Gulliver's Travels

Encyclopedia

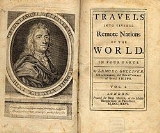

Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World, in Four Parts. By Lemuel Gulliver, First a Surgeon, and then a Captain of Several Ships, better known simply as Gulliver's Travels (1726, amended 1735), is a novel by Anglo-Irish

writer and clergyman Jonathan Swift

(also known as Dean Swift) that is both a satire

on human nature and a parody

of the "travellers' tales" literary sub-genre. It is Swift's best known full-length work, and a classic of English literature

.

The book became popular as soon as it was published (John Gay

said in a 1726 letter to Swift that "it is universally read, from the cabinet council to the nursery"); since then, it has never been out of print.

4 May 1699 — 13 April 1702

4 May 1699 — 13 April 1702

The book begins with a very short preamble in which Lemuel Gulliver

, in the style of books of the time, gives a brief outline of his life and history prior to his voyages. He enjoys travelling, although it is that love of travel that is his downfall.

During his first voyage, Gulliver is washed ashore after a shipwreck and finds himself a prisoner of a race of tiny people, less than 6 inches high, who are inhabitants of the island country of Lilliput. After giving assurances of his good behaviour, he is given a residence in Lilliput and becomes a favourite of the court. From there, the book follows Gulliver's observations on the Court of Lilliput. He is also given the permission to roam around the city on a condition he not harm their subjects. Gulliver assists the Lilliputians to subdue their neighbours, the Blefuscidians, by stealing their fleet. However, he refuses to reduce the island nation of Blefuscu to a province of Lilliput, displeasing the King and the court. Gulliver is charged with treason and sentenced to be blinded. With the assistance of a kind friend, Gulliver escapes to Blefuscu, where he spots and retrieves an abandoned boat and sails out to be rescued by a passing ship which safely takes him back home.

This book of the Travels is a topical political satire (see below).

20 June 1702 — 3 June 1706

20 June 1702 — 3 June 1706

When the sailing ship Adventure is steered off course by storms and forced to go in to land for want of fresh water, Gulliver is abandoned by his companions and found by a farmer who is 72 feet (21.9 m) tall (the scale of Lilliput is approximately 1:12; of Brobdingnag

12:1, judging from Gulliver estimating a man's step being 10 yards (9.1 m)). He brings Gulliver home and his daughter cares for Gulliver. The farmer treats him as a curiosity and exhibits him for money. The word gets out and the Queen of Brobdingnag wants to see the show. She loves Gulliver and he is then bought by her and kept as a favourite at court.

Since Gulliver is too small to use their huge chairs, beds, knives and forks, the queen commissions a small house to be built for Gulliver so that he can be carried around in it. This is referred to as his "travelling box." In between small adventures such as fighting giant wasps and being carried to the roof by a monkey, he discusses the state of Europe with the King. The King is not happy with Gulliver's accounts of Europe, especially upon learning of the use of guns and cannons. On a trip to the seaside, his travelling box is seized by a giant eagle which drops Gulliver and his box right into the sea where he is picked up by some sailors, who return him to England.

This book compares the truly moral man to the representative man, the latter of whom is clearly shown to be the lesser of the two; Swift, being in Anglican holy orders, was likely to make such comparisons.

After Gulliver's ship is attacked by pirates, he is maroon

ed close to a desolate rocky island, near India. Fortunately he is rescued by the flying island of Laputa

, a kingdom devoted to the arts of music

and mathematics

but unable to use them for practical ends. ("Laputa" is Spanish for "the whore;" Swift was attacking reason and the deism

movement in this book, the last one he wrote for the Travels.)

Laputa's method of throwing rocks at rebellious surface cities also seems the first time that aerial bombardment

was conceived as a method of warfare. While there, he tours the country as the guest of a low-ranking courtier and sees the ruin brought about by blind pursuit of science without practical results, in a satire on bureaucracy and the Royal Society

and its experiments. At The Grand Academy of Lagado great resources and manpower are employed on researching completely preposterous and unnecessary schemes such as extracting sunbeams from cucumbers, softening marble for use in pillows, learning how to mix paint by smell, and uncovering political conspiracies by examining the excrement of suspicious persons (see muckraking

).

Gulliver is then taken to Balnibarbi to await a trader who can take him on to Japan. While waiting for passage, Gulliver takes a short side-trip to the island of Glubbdubdrib

, where he visits a magician's dwelling and discusses history with the ghosts of historical figures, the most obvious restatement of the "ancients versus moderns" theme in the book. In Luggnagg he encounters the struldbrug

s, unfortunates who are immortal, but not forever young, but rather forever old, complete with the infirmities of old age and considered legally dead at the age of eighty. After reaching Japan, Gulliver asks the Emperor "to excuse my performing the ceremony imposed upon my countrymen of trampling upon the crucifix

", which the Emperor grants. Gulliver returns home, determined to stay there for the rest of his days.

Despite his earlier intention of remaining at home, Gulliver returns to the sea as the captain of a merchantman as he is bored with his employment as a surgeon. On this voyage he is forced to find new additions to his crew who he believes to have turned the rest of the crew against him. His crew then mutiny, and after keeping him contained for some time resolve to leave him on the first piece of land they come across and continue as pirates. He is abandoned in a landing boat and comes first upon a race of (apparently) hideous deformed and savage humanoid creatures to which he conceives a violent antipathy. Shortly thereafter he meets a horse and comes to understand that they call themselves Houyhnhms (which in their language means "the perfection of nature"), and that they are the rulers, while the deformed creatures called Yahoos are human beings in their base form.

Gulliver becomes a member of the horse's household, and comes to both admire and emulate the Houyhnhnms and their lifestyle, rejecting his fellow humans as merely Yahoos endowed with some semblance of reason which they only use to exacerbate and add to the vices Nature gave them. However, an Assembly of the Houyhnhnms rules that Gulliver, a Yahoo with some semblance of reason, is a danger to their civilization, and expels him.

He is then rescued, against his will, by a Portuguese ship, and is surprised to see that Captain Pedro de Mendez, a Yahoo, is a wise, courteous and generous person. He returns to his home in England, but he is unable to reconcile himself to living among Yahoos and becomes a recluse, remaining in his house, largely avoiding his family and his wife, and spending several hours a day speaking with the horses in his stables.

This book uses coarse metaphors to describe human depravity, and the Houyhnhms are symbolized as not only perfected nature but also the emotional barrenness which Swift maintained that devotion to reason brought.

and others formed the Scriblerus Club

, with the aim of satirising then-popular literary genres. Swift, runs the theory, was charged with writing the memoirs of the club's imaginary author, Martinus Scriblerus. It is known from Swift's correspondence that the composition proper began in 1720 with the mirror-themed parts I and II written first, Part IV next in 1723 and Part III written in 1724, but amendments were made even while Swift was writing Drapier's Letters. By August 1725 the book was completed, and as Gulliver's Travels was a transparently anti-Whig

satire it is likely that Swift had the manuscript copied so his handwriting could not be used as evidence if a prosecution should arise (as had happened in the case of some of his Irish pamphlet

s). In March 1726 Swift travelled to London to have his work published; the manuscript was secretly delivered to the publisher Benjamin Motte

, who used five printing houses to speed production and avoid piracy. Motte, recognising a bestseller but fearing prosecution, simply cut or altered the worst offending passages (such as the descriptions of the court contests in Lilliput or the rebellion of Lindalino

), added some material in defence of Queen Anne to book II, and published it anyway. The first edition was released in two volumes on 26 October 1726, priced 8s. 6d. The book was an instant sensation and sold out its first run in less than a week.

Motte published Gulliver's Travels anonymously and, as was often the way with fashionable works, several follow-ups (Memoirs of the Court of Lilliput), parodies (Two Lilliputian Odes, The first on the Famous Engine With Which Captain Gulliver extinguish'd the Palace Fire...) and "keys" (Gulliver Decipher'd and Lemuel Gulliver's Travels into Several Remote Regions of the World Compendiously Methodiz'd, the second by Edmund Curll

who had similarly written a "key" to Swift's Tale of a Tub in 1705) were produced over the next few years. These were mostly printed anonymously (or occasionally pseudonymously) and were quickly forgotten. Swift had nothing to do with any of these and specifically disavowed them in Faulkner's edition of 1735. However, Swift's friend Alexander Pope

wrote a set of five Verses on Gulliver's Travels which Swift liked so much that he added them to the second edition of the book, though they are not nowadays generally included.

, printed a complete set of Swift's works to date, Volume III of which was Gulliver's Travels. As revealed in Faulkner's "Advertisement to the Reader", Faulkner had access to an annotated copy of Motte's work by "a friend of the author" (generally believed to be Swift's friend Charles Ford) which reproduced most of the manuscript free of Motte's amendments, the original manuscript having been destroyed. It is also believed that Swift at least reviewed proofs of Faulkner's edition before printing but this cannot be proven. Generally, this is regarded as the editio princeps

of Gulliver's Travels with one small exception, discussed below.

This edition had an added piece by Swift, A letter from Capt. Gulliver to his Cousin Sympson which complained of Motte's alterations to the original text, saying he had so much altered it that "I do hardly know mine own work" and repudiating all of Motte's changes as well as all the keys, libels, parodies, second parts and continuations that had appeared in the intervening years. This letter now forms part of many standard texts.

's poor-quality copper currency. Faulkner had omitted this passage, either because of political sensitivities raised by being an Irish publisher printing an anti-British satire or possibly because the text he worked from did not include the passage. In 1899 the passage was included in a new edition of the Collected Works. Modern editions derive from the Faulkner edition with the inclusion of this 1899 addendum.

Isaac Asimov

notes in The Annotated Gulliver that Lindalino is composed of double lins; hence, Dublin.

to a children's story, from proto-Science Fiction

to a forerunner of the modern novel

.

Published seven years after Daniel Defoe

's wildly successful Robinson Crusoe

, Gulliver's Travels may be read as a systematic rebuttal of Defoe's optimistic account of human capability. In The Unthinkable Swift: The Spontaneous Philosophy of a Church of England Man Warren Montag

argues that Swift was concerned to refute the notion that the individual precedes society, as Defoe's novel seems to suggest. Swift regarded such thought as a dangerous endorsement of Thomas Hobbes

' radical political philosophy and for this reason Gulliver repeatedly encounters established societies rather than desolate islands. The captain who invites Gulliver to serve as a surgeon aboard his ship on the disastrous third voyage is named Robinson.

Possibly one of the reasons for the book's classic status is that it can be seen as many things to many different people. Broadly, the book has three themes:

In terms of storytelling and construction the parts follow a pattern:

Of equal interest is the character of Gulliver himself — he progresses from a cheery optimist at the start of the first part to the pompous misanthrope of the book's conclusion and we may well have to filter our understanding of the work if we are to believe the final misanthrope wrote the whole work. In this sense Gulliver's Travels is a very modern and complex novel. There are subtle shifts throughout the book, such as when Gulliver begins to see all humans, not just those in Houyhnhnm-land, as Yahoos.

Despite the depth and subtlety of the book, it is often classified as a children's story because of the popularity of the Lilliput section (frequently bowdler

ised) as a book for children. It is still possible to buy books entitled Gulliver's Travels which contain only parts of the Lilliput voyage.

published in occasional issues of The Gentleman's Magazine

semi-fictionalized accounts of contemporary debates in the two Houses of Parliament

under the title of Debates in the Senate of Lilliput. The names of the speakers in the debates, other individuals mentioned, politicians and monarchs present and past, and most other countries and cities of Europe ("Degulia") and America ("Columbia") were thinly disguised under a variety of Swiftian pseudonyms. The disguised names, and the pretence that the accounts were really translations of speeches by Lilliputian politicians, were a reaction to a Parliamentary act forbidding the publication of accounts of its debates. Cave employed several writers on this series: William Guthrie

(June 1738-November 1740), Samuel Johnson

(November 1740-February 1743), and John Hawkesworth (February 1743-December 1746).

The popularity of Gulliver is such that the term "Lilliputian" has entered many languages as an adjective meaning "small and delicate". There is even a brand of cigar

called Lilliput which is small. In addition to this there are a series of collectible model-houses known as "Lilliput Lane". The smallest light bulb fitting (5mm diameter) in the Edison screw

series is called the "Lilliput Edison screw". In Dutch, the word "Lilliputter" is used for adults shorter than 1.30 meters. Conversely, "Brobdingnagian" appears in the Oxford English Dictionary

as a synonym for "very large" or "gigantic".

In like vein, the term "yahoo" is often encountered as a synonym

for "ruffian" or "thug".

In the discipline of computer architecture

, the terms big-endian and little-endian are used to describe two possible ways of laying out bytes in memory; see Endianness

. The terms derive from one of the satirical conflicts in the book, in which two religious sects of Lilliputians are divided between those who prefer cracking open their soft-boiled eggs from the little end, and those who prefer the big end.

Anglo-Irish

Anglo-Irish was a term used primarily in the 19th and early 20th centuries to identify a privileged social class in Ireland, whose members were the descendants and successors of the Protestant Ascendancy, mostly belonging to the Church of Ireland, which was the established church of Ireland until...

writer and clergyman Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift was an Irish satirist, essayist, political pamphleteer , poet and cleric who became Dean of St...

(also known as Dean Swift) that is both a satire

Satire

Satire is primarily a literary genre or form, although in practice it can also be found in the graphic and performing arts. In satire, vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, ideally with the intent of shaming individuals, and society itself, into improvement...

on human nature and a parody

Parody

A parody , in current usage, is an imitative work created to mock, comment on, or trivialise an original work, its subject, author, style, or some other target, by means of humorous, satiric or ironic imitation...

of the "travellers' tales" literary sub-genre. It is Swift's best known full-length work, and a classic of English literature

English literature

English literature is the literature written in the English language, including literature composed in English by writers not necessarily from England; for example, Robert Burns was Scottish, James Joyce was Irish, Joseph Conrad was Polish, Dylan Thomas was Welsh, Edgar Allan Poe was American, J....

.

The book became popular as soon as it was published (John Gay

John Gay

John Gay was an English poet and dramatist and member of the Scriblerus Club. He is best remembered for The Beggar's Opera , set to music by Johann Christoph Pepusch...

said in a 1726 letter to Swift that "it is universally read, from the cabinet council to the nursery"); since then, it has never been out of print.

Part I: A Voyage to Lilliput and Blefuscu

The book begins with a very short preamble in which Lemuel Gulliver

Lemuel Gulliver

Lemuel Gulliver is the protagonist and narrator of Gulliver's Travels, a novel written by Jonathan Swift, first published in 1726.-In Gulliver's Travels:...

, in the style of books of the time, gives a brief outline of his life and history prior to his voyages. He enjoys travelling, although it is that love of travel that is his downfall.

During his first voyage, Gulliver is washed ashore after a shipwreck and finds himself a prisoner of a race of tiny people, less than 6 inches high, who are inhabitants of the island country of Lilliput. After giving assurances of his good behaviour, he is given a residence in Lilliput and becomes a favourite of the court. From there, the book follows Gulliver's observations on the Court of Lilliput. He is also given the permission to roam around the city on a condition he not harm their subjects. Gulliver assists the Lilliputians to subdue their neighbours, the Blefuscidians, by stealing their fleet. However, he refuses to reduce the island nation of Blefuscu to a province of Lilliput, displeasing the King and the court. Gulliver is charged with treason and sentenced to be blinded. With the assistance of a kind friend, Gulliver escapes to Blefuscu, where he spots and retrieves an abandoned boat and sails out to be rescued by a passing ship which safely takes him back home.

This book of the Travels is a topical political satire (see below).

Part II: A Voyage to Brobdingnag

When the sailing ship Adventure is steered off course by storms and forced to go in to land for want of fresh water, Gulliver is abandoned by his companions and found by a farmer who is 72 feet (21.9 m) tall (the scale of Lilliput is approximately 1:12; of Brobdingnag

Brobdingnag

Brobdingnag is a fictional land in Jonathan Swift's satirical novel Gulliver's Travels occupied by giants. Lemuel Gulliver visits the land after the ship on which he is travelling is blown off course and he is separated from a party exploring the unknown land.The adjective Brobdingnagian has come...

12:1, judging from Gulliver estimating a man's step being 10 yards (9.1 m)). He brings Gulliver home and his daughter cares for Gulliver. The farmer treats him as a curiosity and exhibits him for money. The word gets out and the Queen of Brobdingnag wants to see the show. She loves Gulliver and he is then bought by her and kept as a favourite at court.

Since Gulliver is too small to use their huge chairs, beds, knives and forks, the queen commissions a small house to be built for Gulliver so that he can be carried around in it. This is referred to as his "travelling box." In between small adventures such as fighting giant wasps and being carried to the roof by a monkey, he discusses the state of Europe with the King. The King is not happy with Gulliver's accounts of Europe, especially upon learning of the use of guns and cannons. On a trip to the seaside, his travelling box is seized by a giant eagle which drops Gulliver and his box right into the sea where he is picked up by some sailors, who return him to England.

This book compares the truly moral man to the representative man, the latter of whom is clearly shown to be the lesser of the two; Swift, being in Anglican holy orders, was likely to make such comparisons.

Part III: A Voyage to Laputa, Balnibarbi, Luggnagg, Glubbdubdrib, and Japan

5 August 1706 — 16 April 1710After Gulliver's ship is attacked by pirates, he is maroon

Marooning

Marooning is the intentional leaving of someone in a remote area, such as an uninhabited island. The word appears in writing in approximately 1709, and is derived from the term maroon, a word for a fugitive slave, which could be a corruption of Spanish cimarrón, meaning a household animal who has...

ed close to a desolate rocky island, near India. Fortunately he is rescued by the flying island of Laputa

Laputa

Laputa is a fictional place from the book Gulliver's Travels by Jonathan Swift.Laputa is a fictional flying island or rock, about 4.5 miles in diameter, with an adamantine base, which its inhabitants can maneuver in any direction using magnetic levitation...

, a kingdom devoted to the arts of music

Music

Music is an art form whose medium is sound and silence. Its common elements are pitch , rhythm , dynamics, and the sonic qualities of timbre and texture...

and mathematics

Mathematics

Mathematics is the study of quantity, space, structure, and change. Mathematicians seek out patterns and formulate new conjectures. Mathematicians resolve the truth or falsity of conjectures by mathematical proofs, which are arguments sufficient to convince other mathematicians of their validity...

but unable to use them for practical ends. ("Laputa" is Spanish for "the whore;" Swift was attacking reason and the deism

Deism

Deism in religious philosophy is the belief that reason and observation of the natural world, without the need for organized religion, can determine that the universe is the product of an all-powerful creator. According to deists, the creator does not intervene in human affairs or suspend the...

movement in this book, the last one he wrote for the Travels.)

Laputa's method of throwing rocks at rebellious surface cities also seems the first time that aerial bombardment

Airstrike

An air strike is an attack on a specific objective by military aircraft during an offensive mission. Air strikes are commonly delivered from aircraft such as fighters, bombers, ground attack aircraft, attack helicopters, and others...

was conceived as a method of warfare. While there, he tours the country as the guest of a low-ranking courtier and sees the ruin brought about by blind pursuit of science without practical results, in a satire on bureaucracy and the Royal Society

Royal Society

The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, known simply as the Royal Society, is a learned society for science, and is possibly the oldest such society in existence. Founded in November 1660, it was granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II as the "Royal Society of London"...

and its experiments. At The Grand Academy of Lagado great resources and manpower are employed on researching completely preposterous and unnecessary schemes such as extracting sunbeams from cucumbers, softening marble for use in pillows, learning how to mix paint by smell, and uncovering political conspiracies by examining the excrement of suspicious persons (see muckraking

Muckraker

The term muckraker is closely associated with reform-oriented journalists who wrote largely for popular magazines, continued a tradition of investigative journalism reporting, and emerged in the United States after 1900 and continued to be influential until World War I, when through a combination...

).

Gulliver is then taken to Balnibarbi to await a trader who can take him on to Japan. While waiting for passage, Gulliver takes a short side-trip to the island of Glubbdubdrib

Glubbdubdrib

Glubbdubdrib was an island of sorcerers and magicians, one of the imaginary countries visited by Lemuel Gulliver in the satire Gulliver's Travels by Anglo-Irish author Jonathan Swift....

, where he visits a magician's dwelling and discusses history with the ghosts of historical figures, the most obvious restatement of the "ancients versus moderns" theme in the book. In Luggnagg he encounters the struldbrug

Struldbrug

In Jonathan Swift's novel Gulliver's Travels, the name struldbrug is given to those humans in the nation of Luggnagg who are born seemingly normal, but are in fact immortal. However, although struldbrugs do not die, they do nonetheless continue aging...

s, unfortunates who are immortal, but not forever young, but rather forever old, complete with the infirmities of old age and considered legally dead at the age of eighty. After reaching Japan, Gulliver asks the Emperor "to excuse my performing the ceremony imposed upon my countrymen of trampling upon the crucifix

Fumie

A was a likeness of Jesus or Mary upon which the religious authorities of the Tokugawa shogunate of Japan required suspected Christians to step in order to prove that they were not members of that outlawed religion. The use of fumi-e began with the persecution of Christians in Nagasaki in 1629...

", which the Emperor grants. Gulliver returns home, determined to stay there for the rest of his days.

Part IV: A Voyage to the Country of the Houyhnhnms

7 September 1710 – 2 July 1715Despite his earlier intention of remaining at home, Gulliver returns to the sea as the captain of a merchantman as he is bored with his employment as a surgeon. On this voyage he is forced to find new additions to his crew who he believes to have turned the rest of the crew against him. His crew then mutiny, and after keeping him contained for some time resolve to leave him on the first piece of land they come across and continue as pirates. He is abandoned in a landing boat and comes first upon a race of (apparently) hideous deformed and savage humanoid creatures to which he conceives a violent antipathy. Shortly thereafter he meets a horse and comes to understand that they call themselves Houyhnhms (which in their language means "the perfection of nature"), and that they are the rulers, while the deformed creatures called Yahoos are human beings in their base form.

Gulliver becomes a member of the horse's household, and comes to both admire and emulate the Houyhnhnms and their lifestyle, rejecting his fellow humans as merely Yahoos endowed with some semblance of reason which they only use to exacerbate and add to the vices Nature gave them. However, an Assembly of the Houyhnhnms rules that Gulliver, a Yahoo with some semblance of reason, is a danger to their civilization, and expels him.

He is then rescued, against his will, by a Portuguese ship, and is surprised to see that Captain Pedro de Mendez, a Yahoo, is a wise, courteous and generous person. He returns to his home in England, but he is unable to reconcile himself to living among Yahoos and becomes a recluse, remaining in his house, largely avoiding his family and his wife, and spending several hours a day speaking with the horses in his stables.

This book uses coarse metaphors to describe human depravity, and the Houyhnhms are symbolized as not only perfected nature but also the emotional barrenness which Swift maintained that devotion to reason brought.

Composition and history

It is uncertain exactly when Swift started writing Gulliver's Travels, but some sources suggest as early as 1713 when Swift, Gay, Pope, ArbuthnotJohn Arbuthnot

John Arbuthnot, often known simply as Dr. Arbuthnot, , was a physician, satirist and polymath in London...

and others formed the Scriblerus Club

Scriblerus Club

The Scriblerus Club was an informal group of friends that included Jonathan Swift, Alexander Pope, John Gay, John Arbuthnot, Henry St. John and Thomas Parnell. The group was founded in 1712 and lasted until the death of the founders, starting in 1732 and ending in 1745, with Pope and Swift being...

, with the aim of satirising then-popular literary genres. Swift, runs the theory, was charged with writing the memoirs of the club's imaginary author, Martinus Scriblerus. It is known from Swift's correspondence that the composition proper began in 1720 with the mirror-themed parts I and II written first, Part IV next in 1723 and Part III written in 1724, but amendments were made even while Swift was writing Drapier's Letters. By August 1725 the book was completed, and as Gulliver's Travels was a transparently anti-Whig

British Whig Party

The Whigs were a party in the Parliament of England, Parliament of Great Britain, and Parliament of the United Kingdom, who contested power with the rival Tories from the 1680s to the 1850s. The Whigs' origin lay in constitutional monarchism and opposition to absolute rule...

satire it is likely that Swift had the manuscript copied so his handwriting could not be used as evidence if a prosecution should arise (as had happened in the case of some of his Irish pamphlet

Pamphlet

A pamphlet is an unbound booklet . It may consist of a single sheet of paper that is printed on both sides and folded in half, in thirds, or in fourths , or it may consist of a few pages that are folded in half and saddle stapled at the crease to make a simple book...

s). In March 1726 Swift travelled to London to have his work published; the manuscript was secretly delivered to the publisher Benjamin Motte

Benjamin Motte

Benjamin Motte was a London publisher and son of Benjamin Motte, Sr. Motte published many works and is well known for his publishing of Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels.-Background:...

, who used five printing houses to speed production and avoid piracy. Motte, recognising a bestseller but fearing prosecution, simply cut or altered the worst offending passages (such as the descriptions of the court contests in Lilliput or the rebellion of Lindalino

Lindalino

Lindalino is a fictional city from the book Gulliver's Travels by Jonathan Swift. Lindalino successfully revolted against the flying island of Laputa. The name Lindalino is a play on words of Dublin ....

), added some material in defence of Queen Anne to book II, and published it anyway. The first edition was released in two volumes on 26 October 1726, priced 8s. 6d. The book was an instant sensation and sold out its first run in less than a week.

Motte published Gulliver's Travels anonymously and, as was often the way with fashionable works, several follow-ups (Memoirs of the Court of Lilliput), parodies (Two Lilliputian Odes, The first on the Famous Engine With Which Captain Gulliver extinguish'd the Palace Fire...) and "keys" (Gulliver Decipher'd and Lemuel Gulliver's Travels into Several Remote Regions of the World Compendiously Methodiz'd, the second by Edmund Curll

Edmund Curll

Edmund Curll was an English bookseller and publisher. His name has become synonymous, through the attacks on him by Alexander Pope, with unscrupulous publication and publicity. Curll rose from poverty to wealth through his publishing, and he did this by approaching book printing in a mercenary...

who had similarly written a "key" to Swift's Tale of a Tub in 1705) were produced over the next few years. These were mostly printed anonymously (or occasionally pseudonymously) and were quickly forgotten. Swift had nothing to do with any of these and specifically disavowed them in Faulkner's edition of 1735. However, Swift's friend Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope was an 18th-century English poet, best known for his satirical verse and for his translation of Homer. He is the third-most frequently quoted writer in The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations, after Shakespeare and Tennyson...

wrote a set of five Verses on Gulliver's Travels which Swift liked so much that he added them to the second edition of the book, though they are not nowadays generally included.

Faulkner's 1735 edition

In 1735 an Irish publisher, George FaulknerGeorge Faulkner

George Faulkner was one of the most important Irish printers and booksellers. He forged a publishing relationship with Jonathan Swift and parlayed that fame into an extensive trade...

, printed a complete set of Swift's works to date, Volume III of which was Gulliver's Travels. As revealed in Faulkner's "Advertisement to the Reader", Faulkner had access to an annotated copy of Motte's work by "a friend of the author" (generally believed to be Swift's friend Charles Ford) which reproduced most of the manuscript free of Motte's amendments, the original manuscript having been destroyed. It is also believed that Swift at least reviewed proofs of Faulkner's edition before printing but this cannot be proven. Generally, this is regarded as the editio princeps

Editio princeps

In classical scholarship, editio princeps is a term of art. It means, roughly, the first printed edition of a work that previously had existed only in manuscripts, which could be circulated only after being copied by hand....

of Gulliver's Travels with one small exception, discussed below.

This edition had an added piece by Swift, A letter from Capt. Gulliver to his Cousin Sympson which complained of Motte's alterations to the original text, saying he had so much altered it that "I do hardly know mine own work" and repudiating all of Motte's changes as well as all the keys, libels, parodies, second parts and continuations that had appeared in the intervening years. This letter now forms part of many standard texts.

Lindalino

The short (five paragraph) episode in Part III, telling of the rebellion of the surface city of Lindalino against the flying island of Laputa, was an obvious allegory to the affair of Drapier's Letters of which Swift was proud. Lindalino represented Dublin and the impositions of Laputa represented the British imposition of William WoodWilliam Wood (Mintmaster)

William Wood was a hardware manufacturer and mintmaster, noted for receiving a contract to strike an issue of Irish coinage from 1722 to 1724. He also struck the 'Rosa Americana' coins of British America during the same period....

's poor-quality copper currency. Faulkner had omitted this passage, either because of political sensitivities raised by being an Irish publisher printing an anti-British satire or possibly because the text he worked from did not include the passage. In 1899 the passage was included in a new edition of the Collected Works. Modern editions derive from the Faulkner edition with the inclusion of this 1899 addendum.

Isaac Asimov

Isaac Asimov

Isaac Asimov was an American author and professor of biochemistry at Boston University, best known for his works of science fiction and for his popular science books. Asimov was one of the most prolific writers of all time, having written or edited more than 500 books and an estimated 90,000...

notes in The Annotated Gulliver that Lindalino is composed of double lins; hence, Dublin.

Major themes

Gulliver's Travels has been the recipient of several designations: from Menippean satireMenippean satire

The genre of Menippean satire is a form of satire, usually in prose, which has a length and structure similar to a novel and is characterized by attacking mental attitudes instead of specific individuals...

to a children's story, from proto-Science Fiction

Science fiction

Science fiction is a genre of fiction dealing with imaginary but more or less plausible content such as future settings, futuristic science and technology, space travel, aliens, and paranormal abilities...

to a forerunner of the modern novel

Novel

A novel is a book of long narrative in literary prose. The genre has historical roots both in the fields of the medieval and early modern romance and in the tradition of the novella. The latter supplied the present generic term in the late 18th century....

.

Published seven years after Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe , born Daniel Foe, was an English trader, writer, journalist, and pamphleteer, who gained fame for his novel Robinson Crusoe. Defoe is notable for being one of the earliest proponents of the novel, as he helped to popularise the form in Britain and along with others such as Richardson,...

's wildly successful Robinson Crusoe

Robinson Crusoe

Robinson Crusoe is a novel by Daniel Defoe that was first published in 1719. Epistolary, confessional, and didactic in form, the book is a fictional autobiography of the title character—a castaway who spends 28 years on a remote tropical island near Trinidad, encountering cannibals, captives, and...

, Gulliver's Travels may be read as a systematic rebuttal of Defoe's optimistic account of human capability. In The Unthinkable Swift: The Spontaneous Philosophy of a Church of England Man Warren Montag

Warren Montag

Warren Montag is a professor of English and Comparative Literature at Occidental College in Los Angeles, California. He is known primarily for his work on twentieth century French theory, especially Althusser and his circle, as well as his studies of the philosopher Spinoza.-Overview:Montag's...

argues that Swift was concerned to refute the notion that the individual precedes society, as Defoe's novel seems to suggest. Swift regarded such thought as a dangerous endorsement of Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes of Malmesbury , in some older texts Thomas Hobbs of Malmsbury, was an English philosopher, best known today for his work on political philosophy...

' radical political philosophy and for this reason Gulliver repeatedly encounters established societies rather than desolate islands. The captain who invites Gulliver to serve as a surgeon aboard his ship on the disastrous third voyage is named Robinson.

Possibly one of the reasons for the book's classic status is that it can be seen as many things to many different people. Broadly, the book has three themes:

- a satirical view of the state of European government, and of petty differences between religions.

- an inquiry into whether men are inherently corrupt or whether they become corrupted.

- a restatement of the older "ancients versus moderns" controversy previously addressed by Swift in The Battle of the BooksThe Battle of the BooksThe Battle of the Books is the name of a short satire written by Jonathan Swift and published as part of the prolegomena to his A Tale of a Tub in 1704. It depicts a literal battle between books in the King's Library , as ideas and authors struggle for supremacy...

.

In terms of storytelling and construction the parts follow a pattern:

- The causes of Gulliver's misadventures become more malignant as time goes on - he is first shipwrecked, then abandoned, then attacked by strangers, then attacked by his own crew.

- Gulliver's attitude hardens as the book progresses — he is genuinely surprised by the viciousness and politicking of the Lilliputians but finds the behaviour of the Yahoos in the fourth part reflective of the behaviour of people.

- Each part is the reverse of the preceding part — Gulliver is big/small/wise/ignorant, the countries are complex/simple/scientific/natural, forms of government are worse/better/worse/better than England's.

- Gulliver's view between parts contrasts with its other coinciding part—Gulliver sees the tiny Lilliputians as being vicious and unscrupulous, and then the king of Brobdingnag sees Europe in exactly the same light. Gulliver sees the Laputians as unreasonable, and Gulliver's Houyhnhnm master sees humanity as equally so.

- No form of government is ideal—the simplistic Brobdingnagians enjoy public executions and have streets infested with beggars, the honest and upright Houyhnhnms who have no word for lying are happy to suppress the true nature of Gulliver as a Yahoo and are equally unconcerned about his reaction to being expelled.

- Specific individuals may be good even where the race is bad—Gulliver finds a friend in each of his travels and, despite Gulliver's rejection and horror toward all Yahoos, is treated very well by the Portuguese captain, Dom Pedro, who returns him to England at the novel's end.

Of equal interest is the character of Gulliver himself — he progresses from a cheery optimist at the start of the first part to the pompous misanthrope of the book's conclusion and we may well have to filter our understanding of the work if we are to believe the final misanthrope wrote the whole work. In this sense Gulliver's Travels is a very modern and complex novel. There are subtle shifts throughout the book, such as when Gulliver begins to see all humans, not just those in Houyhnhnm-land, as Yahoos.

Despite the depth and subtlety of the book, it is often classified as a children's story because of the popularity of the Lilliput section (frequently bowdler

Thomas Bowdler

Thomas Bowdler was an English physician who published an expurgated edition of William Shakespeare's work, edited by his sister Harriet, intended to be more appropriate for 19th century women and children than the original....

ised) as a book for children. It is still possible to buy books entitled Gulliver's Travels which contain only parts of the Lilliput voyage.

Cultural influences

From 1738 to 1746, Edward CaveEdward Cave

Edward Cave was an English printer, editor and publisher. In The Gentleman's Magazine he created the first general-interest "magazine" in the modern sense....

published in occasional issues of The Gentleman's Magazine

The Gentleman's Magazine

The Gentleman's Magazine was founded in London, England, by Edward Cave in January 1731. It ran uninterrupted for almost 200 years, until 1922. It was the first to use the term "magazine" for a periodical...

semi-fictionalized accounts of contemporary debates in the two Houses of Parliament

Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body in the United Kingdom, British Crown dependencies and British overseas territories, located in London...

under the title of Debates in the Senate of Lilliput. The names of the speakers in the debates, other individuals mentioned, politicians and monarchs present and past, and most other countries and cities of Europe ("Degulia") and America ("Columbia") were thinly disguised under a variety of Swiftian pseudonyms. The disguised names, and the pretence that the accounts were really translations of speeches by Lilliputian politicians, were a reaction to a Parliamentary act forbidding the publication of accounts of its debates. Cave employed several writers on this series: William Guthrie

William Guthrie (historian)

William Guthrie was a Scottish writer and journalist, now remembered as a historian.-Life:The son of an Episcopalian clergyman, he was born at Brechin, Forfarshire, in 1708...

(June 1738-November 1740), Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson , often referred to as Dr. Johnson, was an English author who made lasting contributions to English literature as a poet, essayist, moralist, literary critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer...

(November 1740-February 1743), and John Hawkesworth (February 1743-December 1746).

The popularity of Gulliver is such that the term "Lilliputian" has entered many languages as an adjective meaning "small and delicate". There is even a brand of cigar

Cigar

A cigar is a tightly-rolled bundle of dried and fermented tobacco that is ignited so that its smoke may be drawn into the mouth. Cigar tobacco is grown in significant quantities in Brazil, Cameroon, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Honduras, Indonesia, Mexico, Nicaragua, Philippines, and the Eastern...

called Lilliput which is small. In addition to this there are a series of collectible model-houses known as "Lilliput Lane". The smallest light bulb fitting (5mm diameter) in the Edison screw

Edison screw

The Edison screw fitting is a system of connectors used for light bulbs, developed by Thomas Edison and licensed starting in 1909 under the Mazda trademark. Most have a right-hand threading, so that it goes in when turned clockwise and comes out when turned counterclockwise, like a hardware screw...

series is called the "Lilliput Edison screw". In Dutch, the word "Lilliputter" is used for adults shorter than 1.30 meters. Conversely, "Brobdingnagian" appears in the Oxford English Dictionary

Oxford English Dictionary

The Oxford English Dictionary , published by the Oxford University Press, is the self-styled premier dictionary of the English language. Two fully bound print editions of the OED have been published under its current name, in 1928 and 1989. The first edition was published in twelve volumes , and...

as a synonym for "very large" or "gigantic".

In like vein, the term "yahoo" is often encountered as a synonym

Synonym

Synonyms are different words with almost identical or similar meanings. Words that are synonyms are said to be synonymous, and the state of being a synonym is called synonymy. The word comes from Ancient Greek syn and onoma . The words car and automobile are synonyms...

for "ruffian" or "thug".

In the discipline of computer architecture

Computer architecture

In computer science and engineering, computer architecture is the practical art of selecting and interconnecting hardware components to create computers that meet functional, performance and cost goals and the formal modelling of those systems....

, the terms big-endian and little-endian are used to describe two possible ways of laying out bytes in memory; see Endianness

Endianness

In computing, the term endian or endianness refers to the ordering of individually addressable sub-components within the representation of a larger data item as stored in external memory . Each sub-component in the representation has a unique degree of significance, like the place value of digits...

. The terms derive from one of the satirical conflicts in the book, in which two religious sects of Lilliputians are divided between those who prefer cracking open their soft-boiled eggs from the little end, and those who prefer the big end.

Sequels and imitations

- Many sequels followed the initial publishing of the Travels. The earliest of these was the anonymously authored Memoirs of the Court of Lilliput, published 1727, which expands the account of Gulliver's stays in Lilliput and Blefuscu by adding several gossipy anecdotes about scandalous episodes at the Lilliputian court.

- Abbé Pierre DesfontainesPierre DesfontainesThe Abbé Pierre François Guyot-Desfontaines was a French journalist, translator and popular historian....

, the first French translator of Swift's story, wrote a sequel, Le Nouveau Gulliver ou Voyages de Jean Gulliver, fils du capitaine Lemuel Gulliver (The New Gulliver, or the travels of John Gulliver, son of Captain Lemuel Gulliver), published in 1730. Gulliver's son has various fantastic, satirical adventures. - Soviet UkrainianUkrainiansUkrainians are an East Slavic ethnic group native to Ukraine, which is the sixth-largest nation in Europe. The Constitution of Ukraine applies the term 'Ukrainians' to all its citizens...

science fiction writer Vladimir Savchenko published Gulliver's Fifth Travel - The Travel of Lemuel Gulliver, First a Surgeon, and Then a Captain of Several Ships to the Land of Tikitaks - a sequel to the original series in which Gulliver's role as a surgeon is more apparent. Tikitaks are people who inject the juice of a unique fruit to make their skin transparent, as they consider people with regular opaque skin secretive and ugly. - American physician John Paul Brady published in 1987 A Voyage to Inishneefa: A First-hand Account of the Fifth Voyage of Lemuel Gulliver (Santa Barbara: John Daniel), a parody of Irish history in Swift's manner.

Allusions

- Philip K. DickPhilip K. DickPhilip Kindred Dick was an American novelist, short story writer and essayist whose published work is almost entirely in the science fiction genre. Dick explored sociological, political and metaphysical themes in novels dominated by monopolistic corporations, authoritarian governments and altered...

's short story "Prize Ship" (1954) loosely referred to Gulliver's Travels - In the 9th book of The Time Wars SeriesTimeWarsTimeWars is a series of twelve science fiction paperback books created and written by author Simon Hawke beginning in 1984. The story involves the adventures of an organization tasked with protecting history from being changed by time travelers...

, Simon Hawke'sSimon HawkeSimon Hawke is an American author of mainly science fiction and fantasy novels. He was born Nicholas Valentin Yermakov, but began writing as Simon Hawke in 1984 and later changed his legal name to Hawke. He has also written near future adventure novels under the penname "J. D...

The Lilliput Legion, the protagonists meet Lemuel Gulliver and battle the titular army. - The BBC Radio 4BBC Radio 4BBC Radio 4 is a British domestic radio station, operated and owned by the BBC, that broadcasts a wide variety of spoken-word programmes, including news, drama, comedy, science and history. It replaced the BBC Home Service in 1967. The station controller is currently Gwyneth Williams, and the...

comedy series Brian Gulliver's TravelsBrian Gulliver's TravelsBrian Gulliver's Travels is a satirical sitcom on BBC Radio 4 created and written by Bill Dare, first broadcast on 21st February, 2011. The series is a modern pastiche of the Jonathan Swift novel Gulliver's Travels. The series revolves around the character Brian Gulliver, played by Neil Pearson...

by Bill DareBill DareBill Dare is an English producer and devisor of radio and television comedy programmes.The son of the actor and broadcaster Peter Jones, he is a graduate of the University of Manchester who subsequently became an actor, director and writer...

is a satirical comedy about a travel documentaryTravel documentaryA travel documentary is a documentary film or television program that describes travel in general or tourist attractions in a non-commercial way....

presenter, Brian Gulliver (played by Neil PearsonNeil PearsonNeil Joshua Pearson is a British actor best known for his work on television.-Biography:Pearson grew up in Battersea, London, the son of a panel beater, who left home when he was five, and a legal secretary, and was educated at Woolverstone Hall School, Suffolk, a boarding school, where he first...

), who talks about his adventures in the undiscovered continent of Clafenia. Gulliver's Travels was the only book Dare read while he was at the university.

Adaptations

Music

- The band Soufferance based and theme their 2010 album on the book, as "Travels Into Several Remote Nations of the Mind".

Film, television and radio

Gulliver's Travels has been adapted several times for film, television and radio.- Gulliver's TravelsGulliver's Travels (1939 film)Gulliver's Travels is a 1939 American cel-animated Technicolor feature film, directed by Dave Fleischer and produced by Max Fleischer for Fleischer Studios. The film was released on Friday, December 22, 1939 by Paramount Pictures, who had the feature produced as an answer to the success of Walt...

(1939): Max FleischerMax FleischerMax Fleischer was an American animator. He was a pioneer in the development of the animated cartoon and served as the head of Fleischer Studios...

's animated classic of Gulliver's adventures in Lilliput. - Case for a Rookie HangmanCase for a Rookie HangmanCase for a Rookie Hangman is a Czech drama film directed by Pavel Juráček. It was released in 1970. The movie belongs to the Czech New Wave....

(1970): A satirical movie by the Czech Pavel JuráčekPavel JurácekPavel Juráček was a Czech screenwriter and film director. Although not as famous as Miloš Forman or Jiří Menzel, he was an exponent of the Czech New Wave as well...

, based upon the third book, depicting indirectly the Communist CzechoslovakiaCzechoslovakiaCzechoslovakia or Czecho-Slovakia was a sovereign state in Central Europe which existed from October 1918, when it declared its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992...

, shelved soon after its release. - Gulliver's Travels (TV miniseries)Gulliver's Travels (TV miniseries)Gulliver's Travels is a U.S. TV miniseries based on Jonathan Swift's novel of the same name, produced by Jim Henson Productions and Hallmark Entertainment. This miniseries is notable for being one of the very few adaptations of Swift's novel to feature all four voyages. The miniseries aired in the...

(1996) Live-action, 2 part, TV series with special effects starring Ted DansonTed DansonEdward Bridge “Ted” Danson III is an American actor best known for his role as central character Sam Malone in the sitcom Cheers, and his role as Dr. John Becker on the series Becker. He also plays a recurring role on Larry David's HBO sitcom Curb Your Enthusiasm and starred alongside Glenn Close...

and Mary SteenburgenMary SteenburgenMary Nell Steenburgen is an American actress. She is best known for playing the role of Lynda Dummar in Jonathan Demme's Melvin and Howard, which earned her an Academy Award and a Golden Globe.-Early life:...

also featuring a variety of film stars. - Gulliver's TravelsGulliver's Travels (2010 film)Gulliver's Travels is a 2010 fantasy comedy film directed by Rob Letterman and very loosely based on Part One of the 18th-century novel of the same name by Jonathan Swift, though the film takes place in modern day...

(2010): Live-action version of Gulliver's adventures in Lilliput, starring Jack BlackJack BlackJack Black , is an American actor and musician, notably of Tenacious D.Jack Black may also refer to:* Jack Black , late 19th - early 20th Century author and hobo* Jack Black , drummer for 1970s UK punk band The Boys...

, also featuring Billy ConnollyBilly ConnollyWilliam "Billy" Connolly, Jr., CBE is a Scottish comedian, musician, presenter and actor. He is sometimes known, especially in his native Scotland, by the nickname The Big Yin...

, James CordenJames CordenJames Kimberley Corden is an English actor, television writer, producer and presenter. He is co-creator and star of BBC comedy shows Gavin & Stacey and Horne & Corden, and acted in the 2009 film Lesbian Vampire Killers....

, Amanda PeetAmanda PeetAmanda Peet is an American actress, who has appeared on film, stage, and television. After studying with Uta Hagen at Columbia University, Peet began her career in television commercials, and progressed to small roles on television, before making her film debut in 1995...

, Chris O'DowdChris O'DowdChris O'Dowd is an Irish comedian and actor. He is best known for playing Roy Trenneman in British sitcom The IT Crowd...

, Catherine TateCatherine TateCatherine Tate is an English actress, writer, and comedian. She has won numerous awards for her work on the sketch comedy series The Catherine Tate Show as well as being nominated for an International Emmy Award and four BAFTA Awards...

, Jason SegelJason SegelJason Jordan Segel is an American television and film actor, screenwriter, composer, puppeteer and musician, known for his work with producer Judd Apatow on the short-lived television series Freaks and Geeks and Undeclared, the films Forgetting Sarah Marshall, Knocked Up, I Love You, Man,...

, Emily BluntEmily BluntEmily Olivia Leah Blunt is an English actress best known for her roles in The Devil Wears Prada , The Young Victoria , and The Adjustment Bureau . She has been nominated for two Golden Globe Awards, two London Film Critics' Circle Awards, and one BAFTA Award...

and Olly Alexander.

See also

- Bigendian

- BrobdingnagBrobdingnagBrobdingnag is a fictional land in Jonathan Swift's satirical novel Gulliver's Travels occupied by giants. Lemuel Gulliver visits the land after the ship on which he is travelling is blown off course and he is separated from a party exploring the unknown land.The adjective Brobdingnagian has come...

- The EngineThe EngineThe Engine is a fictional device described in Gulliver's Travels by Jonathan Swift in 1726. It is possibly the earliest known reference to a device in any way resembling a modern computer. It is found at the Academy of Projectors in Lagado and is described thus by Swift:“.....

- GlubbdubdribGlubbdubdribGlubbdubdrib was an island of sorcerers and magicians, one of the imaginary countries visited by Lemuel Gulliver in the satire Gulliver's Travels by Anglo-Irish author Jonathan Swift....

- Lemuel GulliverLemuel GulliverLemuel Gulliver is the protagonist and narrator of Gulliver's Travels, a novel written by Jonathan Swift, first published in 1726.-In Gulliver's Travels:...

- HouyhnhnmHouyhnhnmHouyhnhnms are a race of intelligent horses described in the last part of Jonathan Swift's satirical Gulliver's Travels. The name is pronounced either or ....

- LagadoLagadoLagado is a fictional city from the book of Gulliver's Travels by Jonathan Swift.Lagado is the capital of the nation Balnibarbi, which is ruled by a tyrannical king from a flying island called Laputa. Lagado is on the ground below Laputa, and also has access to Laputa at any given time to proceed...

- LaputaLaputaLaputa is a fictional place from the book Gulliver's Travels by Jonathan Swift.Laputa is a fictional flying island or rock, about 4.5 miles in diameter, with an adamantine base, which its inhabitants can maneuver in any direction using magnetic levitation...

- Lilliput and BlefuscuLilliput and BlefuscuLilliput and Blefuscu are two fictional island nations that appear in the first part of the 1726 novel Gulliver's Travels by Jonathan Swift. The two islands are neighbors in the South Indian Ocean, separated by a channel eight hundred yards wide. Both are inhabited by tiny people who are about...

- LindalinoLindalinoLindalino is a fictional city from the book Gulliver's Travels by Jonathan Swift. Lindalino successfully revolted against the flying island of Laputa. The name Lindalino is a play on words of Dublin ....

- StruldbrugStruldbrugIn Jonathan Swift's novel Gulliver's Travels, the name struldbrug is given to those humans in the nation of Luggnagg who are born seemingly normal, but are in fact immortal. However, although struldbrugs do not die, they do nonetheless continue aging...

- Yahoo

Online Text

- Gulliver's Travels, full text and audio.

- RSS edition of the text

- Searchable version in multiple formats ( html, XML, opendocument ODF, pdf (landscape, portrait), plaintext, concordance ) SiSUSiSUSiSU , is a Unix command line-oriented framework for document structuring, publishing and search.-Usage:...