German occupation of Luxembourg in World War I

Encyclopedia

Military occupation

Military occupation occurs when the control and authority over a territory passes to a hostile army. The territory then becomes occupied territory.-Military occupation and the laws of war:...

s of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Luxembourg , officially the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg , is a landlocked country in western Europe, bordered by Belgium, France, and Germany. It has two principal regions: the Oesling in the North as part of the Ardennes massif, and the Gutland in the south...

by Germany

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

in the twentieth century. From August 1914 until the end of World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

in November 1918, Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Luxembourg , officially the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg , is a landlocked country in western Europe, bordered by Belgium, France, and Germany. It has two principal regions: the Oesling in the North as part of the Ardennes massif, and the Gutland in the south...

was under full occupation by the German Empire

German Empire

The German Empire refers to Germany during the "Second Reich" period from the unification of Germany and proclamation of Wilhelm I as German Emperor on 18 January 1871, to 1918, when it became a federal republic after defeat in World War I and the abdication of the Emperor, Wilhelm II.The German...

. The German government justified the occupation by citing the need to support their armies

Army

An army An army An army (from Latin arma "arms, weapons" via Old French armée, "armed" (feminine), in the broadest sense, is the land-based military of a nation or state. It may also include other branches of the military such as the air force via means of aviation corps...

in neighbouring France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

, although many Luxembourgers, contemporary and present, have interpreted German actions otherwise.

During this period, Luxembourg was allowed to retain its own government and political system, but all proceedings were overshadowed by the German army's presence. Despite the overbearing distraction of the occupation, the Luxembourgian people attempted to lead their lives as normally as possible. The political parties attempted to focus on other matters, such as the economy

Economy

An economy consists of the economic system of a country or other area; the labor, capital and land resources; and the manufacturing, trade, distribution, and consumption of goods and services of that area...

, education

Education

Education in its broadest, general sense is the means through which the aims and habits of a group of people lives on from one generation to the next. Generally, it occurs through any experience that has a formative effect on the way one thinks, feels, or acts...

, and constitutional reform.

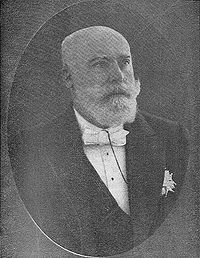

The domestic political environment was further complicated by the death of Paul Eyschen

Paul Eyschen

Paul Eyschen was a Luxembourgish politician, statesman, lawyer, and diplomat. He was the eighth Prime Minister of Luxembourg, serving for twenty-seven years, from 22 September 1888 until his death, on 11 October 1915....

, who had been Prime Minister for 27 years. With his death came a string of short-lived governments, culminating in rebellion, and constitutional turmoil after the withdrawal of German soldiers.

Background

Since the 1867 Treaty of London, Luxembourg had been an explicitly neutral stateNeutral country

A neutral power in a particular war is a sovereign state which declares itself to be neutral towards the belligerents. A non-belligerent state does not need to be neutral. The rights and duties of a neutral power are defined in Sections 5 and 13 of the Hague Convention of 1907...

. The Luxembourg Crisis

Luxembourg Crisis

The Luxembourg Crisis was a diplomatic dispute and confrontation in 1867 between France and Prussia over the political status of Luxembourg. The confrontation almost led to war between the two parties, but was peacefully resolved by the Treaty of London....

had seen Prussia

Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia was a German kingdom from 1701 to 1918. Until the defeat of Germany in World War I, it comprised almost two-thirds of the area of the German Empire...

thwart France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

's attempt to purchase the Grand Duchy from the Netherlands

Netherlands

The Netherlands is a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, located mainly in North-West Europe and with several islands in the Caribbean. Mainland Netherlands borders the North Sea to the north and west, Belgium to the south, and Germany to the east, and shares maritime borders...

. Luxembourg's neutrality was accepted by Prussia's then-Chancellor, Otto von Bismarck

Otto von Bismarck

Otto Eduard Leopold, Prince of Bismarck, Duke of Lauenburg , simply known as Otto von Bismarck, was a Prussian-German statesman whose actions unified Germany, made it a major player in world affairs, and created a balance of power that kept Europe at peace after 1871.As Minister President of...

, who boasted, "In exchange for the fortress of Luxembourg, we have been compensated by the neutrality of the country, and a guarantee that it shall be maintained in perpetuity."

In June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand

Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria

Franz Ferdinand was an Archduke of Austria-Este, Austro-Hungarian and Royal Prince of Hungary and of Bohemia, and from 1889 until his death, heir presumptive to the Austro-Hungarian throne. His assassination in Sarajevo precipitated Austria-Hungary's declaration of war against Serbia...

, heir to the thrones of Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary , more formally known as the Kingdoms and Lands Represented in the Imperial Council and the Lands of the Holy Hungarian Crown of Saint Stephen, was a constitutional monarchic union between the crowns of the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary in...

, was assassinated by pan-Slavic nationalists, leading to a sudden deterioration in relations between Austria-Hungary and Serbia

Serbia

Serbia , officially the Republic of Serbia , is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central and Southeast Europe, covering the southern part of the Carpathian basin and the central part of the Balkans...

. Austria-Hungary was supported by the German Empire

German Empire

The German Empire refers to Germany during the "Second Reich" period from the unification of Germany and proclamation of Wilhelm I as German Emperor on 18 January 1871, to 1918, when it became a federal republic after defeat in World War I and the abdication of the Emperor, Wilhelm II.The German...

, whilst Serbia had the backing of the Russian Empire

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

. On 28 July, Austria-Hungary attacked Serbia, which, in turn, required the mobilisation

Mobilization

Mobilization is the act of assembling and making both troops and supplies ready for war. The word mobilization was first used, in a military context, in order to describe the preparation of the Prussian army during the 1850s and 1860s. Mobilization theories and techniques have continuously changed...

of Russia, hence of Germany, thanks to its responsibilities under the Dual Alliance

Dual Alliance, 1879

The Dual Alliance was a defensive alliance between Germany and Austria-Hungary, which was created by treaty on October 7, 1879 as part of Bismarck's system of alliances to prevent/limit war. In it, Germany and Austria-Hungary pledged to aid one another in case of an attack by Russia...

.

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

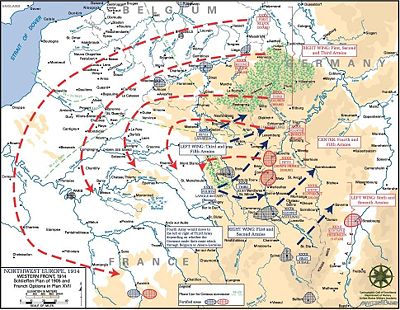

, Germany put into action the Schlieffen Plan

Schlieffen Plan

The Schlieffen Plan was the German General Staff's early 20th century overall strategic plan for victory in a possible future war in which the German Empire might find itself fighting on two fronts: France to the west and Russia to the east...

. Under this military strategy, formulated by Count Schlieffen in 1905, Germany would launch a lightning attack on France through the poorly-defended Low Countries

Low Countries

The Low Countries are the historical lands around the low-lying delta of the Rhine, Scheldt, and Meuse rivers, including the modern countries of Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg and parts of northern France and western Germany....

. This would bypass France’s main defences, arranged to the south. Germany’s army would be able to encircle Paris

Paris

Paris is the capital and largest city in France, situated on the river Seine, in northern France, at the heart of the Île-de-France region...

, force France to surrender, and turn its full attention to the Eastern Front

Eastern Front (World War I)

The Eastern Front was a theatre of war during World War I in Central and, primarily, Eastern Europe. The term is in contrast to the Western Front. Despite the geographical separation, the events in the two theatres strongly influenced each other...

.

Since the 1860s, Luxembourgers had been keenly aware of German ambition, and Luxembourg's government was well aware of the implications of the Schlieffen Plan. In 1911, Prime Minister Paul Eyschen

Paul Eyschen

Paul Eyschen was a Luxembourgish politician, statesman, lawyer, and diplomat. He was the eighth Prime Minister of Luxembourg, serving for twenty-seven years, from 22 September 1888 until his death, on 11 October 1915....

commissioned an engineer to evaluate Germany's western railroad network, particularly the likelihood that Germany would occupy Luxembourg to suit its logistical needs for a campaign in France. Moreover, given the strong ethnic and linguistic links between Luxembourg and Germany, it was feared that Germany might seek to annex

Annexation

Annexation is the de jure incorporation of some territory into another geo-political entity . Usually, it is implied that the territory and population being annexed is the smaller, more peripheral, and weaker of the two merging entities, barring physical size...

Luxembourg into its empire. The government of Luxembourg aimed to avoid this by re-affirming the country's neutrality.

Invasion

Albrecht, Duke of Württemberg

Albrecht, Duke of Württemberg or Albrecht Herzog von Württemberg was a German Generalfeldmarschall and head of the Royal House of Württemberg...

Fourth Army

German Fourth Army

The 4th Army was a field army of Imperial Germany during World War I and of the Wehrmacht during World War II-World War I:At the outset of war, the Fourth Army, with the Fifth Army, formed the center of the German armies on the Western Front, moving through Luxembourg and Belgium in support of the...

. One of the railways from the northern Rhineland

Rhineland

Historically, the Rhinelands refers to a loosely-defined region embracing the land on either bank of the River Rhine in central Europe....

into France passed through Troisvierges

Troisvierges

Troisvierges is a commune and town in northern Luxembourg, in the canton of Clervaux. The two highest hills in Luxembourg, the Kneiff and Buurgplaatz , are located in the commune....

, in the far north of Luxembourg, and Germany's first infringement of Luxembourg's sovereignty and neutrality was the unauthorised use of Troisvierges station

Troisvierges railway station

Troisvierges railway station is a railway station serving Troisvierges, in northern Luxembourg. It is operated by Chemins de Fer Luxembourgeois, the state-owned railway company....

. Eyschen protested, but could do nothing to prevent Germany's incursion.

The next day, Germany launched a full invasion. German soldiers began moving through south-eastern Luxembourg, crossing the Moselle River

Moselle River

The Moselle is a river flowing through France, Luxembourg, and Germany. It is a left tributary of the Rhine, joining the Rhine at Koblenz. A small part of Belgium is also drained by the Mosel through the Our....

at Remich

Remich

Remich is a commune with city status in south-eastern Luxembourg with just under 3,000 inhabitants. It is the capital of the canton of Remich, which is part of the district of Grevenmacher. Remich lies on the left bank of the Moselle river, which forms part of the border between Luxembourg and...

and Wasserbillig

Wasserbillig

Wasserbillig is a town in the commune of Mertert, in eastern Luxembourg. , Wasserbillig has 2,186 inhabitants, which makes it the largest town in Mertert. It lies at the confluence of the rivers Moselle and Sauer, which form the border with Germany at the town...

, and headed towards the capital, Luxembourg City. Tens of thousands of German soldiers had been deployed to Luxembourg in those twenty-four hours (although the Grand Duchy's government refuted any precise number that was suggested). Grand Duchess

Grand Duke of Luxembourg

The Grand Duke of Luxembourg is the sovereign monarch and head of state of Luxembourg. Luxembourg has been a grand duchy since 15 March 1815, when it was elevated from a duchy when placed in personal union with the United Kingdom of the Netherlands...

Marie-Adélaïde ordered that the Grand Duchy's small army, which numbered under 400, not resist, and, on the afternoon of the 2 August, she and Eyschen met the German commander, Oberst

Oberst

Oberst is a military rank in several German-speaking and Scandinavian countries, equivalent to Colonel. It is currently used by both the ground and air forces of Austria, Germany, Switzerland, Denmark and Norway. The Swedish rank överste is a direct translation, as are the Finnish rank eversti...

Richard Karl von Tessmar

Richard Karl von Tessmar

Generalmajor Richard Karl von Tessmar was a German soldier.He is notable primarily for his exploits during the First World War, during which he was commanded the German forces occupying Luxembourg. He led the forces that captured Luxembourg City on the 2 August 1914, before establishing his...

, on Luxembourg City's Adolphe Bridge

Adolphe Bridge

Adolphe Bridge is an arch bridge in Luxembourg City, in southern Luxembourg. The bridge takes road traffic across the Pétrusse, connecting Boulevard Royal, in Ville Haute, to Avenue de la Liberté, in Gare...

, the symbol of Luxembourg's modernisation. They protested mildly, but both the young Grand Duchess and her aging statesman accepted German military rule as inevitable.

Reichstag (German Empire)

The Reichstag was the parliament of the North German Confederation , and of the German Reich ....

:

However, when it seemed that Germany was on the verge of victory, the Chancellor began to revise his statements. In his Septemberprogramm

Septemberprogramm

The Septemberprogramm was a plan drafted by the German leadership in the early weeks of the First World War. It detailed Germany's ambitious gains should it win the war, as it expected...

, Bethmann Hollweg called for Luxembourg to become a German federal state, and for that result to be forced upon the Luxembourgian people once Germany achieved victory over the Triple Entente

Triple Entente

The Triple Entente was the name given to the alliance among Britain, France and Russia after the signing of the Anglo-Russian Entente in 1907....

. Given this promise, it came as a great relief to most Luxembourgers that the British

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the formal name of the United Kingdom during the period when what is now the Republic of Ireland formed a part of it....

and French halted the German advance at the Battle of the Marne

First Battle of the Marne

The Battle of the Marne was a First World War battle fought between 5 and 12 September 1914. It resulted in an Allied victory against the German Army under Chief of Staff Helmuth von Moltke the Younger. The battle effectively ended the month long German offensive that opened the war and had...

in mid-September. The result for the combatant nations was trench warfare

Trench warfare

Trench warfare is a form of occupied fighting lines, consisting largely of trenches, in which troops are largely immune to the enemy's small arms fire and are substantially sheltered from artillery...

, but, for Luxembourg, it was the indefinite continuation of German occupation.

Eyschen government

Western Front (World War I)

Following the outbreak of World War I in 1914, the German Army opened the Western Front by first invading Luxembourg and Belgium, then gaining military control of important industrial regions in France. The tide of the advance was dramatically turned with the Battle of the Marne...

, so the fate of Luxembourg was see-sawing back and forth. It was clear to all that the good conduct of the Luxembourgian government, if fully receptive to the needs of the German military administrators, could guarantee Luxembourg's continued self-government, at least in the short-term. Eyschen

Paul Eyschen

Paul Eyschen was a Luxembourgish politician, statesman, lawyer, and diplomat. He was the eighth Prime Minister of Luxembourg, serving for twenty-seven years, from 22 September 1888 until his death, on 11 October 1915....

was a familiar and overwhelmingly popular leader, and all factions put their utmost faith in his ability to steer Luxembourg through the diplomatic minefield that was occupation. On 4 August 1914, he expelled the French minister in Luxembourg at the request of the German minister, followed by the Belgian minister four days later and the Italian minister when his country entered the war. To the same end, Eyschen refused to speak ill of the German Zollverein

Zollverein

thumb|upright=1.2|The German Zollverein 1834–1919blue = Prussia in 1834 grey= Included region until 1866yellow= Excluded after 1866red = Borders of the German Union of 1828 pink= Relevant others until 1834...

, even though he had talked openly of exiting the customs union

Customs union

A customs union is a type of trade bloc which is composed of a free trade area with a common external tariff. The participant countries set up common external trade policy, but in some cases they use different import quotas...

before the war began.

On occasions, Eyschen's principles got the better of him. On 13 October 1914, a Luxembourgian journalist named Karl Dardar was arrested by the German army for publishing anti-German stories. He was then taken to Koblenz

Koblenz

Koblenz is a German city situated on both banks of the Rhine at its confluence with the Moselle, where the Deutsches Eck and its monument are situated.As Koblenz was one of the military posts established by Drusus about 8 BC, the...

, and tried and sentenced by court-martial

Court-martial

A court-martial is a military court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of members of the armed forces subject to military law, and, if the defendant is found guilty, to decide upon punishment.Most militaries maintain a court-martial system to try cases in which a breach of...

to three months imprisonment

Imprisonment

Imprisonment is a legal term.The book Termes de la Ley contains the following definition:This passage was approved by Atkin and Duke LJJ in Meering v Grahame White Aviation Co....

. Eyschen was outraged that the Germans had kidnapped a Luxembourgian citizen and tried him for an extraterritorial offence, and Eyschen did nothing to hide his indignation. Eyschen told the German minister in Luxembourg that the action was a 'direct injury to the Grand Duchy's national sovereignty'.

Such vexatious complaints were repeated, by both Eyschen and Victor Thorn, when a railway worker was arrested in January 1915 for allegedly working for French military intelligence

Military intelligence

Military intelligence is a military discipline that exploits a number of information collection and analysis approaches to provide guidance and direction to commanders in support of their decisions....

, and subsequently tried and sentenced in Trier

Trier

Trier, historically called in English Treves is a city in Germany on the banks of the Moselle. It is the oldest city in Germany, founded in or before 16 BC....

. As Minister for Justice

Minister for Justice

The Scottish Cabinet Secretary for Justice, commonly referred to as the Justice Secretary, is a cabinet position in the Scottish Government...

, Thorn was incensed that the Luxembourgian legal system had been treated with such disdain. Such objections were not received well by the German authorities. Although they tired of Eyschen's stubborn ways, he remained a useful tool to unite the various Luxembourgian political factions.

Eyschen was not alone in letting his principles obstruct government business. In the summer of 1915, Eyschen pushed to further reduce the role of the Catholic Church in the state school system. Grand Duchess Marie-Adélaïde objected. A fervently religious Catholic (as was most of the country, but not her late father, who was Protestant

Protestantism

Protestantism is one of the three major groupings within Christianity. It is a movement that began in Germany in the early 16th century as a reaction against medieval Roman Catholic doctrines and practices, especially in regards to salvation, justification, and ecclesiology.The doctrines of the...

), she was reputed to have said, "I will not allow their most precious heritage [Roman Catholicism] to be stolen while I have the key." Marie-Adélaïde refused to budge, inviting Eyschen to resign if he could not accept her decision. Eyschen nearly did, but decided to control himself. Nevertheless, he would not be long in the job.

Eyschen's death

Critically, Eyschen had the confidence of the Chamber of Deputies

Chamber of Deputies of Luxembourg

The Chamber of Deputies , abbreviated to the Chamber, is the unicameral national legislature of Luxembourg. 'Krautmaart' is sometimes used as a metonym for the Chamber, after the square on which the Hôtel de la Chambre is located....

, and he had managed to hold together a government containing all major factions, seemingly by force of personality alone. To make matters worse for national unity, the strain of occupation had broken apart the pre-war anti-clericalist

Anti-clericalism

Anti-clericalism is a historical movement that opposes religious institutional power and influence, real or alleged, in all aspects of public and political life, and the involvement of religion in the everyday life of the citizen...

alliance between the socialist

Socialism

Socialism is an economic system characterized by social ownership of the means of production and cooperative management of the economy; or a political philosophy advocating such a system. "Social ownership" may refer to any one of, or a combination of, the following: cooperative enterprises,...

and the liberal

Liberalism

Liberalism is the belief in the importance of liberty and equal rights. Liberals espouse a wide array of views depending on their understanding of these principles, but generally, liberals support ideas such as constitutionalism, liberal democracy, free and fair elections, human rights,...

factions, thus depriving both the clericalists and anti-clericalists of a legislative majority

Majority

A majority is a subset of a group consisting of more than half of its members. This can be compared to a plurality, which is a subset larger than any other subset; i.e. a plurality is not necessarily a majority as the largest subset may consist of less than half the group's population...

. The Catholic

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the world's largest Christian church, with over a billion members. Led by the Pope, it defines its mission as spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ, administering the sacraments and exercising charity...

conservatives

Conservatism

Conservatism is a political and social philosophy that promotes the maintenance of traditional institutions and supports, at the most, minimal and gradual change in society. Some conservatives seek to preserve things as they are, emphasizing stability and continuity, while others oppose modernism...

formed the largest bloc, but they were least likely to form a majority coalition

Coalition

A coalition is a pact or treaty among individuals or groups, during which they cooperate in joint action, each in their own self-interest, joining forces together for a common cause. This alliance may be temporary or a matter of convenience. A coalition thus differs from a more formal covenant...

.

Mongenast government

The day after Eyschen's death, Grand Duchess Marie-Adélaïde invited Mathias Mongenast, who had been Minister for Finance since 1882, to form a minority government. Mongenast's special status as a 'caretaker' Prime Minister is underlined by his official title; he was not 'President of the GovernmentPresident of the Government

President of the Government is a term used in official statements to describe several Prime Ministers:* Croatia, Prime Minister of Croatia* Russia, Prime Minister of Russia, Literally Chairman of the Government...

', as all other Prime Ministers since 1857 had been, but held the lesser title of 'President of the Council

President of the Council

President of the Council can refer to:*President of the Council of Ministers*Lord President of the Council...

'.

Mongenast's administration was never intended to be long-lived, and Marie-Adélaïde's main objective when appointing the experienced Mongenast was to steady the ship. Nevertheless, nobody expected the government to fall as soon as it did. On 4 November 1915, Mongenast nominated a new candidate for head of Luxembourg's école normale

Normal school

A normal school is a school created to train high school graduates to be teachers. Its purpose is to establish teaching standards or norms, hence its name...

. The nomination did not meet with Grand Ducal approval, and Marie-Adélaïde rejected him. Mongenast persisted; education had been a hobby horse of his, and he imagined that the Grand Duchess would accept the advice of a minister as experienced as he was. He was wrong; the Grand Duchess had always been single-minded, and resented a minority Prime Minister, particularly one so new to the job, making demands of her. The next day, Mongenast resigned, just twenty-five days after being given the job.

Loutsch government

Having fought with Mongenast, the Grand Duchess decided to appoint an all-conservative cabinet. The Chamber of Deputies was steadfastly opposed; the Party of the RightParty of the Right (Luxembourg)

The Party of the Right , abbreviated to PD, was a political party in Luxembourg between 1914 and 1944. It was the direct predecessor of the Christian Social People's Party , which has ruled Luxembourg for all but five years since....

held only 20 seats out of 52, but they formed the plurality. Marie-Adélaïde sought to end this deadlock by dissolving

Dissolution of parliament

In parliamentary systems, a dissolution of parliament is the dispersal of a legislature at the call of an election.Usually there is a maximum length of a legislature, and a dissolution must happen before the maximum time...

the Chamber of Deputies and by calling for the voters to grant a mandate to the conservatives. This outraged the left, which assumed that its deputies alone had the constitutional right to grant the government confidence; it was dubbed by those on the left a 'coup d'état

Coup d'état

A coup d'état state, literally: strike/blow of state)—also known as a coup, putsch, and overthrow—is the sudden, extrajudicial deposition of a government, usually by a small group of the existing state establishment—typically the military—to replace the deposed government with another body; either...

by the Grand Duchess'. Nonetheless, on 23 December 1915, Luxembourg went to the polls. Although the position of the Party of the Right was improved, taking 25 seats, it fell a whisker short of winning an absolute majority. On 11 January 1916, the Chamber of Deputies passed a motion of no confidence

Motion of no confidence

A motion of no confidence is a parliamentary motion whose passing would demonstrate to the head of state that the elected parliament no longer has confidence in the appointed government.-Overview:Typically, when a parliament passes a vote of no...

, and Loutsch resigned.

Forming a consensus

After the failure of the all-conservative government, the Grand Duchess turned to the leading liberal politician, Victor Thorn, to form a new government. After Eyschen's premiership of 27 years, two governments had come and gone in three months, and the Luxembourgian people were becoming disillusioned with the failure of the politicians. Thorn's nature was to be a conciliatory leader, and he made a direct appeal to the Chamber of Deputies to support his government, no matter the deputies' individual ideological persuasions: "If you want a government that acts, and is capable of acting, it is imperative that all parties support this government." This support was forthcoming from all parties, but only on the condition that each was invited into the government; Thorn was left with no choice but to afford them this. The resulting grand coalitionGrand coalition

A grand coalition is an arrangement in a multi-party parliamentary system in which the two largest political parties of opposing political ideologies unite in a coalition government...

cabinet included every leading light in Luxembourgian politics; besides Thorn himself, there were the conservatives Léon Kauffmann and Antoine Lefort

Antoine Lefort

Antoine Lefort-Mousel was a Luxembourgian politician and diplomat. A member of Luxembourg's Chamber of Deputies for the Party of the Right, he served as the Director-General for Public Works from 24 February 1916 until 28 September 1918. Later, he served as a diplomat, including as chargé...

, the socialist leader Dr Michel Welter

Michel Welter

Dr. Michel Welter was a Luxembourgian politician, and former leader of the Socialist Party. A member of Luxembourg's Chamber of Deputies, he served as the Director-General for Agriculture, Commerce, and Industry from 24 February 1916 until 3 January 1917, during the German occupation.He was one...

, and the liberal Léon Moutrier

Léon Moutrier

Léon Moutrier was a Luxembourgian politician and diplomat. A member of Luxembourg's Chamber of Deputies for the Liberal League, he served as the Director-General for the Interior and Public Information from 24 February 1916 until 3 January 1917, and for Justice and Public Information from that...

.

Food shortage

The most pressing concern of the Luxembourgian government was that of food supply. The war had made importation of food an impossibility, and the needs of the German occupiers inevitably came before those of the Luxembourgian people. To halt the deteriorating supply of food, Michel Welter, the Director-General for both agriculture and commerce, banned the export of food from Luxembourg. Furthermore, the government introduced rationingRationing

Rationing is the controlled distribution of scarce resources, goods, or services. Rationing controls the size of the ration, one's allotted portion of the resources being distributed on a particular day or at a particular time.- In economics :...

and price controls

Price controls

Price controls are governmental impositions on the prices charged for goods and services in a market, usually intended to maintain the affordability of staple foods and goods, and to prevent price gouging during shortages, or, alternatively, to insure an income for providers of certain goods...

to counteract the soaring demand and to make food more affordable for poorer Luxembourgers. However, the measures did not have the desired effect. Increasing numbers of Luxembourgers turned to the black market, and, to the consternation of the Luxembourgian government, the German army of occupation seemed to do little to help. Moreover, the government accused Germany of aiding the development of the black market by refusing to enforce regulations, and even of smuggling goods themselves.

Through 1916, the food crisis deepened, compounded by a poor potato

Potato

The potato is a starchy, tuberous crop from the perennial Solanum tuberosum of the Solanaceae family . The word potato may refer to the plant itself as well as the edible tuber. In the region of the Andes, there are some other closely related cultivated potato species...

harvest across all of the Low Countries; in neighbouring Belgium, the harvest was between 30% and 40% down on the previous year. Although many Luxembourgers were on near-starvation

Starvation

Starvation is a severe deficiency in caloric energy, nutrient and vitamin intake. It is the most extreme form of malnutrition. In humans, prolonged starvation can cause permanent organ damage and eventually, death...

level dietary intakes, the country managed to avoid famine

Famine

A famine is a widespread scarcity of food, caused by several factors including crop failure, overpopulation, or government policies. This phenomenon is usually accompanied or followed by regional malnutrition, starvation, epidemic, and increased mortality. Every continent in the world has...

. In part, this was due to a reduction of German soldiers' dependence upon local food sources, instead relying on imports from Germany.

Despite the avoidance of a famine, the Luxembourgian government lost much of the faith placed in it by the public and by the politicians. On 22 December 1916, Michel Welter, the minister responsible, was censured by the Chamber of Deputies, which demanded his resignation. Thorn procrastinated, seeking any option but firing the leader of one of three major parties, but could find none. On 3 January 1917, Welter was fired, and replaced by another socialist, Ernest Leclère

Ernest Leclère

Ernest Leclère was a Luxembourgian politician. A member of Luxembourg's Chamber of Deputies for the Socialist Party, he served two short stints as a minister during the German occupation during the First World War. His first position was as the Director-General for the Interior from 3 March 1915...

. Even after the change and von Tessmar's promise of his soldiers' better conduct in future, Léon Kauffmann was capable of citing thirty-six instances of German soldiers caught smuggling foodstuffs between March 1917 and June 1918.

Miners' strike

Trade union

A trade union, trades union or labor union is an organization of workers that have banded together to achieve common goals such as better working conditions. The trade union, through its leadership, bargains with the employer on behalf of union members and negotiates labour contracts with...

s springing up in both Luxembourg City and Esch-sur-Alzette

Esch-sur-Alzette

Esch-sur-Alzette is a commune with city status, in south-western Luxembourg. It is the country's second city, and its second-most populous commune, with a population of 29,853 people...

. Despite the war demand, iron production had slumped, leading to greater employment insecurity. In March and April, three independents

Independent (politician)

In politics, an independent or non-party politician is an individual not affiliated to any political party. Independents may hold a centrist viewpoint between those of major political parties, a viewpoint more extreme than any major party, or they may have a viewpoint based on issues that they do...

were elected as deputies from the canton of Esch-sur-Alzette

Esch-sur-Alzette (canton)

Esch-sur-Alzette is a canton in the south-west of Luxembourg, in Luxembourg District. The capital is Esch-sur-Alzette.The canton consists of the following 14 communes:*Bettembourg*Differdange*Dudelange*Esch-sur-Alzette*Frisange*Kayl*Leudelange...

, where the economy was dominated by iron and steel. As independents, these newly-elected deputies were the only legislative opposition

Opposition (parliamentary)

Parliamentary opposition is a form of political opposition to a designated government, particularly in a Westminster-based parliamentary system. Note that this article uses the term government as it is used in Parliamentary systems, i.e. meaning the administration or the cabinet rather than the state...

to the National Union Government.

For many Luxembourgers, particularly the miners, expression of disgust at the government could not be directed through the ballot box alone. Sensing the threat of civil disobedience or worse, von Tessmar threatened any individual committing an act of violence (in which he included strike action

Strike action

Strike action, also called labour strike, on strike, greve , or simply strike, is a work stoppage caused by the mass refusal of employees to work. A strike usually takes place in response to employee grievances. Strikes became important during the industrial revolution, when mass labour became...

) with the death penalty. However, on 31 May 1917, the workers sought to use their most potent weapon, by defying von Tessmar's ultimatum and downing tools. Germany was dependent upon Luxembourgian iron, as the British Royal Navy

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

's naval blockade

Blockade

A blockade is an effort to cut off food, supplies, war material or communications from a particular area by force, either in part or totally. A blockade should not be confused with an embargo or sanctions, which are legal barriers to trade, and is distinct from a siege in that a blockade is usually...

forced Germany to look to accessible local supplies; in 1916, Luxembourg produced over one-seventh of the Zollverein's pig iron

Pig iron

Pig iron is the intermediate product of smelting iron ore with a high-carbon fuel such as coke, usually with limestone as a flux. Charcoal and anthracite have also been used as fuel...

. As such, Germany simply could not afford a strike, lest it be deprived of critical raw materials.

In putting down the strike, von Tessmar was ruthlessly efficient, but he was not required to resort to the executions that he had threatened. Within nine days, the strike was defeated and the leaders arrested. The two ringleaders were then sentenced by German court-martial in Trier

Trier

Trier, historically called in English Treves is a city in Germany on the banks of the Moselle. It is the oldest city in Germany, founded in or before 16 BC....

to ten years imprisonment, to the disgust of the government. The continued refusal of the German authorities to respect the Luxembourgian government, and the humiliating manner in which the strike was put down by German military muscle rather than the Luxembourgian gendarmerie

Gendarmerie

A gendarmerie or gendarmery is a military force charged with police duties among civilian populations. Members of such a force are typically called "gendarmes". The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary describes a gendarme as "a soldier who is employed on police duties" and a "gendarmery, -erie" as...

, were too much for Thorn. On 19 June 1917, the government resigned.

Kauffmann government

Although the experiment in grand coalition had failed, the need for some political unity remained. As the National Union Government was collapsing, Kauffmann arranged an alliance between his Party of the Right and Moutrier's Liberal LeagueLiberal League (Luxembourg)

The Liberal League was a political party in Luxembourg between 1904 and 1925. It was the indirect predecessor of the Democratic Party , which has been one of the three major parties in Luxembourg since the Second World War....

, seeking to achieve change that would outlive the occupation. The primary objective was to address the perennial grievances of the left by amending the constitution; in November 1917, the Chamber of Deputies launched a wide-ranging series of debates on various amendments to the constitutions. Ultimately, the constitution was amended to prohibit the government from entering into secret treaties

Secret treaty

A secret treaty is a treaty between nations that is not revealed to other nations or interested observers. An example would be a secret alliance between two nations to support each other in the event of war...

, to improve deputies' pay (hitherto set at just 5 francs a day), to introduce universal suffrage

Universal suffrage

Universal suffrage consists of the extension of the right to vote to adult citizens as a whole, though it may also mean extending said right to minors and non-citizens...

, and to change the plurality

Plurality voting system

The plurality voting system is a single-winner voting system often used to elect executive officers or to elect members of a legislative assembly which is based on single-member constituencies...

voting system

Voting system

A voting system or electoral system is a method by which voters make a choice between options, often in an election or on a policy referendum....

to a proportional

Proportional representation

Proportional representation is a concept in voting systems used to elect an assembly or council. PR means that the number of seats won by a party or group of candidates is proportionate to the number of votes received. For example, under a PR voting system if 30% of voters support a particular...

one.

Whereas all of the above measures were broadly popular, across most of the political spectrum, the same was not true of the proposal to amend Article 32. Said article had not been amended in the overhaul of 1868, and its text had remained unchanged since the original constitution of 1848, stating unequivocally that all sovereignty

Sovereignty

Sovereignty is the quality of having supreme, independent authority over a geographic area, such as a territory. It can be found in a power to rule and make law that rests on a political fact for which no purely legal explanation can be provided...

resided in the person of the Grand Duchess. For some, particularly those that resented the close relations between Marie-Adélaïde and the German royalty, the idea of national sovereignty residing in such a person was unacceptable. The Chamber of Deputies voted to review Article 32, but Kauffmann refused to allow it, seeing the redefinition of the source of national sovereignty as covert republicanism

Republicanism

Republicanism is the ideology of governing a nation as a republic, where the head of state is appointed by means other than heredity, often elections. The exact meaning of republicanism varies depending on the cultural and historical context...

.

The summer of 1918 saw a dramatic decline in the fortunes of the government. On 8 July, Clausen

Clausen, Luxembourg

Clausen is a quarter in central Luxembourg City, in southern Luxembourg.In 2001, the quarter had a population of 886 people....

, in central Luxembourg City, had been bombed by the British Royal Air Force

Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force is the aerial warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Formed on 1 April 1918, it is the oldest independent air force in the world...

, killing ten civilians. Although this did not endear the Allies

Allies of World War I

The Entente Powers were the countries at war with the Central Powers during World War I. The members of the Triple Entente were the United Kingdom, France, and the Russian Empire; Italy entered the war on their side in 1915...

to Luxembourgers, the Grand Duchess' instinct was to run to the Germans, who were even less popular amongst the people. On 16 August, German Chancellor Georg von Hertling paid a visit to Luxembourg; although Hertling asked only to see the Grand Duchess, Kauffmann asked that he also attend. To the Luxembourgian people, relations between the two countries now seemed unambiguously cordial, and all that was left of Kauffmann's credibility disappeared. This was compounded further by the news on the 26 August of the engagement

Engagement

An engagement or betrothal is a promise to marry, and also the period of time between proposal and marriage which may be lengthy or trivial. During this period, a couple is said to be betrothed, affianced, engaged to be married, or simply engaged...

of Princess Antonia of Luxembourg to Rupprecht, Crown Prince of Bavaria

Rupprecht, Crown Prince of Bavaria

Rupprecht or Rupert, Crown Prince of Bavaria was the last Bavarian Crown Prince.His full title was His Royal Highness Rupprecht Maria Luitpold Ferdinand, Crown Prince of Bavaria, Duke of Bavaria, of Franconia and in Swabia, Count Palatine of the Rhine...

, who was Generalfeldmarschall

Generalfeldmarschall

Field Marshal or Generalfeldmarschall in German, was a rank in the armies of several German states and the Holy Roman Empire; in the Austrian Empire, the rank Feldmarschall was used...

in the German army. Pressure mounted on Kauffmann; with his party still strong, but with his personal reputation shattered, he was left with no option but to resign, which he did on 28 September in favour of Émile Reuter, another conservative.

Armistice

Spring Offensive

The 1918 Spring Offensive or Kaiserschlacht , also known as the Ludendorff Offensive, was a series of German attacks along the Western Front during World War I, beginning on 21 March 1918, which marked the deepest advances by either side since 1914...

had been an unmitigated disaster, whereas the Allied counter-attack

Counter-Attack

Counter-Attack is a 1945 war film starring Paul Muni and Marguerite Chapman as two Russians trapped in a collapsed building with seven enemy German soldiers during World War II...

, the Hundred Days Offensive

Hundred Days Offensive

The Hundred Days Offensive was the final period of the First World War, during which the Allies launched a series of offensives against the Central Powers on the Western Front from 8 August to 11 November 1918, beginning with the Battle of Amiens. The offensive forced the German armies to retreat...

, had driven Germany back towards its own borders. On 6 November, von Tessmar announced the full withdrawal of German soldiers from Luxembourg. Five days after von Tessmar's announcement, Germany signed an armistice treaty

Armistice with Germany (Compiègne)

The armistice between the Allies and Germany was an agreement that ended the fighting in the First World War. It was signed in a railway carriage in Compiègne Forest on 11 November 1918 and marked a victory for the Allies and a complete defeat for Germany, although not technically a surrender...

, which brought an end to the war of four years. One of the terms of the armistice involved the withdrawal of German soldiers from Luxembourg, along with the other occupied countries.

The Allied Powers agreed that the German withdrawal from Luxembourg would be observed by the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

, and that the USA would receive the honour of liberating the captive country. On 18 November, General John Pershing issued a proclamation

Proclamation

A proclamation is an official declaration.-England and Wales:In English law, a proclamation is a formal announcement , made under the great seal, of some matter which the King in Council or Queen in Council desires to make known to his or her subjects: e.g., the declaration of war, or state of...

to the people of Luxembourg, stating that the United States' newly-formed Third Army would move through Luxembourg to occupy the German Rhineland

Rhineland

Historically, the Rhinelands refers to a loosely-defined region embracing the land on either bank of the River Rhine in central Europe....

, but that the Americans would come as allies and as liberators:

Luc Housse

Jean-Pierre Lucas Housse , known as Luc Housse, was a Luxembourgian politician that served as Mayor of Luxembourg City between 1918 and 1920...

, the Mayor of Luxembourg City, told the advancing American army that the Germans had, on the whole, been disciplined and well-behaved in the previous three weeks: a marked improvement upon his numerous complaints earlier in the conflict. Finally, on 22 November 1918, the German army completed its withdrawal from Luxembourg, ending its occupation.

Germany's defeat created the perfect opportunity for the Allied powers to resolve the Luxembourgian question once and for all. By removing Luxembourg from Germany's sphere of influence

Sphere of influence

In the field of international relations, a sphere of influence is a spatial region or conceptual division over which a state or organization has significant cultural, economic, military or political influence....

, they hoped to guarantee its continued independence, and thus preserve the peace they had won. On 19 December, at the instigation of the British and French governments, the Luxembourgian government announced its withdrawal from the Zollverein

Zollverein

thumb|upright=1.2|The German Zollverein 1834–1919blue = Prussia in 1834 grey= Included region until 1866yellow= Excluded after 1866red = Borders of the German Union of 1828 pink= Relevant others until 1834...

and an end to the railway concessions that Luxembourg had previously granted Germany.

Rebellion

Although the Allies were satisfied at this remedy, at the time, the Luxembourgian government was threatened by a communist insurgency. After the retreat of the German army, revolutionaries established Russian-influenced Workers' councilWorkers' council

A workers' council, or revolutionary councils, is the phenomenon where a single place of work or enterprise, such as a factory, school, or farm, is controlled collectively by the workers of that workplace, through the core principle of temporary and instantly revocable delegates.In a system with...

s across Luxembourg. On 10 November, the day after Karl Liebknecht

Karl Liebknecht

was a German socialist and a co-founder with Rosa Luxemburg of the Spartacist League and the Communist Party of Germany. He is best known for his opposition to World War I in the Reichstag and his role in the Spartacist uprising of 1919...

and Rosa Luxemburg

Rosa Luxemburg

Rosa Luxemburg was a Marxist theorist, philosopher, economist and activist of Polish Jewish descent who became a naturalized German citizen...

declared a similar 'socialist republic' in Germany, communists in Luxembourg City declared a republic, but it lasted for only a matter of hours. Another revolt took place in Esch-sur-Alzette

Esch-sur-Alzette

Esch-sur-Alzette is a commune with city status, in south-western Luxembourg. It is the country's second city, and its second-most populous commune, with a population of 29,853 people...

in the early hours of 11 November, but also failed. The socialists had been fired up by the behaviour of Grand Duchess Marie-Adélaïde, whose interventionist and obstructive streak had stymied even Eyschen. On 12 November, socialist and liberal politicians, finding their old commonality on the issue, called for her abdication

Abdication

Abdication occurs when a monarch, such as a king or emperor, renounces his office.-Terminology:The word abdication comes derives from the Latin abdicatio. meaning to disown or renounce...

. A motion in the Chamber of Deputies

Chamber of Deputies of Luxembourg

The Chamber of Deputies , abbreviated to the Chamber, is the unicameral national legislature of Luxembourg. 'Krautmaart' is sometimes used as a metonym for the Chamber, after the square on which the Hôtel de la Chambre is located....

demanding the abolition of the monarchy was defeated by 21 votes to 19 (with 3 abstentions), but the Chamber did demand the government hold a popular referendum

Referendum

A referendum is a direct vote in which an entire electorate is asked to either accept or reject a particular proposal. This may result in the adoption of a new constitution, a constitutional amendment, a law, the recall of an elected official or simply a specific government policy. It is a form of...

on the issue.

Although the left's early attempts at founding a republic had failed, the underlying cause of the resentment had not been addressed, and, as long as Marie-Adélaïde was Grand Duchess, the liberals would ally themselves to the socialists in opposition to her. The French government also refused to cooperate with a government led by a so-called 'collaborator

Collaborationism

Collaborationism is cooperation with enemy forces against one's country. Legally, it may be considered as a form of treason. Collaborationism may be associated with criminal deeds in the service of the occupying power, which may include complicity with the occupying power in murder, persecutions,...

'; French Foreign Minister

Minister of Foreign Affairs (France)

Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs ), is France's foreign affairs ministry, with the headquarters located on the Quai d'Orsay in Paris close to the National Assembly of France. The Minister of Foreign and European Affairs in the government of France is the cabinet minister responsible for...

Stéphen Pichon

Stéphen Pichon

Stéphen Pichon was a French politician of the Third Republic. He served as French Minister to China , including the period of the Boxer Uprising...

called cooperation 'a grave compromise with the enemies of France'. More pressing than either of these troubles, on 9 January, a company

Company (military unit)

A company is a military unit, typically consisting of 80–225 soldiers and usually commanded by a Captain, Major or Commandant. Most companies are formed of three to five platoons although the exact number may vary by country, unit type, and structure...

of the Luxembourgian army rebelled, declaring itself to be the army of the new republic, with Émile Servais

Émile Servais

Émile Servais was a Luxembourgian left liberal politician. He was an engineer by profession.On 9 January 1919, a company of the Luxembourgian army revolted against the Grand Duchess Marie-Adélaïde, and declared itself to be the army of a new socialist republic...

(the son of Emmanuel Servais

Emmanuel Servais

Lambert Joseph Emmanuel Servais was a Luxembourgian politician. He held numerous offices of national importance, foremost amongst which was in serving as the fifth Prime Minister of Luxembourg, for seven years, from 3 December 1867 until 26 December 1874.After being Prime Minister, he was a...

) as 'Chairman of the Committee of Public Safety'. However, by January, the vacuum left by the German withdrawal had been filled by American and French soldiers. President of the Chamber François Altwies

François Altwies

François Altwies was a Luxembourgian politician. He sat in the Chamber of Deputies, of which he served as President from 1917 until 1925....

asked French troops to intervene. Eager to put an end to what it perceived to be pro-Belgian revolutions, the French army crushed the would-be revolutionaries.

Nonetheless, the disloyalty shown by her own armed forces was too much for Marie-Adélaïde, who abdicated in favour of her sister, Charlotte

Charlotte, Grand Duchess of Luxembourg

Charlotte, Grand Duchess of Luxembourg was the reigning Grand Duchess of Luxembourg from 1919 to 1964.-Early life and life as Grand Duchess:...

. Belgium

Belgium

Belgium , officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a federal state in Western Europe. It is a founding member of the European Union and hosts the EU's headquarters, and those of several other major international organisations such as NATO.Belgium is also a member of, or affiliated to, many...

, which had hoped to either annex Luxembourg or force it into personal union

Personal union

A personal union is the combination by which two or more different states have the same monarch while their boundaries, their laws and their interests remain distinct. It should not be confused with a federation which is internationally considered a single state...

, grudgingly recognised Charlotte on 13 February. The dynasty's hold on power would be tenuous until September 1919, when a referendum on the future of the Grand Duchy found 77.8% in favour of continued rule by the House of Nassau-Weilburg.

Paris Peace Conference

Despite the armistice ending the war, and the end of the revolts, Luxembourg's own future was still uncertain. Belgium was one of the countries hit hardest by the war; almost the whole of the country was occupied by Germany, and over 43,000 Belgians, including 30,000 civilians, had died as a result. Belgium sought compensation, and had its eye on any and all of its neighbours; in November 1918, Lord HardingeCharles Hardinge, 1st Baron Hardinge of Penshurst

Charles Hardinge, 1st Baron Hardinge of Penshurst, was a British diplomat and statesman who served as Viceroy of India from 1910 to 1916.-Background and education:...

, the Permanent Secretary

Permanent Secretary

The Permanent secretary, in most departments officially titled the permanent under-secretary of state , is the most senior civil servant of a British Government ministry, charged with running the department on a day-to-day basis...

at the Foreign Office, told the Dutch

Netherlands

The Netherlands is a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, located mainly in North-West Europe and with several islands in the Caribbean. Mainland Netherlands borders the North Sea to the north and west, Belgium to the south, and Germany to the east, and shares maritime borders...

ambassador in London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

, "The Belgians are on the make, and they want to grab whatever they can."

Propaganda

Propaganda is a form of communication that is aimed at influencing the attitude of a community toward some cause or position so as to benefit oneself or one's group....

campaign to promote its vision of annexation. At the Paris Peace Conference

Paris Peace Conference, 1919

The Paris Peace Conference was the meeting of the Allied victors following the end of World War I to set the peace terms for the defeated Central Powers following the armistices of 1918. It took place in Paris in 1919 and involved diplomats from more than 32 countries and nationalities...

, the Belgian delegation argued in favour of the international community

International community

The international community is a term used in international relations to refer to all peoples, cultures and governments of the world or to a group of them. The term is used to imply the existence of common duties and obligations between them...

allowing Belgium to annex Luxembourg. However, fearing loss of influence over the left bank of the Rhine, France rejected Belgium's overtures out of hand, thus guaranteeing Luxembourg's continued independence.

The resulting Treaty of Versailles

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was one of the peace treaties at the end of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1919, exactly five years after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The other Central Powers on the German side of...

set aside two articles (§40 and §41) to address concerns for Luxembourg's status. The main article, §40, revoked all special privileges that Germany had acquired in Luxembourg, with Germany specifically renouncing advantages gained in the treaties of 1842, 1847, 1865, 1866, February 1867, May 1867

Treaty of London, 1867

The Treaty of London , often called the Second Treaty of London after the 1839 Treaty, was an international treaty signed on 11 May 1867. Agreed in the aftermath of the Austro-Prussian War and the Luxembourg Crisis, it had wide-reaching consequences for Luxembourg and for relations between...

, 1871

Treaty of Frankfurt (1871)

The Treaty of Frankfurt was a peace treaty signed in Frankfurt on 10 May 1871, at the end of the Franco-Prussian War.- Summary :The treaty did the following:...

, 1872, and 1902. The effects of these treaties' revocation were then explicitly stated; Luxembourg would withdraw from the Zollverein, Germany would lose its right to use the Luxembourgian railways, and Germany was obligated to recognise the termination of Luxembourg's neutrality, thus validating the actions of the Luxembourgian government since the armistice. Furthermore, to prevent economic embargo

Embargo

An embargo is the partial or complete prohibition of commerce and trade with a particular country, in order to isolate it. Embargoes are considered strong diplomatic measures imposed in an effort, by the imposing country, to elicit a given national-interest result from the country on which it is...

after the end of the customs union, the treaty allowed Luxembourg an indefinite option on German coal

Coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock usually occurring in rock strata in layers or veins called coal beds or coal seams. The harder forms, such as anthracite coal, can be regarded as metamorphic rock because of later exposure to elevated temperature and pressure...

, and prohibited Germany from levying duty on Luxembourgian exports until 1924.

Luxembourgers overseas

French Army

The French Army, officially the Armée de Terre , is the land-based and largest component of the French Armed Forces.As of 2010, the army employs 123,100 regulars, 18,350 part-time reservists and 7,700 Legionnaires. All soldiers are professionals, following the suspension of conscription, voted in...

, of whom over 2,000 died. As Luxembourg's pre-war population was only 266,000, the loss of life solely in the service of the French army amounted to almost 1% of the entire Luxembourgian population, relatively greater than the totals for many combatant countries (see: World War I casualties

World War I casualties

The total number of military and civilian casualties in World War I were over 35 million. There were over 15 million deaths and 20 million wounded ranking it among the deadliest conflicts in human history....

). The Luxembourgian volunteers are commemorated by the Gëlle Fra

Gëlle Fra

The Monument of Remembrance , usually known by the nickname of the Gëlle Fra , is a war memorial in Luxembourg City, in southern Luxembourg...

(literally 'Golden Lady' ) war memorial

War memorial

A war memorial is a building, monument, statue or other edifice to celebrate a war or victory, or to commemorate those who died or were injured in war.-Historic usage:...

, which was unveiled in Luxembourg City on 27 May 1923. The original memorial was destroyed on 20 October 1940, during the Nazi occupation

German occupation of Luxembourg in World War II

The German occupation of Luxembourg in World War II was the period in the history of Luxembourg after it was used as a transit territory to attack France by outflanking the Maginot Line. Plans for the attack had been prepared by 9 October 1939, but execution was postponed several times...

, as it symbolised the rejection of German identity and active resistance against Germanisation

Germanisation

Germanisation is both the spread of the German language, people and culture either by force or assimilation, and the adaptation of a foreign word to the German language in linguistics, much like the Romanisation of many languages which do not use the Latin alphabet...

. After World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, it was gradually rebuilt, culminating in its second unveiling, on 23 June 1985.

The Luxembourgian community

Luxembourg American

Luxembourgian Americans, also known as Luxembourg Americans , are citizens of the United States of Luxembourgian ancestry...

in the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

found itself confronted by a crisis of identity

Identity crisis (psychology)

"Identity crisis is the failure to achieve ego identity during adolescence." The term was coined by the psychologist Erik Erikson. The stage of psychosocial development in which identity crisis may occur is called the Identity Cohesion versus Role Confusion stage...

. Traditionally, they had identified themselves as ethnically German, rather than as a separate community of their own. As such, they read German language

German language

German is a West Germanic language, related to and classified alongside English and Dutch. With an estimated 90 – 98 million native speakers, German is one of the world's major languages and is the most widely-spoken first language in the European Union....

newspapers, attended German schools, and lived amongst German American

German American

German Americans are citizens of the United States of German ancestry and comprise about 51 million people, or 17% of the U.S. population, the country's largest self-reported ancestral group...

s. Nonetheless, when it became apparent that the war would not be over quickly, the opinions of Luxembourg Americans changed; on 2 May 1915, the Luxemburger Brotherhood of America's annual convention decided to adopt English

English language

English is a West Germanic language that arose in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of England and spread into what was to become south-east Scotland under the influence of the Anglian medieval kingdom of Northumbria...

as its only official language. Other organisations were less inclined to change their ways; the Luxemburger Gazette opposed President

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

Woodrow Wilson

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson was the 28th President of the United States, from 1913 to 1921. A leader of the Progressive Movement, he served as President of Princeton University from 1902 to 1910, and then as the Governor of New Jersey from 1911 to 1913...

's supposed 'favouritism' towards the United Kingdom as late in the war as 1917. However, when the United States entered the war in April of that year, the wavering members of the community supported the Allies, changing forever the relationship between the German and Luxembourgian communities in the USA.

Footnotes

- Links to many of the cited primary sources, including speeches, telegrams, and despatches, can be found in the 'References' section.