History of the Federal Reserve System

Encyclopedia

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

Federal Reserve System

Federal Reserve System

The Federal Reserve System is the central banking system of the United States. It was created on December 23, 1913 with the enactment of the Federal Reserve Act, largely in response to a series of financial panics, particularly a severe panic in 1907...

from its creation to the present.

Central banking in the United States prior to the Federal Reserve

The Federal Reserve System is the third central banking system in the United States' history. The First Bank of the United StatesFirst Bank of the United States

The First Bank of the United States is a National Historic Landmark located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania within Independence National Historical Park.-Banking History:...

(1791–1811) and the Second Bank of the United States

Second Bank of the United States

The Second Bank of the United States was chartered in 1816, five years after the First Bank of the United States lost its own charter. The Second Bank of the United States was initially headquartered in Carpenters' Hall, Philadelphia, the same as the First Bank, and had branches throughout the...

(1816–1836) each had 20-year charters, and both issued currency, made commercial loans, accepted deposits, purchased securities, had multiple branches, and acted as fiscal agents for the U.S. Treasury. In both banks the Federal Government was required to purchase 20% of the bank's capital stock and appoint 20% of the directors. Thus majority control was in the hands of private investors who purchased the rest of the stock. The banks were opposed by state-chartered banks, who saw them as very large competitors, and by many who understood them to be banking cartels which compelled to them servitude of the common man

Common man

Common man may refer to:*Common people*Champion of the Common Man*"Common Man progrum" on sport hosted by Dan Cole*The cartoon character by R K Laxman, The Common Man*The Common Man , the 1975 French film...

. President Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson was the seventh President of the United States . Based in frontier Tennessee, Jackson was a politician and army general who defeated the Creek Indians at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend , and the British at the Battle of New Orleans...

vetoed legislation to renew the Second Bank of the United States, starting a period of free banking

Free banking

Free banking refers to a monetary arrangement in which banks are subject to no special regulations beyond those applicable to most enterprises, and in which they also are free to issue their own paper currency...

. Jackson staked his second term on the issue of central banking stating, "Every monopoly and all exclusive privileges are granted at the expense of the public, which ought to receive a fair equivalent. The many millions which this act proposes to bestow on the stockholders of the existing bank must come directly or indirectly out of the earnings of the American people."

In 1863, as a means to help finance the Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

, a system of national banks was instituted by the National Currency Act. The banks each had the power to issue standardized national bank notes based on United States bonds held by the bank. The Act was totally revised in 1864 and later named as the National-Bank Act, or National Banking Act

National Banking Act

The National Banking Acts of 1863 and 1864 were two United States federal laws that established a system of national charters for banks, and created the United States National Banking System. They encouraged development of a national currency backed by bank holdings of U.S...

, as it is popularly known. The administration of the new national banking system was vested in the newly created Office of the Comptroller of the Currency and its chief administrator, the Comptroller of the Currency. The Office, which still exists today, examines and supervises all banks chartered nationally and is a part of the U.S. Treasury Department.

The Federal Reserve Act

National bank currency was considered inelastic because it was based on the fluctuating value of U.S. Treasury bonds rather than the growing desire for easy credit. If Treasury bond prices declined, a national bank had to reduce the amount of currency it had in circulation by either refusing to make new loans or by calling in loans it had made already. The related liquidity problem was largely caused by an immobile, pyramidal reserve system, in which nationally chartered country banks were required to set aside their reserves in reserve city banks, which in turn were required to have reserves in central city banks. During planting season country banks needed to call in their reserves, and during the harvest season they would add to their reserves. A national bank whose reserves were being drained would replace its reserves by selling stocks and bonds, by borrowing from a clearing houseClearing house (finance)

A clearing house is a financial institution that provides clearing and settlement services for financial and commodities derivatives and securities transactions...

or by calling in loans. As there was little in the way of deposit insurance, if a bank was rumored to be having liquidity problems then this might cause many people to remove their funds from the bank. Because of the crescendo effect of banks which lent more than their assets could cover, during the last quarter of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, the United States economy went through a series of financial panics.

The National Monetary Commission

A particularly severe panic in 1907Panic of 1907

The Panic of 1907, also known as the 1907 Bankers' Panic, was a financial crisis that occurred in the United States when the New York Stock Exchange fell almost 50% from its peak the previous year. Panic occurred, as this was during a time of economic recession, and there were numerous runs on...

provided the motivation for renewed demands for banking and currency reform. The following year Congress enacted the Aldrich-Vreeland Act

Aldrich-Vreeland Act

The Aldrich–Vreeland Act was passed in response to the Panic of 1907 and established the National Monetary Commission, which recommended the Federal Reserve Act of 1913....

which provided for an emergency currency and established the National Monetary Commission

National Monetary Commission

National Monetary Commission was a study group created by the Aldrich Vreeland Act of 1908. After the Panic of 1907 American bankers turned to Europe for ideas on how to operate a central bank. Senator Nelson Aldrich, Republican leader of the Senate, personally led a team of experts to major...

to study banking and currency reform.

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

's banking system, he came away believing that a centralized bank was better than the government-issued bond system that he had previously supported. Centralized banking was met with much opposition from politicians, who were suspicious of a central bank and who charged that Aldrich was biased due to his close ties to wealthy bankers such as J.P. Morgan and his daughter's marriage to John D. Rockefeller, Jr.

John D. Rockefeller, Jr.

John Davison Rockefeller, Jr. was a major philanthropist and a pivotal member of the prominent Rockefeller family. He was the sole son among the five children of businessman and Standard Oil industrialist John D. Rockefeller and the father of the five famous Rockefeller brothers...

In 1910, Aldrich and executives representing the banks of J.P. Morgan, Rockefeller, and Kuhn, Loeb & Co.

Kuhn, Loeb & Co.

Kuhn, Loeb & Co. was a bulge bracket, investment bank founded in 1867 by Abraham Kuhn and Solomon Loeb. Under the leadership of Jacob H. Schiff, it grew to be one of the most influential investment banks in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, financing America's expanding railways and growth...

, secluded themselves for 10 days at Jekyll Island

Jekyll Island

Jekyll Island is an island off the coast of the U.S. state of Georgia, in Glynn County; it is one of the Sea Islands and one of the Golden Isles of Georgia. The city of Brunswick, Georgia, the Marshes of Glynn, and several other islands, including the larger St. Simons Island, are nearby...

, Georgia

Georgia (U.S. state)

Georgia is a state located in the southeastern United States. It was established in 1732, the last of the original Thirteen Colonies. The state is named after King George II of Great Britain. Georgia was the fourth state to ratify the United States Constitution, on January 2, 1788...

. The executives included Frank A. Vanderlip

Frank A. Vanderlip

Frank A. Vanderlip was an American banker. From 1897-1901, Vanderlip was the Assistant Secretary of Treasury for President of the United States William McKinley's second term. In that office he negotiated with National City Bank a $200 million loan to the government to finance the Spanish...

, president of the National City Bank of New York, associated with the Rockefellers; Henry Davison, senior partner of J.P. Morgan Company; Charles D. Norton, president of the First National Bank of New York; and Col. Edward House, who would later become President Woodrow Wilson's closest adviser and founder of the Council on Foreign Relations

Council on Foreign Relations

The Council on Foreign Relations is an American nonprofit nonpartisan membership organization, publisher, and think tank specializing in U.S. foreign policy and international affairs...

. There, Paul Warburg

Paul Warburg

Paul Moritz Warburg was a German-born American banker and early advocate of the U.S. Federal Reserve system.- Early life :...

of Kuhn, Loeb, & Co. directed the proceedings and wrote the primary features of what would be called the Aldrich Plan. Warburg would later write that "The matter of a uniform discount rate (interest rate) was discussed and settled at Jekyll Island." Vanderlip wrote in his 1935 autobiography From Farmboy to Financier :

I was as secretive, indeed I was as furtive as any conspirator. Discovery, we knew, simply must not happen, or else all our time and effort would have been wasted. If it were to be exposed that our particular group had got together and written a banking bill, that bill would have no chance whatever of passage by Congress…I do not feel it is any exaggeration to speak of our secret expedition to Jekyll Island as the occasion of the actual conception of what eventually became the Federal Reserve System.”

Despite meeting in secret, from both the public and the government, the importance of the Jekyll Island meeting was revealed three years after the Federal Reserve Act was passed, when journalist Bertie Charles Forbes wrote an article about the "hunting trip" in 1916.

The 1911-12 Republican plan was proposed by Aldrich to solve the banking dilemma, a goal which was supported by the American Bankers’ Association. It provided for one great central bank, the National Reserve Association, with a capital of at least $100 million and with 15 branches in various sections. The branches were to be controlled by the member banks on a basis of their capitalization. The National Reserve Association would issue currency, based on gold and commercial paper, that would be the liability of the bank and not of the government. It would also carry a portion of member banks’ reserves, determine discount reserves, buy and sell on the open market, and hold the deposits of the federal government. The branches and businessmen of each of the 15 districts would elect thirty out of the 39 members of the board of directors of the National Reserve Association.

Aldrich fought for a private monopoly with little government influence, but conceded that the government should be represented on the Board of Directors. Aldrich then presented what was commonly called the "Aldrich Plan" -- which called for establishment of a "National Reserve Association" -- to the National Monetary Commission. Most Republicans

Republican Party (United States)

The Republican Party is one of the two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Democratic Party. Founded by anti-slavery expansion activists in 1854, it is often called the GOP . The party's platform generally reflects American conservatism in the U.S...

and Wall Street

Wall Street

Wall Street refers to the financial district of New York City, named after and centered on the eight-block-long street running from Broadway to South Street on the East River in Lower Manhattan. Over time, the term has become a metonym for the financial markets of the United States as a whole, or...

bankers favored the Aldrich Plan, but it lacked enough support in the bipartisan Congress to pass.

Because the bill was introduced by Aldrich, considered the epitome of the "Eastern establishment," the bill received little support and was derided by southerners and westerners who believed that wealthy families and large corporations ran the country and would thus run the proposed National Reserve Association. The National Board of Trade appointed Warburg as head of a committee to persuade Americans to support the plan. The committee set up offices in the then-45 states and distributed printed materials about the central bank. The Nebraska

Nebraska

Nebraska is a state on the Great Plains of the Midwestern United States. The state's capital is Lincoln and its largest city is Omaha, on the Missouri River....

n populist and frequent Democratic presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan was an American politician in the late-19th and early-20th centuries. He was a dominant force in the liberal wing of the Democratic Party, standing three times as its candidate for President of the United States...

said of the plan: "Big financiers are back of the Aldrich currency scheme." He asserted that if it passed, big bankers would "then be in complete control of everything through the control of our national finances."

There was also Republican opposition to the Aldrich Plan. Republican Sen. Robert M. LaFollette and Rep. Charles Lindbergh Sr.

Charles August Lindbergh

Charles August Lindbergh Sr. was a United States Congressman from Minnesota's 6th congressional district from 1907 to 1917...

both spoke out against the favoritism that they contended the bill granted to Wall Street. "The Aldrich Plan is the Wall Street Plan…I have alleged that there is a 'Money Trust'", said Lindbergh. "The Aldrich plan is a scheme plainly in the interest of the Trust". In response, Rep. Arsène Pujo

Arsène Pujo

Arsène Paulin Pujo , was a member of the United States House of Representatives best known for chairing the "Pujo Committee", which sought to expose an anticompetitive conspiracy among some of the nation's most powerful financial interests.-Biography:Pujo practiced law in Louisiana, and was elected...

, a Democrat from Oklahoma, obtained congressional authorization to form and chair a subcommittee (the Pujo Committee

Pujo Committee

The Pujo Committee was a United States congressional subcommittee which was formed between May 1912 and January 1913 to investigate the so-called "money trust", a community of Wall Street bankers and financiers that exerted powerful control over the nation's finances. After a resolution introduced...

) within the House Committee Banking Committee, to conduct investigative hearings on the alleged "Money Trust." The hearings continued for a full year and were led by the Subcommittee's counsel, Democratic lawyer Samuel Untermyer

Samuel Untermyer

Samuel Untermyer Samuel Untermyer Samuel Untermyer (March 6, 1858 – March 16, 1940, although some sources cite March 2, 1858, and even others, June 6, 1858 also known as Samuel Untermeyer was a Jewish-American lawyer and civic leader as well as a self-made millionaire. He was born in...

, who later also assisted in preparing the Federal Reserve Act

Federal Reserve Act

The Federal Reserve Act is an Act of Congress that created and set up the Federal Reserve System, the central banking system of the United States of America, and granted it the legal authority to issue Federal Reserve Notes and Federal Reserve Bank Notes as legal tender...

. The "Pujo hearings" convinced much of the populace that America's money largely rested in the hands of a select few on Wall Street. The Subcommittee issued a report saying:

"If by a 'money trust' is meant an established and well-defined identity and community of interest between a few leaders of finance…which has resulted in a vast and growing concentration of control of money and credit in the hands of a comparatively few men…the condition thus described exists in this country today...To us the peril is manifest...When we find...the same man a director in a half dozen or more banks and trust companies all located in the same section of the same city, doing the same class of business and with a like set of associates similarly situated all belonging to the same group and representing the same class of interests, all further pretense of competition is useless.... "

Seen as a "Money Trust" plan, the Aldrich Plan was opposed by the Democratic Party as was stated in its 1912 campaign platform, but the platform also supported a revision of banking laws that would protect the public from financial panics and "the domination of what is known as the "Money Trust." During the 1912 election the Democractic Party took control of the Presidency and both chambers of Congress. The newly elected President, Woodrow Wilson

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson was the 28th President of the United States, from 1913 to 1921. A leader of the Progressive Movement, he served as President of Princeton University from 1902 to 1910, and then as the Governor of New Jersey from 1911 to 1913...

,was committed to banking and currency reform, but it took a great deal of his political influence to get an acceptable plan passed as the Federal Reserve Act in 1913. Wilson thought the Aldrich plan was perhaps "60-70% correct". When Virginia Rep. Carter Glass, chairman of the House Committee on Banking and Currency, presented his bill to President-elect Wilson, Wilson said that the plan must be amended to contain a Federal Reserve Board appointed by the executive branch to maintain control over the bankers.

After Wilson presented the bill to Congress, a group of Democratic congressmen revolted, led by Representative Robert Henry

Robert Henry

Robert Henry was a Scottish historian.Born into a farming family at St. Ninians, Stirlingshire, Henry was educated at Stirling High School and the University of Edinburgh. After teaching at Annan, he entered the Church of Scotland, becoming minister at New Greyfriars in Edinburgh in 1768...

of Texas, demanding that the "Money Trust" be destroyed before it could undertake major currency reforms. They particularly objected to the idea of regional banks having to operate without the implicit government protections that large, so-called money-center banks would enjoy. The group almost succeeded in killing the bill, but were mollified by Wilson's promises to propose antitrust legislation after the bill had passed and by Bryan's support of the bill.

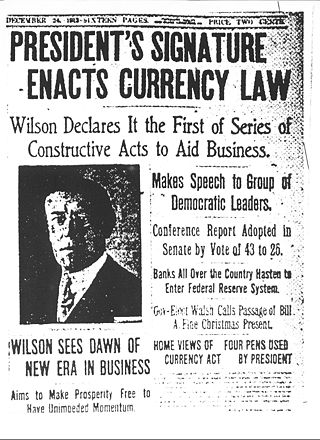

The enactment of the Federal Reserve Act

After months of hearings, amendments, and debates the Federal Reserve Act passed Congress on a Sunday two days before Christmas when most of Congress was on vacation. Most every Democrat was in support of and most Republicans were against it. As noted in a paper by the American Institute of Economic Research:

In its final form, the Federal Reserve Act represented a compromise among three political groups. Most Republicans (and the Wall Street bankers) favored the Aldrich Plan that came out of Jekyll Island. Progressive Democrats demanded a reserve system and currency supply owned and controlled by the Government in order to counter the "money trust" and destroy the existing concentration of credit resources in Wall Street. Conservative Democrats proposed a decentralized reserve system, owned and controlled privately but free of Wall Street domination. No group got exactly what it wanted. But the Aldrich plan more nearly represented the compromise position between the two Democrat extremes, and it was closest to the final legislation passed.

Frank Vanderlip, one of the Jekyll Island attendees and the President of National City Bank, wrote in his autobiography:

"Although the Aldrich Federal Reserve Plan was defeated when it bore the name Aldrich, nevertheless its essential points were all contained in the plan that was finally adopted."

Ironically, in October 1913, two months before the enactment of the Federal Reserve Act, Frank Vanderlip proposed before the Senate Banking Committee his own competing plan to the Federal Reserve System, one with a single central bank controlled by the Federal government, which almost derailed the legislation then being considered and already passed by the U.S. House of Representatives. Aldrich himself stated strong opposition to the currency plan passed by the House.

However, the former point was also made by Republican Representative Charles Lindbergh Sr.

Charles August Lindbergh

Charles August Lindbergh Sr. was a United States Congressman from Minnesota's 6th congressional district from 1907 to 1917...

of Minnesota, one of the most vocal opponents of the bill, who on the day the House agreed to the Federal Reserve Act told his colleagues:

"But the Federal reserve board have no power whatever to regulate the rates of interest that bankers may charge borrowers of money. This is the Aldrich bill in disguise, the difference being that by this bill the Government issues the money, whereas by the Aldrich bill the issue was controlled by the banks...Wall Street will control the money as easily through this bill as they have heretofore."(Congressional Record, v. 51, page 1447, Dec. 22, 1913)

Republican Congressman Victor Murdock

Victor Murdock

Victor Murdock was a U.S. Republican politician and newspaper editor.He was born in Burlingame, Kansas. He was elected as a Republican to the United States House of Representatives from Kansas to fill the vacancy caused by the resignation of Chester I. Long and served from May 26, 1903 to March...

of Kansas, who voted for the bill, told Congress on that same day:

"I do not blind myself to the fact that this measure will not be effectual as a remedy for a great national evil – the concentrated control of credit...The Money Trust has not passed [died]...You rejected the specific remedies of the Pujo committee, chief among them, the prohibition of interlocking directorates. He [your enemy] will not cease fighting...at some half-baked enactment...You struck a weak half-blow, and time will show that you have lost. You could have struck a full blow and you would have won."

In order to get the Federal Reserve Act passed, Wilson needed the support of populist William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan was an American politician in the late-19th and early-20th centuries. He was a dominant force in the liberal wing of the Democratic Party, standing three times as its candidate for President of the United States...

, who was credited with ensuring Wilson's nomination by dramatically throwing his support Wilson's way at the 1912 Democratic convention. Wilson appointed Bryan as his Secretary of State. Bryan served as leader of the agrarian wing of the party and had argued for unlimited coinage of silver in his "Cross of Gold Speech" at the 1896 Democratic convention. Bryan and the agrarians wanted a government-owned central bank which could print paper money whenever Congress wanted, and thought the plan gave bankers too much power to print the government's currency. Wilson sought the advice of prominent lawyer Louis Brandeis

Louis Brandeis

Louis Dembitz Brandeis ; November 13, 1856 – October 5, 1941) was an Associate Justice on the Supreme Court of the United States from 1916 to 1939.He was born in Louisville, Kentucky, to Jewish immigrant parents who raised him in a secular mode...

to make the plan more amenable to the agrarian wing of the party; Brandeis agreed with Bryan. Wilson convinced them that because Federal Reserve notes were obligations of the government and because the President would appoint the members of the Federal Reserve Board, the plan fit their demands. However, Bryan soon became disillusioned with the system. In the November 1923 issue of "Hearst's Magazine" Bryan wrote that "The Federal Reserve Bank that should have been the farmer's greatest protection has become his greatest foe."

Southerners and westerners learned from Wilson that the system was decentralized into 12 districts and surely would weaken New York and strengthen the hinterlands. Sen. Robert L. Owen

Robert L. Owen

Robert Latham Owen, Jr. was one of the first two U.S. senators from Oklahoma. He served in the Senate between 1907 and 1925...

of Oklahoma

Oklahoma

Oklahoma is a state located in the South Central region of the United States of America. With an estimated 3,751,351 residents as of the 2010 census and a land area of 68,667 square miles , Oklahoma is the 28th most populous and 20th-largest state...

eventually relented to speak in favor of the bill, arguing that the nation's currency was already under too much control by New York elites, whom he alleged had singlehandedly conspired to cause the 1907 Panic.

Large bankers thought the legislation gave the government too much control over markets and private business dealings. The New York Times called the Act the "Oklahoma idea, the Nebraska idea"-- referring to Owen and Bryan's involvement.

However, several Congressmen, including Owen, Lindbergh, LaFollette, and Murdock claimed that the New York bankers feigned their disapproval of the bill in hopes of inducing Congress to pass it. The day before the bill was passed, Murdock told Congress:

"You allowed the special interests by pretended dissatisfaction with the measure to bring about a sham battle, and the sham battle was for the purpose of diverting you people from the real remedy, and they diverted you. The Wall Street bluff has worked."

When Wilson signed the Federal Reserve Act on December 23, 1913, he said he felt grateful for having had a part "in completing a work ... of lasting benefit for the country," knowing that it took a great deal of compromise and expenditure of his own political capital to get it enacted. This was in keeping with the general plan of action he made in his First Inaugural Address on March 4, 1913, in which he stated:

We shall deal with our economic system as it is and as it may be modified, not as it might be if we had a clean sheet of paper to write upon; and step-by-step we shall make it what it should be, in the spirit of those who question their own wisdom and seek counsel and knowledge, not shallow self-satisfaction or the excitement of excursions we can not tell.

While a system of 12 regional banks was designed so as not to give eastern bankers too much influence over the new bank, in practice, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York

Federal Reserve Bank of New York

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York is one of the 12 Federal Reserve Banks of the United States. It is located at 33 Liberty Street, New York, NY. It is responsible for the Second District of the Federal Reserve System, which encompasses New York state, the 12 northern counties of New Jersey,...

became "first among equals

First Among Equals

First Among Equals is a 1984 novel by British author Jeffrey Archer, which follows the careers and personal lives of four fictional British politicians from 1964 to 1991, with each vying to become Prime...

". The New York Fed, for example, is solely responsible for conducting open market operations, at the direction of the Federal Open Market Committee. Democratic Congressman Carter Glass

Carter Glass

Carter Glass was a newspaper publisher and politician from Lynchburg, Virginia. He served many years in Congress as a member of the Democratic Party. As House co-sponsor, he played a central role in the development of the 1913 Glass-Owen Act that created the Federal Reserve System. Glass...

sponsored and wrote the eventual legislation, and his home state capital of Richmond, Virginia, was made a district headquarters. Democratic Senator James A. Reed

James A. Reed

James Alexander Reed was an American Democratic Party politician from Missouri.-Biography:Reed was born on a farm in Richland County, Ohio. He moved with his family to Cedar Rapids, Iowa at the age of 3. He went to public schools and attended Coe College...

of Missouri obtained two districts for his state. However, the 1914 report of the Federal Reserve Organization Committee, which clearly laid out the rationale for their decisions on establishing Reserve Bank districts in 1914, showed that it was based almost entirely upon current correspondent banking relationships. To quell Elihu Root's

Elihu Root

Elihu Root was an American lawyer and statesman and the 1912 recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize. He was the prototype of the 20th century "wise man", who shuttled between high-level government positions in Washington, D.C...

objections to possible inflation, the passed bill included provisions that the bank must hold at least 40% of its outstanding loans in gold. (In later years, to stimulate short-term economic activity, Congress would amend the act to allow more discretion in the amount of gold that must be redeemed by the Bank.) Critics of the time (later joined by economist Milton Friedman

Milton Friedman

Milton Friedman was an American economist, statistician, academic, and author who taught at the University of Chicago for more than three decades...

) suggested that Glass's legislation was almost entirely based on the Aldrich Plan that had been derided as giving too much power to elite bankers. Glass denied copying Aldrich's plan. In 1922, he told Congress, "no greater misconception was ever projected in this Senate Chamber."

Wilson named Warburg and other prominent experts to direct the new system, which began operations in 1915 and played a major role in financing the Allied and American war efforts. Warburg at first refused the appointment, citing America's opposition to a "Wall Street man", but when World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

broke out he accepted. He was the only appointee asked to appear before the Senate, whose members questioned him about his interests in the central bank and his ties to Kuhn, Loeb, & Co.'s "money trusts".

Post Bretton-Woods era

In July 1979, Paul VolckerPaul Volcker

Paul Adolph Volcker, Jr. is an American economist. He was the Chairman of the Federal Reserve under United States Presidents Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan from August 1979 to August 1987. He is widely credited with ending the high levels of inflation seen in the United States in the 1970s and...

was nominated, by President Carter

Jimmy Carter

James Earl "Jimmy" Carter, Jr. is an American politician who served as the 39th President of the United States and was the recipient of the 2002 Nobel Peace Prize, the only U.S. President to have received the Prize after leaving office...

, as Chairman of the Federal Reserve Board amid roaring inflation. He tightened the money supply, and by 1986 inflation had fallen sharply. In October 1979 the Federal Reserve announced a policy of "targeting" money aggregates

Money supply

In economics, the money supply or money stock, is the total amount of money available in an economy at a specific time. There are several ways to define "money," but standard measures usually include currency in circulation and demand deposits .Money supply data are recorded and published, usually...

and bank reserves in its struggle with double-digit inflation.

In January 1987, with retail inflation at only 1%, the Federal Reserve announced it was no longer going to use money-supply aggregates, such as M2, as guidelines for controlling inflation, even though this method had been in use from 1979, apparently with great success. Before 1980, interest rates were used as guidelines; inflation was severe. The Fed complained that the aggregates were confusing. Volcker was chairman until August 1987, whereupon Alan Greenspan

Alan Greenspan

Alan Greenspan is an American economist who served as Chairman of the Federal Reserve of the United States from 1987 to 2006. He currently works as a private advisor and provides consulting for firms through his company, Greenspan Associates LLC...

assumed the mantle, seven months after monetary aggregate policy had changed.

2001 Recession to Present

From early 2001 to mid 2003 the Federal Reserve lowered its interest rates 13 times, from 6.25 to 1.00%, to fight recessionRecession

In economics, a recession is a business cycle contraction, a general slowdown in economic activity. During recessions, many macroeconomic indicators vary in a similar way...

. In November 2002, rates were cut to 1.75, and many interest rates went below the inflation

Inflation

In economics, inflation is a rise in the general level of prices of goods and services in an economy over a period of time.When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services. Consequently, inflation also reflects an erosion in the purchasing power of money – a...

rate. On June 25, 2003, the federal funds rate was lowered to 1.00%, its lowest nominal rate since July, 1958, when the overnight rate averaged 0.68%. Starting at the end of June 2004, the Federal Reserve System raised the target interest rate and then continued to do so 17 straight times.

In March 2006, the Federal Reserve ceased to make public M3, because the costs of collecting this data outweighed the benefits. M3 includes all of M2 (which includes M1) plus large-denomination ($100,000 +) time deposits, balances in institutional money funds, repurchase liabilities issued by depository institutions, and Eurodollars held by U.S. residents at foreign branches of U.S. banks as well as at all banks in the United Kingdom and Canada.

2008 subprime mortgage crisis

Due to a credit crunch caused by the sub-prime mortgage crisisSubprime mortgage crisis

The U.S. subprime mortgage crisis was one of the first indicators of the late-2000s financial crisis, characterized by a rise in subprime mortgage delinquencies and foreclosures, and the resulting decline of securities backed by said mortgages....

in September 2007, the Federal Reserve began cutting the federal funds rate. The Fed cut rates by 0.25% after its December 11, 2007 meeting and disappointed many individual investors who expected a higher rate cut: the Dow Jones Industrial Average dropped by nearly 300 points at its close that day. The Fed slashed the rate 0.75% in an emergency action on January 22, 2008 to assist in reversing a significant market slide influenced by weakening international markets. The Dow Jones Industrial Average initially fell nearly 4% (465 points) at the start of trading and then rebounded to a more tolerable 1.06% (128 point) loss. On January 30, 2008, eight days after the 75 points decrease, the Fed lowered its rate again, this time by 50 points.

Key laws affecting the Federal Reserve

Key laws affecting the Federal Reserve have been:- Banking Act of 1935

- Employment Act of 1946

- Federal Reserve-Treasury Department Accord of 19511951 AccordThe 1951 Accord, also known simply as the Accord, was an agreement between the U.S. Department of the Treasury and the Federal Reserve that restored independence to the Fed....

- Bank Holding Company Act of 1956Bank Holding Company Act of 1956The Bank Holding Company Act of 1956 is a United States Act of Congress that regulates the actions of bank holding companies.The original law , specified that the Federal Reserve Board of Governors must approve the establishment of a bank holding company, and prohibited bank holding companies...

and the amendments of 1970 - Federal Reserve Reform Act of 1977

- International Banking Act of 1978

- Full Employment and Balanced Growth Act (1978)

- Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control ActDepository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control ActThe Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act, a United States federal financial statute law passed in 1980, gave the Federal Reserve greater control over non-member banks.* It forced all banks to abide by the Fed's rules....

(1980) - Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery and Enforcement Act of 1989Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery and Enforcement Act of 1989The Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery, and Enforcement Act of 1989 , , is a United States federal law enacted in the wake of the savings and loan crisis of the 1980s....

- Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Improvement Act of 1991Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Improvement Act of 1991The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Improvement Act of 1991 , passed during the Savings and loan crisis, strengthened the power of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation....

- Gramm-Leach-Bliley ActGramm-Leach-Bliley ActThe Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act , also known as the Financial Services Modernization Act of 1999, is an act of the 106th United States Congress...

(1999)