Harry Johnston

Encyclopedia

Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate mediæval ceremony for creating a knight, which involved bathing as one of its elements. The knights so created were known as Knights of the Bath...

(12 June 1858 - 31 August 1927), was a British

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

explorer, botanist, linguist and colonial administrator

Administrator of the Government

An Administrator in the constitutional practice of some countries in the Commonwealth is a person who fulfils a role similar to that of a Governor or a Governor-General...

, one of the key players in the "Scramble for Africa

Scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa, also known as the Race for Africa or Partition of Africa was a process of invasion, occupation, colonization and annexation of African territory by European powers during the New Imperialism period, between 1881 and World War I in 1914...

" that occurred at the end of the 19th century.

Early years

Born at Kennington ParkKennington Park

Kennington Park is in Kennington in London, England, and lies between Kennington Park Road and St Agnes Place. It was opened in 1854. Previously the site had been Kennington Common. This is where the Chartists gathered for their biggest 'monster rally' on 10 April 1848...

, south London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

, he attended Stockwell

Stockwell

Stockwell is a district in inner south west London, England, located in the London Borough of Lambeth.It is situated south south-east of Charing Cross. Brixton, Clapham, Vauxhall and Kennington all border Stockwell...

grammar school and then King's College London

King's College London

King's College London is a public research university located in London, United Kingdom and a constituent college of the federal University of London. King's has a claim to being the third oldest university in England, having been founded by King George IV and the Duke of Wellington in 1829, and...

, followed by four years studying painting

Painting

Painting is the practice of applying paint, pigment, color or other medium to a surface . The application of the medium is commonly applied to the base with a brush but other objects can be used. In art, the term painting describes both the act and the result of the action. However, painting is...

at the Royal Academy

Royal Academy

The Royal Academy of Arts is an art institution based in Burlington House on Piccadilly, London. The Royal Academy of Arts has a unique position in being an independent, privately funded institution led by eminent artists and architects whose purpose is to promote the creation, enjoyment and...

. In connection with his study he traveled to Europe

Europe

Europe is, by convention, one of the world's seven continents. Comprising the westernmost peninsula of Eurasia, Europe is generally 'divided' from Asia to its east by the watershed divides of the Ural and Caucasus Mountains, the Ural River, the Caspian and Black Seas, and the waterways connecting...

and North Africa

North Africa

North Africa or Northern Africa is the northernmost region of the African continent, linked by the Sahara to Sub-Saharan Africa. Geopolitically, the United Nations definition of Northern Africa includes eight countries or territories; Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco, South Sudan, Sudan, Tunisia, and...

, visiting the little-known (by Europeans) interior of Tunisia

Tunisia

Tunisia , officially the Tunisian RepublicThe long name of Tunisia in other languages used in the country is: , is the northernmost country in Africa. It is a Maghreb country and is bordered by Algeria to the west, Libya to the southeast, and the Mediterranean Sea to the north and east. Its area...

in 1879 and 1880.

Exploration in Africa

In 1882 he visited southern AngolaAngola

Angola, officially the Republic of Angola , is a country in south-central Africa bordered by Namibia on the south, the Democratic Republic of the Congo on the north, and Zambia on the east; its west coast is on the Atlantic Ocean with Luanda as its capital city...

with the Earl of Mayo

Earl of Mayo

Earl of the County of Mayo, usually known simply as Earl of Mayo, is a title in the Peerage of Ireland. It was created in 1785 for John Bourke, 1st Viscount Mayo, for many years First Commissioner of Revenue in Ireland...

, and in the following year met Henry Morton Stanley

Henry Morton Stanley

Sir Henry Morton Stanley, GCB, born John Rowlands , was a Welsh journalist and explorer famous for his exploration of Africa and his search for David Livingstone. Upon finding Livingstone, Stanley allegedly uttered the now-famous greeting, "Dr...

in the Congo

Congo River

The Congo River is a river in Africa, and is the deepest river in the world, with measured depths in excess of . It is the second largest river in the world by volume of water discharged, though it has only one-fifth the volume of the world's largest river, the Amazon...

, becoming one of the first Europeans after Stanley to see the river above the Stanley Pool

Pool Malebo

The Pool Malebo , is a lake-like widening in the lower reaches of the Congo River....

. His developing reputation led the Royal Geographical Society

Royal Geographical Society

The Royal Geographical Society is a British learned society founded in 1830 for the advancement of geographical sciences...

and the British Association

British Association for the Advancement of Science

frame|right|"The BA" logoThe British Association for the Advancement of Science or the British Science Association, formerly known as the BA, is a learned society with the object of promoting science, directing general attention to scientific matters, and facilitating interaction between...

to appoint him leader of an 1884 scientific expedition to Mount Kilimanjaro

Mount Kilimanjaro

Kilimanjaro, with its three volcanic cones, Kibo, Mawenzi, and Shira, is a dormant volcano in Kilimanjaro National Park, Tanzania and the highest mountain in Africa at above sea level .-Geology:...

. On this expedition he concluded treaties with local chiefs (which were then transferred to the British East Africa Company), in competition with German efforts to do likewise.

British colonial service and the Cape to Cairo vision

In October 1886 the British government appointed him vice-consul in CameroonCameroon

Cameroon, officially the Republic of Cameroon , is a country in west Central Africa. It is bordered by Nigeria to the west; Chad to the northeast; the Central African Republic to the east; and Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, and the Republic of the Congo to the south. Cameroon's coastline lies on the...

and the Niger River

Niger River

The Niger River is the principal river of western Africa, extending about . Its drainage basin is in area. Its source is in the Guinea Highlands in southeastern Guinea...

delta area, where a protectorate had been declared in 1885, and he became acting consul in 1887, deposing and banishing the local chief Jaja

Jaja

Jaja may refer to:*Jackson Avelino Coelho, Brazilian footballer nicknamed Jajá*Jaja Wachukwu, Nigerian politician and humanitarian*Jaja of Opobo, the first monarchy of Opobo*Laurent Jalabert, retired French professional cyclist nicknamed Jaja...

. On leave in England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

in 1888, he met with Lord Salisbury

Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury

Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury, KG, GCVO, PC , styled Lord Robert Cecil before 1865 and Viscount Cranborne from June 1865 until April 1868, was a British Conservative statesman and thrice Prime Minister, serving for a total of over 13 years...

and apparently helped formulate the Cape to Cairo plan to acquire a continuous band of territory down Africa, which he then leaked (with Salisbury's approval) to the Times

The Times

The Times is a British daily national newspaper, first published in London in 1785 under the title The Daily Universal Register . The Times and its sister paper The Sunday Times are published by Times Newspapers Limited, a subsidiary since 1981 of News International...

in an anonymous article "by an African Explorer".

Nyasaland (British Central Africa Protectorate)

In 1889 Johnston was sent to LisbonLisbon

Lisbon is the capital city and largest city of Portugal with a population of 545,245 within its administrative limits on a land area of . The urban area of Lisbon extends beyond the administrative city limits with a population of 3 million on an area of , making it the 9th most populous urban...

to negotiate the Portuguese and British spheres of influence

Sphere of influence

In the field of international relations, a sphere of influence is a spatial region or conceptual division over which a state or organization has significant cultural, economic, military or political influence....

in southeastern Africa, then went to Mozambique

Mozambique

Mozambique, officially the Republic of Mozambique , is a country in southeastern Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi and Zambia to the northwest, Zimbabwe to the west and Swaziland and South Africa to the southwest...

as consul. From there he went to Lake Nyasa to resolve the war between Arab

Arab

Arab people, also known as Arabs , are a panethnicity primarily living in the Arab world, which is located in Western Asia and North Africa. They are identified as such on one or more of genealogical, linguistic, or cultural grounds, with tribal affiliations, and intra-tribal relationships playing...

slave-traders and the African Lakes Trading Company. Alarm over the presence of the Portuguese Serpa Pinto triggered the Anglo-Portuguese Crisis, which ended with Johnston having Nyasaland (today's Malawi

Malawi

The Republic of Malawi is a landlocked country in southeast Africa that was formerly known as Nyasaland. It is bordered by Zambia to the northwest, Tanzania to the northeast, and Mozambique on the east, south and west. The country is separated from Tanzania and Mozambique by Lake Malawi. Its size...

) declared the British Central Africa Protectorate, and he was made its first commissioner in 1891.

Scramble for Katanga

In 1890 acting for Cecil Rhodes and the British South Africa Company (BSAC)British South Africa Company

The British South Africa Company was established by Cecil Rhodes through the amalgamation of the Central Search Association and the Exploring Company Ltd., receiving a royal charter in 1889...

, Johnston sent Alfred Sharpe

Alfred Sharpe

Sir Alfred Sharpe was a professional hunter who became a British colonial administrator and Commissioner of the British Central Africa Protectorate from 1896 until 1910...

(who would become his successor in Nyasaland) to obtain a treaty with Msiri, King of Garanganze

Yeke Kingdom

The Yeke Kingdom of the Garanganze people in Katanga, DR Congo was short-lived, existing from about 1856 to 1891 under one king, Msiri, but it became for a while the most powerful state in south-central Africa, controlling a territory of about half a million square kilometres...

in Katanga

Katanga Province

Katanga Province is one of the provinces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Between 1971 and 1997, its official name was Shaba Province. Under the new constitution, the province was to be replaced by four smaller provinces by February 2009; this did not actually take place.Katanga's regional...

. This territory was in the sphere of influence of Belgian King Leopold II's

Leopold II of Belgium

Leopold II was the second king of the Belgians. Born in Brussels the second son of Leopold I and Louise-Marie of Orléans, he succeeded his father to the throne on 17 December 1865 and remained king until his death.Leopold is chiefly remembered as the founder and sole owner of the Congo Free...

Congo Free State

Congo Free State

The Congo Free State was a large area in Central Africa which was privately controlled by Leopold II, King of the Belgians. Its origins lay in Leopold's attracting scientific, and humanitarian backing for a non-governmental organization, the Association internationale africaine...

, and though the Berlin Conference's Principle of Effectivity allowed such a move, it had the potential to precipitate an Anglo-Belgian crisis. Sharpe failed with Msiri, though he obtained treaties with Mwata Kazembe covering the eastern side of the Luapula River

Luapula River

The Luapula River is a section of Africa's second-longest river, the Congo. It is a transnational river forming for nearly all its length part of the border between Zambia and the DR Congo...

and Lake Mweru

Lake Mweru

Lake Mweru is a freshwater lake on the longest arm of Africa's second-longest river, the Congo. Located on the border between Zambia and Democratic Republic of the Congo, it makes up 110 km of the total length of the Congo, lying between its Luapula River and Luvua River segments.Mweru...

, and with other chiefs covering the southern end of Lake Tanganyika

Lake Tanganyika

Lake Tanganyika is an African Great Lake. It is estimated to be the second largest freshwater lake in the world by volume, and the second deepest, after Lake Baikal in Siberia; it is also the world's longest freshwater lake...

. In 1891 Leopold sent the Stairs Expedition to Katanga. Johnston dissuaded it from accessing Katanga through Nyasaland, but it went through German East Africa

German East Africa

German East Africa was a German colony in East Africa, which included what are now :Burundi, :Rwanda and Tanganyika . Its area was , nearly three times the size of Germany today....

instead, and took Katanga after killing Msiri.

North-Eastern Rhodesia and Nyasaland

Johnston realised the strategic importance of Lake Tanganyika to the British, especially since the territory between the lake and the coast had become German East AfricaGerman East Africa

German East Africa was a German colony in East Africa, which included what are now :Burundi, :Rwanda and Tanganyika . Its area was , nearly three times the size of Germany today....

forming a break of nearly 900 km in the chain of British colonies in the Cape to Cairo dream. However the north end of Lake Tanganyika was only 230 km from British-controlled Uganda

Uganda

Uganda , officially the Republic of Uganda, is a landlocked country in East Africa. Uganda is also known as the "Pearl of Africa". It is bordered on the east by Kenya, on the north by South Sudan, on the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, on the southwest by Rwanda, and on the south by...

, and so a British presence at the south end of the lake was a priority.

With Belgian, German and Portuguese frontiers to contend with, Johnston ensured that British bomas were established (in addition to those in Nyasaland) east of Luapula-Mweru at Chiengi

Chiengi

Chiengi or Chienge was a historic colonial boma of the British Empire in central Africa and today is a settlement in the Luapula Province of Zambia, and headquarters of Chiengi District...

and the Kalungwishi River

Kalungwishi River

The Kalungwishi River flows west in northern Zambia into Lake Mweru. It is known for its waterfalls, including the Lumangwe Falls, Kabweluma Falls, Kundabwiku Falls and Mumbuluma Falls....

, at the south end of Lake Tanganyika

Lake Tanganyika

Lake Tanganyika is an African Great Lake. It is estimated to be the second largest freshwater lake in the world by volume, and the second deepest, after Lake Baikal in Siberia; it is also the world's longest freshwater lake...

at Abercorn

Abercorn

Abercorn is a village and parish in West Lothian, Scotland. Close to the south coast of the Firth of Forth, the village is around west of South Queensferry.-History:...

, and at Fort Jameson between Mozambique

Mozambique

Mozambique, officially the Republic of Mozambique , is a country in southeastern Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi and Zambia to the northwest, Zimbabwe to the west and Swaziland and South Africa to the southwest...

and the Luangwa valley

Luangwa River

The Luangwa River is one of the major tributaries of the Zambezi River, and one of the four biggest rivers of Zambia. The river generally floods in the rainy season and then falls considerably in the dry season...

. At these bomas he helped set up and oversee the British South Africa Company's administration in the territory which became North-Eastern Rhodesia

North-Eastern Rhodesia

North-Eastern Rhodesia in south central Africa was formed by and administered by the British South Africa Company as the other half, with North-Western Rhodesia, of the huge territory lying mainly north of the Zambezi River into which it expanded its charter in 1891...

(the north-eastern half of today's Zambia

Zambia

Zambia , officially the Republic of Zambia, is a landlocked country in Southern Africa. The neighbouring countries are the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the north, Tanzania to the north-east, Malawi to the east, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Botswana and Namibia to the south, and Angola to the west....

). Although he missed out in Katanga, altogether he helped to consolidate an area of nearly half a million square kilometres - say nearly 200000 square miles (517,997.6 km²), or twice the area of the United Kingdom in 2009 - lying between the lower Luangwa River

Luangwa River

The Luangwa River is one of the major tributaries of the Zambezi River, and one of the four biggest rivers of Zambia. The river generally floods in the rainy season and then falls considerably in the dry season...

valley and lakes Nyasa, Tanganyika

Lake Tanganyika

Lake Tanganyika is an African Great Lake. It is estimated to be the second largest freshwater lake in the world by volume, and the second deepest, after Lake Baikal in Siberia; it is also the world's longest freshwater lake...

, and Mweru

Lake Mweru

Lake Mweru is a freshwater lake on the longest arm of Africa's second-longest river, the Congo. Located on the border between Zambia and Democratic Republic of the Congo, it makes up 110 km of the total length of the Congo, lying between its Luapula River and Luvua River segments.Mweru...

into the British Empire

British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom. It originated with the overseas colonies and trading posts established by England in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. At its height, it was the...

.

Later years

In 1896 in recognition of this achievement he was appointed Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath (KCB), but afflicted by tropical fevers, transferred to TunisTunis

Tunis is the capital of both the Tunisian Republic and the Tunis Governorate. It is Tunisia's largest city, with a population of 728,453 as of 2004; the greater metropolitan area holds some 2,412,500 inhabitants....

as consul-general. In the same year, he had married the Hon. Winifred Mary Irby, daughter of Florance George Henry Irby, fifth Baron Boston.

In 1899 Sir Harry was sent to Uganda

Uganda

Uganda , officially the Republic of Uganda, is a landlocked country in East Africa. Uganda is also known as the "Pearl of Africa". It is bordered on the east by Kenya, on the north by South Sudan, on the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, on the southwest by Rwanda, and on the south by...

as special commissioner to end an ongoing war. He improved the colonial administration, and in 1900 concluded the Buganda Agreement dividing the land between the UK and the chiefs.

In 1902 his wife gave birth prematurely to twin boys, but neither survived more than a few hours, and they had no more children. His sister, Mabel Johnston, married Arnold Dolmetsch

Arnold Dolmetsch

Arnold Dolmetsch , was a French-born musician and instrument maker who spent much of his working life in England and established an instrument-making workshop in Haslemere, Surrey...

, an instrument maker and member of the Bloomsbury

Bloomsbury

-Places:* Bloomsbury is an area in central London.* Bloomsbury , related local government unit* Bloomsbury, New Jersey, New Jersey, USA* Bloomsbury , listed on the NRHP in Maryland...

set, in 1903.

In 1903 and in 1906 he stood for parliament for the Liberal Party

Liberal Party (UK)

The Liberal Party was one of the two major political parties of the United Kingdom during the 19th and early 20th centuries. It was a third party of negligible importance throughout the latter half of the 20th Century, before merging with the Social Democratic Party in 1988 to form the present day...

, but was unsuccessful on both occasions. In 1906, the Johnstons moved to the hamlet of Poling, near Arundel

Arundel

Arundel is a market town and civil parish in the South Downs of West Sussex in the south of England. It lies south southwest of London, west of Brighton, and east of the county town of Chichester. Other nearby towns include Worthing east southeast, Littlehampton to the south and Bognor Regis to...

in West Sussex, where Harry Johnston largely concentrated on his literary endeavours. He took to writing novel

Novel

A novel is a book of long narrative in literary prose. The genre has historical roots both in the fields of the medieval and early modern romance and in the tradition of the novella. The latter supplied the present generic term in the late 18th century....

s, which were frequently short-lived, while his accounts of his own voyages through central Africa were rather more enduring. Some have put forward the unlikely theory that he was the principal model for 'The Man who loved Dickens' in the novel A Handful of Dust

A Handful of Dust

A Handful of Dust is a novel by Evelyn Waugh published in 1934. It is included in Modern Library List of Best 20th-Century Novels, and was chosen by TIME magazine as one of the one hundred best English-language novels from 1923 to present....

by Evelyn Waugh

Evelyn Waugh

Arthur Evelyn St. John Waugh , known as Evelyn Waugh, was an English writer of novels, travel books and biographies. He was also a prolific journalist and reviewer...

.

Worksop

Worksop is the largest town in the Bassetlaw district of Nottinghamshire, England on the River Ryton at the northern edge of Sherwood Forest. It is about east-south-east of the City of Sheffield and its population is estimated to be 39,800...

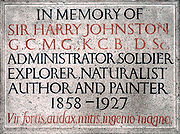

in Nottinghamshire. He was buried in the churchyard of St Nicholas, Poling, where there is a commemorative wall plaque within the nave of the church designed and cut by the Arts and Crafts

Arts and Crafts movement

Arts and Crafts was an international design philosophy that originated in England and flourished between 1860 and 1910 , continuing its influence until the 1930s...

sculptor and typeface designer, Eric Gill

Eric Gill

Arthur Eric Rowton Gill was a British sculptor, typeface designer, stonecutter and printmaker, who was associated with the Arts and Crafts movement...

- who lived in nearby Ditchling

Ditchling

Ditchling is a village and civil parish in the Lewes District of East Sussex, England. The village is contained within the boundaries of the South Downs National Park; the order confirming the establishment of the park was signed in Ditchling....

. The main typeface used on the plaque appears to be Gill's contemporaneously-designed Perpetua

Perpetua (typeface)

Perpetua is a typeface that was designed by English sculptor and typeface designer Eric Gill .Though not designed in the historical period of transitional type , Perpetua can be classified with transitional typefaces because of characteristics such as high stroke...

- designed in 1925, but not released until 1929 - while the lower-case typeface used for the Latin quote below is not presently recognised.

Harry Johnston was the very model of the multi-talented African explorer; he exhibited paintings, collected flora

Flora

Flora is the plant life occurring in a particular region or time, generally the naturally occurring or indigenous—native plant life. The corresponding term for animals is fauna.-Etymology:...

and fauna

Fauna

Fauna or faunæ is all of the animal life of any particular region or time. The corresponding term for plants is flora.Zoologists and paleontologists use fauna to refer to a typical collection of animals found in a specific time or place, e.g. the "Sonoran Desert fauna" or the "Burgess shale fauna"...

(he was instrumental in bringing the okapi

Okapi

The okapi , Okapia johnstoni, is a giraffid artiodactyl mammal native to the Ituri Rainforest, located in the northeast of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, in Central Africa...

to the attention of science), climbed mountains, wrote books, signed treaties, and ruled colonial governments. Like his fellow imperialists

Imperialism

Imperialism, as defined by Dictionary of Human Geography, is "the creation and/or maintenance of an unequal economic, cultural, and territorial relationships, usually between states and often in the form of an empire, based on domination and subordination." The imperialism of the last 500 years,...

he believed in British and European superiority over Africans, though he tended towards paternalistic governance rather than the use of brute force. These attitudes, which seem patronising today, were outlined in his book The Backward Peoples and Our Relations with Them (1920), but included his view that colonial rulers should try to understand the culture of the subjugated peoples. Consequently he was considered (by white settlers) as being unusually favourable towards the native peoples (for instance his administration was one of the first in British African colonies to train and employ Africans in the colonial service as clerks and skilled staff), and he had eventually fallen out with Cecil Rhodes as a result.

The falls at Mambidima on the Luapula River were named Johnston Falls by the British in his honour.

Books

- The River CongoCongo RiverThe Congo River is a river in Africa, and is the deepest river in the world, with measured depths in excess of . It is the second largest river in the world by volume of water discharged, though it has only one-fifth the volume of the world's largest river, the Amazon...

(1884) - The Kilema-Njaro Expedition (1886)

- British Central Africa (1897)

- The Colonization of Africa (1899)

- The Uganda Protectorate (1902)

- The Nile Quest: The Story of Exploration (1903)

- Liberia (1906)

- George GrenfellGeorge GrenfellGeorge Grenfell was an Cornish missionary and explorer.-Early years:...

and the Congo (1908) - The Negro in the New World (1910)

- A Comparative Study of the Bantu and Semi-Bantu Languages (1919, 1922)

- The Gay-Dombeys (1919) - a sequel to Dombey and SonDombey and SonDombey and Son is a novel by the Victorian author Charles Dickens. It was first published in monthly parts between October 1846 and April 1848 with the full title Dealings with the Firm of Dombey and Son: Wholesale, Retail and for Exportation...

by Charles DickensCharles DickensCharles John Huffam Dickens was an English novelist, generally considered the greatest of the Victorian period. Dickens enjoyed a wider popularity and fame than had any previous author during his lifetime, and he remains popular, having been responsible for some of English literature's most iconic... - Mrs. Warren's Daughter -- a sequel to Mrs. Warren's ProfessionMrs. Warren's ProfessionMrs Warren's Profession is a play written by George Bernard Shaw in 1893. The story centers on the relationship between Mrs Kitty Warren, a brothel owner, described by the author as "on the whole, a genial and fairly presentable old blackguard of a woman" and her daughter, Vivie...

by George Bernard ShawGeorge Bernard ShawGeorge Bernard Shaw was an Irish playwright and a co-founder of the London School of Economics. Although his first profitable writing was music and literary criticism, in which capacity he wrote many highly articulate pieces of journalism, his main talent was for drama, and he wrote more than 60... - The Backward Peoples and Our Relations with Them (1920)

- The Story of my Life (1923) - autobiography

- The Veneerings - a sequel to Our Mutual FriendOur Mutual FriendOur Mutual Friend is the last novel completed by Charles Dickens and is one of his most sophisticated works, combining psychological insight with social analysis. It centres on, in the words of critic J. Hillis Miller, "money, money, money, and what money can make of life" but is also about human...

by Charles DickensCharles DickensCharles John Huffam Dickens was an English novelist, generally considered the greatest of the Victorian period. Dickens enjoyed a wider popularity and fame than had any previous author during his lifetime, and he remains popular, having been responsible for some of English literature's most iconic...