Hugh MacDiarmid

Encyclopedia

Hugh MacDiarmid is the pen name of Christopher Murray Grieve (11 August 1892, Langholm

– 9 September 1978, Edinburgh

), a significant Scottish poet of the 20th century. He was instrumental in creating a Scottish version of modernism

and was a leading light in the Scottish Renaissance

of the 20th century. Unusually for a first generation modernist, he was a communist; unusually for a communist, however, he was a committed Scottish nationalist. He wrote both in English and in literary Scots

(often referred to as Lallans

).

during the First World War

. After the war, he married and returned to journalism. His first book, Annals of the Five Senses (1923) was a mixture of prose and poetry in English, but he then turned to Scots for a series of books, culminating in what is probably his best known work, the book-length A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle

. This poem is widely regarded as one of the most important long poems in 20th century Scottish literature

. After that, he published several books containing poems in both English and Scots.

. He was also a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain

. During the 1930s, he was expelled from the former for being a communist and from the latter for being a nationalist. In 1949, George Orwell

compiled a list of suspected communist sympathisers for British intelligence. He included MacDiarmid in this list. In 1956, MacDiarmid rejoined the Communist Party.

As Grieve, he stood in the 1950 election

in the Glasgow Kelvingrove

constituency, as the Scottish National Party

candidate, coming last with 639 votes. He also stood against Alec Douglas-Home

in Kinross and Western Perthshire

for the Communist Party at the 1964 election, taking only 127 votes. MacDiarmid listed Anglophobia

amongst his hobbies in his Who's Who

entry.

In 2010, letters were discovered showing that he believed a Nazi invasion of Britain would benefit Scotland. In a letter sent from Whalsay, Shetland, in April 1941, he wrote: “On balance I regard the Axis powers, tho’ more violently evil for the time being, less dangerous than our own government in the long run and indistinguishable in purpose." A year earlier, in June 1940, he wrote: “Although the Germans are appalling enough, they cannot win, but the British and French bourgeoisie can and they are a far greater enemy. If the Germans win they could not hold their gain for long, but if the French and British win it will be infinitely more difficult to get rid of them.” Marc Horne in the Daily Telegraph commented: "MacDiarmid flirted with fascism in his early thirties, when he believed it was a doctrine of the left. In two articles written in 1923, Plea for a Scottish Fascism and Programme for a Scottish Fascism, he appeared to support Mussolini’s regime. By the 1930s however, following Mussolini’s lurch to the right, his position had changed and he castigated Neville Chamberlain over his appeasement of Hitler’s expansionism." Deirdre Grieve, MacDiarmid’s daughter-in-law and literary executor, noted: “I think he entertained almost every ideal it was possible to entertain at one point or another." The Sunday Times 4 April 2010 "Hugh MacDiarmid: I’d prefer Nazi rule"

As his interest in science and linguistics increased, MacDiarmid found himself turning more and more to English as a means of expression so that most of his later poetry is written in that language. His ambition was to live up to Rilke's dictum that 'the poet must know everything' and to write a poetry that contained all knowledge. As a result, many of the poems in Stony Limits (1934) and later volumes are a kind of found poetry

As his interest in science and linguistics increased, MacDiarmid found himself turning more and more to English as a means of expression so that most of his later poetry is written in that language. His ambition was to live up to Rilke's dictum that 'the poet must know everything' and to write a poetry that contained all knowledge. As a result, many of the poems in Stony Limits (1934) and later volumes are a kind of found poetry

reusing text from a range of sources. Just as he had used Jameson's dialect dictionary for his poems in 'synthetic Scots', so he used Chambers Twentieth Century Dictionary for poems such as 'On a Raised Beach'. Other poems, including 'On a Raised Beach' and 'Etika Preobrazhennavo Erosa' used extensive passages of prose. This practice, particularly in the poem 'Perfect', led to accusations of plagiarism

from supporters of the Welsh poet Glyn Jones, to which MacDiarmid's response was 'The greater the plagiarism the greater the work of art.' The great achievement of this late poetry is to attempt on an epic

scale to capture the idea of a world without God in which all the facts the poetry deals with are scientifically verifiable. In his critical work Lives of the Poets, Michael Schmidt notes that Hugh MacDiarmid 'had redrawn the map of Scottish poetry and affected the whole configuration of English literature'.

MacDiarmid wrote a number of non-fiction prose works, including Scottish Eccentrics and his autobiography Lucky Poet. He also did a number of translations from Scottish Gaelic, including Duncan Ban MacIntyre

's Praise of Ben Dorain, which were well received by native speakers including Sorley MacLean

.

in Dumfries and Galloway. The town is home to a monument in his honour made of cast iron which takes the form of a large open book depicting images from his writings.

MacDiarmid lived in Montrose

for a time where he worked for the local newspaper the Montrose Review

.

MacDiarmid also lived on the isle of Whalsay

in Shetland, in Sodom

(Sudheim)

Hugh MacDiarmid is commemorated in Makars' Court

, outside The Writers' Museum, Lawnmarket, Edinburgh.

Selections for Makars' Court are made by The Writers' Museum, The Saltire Society and The Scottish Poetry Library.

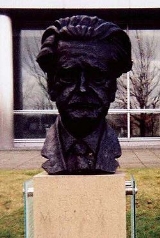

and a bronze was acquired by the National Portrait Gallery. The terracotta original is held in the collection of the artist The correspondence file relating to the MacDiarmid bust is held in the archive of the Henry Moore Foundation

's Henry Moore Institute in Leeds

.

Langholm

Langholm , also known colloquially as the "Muckle Toon", is a burgh in Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland, on the River Esk and the A7 road.- History:...

– 9 September 1978, Edinburgh

Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland, the second largest city in Scotland, and the eighth most populous in the United Kingdom. The City of Edinburgh Council governs one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas. The council area includes urban Edinburgh and a rural area...

), a significant Scottish poet of the 20th century. He was instrumental in creating a Scottish version of modernism

Modernism

Modernism, in its broadest definition, is modern thought, character, or practice. More specifically, the term describes the modernist movement, its set of cultural tendencies and array of associated cultural movements, originally arising from wide-scale and far-reaching changes to Western society...

and was a leading light in the Scottish Renaissance

Scottish Renaissance

The Scottish Renaissance was a mainly literary movement of the early to mid 20th century that can be seen as the Scottish version of modernism. It is sometimes referred to as the Scottish literary renaissance, although its influence went beyond literature into music, visual arts, and politics...

of the 20th century. Unusually for a first generation modernist, he was a communist; unusually for a communist, however, he was a committed Scottish nationalist. He wrote both in English and in literary Scots

Scots language

Scots is the Germanic language variety spoken in Lowland Scotland and parts of Ulster . It is sometimes called Lowland Scots to distinguish it from Scottish Gaelic, the Celtic language variety spoken in most of the western Highlands and in the Hebrides.Since there are no universally accepted...

(often referred to as Lallans

Lallans

Lallans , a variant of the Modern Scots word lawlands meaning the lowlands of Scotland, was also traditionally used to refer to the Scots language as a whole...

).

Early life and writings

After leaving school in 1910, MacDiarmid worked as a journalist for five years. He then served in the Royal Army Medical CorpsRoyal Army Medical Corps

The Royal Army Medical Corps is a specialist corps in the British Army which provides medical services to all British Army personnel and their families in war and in peace...

during the First World War

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

. After the war, he married and returned to journalism. His first book, Annals of the Five Senses (1923) was a mixture of prose and poetry in English, but he then turned to Scots for a series of books, culminating in what is probably his best known work, the book-length A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle

A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle

A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle is a long poem by Hugh MacDiarmid written in Scots and published in 1926. It is composed as a form of monologue with influences from stream of consciousness genres of writing...

. This poem is widely regarded as one of the most important long poems in 20th century Scottish literature

Scottish literature

Scottish literature is literature written in Scotland or by Scottish writers. It includes literature written in English, Scottish Gaelic, Scots, Brythonic, French, Latin and any other language in which a piece of literature was ever written within the boundaries of modern Scotland.The earliest...

. After that, he published several books containing poems in both English and Scots.

Politics

In 1928, MacDiarmid helped found the National Party of ScotlandNational Party of Scotland

The National Party of Scotland was a political party in Scotland and a forerunner of the current Scottish National Party.The NPS was formed in 1928 after John MacCormick of the Glasgow University Scottish Nationalist Association called a meeting of all those favouring the establishment of a party...

. He was also a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain

Communist Party of Great Britain

The Communist Party of Great Britain was the largest communist party in Great Britain, although it never became a mass party like those in France and Italy. It existed from 1920 to 1991.-Formation:...

. During the 1930s, he was expelled from the former for being a communist and from the latter for being a nationalist. In 1949, George Orwell

George Orwell

Eric Arthur Blair , better known by his pen name George Orwell, was an English author and journalist...

compiled a list of suspected communist sympathisers for British intelligence. He included MacDiarmid in this list. In 1956, MacDiarmid rejoined the Communist Party.

As Grieve, he stood in the 1950 election

United Kingdom general election, 1950

The 1950 United Kingdom general election was the first general election ever after a full term of a Labour government. Despite polling over one and a half million votes more than the Conservatives, the election, held on 23 February 1950 resulted in Labour receiving a slim majority of just five...

in the Glasgow Kelvingrove

Glasgow Kelvingrove (UK Parliament constituency)

Glasgow Kelvingrove was a burgh constituency represented in the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom from 1918 until 1983. It elected one Member of Parliament using the first-past-the-post voting system.- Boundaries :...

constituency, as the Scottish National Party

Scottish National Party

The Scottish National Party is a social-democratic political party in Scotland which campaigns for Scottish independence from the United Kingdom....

candidate, coming last with 639 votes. He also stood against Alec Douglas-Home

Alec Douglas-Home

Alexander Frederick Douglas-Home, Baron Home of the Hirsel, KT, PC , known as The Earl of Home from 1951 to 1963 and as Sir Alec Douglas-Home from 1963 to 1974, was a British Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from October 1963 to October 1964.He is the last...

in Kinross and Western Perthshire

Kinross and Western Perthshire (UK Parliament constituency)

Kinross and Western Perthshire was a county constituency of the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom from 1918 until 1983, representing, at any one time, a seat for one Member of Parliament , elected by the first past the post system of election.-Boundaries:The constituency was...

for the Communist Party at the 1964 election, taking only 127 votes. MacDiarmid listed Anglophobia

Anglophobia

Anglophobia means hatred or fear of England or the English people. The term is sometimes used more loosely for general Anti-British sentiment...

amongst his hobbies in his Who's Who

Who's Who (UK)

Who's Who is an annual British publication of biographies which vary in length of about 30,000 living notable Britons.-History:...

entry.

In 2010, letters were discovered showing that he believed a Nazi invasion of Britain would benefit Scotland. In a letter sent from Whalsay, Shetland, in April 1941, he wrote: “On balance I regard the Axis powers, tho’ more violently evil for the time being, less dangerous than our own government in the long run and indistinguishable in purpose." A year earlier, in June 1940, he wrote: “Although the Germans are appalling enough, they cannot win, but the British and French bourgeoisie can and they are a far greater enemy. If the Germans win they could not hold their gain for long, but if the French and British win it will be infinitely more difficult to get rid of them.” Marc Horne in the Daily Telegraph commented: "MacDiarmid flirted with fascism in his early thirties, when he believed it was a doctrine of the left. In two articles written in 1923, Plea for a Scottish Fascism and Programme for a Scottish Fascism, he appeared to support Mussolini’s regime. By the 1930s however, following Mussolini’s lurch to the right, his position had changed and he castigated Neville Chamberlain over his appeasement of Hitler’s expansionism." Deirdre Grieve, MacDiarmid’s daughter-in-law and literary executor, noted: “I think he entertained almost every ideal it was possible to entertain at one point or another." The Sunday Times 4 April 2010 "Hugh MacDiarmid: I’d prefer Nazi rule"

Later writings

Found poetry

Found poetry is a type of poetry created by taking words, phrases, and sometimes whole passages from other sources and reframing them as poetry by making changes in spacing and/or lines , or by altering the text by additions and/or deletions...

reusing text from a range of sources. Just as he had used Jameson's dialect dictionary for his poems in 'synthetic Scots', so he used Chambers Twentieth Century Dictionary for poems such as 'On a Raised Beach'. Other poems, including 'On a Raised Beach' and 'Etika Preobrazhennavo Erosa' used extensive passages of prose. This practice, particularly in the poem 'Perfect', led to accusations of plagiarism

Plagiarism

Plagiarism is defined in dictionaries as the "wrongful appropriation," "close imitation," or "purloining and publication" of another author's "language, thoughts, ideas, or expressions," and the representation of them as one's own original work, but the notion remains problematic with nebulous...

from supporters of the Welsh poet Glyn Jones, to which MacDiarmid's response was 'The greater the plagiarism the greater the work of art.' The great achievement of this late poetry is to attempt on an epic

Epic poetry

An epic is a lengthy narrative poem, ordinarily concerning a serious subject containing details of heroic deeds and events significant to a culture or nation. Oral poetry may qualify as an epic, and Albert Lord and Milman Parry have argued that classical epics were fundamentally an oral poetic form...

scale to capture the idea of a world without God in which all the facts the poetry deals with are scientifically verifiable. In his critical work Lives of the Poets, Michael Schmidt notes that Hugh MacDiarmid 'had redrawn the map of Scottish poetry and affected the whole configuration of English literature'.

MacDiarmid wrote a number of non-fiction prose works, including Scottish Eccentrics and his autobiography Lucky Poet. He also did a number of translations from Scottish Gaelic, including Duncan Ban MacIntyre

Duncan Bàn MacIntyre

Donnchadh Bàn Mac an t-Saoir is one of the most renowned of Scottish Gaelic poets and formed an integral part of one of the golden ages of Gaelic poetry in Scotland during the 18th century...

's Praise of Ben Dorain, which were well received by native speakers including Sorley MacLean

Sorley MacLean

Sorley MacLean was one of the most significant Scottish poets of the 20th century.-Early life:He was born at Osgaig on the island of Raasay on 26 October 1911, where Scottish Gaelic was the first language. He attended the University of Edinburgh and was an avid shinty player playing for the...

.

Places of interest

MacDiarmid grew up in the Scottish town of LangholmLangholm

Langholm , also known colloquially as the "Muckle Toon", is a burgh in Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland, on the River Esk and the A7 road.- History:...

in Dumfries and Galloway. The town is home to a monument in his honour made of cast iron which takes the form of a large open book depicting images from his writings.

MacDiarmid lived in Montrose

Montrose, Angus

Montrose is a coastal resort town and former royal burgh in Angus, Scotland. It is situated 38 miles north of Dundee between the mouths of the North and South Esk rivers...

for a time where he worked for the local newspaper the Montrose Review

Montrose Review

The Montrose Review was established on 11 January 1811, with the full title of The Montrose, Arbroath and Brechin Review, and Forfar and Kincardine Shires Advertiser...

.

MacDiarmid also lived on the isle of Whalsay

Whalsay

-Geography:Whalsay, also known as "The Bonnie Isle", is a peat-covered island in the Shetland Islands. It is situated east of the Shetland Mainland and has an area of . The main settlement is Symbister, where the fishing fleet is based. The fleet is composed of both pelagic and demersal vessels...

in Shetland, in Sodom

Sodom, Shetland

Sodom is a settlement on Whalsay, Shetland. The name is a corruption of the Old Norse Suðheim meaning "south home". It was formerly the home of Hugh MacDiarmid, who was greatly amused at the anglicised form of the name....

(Sudheim)

Hugh MacDiarmid is commemorated in Makars' Court

Makars' Court

The Makars' Court is the paved area next to the Scottish Writers' Museum in Lady Stair's Close in Edinburgh, Scotland. The stone slabs of the court are inscribed with the names of Makars...

, outside The Writers' Museum, Lawnmarket, Edinburgh.

Selections for Makars' Court are made by The Writers' Museum, The Saltire Society and The Scottish Poetry Library.

Portrait in National Portrait Gallery primary collection

Hugh MacDiarmid sat for sculptor Alan ThornhillAlan Thornhill

Alan Thornhill is a British artist and sculptor whose long association with clay developed from pottery into sculpture. His evolved methods of working enabled the dispensing of the sculptural armature to allow improvisation, whilst his portraiture challenges notions of normality through rigorous...

and a bronze was acquired by the National Portrait Gallery. The terracotta original is held in the collection of the artist The correspondence file relating to the MacDiarmid bust is held in the archive of the Henry Moore Foundation

Henry Moore Foundation

The Henry Moore Foundation is a registered charity in England, established for education and promotion of the fine arts — in particular, to advance understanding of the works of Henry Moore. The charity was set up with a gift from the artist in 1977...

's Henry Moore Institute in Leeds

Leeds

Leeds is a city and metropolitan borough in West Yorkshire, England. In 2001 Leeds' main urban subdivision had a population of 443,247, while the entire city has a population of 798,800 , making it the 30th-most populous city in the European Union.Leeds is the cultural, financial and commercial...

.

Further reading

- Duncan Glen (1964) Hugh Macdiarmid (Christopher Murray Grieve) and the Scottish Renaissance , Chambers, Edinburgh et al.

- Michael Grieve and Alexander Scott (1972) The Hugh Macdiarmid Anthology: Poems in Scots and English, Routledge and Kegan Paul, London

- Gordon Wright (1977) MacDiarmid: An Illustrated Biography, Gordon Wright Publishing

- Alan BoldAlan BoldAlan Norman Bold was a Scottish poet, biographer and journalist.He edited Hugh MacDiarmid's Letters and wrote the influential biography MacDiarmid. Bold had acquainted himself with MacDiarmid in 1963 while still an English Literature student at Edinburgh University. His debut work, Society...

(1983) MacDiarmid: The Terrible Crystal, Routledge & Kegan Paul - Alan Bold (1984) Letters, Hamish Hamilton

- Alan Bold (1988) MacDiarmid A Critical Biography, John Murray

- John Baglow (1987) Hugh MacDiarmid: The Poetry of Self (criticism), McGill-Queen’s Press

- Scott Lyall and Margery Palmer McCulloch (eds) (2011) The Edinburgh Companion to Hugh MacDiarmid, Edinburgh University Press

- Scott Lyall (2006) Hugh MacDiarmid's Poetry and Politics of Place: Imagining a Scottish Republic, Edinburgh University Press

- Beth Junor (2007) Scarcely Ever Out of My Thoughts: The Letters of Valda Trevlyn Grieve to Christopher Murray Grieve (Hugh MacDiarmid) Word Power

- Alan Riach (1991) Hugh MacDiarmid’s Epic Poetry, Edinburgh University Press

- An Anthology from XX (magazine)X, A Quarterly Review was a British arts review published in London which ran for seven issues between 1959-1962. It was founded and co-edited by Patrick Swift and David Wright...

(Oxford University Press 1988). X (magazine)X (magazine)X, A Quarterly Review was a British arts review published in London which ran for seven issues between 1959-1962. It was founded and co-edited by Patrick Swift and David Wright...

ran from 1959-62. Edited by the poet David WrightDavid Wright (poet)David John Murray Wright was an author and "an acclaimed South African-born poet".-Biography:Wright was born in Johannesburg, South Africa 23 February 1920 of normal hearing....

& the painter Patrick SwiftPatrick SwiftPatrick Swift was an artist born in Dublin, Ireland. Patrick Swift was a painter and key cultural figure in Dublin and London before moving to the Algarve in southern Portugal, where he is buried in the town of Porches...

. Contributors included MacDiarmid, Robert GravesRobert GravesRobert von Ranke Graves 24 July 1895 – 7 December 1985 was an English poet, translator and novelist. During his long life he produced more than 140 works...

, W.H. Auden, Samuel BeckettSamuel BeckettSamuel Barclay Beckett was an Irish avant-garde novelist, playwright, theatre director, and poet. He wrote both in English and French. His work offers a bleak, tragicomic outlook on human nature, often coupled with black comedy and gallows humour.Beckett is widely regarded as among the most...

, et al.