Henry Hunt (politician)

Encyclopedia

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

radical speaker and agitator remembered as a pioneer of working-class radicalism

Radicalism (historical)

The term Radical was used during the late 18th century for proponents of the Radical Movement. It later became a general pejorative term for those favoring or seeking political reforms which include dramatic changes to the social order...

and an important influence on the later Chartist movement. He advocated parliamentary

Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body in the United Kingdom, British Crown dependencies and British overseas territories, located in London...

reform and the repeal of the Corn Laws

Corn Laws

The Corn Laws were trade barriers designed to protect cereal producers in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland against competition from less expensive foreign imports between 1815 and 1846. The barriers were introduced by the Importation Act 1815 and repealed by the Importation Act 1846...

.

Hunt was born in Upavon

Upavon

Upavon is a rural village in the English County of Wiltshire, England. As its name suggests, it is on the upper portions of the River Avon which runs from the north to the south through the village. It is situated about south of Pewsey, about southeast of the market town of Devizes, and about ...

, Wiltshire

Wiltshire

Wiltshire is a ceremonial county in South West England. It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset, Somerset, Hampshire, Gloucestershire, Oxfordshire and Berkshire. It contains the unitary authority of Swindon and covers...

and became a prosperous farmer. He was first drawn into radical politics during the Napoleonic Wars

Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars were a series of wars declared against Napoleon's French Empire by opposing coalitions that ran from 1803 to 1815. As a continuation of the wars sparked by the French Revolution of 1789, they revolutionised European armies and played out on an unprecedented scale, mainly due to...

, becoming a supporter of Francis Burdett. His talent for public speaking became noted in the electoral politics of Bristol

Bristol

Bristol is a city, unitary authority area and ceremonial county in South West England, with an estimated population of 433,100 for the unitary authority in 2009, and a surrounding Larger Urban Zone with an estimated 1,070,000 residents in 2007...

, where he denounced the complacency of both the Whigs

British Whig Party

The Whigs were a party in the Parliament of England, Parliament of Great Britain, and Parliament of the United Kingdom, who contested power with the rival Tories from the 1680s to the 1850s. The Whigs' origin lay in constitutional monarchism and opposition to absolute rule...

and the Tories, and proclaimed himself a supporter of democratic radicalism. It was thanks to his particular talents that a new programme beyond the narrow politics of the day made steady progress in the difficult years that followed the conclusion of the war with France.

Because of his rousing speeches at mass meetings held in Spa Fields

Spa Fields riots

The Spa Fields Riots were mass meetings that took place at Spa Fields, Islington, England on 15 November, 2 and 9 December 1816 between revolutionary Spenceans against the British government. The Spenceans had planned to encourage rioting at this meeting and then seize control of the British...

in London in 1816-17 he became known as the 'Orator', a term of disparagement accorded by his enemies. He embraced a programme that included annual parliaments and universal suffrage, promoted openly and with none of the conspiratorial element of the old Jacobin clubs

Jacobin (politics)

A Jacobin , in the context of the French Revolution, was a member of the Jacobin Club, a revolutionary far-left political movement. The Jacobin Club was the most famous political club of the French Revolution. So called from the Dominican convent where they originally met, in the Rue St. Jacques ,...

. The tactic he most favoured was that of 'mass pressure', which he felt, if given enough weight, could achieve reform without insurrection.

Although his efforts at mass politics

Mass politics

Mass politics is a political order resting on the emergence of mass political parties.The emergence of mass politics generally associated with the rise of mass society coinciding with the Industrial Revolution in the West around the time of President Andrew Jackson...

had the effect of radicalising large sections of the community unrepresented in Parliament, there were clear limits as to how far this could be taken. He was one of the scheduled speakers at the rally in Manchester

Manchester

Manchester is a city and metropolitan borough in Greater Manchester, England. According to the Office for National Statistics, the 2010 mid-year population estimate for Manchester was 498,800. Manchester lies within one of the UK's largest metropolitan areas, the metropolitan county of Greater...

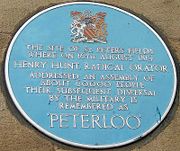

on 16 August 1819 that became the Peterloo Massacre

Peterloo Massacre

The Peterloo Massacre occurred at St Peter's Field, Manchester, England, on 16 August 1819, when cavalry charged into a crowd of 60,000–80,000 that had gathered to demand the reform of parliamentary representation....

, and the incident cost him more than two years in prison. The debacle at Peterloo, caused by an overreaction of the local Manchester authorities, added greatly to his prestige, but it advanced the cause not one step. Moral force was not sufficient in itself, and physical force entailed too great a risk. Although urged to do so after Peterloo, Hunt refused to give his approval to schemes for a full-scale insurrection. Thereby all momentum was lost, as more desperate souls turned to worn out cloak-and-dagger schemes, which surfaced in the Cato Street Conspiracy

Cato Street Conspiracy

The Cato Street Conspiracy was an attempt to murder all the British cabinet ministers and Prime Minister Lord Liverpool in 1820. The name comes from the meeting place near Edgware Road in London. The Cato Street Conspiracy is notable due to dissenting public opinions regarding the punishment of the...

.

Autobiography

An autobiography is a book about the life of a person, written by that person.-Origin of the term:...

. After his release he attempted to recover some of his lost fortune by beginning new business ventures in London, which included the production and marketing of a roasted corn Breakfast Powder, the "most salubrious and nourishing Beverage that can be substituted for the use of Tea and Coffee, which are always exciting, and frequently the most irritating to the Stomach and Bowels." He also made shoe-blacking bottles, which carried the slogan "Equal Laws, Equal Rights, Annual Parliaments, Universal Suffrage, and the Ballot." Synthetic coal, intended specifically for the French market, was another of his schemes. After the July Revolution

July Revolution

The French Revolution of 1830, also known as the July Revolution or in French, saw the overthrow of King Charles X of France, the French Bourbon monarch, and the ascent of his cousin Louis-Philippe, Duke of Orléans, who himself, after 18 precarious years on the throne, would in turn be overthrown...

in 1830 he sent samples to Gilbert du Motier, marquis de La Fayette

Gilbert du Motier, marquis de La Fayette

Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de La Fayette , often known as simply Lafayette, was a French aristocrat and military officer born in Chavaniac, in the province of Auvergne in south central France...

and other political heroes, along with fraternal greetings.

Business interests notwithstanding, he still found time for practical politics, fighting battles over a whole range of issues, and always pushing for reform and accountability. In 1830 he became a member of Parliament for Preston

Preston (UK Parliament constituency)

Preston is a borough constituency represented in the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It elects one Member of Parliament by the first past the post system of election.-Boundaries:...

defeating the future British Prime Minister

Prime minister

A prime minister is the most senior minister of cabinet in the executive branch of government in a parliamentary system. In many systems, the prime minister selects and may dismiss other members of the cabinet, and allocates posts to members within the government. In most systems, the prime...

Edward Stanley

Edward Smith-Stanley, 14th Earl of Derby

Edward George Geoffrey Smith-Stanley, 14th Earl of Derby, KG, PC was an English statesman, three times Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, and to date the longest serving leader of the Conservative Party. He was known before 1834 as Edward Stanley, and from 1834 to 1851 as Lord Stanley...

, but was defeated when standing for re-election in 1833. As a consistent champion of the working classes, a term he used with increasing frequency, he opposed the Whigs, both old and new, and the Reform Act 1832

Reform Act 1832

The Representation of the People Act 1832 was an Act of Parliament that introduced wide-ranging changes to the electoral system of England and Wales...

, which he believed did not go far enough in the extension of the franchise. He gave speeches addressed to the "Working Classes and no other", urging them to press for full equal rights. In 1832 he presented the first petition in support of women's suffrage to Parliament. It was received however with much ribald laughter and antagonism. Also in that year, he petitioned parliament on behalf of the radical preacher John Ward

John Ward (prophet)

John Ward , known as "Zion Ward", was an Irish preacher, mystic and self-styled prophet, active in England from around 1828-1835. He was one of those claiming to be the successor of prophetess Joanna Southcott after her death...

, who had been imprisoned for blasphemy.

In his opposition to the Reform Bill Orator Hunt revived the Great Northern Union, a pressure group he set up some years before, intended to unite the northern industrial workers behind a platform of full democratic reform; and it is in this specifically that the germs of Chartism can be detected. Worn out by his struggles he died in 1835.

A monument to Hunt was erected in 1842 by "the working people", in Every Street, Manchester, in Scholefield's Chapel Yard. A "spiral" march was held on the anniversary of Peterloo, from Piccadilly around the town past the Peterloo site, down to Deansgate and through Ancoats to the monument. The monument's stonework deteriorated and it was demolished in 1888.