Gilbert Ledward

Encyclopedia

Royal Academy

The Royal Academy of Arts is an art institution based in Burlington House on Piccadilly, London. The Royal Academy of Arts has a unique position in being an independent, privately funded institution led by eminent artists and architects whose purpose is to promote the creation, enjoyment and...

(23 January 1888 – 21 June 1960), was an English sculptor.

He won the Prix de Rome

Prix de Rome

The Prix de Rome was a scholarship for arts students, principally of painting, sculpture, and architecture. It was created, initially for painters and sculptors, in 1663 in France during the reign of Louis XIV. It was an annual bursary for promising artists having proved their talents by...

for sculpture in 1913, and in World War I served in the Royal Garrison Artillery

Royal Garrison Artillery

The Royal Garrison Artillery was an arm of the Royal Artillery that was originally tasked with manning the guns of the British Empire's forts and fortresses, including coastal artillery batteries, the heavy gun batteries attached to each infantry division, and the guns of the siege...

and later as a war artist

War artist

A war artist depicts some aspect of war through art; this might be a pictorial record or it might commemorate how "war shapes lives." War artists have explored a visual and sensory dimension of war which is often absent in written histories or other accounts of warfare.- Definition and context:A...

. He was professor of sculpture at the Royal College of Art

Royal College of Art

The Royal College of Art is an art school located in London, United Kingdom. It is the world’s only wholly postgraduate university of art and design, offering the degrees of Master of Arts , Master of Philosophy and Doctor of Philosophy...

and in 1937 was elected a Royal Academician. He became president of the Royal Society of British Sculptors and a trustee of the Royal Academy

Royal Academy

The Royal Academy of Arts is an art institution based in Burlington House on Piccadilly, London. The Royal Academy of Arts has a unique position in being an independent, privately funded institution led by eminent artists and architects whose purpose is to promote the creation, enjoyment and...

.

Early life

Born in Chelsea, LondonChelsea, London

Chelsea is an area of West London, England, bounded to the south by the River Thames, where its frontage runs from Chelsea Bridge along the Chelsea Embankment, Cheyne Walk, Lots Road and Chelsea Harbour. Its eastern boundary was once defined by the River Westbourne, which is now in a pipe above...

, Ledward was the third of the four children of Richard Arthur Ledward (1857–1890), a sculptor, by his marriage to Mary Jane Wood. His grandfather, Richard Perry Ledward, had been a Staffordshire

Staffordshire

Staffordshire is a landlocked county in the West Midlands region of England. For Eurostat purposes, the county is a NUTS 3 region and is one of four counties or unitary districts that comprise the "Shropshire and Staffordshire" NUTS 2 region. Part of the National Forest lies within its borders...

master potter with the firm of Pinder, Bourne & Co. of Burslem

Burslem

The town of Burslem, known as the Mother Town, is one of the six towns that amalgamated to form the current city of Stoke-on-Trent, in the ceremonial county of Staffordshire, in the Midlands of England.-Topography:...

. His father died when Ledward was only two. He was educated at St Mark's College, Chelsea until 1901, when his mother took the family to live in Germany

German Empire

The German Empire refers to Germany during the "Second Reich" period from the unification of Germany and proclamation of Wilhelm I as German Emperor on 18 January 1871, to 1918, when it became a federal republic after defeat in World War I and the abdication of the Emperor, Wilhelm II.The German...

. In 1905 Ledward began to train as a sculptor at the Royal College of Art

Royal College of Art

The Royal College of Art is an art school located in London, United Kingdom. It is the world’s only wholly postgraduate university of art and design, offering the degrees of Master of Arts , Master of Philosophy and Doctor of Philosophy...

under Edouard Lantéri

Edouard Lanteri

Edouard Lanteri was a sculptor and medallist whose romantic French style of sculpting was seen as influential among exponents of New Sculpture.-Life history:...

, and in November 1910 he proceeded to the Royal Academy Schools.

Career

In 1913 Ledward won both the Prix de RomePrix de Rome

The Prix de Rome was a scholarship for arts students, principally of painting, sculpture, and architecture. It was created, initially for painters and sculptors, in 1663 in France during the reign of Louis XIV. It was an annual bursary for promising artists having proved their talents by...

scholarship for sculpture and the Royal Academy

Royal Academy

The Royal Academy of Arts is an art institution based in Burlington House on Piccadilly, London. The Royal Academy of Arts has a unique position in being an independent, privately funded institution led by eminent artists and architects whose purpose is to promote the creation, enjoyment and...

's travelling award and gold medal. During the summer of 1914, he travelled throughout Italy, producing sketchbooks now held by the Royal Academy of Arts, but his travels were ended by the outbreak of the Great War

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

at the end of August. He was commissioned into the Royal Garrison Artillery

Royal Garrison Artillery

The Royal Garrison Artillery was an arm of the Royal Artillery that was originally tasked with manning the guns of the British Empire's forts and fortresses, including coastal artillery batteries, the heavy gun batteries attached to each infantry division, and the guns of the siege...

and was later mentioned in despatches. In 1917 he was fighting in Italy, and in April 1918 he was recalled to England, to be seconded to the Ministry of Information as a war artist

War artist

A war artist depicts some aspect of war through art; this might be a pictorial record or it might commemorate how "war shapes lives." War artists have explored a visual and sensory dimension of war which is often absent in written histories or other accounts of warfare.- Definition and context:A...

. He produced reliefs for the Imperial War Museum

Imperial War Museum

Imperial War Museum is a British national museum organisation with branches at five locations in England, three of which are in London. The museum was founded during the First World War in 1917 and intended as a record of the war effort and sacrifice of Britain and her Empire...

, generally of soldiers in action.

After the war, he was greatly in demand as a sculptor of war memorial

War memorial

A war memorial is a building, monument, statue or other edifice to celebrate a war or victory, or to commemorate those who died or were injured in war.-Historic usage:...

s. From 1927 to 1929 he was professor of sculpture at the Royal College of Art.

In 1934 he established a company called 'Sculptured Memorials and Headstones', which promoted better design of memorials in English churchyards. The firm's supporters included Eric Gill

Eric Gill

Arthur Eric Rowton Gill was a British sculptor, typeface designer, stonecutter and printmaker, who was associated with the Arts and Crafts movement...

and Edwin Lutyens

Edwin Lutyens

Sir Edwin Landseer Lutyens, OM, KCIE, PRA, FRIBA was a British architect who is known for imaginatively adapting traditional architectural styles to the requirements of his era...

.

In 1937 Ledward was elected a Royal Academician, having been an associate of the Royal Academy since 1932. He was seen as loyal to the values of the Academy, a defender of its academic traditions, but also ready to support good modern work. From 1954 to 1956 he was president of the Royal Society of British Sculptors and in 1956 was appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire

Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is an order of chivalry established on 4 June 1917 by George V of the United Kingdom. The Order comprises five classes in civil and military divisions...

. In 1956 he became a trustee of the Royal Academy.

Work

Eric Gill

Arthur Eric Rowton Gill was a British sculptor, typeface designer, stonecutter and printmaker, who was associated with the Arts and Crafts movement...

and less radical than Jagger

Charles Sargeant Jagger

Charles Sargeant Jagger MC was a British sculptor who, following active service in the First World War, sculpted many works on the theme of war...

, and was seen as representing the sculptural establishment

The Establishment

The Establishment is a term used to refer to a visible dominant group or elite that holds power or authority in a nation. The term suggests a closed social group which selects its own members...

.

In 1913 he gained his first major commission, a stone calvary

Calvary (sculpture)

A calvary is a type of monumental public crucifix, sometimes encased in an open shrine, most commonly found across northern France from Brittany east and through Belgium and equally familiar as wayside structures provided with minimal sheltering roofs in Italy and Spain...

for the church of Bourton-on-the-Water

Bourton-on-the-Water

Bourton-on-the-Water is a village and civil parish in Gloucestershire, England that lies on a wide flat vale within the Cotswolds Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty...

. An early figure in bronze

Bronze

Bronze is a metal alloy consisting primarily of copper, usually with tin as the main additive. It is hard and brittle, and it was particularly significant in antiquity, so much so that the Bronze Age was named after the metal...

, called Awakening, can be seen in a garden on the Chelsea Embankment

Chelsea Embankment

Chelsea Embankment is part of the Thames Embankment, a road and walkway along the north bank of the River Thames in central London, England.The western end of Chelsea Embankment, including a stretch of Cheyne Walk, is in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea; the eastern end, including...

.

Ledward's commissions for war memorial

War memorial

A war memorial is a building, monument, statue or other edifice to celebrate a war or victory, or to commemorate those who died or were injured in war.-Historic usage:...

s after the Great War of 1914 to 1918 included the Guards Division

Guards Division

The Guards Division is an administrative unit of the British Army responsible for the administration of the regiments of Foot Guards and the London Regiment.-Introduction:...

memorial in St. James's Park

St. James's Park

St. James's Park is a 23 hectare park in the City of Westminster, central London - the oldest of the Royal Parks of London. The park lies at the southernmost tip of the St. James's area, which was named after a leper hospital dedicated to St. James the Less.- Geographical location :St. James's...

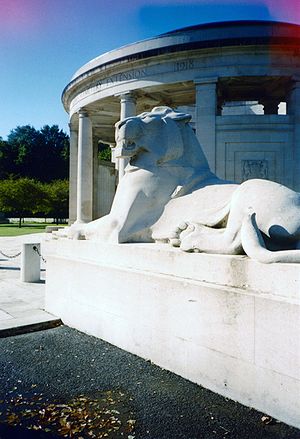

, London, two lions for the Memorial to the Missing

Ploegsteert Memorial to the Missing

The Ploegsteert Memorial to the Missing is a Commonwealth War Graves Commission memorial for the missing soldiers of World War I who fought in the immediate area of the Ypres Salient on the Western Front.The grounds were assigned to the United Kingdom in perpetuity by King Albert I of Belgium in...

at Ploegsteert

Ploegsteert

Ploegsteert is a village in Belgium located in the municipality of Comines-Warneton in the Hainaut province. It is approximately 2 kilometres north of the French border. Created in 1850 on part of the territory of Warneton, it includes the hamlet of Le Bizet....

, commissioned by the Imperial War Graves Commission, and war memorials at Stockport

Stockport

Stockport is a town in Greater Manchester, England. It lies on elevated ground southeast of Manchester city centre, at the point where the rivers Goyt and Tame join and create the River Mersey. Stockport is the largest settlement in the metropolitan borough of the same name...

, Abergavenny

Abergavenny

Abergavenny , meaning Mouth of the River Gavenny, is a market town in Monmouthshire, Wales. It is located 15 miles west of Monmouth on the A40 and A465 roads, 6 miles from the English border. Originally the site of a Roman fort, Gobannium, it became a medieval walled town within the Welsh Marches...

, Blackpool

Blackpool

Blackpool is a borough, seaside town, and unitary authority area of Lancashire, in North West England. It is situated along England's west coast by the Irish Sea, between the Ribble and Wyre estuaries, northwest of Preston, north of Liverpool, and northwest of Manchester...

, Harrogate

Harrogate

Harrogate is a spa town in North Yorkshire, England. The town is a tourist destination and its visitor attractions include its spa waters, RHS Harlow Carr gardens, and Betty's Tea Rooms. From the town one can explore the nearby Yorkshire Dales national park. Harrogate originated in the 17th...

, and Stonyhurst College

Stonyhurst College

Stonyhurst College is a Roman Catholic independent school, adhering to the Jesuit tradition. It is located on the Stonyhurst Estate near the village of Hurst Green in the Ribble Valley area of Lancashire, England, and occupies a Grade I listed building...

(1920), the last of which took the form of a marble

Marble

Marble is a metamorphic rock composed of recrystallized carbonate minerals, most commonly calcite or dolomite.Geologists use the term "marble" to refer to metamorphosed limestone; however stonemasons use the term more broadly to encompass unmetamorphosed limestone.Marble is commonly used for...

altar relief (pictured). Between 1922 and 1925, in partnership with H. Chalton Bradshaw, he created the bronze sculptures for the Household Division

Household Division

Household Division is a term used principally in the Commonwealth of Nations to describe a country’s most elite or historically senior military units, or those military units that provide ceremonial or protective functions associated directly with the head of state.-Historical Development:In...

's memorial on Horse Guards Parade

Horse Guards Parade

Horse Guards Parade is a large parade ground off Whitehall in central London, at grid reference . It is the site of the annual ceremonies of Trooping the Colour, which commemorates the monarch's official birthday, and Beating Retreat.-History:...

, Westminster

Westminster

Westminster is an area of central London, within the City of Westminster, England. It lies on the north bank of the River Thames, southwest of the City of London and southwest of Charing Cross...

. To the same period belongs his neoclassical

Neoclassical sculpture

Neoclassical sculpture was a sculptural style of the 18th and 19th centuries. The neoclassical period was one of the great ages of public sculpture, though its "classical" prototypes were more likely to be Roman copies of Hellenistic sculptures. The neoclassical sculptors paid homage to an idea of...

marble figure of Britannia

Britannia

Britannia is an ancient term for Great Britain, and also a female personification of the island. The name is Latin, and derives from the Greek form Prettanike or Brettaniai, which originally designated a collection of islands with individual names, including Albion or Great Britain. However, by the...

for the Hall of Memory at Stockport

Stockport

Stockport is a town in Greater Manchester, England. It lies on elevated ground southeast of Manchester city centre, at the point where the rivers Goyt and Tame join and create the River Mersey. Stockport is the largest settlement in the metropolitan borough of the same name...

.

George V of the United Kingdom

George V was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 through the First World War until his death in 1936....

for Kampala

Kampala

Kampala is the largest city and capital of Uganda. The city is divided into five boroughs that oversee local planning: Kampala Central Division, Kawempe Division, Makindye Division, Nakawa Division and Lubaga Division. The city is coterminous with Kampala District.-History: of Buganda, had chosen...

, Uganda

Uganda

Uganda , officially the Republic of Uganda, is a landlocked country in East Africa. Uganda is also known as the "Pearl of Africa". It is bordered on the east by Kenya, on the north by South Sudan, on the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, on the southwest by Rwanda, and on the south by...

, in 1939, and for Nairobi

Nairobi

Nairobi is the capital and largest city of Kenya. The city and its surrounding area also forms the Nairobi County. The name "Nairobi" comes from the Maasai phrase Enkare Nyirobi, which translates to "the place of cool waters". However, it is popularly known as the "Green City in the Sun" and is...

, Kenya

Kenya

Kenya , officially known as the Republic of Kenya, is a country in East Africa that lies on the equator, with the Indian Ocean to its south-east...

, in 1940, and another of King George VI

George VI of the United Kingdom

George VI was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until his death...

for Hong Kong

Hong Kong

Hong Kong is one of two Special Administrative Regions of the People's Republic of China , the other being Macau. A city-state situated on China's south coast and enclosed by the Pearl River Delta and South China Sea, it is renowned for its expansive skyline and deep natural harbour...

in 1947. His portrait busts in marble

Marble

Marble is a metamorphic rock composed of recrystallized carbonate minerals, most commonly calcite or dolomite.Geologists use the term "marble" to refer to metamorphosed limestone; however stonemasons use the term more broadly to encompass unmetamorphosed limestone.Marble is commonly used for...

include those of Bishop de Labilliere

Paul de Labilliere

Paul Fulcrand Delacour Labilliere was the second Bishop of Knaresborough from 1934 to 1938; and, subsequently, Dean of Westminster. Born on 22 January 1879 into a legal family he was educated at Harrow and Merton College, Oxford. After taking Holy Orders he became Chaplain to the Bishop of...

(1944), the actress Rachel Gurney

Rachel Gurney

Rachel Gurney was an English actress. She began her career in the theatre towards the end of World War II and then expanded into television and film in the 1950s. She remained active mostly in television and theatre work through the early 1990s...

(1945), and Admiral Sir Martin Dunbar-Nasmith VC (1947). His war memorials after the Second World War include one in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey

The Collegiate Church of St Peter at Westminster, popularly known as Westminster Abbey, is a large, mainly Gothic church, in the City of Westminster, London, United Kingdom, located just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is the traditional place of coronation and burial site for English,...

to the Submarine Service, Commandos, and Airborne Forces (1948).

Ledward designed the bronze figures of St Nicholas

Saint Nicholas

Saint Nicholas , also called Nikolaos of Myra, was a historic 4th-century saint and Greek Bishop of Myra . Because of the many miracles attributed to his intercession, he is also known as Nikolaos the Wonderworker...

and St Christopher

Saint Christopher

.Saint Christopher is a saint venerated by Roman Catholics and Orthodox Christians, listed as a martyr killed in the reign of the 3rd century Roman Emperor Decius or alternatively under the Roman Emperor Maximinus II Dacian...

at the Hospital for Sick Children

Hospital for Sick Children

The Hospital for Sick Children – is a major paediatric centre for the Greater Toronto Area, serving patients up to age 18. Located on University Avenue in Downtown Toronto, SickKids is part of the city’s Discovery District, a critical mass of scientists and entrepreneurs who are focused on...

in Great Ormond Street (1952), the fountain in Sloane Square

Sloane Square

Sloane Square is a small hard-landscaped square on the boundaries of the fashionable London districts of Knightsbridge, Belgravia and Chelsea, located southwest of Charing Cross, in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. The square is part of the Hans Town area designed in 1771 by Henry...

(1953), the new Great Seal of the Realm

Great Seal of the Realm

The Great Seal of the Realm or Great Seal of the United Kingdom is a seal that is used to symbolise the Sovereign's approval of important state documents...

of 1953 and the 1953 crown for the coronation

Coronation

A coronation is a ceremony marking the formal investiture of a monarch and/or their consort with regal power, usually involving the placement of a crown upon their head and the presentation of other items of regalia...

of Elizabeth II, of which more than five million were minted. In 1957, he created a memorial to the second Duke of Westminster

Hugh Grosvenor, 2nd Duke of Westminster

Hugh Richard Arthur Grosvenor, 2nd Duke of Westminster GCVO DSO was the son of Victor Alexander Grosvenor, Earl Grosvenor and Lady Sibell Mary Lumley, the daughter of the 9th Earl of Scarborough...

in St Mary's Church, Eccleston

St Mary's Church, Eccleston

St Mary's Church, Eccleston, is in the village of Eccleston, Cheshire, England, on the estate of the Duke of Westminster south of Chester. The church is designated by English Heritage as a Grade I listed building. It is an active Anglican parish church in the diocese of Chester, the...

, Cheshire

Cheshire

Cheshire is a ceremonial county in North West England. Cheshire's county town is the city of Chester, although its largest town is Warrington. Other major towns include Widnes, Congleton, Crewe, Ellesmere Port, Runcorn, Macclesfield, Winsford, Northwich, and Wilmslow...

. His last work was a stone frieze

Frieze

thumb|267px|Frieze of the [[Tower of the Winds]], AthensIn architecture the frieze is the wide central section part of an entablature and may be plain in the Ionic or Doric order, or decorated with bas-reliefs. Even when neither columns nor pilasters are expressed, on an astylar wall it lies upon...

with the title Vision and Imagination for Barclays Bank in Old Broad Street, City of London

City of London

The City of London is a small area within Greater London, England. It is the historic core of London around which the modern conurbation grew and has held city status since time immemorial. The City’s boundaries have remained almost unchanged since the Middle Ages, and it is now only a tiny part of...

. Wnen the building was demolished in 1995, the frieze was saved from destruction by the Public Monuments and Sculpture Association

Public Monuments and Sculpture Association

The Public Monuments and Sculpture Association, or PMSA, was established in 1991 to bring together individuals and organisations with an interest in public sculptures and monuments, their production, preservation and history....

.

Marriage and death

In 1911, Ledward married Margery Beatrix Cheesman, and they later had two daughters and a son.He was a member of the Chelsea Arts Club

Chelsea Arts Club

The Chelsea Arts Club is a private members club located in London with a membership of over 2,400, including artists, poets, architects, writers, dancers, actors, musicians, photographers, and filmmakers...

and in Who's Who

Who's Who (UK)

Who's Who is an annual British publication of biographies which vary in length of about 30,000 living notable Britons.-History:...

gave his recreation as sailing

Sailing

Sailing is the propulsion of a vehicle and the control of its movement with large foils called sails. By changing the rigging, rudder, and sometimes the keel or centre board, a sailor manages the force of the wind on the sails in order to move the boat relative to its surrounding medium and...

. He died at number 31, Queen's Gate

Queen's Gate

Queen's Gate is a major street in South Kensington, London, England. It runs from Kensington Road south, intersecting with Cromwell Road, and then on to Old Brompton Road....

, London, on 21 June 1960.