History of Gnosticism

Encyclopedia

The history of Gnosticism is subject to a great deal of debate and interpretation. The complex nature of Gnostic teaching and the fact that much of the material relating to the schools comprising Gnosticism

has traditionally come from critiques by orthodox Christians

make it difficult to be precise about early sectarian gnostic systems, although Neoplatonists like Plotinus

also criticized "Gnostics."

Irenaeus

in his Adversus Haereses

described several different schools of 2nd-century gnosticism in disparaging and often sarcastic detail while contrasting them with Christianity to their detriment. Despite these problems, scholarly discussion of Gnosticism at first relied heavily on Irenaeus and other heresiologists, which arguably has led to an 'infiltration' of heresiological agendas into modern scholarship; this was not by choice, but because of a simple lack of alternative sources.

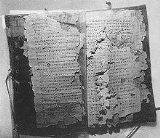

This state of affairs continued through to modern times; in 1945, however, there was a chance discovery of a cache of 4th-century Gnostic manuscripts near Nag Hammadi

, Egypt

. The texts, which had been sealed inside earthen jars, were discovered by a local man called Mohammed Ali, and now this collection of texts is known as the Nag Hammadi library

; this allowed for the modern study of undiluted 'Gnostic scripture' for the first time. The translation of the texts from Coptic

, their language of composition, into English and other modern languages took place in the years approaching 1977, when the full Nag Hammadi library was published in English translation. This has clarified recent discussions of gnosticism, though many would agree that the topic still remains fraught with difficulties.

At the same time, modern movements referencing ancient gnosticism have continued to develop, from origins in the popular new age

and occult

movements of the 19th century. Thus 'Gnosticism' is often ascribed to modern sects where initiates have access to certain arcana

. The strict usage of the term remains a historical one however, specifically indicating a set of ancient religious movements.

The word 'Gnosticism' is a 17thC construction first made by Henry More

, but is based on the use of the adjective "of knowledge", (Greek γνωστικός) by Irenaeus

(c.185 AD) to describe the school of Valentinus

However, gnosis itself refers to a very specialized form of knowledge, deriving both from the exact meaning of the original Greek term and its usage in Plato

nist philosophy

(see Plato's gnostikoi’ and gnostike episteme from Politicus (or Statesmen) 258e-267a). Gnosis also has a hermetic

understanding. In the Hellenic

world gnosis and hermetic understanding were exclusively pagan as one can see in the word being Koine Greek and deriving from Pagan Platonic philosophy. Platonic

and Pythagorian

modes of thinking spread Greek ideas and culture throughout the Hellenic world, introducing the mideastern peoples conquered by Alexander the Great to many of the concepts that were unique to Greek thinkers of the time (and vice versa). It should also be noted that Alexander made efforts to unite all conquered peoples under a common language and a common culture, which led to many cultures adopting Koine Greek

as a language for common communication in commerce between different ethnic and cultural groups.

One of the most important events of this era was the translation of the many Hebrew texts of what is now known as the Old Testament

into a single language (Koine Greek) in a single work (the Seventy or Septuagint). In addition, many of the Greek ideas of existence (hypostasis) and uniqueness or essence (ousia

) and most importantly rational mind (nous

) were introduced into Babylonian, Egyptian

, Libyan

, Roman

, Hebrew

, and other Mediterranean cultures, as was the concept that we exist within the mind of God, Noetic or Nous. This caused many of the educated and informed people of these cultures to incorporate these ideas and concepts into their own philosophical and religious belief systems. Gnosticism among those individuals who are called Gnostics, was one such example. Many of the first Gnostics may have been pagan and Hebrew (Egyptian, Babylonian and Hebrew), predating Christianity

.

Unlike modern English, ancient Greek was capable of discerning between several different forms of knowing. These different forms may be described in English as being propositional knowledge, indicative of knowledge acquired indirectly through the reports of others or otherwise by inference (such as "I know of George Bush" or "I know Berlin is in Germany"), and knowledge acquired by direct participation or acquaintance (such as "I know George Bush personally" or "I know Berlin, having visited").

Gnosis

(γνώσις) refers to knowledge of the second kind. Therefore, in a religious context, to be 'Gnostic' should be understood as being reliant not on knowledge

in a general sense, but as being specially receptive to mystical or esoteric experiences of direct participation with the divine. Gnosis refers to intimate personal knowledge and insight from experience. Indeed, in most Gnostic systems the sufficient cause of salvation

is this 'knowledge of' ('acquaintance with') the divine. This is commonly associated with a process of inward 'knowing' or self-exploration, comparable to that encouraged by Plotinus

(c. 205–270 CE). However, as may be seen, the term 'gnostic' also had precedent usage in several ancient philosophical

traditions, which must also be weighed in considering the very subtle implications of its appellation to a set of ancient religious groups (though currently there is no direct archaeological evidence to support such a claim outside of the Mediterranean).

in the Politicus (258e-267a), in which he compares the gnostike episteme ('understanding connected with knowledge') which denotes knowledge based on mathematical understanding or abstraction knowledge (see Kant

), to the praktike episteme ('understanding connected with practice'). Plato describes the ideal politician as the practitioner par excellence of the former, and his success is to be considered only in the light of his ability toward this ‘art of knowing’, irrespective of social rank. Hence any man, be he ruler or otherwise may thus become, as Plato puts it, ‘royal’. Here, gnostikos makes reference to an ability to possess certain knowledge, not the condition of possessing knowledge per se or the knowledge that is itself possessed, nor even, it might be further noted, to the individual who possesses it.

In ‘The History of the Term Gnostikos’ in The Rediscovery of Gnosticism (E.J. Brill, Leiden, 1981, 798–800) Morton Smith

lists users of ‘gnostikos’ in this manner as being Aristotle

, Strato of Lampsacus

, ‘a series of Pythagoreans

’, Philo Judaeus and Plutarch

, amongst others. Christoph Markschies notes in Gnosis: An Introduction (trans. John Bowden, T & T Clark, London, 2001) that the term was used extensively only within the Platonist tradition, and would not have had much relevance outside it.

Despite this, Plato's usage of the descriptive phrase 'royal' to denote the elevated position of the able gnostikoi, and the availability of such a position to all members of society regardless of rank, would have been greatly appealing to such early Christians as Clement (Titus Flavius Clementis

) of Alexandria, who happily described gnosis as the central goal of Christian faith. Despite this, Clement is not however typically considered a Gnostic in the modern sense.

Aristotle

, who was a student of Plato and later a teacher at Plato's academy, described the ideal life of success as being the one which is spent in theoretical contemplation (bios theoretikos). Thus, as with Clement, gnosis as such becomes the central goal of life, extending through the mode of morality into the realms of politics

and religion

. Philosophy, according to Aristotle, is a methodically ordered form of attaining this gnosis: 'Philosophy promises knowledge of being' (Alexander of Aphrodisias

, Commentary on the Metaphysics of Aristotle, c. 200 CE).

The ancient Gnosticism related to the texts found at Nag Hammadi and the various ancient reports on such Gnostics, therefore, could be described as but one of many ancient traditions which are dedicated to the pursuit of knowledge, and which supply teachings and methodologies that are supposed to aid in such a pursuit. The groups are often identified by a founder or teacher in the various ancient reports about Gnostics.

As with both the Platonist and the Aristotelian traditions, the pursuit of gnosis is the central occupation of life, and involves a measure of dedicated contemplation to attain. As with Clement, it may be surmised that the description of the gnostike episteme by Plato was appealing to early Gnostic formulators. Some early Gnostic movements emphasize the rarity of such knowledge, for example, some texts and reports associated with the Seth

ian gnostic tradition (see below).

Despite the above, the problem remains that the term 'Gnosticism' was rarely if ever self-applied by any group in antiquity; even if the suitability of the term might be argued from the discussion above, it remains for the most part a modern typological construction. As a result, the term may be said to draw attention to the doctrine of gnosis out of proportion to its actual importance to 'Gnostics' themselves.

In ancient times, Irenaeus

and Plotinus

both referred to the various sects as diverging from the Hellenistic Greek philosophical understanding. Hence Irenaeus and Plotinus refer to what they saw as distinctive among the various groups of gnostics.

On the other hand, 'Gnosticism' is still adjectivally applied to systems of belief which do not afford knowledge the special significance that is logically implied by the term. Such uses of the term 'Gnosticism' rely on other similarities, such as structural parallels in various texts and visions. This tactic could be said to stretch the category's usefulness in meaningful discussion in a broader context. In certain cases, such broad usage has also led to confusion between various ancient and modern usages of the term, even among scholars.

' Address to the Gnostics or Against the Gnostics is more properly known as 'Against those that affirm the creator of the kosmos

and the kosmos itself to be evil'. The text appears in the ninth tractate of the second Ennead

, the Enneads being the works of Plotinus as collated and edited by Porphyry

, his disciple. It is known that Plotinus' writing was poor, and that he detested revising and correcting his work, preferring to leave such tasks to others. The name was given to the text by Plotinus

as pointed out in the Life of Plotinus.

Also many Neoplatonic philosophers while not directly criticising gnosticism did however explicitly use demiurgic or creative teachings to bring about salvation to their followers. Pro demiurgic Neoplatonic philosophers included Porphyry

, Proclus

, Iamblichus of Chalcis

. Pre Neoplatonic philosopher and Neo pythagorian philosopher Numenius of Apamea

. The Demiurge

being Plato's creator of the material world demiurgic as to participate in the creative processes of the universe bringing one closer to the Demiurge or creator.

The formation of the text is as an address delivered by Plotinus to a number of his students, who have apparently been corrupted by ideas other than Plotinus' own. As such, the tract takes the form of an extended address by the philosopher, and he occasionally acknowledges the audience as intimates. Although Plotinus is very specific in that he states his target is not his students exclusively, but Gnostics so called.

The general tendency to view the text much as Porphyry's titles – both the abbreviated and the lengthier versions – summarize it has recently come under challenge. To do so makes several assumptions and is not the generally accept view since this contradicts the Life of Plotinus. Doubts concerning the accuracy of the abbreviated title in reflecting the text's central intentions might arise, especially when it is considered that the word 'Gnostic' is very seldom encountered in the text itself. Though Plotinus himself pointed out that he felt that the group should not garner too much attention. Also people might become confused because of the Platonic use of the word "gnostic" and then also this sectarian use of the word. This is why Plotinus' attack is direct and brief. In A. H. Armstrong

's translation of The Enneads, 'Gnostic' occurs only eleven times in the tractate in question, often as editorial emendations for neutral phrases such as 'they' (αύτούς) or 'the others' (των αλων). A. H. Armstrong is very clear in his introduction to the Against the Gnostics tract to clarify via the Nag Hammadi

that Plotinus was indeed attacking the secterians who claimed the Sethian cosmology as Plotinus' target.

Morton Smith has hypothesized that Porphyry was influenced in his chosen title by the success of Irenaeus

's Adversus Haereses, which was well known in Rome at the time; Porphyry thus appropriated the form of the title to describe a schismatic group, though recalling the discussion above, it would be likely that Porphyry would understand 'Gnostic' in a Platonist context, rather than a Christian one. The description of his opponent's libertinism, for example, does not sit well with the evidence of ascetic tendencies within Gnostic texts (see below), and this has been noted by Michael Allen Williams. Morton Smith

has taken the opposite position and used the Secret Gospel of Mark

as gnostic text to validate that certain gnostic secterians were indeed libertine, also see the Cainites

. Michael Williams does not address Morton Smith's views on gnosticism's libertinism and or The Secret Gospel of Mark, nor does he mention the references to libertines or antinomianism

made by Philo

(see On the Migration of Abraham 86–93), or R. Yohanan ben Zakkaiunder under the term Minuth. Michael Williams has pointed out that Plotinus arrives at this conclusion of libertinism by a process of ‘rhetorical magic’, rather than ‘direct observation’. Observing that ultimately only two moral choices pertain –either dedicating oneself to bodily pleasure or to the pursuit of virtue–, Plotinus reasons that, since his opponents appear uninterested in the operations of virtue, they must therefore despise 'all the laws of the world'. Michael Allen Williams

though does not call into question who Plotinus' target is. He affirms them as being the Gnostics secterians that Plotinus was attacking. Gnostics that would fall under the heading today as secterians of Gnosticism.

Thus the accusations of libertinism are not necessarily observations of Gnostic behaviour per se, but are rather hypotheses extrapolated from his opponent's apparently neglectful attitude to virtue.

This does not limit his attack on the core tenets of the Gnostic Sethian cosmology as the longer title of the tract reveals. Plotinus attacks his opponents as blasphemers and imbeciles who stole all of their truths from Plato.

Stating that the creation cosmology of Sophia and the demiurge "surpasses sheer folly".

Plotinus states of the mindset that if someone is a Gnostic, that they are already saved by God regardless of their behavior, this would lead to libertinism. One might compare the ‘rhetorical subterfuge’ of Irenaeus in Adversus Haereses: he creates a dilemma upon the horns of which he claims his opponents are caught, forcing them to accept one of ‘two equally unacceptable alternatives’ (Denis Minns, Irenaeus, London: Geoffrey Chapman, 1994, 26). Thus, by trapping his pupils within such a dilemma, Plotinus hopes to convince them of the inferiority of the learnings by which they have been corrupted.

Dr. Christos Evangeliou purposed the idea that the group of Gnostics that Plotinus was attacking in his "Against the Gnostics" were possibly Syncretic Christians, or Gnostic Christians, during the First International Conference on Neoplatonism and Gnosticism in the 1980s. Evangeliou forwarded this hypothesis because some of the same ways that Plotinus was criticizing the Gnostics, Porphyry

later used as ways to criticize Christianity, in Porphyry's Against Christianity. Evangeliou also noted that some things that Plotinus criticized the gnostics for could also be applied to orthodox Christianity. If Evangeliou still holds this to be true is unclear and it is not apparently reflected in some of his more current works. This was also addressed by Richard Wallis in his History of Philosophy. This dialogue was challenged (though indirectly) by other scholars of the field in light of the Nag Hammadi discovery, most importantly by A. H. Armstrong

.

who worked to chronicle those movements perceived to be deviating from the developing orthodox

church, and to refute their teachings as they did so, with the ultimate aim of demonstrating their moral inferiority. The problems with such sources are immediately apparent: given the avowed antagonism of such writers to that which they reported, could they be trusted to maintain accuracy, despite their bias

? The Nag Hammadi library generally confirms that the heresiologists' summaries of Gnosticism give an accurate, albeit incomplete and polemical, portrayal of the movement, its beliefs and practices.

The list below briefly details the works of several of the more significant of the heresiologists; however, the list could be expanded to contain Origen

, Clement of Alexandria

, Epiphanius of Salamis

, and others. The analytical tactics employed by each heresiologist will also be given, where possible.

(c. 100/114 – c. 162/168), the early Christian apologist, wrote the First Apology, addresses to Roman Emperor

Antoninus Pius

, which mentions his lost 'Compendium Against the Heretics', a work which reputedly reports on the activities of Simon Magus

, Menander

and Marcion; since this time, both Simon and Menander have been considered as 'proto-Gnostic' (Markschies, Gnosis, 37). Despite this paucity of surviving texts Justin Martyr remains a useful historical figure, as he allows us to determine the time and context in which the first gnostic systems arose. Outside of the earliest forms of gnosticism as indicted by the Apocalypse of Adam

which is pre-Christian. Marcion is popularly labelled a gnostic, however most scholars do not consider him a gnostic at all, for example, the Encyclopædia Britannica

article on Marcion clearly states: "In Marcion's own view, therefore, the founding of his church—to which he was first driven by opposition—amounts to a reformation of Christendom

through a return to the gospel of Christ and to Paul; nothing was to be accepted beyond that. This of itself shows that it is a mistake to reckon Marcion among the Gnostics. A dualist he certainly was, but he was not a Gnostic."

' central work, which was written c. 180–185 AD, is commonly known by the Latin

title Adversus Haereses

('Against Heresies'). The full title is Conviction and Refutation of Knowledge So-Called, and it is collected in five volumes. The work is apparently a reaction against Greek merchants who were apparently conducting an oratorial campaign concerning a quest for knowledge within Irenaeus' Gaul

ish bishopric

.

Irenaeus' general approach in Adversus Haereses was to identify Simon Magus

from Flavia Neapolis in Samaria

(modern-day Palestine

) as the inceptor of Gnosticism, 'its source and root' (Adversus Haereses, I.22.2). From there he charted an apparent spread of the teachings of Simon through the ancient 'knowers', as he calls them, into the teachings of Valentinus and other, contemporary Gnostic sects. This understanding of the transmission of Gnostic ideas, despite Irenaeus' certain antagonistic bias, is often utilized today, though it has been criticized.

Against the teachings of his opponents, which Irenaeus presented as confused and ill-organized, Irenaeus recommended a simple faith that all could follow, 'oriented on the criterion of truth that had come down in the church from the apostles to those in positions of responsibility' (Markschies, Gnosis, 30–31). Therefore Irenaeus' work might justifiably be seen as an early attempt by a Christian writer to posit the idea of a fully formed orthodoxy transmitted from the apostles directly after Christ's death and which in support possesses a rigorously defined hierarchical authority. From such a stable and superior authority heresies according divide by deviation from the norm it maintains, rather than developing alongside it by alternate yet related lines.

was an early Christian writer elected as the first Antipope

in 217. He died as a martyr

in 235. He was known for his polemical works against the Jews, pagans and heretics; the most important of these being the seven-volume Refutatio Omnium Haeresium ('Refutation Against all Heresies'), of which only fragments are known.

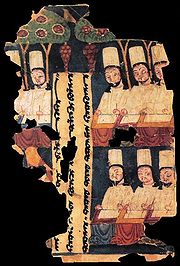

Of all the groups reported upon by Hippolytus, thirty-three are considered Gnostic by modern scholars, including 'the foreigners' and 'the Seth

people'. As well as this, Hippolytus presents individual teachers such as Simon, Valentinus

, Secundus

, Ptolemy

, Heracleon

, Marcus

and Colorbasus

; however, he rarely reproduces sources, instead tending only to report titles. Also of interest, a sect known to Hippolytus as the 'Naasenes

' frequently called themselves 'knowers': 'They take [their] name from the Hebrew word snake. Later they called themselves knowers, since they claimed that they alone knew the depths of wisdom' (Refutatio, V.6.3f).

Hippolytus considered the groups he surveyed to have become involved in Greek philosophy to their detriment. They had grievously misunderstood its foundations and thus had arrived at illogical constructions, through its influence becoming hopelessly confused (Markschies, Gnosis, 33).

(Quintus Septimius Florens Tertullianus, c. 155–230) was a prolific writer from Carthage

, the region that is now modern Tunisia

. He wrote a text entitled Adversus Valentinianos ('Against the Valentinians'), c. 206, as well as five books around 207–208 chronicling and refuting the teachings of Marcion.

The Nag Hammadi library is a collection of early Christian

Gnostic texts discovered near the Egyptian town of Nag Hammadi

in 1945. The writings in these codices comprised fifty-two mostly Gnostic tractates

; they also include three works belonging to the Corpus Hermeticum

and a partial translation of Plato

's Republic. The codices are currently housed in the Coptic Museum

in Cairo

.

Though the original language of composition was probably Greek

, the various codices contained in the collection were written in Coptic

. A 1st- or 2nd-century date of composition for the lost Greek originals has been proposed, though this is disputed; the manuscripts themselves date from the 3rd and 4th centuries.

For a full account of the discovery and translation of the Nag Hammadi library (which has been described as 'exciting as the contents of the find itself' (Markschies, Gnosis: An Introduction, 48)) see the Nag Hammadi library

article.

s they reported on, or transcribe their sacred texts, but instead gave us only titles and extended commentaries on their perceived heretical mistakes. Reconstructions were attempted from the available evidence, but the resulting portraits of gnosticism and its central texts were necessarily crude, and deeply suspect. The ability to overcome such problems provided by the Nag Hammadi codices need hardly be noted.

Of greatest difficulty was the fact that, prior to the publication of the codices, theological investigators, in order to proceed, could not help but to subscribe at least in part to the view of the heresiologists that gnosticism marked a heretical deviation from a fully formed orthodox Christianity in the three centuries immediately following Christ's death. The availability of original texts not only allowed an unsullied transmission of gnostic ideas, but also demonstrated the fluidity of early Christian scripture and, by extension, Christianity itself. As Layton notes 'the lack of uniformity in ancient Christian scripture in the early period is very striking, and it points to the substantial diversity within the Christian religion' (Layton, The Gnostic Scriptures, xviii).

Thus, although it is still correct to speak of early Christianity as a single tradition, it is also a complex network of competing sects and individual parties, which express their contrasting natures through differences in their scriptural interests. These differences may have arisen as much from differences in cultural

, linguistic

and social

milieus, the coexistence of essentially different theological conceptions of Jesus, as well as the differences in the philosophical or symbolic systems in which early Christian writers might express themselves. As such, the Nag Hammadi library offers a glimpse of the set of circulating texts that would have been of interest within a 'Gnostic' community (rather than as a gnostic canon in and of itself) and thus potentially provides an insight into the gnostic mind itself.

It was with the Council of Nicaea

in 325 (convened during the reign of the Emperor Constantine; 272–337) and the 3rd Synod of Carthage in 397, which progressively cemented Christianity as the officially sanctioned religion of the Eastern Roman Empire, that a structurally coherent and crystallized form of orthodox Christianity began to emerge. Though Christianity was not made the official religion of the Roman Empire until Theodosius I

391 AD. (Although, after the fall of the Western Roman Empire, even though many barbarian tribes were Christian, Christianity wasn't technically official until Charlemagne

, c800 AD, in the west). Central to the formation of orthodoxy was the creation of a binding and coherent scriptural 'canon', which was to be strictly observed by the adherents of that church. The Nag Hammadi library offers an intriguing source of texts whose intended exclusion as much drove the formation of the orthodox canon as did the desire to include certain other texts, now well-known. 'Orthodox Christian doctrine of the ancient world—and thus of the modern church—was partly conceived of as being what gnostic scripture was not (Layton, The Gnostic Scriptures; emphasis writer's own). Thus a study of Gnostic scripture might also obliquely increase our knowledge of nascent orthodoxy, the intentions of the orthodox formulators, the effect of social setting on early Christian expression, and the Judaic foundations it rests upon.

has sketched out a relationship between the various gnostic movements in his introduction to The Gnostic Scriptures (SCM Press, London, 1987). In this model, 'Classical Gnosticism' and 'The School of Thomas' antedated and influenced the development of Valentinus

, who was to found his own school of Gnosticism in both Alexandria

and Rome, whom Layton called 'the great [Gnostic] reformer' and 'the focal point' of Gnostic development. While in Alexandria, where he was born, Valentinus probably would have had contact with the Gnostic teacher Basilides

, and may have been influenced by him.

Valentinianism flourished throughout the early centuries of the common era: while Valentinus himself lived from ca

. 100–175 CE, a list of sectarians or heretics, composed in 388 CE, against whom Emperor Constantine intended legislation includes Valentinus (and, presumably, his inheritors). The school is also known to have been extremely popular: several varieties of their central myth are known, and we know of 'reports from outsiders from which the intellectual liveliness of the group is evident' (Markschies, Gnosis: An Introduction, 94). It is known that Valentinus' students, in further evidence of their intellectual activity, elaborated upon the teachings and materials they received from him (though the exact extent of their changes remains unknown), for example, in the version of the Valentinian myth brought to us through Ptolemy

.

Valentinianism might be described as the most elaborate and philosophically 'dense' form of the Syrian-Egyptian schools of Gnosticism, though it should be acknowledged that this in no way debarred other schools from attracting followers: Basilides' own school was popular also, and survived in Egypt

until the 4th century.

Simone Petrement, in A Separate God, in arguing for a Christian origin of Gnosticism, places Valentinus after Basilides, but before the Sethians. It is her assertion that Valentinus represented a moderation of the anti-Judaism

of the earlier Hellenized teachers; the demiurge, widely regarded to be a mythological depiction of the Old Testament God of the Hebrews, is depicted as more ignorant than evil. (See below.)

in his book Gnosis: The Nature & Structure of Gnosticism (Koehler and Amelang, Leipzig

, 1977), to explain the lineage of Persian Gnostic schools. The decline of Manicheism that occurred in Persia in the 5th century CE was too late to prevent the spread of the movement into the east and the west. In the west, the teachings of the school moved into Syria

, Northern Arabia, Egypt

and North Africa

(where Augustine

was a member of school from 373 to 382); from Syria it progressed still farther, into Palestine

, Asia Minor

and Armenia

. There is evidence for Manicheans in Rome and Dalmatia

in the 4th century, and also in Gaul

and Spain. The influence of Manicheanism was attacked by imperial elects and polemical writings, but the religion remained prevalent until the 6th century, and still exerted influence in the emergence of the Paulicians, Bogomils and Cathari in the Middle Ages.

In the east, Rudolph relates, Manicheanism was able to bloom, given that the religious monopoly position previously held by Christianity and Zoroastrianism

had been broken by nascent Islam. In the early years of the Arab conquest, Manicheanism again found followers in Persia (mostly amongst educated circles), but flourished most in Central Asia, to which it had spread through Iran. Here, in 762, Manicheanism became the state religion of the Uyghur Empire

. From this point Manichean influence spread even further into Central Asia, and according to Rudolph its influence may be detected in Tibet

and China, where it was strongly opposed by Confucianism

, and its followers were subject to a number of bloody repressions. Rudolph reports that despite this suppression Manichean traditions are reputed to have survived until the 17th century (based on the reports of Portuguese sailors).

, William Blake

, Aleister Crowley

, and Eric Voegelin

. This influence has apparently grown since the emergence and translation of the Nag Hammadi library (see above). See the article Gnosticism in modern times

for a fuller treatment; readers are also recommended to The Nag Hammadi Library in English, edited by James M. Robinson

, later editions of which contain an essay on 'The Modern Relevance of Gnosticism', by Richard Smith.

Gnosticism

Gnosticism is a scholarly term for a set of religious beliefs and spiritual practices common to early Christianity, Hellenistic Judaism, Greco-Roman mystery religions, Zoroastrianism , and Neoplatonism.A common characteristic of some of these groups was the teaching that the realisation of Gnosis...

has traditionally come from critiques by orthodox Christians

Christianity

Christianity is a monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus as presented in canonical gospels and other New Testament writings...

make it difficult to be precise about early sectarian gnostic systems, although Neoplatonists like Plotinus

Plotinus

Plotinus was a major philosopher of the ancient world. In his system of theory there are the three principles: the One, the Intellect, and the Soul. His teacher was Ammonius Saccas and he is of the Platonic tradition...

also criticized "Gnostics."

Irenaeus

Irenaeus

Saint Irenaeus , was Bishop of Lugdunum in Gaul, then a part of the Roman Empire . He was an early church father and apologist, and his writings were formative in the early development of Christian theology...

in his Adversus Haereses

On the Detection and Overthrow of the So-Called Gnosis

On the Detection and Overthrow of the So-Called Gnosis, today also called On the Detection and Overthrow of Knowledge Falsely So Called , commonly called Against Heresies , is a five-volume work written by St. Irenaeus in the 2nd century...

described several different schools of 2nd-century gnosticism in disparaging and often sarcastic detail while contrasting them with Christianity to their detriment. Despite these problems, scholarly discussion of Gnosticism at first relied heavily on Irenaeus and other heresiologists, which arguably has led to an 'infiltration' of heresiological agendas into modern scholarship; this was not by choice, but because of a simple lack of alternative sources.

This state of affairs continued through to modern times; in 1945, however, there was a chance discovery of a cache of 4th-century Gnostic manuscripts near Nag Hammadi

Nag Hammâdi

Nag Hammadi , is a city in Upper Egypt. Nag Hammadi was known as Chenoboskion in classical antiquity, meaning "geese grazing grounds". It is located on the west bank of the Nile in the Qena Governorate, about 80 kilometres north-west of Luxor....

, Egypt

Egypt

Egypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

. The texts, which had been sealed inside earthen jars, were discovered by a local man called Mohammed Ali, and now this collection of texts is known as the Nag Hammadi library

Nag Hammadi library

The Nag Hammadi library is a collection of early Christian Gnostic texts discovered near the Upper Egyptian town of Nag Hammadi in 1945. That year, twelve leather-bound papyrus codices buried in a sealed jar were found by a local peasant named Mohammed Ali Samman...

; this allowed for the modern study of undiluted 'Gnostic scripture' for the first time. The translation of the texts from Coptic

Coptic language

Coptic or Coptic Egyptian is the current stage of the Egyptian language, a northern Afro-Asiatic language spoken in Egypt until at least the 17th century. Egyptian began to be written using the Greek alphabet in the 1st century...

, their language of composition, into English and other modern languages took place in the years approaching 1977, when the full Nag Hammadi library was published in English translation. This has clarified recent discussions of gnosticism, though many would agree that the topic still remains fraught with difficulties.

At the same time, modern movements referencing ancient gnosticism have continued to develop, from origins in the popular new age

New Age

The New Age movement is a Western spiritual movement that developed in the second half of the 20th century. Its central precepts have been described as "drawing on both Eastern and Western spiritual and metaphysical traditions and then infusing them with influences from self-help and motivational...

and occult

Occult

The word occult comes from the Latin word occultus , referring to "knowledge of the hidden". In the medical sense it is used to refer to a structure or process that is hidden, e.g...

movements of the 19th century. Thus 'Gnosticism' is often ascribed to modern sects where initiates have access to certain arcana

Esotericism

Esotericism or Esoterism signifies the holding of esoteric opinions or beliefs, that is, ideas preserved or understood by a small group or those specially initiated, or of rare or unusual interest. The term derives from the Greek , a compound of : "within", thus "pertaining to the more inward",...

. The strict usage of the term remains a historical one however, specifically indicating a set of ancient religious movements.

The meaning of 'gnosis'

Gnosis (γνώσις) in ancient and modern Greek is the common feminine noun for "knowledge".The word 'Gnosticism' is a 17thC construction first made by Henry More

Henry More

Henry More FRS was an English philosopher of the Cambridge Platonist school.-Biography:Henry was born at Grantham and was schooled at The King's School, Grantham and at Eton College...

, but is based on the use of the adjective "of knowledge", (Greek γνωστικός) by Irenaeus

Irenaeus

Saint Irenaeus , was Bishop of Lugdunum in Gaul, then a part of the Roman Empire . He was an early church father and apologist, and his writings were formative in the early development of Christian theology...

(c.185 AD) to describe the school of Valentinus

Valentinus

Valentinus is a Roman masculine given name. It is derived from the Latin word "valens" meaning "healthy, strong". Valentinus may refer to:*Pope Valentine , pope for thirty or forty days in 827...

However, gnosis itself refers to a very specialized form of knowledge, deriving both from the exact meaning of the original Greek term and its usage in Plato

Plato

Plato , was a Classical Greek philosopher, mathematician, student of Socrates, writer of philosophical dialogues, and founder of the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. Along with his mentor, Socrates, and his student, Aristotle, Plato helped to lay the...

nist philosophy

Philosophy

Philosophy is the study of general and fundamental problems, such as those connected with existence, knowledge, values, reason, mind, and language. Philosophy is distinguished from other ways of addressing such problems by its critical, generally systematic approach and its reliance on rational...

(see Plato's gnostikoi’ and gnostike episteme from Politicus (or Statesmen) 258e-267a). Gnosis also has a hermetic

Hermeticism

Hermeticism or the Western Hermetic Tradition is a set of philosophical and religious beliefs based primarily upon the pseudepigraphical writings attributed to Hermes Trismegistus...

understanding. In the Hellenic

Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece is a civilization belonging to a period of Greek history that lasted from the Archaic period of the 8th to 6th centuries BC to the end of antiquity. Immediately following this period was the beginning of the Early Middle Ages and the Byzantine era. Included in Ancient Greece is the...

world gnosis and hermetic understanding were exclusively pagan as one can see in the word being Koine Greek and deriving from Pagan Platonic philosophy. Platonic

Platonism

Platonism is the philosophy of Plato or the name of other philosophical systems considered closely derived from it. In a narrower sense the term might indicate the doctrine of Platonic realism...

and Pythagorian

Pythagoras

Pythagoras of Samos was an Ionian Greek philosopher, mathematician, and founder of the religious movement called Pythagoreanism. Most of the information about Pythagoras was written down centuries after he lived, so very little reliable information is known about him...

modes of thinking spread Greek ideas and culture throughout the Hellenic world, introducing the mideastern peoples conquered by Alexander the Great to many of the concepts that were unique to Greek thinkers of the time (and vice versa). It should also be noted that Alexander made efforts to unite all conquered peoples under a common language and a common culture, which led to many cultures adopting Koine Greek

Koine Greek

Koine Greek is the universal dialect of the Greek language spoken throughout post-Classical antiquity , developing from the Attic dialect, with admixture of elements especially from Ionic....

as a language for common communication in commerce between different ethnic and cultural groups.

One of the most important events of this era was the translation of the many Hebrew texts of what is now known as the Old Testament

Old Testament

The Old Testament, of which Christians hold different views, is a Christian term for the religious writings of ancient Israel held sacred and inspired by Christians which overlaps with the 24-book canon of the Masoretic Text of Judaism...

into a single language (Koine Greek) in a single work (the Seventy or Septuagint). In addition, many of the Greek ideas of existence (hypostasis) and uniqueness or essence (ousia

Ousia

Ousia is the Ancient Greek noun formed on the feminine present participle of ; it is analogous to the English participle being, and the modern philosophy adjectival ontic...

) and most importantly rational mind (nous

Nous

Nous , also called intellect or intelligence, is a philosophical term for the faculty of the human mind which is described in classical philosophy as necessary for understanding what is true or real, very close in meaning to intuition...

) were introduced into Babylonian, Egyptian

Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt was an ancient civilization of Northeastern Africa, concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in what is now the modern country of Egypt. Egyptian civilization coalesced around 3150 BC with the political unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under the first pharaoh...

, Libyan

Libyan

A Libyan is a person or thing of, from, or related to Libya in North Africa.The term Libyan may also refer to:* A person from Libya, or of Libyan descent. For information about the Libyan people, see Demographics of Libya and Culture of Libya. For specific persons, see List of Libyans.* Libyan...

, Roman

Ancient Rome

Ancient Rome was a thriving civilization that grew on the Italian Peninsula as early as the 8th century BC. Located along the Mediterranean Sea and centered on the city of Rome, it expanded to one of the largest empires in the ancient world....

, Hebrew

Hebrews

Hebrews is an ethnonym used in the Hebrew Bible...

, and other Mediterranean cultures, as was the concept that we exist within the mind of God, Noetic or Nous. This caused many of the educated and informed people of these cultures to incorporate these ideas and concepts into their own philosophical and religious belief systems. Gnosticism among those individuals who are called Gnostics, was one such example. Many of the first Gnostics may have been pagan and Hebrew (Egyptian, Babylonian and Hebrew), predating Christianity

Christianity

Christianity is a monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus as presented in canonical gospels and other New Testament writings...

.

Unlike modern English, ancient Greek was capable of discerning between several different forms of knowing. These different forms may be described in English as being propositional knowledge, indicative of knowledge acquired indirectly through the reports of others or otherwise by inference (such as "I know of George Bush" or "I know Berlin is in Germany"), and knowledge acquired by direct participation or acquaintance (such as "I know George Bush personally" or "I know Berlin, having visited").

Gnosis

Gnosis

Gnosis is the common Greek noun for knowledge . In the context of the English language gnosis generally refers to the word's meaning within the spheres of Christian mysticism, Mystery religions and Gnosticism where it signifies 'spiritual knowledge' in the sense of mystical enlightenment.-Related...

(γνώσις) refers to knowledge of the second kind. Therefore, in a religious context, to be 'Gnostic' should be understood as being reliant not on knowledge

Knowledge

Knowledge is a familiarity with someone or something unknown, which can include information, facts, descriptions, or skills acquired through experience or education. It can refer to the theoretical or practical understanding of a subject...

in a general sense, but as being specially receptive to mystical or esoteric experiences of direct participation with the divine. Gnosis refers to intimate personal knowledge and insight from experience. Indeed, in most Gnostic systems the sufficient cause of salvation

Salvation

Within religion salvation is the phenomenon of being saved from the undesirable condition of bondage or suffering experienced by the psyche or soul that has arisen as a result of unskillful or immoral actions generically referred to as sins. Salvation may also be called "deliverance" or...

is this 'knowledge of' ('acquaintance with') the divine. This is commonly associated with a process of inward 'knowing' or self-exploration, comparable to that encouraged by Plotinus

Plotinus

Plotinus was a major philosopher of the ancient world. In his system of theory there are the three principles: the One, the Intellect, and the Soul. His teacher was Ammonius Saccas and he is of the Platonic tradition...

(c. 205–270 CE). However, as may be seen, the term 'gnostic' also had precedent usage in several ancient philosophical

Philosophy

Philosophy is the study of general and fundamental problems, such as those connected with existence, knowledge, values, reason, mind, and language. Philosophy is distinguished from other ways of addressing such problems by its critical, generally systematic approach and its reliance on rational...

traditions, which must also be weighed in considering the very subtle implications of its appellation to a set of ancient religious groups (though currently there is no direct archaeological evidence to support such a claim outside of the Mediterranean).

The Platonist and Aristotelian traditions

The first usage of the term ‘gnostikoi’, that is, 'those capable of knowing', was by PlatoPlato

Plato , was a Classical Greek philosopher, mathematician, student of Socrates, writer of philosophical dialogues, and founder of the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. Along with his mentor, Socrates, and his student, Aristotle, Plato helped to lay the...

in the Politicus (258e-267a), in which he compares the gnostike episteme ('understanding connected with knowledge') which denotes knowledge based on mathematical understanding or abstraction knowledge (see Kant

KANT

KANT is a computer algebra system for mathematicians interested in algebraic number theory, performing sophisticated computations in algebraic number fields, in global function fields, and in local fields. KASH is the associated command line interface...

), to the praktike episteme ('understanding connected with practice'). Plato describes the ideal politician as the practitioner par excellence of the former, and his success is to be considered only in the light of his ability toward this ‘art of knowing’, irrespective of social rank. Hence any man, be he ruler or otherwise may thus become, as Plato puts it, ‘royal’. Here, gnostikos makes reference to an ability to possess certain knowledge, not the condition of possessing knowledge per se or the knowledge that is itself possessed, nor even, it might be further noted, to the individual who possesses it.

In ‘The History of the Term Gnostikos’ in The Rediscovery of Gnosticism (E.J. Brill, Leiden, 1981, 798–800) Morton Smith

Morton Smith

Morton Smith was an American professor of ancient history at Columbia University. He is best known for his controversial discovery of the Mar Saba letter, a letter attributed to Clement of Alexandria containing excerpts from a Secret Gospel of Mark, during a visit to the monastery at Mar Saba in...

lists users of ‘gnostikos’ in this manner as being Aristotle

Aristotle

Aristotle was a Greek philosopher and polymath, a student of Plato and teacher of Alexander the Great. His writings cover many subjects, including physics, metaphysics, poetry, theater, music, logic, rhetoric, linguistics, politics, government, ethics, biology, and zoology...

, Strato of Lampsacus

Strato of Lampsacus

Strato of Lampsacus was a Peripatetic philosopher, and the third director of the Lyceum after the death of Theophrastus...

, ‘a series of Pythagoreans

Pythagoras

Pythagoras of Samos was an Ionian Greek philosopher, mathematician, and founder of the religious movement called Pythagoreanism. Most of the information about Pythagoras was written down centuries after he lived, so very little reliable information is known about him...

’, Philo Judaeus and Plutarch

Plutarch

Plutarch then named, on his becoming a Roman citizen, Lucius Mestrius Plutarchus , c. 46 – 120 AD, was a Greek historian, biographer, essayist, and Middle Platonist known primarily for his Parallel Lives and Moralia...

, amongst others. Christoph Markschies notes in Gnosis: An Introduction (trans. John Bowden, T & T Clark, London, 2001) that the term was used extensively only within the Platonist tradition, and would not have had much relevance outside it.

Despite this, Plato's usage of the descriptive phrase 'royal' to denote the elevated position of the able gnostikoi, and the availability of such a position to all members of society regardless of rank, would have been greatly appealing to such early Christians as Clement (Titus Flavius Clementis

Clement of Alexandria

Titus Flavius Clemens , known as Clement of Alexandria , was a Christian theologian and the head of the noted Catechetical School of Alexandria. Clement is best remembered as the teacher of Origen...

) of Alexandria, who happily described gnosis as the central goal of Christian faith. Despite this, Clement is not however typically considered a Gnostic in the modern sense.

Aristotle

Aristotle

Aristotle was a Greek philosopher and polymath, a student of Plato and teacher of Alexander the Great. His writings cover many subjects, including physics, metaphysics, poetry, theater, music, logic, rhetoric, linguistics, politics, government, ethics, biology, and zoology...

, who was a student of Plato and later a teacher at Plato's academy, described the ideal life of success as being the one which is spent in theoretical contemplation (bios theoretikos). Thus, as with Clement, gnosis as such becomes the central goal of life, extending through the mode of morality into the realms of politics

Politics

Politics is a process by which groups of people make collective decisions. The term is generally applied to the art or science of running governmental or state affairs, including behavior within civil governments, but also applies to institutions, fields, and special interest groups such as the...

and religion

Religion

Religion is a collection of cultural systems, belief systems, and worldviews that establishes symbols that relate humanity to spirituality and, sometimes, to moral values. Many religions have narratives, symbols, traditions and sacred histories that are intended to give meaning to life or to...

. Philosophy, according to Aristotle, is a methodically ordered form of attaining this gnosis: 'Philosophy promises knowledge of being' (Alexander of Aphrodisias

Alexander of Aphrodisias

Alexander of Aphrodisias was a Peripatetic philosopher and the most celebrated of the Ancient Greek commentators on the writings of Aristotle. He was a native of Aphrodisias in Caria, and lived and taught in Athens at the beginning of the 3rd century, where he held a position as head of the...

, Commentary on the Metaphysics of Aristotle, c. 200 CE).

The ancient Gnosticism related to the texts found at Nag Hammadi and the various ancient reports on such Gnostics, therefore, could be described as but one of many ancient traditions which are dedicated to the pursuit of knowledge, and which supply teachings and methodologies that are supposed to aid in such a pursuit. The groups are often identified by a founder or teacher in the various ancient reports about Gnostics.

As with both the Platonist and the Aristotelian traditions, the pursuit of gnosis is the central occupation of life, and involves a measure of dedicated contemplation to attain. As with Clement, it may be surmised that the description of the gnostike episteme by Plato was appealing to early Gnostic formulators. Some early Gnostic movements emphasize the rarity of such knowledge, for example, some texts and reports associated with the Seth

Seth

Seth , in Judaism, Christianity and Islam, is the third listed son of Adam and Eve and brother of Cain and Abel, who are the only other of their children mentioned by name...

ian gnostic tradition (see below).

Despite the above, the problem remains that the term 'Gnosticism' was rarely if ever self-applied by any group in antiquity; even if the suitability of the term might be argued from the discussion above, it remains for the most part a modern typological construction. As a result, the term may be said to draw attention to the doctrine of gnosis out of proportion to its actual importance to 'Gnostics' themselves.

In ancient times, Irenaeus

Irenaeus

Saint Irenaeus , was Bishop of Lugdunum in Gaul, then a part of the Roman Empire . He was an early church father and apologist, and his writings were formative in the early development of Christian theology...

and Plotinus

Plotinus

Plotinus was a major philosopher of the ancient world. In his system of theory there are the three principles: the One, the Intellect, and the Soul. His teacher was Ammonius Saccas and he is of the Platonic tradition...

both referred to the various sects as diverging from the Hellenistic Greek philosophical understanding. Hence Irenaeus and Plotinus refer to what they saw as distinctive among the various groups of gnostics.

On the other hand, 'Gnosticism' is still adjectivally applied to systems of belief which do not afford knowledge the special significance that is logically implied by the term. Such uses of the term 'Gnosticism' rely on other similarities, such as structural parallels in various texts and visions. This tactic could be said to stretch the category's usefulness in meaningful discussion in a broader context. In certain cases, such broad usage has also led to confusion between various ancient and modern usages of the term, even among scholars.

Neoplatonism and Plotinus' Address to the Gnostics

The text which has come to be known as PlotinusPlotinus

Plotinus was a major philosopher of the ancient world. In his system of theory there are the three principles: the One, the Intellect, and the Soul. His teacher was Ammonius Saccas and he is of the Platonic tradition...

' Address to the Gnostics or Against the Gnostics is more properly known as 'Against those that affirm the creator of the kosmos

Cosmos

In the general sense, a cosmos is an orderly or harmonious system. It originates from the Greek term κόσμος , meaning "order" or "ornament" and is antithetical to the concept of chaos. Today, the word is generally used as a synonym of the word Universe . The word cosmos originates from the same root...

and the kosmos itself to be evil'. The text appears in the ninth tractate of the second Ennead

Enneads

The Six Enneads, sometimes abbreviated to The Enneads or Enneads , is the collection of writings of Plotinus, edited and compiled by his student Porphyry . Plotinus was a student of Ammonius Saccas and they were founders of Neoplatonism...

, the Enneads being the works of Plotinus as collated and edited by Porphyry

Porphyry (philosopher)

Porphyry of Tyre , Porphyrios, AD 234–c. 305) was a Neoplatonic philosopher who was born in Tyre. He edited and published the Enneads, the only collection of the work of his teacher Plotinus. He also wrote many works himself on a wide variety of topics...

, his disciple. It is known that Plotinus' writing was poor, and that he detested revising and correcting his work, preferring to leave such tasks to others. The name was given to the text by Plotinus

Plotinus

Plotinus was a major philosopher of the ancient world. In his system of theory there are the three principles: the One, the Intellect, and the Soul. His teacher was Ammonius Saccas and he is of the Platonic tradition...

as pointed out in the Life of Plotinus.

Also many Neoplatonic philosophers while not directly criticising gnosticism did however explicitly use demiurgic or creative teachings to bring about salvation to their followers. Pro demiurgic Neoplatonic philosophers included Porphyry

Porphyry (philosopher)

Porphyry of Tyre , Porphyrios, AD 234–c. 305) was a Neoplatonic philosopher who was born in Tyre. He edited and published the Enneads, the only collection of the work of his teacher Plotinus. He also wrote many works himself on a wide variety of topics...

, Proclus

Proclus

Proclus Lycaeus , called "The Successor" or "Diadochos" , was a Greek Neoplatonist philosopher, one of the last major Classical philosophers . He set forth one of the most elaborate and fully developed systems of Neoplatonism...

, Iamblichus of Chalcis

Iamblichus of Chalcis

Iamblichus, also known as Iamblichus Chalcidensis, was an Assyrian Neoplatonist philosopher who determined the direction taken by later Neoplatonic philosophy...

. Pre Neoplatonic philosopher and Neo pythagorian philosopher Numenius of Apamea

Numenius of Apamea

Numenius of Apamea was a Greek philosopher, who lived in Apamea in Syria and flourished during the latter half of the 2nd century AD. He was a Neopythagorean and forerunner of the Neoplatonists.- Philosophy :...

. The Demiurge

Demiurge

The demiurge is a concept from the Platonic, Neopythagorean, Middle Platonic, and Neoplatonic schools of philosophy for an artisan-like figure responsible for the fashioning and maintenance of the physical universe. The term was subsequently adopted by the Gnostics...

being Plato's creator of the material world demiurgic as to participate in the creative processes of the universe bringing one closer to the Demiurge or creator.

The formation of the text is as an address delivered by Plotinus to a number of his students, who have apparently been corrupted by ideas other than Plotinus' own. As such, the tract takes the form of an extended address by the philosopher, and he occasionally acknowledges the audience as intimates. Although Plotinus is very specific in that he states his target is not his students exclusively, but Gnostics so called.

The general tendency to view the text much as Porphyry's titles – both the abbreviated and the lengthier versions – summarize it has recently come under challenge. To do so makes several assumptions and is not the generally accept view since this contradicts the Life of Plotinus. Doubts concerning the accuracy of the abbreviated title in reflecting the text's central intentions might arise, especially when it is considered that the word 'Gnostic' is very seldom encountered in the text itself. Though Plotinus himself pointed out that he felt that the group should not garner too much attention. Also people might become confused because of the Platonic use of the word "gnostic" and then also this sectarian use of the word. This is why Plotinus' attack is direct and brief. In A. H. Armstrong

A. H. Armstrong

Arthur Hilary Armstrong FBA was an English educator and author. Armstrong is recognized as one of the foremost authorities on the philosophical teachings of Plotinus ca. 205–270 CE. His multi-volume translation of the philosopher's teachings is regarded as an essential tool of classical studies.-...

's translation of The Enneads, 'Gnostic' occurs only eleven times in the tractate in question, often as editorial emendations for neutral phrases such as 'they' (αύτούς) or 'the others' (των αλων). A. H. Armstrong is very clear in his introduction to the Against the Gnostics tract to clarify via the Nag Hammadi

Nag Hammâdi

Nag Hammadi , is a city in Upper Egypt. Nag Hammadi was known as Chenoboskion in classical antiquity, meaning "geese grazing grounds". It is located on the west bank of the Nile in the Qena Governorate, about 80 kilometres north-west of Luxor....

that Plotinus was indeed attacking the secterians who claimed the Sethian cosmology as Plotinus' target.

Morton Smith has hypothesized that Porphyry was influenced in his chosen title by the success of Irenaeus

Irenaeus

Saint Irenaeus , was Bishop of Lugdunum in Gaul, then a part of the Roman Empire . He was an early church father and apologist, and his writings were formative in the early development of Christian theology...

's Adversus Haereses, which was well known in Rome at the time; Porphyry thus appropriated the form of the title to describe a schismatic group, though recalling the discussion above, it would be likely that Porphyry would understand 'Gnostic' in a Platonist context, rather than a Christian one. The description of his opponent's libertinism, for example, does not sit well with the evidence of ascetic tendencies within Gnostic texts (see below), and this has been noted by Michael Allen Williams. Morton Smith

Morton Smith

Morton Smith was an American professor of ancient history at Columbia University. He is best known for his controversial discovery of the Mar Saba letter, a letter attributed to Clement of Alexandria containing excerpts from a Secret Gospel of Mark, during a visit to the monastery at Mar Saba in...

has taken the opposite position and used the Secret Gospel of Mark

Secret Gospel of Mark

The Secret Gospel of Mark is a putative non-canonical Christian gospel known exclusively from the Mar Saba letter, which describes Secret Mark as an expanded version of the canonical Gospel of Mark with some episodes elucidated, written for an initiated elite.In 1973 Morton Smith , professor of...

as gnostic text to validate that certain gnostic secterians were indeed libertine, also see the Cainites

Cainites

The Cainites, or Cainians, were a Gnostic and Antinomian sect who were known to worship Cain as the first victim of the Demiurge Jehovah, the deity of the Tanakh , who was identified by many groups of gnostics as evil...

. Michael Williams does not address Morton Smith's views on gnosticism's libertinism and or The Secret Gospel of Mark, nor does he mention the references to libertines or antinomianism

Antinomianism

Antinomianism is defined as holding that, under the gospel dispensation of grace, moral law is of no use or obligation because faith alone is necessary to salvation....

made by Philo

Philo

Philo , known also as Philo of Alexandria , Philo Judaeus, Philo Judaeus of Alexandria, Yedidia, "Philon", and Philo the Jew, was a Hellenistic Jewish Biblical philosopher born in Alexandria....

(see On the Migration of Abraham 86–93), or R. Yohanan ben Zakkaiunder under the term Minuth. Michael Williams has pointed out that Plotinus arrives at this conclusion of libertinism by a process of ‘rhetorical magic’, rather than ‘direct observation’. Observing that ultimately only two moral choices pertain –either dedicating oneself to bodily pleasure or to the pursuit of virtue–, Plotinus reasons that, since his opponents appear uninterested in the operations of virtue, they must therefore despise 'all the laws of the world'. Michael Allen Williams

Michael Allen Williams

Rethinking "Gnosticism": An Argument for Dismantling a Dubious Category , is a 1999 book by Michael Allen Williams.This is one of the first critical works that goes about comparing the established academic definitions of gnosticism to the now acquired Nag Hammadi texts...

though does not call into question who Plotinus' target is. He affirms them as being the Gnostics secterians that Plotinus was attacking. Gnostics that would fall under the heading today as secterians of Gnosticism.

Thus the accusations of libertinism are not necessarily observations of Gnostic behaviour per se, but are rather hypotheses extrapolated from his opponent's apparently neglectful attitude to virtue.

This does not limit his attack on the core tenets of the Gnostic Sethian cosmology as the longer title of the tract reveals. Plotinus attacks his opponents as blasphemers and imbeciles who stole all of their truths from Plato.

Stating that the creation cosmology of Sophia and the demiurge "surpasses sheer folly".

Plotinus states of the mindset that if someone is a Gnostic, that they are already saved by God regardless of their behavior, this would lead to libertinism. One might compare the ‘rhetorical subterfuge’ of Irenaeus in Adversus Haereses: he creates a dilemma upon the horns of which he claims his opponents are caught, forcing them to accept one of ‘two equally unacceptable alternatives’ (Denis Minns, Irenaeus, London: Geoffrey Chapman, 1994, 26). Thus, by trapping his pupils within such a dilemma, Plotinus hopes to convince them of the inferiority of the learnings by which they have been corrupted.

Dr. Christos Evangeliou purposed the idea that the group of Gnostics that Plotinus was attacking in his "Against the Gnostics" were possibly Syncretic Christians, or Gnostic Christians, during the First International Conference on Neoplatonism and Gnosticism in the 1980s. Evangeliou forwarded this hypothesis because some of the same ways that Plotinus was criticizing the Gnostics, Porphyry

Porphyry (philosopher)

Porphyry of Tyre , Porphyrios, AD 234–c. 305) was a Neoplatonic philosopher who was born in Tyre. He edited and published the Enneads, the only collection of the work of his teacher Plotinus. He also wrote many works himself on a wide variety of topics...

later used as ways to criticize Christianity, in Porphyry's Against Christianity. Evangeliou also noted that some things that Plotinus criticized the gnostics for could also be applied to orthodox Christianity. If Evangeliou still holds this to be true is unclear and it is not apparently reflected in some of his more current works. This was also addressed by Richard Wallis in his History of Philosophy. This dialogue was challenged (though indirectly) by other scholars of the field in light of the Nag Hammadi discovery, most importantly by A. H. Armstrong

A. H. Armstrong

Arthur Hilary Armstrong FBA was an English educator and author. Armstrong is recognized as one of the foremost authorities on the philosophical teachings of Plotinus ca. 205–270 CE. His multi-volume translation of the philosopher's teachings is regarded as an essential tool of classical studies.-...

.

Heresiologists and Gnostic detractors

Prior to the discovery of the Nag Hammadi library in 1945 (arguably until its translation and eventual publication in 1977), Gnosticism was known primarily only through the works of heresiologists, Church FathersChurch Fathers

The Church Fathers, Early Church Fathers, Christian Fathers, or Fathers of the Church were early and influential theologians, eminent Christian teachers and great bishops. Their scholarly works were used as a precedent for centuries to come...

who worked to chronicle those movements perceived to be deviating from the developing orthodox

Orthodox Christianity

The term Orthodox Christianity may refer to:* the Eastern Orthodox Church and its various geographical subdivisions...

church, and to refute their teachings as they did so, with the ultimate aim of demonstrating their moral inferiority. The problems with such sources are immediately apparent: given the avowed antagonism of such writers to that which they reported, could they be trusted to maintain accuracy, despite their bias

Bias

Bias is an inclination to present or hold a partial perspective at the expense of alternatives. Bias can come in many forms.-In judgement and decision making:...

? The Nag Hammadi library generally confirms that the heresiologists' summaries of Gnosticism give an accurate, albeit incomplete and polemical, portrayal of the movement, its beliefs and practices.

The list below briefly details the works of several of the more significant of the heresiologists; however, the list could be expanded to contain Origen

Origen

Origen , or Origen Adamantius, 184/5–253/4, was an early Christian Alexandrian scholar and theologian, and one of the most distinguished writers of the early Church. As early as the fourth century, his orthodoxy was suspect, in part because he believed in the pre-existence of souls...

, Clement of Alexandria

Clement of Alexandria

Titus Flavius Clemens , known as Clement of Alexandria , was a Christian theologian and the head of the noted Catechetical School of Alexandria. Clement is best remembered as the teacher of Origen...

, Epiphanius of Salamis

Epiphanius of Salamis

Epiphanius of Salamis was bishop of Salamis at the end of the 4th century. He is considered a saint and a Church Father by both the Eastern Orthodox and Catholic Churches. He gained a reputation as a strong defender of orthodoxy...

, and others. The analytical tactics employed by each heresiologist will also be given, where possible.

Justin

Justin MartyrJustin Martyr

Justin Martyr, also known as just Saint Justin , was an early Christian apologist. Most of his works are lost, but two apologies and a dialogue survive. He is considered a saint by the Roman Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church....

(c. 100/114 – c. 162/168), the early Christian apologist, wrote the First Apology, addresses to Roman Emperor

Roman Emperor

The Roman emperor was the ruler of the Roman State during the imperial period . The Romans had no single term for the office although at any given time, a given title was associated with the emperor...

Antoninus Pius

Antoninus Pius

Antoninus Pius , also known as Antoninus, was Roman Emperor from 138 to 161. He was a member of the Nerva-Antonine dynasty and the Aurelii. He did not possess the sobriquet "Pius" until after his accession to the throne...

, which mentions his lost 'Compendium Against the Heretics', a work which reputedly reports on the activities of Simon Magus

Simon Magus

Simon the Sorcerer or Simon the Magician, in Latin Simon Magus, was a Samaritan magus or religious figure and a convert to Christianity, baptised by Philip the Apostle, whose later confrontation with Peter is recorded in . The sin of simony, or paying for position and influence in the church, is...

, Menander

Menander

Menander , Greek dramatist, the best-known representative of Athenian New Comedy, was the son of well-to-do parents; his father Diopeithes is identified by some with the Athenian general and governor of the Thracian Chersonese known from the speech of Demosthenes De Chersoneso...

and Marcion; since this time, both Simon and Menander have been considered as 'proto-Gnostic' (Markschies, Gnosis, 37). Despite this paucity of surviving texts Justin Martyr remains a useful historical figure, as he allows us to determine the time and context in which the first gnostic systems arose. Outside of the earliest forms of gnosticism as indicted by the Apocalypse of Adam

Apocalypse of Adam

The Apocalypse of Adam discovered in 1945 as part of the Nag Hammadi library is a Gnostic work written in Coptic. It has no necessary references to Christianity and it is accordingly debated whether it is a Christian Gnostic work or an example of Jewish Gnosticism...

which is pre-Christian. Marcion is popularly labelled a gnostic, however most scholars do not consider him a gnostic at all, for example, the Encyclopædia Britannica

Encyclopædia Britannica

The Encyclopædia Britannica , published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., is a general knowledge English-language encyclopaedia that is available in print, as a DVD, and on the Internet. It is written and continuously updated by about 100 full-time editors and more than 4,000 expert...

article on Marcion clearly states: "In Marcion's own view, therefore, the founding of his church—to which he was first driven by opposition—amounts to a reformation of Christendom

Christendom

Christendom, or the Christian world, has several meanings. In a cultural sense it refers to the worldwide community of Christians, adherents of Christianity...

through a return to the gospel of Christ and to Paul; nothing was to be accepted beyond that. This of itself shows that it is a mistake to reckon Marcion among the Gnostics. A dualist he certainly was, but he was not a Gnostic."

Irenaeus

IrenaeusIrenaeus

Saint Irenaeus , was Bishop of Lugdunum in Gaul, then a part of the Roman Empire . He was an early church father and apologist, and his writings were formative in the early development of Christian theology...

' central work, which was written c. 180–185 AD, is commonly known by the Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

title Adversus Haereses

On the Detection and Overthrow of the So-Called Gnosis

On the Detection and Overthrow of the So-Called Gnosis, today also called On the Detection and Overthrow of Knowledge Falsely So Called , commonly called Against Heresies , is a five-volume work written by St. Irenaeus in the 2nd century...

('Against Heresies'). The full title is Conviction and Refutation of Knowledge So-Called, and it is collected in five volumes. The work is apparently a reaction against Greek merchants who were apparently conducting an oratorial campaign concerning a quest for knowledge within Irenaeus' Gaul

Gaul

Gaul was a region of Western Europe during the Iron Age and Roman era, encompassing present day France, Luxembourg and Belgium, most of Switzerland, the western part of Northern Italy, as well as the parts of the Netherlands and Germany on the left bank of the Rhine. The Gauls were the speakers of...

ish bishopric

Diocese

A diocese is the district or see under the supervision of a bishop. It is divided into parishes.An archdiocese is more significant than a diocese. An archdiocese is presided over by an archbishop whose see may have or had importance due to size or historical significance...

.

Irenaeus' general approach in Adversus Haereses was to identify Simon Magus

Simon Magus

Simon the Sorcerer or Simon the Magician, in Latin Simon Magus, was a Samaritan magus or religious figure and a convert to Christianity, baptised by Philip the Apostle, whose later confrontation with Peter is recorded in . The sin of simony, or paying for position and influence in the church, is...

from Flavia Neapolis in Samaria

Samaria

Samaria, or the Shomron is a term used for a mountainous region roughly corresponding to the northern part of the West Bank.- Etymology :...

(modern-day Palestine

Palestine

Palestine is a conventional name, among others, used to describe the geographic region between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River, and various adjoining lands....

) as the inceptor of Gnosticism, 'its source and root' (Adversus Haereses, I.22.2). From there he charted an apparent spread of the teachings of Simon through the ancient 'knowers', as he calls them, into the teachings of Valentinus and other, contemporary Gnostic sects. This understanding of the transmission of Gnostic ideas, despite Irenaeus' certain antagonistic bias, is often utilized today, though it has been criticized.

Against the teachings of his opponents, which Irenaeus presented as confused and ill-organized, Irenaeus recommended a simple faith that all could follow, 'oriented on the criterion of truth that had come down in the church from the apostles to those in positions of responsibility' (Markschies, Gnosis, 30–31). Therefore Irenaeus' work might justifiably be seen as an early attempt by a Christian writer to posit the idea of a fully formed orthodoxy transmitted from the apostles directly after Christ's death and which in support possesses a rigorously defined hierarchical authority. From such a stable and superior authority heresies according divide by deviation from the norm it maintains, rather than developing alongside it by alternate yet related lines.

Hippolytus

HippolytusHippolytus (writer)

Hippolytus of Rome was the most important 3rd-century theologian in the Christian Church in Rome, where he was probably born. Photios I of Constantinople describes him in his Bibliotheca Hippolytus of Rome (170 – 235) was the most important 3rd-century theologian in the Christian Church in Rome,...

was an early Christian writer elected as the first Antipope

Antipope

An antipope is a person who opposes a legitimately elected or sitting Pope and makes a significantly accepted competing claim to be the Pope, the Bishop of Rome and leader of the Roman Catholic Church. At times between the 3rd and mid-15th century, antipopes were typically those supported by a...

in 217. He died as a martyr

Martyr

A martyr is somebody who suffers persecution and death for refusing to renounce, or accept, a belief or cause, usually religious.-Meaning:...

in 235. He was known for his polemical works against the Jews, pagans and heretics; the most important of these being the seven-volume Refutatio Omnium Haeresium ('Refutation Against all Heresies'), of which only fragments are known.

Of all the groups reported upon by Hippolytus, thirty-three are considered Gnostic by modern scholars, including 'the foreigners' and 'the Seth

Seth