urban warfare. In November 1942, when the Soviet Red Army

launched a massive counter-offensive, code named Operation Uranus

, Paulus found himself surrounded by an entire Soviet Army Group.

Paulus followed Adolf Hitler

's orders to hold the Army's position in Stalingrad under all circumstances, despite the fact that he was completely surrounded by strong Russian formations. A relief effort by Army Group Don

under Field Marshal Erich von Manstein

failed in December, inevitably: insufficient force was available to challenge the Soviet forces encircling the German 6th Army, and Hitler refused to allow Paulus to break out of Stalingrad despite Manstein telling him it was the only way the effort would succeed. By this time, Paulus' remaining armour had only sufficient fuel for a 12-mile advance anyway. In any event, Paulus was refused permission to break out of the encirclement. Kurt Zeitzler

, the newly appointed chief of the Army General Staff

, eventually got Hitler to allow Paulus to break out—provided they held onto Stalingrad, an impossible task.

For the next two months, Paulus and his men fought on. However, the lack of ammunition, equipment attrition and deteriorating physical condition of the German troops prevented them from defending effectively against the Red Army. The battle was fought with terrible losses on both sides and great suffering.

On 8 January 1943, General Konstantin Rokossovsky

On 8 January 1943, General Konstantin Rokossovsky

, commander of the Red Army on the Don front, called a cease fire and offered Paulus' men generous surrender terms—normal rations, medical treatment for the ill and wounded, permission to retain their badges, decorations, uniforms and personal effects, and repatriation to any country they wished after the war. Rokossovsky also noted that Paulus was in a nearly impossible situation. By this time, there was no hope for Paulus to be relieved or supplied by air, and most of his men had no winter clothing. However, when Paulus asked Hitler for permission to surrender, Hitler rejected this request almost out of hand and ordered him to hold Stalingrad to the last man.

After a heavy Soviet offensive overran the last emergency airstrip in Stalingrad on 25 January, the Russians again offered Paulus a chance to surrender. Once again, Hitler ordered Paulus to hold Stalingrad to the death. On 30 January, Paulus informed Hitler that his men were hours from collapse. Hitler responded by showering a raft of field promotions by radio on Paulus' officers to build up their spirits and steel their will to hold their ground. Most significantly, he promoted Paulus to field marshal. In deciding to promote Paulus, Hitler noted that there was no known record of a Prussia

n or German field marshal ever having surrendered. The implication was clear: Paulus was to commit suicide. If Paulus surrendered, he would shame Germany's military history.

Despite this, and to the disgust of Hitler, Paulus and his staff surrendered the next day, 31 January. On the 2 February 1943 the remainder of the Sixth Army capitulated. Upon finding out about Paulus' surrender, Hitler flew into a rage, and vowed never to appoint another field marshal again, though he would in fact go on to appoint another seven field marshals in his lifetime. Speaking about the surrender of Paulus, Hitler told his staff:

Paulus, a Roman Catholic, was opposed to suicide. During his captivity, according to General Pfeffer

, Paulus said of Hitler's expectation: "I have no intention of shooting myself for this Bohemia

n private

". Another general told the NKVD

that Paulus had told him about his promotion to field marshal and said: "It looks like an invitation to commit suicide, but I will not do this favour for him." Paulus also forbade his soldiers from standing on top of their trenches in order to be shot by the enemy.

of Hitler on 20 July 1944, Paulus became a vocal critic of the Nazi regime while in Soviet captivity, joining the Russian-sponsored National Committee for a Free Germany

and appealing to Germans to surrender. He later acted as a witness for the prosecution at the Nuremberg Trials

. He was released in 1953, two years before the repatriation of the remaining German POWs (mostly other Stalingrad veterans) who had been designated war criminals by the Soviets

. Paulus settled in the German Democratic Republic

(East Germany).

During the Nuremberg Trials, Paulus was asked about the Stalingrad prisoners by a journalist. Paulus told the journalist to tell the wives and mothers that their husbands and sons were well. Of the 91,000 German prisoners taken at Stalingrad, half had died on the march to Siberia

n prison camps, nearly as many died in captivity; only about 6,000 returned home.

From 1953 to 1956, he lived in Dresden

, East Germany, where he worked as the civilian chief of the East German Military History Research Institute and not, as often wrongly described, as an inspector of police. In late 1956, he developed motor neuron disease

and was eventually left paralyzed. He died in Dresden on 1 February 1957, exactly 14 years after he surrendered at Stalingrad. His body was brought for burial in Baden

next to that of his wife, who had died in 1949 having not seen her husband since his surrender.

Officer (armed forces)

An officer is a member of an armed force or uniformed service who holds a position of authority. Commissioned officers derive authority directly from a sovereign power and, as such, hold a commission charging them with the duties and responsibilities of a specific office or position...

in the German

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

military

Military

A military is an organization authorized by its greater society to use lethal force, usually including use of weapons, in defending its country by combating actual or perceived threats. The military may have additional functions of use to its greater society, such as advancing a political agenda e.g...

from 1910 to 1945. He attained the rank

Military rank

Military rank is a system of hierarchical relationships in armed forces or civil institutions organized along military lines. Usually, uniforms denote the bearer's rank by particular insignia affixed to the uniforms...

of Generalfeldmarschall

Generalfeldmarschall

Field Marshal or Generalfeldmarschall in German, was a rank in the armies of several German states and the Holy Roman Empire; in the Austrian Empire, the rank Feldmarschall was used...

(field marshal

Field Marshal

Field Marshal is a military rank. Traditionally, it is the highest military rank in an army.-Etymology:The origin of the rank of field marshal dates to the early Middle Ages, originally meaning the keeper of the king's horses , from the time of the early Frankish kings.-Usage and hierarchical...

) during World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, and is best known for having commanded the Sixth Army's assault on Stalingrad

Battle of Stalingrad

The Battle of Stalingrad was a major battle of World War II in which Nazi Germany and its allies fought the Soviet Union for control of the city of Stalingrad in southwestern Russia. The battle took place between 23 August 1942 and 2 February 1943...

during Operation Blue

Operation Blue

Case Blue , later renamed Operation Braunschweig, was the German Armed Forces name for its plan for a 1942 strategic summer offensive in southern Russia between 28 June and November 1942....

in 1942. The battle ended in disaster for Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

when approximately 270,000 soldiers of the Wehrmacht

Wehrmacht

The Wehrmacht – from , to defend and , the might/power) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the Heer , the Kriegsmarine and the Luftwaffe .-Origin and use of the term:...

, Axis allies and Hilfswillige were encircled and defeated in a massive Soviet

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

counterattack in November 1942, with casualties reaching as high as 740,000.

Paulus surrendered to Soviet forces in Stalingrad on 31 January 1943, a day after he was promoted to the rank of Generalfeldmarschall by Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler was an Austrian-born German politician and the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party , commonly referred to as the Nazi Party). He was Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and head of state from 1934 to 1945...

. Hitler expected Paulus to commit suicide, citing the fact that there was no record of a German field marshal ever surrendering to enemy forces. While in Soviet captivity during the war Paulus became a vocal critic of the Nazi regime and joined the Russian-sponsored National Committee for a Free Germany

National Committee for a Free Germany

The National Committee for a Free Germany was a German anti-Nazi organization that operated in the Soviet Union during World War II.- History :...

. He was not released until 1953.

Early life

Paulus was born in BreitenauGuxhagen

Guxhagen is a community in Schwalm-Eder district in northern Hesse, Germany.-Geography:Guxhagen lies about 15 km south of Kassel between the Habichtswald Nature Park and the Meißner-Kaufunger Wald Nature Park on the river Fulda. It neighbors Edermünde, Felsberg, Fuldabrück and Körle...

, Hesse-Nassau, the son of a school teacher.

He tried, unsuccessfully, to secure a cadetship in the Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine

The Imperial German Navy was the German Navy created at the time of the formation of the German Empire. It existed between 1871 and 1919, growing out of the small Prussian Navy and Norddeutsche Bundesmarine, which primarily had the mission of coastal defense. Kaiser Wilhelm II greatly expanded...

and briefly studied law at Marburg University.

Military career

After leaving the university without a degree, he joined the 111th Infantry Regiment as an officer cadet in February 1910. He married Elena Rosetti-Solescu on 4 July, 1912.When World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

began, Paulus's regiment was part of the thrust into France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

, and he saw action in the Vosges

Vosges

Vosges is a French department, named after the local mountain range. It contains the hometown of Joan of Arc, Domrémy.-History:The Vosges department is one of the original 83 departments of France, created on February 9, 1790 during the French Revolution. It was made of territories that had been...

and around Arras

Arras

Arras is the capital of the Pas-de-Calais department in northern France. The historic centre of the Artois region, its local speech is characterized as a Picard dialect...

in the autumn of 1914. After a leave of absence due to illness, he joined the Alpenkorps

Alpenkorps (German Empire)

The Alpenkorps was a provisional mountain unit of division size formed by the Imperial German Army during World War I. It was considered by the Allies to be one of the best units of the German Army.-Formation:...

as a staff officer, serving in Macedonia

Macedonia (region)

Macedonia is a geographical and historical region of the Balkan peninsula in southeastern Europe. Its boundaries have changed considerably over time, but nowadays the region is considered to include parts of five Balkan countries: Greece, the Republic of Macedonia, Bulgaria, Albania, Serbia, as...

, France and Serbia

Serbia

Serbia , officially the Republic of Serbia , is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central and Southeast Europe, covering the southern part of the Carpathian basin and the central part of the Balkans...

. By the end of the war, he was a captain.

After the Armistice, Paulus fought with the Freikorps

Freikorps

Freikorps are German volunteer military or paramilitary units. The term was originally applied to voluntary armies formed in German lands from the middle of the 18th century onwards. Between World War I and World War II the term was also used for the paramilitary organizations that arose during...

in the east as a brigade adjutant. He remained in the scaled-down Reichswehr

Reichswehr

The Reichswehr formed the military organisation of Germany from 1919 until 1935, when it was renamed the Wehrmacht ....

that came into being after the Treaty of Versailles

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was one of the peace treaties at the end of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1919, exactly five years after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The other Central Powers on the German side of...

and was assigned to the 13th Infantry Regiment at Stuttgart

Stuttgart

Stuttgart is the capital of the state of Baden-Württemberg in southern Germany. The sixth-largest city in Germany, Stuttgart has a population of 600,038 while the metropolitan area has a population of 5.3 million ....

as a company commander. He served in various staff positions for over a decade (1921–1933) and then briefly commanded a motorized battalion (1934–1935) before being named chief of staff for the Panzer

Panzer

A Panzer is a German language word that, when used as a noun, means "tank". When it is used as an adjective, it means either tank or "armoured" .- Etymology :...

headquarters in October 1935, a new formation under Lutz

Oswald Lutz

General Oswald Lutz was a German General who oversaw the motorization of the German Army in the late 1920s and early 1930s and was appointed as the first General der Panzertruppe of the Wehrmacht in 1935....

that directed the training and development of the army's three panzer divisions.

In February 1938 Paulus was appointed Chef des Generalstabes to Guderian

Heinz Guderian

Heinz Wilhelm Guderian was a German general during World War II. He was a pioneer in the development of armored warfare, and was the leading proponent of tanks and mechanization in the Wehrmacht . Germany's panzer forces were raised and organized under his direction as Chief of Mobile Forces...

's new XVI Armeekorps (Motorisiert), which replaced Lutz's command. Guderian described him as ‘brilliantly clever, conscientious, hard working, original and talented’ but already had doubts about his decisiveness, toughness and lack of command experience. He remained in that post until May 1939, when he was promoted to Major General

Major General

Major general or major-general is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. A major general is a high-ranking officer, normally subordinate to the rank of lieutenant general and senior to the ranks of brigadier and brigadier general...

and became Chief of Staff for the German Tenth Army

German Tenth Army

The 10th Army was a World War I and World War II field army. During World War I the 10th army was stationed at the Eastern Front against Russia, and occupied Poland and Belorussia at the end of 1918 when the war ended....

, with which he saw service in Poland

Poland

Poland , officially the Republic of Poland , is a country in Central Europe bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania to the east; and the Baltic Sea and Kaliningrad Oblast, a Russian exclave, to the north...

, the Netherlands

Netherlands

The Netherlands is a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, located mainly in North-West Europe and with several islands in the Caribbean. Mainland Netherlands borders the North Sea to the north and west, Belgium to the south, and Germany to the east, and shares maritime borders...

and Belgium

Belgium

Belgium , officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a federal state in Western Europe. It is a founding member of the European Union and hosts the EU's headquarters, and those of several other major international organisations such as NATO.Belgium is also a member of, or affiliated to, many...

(by the latter two campaigns, the army had been renumbered as the Sixth Army

German Sixth Army

The 6th Army was a designation for German field armies which saw action in World War I and World War II. The 6th Army is best known for fighting in the Battle of Stalingrad, during which it became the first entire German field army to be completely destroyed...

).

Paulus was promoted to Lieutenant General

Lieutenant General

Lieutenant General is a military rank used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages where the title of Lieutenant General was held by the second in command on the battlefield, who was normally subordinate to a Captain General....

in August 1940 and the following month he was named deputy chief of the German General Staff

German General Staff

The German General Staff was an institution whose rise and development gave the German armed forces a decided advantage over its adversaries. The Staff amounted to its best "weapon" for nearly a century and a half....

(OQu I). In that role he helped draft the plans for the invasion of the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

.

Stalingrad

General der Panzertruppe

General der Panzertruppe was a rank of German Army General introduced by the Wehrmacht in 1935. As the commander of a Panzer Corp this rank corresponds to a US Army Lieutenant-General...

and became commander of the German Sixth Army in January 1942 and led the drive on Stalingrad during that summer. Paulus' troops fought the defending Soviet troops holding Stalingrad over three months in increasingly brutal urban warfare. In November 1942, when the Soviet Red Army

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army started out as the Soviet Union's revolutionary communist combat groups during the Russian Civil War of 1918-1922. It grew into the national army of the Soviet Union. By the 1930s the Red Army was among the largest armies in history.The "Red Army" name refers to...

launched a massive counter-offensive, code named Operation Uranus

Operation Uranus

Operation Uranus was the codename of the Soviet strategic operation in World War II which led to the encirclement of the German Sixth Army, the Third and Fourth Romanian armies, and portions of the German Fourth Panzer Army. The operation formed part of the ongoing Battle of Stalingrad, and was...

, Paulus found himself surrounded by an entire Soviet Army Group.

Paulus followed Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler was an Austrian-born German politician and the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party , commonly referred to as the Nazi Party). He was Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and head of state from 1934 to 1945...

's orders to hold the Army's position in Stalingrad under all circumstances, despite the fact that he was completely surrounded by strong Russian formations. A relief effort by Army Group Don

Army Group Don

Army Group Don was a short-lived German army group during World War II.Army Group Don was created from the headquarters of the Eleventh Army in the southern sector of the Eastern Front on 22 November 1942. The army group only lasted until February 1943 when it was combined with Army Group B and...

under Field Marshal Erich von Manstein

Erich von Manstein

Erich von Manstein was a field marshal in World War II. He became one of the most prominent commanders of Germany's World War II armed forces...

failed in December, inevitably: insufficient force was available to challenge the Soviet forces encircling the German 6th Army, and Hitler refused to allow Paulus to break out of Stalingrad despite Manstein telling him it was the only way the effort would succeed. By this time, Paulus' remaining armour had only sufficient fuel for a 12-mile advance anyway. In any event, Paulus was refused permission to break out of the encirclement. Kurt Zeitzler

Kurt Zeitzler

Kurt Zeitzler was an officer in the German Reichswehr and its successor the Wehrmacht, most prominent for being the Chief of the Army General Staff from 1942 to 1944.- World War I and after :...

, the newly appointed chief of the Army General Staff

German General Staff

The German General Staff was an institution whose rise and development gave the German armed forces a decided advantage over its adversaries. The Staff amounted to its best "weapon" for nearly a century and a half....

, eventually got Hitler to allow Paulus to break out—provided they held onto Stalingrad, an impossible task.

For the next two months, Paulus and his men fought on. However, the lack of ammunition, equipment attrition and deteriorating physical condition of the German troops prevented them from defending effectively against the Red Army. The battle was fought with terrible losses on both sides and great suffering.

Konstantin Rokossovsky

Konstantin Rokossovskiy was a Polish-origin Soviet career officer who was a Marshal of the Soviet Union, as well as Marshal of Poland and Polish Defence Minister, who was famously known for his service in the Eastern Front, where he received high esteem for his outstanding military skill...

, commander of the Red Army on the Don front, called a cease fire and offered Paulus' men generous surrender terms—normal rations, medical treatment for the ill and wounded, permission to retain their badges, decorations, uniforms and personal effects, and repatriation to any country they wished after the war. Rokossovsky also noted that Paulus was in a nearly impossible situation. By this time, there was no hope for Paulus to be relieved or supplied by air, and most of his men had no winter clothing. However, when Paulus asked Hitler for permission to surrender, Hitler rejected this request almost out of hand and ordered him to hold Stalingrad to the last man.

After a heavy Soviet offensive overran the last emergency airstrip in Stalingrad on 25 January, the Russians again offered Paulus a chance to surrender. Once again, Hitler ordered Paulus to hold Stalingrad to the death. On 30 January, Paulus informed Hitler that his men were hours from collapse. Hitler responded by showering a raft of field promotions by radio on Paulus' officers to build up their spirits and steel their will to hold their ground. Most significantly, he promoted Paulus to field marshal. In deciding to promote Paulus, Hitler noted that there was no known record of a Prussia

Prussia

Prussia was a German kingdom and historic state originating out of the Duchy of Prussia and the Margraviate of Brandenburg. For centuries, the House of Hohenzollern ruled Prussia, successfully expanding its size by way of an unusually well-organized and effective army. Prussia shaped the history...

n or German field marshal ever having surrendered. The implication was clear: Paulus was to commit suicide. If Paulus surrendered, he would shame Germany's military history.

Despite this, and to the disgust of Hitler, Paulus and his staff surrendered the next day, 31 January. On the 2 February 1943 the remainder of the Sixth Army capitulated. Upon finding out about Paulus' surrender, Hitler flew into a rage, and vowed never to appoint another field marshal again, though he would in fact go on to appoint another seven field marshals in his lifetime. Speaking about the surrender of Paulus, Hitler told his staff:

Paulus, a Roman Catholic, was opposed to suicide. During his captivity, according to General Pfeffer

Franz Pfeffer von Salomon

Franz Pfeffer von Salomon was the first commander of the SA after its 1925 restoration, which followed its temporary abolition in 1923 after the abortive Beer Hall Putsch....

, Paulus said of Hitler's expectation: "I have no intention of shooting myself for this Bohemia

Bohemia

Bohemia is a historical region in central Europe, occupying the western two-thirds of the traditional Czech Lands. It is located in the contemporary Czech Republic with its capital in Prague...

n private

Gefreiter

Gefreiter is the German, Swiss and Austrian equivalent for the military rank Private . Gefreiter was the lowest rank to which an ordinary soldier could be promoted. As a military rank it has existed since at least the 16th century...

". Another general told the NKVD

NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs was the public and secret police organization of the Soviet Union that directly executed the rule of power of the Soviets, including political repression, during the era of Joseph Stalin....

that Paulus had told him about his promotion to field marshal and said: "It looks like an invitation to commit suicide, but I will not do this favour for him." Paulus also forbade his soldiers from standing on top of their trenches in order to be shot by the enemy.

After Stalingrad and postwar

Although he at first refused to collaborate with the Soviets, after the attempted assassinationJuly 20 Plot

On 20 July 1944, an attempt was made to assassinate Adolf Hitler, Führer of the Third Reich, inside his Wolf's Lair field headquarters near Rastenburg, East Prussia. The plot was the culmination of the efforts of several groups in the German Resistance to overthrow the Nazi-led German government...

of Hitler on 20 July 1944, Paulus became a vocal critic of the Nazi regime while in Soviet captivity, joining the Russian-sponsored National Committee for a Free Germany

National Committee for a Free Germany

The National Committee for a Free Germany was a German anti-Nazi organization that operated in the Soviet Union during World War II.- History :...

and appealing to Germans to surrender. He later acted as a witness for the prosecution at the Nuremberg Trials

Nuremberg Trials

The Nuremberg Trials were a series of military tribunals, held by the victorious Allied forces of World War II, most notable for the prosecution of prominent members of the political, military, and economic leadership of the defeated Nazi Germany....

. He was released in 1953, two years before the repatriation of the remaining German POWs (mostly other Stalingrad veterans) who had been designated war criminals by the Soviets

Forced labor of Germans in the Soviet Union

Forced labor of Germans in the Soviet Union was considered by the Soviet Union to be part of German war reparations for the damage inflicted by Nazi Germany on the Soviet Union during World War II. German civilians in Eastern Europe were deported to the USSR after World War II as forced laborers...

. Paulus settled in the German Democratic Republic

German Democratic Republic

The German Democratic Republic , informally called East Germany by West Germany and other countries, was a socialist state established in 1949 in the Soviet zone of occupied Germany, including East Berlin of the Allied-occupied capital city...

(East Germany).

During the Nuremberg Trials, Paulus was asked about the Stalingrad prisoners by a journalist. Paulus told the journalist to tell the wives and mothers that their husbands and sons were well. Of the 91,000 German prisoners taken at Stalingrad, half had died on the march to Siberia

Siberia

Siberia is an extensive region constituting almost all of Northern Asia. Comprising the central and eastern portion of the Russian Federation, it was part of the Soviet Union from its beginning, as its predecessor states, the Tsardom of Russia and the Russian Empire, conquered it during the 16th...

n prison camps, nearly as many died in captivity; only about 6,000 returned home.

From 1953 to 1956, he lived in Dresden

Dresden

Dresden is the capital city of the Free State of Saxony in Germany. It is situated in a valley on the River Elbe, near the Czech border. The Dresden conurbation is part of the Saxon Triangle metropolitan area....

, East Germany, where he worked as the civilian chief of the East German Military History Research Institute and not, as often wrongly described, as an inspector of police. In late 1956, he developed motor neuron disease

Motor neurone disease

The motor neurone diseases are a group of neurological disorders that selectively affect motor neurones, the cells that control voluntary muscle activity including speaking, walking, breathing, swallowing and general movement of the body. They are generally progressive in nature, and can cause...

and was eventually left paralyzed. He died in Dresden on 1 February 1957, exactly 14 years after he surrendered at Stalingrad. His body was brought for burial in Baden

Baden

Baden is a historical state on the east bank of the Rhine in the southwest of Germany, now the western part of the Baden-Württemberg of Germany....

next to that of his wife, who had died in 1949 having not seen her husband since his surrender.